2022 Volume 9 Pages 371-376

2022 Volume 9 Pages 371-376

Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection (CAD) is a relatively rare disease, with patients, including those with bilateral CAD, often recovering after conservative therapy. However, patients with symptomatic and progressive disease require urgent carotid artery stenting (CAS). If CAD extends to the petrous portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA), it is difficult to treat with a carotid stent alone. This report describes a rare case of consecutive spontaneous bilateral CAD that required an intracranial stent with an interval of 4 years between the first and second CAS. A 58-year-old man with a history of dyslipidemia was admitted for transient ischemic attacks. He underwent CAS with carotid and intracranial stents on the third day for the left CAD due to exacerbation of symptoms under antithrombotic therapy and new stroke on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). He recovered well. However, 4 years after the initial treatment, the patient was admitted again because of a sudden headache, photophobia, and transient weakness of the left lower limb. He was diagnosed with CAD on the contralateral side. He underwent CAS with carotid and intracranial stents due to progressive neurological deterioration under antithrombotic therapy. After treatment, he was clinically stable without any new infarctions on a follow-up MRI. He was discharged without neurological deficit. Our case of bilateral internal CAD treatment demonstrated that early revascularization with immediate stenting with carotid and intracranial stents in CAD contributes to the prevention of extensive neurological damage, thereby providing a favorable outcome in some cases.

Extracranial internal carotid artery dissection (CAD) is the separation of the arterial wall layers as a result of intimal defect and penetration of the blood flow between them. A spontaneous CAD is relatively rare, and bilateral cases are even more so, particularly those in which dissection occurs simultaneously. The course of the disease is relatively favorable with medical treatment using antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants, and healing of the dissected artery can be expected.1) However, in some cases, urgent carotid artery stenting (CAS) may be necessary if the patient is refractory to medical therapy or hemodynamic infarction is imminent. If CAD extends to the petrous portion of internal carotid artery (ICA), a carotid stent cannot cover the length of the CAD. This report describes a rare case of spontaneous bilateral CADs that occurred consecutively with a 4-year interval, and both required urgent CAS with carotid and intracranial stents.

