2021 年 8 巻 1 号 p. 811-816

2021 年 8 巻 1 号 p. 811-816

A 78-year-old man, who had undergone lumboperitoneal shunt (LPS) placement for idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus eight years prior, presented with intermittent claudication, lower back pain, and radicular pain on the inside of the right thigh. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an extradural arachnoid cyst (EDAC) above the lumbar catheter of the LPS. The EDAC compressed the spinal dural sac and cauda equina toward the anterior side at level L3/4, triggering his clinical manifestations. The LPS was removed and simultaneously converted into a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS), which immediately improved the neurological deficits. Postoperative MRI showed shrinkage of the cyst and restoration of the compressed cauda equina. Spinal EDAC is a rare entity resulting from arachnoid membrane herniation due to a small defect in the dura mater. This is the first report showing that symptomatic EDAC can be accompanied by the lumbar catheter of the LPS and that a mere conversion from LPS to VPS or ventriculoatrial shunt might be sufficient to shrink LPS-related EDAC without invasive lumbar surgeries.

Lumboperitoneal shunt (LPS) is used to manage idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH), and its safety and effectiveness have been widely accepted.1–4) Among the LPS-associated complications, radicular pain, which is mainly caused by a conflict between the spinal nerve root and excessive length of the lumbar catheter, has been recognized as a rare (comprising less than 5%) but important complication.5–7) Here, we describe a case of cauda equina syndrome, a rare complication of LPS, induced by an extradural arachnoid cyst (EDAC).

