2025 年 12 巻 p. 309-315

2025 年 12 巻 p. 309-315

Composite or collision tumors in the central nervous system can significantly impact disease progression and metastasis, potentially affecting treatment efficacy. Studying the mechanisms associated with these tumors can provide neuro-oncologists with insights into tumor diversity, progression, and aid in the development of novel treatments. We encountered an 84-year-old female with memory disturbance who presented with tumors consistent with wild-type isocitrate dehydrogenase high-grade glioma and low-grade B-cell lymphoma at the same site. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a solid enhanced mass in the right frontal lobe. A pre-operative suspicion of primary central nervous system lymphoma led to a brain biopsy. Histologically, 2 types of lesions were observed; the first consisted of atypical glial cells with diffuse infiltration and mitoses, positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein and negative for anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) -R132H, characterized by partial amplification of PDGFRA and homozygous deletion of CDKN2A. The second type consisted of small atypical lymphoid positive forCD20, showing immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) rearrangement, and minimal invasion of vessel walls while filling the perivascular space. Based on these findings, collision neoplasms of high-grade gliomas and marginal zone B-cell lymphomas were suspected. To our knowledge, this is the first reported co-existence of a glioma and intracranial lymphoma.

Multiple central nervous system (CNS) tumors are commonly observed in cases of germline disorders, disseminated malignant tumors, intratumor metastasis, or secondary tumors related to chemoradiotherapy. However, composite tumors are relatively rare and typically involve 2 solid tumors. Among CNS tumors, most cases are represented by meningiomas and glioblastomas,1) while the co-existence of a solid tumor and lymphoma is seldom reported. Marginal zone B-cell lymphomas (MZBCLs) of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) -type are non-Hodgkin lymphomas that arise from post-germinal center marginal zone B cells. Due to the challenges in diagnosing primary non-dural CNS MZBCLs, these lymphomas may be overlooked. We present a case of high-grade glioma and MZBCL located at the same site, which was diagnosed as a collision or composite neoplasm.

