2019 年 7 巻 1 号 p. 9-15

2019 年 7 巻 1 号 p. 9-15

Numerous trial-and-error approaches have been taken to achieve effective hemostasis for difficult obstetrical uterine hemorrhage cases. In the field of obstetrics, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is known to be highly effective for controlling uterine hemorrhage and hematoma. This procedure achieves a high hemostasis rate, and the frequency of hysterectomy has thus sharply decreased. Although arterial ligation for massive hemorrhage at the time of cesarean section may fail to control bleeding in a number of cases due to an abundance of collateral circulation pathways, various new hemostatic techniques such as compression sutures of the uterus, uterine tamponade with gauze or a balloon, and intraoperative TAE have become available. However, complications including subsequent endometrial hypoplasia, menstruation disorder, infertility, pregnancy loss, placenta accreta, and uterine rupture have been reported even in cases undergoing successful hemostasis with TAE using absorbable embolus. Against this backdrop, we reconsidered fertility-preserving hemostatic strategies for critical obstetrical hemorrhage under these circumstances, and herein discuss how to select the optimal strategy based on our knowledge of and experience with various hemostatic procedures.

The maternal mortality rate in Japan had been decreasing steadily until 2007 (3.1/100,000 total births), but thereafter showed a fluctuating pattern. The rate of 2.7/100,000 total births in 2014 increased to 3.4/100,000 total births in 2016.1) The major causes of maternal deaths include, in descending order of frequency, critical obstetrical hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism, aortic vessel disease, respiratory disease, and infectious disease, with obstetrical uterine hemorrhage ranking first. The causes of critical obstetrical hemorrhage, in descending order of frequency, were uterine type amniotic fluid embolism [with major signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)], uterine rupture, atonic hemorrhage, premature separation of normally implanted placenta, and uterine inversion. Management and prevention of hemorrhage are still important clinical challenges.1,2)

Numerous trial-and-error approaches have been taken to secure effective hemostasis for difficult obstetrical uterine hemorrhage cases.2) Various surgical hemostatic procedures including arterial ligation, supravaginal amputation of the uterus, and hysterectomy, in addition to procedures such as bimanual uterine compression, intrauterine tamponade, uterotonic therapy, administration of tranexamic acid,3) and treatment of DIC, have been used. Along with the spread of interventional radiology (IVR) techniques in the field of obstetrics, hemostatic management using preventive hemostasis and embolization became feasible in the 1990s, leading to a major advancement in the management of uterine hemorrhage.4) Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) proved to be highly effective for achieving hemostasis in obstetrical patients with uterine hemorrhage and hematoma. Therefore, the use of arterial ligation by laparotomy and hysterectomy has markedly decreased. It is not rare that arterial ligation to control massive hemorrhage during cesarean section fails to achieve hemostasis due to an abundance of collateral circulation pathways. Therefore, various new hemostatic procedures such as compression sutures of the uterus,5,6) intrauterine tamponade using gauze or a balloon,6,7) and intraoperative IVR in a hybrid operation room have become available. However, while hemostatic procedures may preserve the uterus, complications such as subsequent endometrial hypoplasia, menstrual disorder, infertility, pregnancy loss, placenta accreta, and uterine rupture have been observed even in cases in which hemostasis with TAE using an absorbable embolus was successful.4,8,9)

Against this backdrop, we reconsidered uterus-preserving hemostatic strategies in obstetrical cases with critical hemorrhage and discuss how to select the optimal strategy based on our current knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of the various hemostatic procedures presently available.