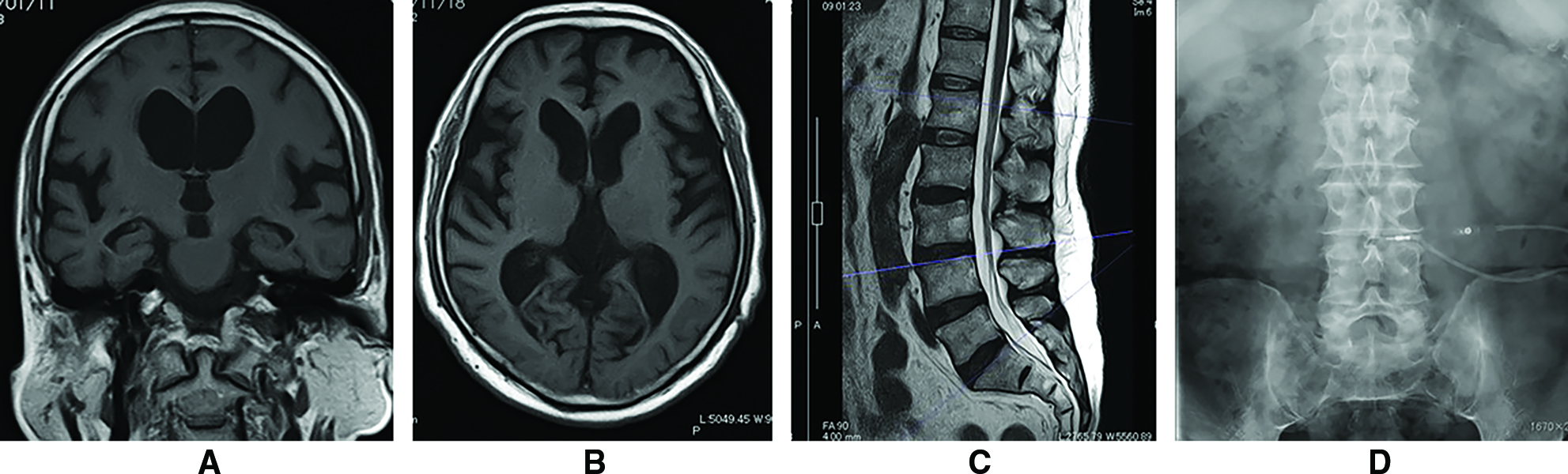

A 70-year-old man, taking daily aspirin and antihypertensive drugs, with a medical history of myocardial infarction, was referred to our hospital for mild progressive gait disturbance. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed the typical appearance of disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid-space hydrocephalus (DESH), with an Evans’ index of 0.34, compatible with probable iNPH8–10) (Fig. 1A and 1B). The lumbar spine did not show any abnormalities at that time (Fig. 1C). The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tap test improved his gait, indicating a positive response to CSF diversion surgery. The patient underwent surgical intervention, in which LPS was implanted using a Codman-Hakim programmable valve with a siphon guard system (Itegra LifeSciences, Princeton, NJ, USA) (Fig. 1D).

