2025 年 60 巻 1 号 p. 1-11

2025 年 60 巻 1 号 p. 1-11

Trials of several vaccines were conducted to identify a promising candidate vaccine for controlling the infectious disease nocardiosis caused by Nocardia seriolae in Japanese amberjack Seriola quinqueradiata. We investigated the pathogenicity and vaccine efficacy in an indoor aquarium facility with fish weighing 50 to 100 g. A live vaccine using a low-virulence isolate of N. seriolae screened from several N. seriolae isolates derived from infected fish conferred significant protection against the disease. However, neither an inactivated vaccine using formalin-killed cells, ultraviolet-treated bacteria, nor a DNA vaccine encoding the Ag85 gene provided significant protection. Sixty weeks trial demonstrated the long-term effectiveness of the live vaccine. These results indicate that a live vaccine is the most promising approach for controlling nocardiosis in Japanese amberjack.

Nocardiosis, a lethal granulomatous disease caused by aerobic actinomyces Nocardia spp., has been reported around the world in many fish species (Liu et al., 2023). The disease affects the skin and/or various inner tissues and results in characteristic lesions with abscesses in the epidermis and/or nodules in gills, kidney, and spleen (Liao et al., 2021). In Japan, infection with N. seriolae was first reported in cultured Seriola species, including Japanese amberjack S. quinqueradiata, greater amberjack S. dumerili, and yellowtail amberjack S. aureovittata (Kariya et al., 1968; Itano et al., 2006b), and the disease has been spreading primarily in western Japan (Liu et al., 2023). Mass mortality events of Seriola species infected with N. seriolae have caused significant economic losses in Japan, accounting for more than 40% of total yearly losses in these species (Matsuura et al., 2019). As export of amberjack to countries such as the United States and China (United States Department of Agriculture, https://fas.usda.gov/data/japan-japan-establishes-agricultural-export-expansion-strategy) has recently expanded due to increased global consumption, methods to effectively control nocardiosis are urgently needed.

Although antibiotic therapies against the disease using sulfonamides, including sulfamonomethoxine and sulfisozole sodium, are licensed in Japan (Yasuike et al., 2017), promising outcomes are not expected because N. seriolae is an intracellular pathogen (Hamaguchi et al., 1989) that is difficult to eliminate using these agents. Thus, long-term, repeated treatment is necessary to completely eliminate the pathogen (Ismail et al., 2012). Alternative methods for disease prevention, such as vaccines, are needed to avoid the development of antimicrobial resistance and reduce medication costs associated with the continuous use of antibiotics.

Efforts to develop a vaccine against nocardiosis have been made in several fish species, but no vaccines against the disease are currently in practical use. An inactivated vaccine using formalin-killed cells (FKCs) of N. seriolae conferred significant protection against experimental infection in ginbuna crucian carp Carassius auratus langsdorfii (Nayak et al., 2014). However, the FKC vaccine exhibited poor efficacy in Japanese amberjack (Shimahara et al., 2005), greater amberjack (Matsumoto et al., 2017), Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus (Kato et al., 2012), and largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides (Shimahara et al., 2010), suggesting that the efficacy of FKC vaccine is insufficient and varies by host species. Matsumoto et al. (2017) reported that recombinant interleukin (IL)-12 enhanced the effectiveness of the FKC vaccine against nocardiosis in greater amberjack. Trials of DNA and subunit vaccines have also been carried out in several fish species. Significant protection against nocardiosis was reported following injection of a plasmid encoding DNA derived from N. seriolae in greater amberjack (Kato et al., 2014) and hybrid snakehead Channa argus × C. maculate (Chen et al., 2019a; Chen et al., 2019b; Chen et al., 2020). Furthermore, promising effects were reported for subunit vaccines using recombinant nocardial antigens in protecting against nocardiosis in largemouth bass (Ho et al., 2018; Hoang et al., 2020; Hoang et al., 2021).

In contrast to next-generation fish vaccines, the protective effects of live vaccines against nocardiosis vary with the strain used for vaccination and with the vaccinated host. Itano et al. (2006b) reported that live vaccines using bacteria related to N. seriolae conferred limited or moderate protection in Japanese amberjack. Live attenuated vaccines prepared by UV treatment of pathogenic bacteria conferred strong protection (Li et al., 2022), whereas an attenuated vaccine established using gene knockout technology conferred only partial protection (Wang et al., 2022).