Hemostasis for massive obstetrical hemorrhage, which does not respond to uterotonic agents, was long achieved by employing surgical techniques. Although internal iliac artery ligation has been used for more than a century, its success rate for hemostasis ranged from only 40% to 60.7%. The major reason for this unsatisfactory outcome is that blood flow in the gravid uterus is markedly increased and often has inflow from the external iliac, lumbar, median sacral, and inferior mesenteric arteries via abundant anastomosis of the peripheral internal iliac artery. Therefore, even if the internal iliac artery is ligated, blood flow within the uterine artery may not decrease, potentially rendering successful control of the hemorrhage impossible. In particular, in cases of placenta previa or placenta previa accreta in which the placenta adheres to the lower uterine segment, blood flow from the external iliac artery and other arteries is substantial, further decreasing the effectiveness of internal iliac artery ligation. Consequently, arterial ligation came to be implemented in the vicinity of the uterus. Uterine artery ligation was reported by Waters and colleagues10) in 1952, and ligation of the ascending branch of the uterine artery was reported by O’ Leary11) in 1966. With the aim of enhancing the hemostatic effect, stepwise uterine devascularitzation,12) by which the distal portion of the uterine artery is ligated on the uterine side to block blood flow from the ovarian artery, has been proposed. However, it has become apparent that, although this procedure has a strong hemostatic effect, it is often associated with adverse events, such as necrosis of the preserved uterus and subsequent impaired blood flow, which leads to hypomenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, endometrial hypoplasia, and infertility.13,14) Namely, when blood flows into the uterus from numerous pathways in surrounding areas are blocked in an effort to secure hemostasis, functional disorders of the uterus may occur even if the uterus itself is preserved. In addition, these arterial ligation procedures require laparotomy and are very invasive for patients with massive hemorrhage, especially those in poor general condition. Therefore, arterial ligation is now only rarely implemented since new hemostatic methods including TAE are now widely available.

Uterine hemorrhage often involves a broad surface of the uterine cavity, and therefore, compression techniques applied to the bleeding surface, by means of bimanual compression or uterine packing with gauze as well as the use of drugs to induce uterine contraction, have been the primary methods used to achieve hemostasis. Strong tamponade using gauze or towels has long been performed for uterine hemorrhage after vaginal delivery. However, because it is difficult to completely fill the uterine cavity with gauze so as to leave no space, various hemostatic procedures using balloons have been developed. Pressure hemostasis using a Foley catheter, Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, balloon for the bladder, condom, Fujimetro, etc. have been reported,7) showing the efficacy of these strategies. The Bakri balloon was first reported to be effective for controlling hemorrhage in cases of low-lying placenta, placenta previa, and placenta previa accreta during cesarean section.15) Thereafter, it began to be used for massive hemorrhage after vaginal delivery,16,17,18) and is now approved and widely used as a hemostatic balloon for the uterus in various countries worldwide.

The success rate of balloon hemostasis is 84.0% (77.5–88.8%),14) which is comparable to the average of 84.6% (81.2–87.5%) for arterial ligation. Because balloon tamponade allows monitoring of the amount of bleeding, its hemostatic effect can be assessed within a short period of time as a tamponade test.17) Advantageously, balloon tamponade can be immediately switched to TAE or surgical hemostasis if it does not achieve hemostasis. Recent studies have shown the success rates of hemostasis to be in the range of 86–93.9%; success rates in our clinical experience are also high, at approximately 93.9%.19) A clinical comparison of results obtained before and after the introduction of balloon tamponade revealed a decrease in the frequency of employing surgical hemostatic procedures and TAE in cases of vaginal delivery, indicating the effectiveness of balloon tamponade.17) Currently, balloon tamponade is recommended in the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) and by major academic societies such as the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG), and Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC).14) Even in cases of massive hemorrhage associated with cervical pregnancy in early gestation or ectopic pregnancy in a cesarean section scar, placement of a uterine cervix dilation balloon (Minimetro, Soft Medical Co., Ltd.; Cook double balloon, Tokibo Co., Ltd.), with infusion of a small amount (15–40 ml) of physiological saline, has proven to be effective.19)

However, balloon tamponade can be problematic as the balloon may become dislodged from the uterus, and blindly pressing on the bleeding point may fail to achieve hemostasis. To solve these problems, infusion of water into the balloon while confirming the bleeding point with an ultrasonic contrast agent has been proposed.14) In an effort to prevent the balloon from becoming dislodged, clamping the uterine cervix with forceps, cerclage of the opening of the uterus, and modification of the shape of the balloon have all been performed. The hemostatic effect is known to be reduced in the presence of DIC.

