2015 Volume 65 Issue 1 Pages 77-84

2015 Volume 65 Issue 1 Pages 77-84

The combined total annual yield of six major crops (maize, rice, wheat, cassava, soybean, and potato; Solanum tuberosum L.) amounts to 3.1 billion tons. In recent years, staple crops have begun to be used as substitutes for fossil fuel and feedstocks. The diversion of crop products to fuels and industrial feedstocks has become a concern in many countries because of competition for arable lands and increased food prices. These concerns are definitely justified; however, if plant biotechnology succeeds in increasing crop yields to double the current yields, it will be possible to divert the surplus to purposes other than food without detrimental effects. Maize, rice, wheat, and soybean bear their sink organs in the aerial parts of the plant, and potato in the underground parts. Plants with aerial storage organs cannot accumulate products beyond their capacity to support the weight of these organs. In contrast, potato has heavy storage organs that are supported by the soil. In this mini-review, we introduce strategies of intensifying potato productivity and discuss recent advances in this research area.

Farmers, researchers, and crop breeders have put a lot of effort into increasing crop yields through screening crop varieties to obtain those with mandatory prerequisites as crops, including sufficient amounts of nutrients. The major crop products are polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids. These compounds store solar energy in carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen bonds; the amount of stored energy ranges from 3.8 kcal/g in polysaccharides to 13.5 kcal/g in alkanes. Such plant products are not only energy reservoirs, but also resources to supply the building blocks for living organisms.

Starch produced by crop plants has attracted intense attention from the public and industries. Starch is easily degraded into glucose, which is an important energy source for humans, and can be easily converted into various feedstocks (Bahaji et al. 2014). When crop plants are considered as both an energy source and food, their importance should be ranked according to their relative potential in storing solar energy in stable biological compounds per fixed land area. One such ideal crop may be the potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). In the Netherlands, the annual yield of potato is 45 tons/ha (FAOSTAT 2012), corresponding to 7.9 tons polysaccharide/ha. In general, plants with heavier sink organs in the aerial part must invest a large proportion of carbon and energy into making the plant body strong enough to bear the sink organs. This is the case in high-yielding rice varieties and mutants (Ashikari et al. 2005).

The performance of a living organism is governed by the whole set of genes in its genome. The organism performs best when all of the genes function in the optimum combination. However, most organisms are exposed to various environmental stresses during their lifetime. Boyer (1982) estimated that crops achieve only 20–30% of their potential productivity on local farms in the U.S.A. (Fig. 1). Biotic stresses can be minimized by the appropriate use of pesticides and herbicides; however, abiotic stresses can be dominant in farming. Alleviation of these abiotic stresses may improve crop productivity. The molecular responses of crop plants to various environmental stresses and the molecular alleviation of these stresses at the molecular level are discussed in another review (Kikuchi et al. 2015).

Research strategy of this laboratory. Maximum productivity of a crop plant results from correct functioning of all genes in its genome under ideal growth conditions. Boyer (1982) reported that many crops produce yields 70–80% lower than those under ideal conditions. See text for details.

The potential productivity of crop plants is defined by the set of genes in their genomes. However, many enzymes and proteins have been identified as rate-limiting entities in photosynthesis, translocation of photosynthates, and carbon storage (Fig. 1) (Yokota and Shigeoka 2008). Living organisms inherit the whole set of genes from their ancestors, irrespective of their performance. This is due to reproductive isolation of species from different phylogenetic lineages. Genetic transformation of crops with more suitable genes has improved the field performance of many crops in the last 20 years. In this mini-review, we discuss recent advances in the improvement of potato yields, focusing on molecular approaches. This review does not deal with long-distance signal transduction from shoots to tubers or hormonal regulation in potatoes. These areas have been covered in other recent reviews (Abelenda et al. 2014, Corbesier et al. 2007, Gonzalez-Schain et al. 2012, Hannapel 2013, Martinez-Garcia et al. 2002, Mason 2013, Navarro et al. 2011, Pasare et al. 2013, Roumeliotis et al. 2012, Sarkar 2008, Suárez-López 2013).

