2019 Volume 69 Issue 4 Pages 658-664

2019 Volume 69 Issue 4 Pages 658-664

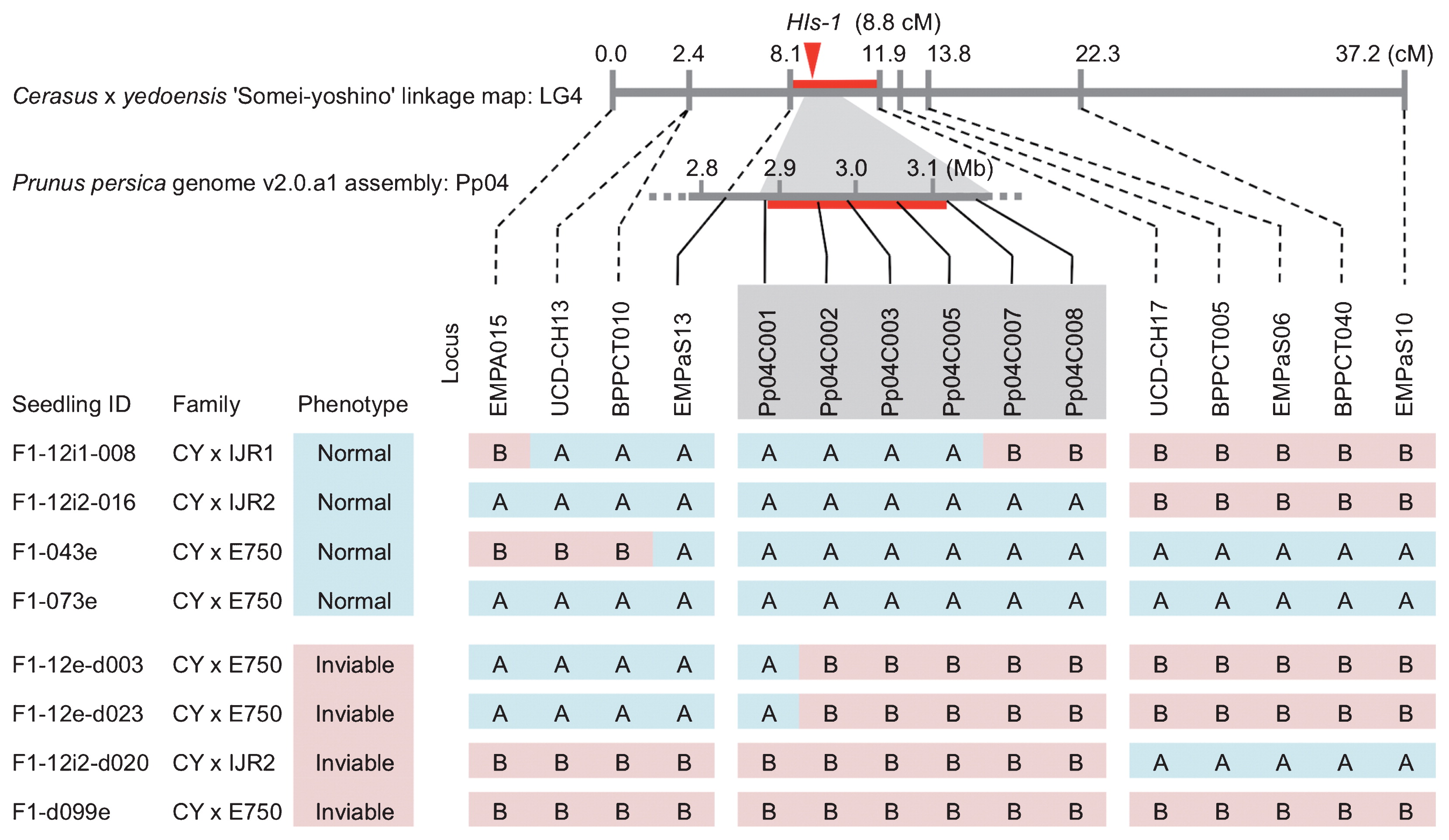

Flowering cherry is an extremely renowned ornamental tree, consisting of a variety of species and cultivars. Because cherry species have no strict barriers for interspecific hybridization before fertilization, identification of the gene underlying post-zygotic hybrid inviability will help breeders identify specimens for breeding and help us understand speciation mechanisms. In this study, we mapped the genetic linkages and physical genome sequences for a presumed hybrid inviability locus (HIs-1) that we observed in the seedlings crossed between Cerasus × yedoensis ‘Somei-yoshino’ and its wild relative C. spachiana. By the surveying linkage maps of ‘Somei-yoshino’ and C. spachiana, we identified correlation with seedling inviability only in linkage group 4 (LG4) of the ‘Somei-yoshino’ map. When we produced a finer-scaled map of HIs-1 in LG4, we found that HIs-1 is located between two microsatellite (SSR) markers with a 3.8 cM span. Using eight SSR markers based on peach genome sequences, we further refined the candidate region for HIs-1. This region was located between Pp04C001 and Pp04C007 markers, spanning 240 Kb of the peach genome, in which 45 transcribed genes had been estimated. From these candidate genes, it will be feasible to identify molecular mechanisms involved in cherry hybrid inviability.

Flowering cherry, belonging to the family Rosaceae, genus Cerasus or Prunus subgenus Cerasus, grows widely across the temperate region of the Northern Hemisphere. Approximately 10 wild species and over 300 cultivars are recognized in Japan, including one of the most popular cultivars Cerasus × yedoensis (Matsum.) Masam. et Suzuki ‘Somei-yoshino’ (Ohba et al. 2007). Some of these cultivars were produced via interspecific hybridizations. In addition, populations thought to be of hybrid origin are also observed in nature. Artificial pollinations among wild flowering cherries and between wild species and cultivars have shown considerable seed setting capacities (Tsuruta et al. 2012, Watanabe and Yoshikawa 1967). Here, similar pollen tube growth in pistils has been observed in every interspecific crossing (Tsuruta et al. 2012). These facts indicate that flowering cherry taxa are considered to exert no physiological barriers during pollination to fertilization in interspecific hybrids. Therefore, ecological isolation acting before pollination (e.g., spatial and temporal isolation, pollinator preferences) or reproductive barriers acting after fertilization (i.e., post-zygotic isolation, such as hybrid inviability [HI] or sterility) are