A promising vaccine against nocardiosis has yet to be developed for Japanese amberjack, a species that is more susceptible to the disease than other fish (Itano et al., 2006c). This lack of an effective vaccine has resulted in significant economic losses in Japan. The present study therefore evaluated the efficacy of several different vaccines against Nocardia, including conventional inactivated, DNA, and live vaccines. The objective was to facilitate the development of highly effective vaccines against nocardiosis in Japanese amberjack.

All experiments involving the use of fish in this study were planned and performed based on the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. Fish handling, husbandry, and sampling were also performed according to the policy designated by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fisheries Technology Institute and approved by the committee (approval no. 22003).

FishJuvenile Japanese amberjack were obtained from the Marine Fisheries Research and Development Center, Fisheries Research and Education Agency (Nagasaki, Japan) and raised for use in subsequent experiments. The fish were maintained in 500-L tanks with flow-through seawater at 22°C before use. Fish were fed twice daily with commercial pellets.

BacteriaInformation regarding each bacterial isolate used in the study, including N. seriolae and N. soli, is summarized in Table 1. Nocardia species of the isolate were identified using a confirmatory PCR method as described by Miyoshi and Suzuki (2003). Bacteria were cultured at 25°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (BD Biosciences) for 5 days. After culture, bacteria were centrifuged and then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% (w/v) Tween-80 (PBS-T) at 0.1 g (wet weight)/mL to adjust the concentration of bacterial cells at approximately 109 colony forming units (CFU) /mL. The bacterial suspension was mixed for 30 seconds using a vortex mixer (Scientific Industries) after zirconium beads (2 mm in diameter) were added to disperse clumped cells that appeared during the culture. The dispersed bacteria were diluted with PBS-T to adjust the concentration of cells just before use for vaccine preparation or experimental infection. Serial dilution and plating of bacteria on BHI agar was used to determine the number of CFU.

| Name | Year | Source | Location | Purpose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGN1266 | 2012 | greater amberjack | Kagoshima, Japan | Inactivated vaccine Experimental infection | Matsuura et al., 2020 |

| UTF1 | 2008 | Japanese amberjack | Miyazaki, Japan | Live vaccine trial | Yasuike et al., 2017 |

| KGN0711 | 2007 | Japanese flounder | Kagoshima, Japan | Live vaccine trial | *This study |

| KGN1028 | 2010 | Japanese flounder | Kagoshima, Japan | Live vaccine trial | *This study |

| KGN1218 | 2012 | Japanese flounder | Kagoshima, Japan | Live vaccine trial | *This study |

| KGN1405 | 2017 | Japanese flounder | Kagoshima, Japan | Live vaccine trial | *This study |

| MZ110901 | 2011 | Greater amberjack | Miyazaki, Japan | Live vaccine trial | *This study |

| FPC1073 | 2002 | Japanese amberjack | Oita, Japan | Live vaccine trial | *This study |

| §JCM11441 (N. soli) | ? | River water | Medmenham, UK | Live vaccine trial | Itano et al., 2006b |

Experimental infection tests were performed according to the immersion method or intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection method. The immersion method was performed as described by Matsuura et al. (2020). Briefly, fish were immersed in seawater containing N. seriolae for 10 min at 23–25°C without supply of additional seawater. For i.p. injection, 100 μL of N. seriolae inoculum was injected into the intraperitoneal cavity of naïve Japanese amberjack after anesthetization with 2-phenoxyethanol (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corp.).