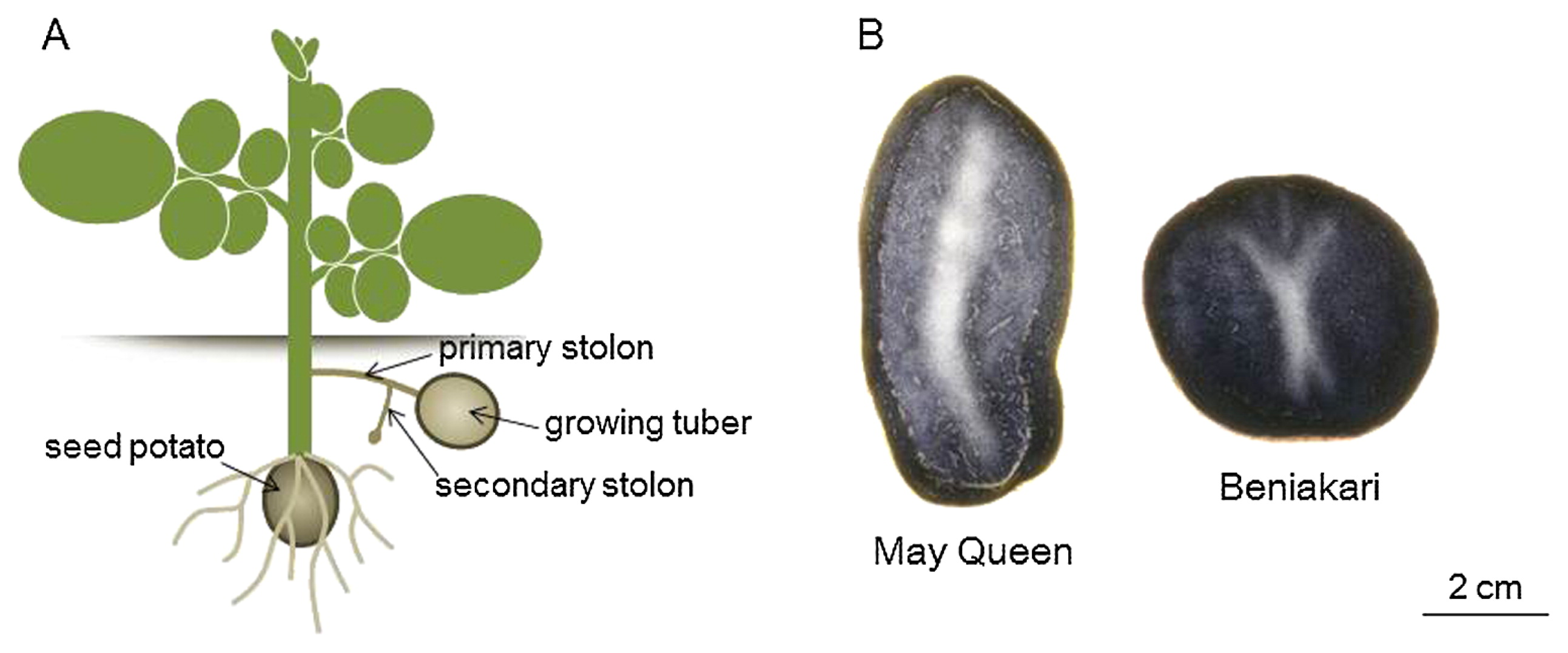

The sink organs of potato are the underground tubers, and the source organs are its leaves (Fig. 2A). Photosynthesis begins with the synthesis of sucrose from fixed CO2 in leaf mesophyll cells. Sucrose synthesized in the cytosol of mesophyll cells is transported to companion cells located next to the mesophyll cells. The mesophyll cells in the source leaves supply sucrose via symplastic transport to other mesophyll cells through plasmodesmata (Fig. 3). Sucrose is concentrated against a steep upward gradient of the solute between the mesophyll cells and companion cells by an energy-requiring sucrose transporter. The companion cells symplastically transport sucrose to the sieve elements. Sucrose flows through the sieve elements in the source leaves to sink organs via an osmotically generated hydrostatic pressure difference between the source and sink (Lalonde et al. 2003). The photosynthates transferred to sink organs, including tubers and developing organs, are then unloaded for storage and/or used to build new cellular components. In the tuber development process, axillary buds on the main stem covered by soil develop into the primary subterranean stem or primary stolon. The axillary sprouts on the primary stolon sometimes generate secondary stolons. Tubers develop from the apex and axillary buds on the primary and additional stolons (Fig. 2A). Starch mainly accumulates in the cortex, phloem parenchyma, and external pith layers in potato tubers (Fig. 2B).

Morphology of whole potato plant (A) and iodine-stained longitudinal section of potato tubers (B). See text for details for A. In B, tubers were cut into 1-mm-thick slices, which were stained with diluted iodine solution (10 mM) for 1 min. Slices were washed in water to reveal differential staining of starch accumulation.

