2021 Volume 21 Issue 2 Pages 85-91

2021 Volume 21 Issue 2 Pages 85-91

Most of the work processes in a pathology laboratory are performed manually by multiple medical technologists; therefore, human error is more likely to occur in examinations performed in pathology laboratories than medical examinations performed in other departments. Thus, our hospital uses “Laboratory Note” as a part of the medical safety management. The information management from this note is operated within the pathological examination system of the Laboratory Information System. So far, reports have emphasized on the importance of incident report and quality management systems in pathological laboratories; however, there have been no research reports on medical safety management using the Laboratory Note.

This study included 527 cases reported in the Laboratory Note from September 2015 to August 2019. These cases were stratified into 30 categories, and a series of examinations were classified into three categories: pre-examination, examination, and post-examination, and the number of reports by year was also tabulated. The most frequently reported category was pathology number management in 53 cases (10.1%). In addition, the number of categories reported during the examination process was the highest at 20 types and 287 cases, followed by 18 types and 166 cases before the examination. Moreover, there was a negative correlation with the number of annual changes and the number of reports.

Records are indispensable for medical safety management in pathological laboratories. The members of the pathology laboratory recorded and shared the various risks and challenges they have experienced during their work in the Laboratory Note. Occasionally, unexpected events can occur daily. The aim of this study was to establish corrective measures to prevent errors from developing into major setbacks.

This paper suggests the importance of risk management in pathological and cytological examinations by risk-assessing the events recorded in this study.

病理検査室の業務は、他部門の臨床検査に比較してヒューマンエラーが生じやすい。当院では医療安全管理(medical safety management)の一環として、「気づきノート」を活用している。ノートの情報管理は臨床検査情報システム(Laboratory Information System:LIS)内の病理検査システムで運用されている。これまでに、インシデントリポートの重要性や品質管理システムの重要性についての報告はあるが、気づきノートを利用した医療安全管理についての研究報告はない。

対象は、2015年9月から2019年8月までに気づきノートに報告された527件である。これらの事象を30種類のカテゴリーに分類し、一連の検査工程を検査前・中・後の3つに分類した。最も多く報告されたカテゴリーは、病理番号管理の53件(10.1%)で、検査中プロセスで報告されたカテゴリーは20種類、287件と最も多く、次は検査前の18種類、166件であった。また、報告数の年次推移件数には負の相関関係があった。

病理検査室の医療安全管理に記録は不可欠で、構成員は業務中に実感した種々のリスクや違和感を「気づきノート」に記録し、この事象を共有する。これらの記録から連携した是正を図り、大きなトラブルに発展することを防ぐのである。このノートは、病理検査室における医療安全管理に有用なツールであると評価した。

Currently, the pathology laboratory of this hospital is operated by the pathology support system in the Laboratory Information System (LIS). Figure 1 shows the route of a sample delivery from receiving an order for pathological or cytological examination to the laboratory. When the receptionist in the pathology laboratory scans the barcode of the submitted request form and the barcode of the sample label with the terminal, a pathology number is issued and the pathology label is printed concurrently. The request form is scanned by the terminal and saved in the LIS as an image file and is not brought into the subsequent work process1), 2). This is to ensure thorough infection control and the prevention of patient information leakage. Pathological specimens are submitted to the pathological examination room from the operating room, endoscopy room, gynecological treatment room, bedside, or each outpatient treatment room, among others. The size of these specimens ranges from small, such as biopsy materials to large, such as parts of the limbs. In addition, as the examination process progresses, the shape of the specimen undergoes various changes as follows: “the original shape of the submitted specimen” to “small tissue piece”→ “tissue cassette”→ “tissue block”→ “tissue section”→ “unstained specimen”→ “stained specimen.” Furthermore, since many of the evaluation processes are performed manually, and a series of processes are taken over by multiple medical technologists, human error is inevitable3)-7).

At our hospital, we devised a “Laboratory Note” intended for daily medical safety management in the pathology laboratory and introduced it into the pathological examination system in September 2015. In this notebook, the challenges (question) and errors (minor trouble) that the technologists encountered are recorded. Risk management using this note is our original approach. So far, there have been reports on numerous incidents and analysis of their contents8), 9); however, there are no research reports on the usefulness of a Laboratory Note for risk management.