essential for speciation in flowering cherries. Although ecological isolation has been well studied, only a few studies have identified genes and/or mechanisms involved in post-zygotic isolation and speciation (Bomblies and Weigel 2007, Rieseberg and Willis 2007). For example, complementary loss of duplicated genes (Bikard et al. 2009) and autoimmune response (Bomblies et al. 2007, Yamamoto et al. 2010) have been reported for model plants Arabidopsis and Oryza. Therefore, knowledge of reproductive isolating mechanisms is still very limited, especially in non-model woody plants.

In a previous study, we found that approximately half of the seedlings from progenies resulting from a cross between ‘Somei-yoshino’ and its wild relative (Cerasus spachiana Lavall. ex Ed. Otto) failed to grow (Table 1, Tsuruta and Mukai 2015). This trait was characterized as an arrested growth of seedlings after extension of the first true leaf, followed by death approximately one month after germinating (Fig. 1). When we constructed genetic linkage maps of both parents using the pedigree crossing between a ‘Somei-yoshino’ tree CY and a C. spachiana tree E750 (CY map and E750 map), we found that the seedling trait was only mapped in linkage group 4 (LG4) of the CY map. The seedlings that inherited one of the alleles located on a CY chromosome 4B (Chr-4B) had died. ‘Somei-yoshino’ (2n = 2x = 16 [Oginuma and Tanaka 1976]) has been thought to be a hybrid between C. spachiana and C. speciosa (Koidz.) H. Ohba based on morphological attributes (Takenaka 1963, Wilson 1916) and genetic analyses (Innan et al. 1995, Kato et al. 2014, Ohta et al. 2006, Tsuruta et al. 2017). Thus, the growth failure we observed may have been due to inbreeding depression between an ancestral C. spachiana of ‘Somei-yoshino’ and the pollen donor C. spachiana or an HI (more accurately, a “hybrid breakdown”) between C. speciosa and C. spachiana. If seedling inviability were caused by inbreeding depression with homozygous of deleterious alleles, the seedling trait should also have mapped on the same region of the paternal E750 map. Therefore, we concluded that the growth failure we observed was due to HI, and so named the locus as hybrid inviability of seedling 1 (HIs-1, Tsuruta and Mukai 2015). HIs-1 is located between two simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers EMPaS13 and BPPCT005 in LG4 of the CY map (3.9 cM), with tight linkage with EMPaS13 (Tsuruta and Mukai 2015). However, identification of HIs-1 genes has not yet been determined. Additionally, the maternal effect remains as a candidate for HIs-1 inviability due to a lack of reciprocal crosses (Tsuruta and Mukai 2015).

