2021 Volume 8 Issue 1 Pages 637-643

2021 Volume 8 Issue 1 Pages 637-643

Neurosyphilis is an infection of the central nervous system by Treponema pallidum. Gummatous neurosyphilis, especially spinal syphilitic gumma, is an exceedingly rare manifestation and may be misdiagnosed as other tumors due to its rarity. A 42-year-old man with a medical history of treatment for syphilis presented with rapidly progressive leg paralysis, leg sensory disturbance, and bladder and rectal disturbance. Spinal MRI demonstrated an intradural extramedullary lesion strongly compressing the spinal cord at the T6/7 level, which was accompanied with dural tail sign and perilesional meningeal thickening at the T6–T8 levels. Small intradural extramedullary lesions were also detected at the T1 and T8 levels. Serological and cerebrospinal fluid examinations for syphilis were both positive. In the treatment of spinal syphilitic gumma, the decompression of the spinal cord by lesionectomy followed by postoperative antibiotic treatment is considered to be an optimal procedure in patients with rapid progression of neurological deterioration. In the present case, the symptomatic main lesion that was compressing the thoracic cord was excised by surgery and analyzed by histopathological examination, and another small asymptomatic lesion was resolved by postoperative antibiotic treatment. Spinal syphilitic gumma was diagnosed using both histopathological findings of the surgically resected lesion and another residual lesion that was resolved by postoperative antibiotic treatment.

Syphilis is a chronic infectious disease caused by Treponema pallidum. Syphilis cases have decreased since the widespread use of penicillin; however, the number of patients affected with syphilis has been increasing in recent years. One of the factors associated with this increase is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1–3) Gummatous neurosyphilis is a rare manifestation of a T. pallidum infection of the central nervous system (CNS).4,5) Neurosyphilitic gumma is a differential diagnosis of mass lesions in the CNS among syphilis-positive patients, and may be misdiagnosed as other tumors due to its rarity. Here, we describe a case of multiple spinal intradural extramedullary syphilitic gummas at the thoracic levels. The symptomatic main lesion compressing the thoracic cord was excised by surgery and another small asymptomatic lesion was treated with postoperative antibiotic therapy. Spinal syphilitic gumma was diagnosed by histopathological findings of the surgically resected lesion and the resolution of another residual lesion by postoperative antibiotic treatment.