The purpose of this paper was to categorize the events reported in the Laboratory Note and to contribute to medical safety through risk management.

1. Objects

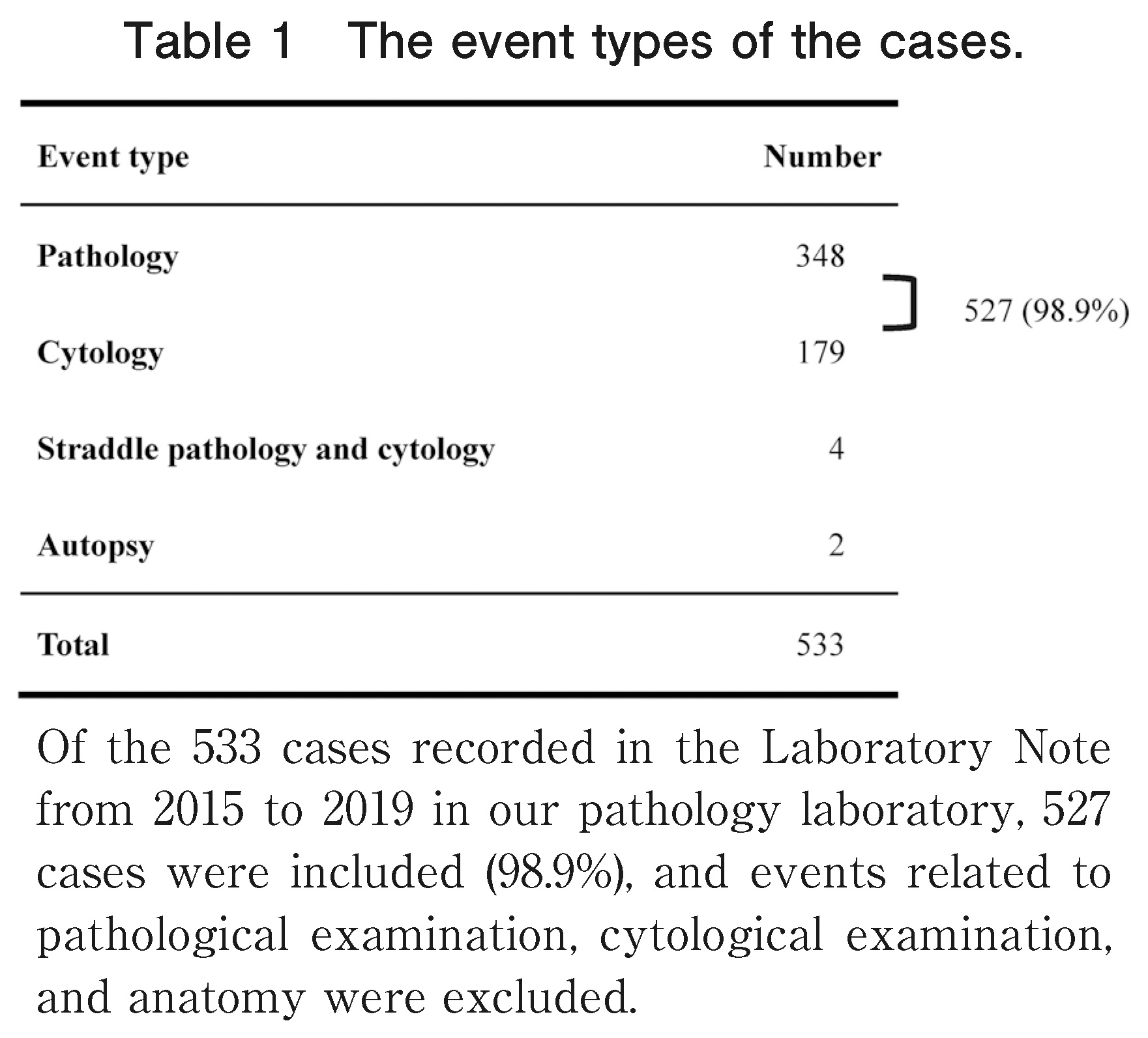

Of the 533 cases recorded in the Laboratory Note from 2015 to 2019 in our pathology laboratory, 527 (98.9%) were included in the study, and events related to pathological examination, cytological examination, and anatomy were excluded (Table 1).