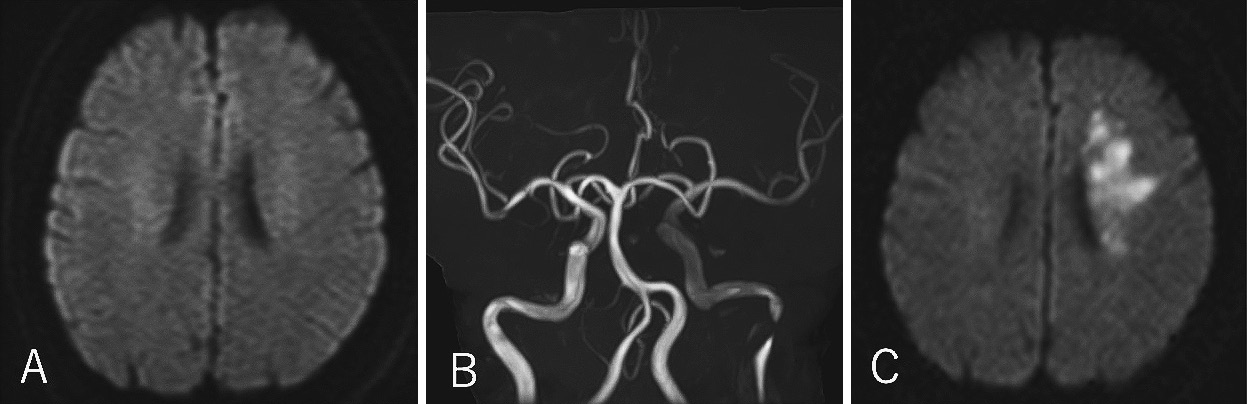

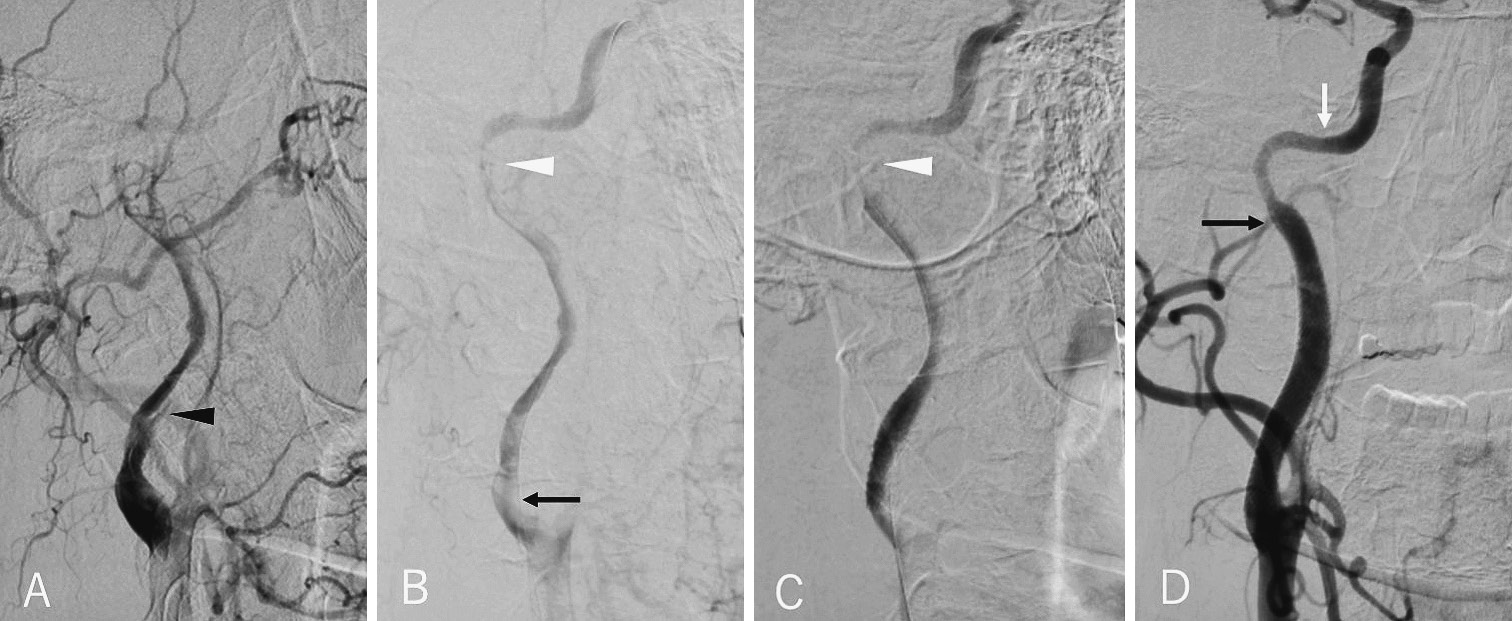

A 54-year-old man with pre-existing hyperlipidemia was admitted with transient weakness in the right upper and lower limbs and dysarthria. On arrival, the patient had almost no neurological deficit. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) -diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) showed no cerebral infarction (Fig. 1A). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed severe stenosis of the left ICA (Fig. 1B), and dissection of the ICA was diagnosed according to digital subtraction angiography. Subsequently, systemic heparinization was initiated. On the third day, the patient's symptoms worsened, with impaired consciousness, paralysis of the right upper and lower limbs, and aphasia. MRI-DWI showed an infarct centered on the watershed area (Fig. 1C), and an urgent left CAS was performed because of DWI-clinical mismatch. Before the treatment, aspirin 200 mg and clopidogrel 300 mg were administered for the purpose of loading. Under local anesthesia, a 9-Fr balloon guiding catheter (Optimo, Tokai Medical Products, Aichi, Japan) was inserted into the left common carotid artery (CCA). Left common carotid angiography (CCAG) showed CAD (Fig. 2A) and a severe stenotic lesion from its bifurcation to the petrous portion of the ICA (Fig. 2B). A micro-guidewire (CHIKAI, ASAHI INTECC, Aichi, Japan) was passed through the CAD, and three carotid artery stents (Precise Pro Rx 6 × 30 mm, Precise Pro Rx 7 × 40 mm, and Precise Pro Rx 8 × 40 mm, Cordis, OH, USA) were deployed from the most distal position from which a carotid artery stent can reach the CCA (Fig. 2C). Residual dissection was detected distally to the first stent. Therefore, an intracranial stent (Neuroform EZ 4.5 × 30 mm, Stryker, Fremont, CA, USA) was deployed. The final imaging confirmed adequate blood flow through the CCA to the ICA (Fig. 2D). After the treatment, the impaired consciousness and paralysis improved and only very mild dysphasia persisted (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] 1). Dual antiplatelet therapy was gradually decreased and was discontinued after 2 years.