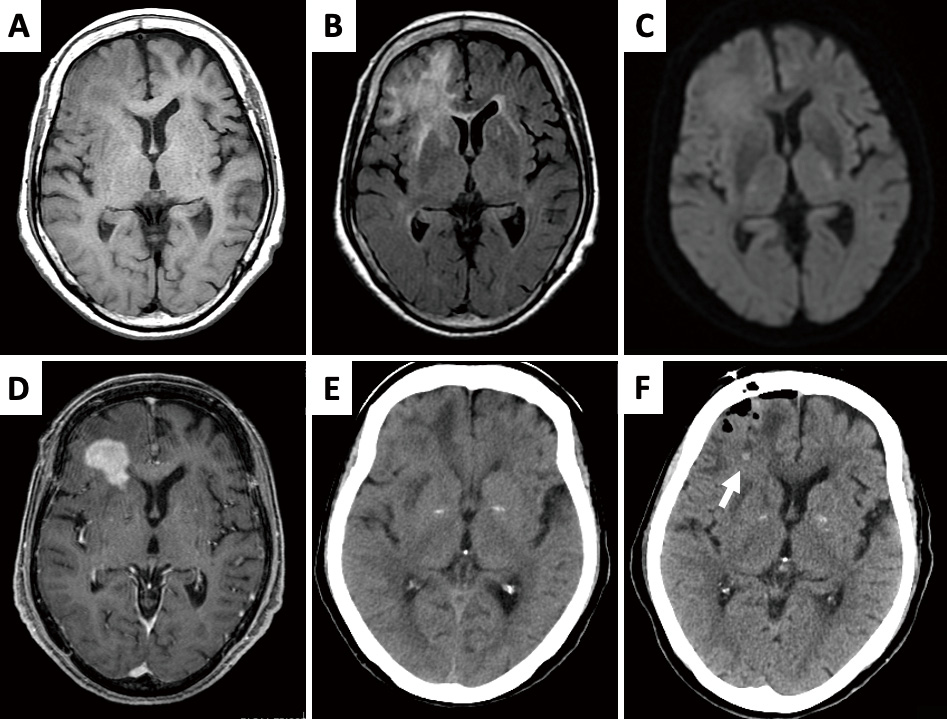

An 84-year-old female presented to our hospital with a gradual, progressive cognitive decline over the past 6 months, without any associated cranial symptoms or paresis. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 15 (E4V5M6). Imaging revealed a tumor in the right frontal lobe, showing slight hypointensity on T1-weighted imaging (Fig. 1A), hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging (Fig. 1B), mild hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (Fig. 1C), and uniform enhancement after gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid administration (Fig. 1D). No other tumorous lesions were detected on full-body scanning. Blood tests showed tumor marker levels of 1.5 ng/mL for carcinoembryonic Antigen and 305 U/mL for soluble interleukin-2 receptor. A suspected diagnosis of primary CNS lymphoma led to a navigation-guided needle brain biopsy, with samples taken from the tumor's center (Fig. 1E, F). The intraoperative diagnosis was high-grade glioma, and the specimen obtained was sufficient for histopathological diagnosis. No new neurological deficits developed post-operatively. Due to the patient's poor general condition and deteriorated consciousness (GCS score of 15, Mini-Mental State Examination score of 27, and Frontal Assessment Battery score of 11), both she and her family opted against further aggressive treatment. Despite concerns about post-operative deterioration, we were unable to monitor her clinical progression, and she passed away 4 months after surgery due to tumor progression. No autopsy was performed. Informed consent was obtained prior to submission, as this case report contains protected health and identification information.

MRI revealed the presence of a tumor in the right frontal robe. (A) The lesion was slightly hypointense on T1WI. (B) Hyperintense on T2WI. (C) Slightly hyperintense on DWI. (D) Uniformly enhanced following administration of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid. (E) Plain CT showed an isodense tumor with edema. (F, arrow) A hemorrhagic point revealing the site of biopsy was identified in post-operative CT.

CT: computed tomography; DWI: diffusion-weighted imaging; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; T1WI: T1-weighted imaging; T2WI: T2-weighted imaging

Following an institutional review board-approved protocol,2) fresh brain tumor tissue was obtained from the patient. Histology was assessed using the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System, 5th Edition criteria.3)

Immunohistochemical analyses were performed as previously described.2) The following antibodies were used for immunostaining, we used the following antibodies: cluster of differentiation (CD) 3 monoclonal antibody (DAKO Cytomation, Kyoto, Japan; 1:50 dilution), CD10 monoclonal antibody (Leica Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan; 1:50), CD20 monoclonal antibody (DAKO Cytomation; 1:5), S-100 polyclonal antibody (DAKO Cytomation; 1:4), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) monoclonal antibody (DAKO Cytomation; 1:12), IDH1-R132H (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, 1:100), Ki-67 monoclonal antibody (DAKO Cytomation; 1:500), and methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) monoclonal antibody (Abcam, 1:1000). Tissue samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and subjected to conventional histological and immunohistochemical treatments. Briefly, 2.5-μm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections were prepared and deparaffinized. For staining, we used an autostainer universal staining system (Roche Diagnostics, BD Bioscience, Agilent Dako). After the reaction, 3,3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride was used for visualization with a ChemMate ENVISION kit/HRP, and counterstaining was performed using hematoxylin.

Two distinct lesions were observed in the same small biopsy specimen. The cerebral hemisphere was found to be diffusely and densely infiltrated with atypical fibrillary or gemistocytic cells containing prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2A-D). In areas with a dense proliferation of astrocytic cells, these cells exhibited nuclear pleomorphism and mitosis (Fig. 2A). Dilated vessels with multilayered endothelial proliferation were also observed (Fig. 2B), though, no typical microvascular proliferation or necrosis was detected. The atypical glial cells were positive for GFAP (Fig. 2C) and S-100, and negative for CD20 (Fig. 2G), CD3, and IDH1-R132H. The Ki-67 labeling index was 10% (Fig. 1D). Follicles of small round cells were observed surrounding the vessels (Fig. 2E-H), with accumulations of small atypical lymphoid cells filling the perivascular spaces, showing minimal invasion of the vessel walls (Fig. 2E). The atypical lymphoid cells were positive for CD20 (Fig. 2G) and negative for CD3, CD10, S-100, IDH1-R132H, and GFAP (Fig. 2C). These cytological findings are indicative of a collision neoplasm of high-grade glioma and low-grade B-cell lymphoma, specifically a MZBCL. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genome was investigated using a method described in previous studies,4,5) and all cells were found to be negative for EBV-encoded small RNA (Fig. 2H). As no autopsy was performed, we were unable to determine the distribution of the glioma and lymphoma within the lesion detected on magnetic resonance imaging.