In addition, data on the date and time, report contents, case classification, examination type, examination process, place of occurrence, etc., were recorded in the Laboratory Note.

2. Method

The 527 cases entered in the Laboratory Note were classified into three examination processes as per the international standard ISO 15189 according to the cause of occurrence10), and defined as follows. The pre-examination process was from the collection of the sample to the completion of the acceptance of the sample in the pathology laboratory, and the examination process was to prepare the pathological or cytological sample and submit it to the pathologist or cytotechnologist. The post-examination process was performed after the completion of the sample preparation, such as post-examination result reporting and sample management. In addition, the number of occurrences in each process was calculated, the recorded contents were classified into 30 categories, and the number of occurrences in each category in each examination process was calculated1), 6). Furthermore, the number of reports per year was tabulated.

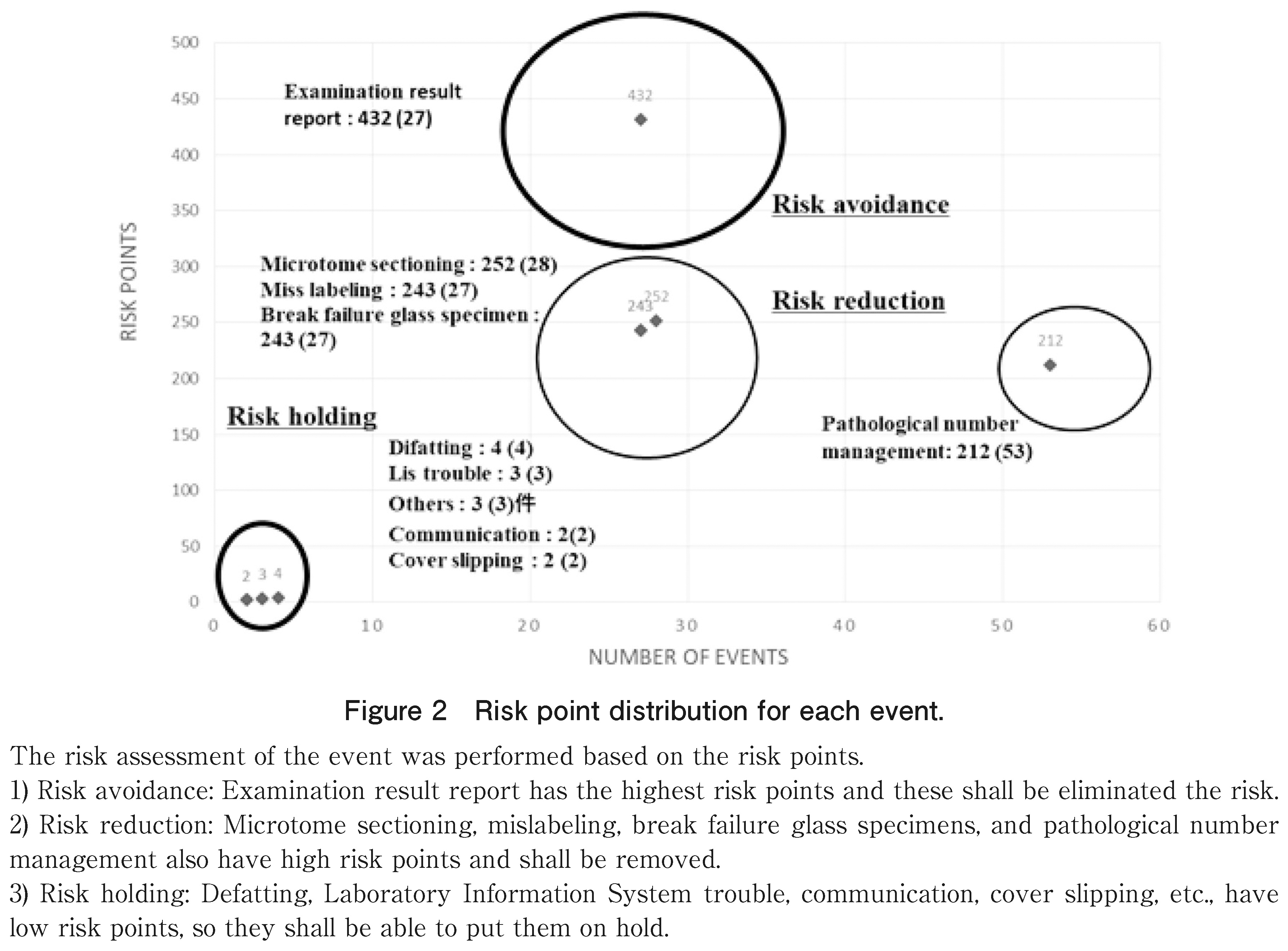

To create a risk assessment table based on these records, the levels of impact on diagnosis in the categories were classified into 1 to 5 (Table 2). Thereafter, the risk points were calculated by multiplying (level numerical value) 2 by the number of cases, and risk evaluation was performed (Figure 2).

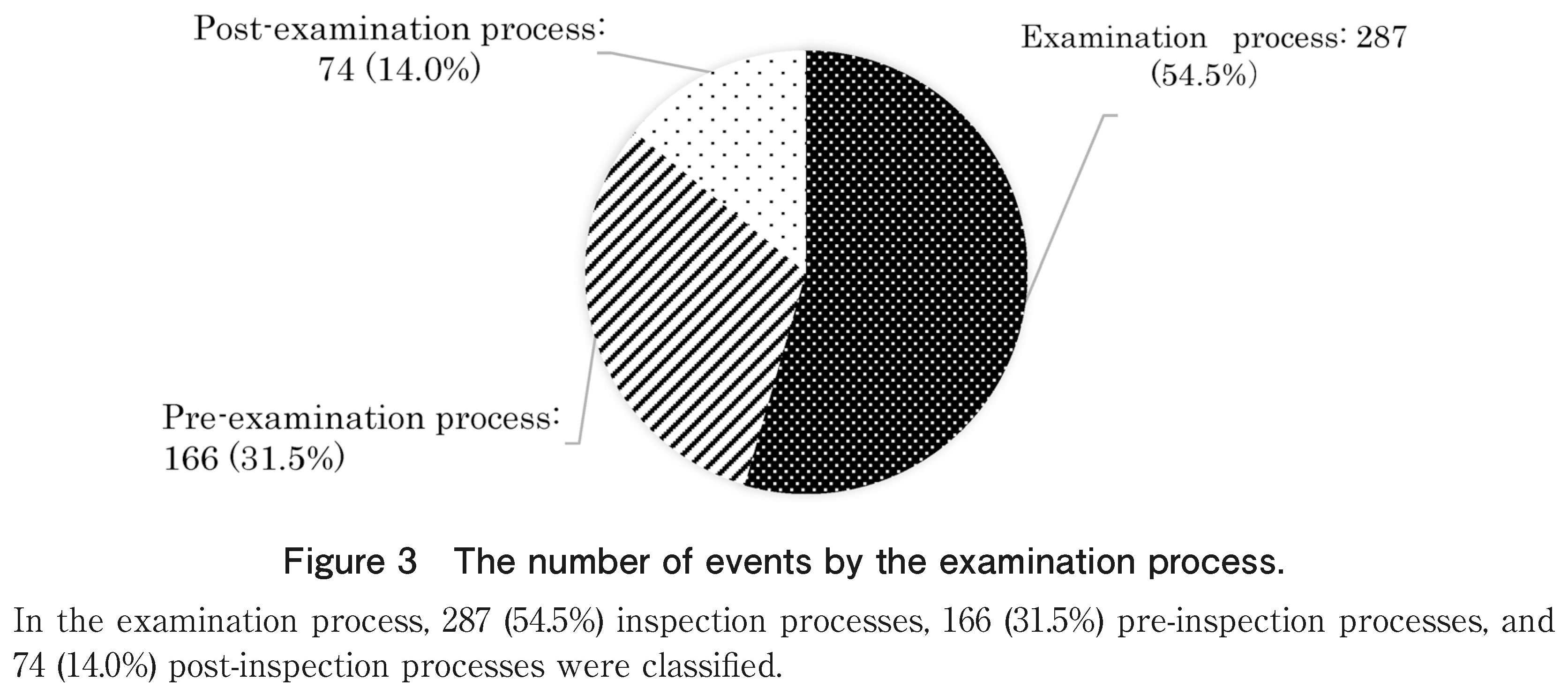

As per the causes of the total number of recorded cases (527 cases) by work process presented in Figure 3, 287 (54.5%) causes of inspection processes, 166 (31.5%) of pre-inspection processes, and 74 (14.0%) of post-inspection processes were classified.