| Year | Pedigree | Number of seed | Seedling number | Number of seedlings used for genetic analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | Paternal | Normal growth (%) | Growth failure (%) | Unknown | Normal growth | Growth failure | ||

| 2016 | GRIF1 | CY | 250 | 92 (36.8) | 130 (52.0) | 28 | 40 | 49 |

| PEN1 | CY | 96 | 38 (39.6) | 44 (45.8) | 14 | 32 | 30 | |

| 2012a | CY | E750 | 118 | 37 (31.4) | 55 (46.6) | 26 | 30 | 33 |

| CY | IJR-1 | 131 | 50 (38.2) | 38 (29.0) | 43 | 46 | 25 | |

| CY | IJR-2 | 121 | 45 (37.2) | 65 (53.7) | 11 | 39 | 32 | |

| 2011a | CY | E750 | 302 | 78 (25.8) | 176 (58.3) | 48 | 77 | 101 |

Seedlings with normal growth (left side) and inviable growth (right side) of pedigrees between Cerasus × yedoensis ‘Somei-yoshino’ and C. spachiana at one month after germinating.

To clearly identify the HIs-1 region and candidate genes, we first tried to map them with a fine-scale linkage analysis using progenies from several crossing pedigrees and additional genetic markers located in LG4. Cherry species have relatively compact genomes, approximately 300 Mb (Arumuganathan and Earle 1991, Shirasawa et al. 2017, 2019). Thus, if fine mapping can narrow the HIs-1 region to under a 0.1-cM interval, then gene identification will be feasible. Recently, whole genome assemblages have been reported in some closely related Prunus species, such as Japanese plum (P. mume [Sieb.] Sieb. et Zucc. [Zhang et al. 2012]), peach (P. persica L. [International Peach Genome Initiative 2013]), sweet cherry (P. avium L. or C. avium [L.] Moench [Shirasawa et al. 2017]), and Korean flowering cherry (C. × nudiflora [Koehne] T. Katsuki et Iketani [Baek et al. 2018]). These data were of great use in constructing genetic markers on specific genome regions. The HIs-1 region has been narrowed further using genome sequence-based makers and so now has been placed into the Prunus genome. Then, we explored candidate genes of HIs-1 from the genome information. Our aim is to identify the gene and molecular mechanisms underlying HIs-1 and use these data to better understand why speciation and species diversity are maintained in flowering cherries.

In 2016, we artificially pollinated C. spachiana (GRIF1) and C. spachiana ‘Pendula’ trees (PEN1), planted in Gifu Prefecture Research Institution for Forest, as seed (maternal) parents and ‘Somei-yoshino’ tree from Gifu University (CY) as pollen (paternal) donors. Pollination procedures and seed handling protocols followed methods described by Tsuruta and Mukai (2015). In addition to the seedlings of GRIF1 × CY (N = 89) and PEN1 × CY (N = 62), we also used seedlings from crossings between CY and three individuals of C. spachiana (E750, IJR-1, and IJR-2) in 2012 for linkage analysis (CY × E750 [N = 63], CY × IJR-1 [N = 71], and CY × IJR-2 [N = 71]; Tsuruta and Mukai 2015). In all five pedigrees, we observed seedlings with the same growth failure phenotypes (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Fine mapping of seedling inviability lociWe extracted DNA from leaves of all parents and seedlings using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) or modified CTAB method. First, we selected 30 SSR loci that had already been mapped on a genetic linkage map for CY (from eight LGs) and genotyped for the GRIF1 × CY and PEN1 × CY pedigrees according to Tsuruta and Mukai (2015). We labeled some markers with universal fluorescence (Blacket et al. 2012) and tested the association between phenotype and genotype of seedlings on each locus with Fisher’s exact test.

