2015 年 2 巻 4 号 p. 140-142

2015 年 2 巻 4 号 p. 140-142

The diagnosis of peroneal nerve (PN) entrapment neuropathy (PNEN) is based on clinical symptoms and nerve conduction studies. However, these studies do not always detect PNEN. Our 64-year-old patient suffered persistent left L5 numbness after two lumbar surgeries. Two years before admission to our institute his left leg pain gradually reappeared. When walking, his numbness in the left lower thigh to the dorsum of the foot increased. Electrophysiological testing revealed no conduction block on the PN. To identify the origin of his intermittent symptoms we performed loading of repetitive ankle plantar flexion in the at-rest posture to avoid the lumbar factor. We used this provocation test to check for PNEN because it occurs at a site where the PN passes the soleus- and the peroneus longus muscle (SM, PLM). The symptoms appeared reproducibly within 10 s of loading. PN neurolysis under local anesthesia showed that the PN was strongly compressed by the SM and PLM. This procedure eased his symptoms and he was able to walk without elicitation of numbness and pain upon repetitive ankle plantar flexion. In our case, repetitive plantar flexion elicited the symptoms and this provocation test may be useful to identify PN dynamic entrapment neuropathy as the origin of intermittent claudication.

Peroneal nerve (PN) entrapment neuropathy (PNEN) is a known cause of numbness and pain in the lateral lower thigh and dorsum of the foot, and of foot drop due to paralysis of the affected muscles. Surgical decompression of the common PN around the fibular head produces symptom abatement.1–4) As the diagnosis of PNEN can be difficult, it tends to be misdiagnosed as lumbar spine disorder. We encountered a patient with intermittent claudication due to PNEN whose symptoms were improved by PN neurolysis.

A 64-year-old male with diabetes mellitus had a history of abdominal surgeries due to gallstones and appendicitis. There was no identifiable cause of his PN palsy such as orthopedic procedures or leg trauma. Seven years earlier he suffered left leg- and low back pain for which he underwent two lumbar posterior decompression procedures at a local hospital. His lower limb pain decreased, however, numbness in the left L5 area persisted. Two years before admission to our hospital his left leg pain gradually reappeared. He was conservatively but unsuccessfully treated elsewhere with medications including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and later he came to our hospital.

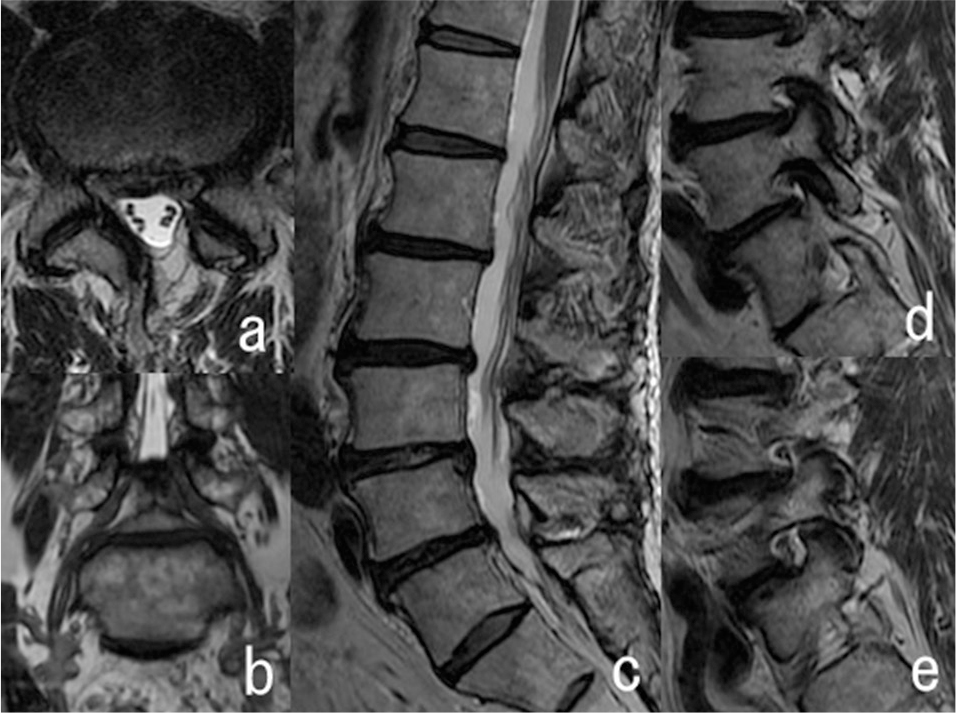

On admission, he reported numbness from the left lower thigh to the dorsum of the foot at rest. Walking exacerbated the symptoms and elicited pain in that area. He was unable to walk more than 100 m and experienced intermittent claudication. There was slight motor weakness of the ankle dorsiflexor at rest; it was gradually increased by walking and he stumbled easily. The Tinel sign test over the PN was not informative and lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study showed adequate decompression of the left L5 root (Fig. 1). The clinical symptoms led us to suspect PNEN despite the absence of an identifiable cause at onset or of an obvious inciting event.