Interventional radiology-assisted control of uterine hemorrhage after vaginal delivery usually relies upon TAE, except for cases in which embolization is not feasible because of uterine rupture or for other reasons. Arterial balloon occlusion by which the balloon at the tip of the arterial catheter is inflated to block the blood flow is used not only for blockage of blood flow in placenta previa accreta but also for control of hemorrhage during gynecological procedures; this has become more widely available due to its safety. In addition, guidelines for the use of IVR in obstetrical hemorrhage cases have been developed and are now widely available.4) On the other hand, accumulation of clinical cases has revealed that various complications such as post-TAE infection, ovarian dysfunction, menstrual disorder, endometrial hypoplasia, infertility, subsequent pregnancy loss, uterine rupture, and massive puerperal hemorrhage occurred even when an absorbable embolus such as a gelatin sponge or porous gelatin powder was used.4,8,9) Therefore, the first-choice procedure for hemostasis is uterine balloon tamponade, and TAE should be used only if balloon tamponade fails. Follow-up contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after internal iliac artery embolization with absorbable gelatin sponge for obstetrical hemorrhage revealed that ischemic areas persisted in the myometrium at 4–8 months after embolization in some cases. It was suggested that these remaining ischemic areas had induced uterine rupture in the subsequent pregnancy.9,20) The decision to employ TAE should not be made without careful deliberation, particularly in patients who wish to have a subsequent pregnancy; TAE should be saved as the last option. The use of TAE to prevent massive hemorrhage prior to treatment for cervical pregnancy, cesarean section scar pregnancy, puerperal pseudoaneurysm, or placental polyp should be avoided whenever possible. TAE should be used not as a means of prevention but as a treatment and emergency care procedure for hemorrhage. When blocking blood flow preventively is the aim, temporary blockage by arterial balloon occlusion is more advantageous in that ischemic damage caused by this method does not persist. Obstetricians need to review carefully and reconsider the position of TAE in hemostatic treatment, its indications, choice of emboli, and degree of embolization to achieve effective hemostasis and prevent dysfunction of the preserved uterus.

When hemorrhage from the placental separation surface was severe, pressure hemostasis with gauze and suture hemostasis were commonly employed but often unsuccessful in cases with bleeding from a large area. Although separation of the bladder may be necessary on the anterior wall, the use of a simple suture or a Z-suture piercing the entire myometrium at several sites, a large U-shaped suture, enclosing sutures21) and an interrupted circular suture22) consisting of repeated simple suturing of the entire circumference of the anterior and posterior walls, have been reported.

On the other hand, Bakri reported that uterine balloon tamponade was effective for the control of bleeding from the separation surface in cases of placenta previa,15) and this method also proved to be effective for achieving hemostasis in cesarean section.6)

2) Compression suturesIn atonic hemorrhage cases, the technique employing compression sutures (B-Lynch technique), which was first reported by B-Lynch et al.23) in 1997, is used when bimanual compression and administration of uterotonics fail to achieve sufficient hemostasis. With this technique, the anterior and posterior walls of the uterus are joined together to compress the bleeding surface. The B-Lynch technique is effective for both hemorrhage from the separation surface in cases with placenta previa accreta and atonic hemorrhage, and for controlling hemorrhage in the lower segment (isthmus) and body of the uterus. Because the B-Lynch technique involves complicated procedures, various modifications (e.g., the Hayman technique, Cho multiple square sutures) have been developed.24) Various hemostatic techniques, such as those involving the uterine body or the lower uterine segment (isthmus) alone or involving both parts of the uterus for atonic hemorrhage, have been reported.5,6,25) Combined use of compression suturing and uterine balloon tamponade has also been reported.14)

When there is hemorrhage in the lower uterine segment on the separation surface in cases with placenta previa, we use our vertical compression suture technique when attempting pressure hemostasis by sewing the anterior and posterior walls at the uterine isthmus together vertically.5,25) The muscular layer in the lower uterus is exposed, and two stitches piercing the anterior and posterior walls, one each on the right and left sides, are placed as vertical ligation sutures. The double vertical compression suture technique is a combination of compression suturing in the uterine isthmus and a modified B-Lynch technique, and is useful for controlling hemorrhage in the uterine isthmus and body, such as that in placenta previa accompanied by DIC or atonic hemorrhage (Figure 1).5,6) In cases of atonic hemorrhage, two vertical sutures alone in the uterine isthmus will suffice (Figure 2). Synthetic absorbable threads such as Vicryl Rapide are used. Various complications have been reported such as uterine infection, uterine necrosis, and Asherman syndrome.24,26,27) As few as two vertical suture stitches can cause pain due to uterine ischemia in a considerable fraction of patients, occasionally requiring laparoscopic removal of the thread.28) This suggests that the vertical compression suturing procedure not only causes hemostasis by pressing the bleeding surface but also blocks blood flowing into the uterus from the right and left sides by means of vertical thread suturing of the uterus.29,30) Therefore, further investigation is necessary to determine whether or not thread removal should be performed even when a rapidly absorbable thread is used.