In addition, as shown in Table 2, the most common pathology number management was in 53 cases (10.1%), followed by sample management in 36 cases (6.9%) and equipment management in 36 cases (6.9%). The least common was “others.” which included 1 case (0.2%).

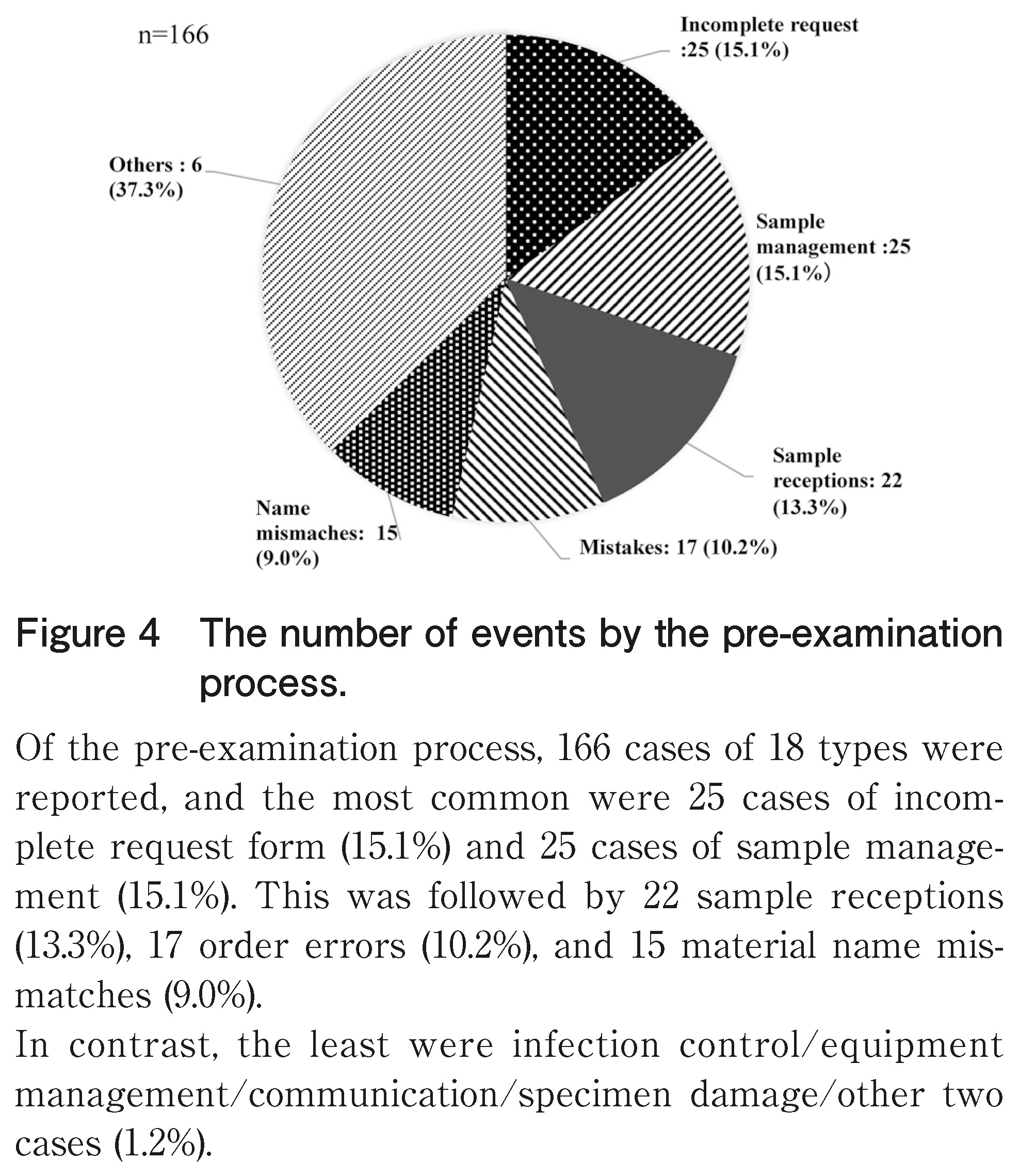

Looking at the number of cases by category in the pre-examination process in Figure 4, 166 cases of 18 types were reported, and the most common were 25 cases of incomplete request form (15.1%) and 25 cases of sample management (15.1%). This was followed by 22 sample receptions (13.3%), 17 order errors (10.2%), and 15 material name mismatches (9.0%).