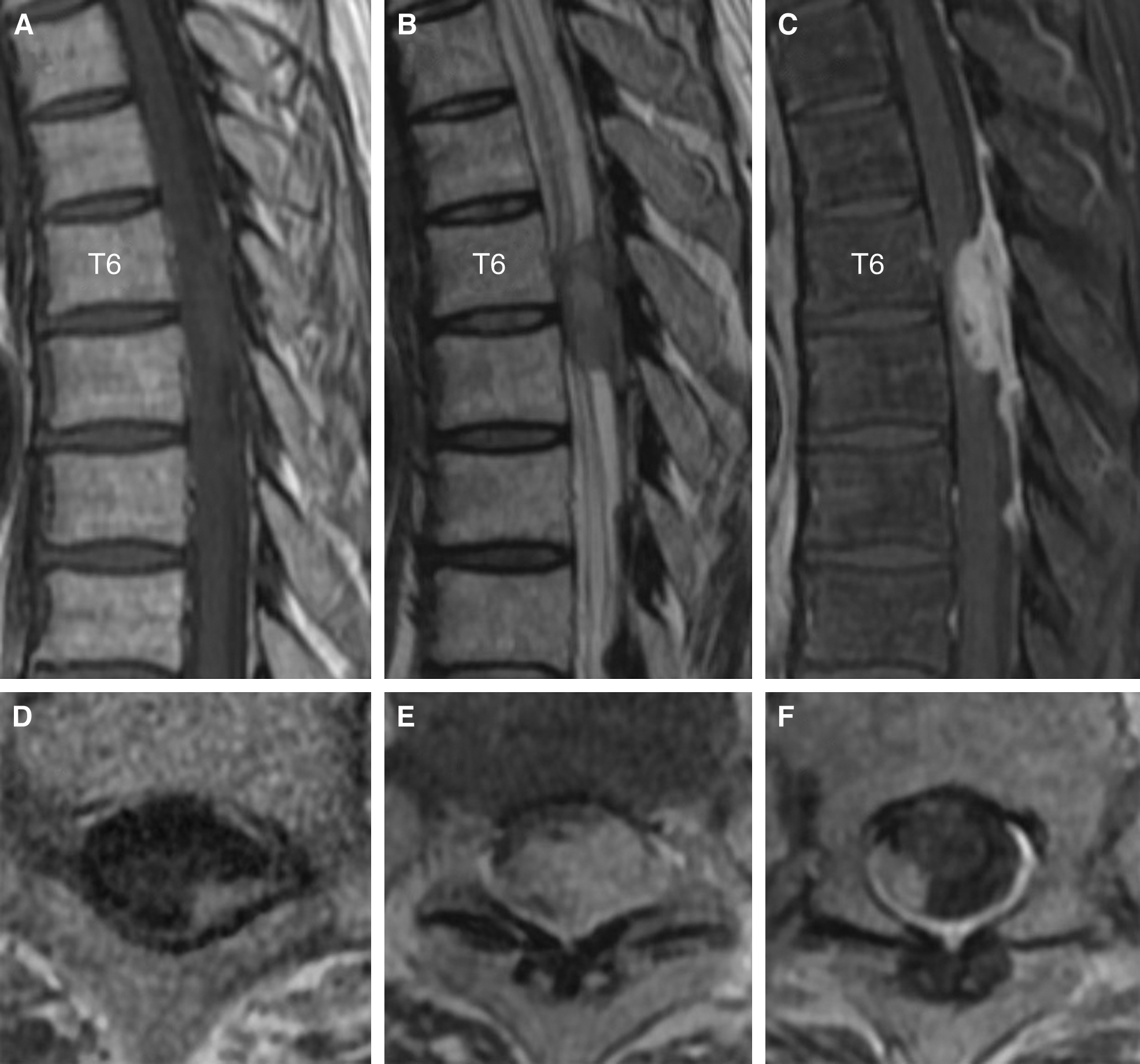

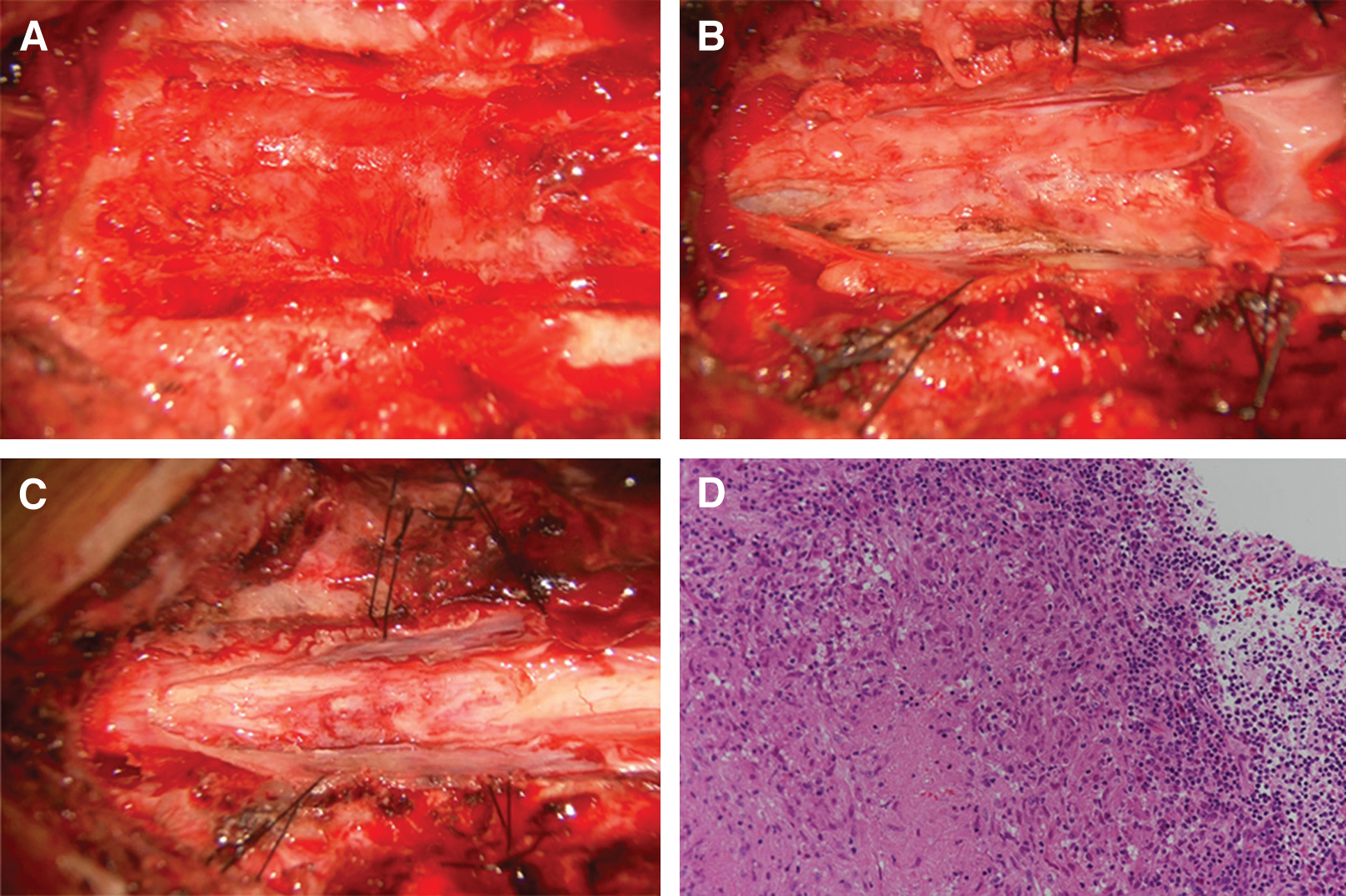

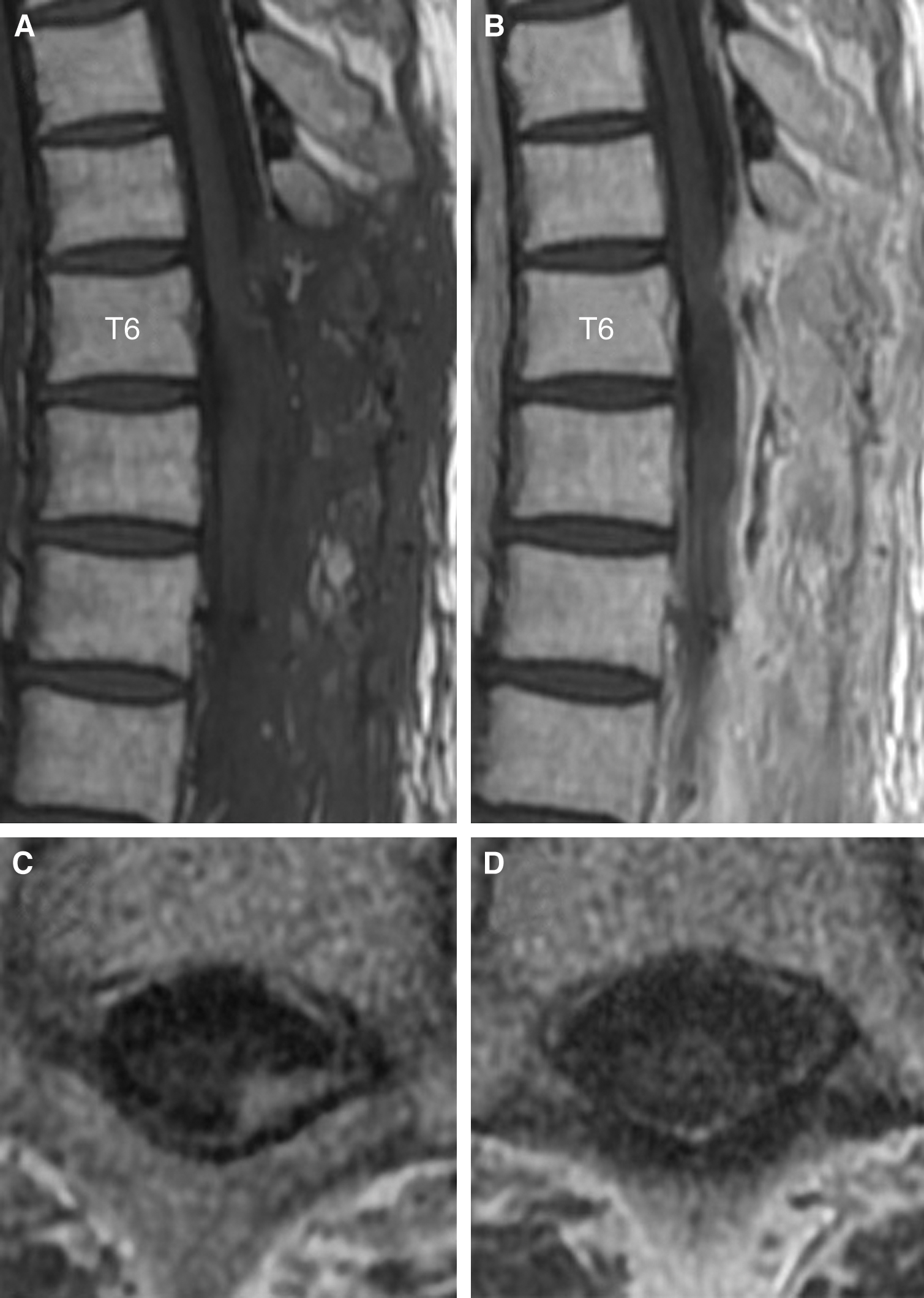

A 42-year-old man with a medical history of treatment for syphilis in his 20s presented with rapidly progressive leg paralysis, leg sensory disturbance, and bladder and rectal disturbance. Neurological examination revealed paraplegia with manual muscle test (MMT) grades of 3/5 in his lower extremities with hypoesthesia below the T7 level. Spinal MRI demonstrated an intradural extramedullary lesion strongly compressing the spinal cord from the left-dorsal side at the T6/7 level, which was accompanied with dural tail sign and perilesional meningeal thickening at the T6–T8 levels. The lesion was isointense on T1-weighted imaging and iso- to slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging, with homogeneous enhancement and small hypointense areas inside the lesion after contrast injection (Fig. 1A–C and 1E). Moreover, small intradural extramedullary lesions with contrast enhancement were detected at the T1 and T8 levels (Fig. 1D and 1F). The main lesions at the T6/7–T8 levels had no continuity with the remote lesion at the T1 level because the dura mater between the T1 and T6 levels was not thickened and had no contrast enhancement. Brain MRI showed no lesions. Rapid plasma reagin and T. pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA) syphilis serology tests revealed positive results (4.4 RU and 314 COI, respectively). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination revealed positive fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) test and TPHA titer was 1:5120. A serological test for HIV was negative. The value of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) antigen 3.9 ng/ml slightly increased. Abdominal CT showed an iso- to slightly hypodense space-occupying lesion (SOL) that was approximately 3 cm in size in the left medial segment of the liver. Differential diagnoses were meningioma, meningeal dissemination, and spinal syphilitic gumma. A few days later, the patient presented with complete paralysis of the legs, and a lesionectomy at the T6/7–T8 levels was performed through dorsal laminectomy of T6–T9. The lesion at the T1 level was conservatively followed-up because it did not exert a mass effect on the thoracic cord. The intradural extramedullary lesion at the T6/7 level, which was whitish, elastic, and hard, had continuity with the dura mater, and strongly adhered to the spinal cord. The contrast-enhanced dura mater at the T6–T8 levels was hard and thickened; however, the dura mater with no contrast enhancement at the T9 level was normal. Microscopically, the lesion with poor blood supply was dissected from the dura mater, detached from the spinal cord, and totally removed under neurologic monitoring. Total resection of the lesion achieved sufficient decompression of the spinal cord (Fig. 2A–C). Histopathological examination revealed an epithelioid granuloma with infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes and plasmatocytes, and with focal necrosis. These histopathological findings were consistent with CNS syphilitic gumma (Fig. 2D). Polymerase chain reaction and culture for T. pallidum using the surgical specimens were both negative. Antibiotic treatment for syphilis was administered with intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g/day for 14 days, followed by intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g/day for 14 days. Follow-up spinal MRI after the antibiotic treatment revealed complete resection of the lesion at the T6/7–T8 levels and sufficient decompression of the spinal cord (Fig. 3A and 3B). Moreover, another residual small lesion at the T1 level was resolved (Fig. 3C and 3D), which also confirmed the diagnosis of spinal syphilitic gumma. As the SOL in the liver was unchanged after the antibiotic treatment, it was considered to have little relevance to the neurosyphilitic gumma. The patient showed a partial recovery of paraplegia with MMT 2/5 in the lower extremities by postoperative rehabilitation with persistence of bladder and rectal disturbance that required the use of a urinary catheter and laxatives. The patient was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital on postoperative day 51.