Double vertical compression sutures.

(Produced with permission from Makino S, et al.: Hemostatic technique during cesarean section. Hypertens Res Pregnancy 2016; 4: 6–10)

(A) Compression sutures at the uterine isthmus are placed to achieve hemostasis for the atonic bleeding or hemorrhage from a placenta previa.

(B) Additional sutures could be placed, as with the modified B-Lynch suture technique, if (A) is not effective.

Vertical compression sutures.

Only uterine isthmus vertical compression sutures would be effective and useful for the uterine atonic bleeding.

IVR techniques for massive hemorrhage during cesarean section include the arterial balloon occlusion technique by which an arterial balloon catheter is inserted preoperatively to prevent massive hemorrhage and the arterial embolization technique is then performed intraoperatively in a hybrid operation room.4,14) The former technique is performed in the context of cesarean section in cases with, e.g., placenta previa accreta, which undergo subsequent hysterectomy. This technique involves preoperative placement of an arterial balloon in, for example, the aorta or common iliac artery, and aims to reduce hemorrhage by inflating the balloon to block arterial blood flow temporarily when a procedure that may induce hemorrhage is used or when hemorrhage occurs.31,32) The latter technique is used for embolization of the bleeding artery in the patient undergoing surgery in a hybrid operating room equipped with a fluoroscopic apparatus, or in the surgical patient who is temporarily transferred to a room where fluoroscopy is available.4) This method is considered to be useful for patients in whom various local hemostatic procedures are ineffective.

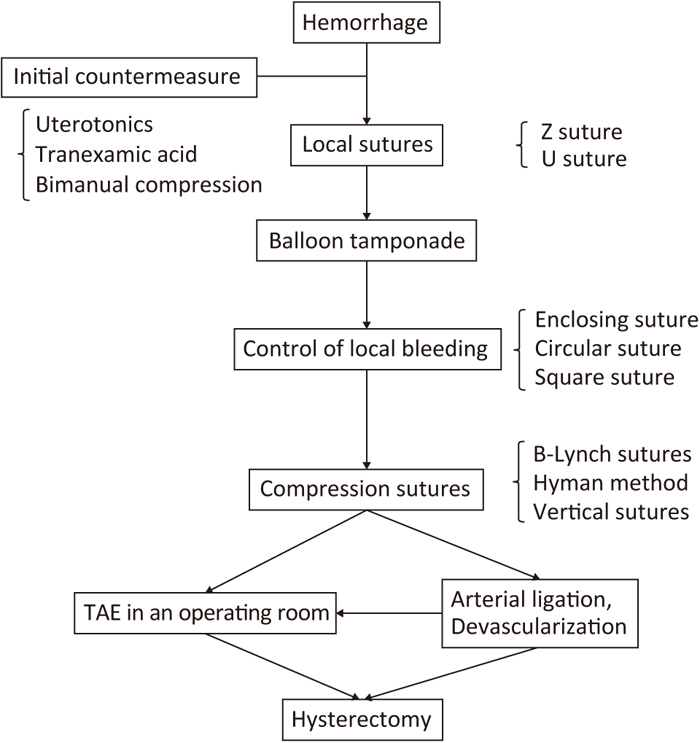

Hemostatic strategies for postpartum massive hemorrhage consist of whole-body management, distinguishing the site of hemorrhage, and prompt local hemostasis. The optimal hemostatic procedure is that which is minimally invasive, allows preservation of the uterus, and has little effect on subsequent pregnancies. Procedures that may affect a subsequent pregnancy, such as TAE and arterial ligation, should be avoided whenever possible. In vaginal delivery cases, hemostasis should be attempted first by balloon tamponade, and if this approach fails to control hemorrhage, then TAE, laparotomic hemostasis, or hysterectomy should be considered (Figure 3). In cases experiencing uterine hemorrhage during cesarean section, it is important to treat the hemorrhage, placing priority on uterus-preserving hemostatic procedures such as direct suturing of the bleeding point, balloon tamponade, and compression sutures (Figure 4).