Two different types of lesions were detected in a biopsy specimen. (A) Atypical fibrillary or gemistocytic cells with prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm were observed to have diffusely and densely infiltrated the cerebral parenchyma. (A) A follicle of small round cells was observed surrounding vessels. (A, inset) Densely proliferating astrocytic cells were characterized by nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses. (B) Also observed were vessels with multilayered endothelial proliferation. (C) Atypical glial cells were established to be positive for GFAP. (G) Atypical glial cells were established to be negative for CD20 (G). (D) For atypical glial cells, a Ki-67 labeling index value of 10% was obtained. (E, F) Small atypical lymphoid cells accumulated within the perivascular space with minimal invasion of the vessels walls. (G) The atypical lymphoid cells were positive for CD20. (C) The atypical lymphoid cells were and negative for GFAP (C). (H) No Epstein-Barr Virus-positive cells were detected.

CD20: cluster of differentiation 20; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein; Ki-67: proliferation marker

Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) samples were obtained using a previously described method.6) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were confirmed by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis. Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (KAPA Express Extract kit; KAPA BIOSYSTEMS, Wilmington, MA, USA). PCR and direct sequencing of H3F3A and the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter (pTERT) were performed as previously described.7,8) No mutations were detected at the C250 and C228 residues of the pTERT or at the K27 and G34 sites of H3F3A (data not shown). The allelic statuses of EGFR, PDGFRA, and CDKN2A were assessed using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) with a SALSA MLPA kit P105 (HRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). PDGFRA amplification and CDKN2A homozygous deletion were identified (Fig. 3A), the latter consistent with the loss of MTAP expression (Fig. 3B). Amplification of immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) from the framework 2 sequence of the variable (VH) segment to the joining (JH) region was performed using consensus primers complementary to the framework 2 portion from genomic DNA. Amplification of IgH from the framework 2 sequence of the V segment to the J region was performed using consensus primers complementary to the framework 2 portion of the VH region (FR2B) and the JH region (CFW1) from genomic DNA.6)IgH monoclonality of the rearrangement was also detected (Fig. 3C).

(A) The atypical glial component was characterized by partial amplification of PDGFRA and homozygous deletion of CDKN2A, as determined by MLPA. (B) We also demonstrated the loss of cytoplasmic MTAP expression in astrocytic tumor cells. (B, arrow heads) whereas endothelial cells, as internal controls, showed weak positivity. (C) In addition, monoclonal patterns of IgH rearrangement were detected using polymerase chain reactions.

CDKN2A: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2a; IgH: immunoglobulin heavy chain; MLPA: multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification; MTAP: methylthioadenosine phosphorylase; PDGFRA: platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha

In this case study, we report the occurrence of a dual tumor consisting with an IDH wild-type high-grade glioma component and a low-grade B-cell lymphoma component at the same site. Since no other tumors were detected throughout the body, we concluded that these tumors were double primaries. The atypical glial component in this case demonstrated high proliferation potential and abnormalities in PDGFRA and CDKN2A, consistent with a high-grade glioma, comparable to a glioblastoma, rather than reactive astrocytosis. Based on our clinical, morphological, and genetic findings, we diagnosed the growth as a collision tumor of high-grade glioma, not otherwise specified, and MZBCLs of MALT type. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the co-existence of a glioma and intracranial lymphoma.