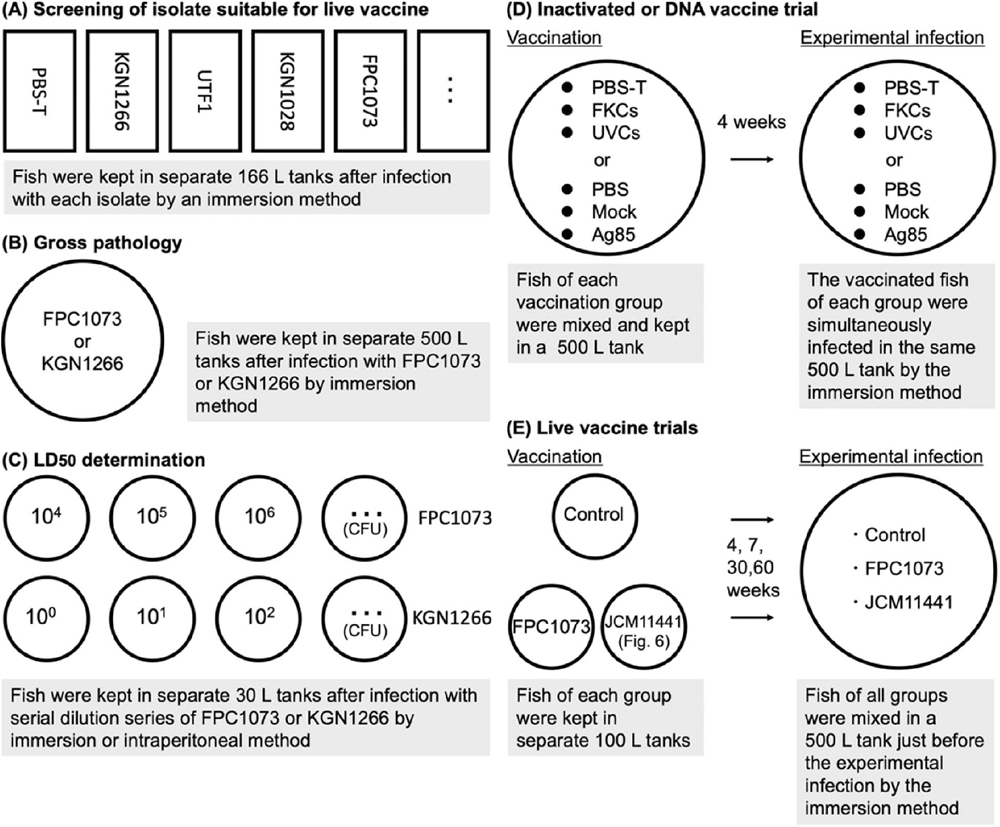

Evaluation of a low-virulence N. seriolae isolate as a live vaccineNaïve Japanese amberjack weighing 50–100 g were experimentally infected with the N. seriolae isolates adjusted to approximately 106 CFU/L, as shown in Fig. 1A. Actual concentration of the isolates KGN1266, UTF1, KGN0711, KGN1028, KGN1218, KGN1405, MZ110901, and FPC1073 was 5.2 × 106 CFU/L, 3.6 × 107 CFU/L, 1.6 × 107 CFU/L, 1.6 × 107 CFU/L, 3.7 × 107 CFU/L, 3.1 × 107 CFU/L, 4.4 × 107 CFU/L, and 8.7 × 106 CFU/L, respectively. The immersion method was used to screen for low-virulence N. seriolae isolates suitable for use as a live vaccine. Control fish were treated with the same volume of PBS-T instead of bacteria.

Naïve Japanese amberjack weighing 50–150 g were experimentally infected with 4.0 × 107 CFU/L or 1.0 × 104 CFU of N. seriolae FPC1073 by the immersion or i.p. method or 4.8 × 107 CFU/L of KGN1266 by the immersion method and then subjected to gross pathological examination. Doses of the experimental infection tests by the immersion method and i.p. method were determined according to previous studies in Matsuura et al. (2020) and Itano et al. (2006a), respectively. Infected fish were maintained in separate 500-L tanks, as shown in Fig. 1B, with flow-through seawater at 22–25°C. Live fish infected with the FPC1073 isolate and moribund fish infected with the KGN1266 isolate were anesthetized with 2-phenoxyethanol, euthanized by bleeding from the caudal vessel, and dissected for pathological analysis. The examination of both infected fish was performed 20 days after infection when moribund fish infected with the KGN1266 isolate suitable for the examination without concerns of postmortem changes was obtained.

Determination of virulence of N. seriolae isolatesThe virulence of isolates FPC1073 and KGN1266 was assessed by determining the respective lethal dose, 50% (LD50) values. Naïve Japanese amberjack weighing 50–100 g were experimentally infected using the immersion or i.p. method with 10-fold serial dilutions of FPC1073 or KGN1266. Infected fish were maintained separately in 30-L tanks with flow-through seawater at 22–25°C, as shown in Fig. 1C. Mortality of the infected fish was recorded daily. The cumulative mortality at the end of the infection test was used to calculate the LD50 value using GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software).