In the present report, we described a case of multiple spinal intradural extramedullary syphilitic gummas at the thoracic levels that caused rapidly progressive leg paralysis, leg sensory disturbance, and bladder and rectal disturbance. The symptomatic main lesion that was compressing the thoracic cord was excised by surgery, and another small asymptomatic lesion was treated with postoperative antibiotic therapy. To the best of our knowledge, the present report is the first to diagnose spinal syphilitic gumma using both histopathological findings of surgically resected lesion and resolution of another residual lesion treated with postoperative antibiotic therapy.

Neurosyphilis is observed in 4–10% of patients untreated or insufficiently treated for syphilis,6) and it is classified into two stages: early or late neurosyphilis. The incidence of invasion of the CNS by T. pallidum in the early phase of infection is 25–60%; however, early neurosyphilis is almost asymptomatic. Symptomatic early neurosyphilis occurs in approximately 5% of patients, and its main neurological manifestations are meningitis and cranial nerve palsy. Late neurosyphilis is associated with meningovascular and parenchymal involvement, which develops into gumma, tabes dorsalis, and general paresis. Meningovascular neurosyphilis is further grouped into two subcategories: meningeal and vascular; the former develops into meningitis or gumma, and the latter causes cerebral or spinal infarction. Parenchymal neurosyphilis is characterized by tabes dorsalis or paretic dementia.7,8,9) Gummatous neurosyphilis is especially rare among clinical manifestations of neurosyphilis.4,5) Meningitis and gumma are categorized into meningeal neurosyphilis, and gumma forms as a series of meningeal lesions. Neurosyphilitic gumma should be considered as a differential diagnosis of mass lesions in the CNS among syphilis-positive patients. However, neurosyphilitic gumma may be misdiagnosed as other tumors due to its rarity. Furthermore, considering that the overall incidence of spinal cord tumors was only 0.97 per 100000 (2–4% of all CNS tumors),10) the diagnosis of spinal syphilitic gumma is even more difficult among CNS syphilitic gummas due to its rarity.

CNS syphilitic gummas may occur in any region of the intracerebral and intraspinal space.9) In previous studies, spinal syphilitic gumma often occurred at the thoracic levels. This tendency was similar to spinal cord tumors and was considered to be related to the large surface area of thoracic spinal cord. Syphilitic gummas commonly develop from the dura mater and pia mater as a series of meningeal lesions, and previous studies reported that spinal syphilitic gummas often occurred in intradural extramedullary space. On the other hand, some studies reported that spinal syphilitic gummas were found to be intramedullary without meningeal involvement6,9); thus, the pathogenesis of spinal syphilitic gumma need to be further investigated (Table 1). The majority of spinal cord tumors are intradural extramedullary, and the most common pathology is schwannoma followed by meningioma.11) The signal characteristics of MRI findings of CNS syphilitic gummas are as follows: T1-weighted imaging commonly shows a hypo- to isointense lesion, and T2-weighted imaging may reveal a hyper-, iso-, or hypointense lesion with homogeneous enhancement after contrast injection. It is important to differentiate gummas from tumors; thus, perilesional meningeal thickening and enhancement are useful for diagnosis because syphilitic gummas commonly develop from the dura mater and pia mater.12) In the present study, meningioma was first suspected because of the intradural extramedullary lesion with dural tail sign, and second, meningeal dissemination was suspected due to the SOL in the liver, slight increase of SCC, and multiple intradural extramedullary lesions. However, because of the patient’s medical history of treatment for syphilis, syphilis-positive findings in serological and CSF examinations, and perilesional meningeal thickening and enhancement in MRI findings, we considered spinal syphilitic gumma as a differential diagnosis. Previous studies reported cases of spinal syphilitic gumma that was not suspected prior to surgery; however, after postoperative histopathological examination suggested the possibility of spinal syphilitic gumma, it was definitively diagnosed by syphilis-positive findings in an additional serological test for syphilis.8,13) Spinal syphilitic gumma is difficult to diagnose, and although CSF examinations are useful to diagnose CNS syphilitic gumma, negative results in CSF examinations cannot exclude the possibility of CNS syphilitic gumma.2,12)