The co-existence of solid tumors and lymphomas is rare, with most synchronous tumors being identified in the gastrointestinal tract. Diffuse large B-cell (DLBCL) and MZBCL are the most common types of lymphoma to collide with solid neoplasms.9) In intracranial lesions, cases of DLBCL or T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma have been reported alongside hemangiomas and pituitary neuroendocrine tumors,10-12) with the majority of co-existing tumors involving meningiomas or hemangiomas. Additionally, tumor-to-tumor metastasis has been observed, as recipient tumors tend to be slow-growing have a rich blood supply.1,13,14) Collision tumors involving high-grade gliomas and other tumors are rarely reported, with meningiomas being the most common co-existing tumor.15)

Collision tumors represent a distinct category of multiple tumors, defined as 2 distinct tumors that are in contact with or partially invade each other. Distinguishing collision tumors from tumor-to-tumor metastases or from the heterogeneity of the same tumor can be challenging for pathologists. Although tumors with different histomorphologies and genomic features may have different origins,16) the tumorigenesis of collision tumors has yet to be thoroughly understood. It is of particular interest to determine whether the 2 neoplasms in such cases arise independently, coincidentally, or share common triggering factors. It is conceivable that 1 type of tumor may contribute to the development of the other, or that both tumors may have a shared cancer stem cell origin. Additionally, the local immune response of existing tumors may influence the tumorigenesis of another. Patients with chronic gastric inflammatory diseases or conditions are known to have an increased risk of both epithelial tumors and lymphomas,17) as the microenvironment can trigger genetic and/or epigenetic alterations that lead to tumorigenesis. Furthermore, it has been established that secondary chronic inflammatory processes induced by solid neoplasms can trigger lymphomas.9) Another hypothesis suggests that a single progenitor cell may give rise to multiple different types of tumor cells.18) However, the origin of glioma stem cells remains undetermined. Previous reports have indicated that the progenitor-like cells of glioblastomas comprise various constituents and are characterized by plasticity in the mesenchymal cell medium. Moreover, genetic events can influence the direction of tumor differentiation,19) and gliomas and lymphomas are known to harbor distinct genetic alterations. Consequently, detailed genetic investigations could significantly contribute to understanding the pathogenesis of collision cancers.20)

MZBCLs are non-Hodgkin lymphomas that originate from post-germinal center marginal zone B cells. Systemic MZBCLs are divided into 3 types: extranodal MZBCLs of the MALT type, nodal MZBCLs, and splenic MZBCLs. Histologically, intracranial MZBCLs correspond to systemic extranodal MZBCLs of the MALT type, characterized by perivascular expansive monotonous proliferations of small atypical B lymphoid cells with plasma cell differentiation, minimal invasion from the perivascular space, and the absence of vascular changes. Notably, the pathological diagnosis of primary nondural CNS MZBCLs of the MALT type is challenging, as the specimen size may be insufficient for flow cytometry or genetic analysis. However, PCR analysis of IgH rearrangements has proven useful in distinguishing between acute demyelinating disorders and B-cell neoplasms.21) All MZBCL cases we have previously reported exhibited IgH clonal rearrangements,6) and nearly all patients had an indolent clinical course. Additionally, while systemic MZBCLs have been linked to chronic inflammation, infection, or autoimmune disease,22) there is currently no consensus regarding the origin of intracranial tumors.

Despite the identification of numerous genetic and epigenetic variants, the etiology of high-grade gliomas remains unclear. However, the incidence of glioblastoma, the most common type of high-grade glioma, is rising in Western countries.23) In mice, systemic inflammation has been associated with malignant gliomas,24) whereas a history of allergies has been linked to a reduced risk of glioblastoma.25) These findings suggest an association between environmental factors and tumor development. Moreover, co-existing cases of glioblastoma and meningioma have been found to share similar expression pattens of growth factors and signaling molecules, raising the possibility that 1 tumor may induce or stimulate the other.26)

ConclusionIn summary, we report a rare case of the co-existence of a primary diffuse high-grade glioma and low-grade B-cell lymphoma, which were morphologically, molecularly, and genetically characterized. Further studies are needed to elucidate the tumorigenesis of collision tumors.

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP23K14490).

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

The protocol of the research described herein was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kurume University (Number 23063), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

All authors have no conflict of interest.