We genotyped the following nine SSR markers (for all samples) that had been previously reported as occurring in LG4 in cherry species (Clarke et al. 2009, Olmstead et al. 2008, Tsuruta and Mukai 2015): BPPCT005, BPPCT010, BPPCT040 (Dirlewanger et al. 2002), EMPA015 (Clarke and Tobutt 2003), EMPaS06, EMPaS10, EMPaS13 (Vaughan and Russell 2004), UCD-CH13, and UCD-CH17 (Struss et al. 2003). Using segregation of CY alleles in seedlings of the five pedigrees, we constructed a fine linkage map of the CY LG4 using the pseudo-testcross method (Grattapaglia and Sederoff 1994). In this mapping strategy, offspring (F1 generation) from a crossing of highly heterozygous parents are used for the map construction of maternal and paternal parents. MapMaker/exp ver 3.0 (Lander et al. 1987) was used for linkage analysis with LOD = 2.6 and Rec = 40 cM. We mapped seedling inviability as a Mendelian trait locus.

Development of genome sequence-based SSR markers and graphical genotypingFrom a BLAST search result, we found that EMPaS13 (AY526629), an SSR marker tightly linked with HIs-1, corresponded to the region from the 5′-UTR to the 1st exon of the Prupe.4G058900 gene as estimated in Prunus persica Whole Genome Assembly v2.0 and Annotation v2.1 (Verde et al. 2017). We obtained almost 1 Mb P. persica genome sequences downstream from the Prupe.4G058900 gene. Of SSRs identified in that region, we chose eight SSRs with ~30–50 Kb interval for constructing markers. To amplify the SSR, we designed a primer set (Table 2) on mainly non-coding regions, such as intergenic spacer regions (IGSs), introns, and 5′-UTRs using Primer3Plus (Untergasser et al. 2012).

| Marker name | SSR motif | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Product size in ‘Somei-yoshino’ (bp)a | SSR position in scaffold_4 (base)b | Maker region (gene id) in peach genomeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pp04C001 | (CT)n | F: TCTTTGTCCCACAGATCCCA R: TGCTTGAATAAGGGAGACAGAG |

174/212 | 2,870,953 | Intergenic sequence region (IGS) and5′-UTR of Prupe.4G060200 gene |

| Pp04C002 | (GA)n | F: TCATTGCATGGGTGATGGCA R: TCTCTCCCCCTTCTCCAAGA |

202/214 | 2,949,313 | IGS between Prupe.4G061600 and Prupe.4G061700 |

| Pp04C003 | (CT)n | F: TTACACTCATTCCCCAAACTCT R: CATACCTCTCAGGCTCTCACTG |

140/144 | 2,984,682 | 5′-UTR of Prupe.4G062300 |

| Pp04C004 | (AG)n | F: CAGAGAACCTCTCTTCAACCTG R: TTTCACAAACACCTCTTGTGTC |

101 (monomorphic) | 3,009,361 | Coding regions (CDS) in Prupe.4G062700 |

| Pp04C005 | (TC)n | F: TTAATCTCCCACTTCACTTGCT R: GGTTTCAGTTCTCAAACTCTGC |

175/177 | 3,057,240 | 5′-UTR of Prupe.4G063700 |

| PpS4C006 | (CA)n(TA)n | F: CTTTTAGGGCATTAGACAGCAC R: CGCGCATTTGTATGTGATAA |

208 (monomorphic) | 3,086,981 | CDS.3 and 3rd intron of Prupe.4G064200 |

| Pp04C007 | (GA)n | F: TAATTGGAGGCAAAGACTAGGA R: CTGCCACAGACAATTAGACAAA |

145/171 | 3,113,086 | IGS and 5′-UTR of Prupe.4G064700 |

| Pp04C008 | (GA)n | F: GCCCAGATCAAACAACAGAAT R: CATGAAAGAGCATCTCAAGTCA |

194/210 | 3,155,731 | IGS and Prupe.4G065900 CDS.1 |

Of total 534 seedlings (356 seedlings of the five pedigrees [Table 1] and 178 seedlings of CY × E750 used for the map construction in Tsuruta and Mukai [2015]), recombinants between EMPaS13 and BPPCT005 markers and some non-recombinant seedlings were genotyped using constructed SSRs (Table 2) according to the above described method. Then we determined which allele located on chromosomes of CY (Chr-4A or Chr-4B) the seedling had inherited (described as A or B, respectively) and detected HIs-1 region (“graph genotype”). Lastly, we explored candidate genes of HIs-1 from the genome sequence of peach (Verde et al. 2017) and sweet cherry (Shirasawa et al. 2017).