Proposed mechanism of phloem loading in potato source leaves (Rennie and Turgeon 2009). Interlinked hexagon and heptagon represent sucrose molecule. Cylinder on cell boundary of companion cell represents sucrose transporter. See text for other details.

In the source leaves, photosynthesis in chloroplasts converts light energy into chemical energy, which is then used for the chemical reduction of CO2 fixed by ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO). The conversion of light energy into chemical energy, the “light reaction”, occurs in thylakoid membranes. A set of reactions leading from CO2 to sugars, known as the “dark reaction”, occur in the chloroplast stroma. At saturating light intensity, photosynthesis is limited by the activity of RuBisCO until photosynthesis almost reaches saturation with respect to the CO2 concentration, and is limited by the inorganic phosphate (Pi) regeneration rate at much higher CO2 concentrations (Sage and Coleman 2001). There is a ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP)-limiting phase between these RuBisCO-limiting and Pi-limiting phases. Potato photosynthesis is limited by the light reaction below 700 μmol photons/m2/s (Laisk et al. 2007), and by the dark reaction at higher light intensities. Considering the CO2 concentration in the intercellular space (Ci)-response curve of potato photosynthesis, CO2 fixation by RuBisCO limits photosynthesis below a Ci range of 500 to 600 μbar (Ku et al. 1977). Above this range, photosynthesis is limited by the regeneration of RuBP and then regeneration of Pi.

These limiting steps vary depending on the light intensity and CO2 concentration. Photosynthesis is saturated at a higher light intensity under saturating CO2 concentrations, but at a lower light intensity under lower CO2 concentrations (Ögren 1993, Ögren and Evans 1993). Sedoheptulose 1,7-bisphophatase (SBPase) is a severely rate-limiting enzyme in the CO2-fixation cycle in tobacco (Harrison et al. 1998). Overexpression of the cyanobacterial gene encoding an enzyme with dual activity (both fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase and sedoheptulose bisphosphatase (FBP/SBPase) activities) in tobacco chloroplasts increased the chloroplast RuBP concentration by 30–50%, compared with that in the control (Fig. 4) (Miyagawa et al. 2001, Tamoi et al. 2006, Yabuta et al. 2008). Higher concentrations of RuBP were required to activate RuBisCO activase (Portis et al. 1986) and for RuBP to bind to the activity-regulatory sites to increase RuBisCO activity by 30–40%, compared with that of non-RuBP-bound RuBisCO (Yokota 1991, Yokota et al. 1994).

Photosynthetic CO2 fixation and biomass production after introducing cyanobacterial FBP/SBPase gene into chloroplast genome of tobacco. In inset, blue line shows relationship between photosynthetic CO2 fixation rate and light intensity in wild-type tobacco; red line represents transformant data. A and B show pictures of wild-type and transgenic tobacco.

Sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) is another candidate for intensifying source activity, because the potato accumulates starch in leaf chloroplasts during the daytime (Ishimaru et al. 2008). Transgenic potato expressing the maize SPS gene under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter showed two-fold higher SPS activity than that in wild-type potato. Also, leaf senescence was delayed in the transformant. The tuber weight and total yield of the transformant were approximately 20% greater than those of the wild type, partly because of increased transport of sucrose from the leaves to tubers, and partly because of delayed senescence.

Glycolate, the product of the oxygenase reaction of RuBisCO, is metabolized to phosphoglycerate via the glycolate pathway in plants (Tolbert 1981). This organic acid is a carbon source for Escherichia coli. In this bacterium, glycolate is oxidized to glyoxylate by membranous glycolate dehydrogenase (Lord 1972, Sallal and Nimer 1989) and then to phosphoglycerate via tartronic semialdehyde and glycerate (Hansen and Hayashi 1962). When E. coli genes encoding glycolate dehydrogenase, glyoxylate carboligase, and tartronic semialdehyde reductase were introduced into Arabidopsis chloroplasts, the photosynthetically produced glycolate was not metabolized in the glycolate pathway, but was metabolized in the glycerate-synthesizing pathway via tartronic semialdehyde in chloroplasts (Kebeish et al. 2007). In that reaction, one CO2 molecule is produced in the glyoxylate carboligase reaction to form tartronic semialdehyde. In that study, the CO2 fixation rate was approximately 50% higher in the transformant than that in the wild type, and there was much weaker O2 inhibition of CO2 fixation in the transformant than that in the wild type. The released CO2 in chloroplasts was fixed in the stroma by RuBisCO.