Vaccine preparation Inactivated vaccinesBroth-cultured N. seriolae strain KGN1266 was used as FKCs and ultraviolet-treated cells (UVCs). For preparation of FKCs, a broth culture supplemented with 0.3% formalin was incubated with shaking overnight at 25°C to kill the bacteria. For preparation of UVCs, cultured bacteria were washed once with PBS-T to remove medium components before UV treatment to prevent medium components from interfering with sterilization (Kollu and Örmeci, 2012). The washed bacteria were irradiated with 254-nm UV light at 5.0 J/cm2. The concentration of bacteria used to prepare FKCs and UVCs as measured before inactivation was 9.8 × 107 CFU/100 μL and 1.0 × 108 CFU/100 μL, respectively. The preparations were plated on BHI agar to confirm complete sterilization, and no live cells were detected.

DNA vaccineThe DNA vaccine was prepared as described by Kato et al. (2014) with slight modifications. A gene orthologous to Ag85 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which encodes a protective antigen, was used for the vaccine. The full-length sequence of the Ag85 gene (GenBank accession number: AB970641.1) was amplified using PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio) from genomic DNA extracted from N. seriolae KGN1266. Amplification was performed using sense primers containing 15-bp extensions homologous to the vector ends (5′-TTTGGCAAAGAATTCACCATGCGAGGCGATAGACGTCAGAG-3′ and 5′- CTGAGGAGTGAATTCTTACCCGATGTTCGCGGACAGATC-3′). The resulting amplicons were inserted into the vector pCAGGS (RIKEN BioResource Research Center) using In-Fusion HD Cloning Plus (TaKaRa Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocols and guidelines. The plasmid vector pCAGGS-Ag85 and an empty vector used as a mock control were purified using the PureYield Plasmid Midiprep System (Promega) and diluted to 20 μg/100 μL with PBS for subsequent vaccination tests.

Live vaccinesN. seriolae FPC1073 and N. soli JCM11441 were used for live vaccine tests. The inoculums containing 8.7 × 103 to 7.0 × 104 CFU of the bacteria were prepared just before vaccination.

Vaccine trials Inactivated vaccinesNaïve Japanese amberjack weighing 50–100 g were anesthetized with 2-phenoxyethanol and then injected i.p. with 100 μL of inactivated vaccine. Control fish were injected with the same volume of PBS-T instead of vaccine. The fish in the various vaccine groups were labeled using Visible Implant Elastomer (VIE) tags (Northwest Marine Technology, Inc.) of different colors and maintained in 500-L tanks with flow-through seawater at 22–25°C, as shown in Fig. 1D. At 4 weeks after vaccination, the fish were experimentally infected with 8.5 × 106 CFU/L of the virulent strain KGN1266 via the immersion method. Mortality of the infected fish was recorded daily.

DNA vaccineNaïve Japanese amberjack weighing 50–100 g were anesthetized with 2-phenoxyethanol and then injected with DNA vaccine in the dorsal muscle, whereas control fish were injected with the same volume of PBS or empty vector (mock). The fish in the various groups were labeled with different-colored VIE tags and maintained with flow-through seawater at 22–25°C, as shown in Fig. 1D. At 4 weeks after vaccination, the fish were infected with 8.8 × 107 CFU/L of the virulent strain KGN1266 via the immersion method. Mortality of the infected fish was recorded daily.

Live vaccinesNaïve Japanese amberjack weighing 50–100 g were anesthetized with 2-phenoxyethanol and then injected i.p. with 100 μL of the live vaccine preparation. Control fish were injected with the same volume of PBS-T. The fish in each group were labeled with different-colored VIE tags and maintained with flow-through seawater at 25°C, as shown in Fig. 1E. Four to sixty weeks after vaccination, the fish of the vaccinated and control groups were mixed and experimentally infected with 2.3 × 107 to 8.4 × 107 CFU of the virulent strain KGN1266 via the immersion method. Mortality of the infected fish was recorded daily.

Statistical analysesVaccine efficacy was evaluated based on the relative percent survival (RPS), which was calculated according to the method of Amend (1981), and differences in survival time were analyzed using the log-rank test (Bland and Altman, 2004). All Statistical analyses in the study were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Survival percentage of fish in the FKC and UVC vaccinated groups was 15.0% and 35.0%, respectively, whereas that of the control group was 30.0% (Fig. 2). Vaccination had no significant effect on survival time. Relative to the control group, the RPS of fish treated with the FKC and UVC inactivated vaccines was –21.4% and 7.1%, respectively, indicating that the vaccines did not provide a protective effect against the disease. The DNA vaccine prepared using the Ag85 antigen gene of N. seriolae did not exhibited significant protection against subsequent bacterial challenge. Relative to the control group, the RPS of the vaccinated group was 10.0%, and the survival time was not significantly affected by vaccination (Fig. 3). No mortality or signs of nocardiosis were observed in any of the vaccinated groups during the vaccination phase.