| Study | Spinal level | Location | Number of lesions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colli et al. (1979)20) | T3 | Intradural extramedullary | 1 |

| El Quessar et al. (2000)21) | C3 | Intramedullary | 1 |

| Wu et al. (2009)22) | T12–L1 | Intradural extramedullary | 1 |

| Molina-Olier et al. (2012)23) | T6–8 | Extradural | 1 |

| Dhasmana et al. (2013)19) | T12–L1, L3, L5 | Intrathecal | 3 |

| Salem et al. (2013)24) | C3–4 | Extradural | 1 |

| Zhang and Tian (2013)25) | T4–5 | Extradural | 1 |

| Zhou et al. (2014)26) | T2–3 | Intradural extramedullary | 1 |

| Yang et al. (2016)9) | C5 | Intramedullary | 1 |

| Shen et al. (2019)12) | C3, C4, C5, T4, T5, S1 | Intradural extramedullary | 6 |

| Cui et al. (2020)6) | T5 | Intramedullary | 1 |

| Mejdoubi et al. (2020)8) | C4–6 | Intradural extramedullary | 1 |

| Present study | T1, T6–7, T8 | Intradural extramedullary | 3 |

Antibiotic treatment of syphilis is based on stage of infection and whether there is evidence of CNS involvement.14) Furthermore, the recommended antibiotic treatment of syphilis without CNS involvement differs between Japan and other countries. In other countries, intramuscular administration of benzathine penicillin G at 24 million U/day is the first-line treatment. In Japan, on the other hand, oral administration of amoxicillin at 1500 mg/day is the recommended treatment because benzathine penicillin G is unapproved. However, in both Japan and other countries, the standard antibiotic treatment for neurosyphilis is intravenous penicillin G administered at 24 million U/day for 14 days. In patients with penicillin allergy, intravenous administration of ceftriaxone at 2 g/day for 14 days is an alternative regimen.1,6,8,9)

In the present case, we made a judgement of emergent decompression of the spinal cord by lesionectomy because the patient presented with complete paralysis of the legs after a few days due to the strong distortion of the spinal cord by the gumma. Previous studies reported that CNS syphilitic gumma was reduced by standard penicillin therapy, thereby avoiding unnecessary surgeries.6,12) However, since antibiotic treatment takes time until CNS syphilitic gumma is reduced, decompression of the spinal cord by lesionectomy should be prioritized and antibiotic treatment performed after histopathological diagnosis in cases with rapid progression of neurological deterioration.8,15) In the present case, intravenous administration of ceftriaxone was selected as the postoperative antibiotic treatment.

Histopathological characteristics of gumma show chronic granulomatous inflammation with infiltration of epithelioid cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, and necrosis is commonly observed in the center of lesions.16) It is rare that T. pallidum is found in pathologic specimens7); however, T. pallidum has been detected in pathologic specimens of cerebral syphilitic gumma.17,18) In the present case, spinal syphilitic gumma was histopathologically diagnosed by surgical resection of the symptomatic main lesion at the T6/7 level, and the resolution of another small asymptomatic lesion at the T1 level by postoperative antibiotic treatment with ceftriaxone also contributed to the diagnosis.

Previous reports described multiple spinal syphilitic gummas.12,19) In the present report, we described a case of multiple spinal intradural extramedullary syphilitic gummas at the thoracic levels that caused rapidly progressive leg paralysis, leg sensory disturbance, and bladder and rectal disturbance. The symptomatic main lesion that was compressing the thoracic cord was excised by surgery and analyzed by histopathological examination, and another small asymptomatic lesion was resolved by postoperative antibiotic treatment, which contributed to the diagnosis of spinal syphilitic gumma.

Neurosyphilitic gumma, especially spinal syphilitic gumma, may be misdiagnosed as other tumors due to its rarity. In patients with rapid progression of neurological deterioration, decompression of the spinal cord by lesionectomy followed by postoperative antibiotic treatment is an optimal procedure. In the present study, the spinal syphilitic gumma was diagnosed in terms of both histopathological findings of the surgically resected lesion and the resolution of another residual lesion by postoperative antibiotic treatment.

The authors declare that they have no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript and its publication, and have registered online self-reported COI Disclosure Statement Forms through the website for the Japan Neurosurgical Society.