Initial findings before the first CAS treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) showed no cerebral infarction (A). Magnetic resonance angiography showed severe stenosis of the left internal carotid artery (B). MRI-DWI on the third day showed enlarged infarct centered on the watershed area (C).

Intraoperative findings of left common carotid angiography. A false lumen (black arrowhead) was detected on the internal carotid artery (ICA) (A). The dissection extended from the bifurcation (black arrow) to near the petrous portion (arrowhead) of the ICA (B). Residual stenosis in the distal part of the dissection (arrowhead) after the deployment of the carotid artery stents (C). Adequate dilation of the left ICA and improvement of flow (white arrow, the distal edge of the neck-bridge stent; black arrow, the proximal edge of the neck-bridge stent) (D).

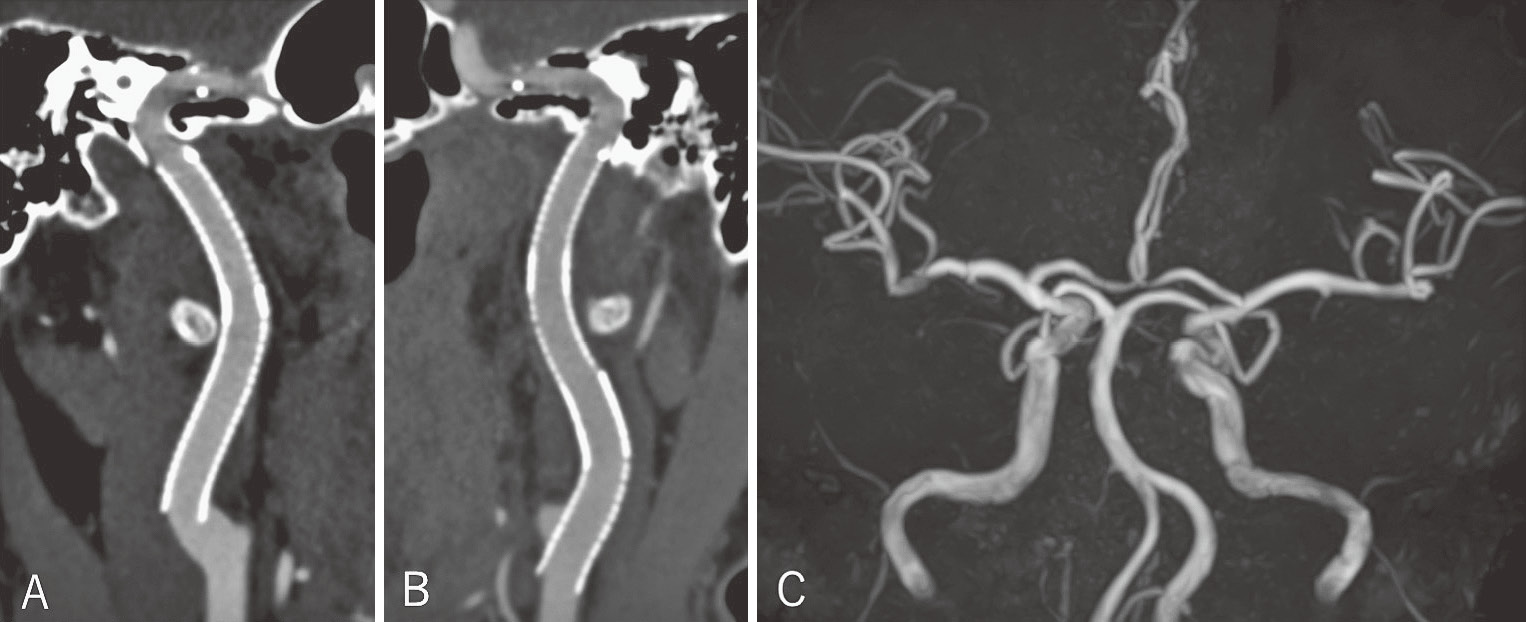

Approximately 4 years after the clinical onset of the carotid dissection, the patient was admitted again with transient weakness of the left lower limb, photophobia in the right eye, and a headache. MRI-DWI did not show cerebral infarction (Fig. 3A). An MRA revealed severe stenosis of the right ICA (Fig. 3B), and anticoagulation (argatroban) and dual antiplatelet therapy were initiated immediately. On the morning of the next day, the patient developed left hemiparesis. MRI-DWI showed cerebral infarction in the right "watershed" region (Fig. 3C), and CT-perfusion imaging showed low perfusion of the right hemisphere (Fig. 3D). Therefore, urgent CAS was performed in the same manner as the first treatment. The right CCAG showed CAD from the bifurcation to the petrous portion of the ICA (Fig. 4A, B). Two carotid artery stents (Precise Pro Rx 6×30 mm and Precise Pro Rx 7 × 40 mm) were deployed from the proximal petrous portion to the orifice of the ICA (Fig. 4C). Because there was residual stenosis in the distal part of the dissection, an intracranial stent (Neuroform Atlas 4.0 × 21 mm, Stryker) was also deployed. The final imaging confirmed that the stents were well expanded (Fig. 4D). After postoperative rehabilitation, the hemiparesis improved and the patient was discharged (mRS 0). Dual antiplatelet therapy was discontinued after 2 years. Neither CAD has recanalized after 4 years of follow-up (Fig. 5).

Preoperative findings before the second CAS treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) showed no cerebral infarction (A). Magnetic resonance angiography showed severe stenosis of the right internal carotid artery (B). MRI-DWI showed a spotty infarct centered on the watershed area (C). Perfusion image showed low perfusion for the right middle cerebral artery territory (D).