Conversely, the least were infection control/equipment management/communication/specimen damage/other two cases (1.2%).

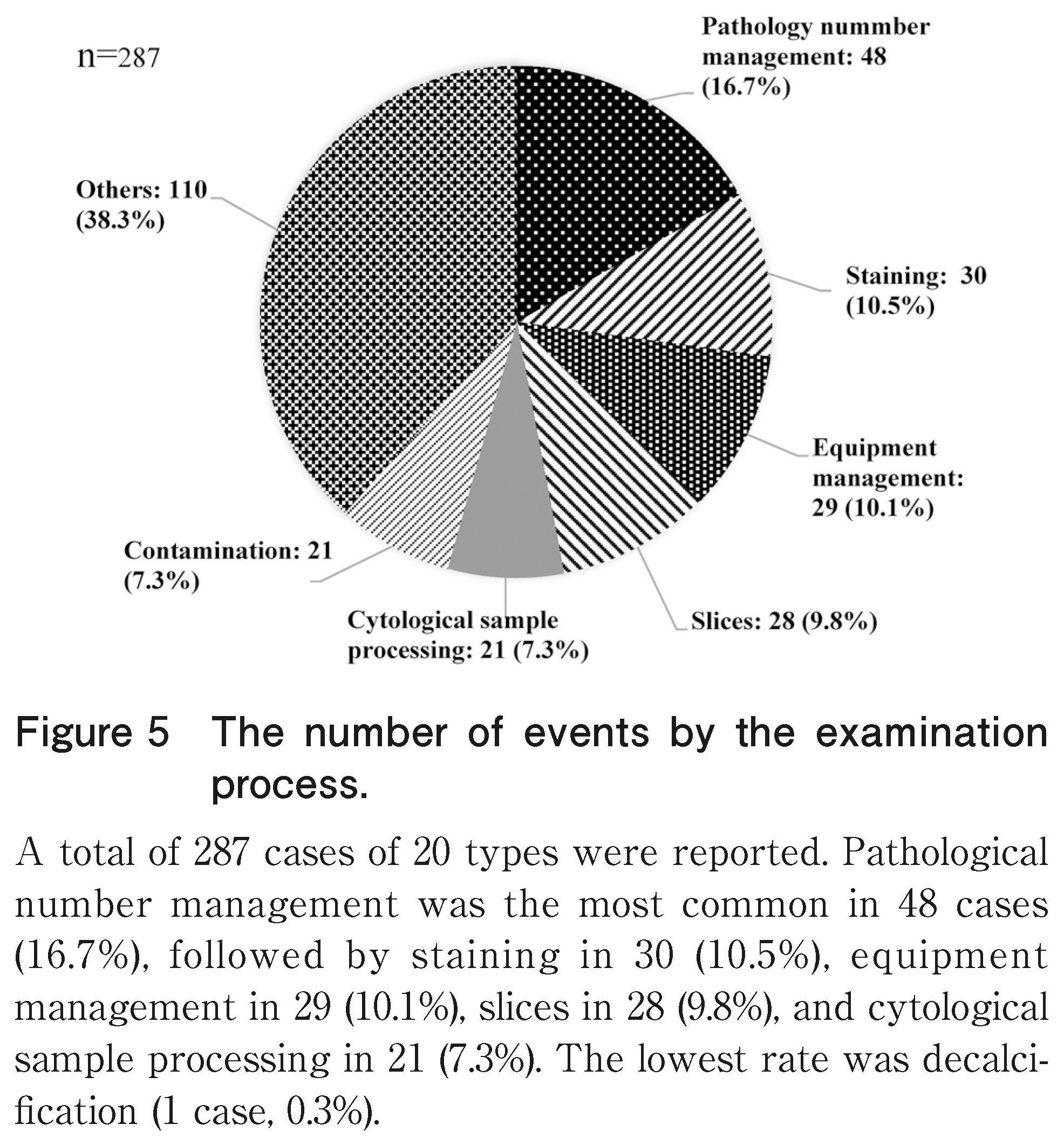

In the examination process shown in Figure 5, 287 cases of 20 types were reported. Pathology number management was the most common in 48 cases (16.7%), followed by staining in 30 cases (10.5%), equipment management in 29 cases (10.1%), slices in 28 cases (9.8%), and cytological sample processing in 21 cases (7.3%). The lowest rate was decalcification (1 case, 0.3%).

