2022 年 10 巻 2 号 p. 47-51

2022 年 10 巻 2 号 p. 47-51

The patient was a 38-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1. Labor started at 40 weeks of gestation. Labor induction was initiated due to uterine inertia, and as fetal distress was observed, vacuum extraction was performed along with the Kristeller maneuver. Just after delivery, decreased blood pressure and hematuria were observed, and the patient was urgently transported to our hospital. Upon arrival, hematoma formation was noted in the bladder. Ultrasound on postpartum day 4 confirmed the formation of a vesicouterine fistula. The patient was diagnosed with unscarred uterine rupture and bladder rupture and underwent surgery. In this case, the external force applied to the uterus during delivery was presumed to be the cause of unscarred uterine rupture and bladder rupture. If hypotension or hematuria is observed during delivery, it is important to consider the possibility of unscarred uterine rupture and bladder rupture when managing the condition.

Uterine rupture is an obstetric complication with high fetal and maternal mortality rates,1) making early diagnosis and treatment essential. Uterine rupture is caused mainly by scarring in the uterus. Incidence rates vary by region, with studies conducted in Japan from 2011 to 2015 reporting an incidence rate of 0.015%.2) The most frequent symptom of uterine rupture is acute abdomen. Other symptoms include vaginal bleeding, changes in circulatory dynamics, and arrested labor.3) Uterine rupture is classified as either scarred or unscarred. According to a report by Nurullah et al.,4) the incidence of unscarred uterine rupture is 1 in 2,770 deliveries. Reported risk factors for unscarred uterine rupture include oxytocin use, multiparity, uterine adenomyosis, uterine malformation, fetal abnormality, and macrosomia.1,4,5,6) Unscarred uterine rupture complicated by bladder rupture is even rarer. Here we report our experience with a difficult-to-diagnose case of unscarred uterine rupture complicated by bladder rupture following vacuum extraction delivery.

A 38-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1 delivered a full-term baby via vaginal delivery. Her medical and family histories were unremarkable. Pregnancy was achieved by intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and the course of pregnancy was unremarkable. At 40 weeks and 5 days of gestation, the patient was hospitalized at another clinic. The patient requested painless labor, and epidural anesthesia was introduced at 6 cm of cervical dilation. At 9 cm of cervical dilation, labor induction was initiated due to secondary uterine inertia. The cervix reached full dilation, and birth crowning occurred at 4 hours and 15 minutes into labor. Prolongation of the second stage led to the decision to carry out forced delivery, and vacuum extraction was performed. With concomitant use of the Kristeller maneuver, the infant was delivered after two tractions without slippage. The infant was a boy weighing 3,552 g, with Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. At the completion of perineal tear repair, total blood loss was 350 ml and blood pressure was 110/74 mmHg. Blood pressure 2 hours after delivery was 89/53 mmHg. Although persistent hematuria was observed, transabdominal ultrasonography showed no intraperitoneal hemorrhage. However, as facial pallor and hypotension persisted, the patient was diagnosed with postpartum shock of unknown cause and was emergently transported to our hospital (Figure 1).

Pregnancy course at previous hospital.