Similar results have been obtained using transformants expressing only glycolate dehydrogenase, although the effect of the genetic manipulation in that case was much weaker (Nölke et al. 2014). Glycolate dehydrogenase is a membrane-associated enzyme complex in algae and E. coli. The Euglena enzyme is coupled to the mitochondrial respiratory chain to produce ATP (Yokota et al. 1978). In Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and E. coli, these proteins show meaningful homology (Nakamura et al. 2005). It seems that, in the chloroplast membranes, the E. coli glycolate dehydrogenase is coupled to a plastid terminal oxidase involved in chlororespiration (Yu et al. 2014).

Maier et al. (2012) proposed another idea to reduce photorespiration in Arabidopsis. Their system made use of glycolate oxidase, malate synthase, and catalase in chloroplasts. Glycolate is oxidized by glycolate oxidase to glyoxylate and H2O2, two molecules of which are decomposed to H2O and O2 by catalase. Malate synthase conjugates glyoxylate and acetyl-CoA produced from pyruvate by pyruvate dehydrogenase in the stroma. Malate is converted into pyruvate and CO2 by NAPD-malic enzyme, and NADPH is formed concomitantly. Pyruvate is oxidized to acetyl-CoA and CO2 with the production of NADH. Two molecules of glycolate can be converted to four molecules of CO2 in this pathway. The CO2 liberated in this newly introduced pathway may improve photosynthetic performance to some extent.

The maintenance of suitable levels of inorganic phosphate (Pi) in chloroplasts is essential for photosynthesis. A Pi-transporter in the envelope of chloroplasts exchanges triose phosphate and Pi across the envelope. Expression of the anti-sense RNA sequence of the tobacco Pi-transporter and overexpression of the Flaveria transporter gene did not affect photosynthesis of tobacco (Häusler et al. 2000). In contrast, overexpression of Arabidopsis purple acid phosphatase in potato decreased the soluble sugar content in the leaf and increased starch and soluble sugar contents in the tubers (Zhang et al. 2014). This overexpression induced the expression of the sucrose transporter gene StSUT1. However, the exact function of this gene remains unclear.

The SUT genes involved in uploading sucrose from source leaves to the phloem and unloading in the tubers have been identified (Kühn et al. 2003). However, expressing the spinach SUT1 gene under the control of the CaMV35S promoter in potato did not increase tuber yield (Leggewie et al. 2003). Transgenic potato expressing rice SUT5Z (but not SUT2M) under the control of the patatin promoter produced twice as many tubers as did the control (Sun et al. 2011).

Upregulation of starch synthesis in potato tubers is an effective strategy to increase sink activity. In this way, more carbon from the photosynthetic product, sucrose, is stored in the tubers. During the transition to the tuber-swelling stage from the stolon-elongation stage, there is a switch in sucrose metabolism in the stolon subapical region (Fernie and Willmitzer 2001). ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase), which catalyzes the production of ADP-glucose, the precursor of starch synthesis, is a rate-limiting, highly regulatory enzyme in starch synthesis. The detailed regulatory mechanisms of sucrose-to-starch conversion have been reviewed by Geigenberger (2003) and Herbers and Sonnewald (1998). Regierer et al. (2002) modulated the ATP/ADP ratio in amyloplasts by changing the activity of plastidial adenylate kinase, and succeeded in increasing tuber yield by more than 80%. An increase in the ATP level may activate AGPase, and consequently, increase ADP-glucose levels. Jonik et al. (2012) overexpressed two tuber plastidic metabolite translocators, glucose 6-phosphate/phosphate (G6P) translocator (GPT) and adenylate translocator (AdT), in potato. GPT and AdT modulate amyloplast G6P and ATP levels, respectively. An increase in the concentration of G6P, the precursor of starch, increased AGPase activity. Baroja-Fernández et al. (2009) overexpressed sucrose synthase in potato plants, and found that the transformants showed increased accumulation of UDP-glucose, ADP-glucose, and starch.