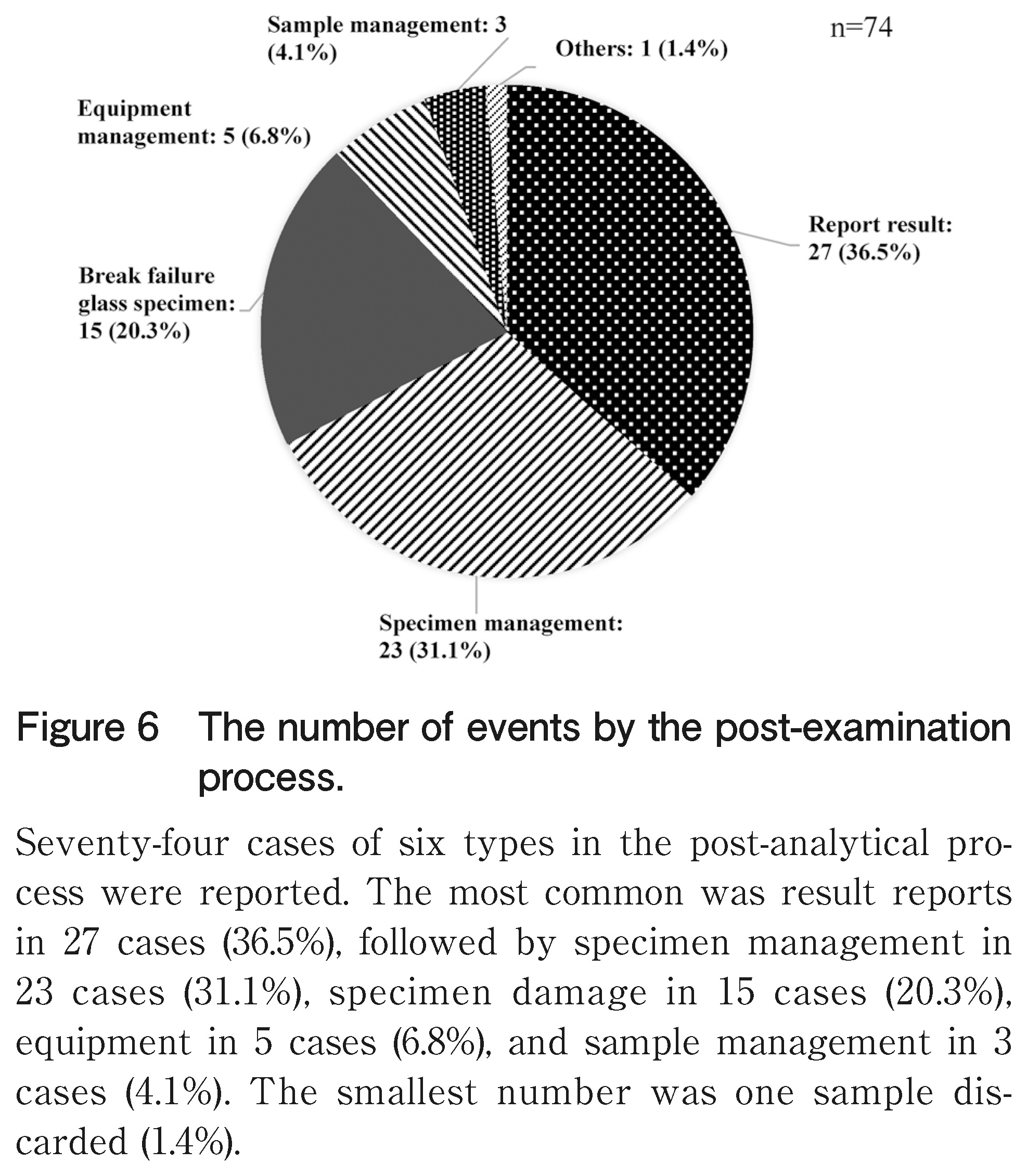

In the post-examination process shown in Figure 6, 74 cases of six types were reported. The most common was result reports in 27 cases (36.5%), followed by specimen management in 23 cases (31.1%), specimen damage in 15 cases (20.3%), equipment in 5 cases (6.8%), and sample management in 3 cases (4.1%).