In both pedigrees (GRIF1 × CY and PEN1 × CY) of the 30 loci we genotyped, we found that all loci located in LG4 (BPPCT005, BPPCT010, BPPCT040, EMPaS10, and EMPaS13) were closely associated with seedling inviability in the CY segregation (P < 0.0001; Table 3). The tightest association was observed in EMPaS13. Although other loci were also detected that correlated with the seedling trait rather weakly (P < 0.05), such as BPPCT002 and BPPCT004 in CY LG2 of GRIF1 × CY, this correlation was not consistent across pedigrees. Moreover, significant associations were never observed in the segregation of C. spachiana (GRIF1 and PEN1) alleles, except for CPPCT016 in PEN1 × CY (P = 0.042; Table 3). From the fine mapping of CY LG4, we located nine SSR markers in the 37.2 cM region. HIs-1 was mapped between the two SSR markers EMPaS13 and UCD-CH17 to within a 3.8-cM interval. The nearest marker with HIs-1 was EMPaS13, at a distance of 0.7 cM (Fig. 2).

| Linkage group | Position (cM)a | Locus name | Association (P valueb in Fisher’s exact test) for GRIF1 × CY seedlings | Association (P valueb in Fisher’s exact test) for PEN1 × CY seedlings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segregation of GRIF1 allele | Segregation of CY allele | Segregation of PEN1 allele | Segregation of CY allele | |||||||

| LG1 | 0.0 | CPPCT016 | 0.271 | n.s. | 0.662 | n.s. | 0.042 | * | 0.587 | n.s. |

| 28.1 | CPPCT027 | 0.391 | n.s. | 0.650 | n.s. | n.d. | – | 0.309 | n.s. | |

| 35.8 | UDP96-005 | n.d. | – | 0.636 | n.s. | n.d. | – | 0.612 | n.s. | |

| 46.7 | CPPCT026 | n.d. | – | 0.383 | n.s. | n.d. | – | 1.000 | n.s. | |

| 75.9 | BPPCT028 | 0.831 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | n.d. | – | n.d. | – | |

| LG2 | 26.9 | EMPA007 | 1.000 | n.s. | 0.665 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. |

| 45.9 | BPPCT004 | 0.191 | n.s. | 0.009 | ** | 0.469 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | |

| 49.2 | BPPCT002 | 0.133 | n.s. | 0.031 | * | 0.624 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | |

| 64.7 | pchgms1 | 0.135 | n.s. | 0.046 | * | n.d. | – | 0.603 | n.s. | |

| LG3 | 3.7 | EMPaS12 | n.d. | – | 0.221 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | 0.591 | n.s. |

| 29.0 | EMPaS05 | 1.000 | n.s. | 0.123 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | 0.358 | n.s. | |

| 41.1 | EMPA014 | 0.827 | n.s. | 0.017 | * | 0.291 | n.s. | 0.601 | n.s. | |

| LG4 | 0.0 | BPPCT010 | 1.000 | n.s. | 6.90e−13 | *** | 1.000 | n.s. | 2.32e−10 | *** |

| 6.8 | EMPaS13 | n.d. | – | 4.73e−20 | *** | 1.000 | n.s. | 2.00e−15 | *** | |

| 10.7 | BPPCT005 | 0.377 | n.s. | 2.20e−18 | *** | n.d. | – | 2.29e−13 | *** | |

| 20.2 | BPPCT040 | n.d. | – | 7.32e−13 | *** | n.d. | – | 7.43e−10 | *** | |

| 35.4 | EMPaS10 | 0.052 | n.s. | 2.02e−06 | *** | 1.000 | n.s. | 2.27e−05 | *** | |

| LG5 | 1.6 | BPPCT026 | n.d. | – | 0.664 | n.s. | 0.074 | n.s. | 0.575 | n.s. |

| 27.1 | BPPCT017 | n.d. | – | 0.828 | n.s. | 0.598 | n.s. | 0.286 | n.s. | |

| 30.3 | BPPCT037 | n.d. | – | 1.000 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | |

| 38.2 | BPPCT038 | n.d. | – | 1.000 | n.s. | n.d. | – | 0.642 | n.s. | |

| 45.0 | BPPCT014 | n.d. | – | 0.831 | n.s. | n.d. | – | 0.332 | n.s. | |

| LG6 | 7.8 | UDP96-001 | 0.824 | n.s. | 0.266 | n.s. | 0.061 | n.s. | 0.431 | n.s. |