Hemostatic strategy after vaginal delivery.

Balloon tamponade has priority over TAE

TAE: transcatheter arterial embolization

Hemostatic strategy during cesarean section.

Balloon tamponade or several sutures have priority over TAE or arterial ligation

TAE: transcatheter arterial embolization

Because uterine rupture requires hemostasis by laparotomy, it is important to confirm promptly in transported patients that there is no intraperitoneal hemorrhage or retroperitoneal hematoma on transabdominal ultrasonic tomography. The absence of the retained placenta should also be confirmed. If uterine contractions are poor, bimanual compression and administration of uterotonics should be employed. Tranexamic acid is the drug of choice in patients within 3 h after the onset of hemorrhage.3,33) Fluid therapy, blood transfusion, and antishock therapy should be initiated without delay while paying attention to vital signs. Circulatory maintenance is attempted by rapid administration of colloid solution and albumin solution until a blood transfusion can be administered. In massive hemorrhage cases, red blood cell (RBC) concentrate and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) are administered at a rate of 1:1 to secure a sufficient circulation blood volume. It should be noted that prioritizing administration of RBC concentrate does not improve circulation dynamics, and moreover, may induce hyperpotassemia, resulting in arrhythmias and cardiac arrest. If there is concomitant DIC, local hemostatic measures are ineffective. Therefore, coagulation factors should be supplemented by administration of FFP and fibrinogen preparations to achieve a fibrinogen level of 150 mg/dl or higher.33,34) A platelet concentrate should also be administered if necessary.33)

In critical situations, it is important to perform treatment based on a good understanding of how to deal with atypical compatible blood and blood transfusion in view of the shock index as prescribed in the “Japanese Clinical Practice Guide for Critical Obstetrical Hemorrhage (2017 revision)”.33) When transporting the patient to a higher level medical facility, the following should be implemented: balloon tamponade or gauze filling, compression on the abdominal aorta, reduction of the amount of bleeding to the greatest extent possible, fluid therapy and rapid blood transfusion to maintain circulation dynamics, and warming of the patient. When blood transfusion is not available, albumin and colloid solution should be administered to maintain circulation dynamics. This may induce dilutional coagulopathy and, eventually, prolonged shock and cardiopulmonary arrest that may not otherwise have occurred are more difficult to manage.14)

The greatest cause of intraoperative and postoperative death in patients with severe trauma accompanied by massive hemorrhage is not blood loss from the uncontrollable bleeding source but the lethal triad of death, i.e., metabolic acidosis, hypothermia, and blood clotting disorder.35,36,37) Even when hemorrhage is uncontrollable due to DIC during cesarean section for cases such as those with premature separation of placenta, the first measure to be taken is not immediate implementation of hysterectomy but rather applying pressure with a towel combined with administration of FFP, fibrinogen preparations, and in-house cryo-preparation, attempting to avoid the lethal triad of death. It is not rare that hysterectomy can be avoided by employing these measures. Because the patient’s general condition may worsen during hysterectomy, pressure should be applied with gauze, a towel, or balloon38) after removal of the uterus, and attention should be focused on the treatment of DIC, warming of the patient, and blood transfusion. When the hemorrhagic tendency shows improvement, drain insertion and abdominal closure are performed. If hemostasis is deemed unachievable, the patient is transported to a higher level medical facility after performing temporary abdominal closure or shielding the incision wound by drape, with intra-abdominal packing. In high level medical facilities, patients with critically uncontrollable hemorrhage in shock vital could be treated by intra-aortic balloon occlusion first to control the massive bleeding and to improve hemodynamic shock status. After achieving stable vitals, hemostatic procedures such as surgical sutures or arterial embolization would then be applied.

Implementation of the resuscitation technique while the surgical procedure is halted allows us to avoid unnecessary hysterectomy and hemorrhagic death. In cases of critical obstetrical hemorrhage, as in trauma cases with massive hemorrhage, it is important to first apply pressure on the bleeding point and control hemorrhage (damage control surgery). At the same time, elements of the lethal triad of death should be addressed in order to resuscitate the patient. We believe that a good understanding of the concept and methods of damage control and resuscitation, as well as careful management and transport of the patient based on such knowledge, contributes to the avoidance of both maternal death and hysterectomy.

None.