Survival percentage of fish vaccinated with formalin-killed cells (FKCs) or ultraviolet-treated cells (UVCs) was recorded after experimental infection with the virulent N. seriolae strain KGN1266. Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test with Bonferroni correction (n = 20).

Survival percentage of fish vaccinated with the DNA vaccine encoding the Ag85 gene was recorded after experimental infection with the KGN1266 strain. Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test with Bonferroni correction (n = 10).

No fish died due to infection with the FPC1073 isolate, although infection with the other isolates did result in mortality (Fig. 4A). No gross pathology analyses were performed in the trial due to concerns over postmortem changes. We performed additional experimental infection tests using the FPC1073 isolate in addition to KGN1266, the virulent strain used for vaccine trials in the present study for following gross pathology analyses using live fish or moribund fish infected with the FPC1073 or KGN1266, respectively. No lesions typical of nocardiosis were observed in fish infected with the FPC1073 isolate, although nodules were observed in the gills, pyloric cecum, spleen, and kidney, in addition to skin abscesses in fish infected with the virulent KGN1266 strain (Fig. 4B‒Q). The LD50 for FPC1073 estimated using the immersion method was not determined because no fish died with the infection with ~1.1 × 108 CFU/L of the isolate, whereas that for the KGN1266 strain was 5.16 × 106 CFU/L (Fig. 5A and B). The LD50 values for FPC1073 and KGN1266 estimated according to i.p. infection were 1.32 × 107 CFU/mL and 1.22 CFU/mL (Fig. 5C and D), respectively, thus confirming that FPC1073 was a low-virulence strain.

(A) Cumulative mortality of fish experimentally infected with each N. seriolae isolate via the immersion method (n = 10).

(B–Q) Photographs of fish experimentally infected with FPC1073 (B–K) or KGN1266 (L–Q). Fish were infected with FPC1073 (B–F) or KGN1266 (L–Q) using the immersion method and infected with FPC1073 (G–K) using the intraperitoneal method and then euthanized and dissected. Dashed lines indicate nodules formed on the gill (L), pyloric cecum (M), spleen (N), and kidney (O). Arrows indicate skin abscesses (P, Q).

Cumulative mortality of fish infected by immersion (A, B) or i.p. method (C, D) with ten-fold serial dilution series of N. seriolae FPC1073 (A, C) or KGN1266 (B, D). The median lethal dose (LD50) was calculated by the results.

Live vaccine trials were performed using the low-virulence isolate FPC1073. Inoculation doses of the vaccines were set to be approximately 104 CFU/fish because lesions typical of and death caused by nocardiosis were not observed in the infected fish with 1.0–1.8 × 104 CFU of FPC1073 (Figs. 4G–K and 5C). The RPS of the FPC1073-vaccinated group was 85.7%, and the survival time of the vaccinated group was significantly longer than that of the control group (p < 0.001 by log-rank test, Fig. 6). The live N. soli (JCM11441) vaccine was significantly less protective than the FPC1073 live vaccine (p < 0.05 by log-rank test, Fig. 6). The RPS of the JCM11441-vaccinated group was 28.6%. No mortality or signs of nocardiosis were observed in any of the vaccinated groups during the vaccination phase.

Survival percentage of fish vaccinated with 7.0 × 104 CFU or 4.0 × 104 CFU of FPC1073 (N. seriolae) or JCM11441 (N. soli), respectively. Mortality was recorded after experimental infection with 7.6 × 107 CFU/L of KGN1266 strain at 4 weeks post-vaccination using the immersion method. Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test with Bonferroni correction (*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001) (n = 15).

The RPS of the vaccinated group over a period of 7, 30, and 60 weeks was 87.5%, 83.3%, and 91.7%, respectively (Fig. 7). For all vaccinated groups, the survival time was significantly longer than that of the respective vaccine control group; thus, protection extended for at least 60 weeks post-vaccination. No mortality or signs of nocardiosis were observed in any of the vaccinated groups during the vaccination phase.