The smallest number was one sample discarded (1.4%). In addition, the number of annual reports recorded in the Laboratory Note decreased over the years, showing a remarkable decrease of 61.1% in 4 years (Figure 7).

Furthermore, as shown in Table 2, the risk points were the highest in the test results, in the order of thin slices, incorrect labeling, specimen damage, and pathological number management (Figure 2).

The pathological or cytological examination processes with several human errors was divided into three steps, and the causes and countermeasures were considered.

In the pre-examination process, inadequate request forms, sample management, and sample reception were ranked high in the records. These events commence with the reception staff carefully checking the request form, and then they contact the involved individuals and respond to any deficiencies. The reception staff were reminded of the knowledge about specimens, understanding of the pathological examination system, and the need for medical knowledge.

The examination process involves several processes and an enormous amount of work. Therefore, the categorization and numbering of records entail the highest workload. In particular, pathology number management was the most common, and it was also common in the cytological examinations. The pathological examination procedure stated that the number of sections should be entered into the LIS at the time of excision. If there was an input error, the ID/QR code printing of the slide glass at the time of thin cutting would be affected, and the branch number would be incorrect. On the contrary, in cytodiagnosis, errors occurred during transcription of the cytodiagnosis number onto the slide during sample processing. Handwritten transcription was urgently abolished, and automation was recommended.

The medical technologist in charge of the pathological or cytological examination prepares a specimen that is optimal for diagnosis and to thoroughly check the staining status. In addition, regular training among medical technologists is required to ensure specimen suitability. Moreover, cytology sample processing is the most common cytology record. Cytology specimens are liquid, solid, or smeared, among others, and have various shapes, and the number of cells varies significantly depending on the specimen. In such a case, it is probable that numerous events were reported because another work procedure was added. Regarding the processing procedure of the cytological specimens, a manual should be prepared for each specimen and thoroughly disseminated.

In the post-examination process, examination results were the most recorded. Among them, there was a case where a delay in the reporting of the rapid intraoperative diagnosis result occurred due to the absence of the doctor in charge. Furthermore, there was an incident that was corrected immediately after contacting the surgeon by mistake of “negative” and “malignancy” on the intercom. Intraoperative rapid diagnosis is a combination of expeditious specimen preparation by a medical technologist and rapid diagnosis by a pathologist, and the results are reported. A safe and rapid method of reporting results to the surgeon in the pathology laboratory is the most important factor in the risk management in pathological examinations.

In addition, mislabeling in 9 cases before the test, 18 cases during the test, and 10 cases during the cytological examination was reported. These errors were attributed to failure in removing the label during recycling of the sample container leading to mislabeling. There was an urgent need to develop a system that can automatically print cytological glass slides. Favorably, the number of records decreased over 4 years, and the number of incidents was zero.

As shown in Table 2, the impact level classification in pathological examination or cytodiagnosis was performed, the risk points were calculated, and the risk factors were clarified. These were examination result reports, slices, mislabeling, specimen damage, pathology numbers, etc., and these categories are listed as targets for prompt improvement measures. Briefly, risk management that clarifies the risk factors is important.

It was observed that the number of events recorded annually has decreased due to repeated activities that lead to prompt improvement for various events and factors recorded in the Laboratory Note.

The Laboratory Note was able to record minor challenges encountered during daily work other than incidents. It aimed to contribute to daily medical safety management by promptly sharing and reviewing the above information. The events described in the Laboratory Note were examined for each process and were categorized, and the risk points were calculated. A risk assessment was then performed to identify risk factors. Prompt improvement of these risk factors is important. In addition, there were no significant incidents in the pathology laboratory for 4 years of continuous recording.

Through this, it became clear that risk management via the Laboratory Note is linked to medical safety in pathology laboratories.

The authors would like to thank the Field of Safety and Risk Management for Medical Technology, Graduate School, Niigata University of Health and Welfare for discussions on this topic.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.