Lumbar T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. The axial image of L4/L5 (a) shows adequate decompression of the L5 root on the spinal canal. Coronal- (b) and sagittal (c–e) images show no left L5/S1 foraminal stenosis.

We performed electrophysiological testing to measure the motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV) of the PN. Stimulation applied proximal (head of the fibula) and distal (ankle) to the entrapment point elicited responses at the extensor digitorum brevis muscle. The MNCV proximal and distal to the entrapment point was 51.2 m/s, indicating that there was no conduction block on the PN in the at-rest position. He did not undergo electromyogram (EMG) or sensory nerve conduction (SNC) studies.

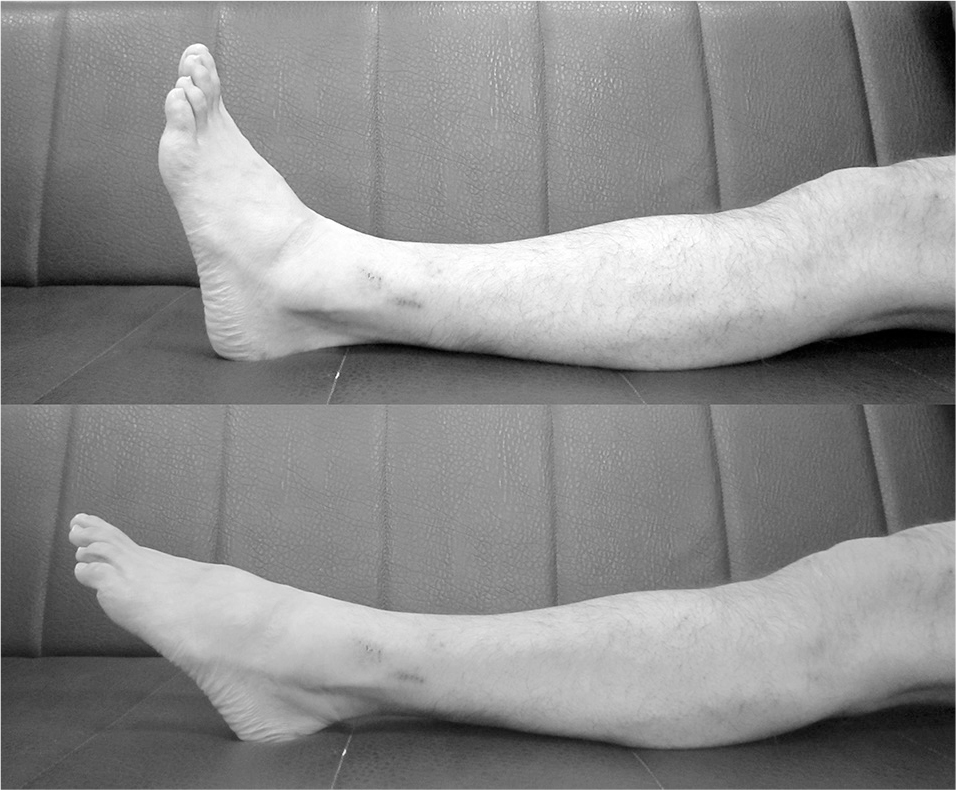

His symptoms failed to improve under observation therapy and their severity affected his activities of daily living. To identify the origin of the intermittent symptoms we observed his ankle plantar flexion during walking. As a PNEN provocation test we also performed loading of the repetitive ankle plantar flexion in the at-rest position to avoid the lumbar factor (Fig. 2). His symptoms appeared reproducibly within 10 s of loading.

Sample picture of the repetitive ankle plantar flexion test.

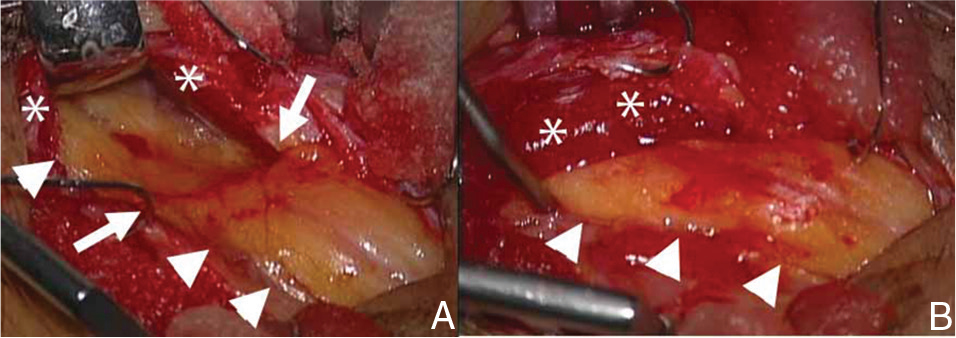

Using a microscope and no proximal tourniquet, we performed left PN neurolysis under local anesthesia.5) We made a 3-cm oblique skin incision behind the fibular head and proceeded antero-inferiorly along the PN. This revealed the PN behind the fibular head. As the PN was strongly compressed by the fibrous band between the superficial head of the PLM and the SM, we dissected it distal to the peroneal tunnel. The PN was also strongly compressed by the PLM and we dissected its fascia and decompressed the PN distally due to retraction of the PLM (Fig. 3).