Survival percentage of fish vaccinated with 1.2 × 104 CFU (A), 8.7 × 103 CFU (B), or 5.0 × 104 CFU (C) of the FPC1073 isolate was recorded after experimental infection with 8.4 × 107 CFU/L (A), 2.3 × 107 CFU/L (B), or 5.5 × 107 CFU/L (C) of strain KGN1266 at 7 (A), 30 (B), or 60 (C) weeks post-vaccination using the immersion method. Statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test (***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001); n ≥ 8 (A), n = 12 (B), and n ≥ 12 (C).

In the present study, we successfully identified a low-virulence N. seriolae isolate suitable for use as a live vaccine. The RPS values of the strain FPC1073 vaccine examined in this study and other promising vaccines reported in previous studies were 85.7% and 94.9% (DNA vaccine for greater amberjack (Kato et al., 2014)), 83.1% (DNA vaccine for the hybrid snakehead (Chen et al., 2020)), and 89.7% (live vaccine for hybrid snakehead (Li et al., 2022)), respectively. Thus, the present live vaccine using strain FPC1073 exhibits a similar protective effect against infection compared with other vaccines. We also evaluated the safety of the vaccine using experimental infection tests. The LD50 of strain FPC1073 in Japanese amberjack was markedly lower than that of the more virulent strain KGN1266 although high-dose i.p. injection of FPC1073 caused mortality in some injected fish. Furthermore, infection with strain FPC1073 via immersion did not cause the death of challenged Japanese amberjack or the development of typical lesions such as skin abscesses or nodules, as observed in fish infected with the KGN1266 strain. Intraperitoneal infection with strain FPC1073 at the same dose used for vaccination did not cause death or any disease symptoms, suggesting that the virulence of the isolate was substantially lower than that of previously reported low-virulence N. seriolae isolate SN02-05 in Japanese amberjack (Itano et al., 2006b). Therefore, the appropriate dosage of the live vaccine using strain FPC1073 is a promising tool for safely controlling nocardiosis in Japanese amberjack.

The effectiveness of the live vaccine using strain FPC1073 was surprisingly long lasting, persisting for at least 60 weeks after vaccination. This is the first report demonstrating the long-term efficacy of a live vaccine against fish nocardiosis. Vaccination using live vaccines mimics the natural infection process and generally induces a longer-lasting immune response than inactivated vaccines, without the need for booster shots (Shoemaker et al., 2009). In catfish Ictalurus punctatus, the protective effect of a live vaccine against the intracellular bacterium Edwardsiella ictaluri persisted for 4 months (Klesius and Shoemaker, 1997). Kaveh et al. (2014) reported that effector memory CD4+ T cells which were continually primed by persistent live cells of Mycobacterium bovis BCG (acid-fast bacteria that possess thick and lipid-rich layers in the cell wall, similar to Nocardia (Lechevalier et al., 1971)) were responsible for long-term protection against the BCG infection in mouse. In contrast to the mouse study, the mechanism of long-term protection in fish have not been demonstrated due to the lack of related studies. Further studies on the persistence of the live FPC1073 cells and their effect on immune responses responsible for long-term protection are required. In contrast to live vaccines, the protective effect of inactivated vaccines against Streptococcus agalactiae and Aeromonas salmonicida in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Pasnik et al., 2005) and Atlantic salmon Salmo salar (Bricknell et al., 1999) reportedly persisted for only 6 and 9 months, respectively. Bricknell et al. (1999) also reported that the vaccination-induced host antibody response against the pathogen decreased over time.

In mammals, DNA vaccines have been shown to induce vigorous cell-mediated immune responses, key responses to eliminate the intracellular pathogen (Matsuura et al., 2020), whereas conventional inactivated vaccines normally fail to stimulate such responses (Felgner, 1998; Huygen et al., 1996). Kato et al. (2014) reported that a vaccine encoding the Ag85 gene conferred significant protection against N. seriolae infection in greater amberjack, a species related to Japanese amberjack. In the present study, however, the vaccine encoding the Ag85 gene did not provide significant protection against nocardiosis in Japanese amberjack, as mentioned above. We suspect that differences in the route of experimental infection in these vaccine trials were responsible for the discrepancy in results. We performed experimental infection via the immersion method in the present study, whereas intramuscular or intraperitoneal infection was employed in previous studies (Chen et al., 2020; Kato et al., 2014). Itano et al. (2006a) studied the changes in disease symptoms related to different infection routes and demonstrated that the immersion route, which most closely mimics the natural route of infection, is more appropriate than injection methods for reproducing natural infections. Further studies are required to determine the reasons for differences in vaccine efficacy among fish species in order to develop a promising DNA vaccine suitable for Japanese amberjack. Chen et al. (2020) reported promising results in hybrid snakehead for DNA vaccines encoding other genes. Exploring the promising candidate genes for DNA vaccine for which DNA vaccines could be effective in Japanese amberjack is another issue to be addressed.