Shoot branching (tillering) is an important trait determining rice grain yield (Liang et al. 2014, Seto et al. 2012). Strigolactones (SLs) have been identified as an endogenous plant hormone that regulates aboveground plant architecture (Umehara et al. 2008). It has been proposed that SLs and cytokinins (CKs) have competitive functions in tillering in rice (Minakuchi et al. 2010); SLs and CKs also participate in shoot branching in potato, a dicot (Müller and Leyser 2011). Stolons are induced from subterranean axillary buds, and the number of stolons is strongly correlated with the number of tubers (Fig. 2). Accordingly, SLs and CKs may be involved in determining potato yield. Isopentenyltransferase (IPT) transfers the isopentenyl moiety of dimethylallyl pyrophosphate to ATP, ADP, or AMP in the first step of CK synthesis (Kamada-Nobusada and Sakakibara 2009). Application of exogenous CK to potato stolons was shown to induce tuberization (Mauk and Langille 1978). In potato, SLs were shown to inhibit growth of axillary stolon buds, as well as the aerial parts of the plant (Roumeliotis et al. 2012). Genetic manipulation of the CK synthesis pathways may be a promising strategy to increase the productivity of potatoes in the near future. Cytokinin-synthesizing enzymes include IPT, CYP735A (an enzyme that converts isopentenyl nucleotides to trans-zeatin nucleotides), and a nucleosidase that liberates isopentenyl adenine and trans-zeatin. Ectopic overexpression of a gene encoding the nucleosidase (LOG1) in tomato plants, a Solanum species, resulted in the formation of aerial microtubers from juvenile buds (Eviatar-Ribak et al. 2013).

The RAN-GTPase (RAN) belongs to the small G-protein family and participates in diverse cellular events, such as a nucleocytoplasmic cargo trafficking, mitotic spindle assembly, and nuclear pore and envelope formation. This protein has been functionally and structurally characterized (Ciciarello et al. 2007, Dasso 2002, Sato and Toda 2010, Vernoud et al. 2003). The present consensus is that, in yeast and animal cells, this protein is involved in driving cell cycle events. However, RAN has been not been extensively studied in plants. Wild watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.) is a xerophyte originating from the semidry Kalahari Desert in southern Africa (Yokota et al. 2002). We found that wild watermelon roots developed much more rapidly under drought conditions than under well-watered conditions (Fig. 5). A proteome analysis of the roots sensing drying soil revealed that RanGTPase1 (RAN1) was induced under these conditions (Yoshimura et al. 2008). The watermelon RAN1 gene (CLRAN1) is expressed at a relatively early phase of the stress response, whereas the other RAN-related gene, CLRAN2, is expressed at much later phase in root tissues. In transgenic Arabidopsis, root development was affected by the level of heterologous expression of CLRAN1 under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Interestingly, RAN1 and RAN-binding protein are expressed in potato in the early phase of stolon development (Lehesranta et al. 2006, Sarkar 2008). In our preliminary experiments, overexpression of RAN1 under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter caused potato plants to form more tubers (Fig. 6) (Kasajima et al. unpublished).

Root growth of watermelon plants with or without watering. Wild and domesticated watermelon plants (10 plants each) grown under moderate light intensity (250 μmol photons m−2 s−1) for 1 week were subjected to drought stress by withholding watering. Root biomass of seedlings (dry weight) was measured on days 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 after cessation of watering. Open circles, well-watered wild watermelon; filled circles, drought-stressed wild watermelon; open diamonds, well-watered domestic watermelon; filled diamonds, drought-stressed domestic watermelon. Data are mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05 (Yoshimura et al. 2008).

Potato plants expressing CLRAN1 formed more tubers than did non-transformants (NTs). In vitro cultures of potato plants were transferred to 1.3-L pots and grown in a greenhouse under supplementary halogen lamps for 91 days.

A sophisticated approach to improve potato productivity was introduced by Jonik et al. (2012). Their push approach consisted of suppressing starch synthesis in chloroplasts in source tissues to promote sucrose synthesis. In addition to this push strategy, the pull activity was promoted by overexpressing two plastid metabolite translocators, GPT and AdT. This strategy doubled the starch content of tubers without inhibiting photosynthesis in the source leaves.

In this context, one should revisit the very important research paper of Chen and Setter (2003), who analyzed the effect of light intensity and CO2 concentration at both the tuber-initiation and tuber-bulking stages. An increase in light intensity or atmospheric CO2 concentration at the tuber-bulking stage caused the fixed CO2 to accumulate exclusively in the tubers, while the same environmental conditions at the tuber-initiation stage resulted in shoot enlargement. Considering the above two studies, one could arrive at a promising strategy to increase potato yield. The best strategy would be to intensify photosynthesis in the source tissues from an early growth stage to the tuber-bulking stage, and enlarge the volumetric capacity of the sink tissues at the tuber-bulking stage.

To achieve increased yield, it is necessary to control the regulation of gene expression not only in specific tissues or regions but also at optimal developmental stages. If such enhancements of push and pull methods are successful, dramatic improvements in yield will be achieved. The explosive increase in the world’s population demands urgent action to overcome food and energy shortages. The substantial intensification of potato yield could help to solve these problems, because plant starch is an important feedstock as well as a food source (Bahaji et al. 2014).

This research was supported by the ALCA and CREST Programs of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.