| 21.1 | EMPA004 | 1.000 | n.s. | 0.616 | n.s. | 0.202 | n.s. | 0.441 | n.s. | |

| 26.4 | CPPCT023 | n.d. | – | 0.591 | n.s. | n.d. | – | 0.260 | n.s. | |

| 37.2 | UDP98-021 | 0.831 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | n.d. | – | n.d. | – | |

| LG7 | 45.8 | CPSCT033 | 0.831 | n.s. | 0.028 | * | 0.806 | n.s. | 0.118 | n.s. |

| 80.4 | CPPCT017 | 1.000 | n.s. | 0.513 | n.s. | 0.769 | n.s. | 0.774 | n.s. | |

| LG8 | 52.1 | CPPCT006 | 0.377 | n.s. | 0.144 | n.s. | 1.000 | n.s. | 0.772 | n.s. |

| 83.2 | AM287842 | 0.289 | n.s. | 0.521 | n.s. | 0.078 | n.s. | 0.611 | n.s. | |

Linkage map of LG4 of ‘Somei-yoshino’ (top), peach genome sequence of 4th chromosome (middle), and an example graphed genotype for the ‘Somei-yoshino’ allele in the normal and inviable seedling growth phenotypes (main table). Red lines indicate candidate regions; the arrow indicates the mapped position of HIs-1. In the graph genotype, alleles derived from ‘Somei-yoshino’ were represented. Blue (A) indicates Chr-4A and red (B) indicated Chr-4B alleles, both of which represent derivations of the ‘Somei-yoshino’ chromosome. HIs-1 location in the region between Pp04C001 and Pp04C007 was based on the correspondence between seedling phenotype and genotype.

We constructed eight pairs of primers to amplify SSR regions in the peach genome sequence (Table 2). All the SSR markers were successfully amplified in flowering cherry. Of the 534 seedlings, we genotyped 16 seedlings (normal growth [N = 8], growth failure [N = 8]) that has recombination between EMPaS13 and BPPCT005 and 14 non-recombinant seedlings (normal growth [N = 6], growth failure [N = 8]) with our developed genome sequence-based SSR markers, except for Pp04C004 and Pp04C006, due to homozygosity in CY (Table 2). We observed recombination between Pp04C001 and Pp04C002 in two growth failure seedlings and between Pp04C005 and Pp04C007 in a normal growth seedling (Fig. 2). We referenced the predicted function of genes located between Pp04C001 and Pp04C007 markers with the description registered in the Genome Database for Rosaceae (GDR: www.rosaceae.org/) and results from our BLAST search (Supplemental Table 1).

In this study, we mapped HIs-1, a locus presumably involved in post-zygotic interspecific reproductive barriers in flowering cherries, in detail with a genetic linkage map of CY, and associated it with a physical region of the Prunus genome. Even though flowering cherry is not a commonly commercialized woody species, the candidate region was straightforward to pinpoint due to the relatively compact size of its genome (~300 Mb) and an accumulation of available genetic makers, genes, and genomic information in related cultivated species.

From the HIs-1 mapping of two pedigrees of C. spachiana × CY, we only observed regular and tight correlation with seedling inviability in the LG4 of the CY map (Table 3). Thus, we decided that there was only one locus involved with seedling inviability in LG4 (i.e., HIs-1), the same outcome obtained in our previous study (Tsuruta and Mukai 2015). When we created a detailed map of LG4 of the CY map, we mapped HIs-1 to within a 3.8-cM interval, between the two SSR markers EMPaS13 and UCD-CH17. Using the genome sequence-based marker we developed, we found recombination between Pp04C001 and Pp04C002 and between Pp04C005 and Pp04C007 in some normal and inviable seedlings (Fig. 2). Thus, we detected the candidate region of HIs-1 as occurring between Pp04C001 and Pp04C007. Although we genotyped 534 seedlings of five pedigrees crossing CY and C. spachiana, we did not observe recombination in the candidate region between Pp04C002 and Pp04C005 and we could not narrow the HIs-1 region into any finer detail in our linkage map analysis.