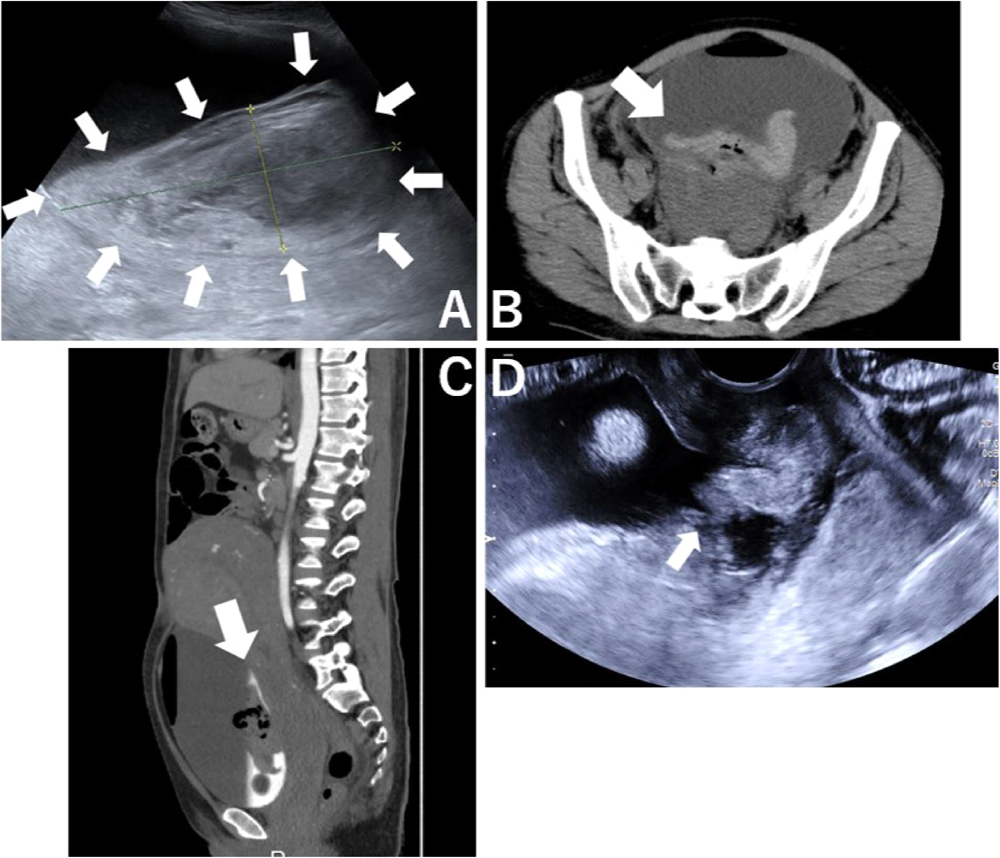

Vital signs on arrival were as follows: blood pressure, 86/60 mmHg; pulse, 84 beats/min; and shock index, 1. Examination on arrival revealed accumulated blood clots in the vagina without persistent uterine bleeding, and transabdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of bleeding in the intraperitoneal cavity. As there was a finding suggestive of blood accumulation in the bladder (Figure 2A), bladder irrigation was performed to prevent urinary retention. No flow of urine or saline into the vagina was observed during the procedure. Examination following bladder irrigation revealed re-accumulation of blood clots, indicating persistent bleeding in the bladder. Therefore, four units of red blood cells were transfused. Her vital signs were still unstable despite blood transfusion, and hypotension was observed 8 hours after arrival. As persistent bleeding in the bladder was suspected as the cause, contrast-enhanced CT was performed to further examine the source of bleeding (Figure 2B, 2C), which revealed a 9-cm hematoma in the bladder. However, since it was difficult to assess for bladder injury or uterine rupture, a definitive diagnosis of uterine rupture could not be made. On the basis of minimal ascites in the peritoneal cavity, intraperitoneal hemorrhage was considered unlikely. Therefore, we decided to continue managing the condition through transfusion and bladder irrigation.

A: Transabdominal ultrasound on arrival at our hospital; arrows indicate findings suggestive of blood accumulation in the bladder.

B, C: Contrast-enhanced CT (C: horizontal, D: sagittal); arrow indicates a 9 cm hematoma in the bladder.

D: Transvaginal ultrasound at postpartum day 4; arrow indicates a hyperechoic area extending from the uterine cervix to the bladder.

Urinary catheter occlusion was noted on postpartum day 4, and transvaginal ultrasound revealed a hyperechoic area extending from the uterine cervix to the bladder, which raised suspicion of a tear of the uterine muscle (Figure 2D). Persistent flow of thin bloody fluid was also observed in the vagina. Therefore, rupture of the bladder and rupture of the uterus immediately beneath it were suspected. Transvaginal ultrasound findings showed no continuity of the myometrium, and on internal examination a finger passed from the uterus into the bladder and touched the balloon of the intravesical catheter. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of unscarred uterine rupture with bladder rupture was made, and an emergency laparotomy was planned. Cystoscopic bilateral ureteral stent placement, simple total abdominal hysterectomy, and bladder repair were performed intraoperatively. On cystoscopy performed prior to laparotomy, there was no damage to the bilateral ureteric orifices, and the tear was located between the right and left ureteric orifices, which extended to the cervical canal. Laparotomy revealed a large amount of blood clots in the vesicouterine pouch. The clots were removed, the field of view was expanded, and uterine rupture was found on the anterior wall of the cervix. Since preservation of the uterus was deemed impossible, hysterectomy was performed first, and the visual field was secured to allow the urologist to evaluate the site of bladder injury. The wound was closed using a double-layer suture. The duration of surgery was 205 minutes and intraoperative blood loss was 1,810 ml. Intraoperative findings did not show blueberry spots in the bladder suggestive of pelvic endometriosis. Pathology of the removed uterus showed bleeding from the ruptured site (Figure 3).

Pathological pictures of the uterus.

A: Front view of macro image; arrow indicates fracture area.

B: Rear view of macro image.

C: Circumcised surface of the cervix.

D: Micrograph of the red frame in image C; arrow indicates bleeding site.

The postoperative course was favorable. Cystography was performed on postoperative day 16 to confirm the absence of hemorrhage and fistula. The ureteral stent and urethral catheter were subsequently removed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital.