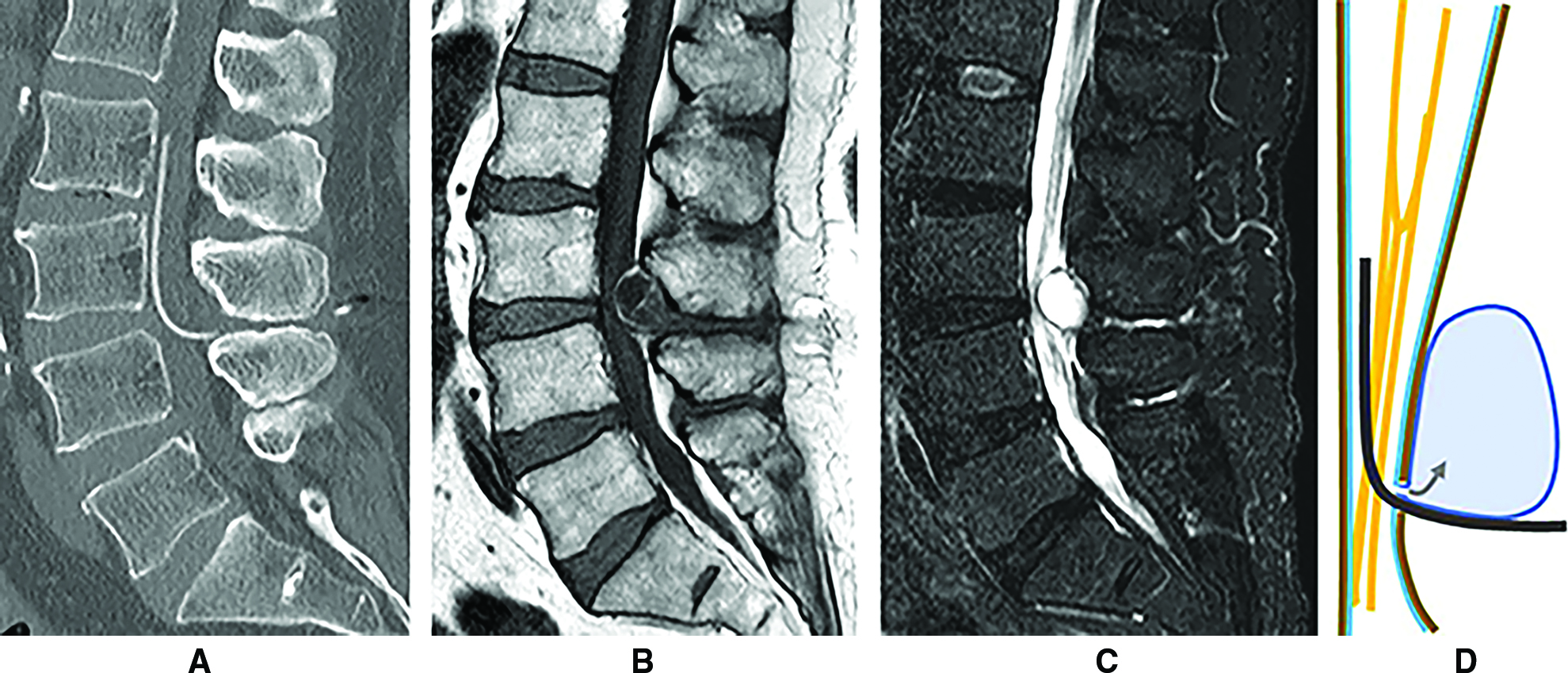

His postoperative course had been uneventful until 8 years after LPS implantation, when he complained of difficulty walking caused by pain around the lower back and right thigh, without motor weakness of the lower extremities, pathological reflexes, or urinary dysfunction. Computed tomography (CT) revealed that the lumbar catheter of the LPS ran through the spinal canal, without snaking from the L3/4 to the L2 level (Fig. 2A). Conversely, MRI indicated the presence of an extradural fluid-containing mass compressing the spinal dural sac toward the anterior side at the L3/4 level (Fig. 2B and 2C). This mass appeared to be on the lumbar catheter (Fig. 2D) and was consistent with an EDAC indirectly compressing the cauda equina. As a first step in the management of cauda equina syndrome, LPS was withdrawn and a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) was simultaneously implanted to prepare for further interventions against EDAC. Subsequently, the radicular pain and intermittent claudication weakened gradually and diminished within a week after the intervention, without any additional invasive surgeries for the lumbar spine. Postoperative MRI after a month demonstrated shrinkage of the cyst, and restoration of the cauda equina that was compressed from the outside of the dural sac (Fig. 3A and 3B).

LPS has the advantage of complete extracranial surgical management and can minimize intracranial complications. Although some previous studies have reported a relatively high revision rate for LPS (>30%), particularly when applied to high-pressure hydrocephalus,6,11,12) some recent reports found an acceptable rate of approximately 10% when applied selectively to iNPH patients.2,3) Complications associated with lumbar catheters, which are summarized in Table 1, are rare compared to other complications related to shunt valves and peritoneal catheters. Radicular pain associated with lumbar catheters of LPS is explained by compression of the nerve roots by excessive length of the lumbar catheter coiling or tangling in the spinal canal,13) and revision surgery is sometimes required.5,7,11) In the present case, the fluid-containing mass at the L3/4 level indirectly compressed the cauda equina, resulting in obscure radicular pain.14,15) Another unusual complication associated with lumbar LPS catheter is intracranial hypotension resulting from CSF leakage through an enlarged defect in the lumbar dura made by the catheter16–18) or from the side holes of the nearly pulled-out lumbar catheter.19) In the present case, the arachnoid membrane with the accompanying CSF might have protruded from the dural defect created by the lumbar catheter and expanded into the extradural space eight years after the LPS was implanted.

| Type of complications | Cause | Treatment option | Frequency (cases) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiculopathy/myelopathy | EDAC | SR (LPS->VPS) | (1) | Present case |

| Nerve root compression | SR > CO | 2–5% | 2, 5, 7, 11 | |

| Spinal cord compression | SR | <0.5% | 5, 13 | |

| CSF leakage | Dural defect around the catheter | EBP, CO | (3) | 16, 17, 18 |

| Side holes of the migrated catheter | SR | (1) | 19 | |

| Catheter occlusion | Epiarachnoid placement | SR | <2% | 2 |

| Prolapse, migration | SR | <10% | 3, 11 | |

| Fracture | SR | <10% | 7 | |

| Intradural neurenteric cyst | SR | (1) | 22 |

CO: conservative observation, CSF: cerebrospinal fluid, EBP: epidural blood patch, EDAC: extradural arachnoid cyst, LPS: lumboperitoneal shunt, SR: surgical revision, VPS: ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