Photographs showing the surgical field of the peroneal nerve (arrowhead) and the site of entrapment (arrow) by the peroneus longus muscle (**). A: The peroneal nerve (arrowheads) is strongly compressed by the peroneus longus muscle and fascia (*). Note the impression (arrows). B: Photograph taken after decompression of the peroneal nerve (arrowheads).

His postoperative course was uneventful. The procedure produced symptom relief and the patient was able to walk and perform repetitive ankle plantar flexion without the elicitation of numbness or pain.

PN neuropathy is the most common peripheral neuropathy of the lower extremities and the most frequent cause of numbness and pain in the lower limbs.1–3,6) As PNEN cannot be diagnosed radiologically, its diagnosis requires the evaluation of clinical symptoms and nerve conduction studies.3) Maalla et al.2) reported that in their PN decompression surgery series, half of their patients suffered only isolated sensory dysfunction while others manifested both sensory and motor dysfunction. The Tinel sign over the fibular head suggests PN compression and may warrant PN decompression surgery.1) In some instances, compression of the L5 nerve root is concomitantly present; this may mimic PN entrapment at the fibular tunnel because there is considerable overlap between the muscles and the sensory areas served by these two nerves.2) Our patient had a history of two lumbar surgeries with L5 root numbness as a sequela.

Others reported that electrophysiological findings were useful for the diagnosis of PNEN and the identification of the neck of the fibula as the site of nerve compression2,3,7) although Maalla et al.2) acknowledged that electrophysiological studies did not always detect PNEN anomalies; sensory potential amplitudes were decreased in 12- and motor conduction velocities in 7 of their 15 PNEN patients. Our patient suffered intermittent claudication and was unable to walk more than 100 m due to pain in the area of the PN. At rest, his symptoms were not severe. Although we did not perform EMG and SNC studies, this may explain why the at-rest electrophysiological findings were normal. We suggest that the provocation test we used may be as useful for the diagnosis of PNEN as the Phalen test is, for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.8)

The PN is entrapped around the fibular tunnel and then passes the PLM.3) During surgery, the PN is compressed by the fibrous band between the superior head of the PLM and the SM and by the PLM per se. Decompression in this area is important during PNEN surgery.5) The SM carries out plantar flexion of the ankle and the PLM is involved in plantar flexion and extortion of the ankle; the PLM is primarily involved in plantar flexion while the peroneus brevis muscle is primarily involved in ankle extortion. We speculated that repetitive plantar flexion would result in loading the PN without lumbar loading. During the provocation test, the symptoms in our patient appeared within 10 s of loading and he was not able to continue for more than 60 s because of increasing numbness and pain. Based on these observations, we diagnosed PNEN around the fibular neck and performed successful neurolysis of the PN. In our case, the provocation test we used helped to detect PN dynamic entrapment neuropathy as the source of intermittent claudication.

The causes of PN palsy are multiple, previous orthopedic procedures and leg trauma were reminded. In 0–67% of operated PTEN patients no identifiable cause of their PN neuropathy could be found.1–4) Similarly, the cause of PNEN in our patient was unknown although it produced severe intermittent claudication. Based on our observations, we suggest that in the absence of an obvious inciting event eliciting PN dysfunction, PNEN should be considered in patients with intermittent claudication.

Morimoto et al.5) reported that intermittent claudication may occur due to PNEN although at-rest electrophysiological findings are normal. While the repetitive plantar flexion test may help in the detection of dynamic PNEN, the PN and its branches can be entrapped not only around the fibular head but also in the dorsum of the ankle. Although ankle movement may affect the distal portion of the deep PN, the entrapment point, the area involved by the symptom and positive for the Tinel sign, provides information on the affected nerve and the entrapment point.1) We did not perform electrophysiological testing although such studies could have yielded detailed information about PN dynamic entrapment neuropathy. Prospective studies are underway in our laboratory to determine whether the provocation test we used reliably identifies PNEN and whether there is a correlation between the test results and electrophysiological findings. We are also investigating whether PNEN may be a differential diagnosis in patients with intermittent, otherwise inexplicable claudication.

We report a patient with intermittent claudication due to PNEN. Repetitive plantar flexion elicited symptoms, and the provocation test we used helped to identify PN dynamic entrapment neuropathy as the origin of his intermittent claudication. Prospective studies using our provocation test are underway to assess its usefulness for the identification of PN dynamic entrapment neuropathy.