Formalin-inactivated vaccines, which have been the most frequently used type of vaccine for cultured fish worldwide, reportedly do not induce adequate protection against nocardiosis in fish (Shimahara et al., 2005). In addition to FKCs, we tested bacteria inactivated using other methods because we suspected that some N. seriolae antigens essential for enhancing specific immune responses are denatured by formalin. A previous study of Mycobacterium species showed that glycolipids, including mycolate, contribute to inducing acute and memory immune responses to tuberculosis caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Ishikawa et al., 2009). Matsumoto et al. (2018) reported that glycolipids could not be extracted from FKCs of either Mycobacterium sp. or N. seriolae, suggesting that the glycolipids were degraded by formalin treatment. They also demonstrated that the glycolipids extracted from live cells partially enhanced protection induced by a FKC vaccine against N. seriolae. In an attempt to reduce the risk of vaccine antigen denaturation by chemical treatment, we prepared UVCs without any chemical treatment or heating; however, N. seriolae UVCs did not induce a protective effect in this study. Electromagnetic waves of short wavelength and high frequency, such as those produced by UV light and γ-rays, produce high levels of energy that inactivate (i.e., kill) pathogens. Salk et al. (1940) demonstrated that UV irradiation inactivated the influenza virus without affecting vaccine antigen potency. Rae et al. (2008) reported that the morphology, surface structure, and immunogenicity of cowpea mosaic virus were retained following UV irradiation (Langeveld et al., 2001). Vaccine trials of UV-treated pathogens have been reported in mammals. UV-treated vaccines for polio virus and Fusobacterium nucleatum were shown to confer protection against infection by these pathogens (Hughes et al., 1979; Liu et al., 2009).

In addition to efficacy, manufacturing costs also play an important role in determining the practicality of a vaccine. The live vaccine against nocardiosis using our established strain is promising in terms of cost because it can be easily and inexpensively produced, whereas new vaccine platforms, including DNA and subunit vaccines, are generally expensive to produce due to considerable time and effort requirements. In the case of other promising vaccines against nocardiosis, such as DNA vaccines (Kato et al., 2014), subunit vaccines (Ho et al., 2018), and an FKC vaccine supplemented with IL-12 (Matsumoto et al., 2017), higher production costs are expected due to the requirement for further purification of the DNA or recombinant protein (Shoemaker et al., 2009). The safety of a vaccine must also be confirmed before it is placed into practical use; therefore, we are currently evaluating safety concerns related to a live vaccine, such as the risk of reversion to virulence (Te Yeh et al., 2020) and long-term latency of the live vaccine strain which has a potential for reactivation causing clinical symptoms and mortality in vaccinated fish. Managing the risk of the latent infection caused by the live vaccine is also important to ensure the safety of food products in fish farms. In addition, further studies to evaluate the reason for the low virulence of the vaccine strain in the host are needed including a comparison of histopathological changes in fish infected with a virulent isolate and a high dose of the FPC1073 isolate and a physiological and/or biochemical characterization of the strain.

We thank Mr. Soetsu Yanagi (Kagoshima Prefectural Fisheries Technology and Development Center, Kagoshima, Japan) for providing the KGN1266, KGN0711, KGN1028, KGN1218, and KGN1405 isolates. We also thank Prof. Terutoyo Yoshida (Faculty of Agriculture, University of Miyazaki, Miyazaki, Japan), Mr. Takayuki Minami (Miyazaki Prefectural Fisheries Research Institute, Miyazaki, Japan), and Dr. Yutaka Fukuda (Oita Prefectural Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research Center, Oita, Japan) for providing the UTF1, MZ110901, and FPC1073 isolates, respectively. Strain JCM11441 was obtained from the Japan Collection of Microorganisms, RIKEN BRC, which is a participating partner in the National BioResource Project of the MEXT, Japan.

This study was funded in part by the Food Safety and Consumer Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan, and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 22K14952).