Unscarred uterine rupture complicated by bladder rupture is extremely rare. In the present case, the patient underwent vacuum extraction delivery combined with the Kristeller maneuver, which led to rupture of the unscarred uterus and bladder. Macroscopic hematuria and hypotension were also observed. Contrast-enhanced CT was performed, but did not lead to a definitive diagnosis. On transvaginal ultrasound performed on postpartum day 4, unscarred uterine rupture and bladder rupture were suspected. The diagnosis was made using pelvic examination and contrast-enhanced MRI. Through our experience with this case of uterine rupture and bladder rupture, we explored methods for early diagnosis and causes of these conditions.

When considering diagnostic methods for uterine rupture and bladder rupture, we also consider their symptoms. In 2010, Ho et al.7) reported cases of uterine rupture and bladder rupture that occurred during vaginal delivery in patients with a history of cesarean section. They stated that 23 similar cases have been reported since 1991. They also reported that macroscopic hematuria was the most common sign. The report further indicated that: (1) the possibility of uterine rupture and bladder rupture should be considered in patients with a history of cesarean section even after successful vaginal delivery; (2) if macroscopic hematuria is observed, a Foley catheter should be placed to monitor the degree of hematuria and urinary outflow; and (3) if macroscopic hematuria is followed by other symptoms, cystoscopy should be performed. To date, the most frequent symptom of bladder rupture is macroscopic hematuria, and bladder rupture should be suspected if macroscopic hematuria is noted, regardless of whether a scarred or unscarred uterus is present.

Bladder rupture and uterine rupture are associated with high fetal and maternal mortality rates, and early diagnosis is essential if suspected. In the case of scarred uterine pregnancy reported by Tomoyuki et al.,8) lower abdominal pain was observed at 34 weeks of gestation, but the patient’s vital signs were stable with no abnormal test results. However, upper abdominal pain was subsequently observed, and CT examination revealed the presence of ascites. An emergency cesarean section was performed, which revealed rupture of the anterior wall of the uterus, and the tear was covered by the intestinal tract. Thus, many cases are difficult to diagnose due to the lack of symptoms. If a patient complains of abdominal pain, uterine rupture should be considered, even in the absence of symptoms such as genital hemorrhage and hypotension. If necessary, the use of CT scans and other imaging modalities should be considered. In the present case, uterine rupture and bladder rupture were suspected on transvaginal ultrasonography. For early diagnosis, the use of transvaginal ultrasound to confirm uterine wall rupture was also considered important.

In 1992, Dagher et al.9) reported the mechanism of uterine rupture complicated by bladder rupture. According to their study, in most of the patients who had a prior cesarean section, significant adhesion occurred between the thinned anterior wall of the lower uterus and the bladder wall, causing poor uterine extension. This leads to uterine rupture, which also affects the bladder and eventually causes bladder rupture. We investigated cases of unscarred uterine rupture complicated by bladder rupture. In a case reported by Zeteroglu et al.,7) no uterotonic agent or forced delivery was used. However, the cause was presumed to be labor managed by a traditional midwife without sufficient education. Our case differs from this one. We consider the rupture of the bladder and uterus to have been caused by the use of uterotonics and forced delivery, combined with the Kristeller maneuver. All of these procedures apply force to the uterus, and excessive force can potentially cause unscarred uterine rupture and bladder rupture. We also examined cases with a scarred uterus that had bladder rupture during vaginal delivery and found that most of these cases used uterotonics. This also suggests that excessive uterine contractions may be a cause of bladder rupture.8) It has also been suggested that epidural anesthesia may delay the diagnosis of uterine rupture, but this has been ruled out.10)

As mentioned above, unscarred uterine rupture complicated by bladder rupture is extremely rare and difficult to diagnose. In cases exhibiting macroscopic hematuria accompanied by decreased blood pressure, ultrasound should be actively performed to determine the cause. To prevent uterine rupture and bladder rupture, it is important to use an appropriate uterotonic agent, perform the Kristeller maneuver correctly, and ensure adequate traction at the time of vacuum extraction and forceps delivery.

In conclusion, we encountered a case of unscarred uterine rupture complicated by bladder rupture following vacuum extraction. Trauma to the urinary tract, including the bladder, can cause macroscopic hematuria and decreased blood pressure during delivery. If bladder injury is suspected, abdominal ultrasound or cystoscopy should be considered. In particular, when using a delivery procedure involving the application of external force, such as the Kristeller maneuver and vacuum extraction/forceps delivery, the potential for rupture of the uterus and bladder should be kept in mind even in patients with an unscarred uterus.

None to report.

None to report.