The physiological mechanism responsible for seedling growth failure is still unclear. Post-zygotic HI is often predicted by a Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller model (Orr 1996, Rieseberg and Willis 2007), which postulates that HI is caused by deleterious interactions of two or more loci. However, we only found one locus that correlated with HI in our results. If seedling inviability is caused by heterozygosity of only one HIs-1 locus, we cannot explain the healthy growth of ‘Somei-yoshino’, which would be expected to have heterozygous alleles in HIs-1. Otherwise, his1, the deleterious allele of HIs-1, would be due to a somatic cell mutation occurring during grafting propagations across several generations. Alternatively, this may be a problem with the pedigrees, as described by Tsuruta and Mukai (2015). A few studies have shown a complex origin of ‘Somei-yoshino’ (Kato et al. 2014, Tsuruta and Mukai 2015, Tsuruta et al. 2017), not a simple F1 hybrid between C. speciosa and C. spachiana, but is instead a complicated hybrid such as BC1 or later generations. Actual parent species of ‘Somei-yoshino’ is still under debate. In the case of backcross progenies, if additional loci associated with HI may be homozygotes for both parental species alleles, then segregation and mapping of this locus might be undetectable. Further studies are needed using later generations or clear hybrid pedigrees.

Pp04C001 marker was located on the 5′-UTR of the Prupe.4G060200 gene, whereas Pp04C007 marker was located on the 5′-UTR of the Prupe.4G064700 gene in the 4th chromosome of peach genome (Table 2, Supplemental Table 1). By searching of sequence similarity with BLAST, we determined that these genes correspond to the Pav_sc0000037.1_g270.1.mk and Pav_sc0000506.1_g500.1.mk genes of P. avium. The region between these genes was approximately 240 Kb, where 45 transcribed genes are estimated to occur in the peach genome (Verde et al. 2017). On the other hand, the interval between the two genes was about 450 Kb across four scaffolds (Pav_sc0000037, Pav_sc0000816, Pav_sc0006298, and Pav_sc0000506) in the sweet cherry genome (Shirasawa et al. 2017). However, genes located in scaffold Pav_sc0000816 of sweet cherry genome have no homologous genes in the 4th chromosome of peach genome (Supplemental Table 1). Except for Pav_sc0000816, 49 transcribed genes were estimated in this region of the P. avium genome. Today, the genome data of ‘Somei-yoshino’ is also available in the Cherry Genome Database (Shirasawa et al. 2019). However, due to duplicated gene locations, gap existence, and contig arrangement difference between two phased genomes in the candidate region, we did not show results for the ‘Somei-yoshino’ genomes.

Interestingly, we found a Light-sensitive Short Hypocotyl (LSH) 10-like gene in the candidate region of both the peach and sweet cherry genomes in our candidate gene list (Supplemental Table 1). The LSH gene was first identified in Arabidopsis (LSH1: Zhao et al. 2004) and later in Oryza (G1: Yoshida et al. 2009). Now, the family is referred to as the Arabidopsis LSH and Oryza G1 (ALOG) gene family, and 10 ALOG genes are identified in Arabidopsis (Iyer and Aravind 2012). Physiological functions have been described for some ALOG genes including LSH1; these genes are expressed in the hypocotyl, shoot apical meristem, and leaf, and are believed to regulate plant growth or organ differentiation (e.g., Cho and Zambryski 2011, Li et al. 2012, Takeda et al. 2011, Yoshida et al. 2009, 2013, Zhao et al. 2004). The seedling growth failure that we observed is an arrested growth. If one of the ALOG genes in flowering cherry does not act the right way due to a genetic defect or abnormal regulation, seedling shoot might stop to grow. Therefore, the ALOG gene in the candidate region is a good candidate for HIs-1. We also found many genes that had a Leucinerich repeat (LRR) domain in the candidate region (Supplemental Table 1). Nucleotide-binding LRR genes are the most common genes for disease resistance in plants (Jones and Dangl 2006). These resistance genes sometimes triggered hybrid necrosis as an autoimmune response, interacting with the second locus from another strain in some plants (Bomblies et al. 2007, Bomblies and Weigel 2007, Yamamoto et al. 2010). Identifying the function and expression patterns of those candidate genes should uncover the gene actually underlying HI in flowering cherry. This result would provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying cherry speciation and species diversity.

M.T. designed and carried out the experiments and wrote manuscript. Y.M. provided critical advice for experiments and analysis. Both M.T. and Y.M. authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

We thank Chunlan Lian, Professor of Asian Natural Environmental Science Center, The University of Tokyo for the grateful suggestions for the manuscript, Gifu Prefecture Research Institution of Forest for providing the cherry trees for construct mapping pedigrees, and colleagues of the Laboratory of Forest Ecology of Gifu University for their help with artificial pollination. The authors also would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review. This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 18K14489.