Since the surgical specimen of the cyst wall was not available in our case, the fluid-containing mass was diagnosed as EDAS on the basis of circumstantial evidence that the cyst content was compatible with CSF according to the pre- and postoperative MRI. Epidermoid cyst (EC) is one of the most considerable differential diagnoses in this case because it is well known as a late complication of lumbar puncture.20) Diffusion-weighted MRI can effectively distinguish between them; however, the image was not available in this case. Instead, EC, which is mainly composed of keratin and lipid-rich debris, cannot be shrunk by mere withdrawal of the lumbar catheter. Synovial and ganglion cysts could also be eliminated from differential diagnosis because they are usually associated with osteoarthritis,21) which was not observed in the present case. Extradural abscess, sometimes displaying the same findings on MRI as CSF, can also be ruled out by the lack of an episode of infection or inflammation in the perioperative period. These cystic lesions have never been reported in association with the lumbar catheter of LPS. An intradural neurenteric cyst surrounding the lumbar LPS catheter has been reported in a patient with pseudotumor cerebri, which was caused by the retrograde migration of enterogenous cells through the LPS catheter without a one-way pressure valve.22) To the best of our knowledge, a new development of an arachnoid cyst associated with the proximal catheter of a CSF shunt has never been reported, while the literature describes a case of expansion of a pre-existing intracranial arachnoid cyst caused by a cystoperitoneal shunt malfunction.23)

EDACs, mostly found in the thoracic spine, are an unusual but noteworthy cause of radiculopathy and/or myelopathy, accounting for 1–3% of spinal tumors (Table 2).24–26) Although most EDACs have been supposed to have congenital or idiopathic origin,27,28) several case reports have described traumatic or iatrogenic events years prior to the development of EDACs as a certain cause of these cysts.29–31) The arachnoid membrane may prolapse gradually through the spinal dural defect due to physical reasons and expand into the extradural space. It has been postulated that a ball-valve mechanism in the communicating pedicle between the intradural CSF and the cyst may lead to the accumulation of CSF into the EDAC.32) In our case, we speculate that the pulsatile friction of the silicon catheter, as well as the intermittent intraspinal pressure change generated by the shunt valve and the anti-siphon device, might have spread the dural hole for years, consequently resulting in protrusion and expansion of the EDAC.

| Epidemiological features | General information | Present case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 1–3% of spinal tumors | – | 24, 28, 33, 34 |

| Localization | Thoracic (65%) > lumbar (25%) > sacral (7%) > cervical (3%) (occasionally multiple segments) | Lumbar | 24, 26–28, 33, 34 |

| Age | Adolescent (thoracic) > middle aged (lumbar) | 78 years | 24, 27, 28, 33, 34 |

| Sex | Male > female | Male | 24, 28, 33, 34 |

| Etiology | Unknown (idiopathic, congenital) > secondary to trauma, inflammation, and infection | Lumbar catheter | 24, 27, 28, 33, 34 |

| Clinical presentation | Radiculopathy or/and myelopathy (depending on localization) | Radicular pain | 24, 25, 27, 28, 33, 34 |

| Treatment | Surgical closure of the dural defect is mandatory (total cyst excision is controversial) | Removal of LPS | 24–28, 33, 34 |

EDAC: extradural arachnoid cyst, LPS: lumboperitoneal shunt.

The optimal treatment for symptomatic EDAC is closure of the causative dural defect, and aggressive removal of the cyst component remains controversial.25,33,34) According to a review analyzing 52 surgeries involving EDACs, the difference in the recurrence rate between total excision and simple fenestration was not significant (8.3 vs. 3.6%, respectively), suggesting that total cyst excision might have limited benefit in terms of cyst recurrence and clinical outcome.26) Since there are no reports of EDACs associated with LPS placement, optimal strategies against this case need to be carefully determined. The LPS, efficiently managing iNPH for years, was revised to a VPS in order to prepare the following spinal surgery for the EDAC. However, this intervention was sufficient for both gradual disappearance of the cauda equina syndrome and shrinkage of the EDAC. It is likely that withdrawal of the lumbar catheter might have spread the dural defect, leading to resolution of the ball-valve mechanism in the EDAC. At the same time, the newly applied VPS might have aspirated the cyst content along with the cyst wall, thus patching the dural defect.

Lumbar EDACs can develop over years after LPS placement. Under these conditions, shrinkage of the EDAC can be achieved by simple conversion of LPS into a VPS or ventriculoatrial shunt.

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.