Intraoperative findings of the right common carotid on angiography. A false lumen (black arrowhead) was detected on the internal carotid artery (ICA) (A). The dissection extended from the bifurcation (black arrow) to near the petrous portion (arrowhead) of the ICA (B). Residual stenosis in the distal part of the dissection (arrowhead) after the deployment of the carotid artery stents (C). Adequate dilation of the right ICA and improvement of blood flow (white arrow, the distal edge of the neck-bridge stent; black arrow, the proximal edge of the neck-bridge stent) (D).

Multiplanar reconstruction images of three-dimensional computed tomography (A, right side; B, left side) and magnetic resonance angiography (C) showed no recanalization of the internal carotid artery dissection after 4 years.

The patient's consent and application for off-label use were obtained for this case report.

CAD is a relatively rare disease, occurring in approximately 2.6-2.9 per 100,000 people.2,3) Bilateral CAD occurs in 10%-17% of cases.4-6) It is often found at the same time, and reports suggest that on rare occasions, CAD may recur 2 days to 8.6 years after the initial event.2) Most recurrences occur within a month, and thereafter, they occur at a rate of 1% per year. There are some reports of treatment of both sides almost simultaneously, but there are no reports of patients who become symptomatic on the contralateral side and who needed an intracranial stent.7-11)

Causes are often classified as 1) a sudden critical increase in arterial pressure (e.g., in women during delivery), 2) previous infection, 3) hyperhomocysteinemia, 4) migraine, 5) trauma, or 6) previous medical procedures on the arteries. Moreover, connective tissue pathologies such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV or fibromuscular dysplasia carry with them a predisposition to CAD.12,13) Eagle's syndrome is also reported as a typical example that demonstrates the morphological and mechanical factors that induce the dissection of the ICA.14) In our case, there were no such findings. Generally, symptoms include neck pain, headache, eye pain, facial pain, Horner's syndrome, and sometimes cerebral infarction symptoms due to CAD. More than 90% of cerebral infarctions are caused by artery-to-artery embolism. Hemodynamic impairment due to decreased blood flow is another cause.

CAD prognosis is relatively good, with approximately 60% of patients recovering completely and 20% improving with conservative treatment. Moreover, 97%-100% of stenotic cases and 60% of occlusive cases recanalize spontaneously.11) Antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation therapy is indicated if artery-to-artery embolism is present. Evidence of the superiority of either antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation therapy is lacking at present.15,16) In CAD patients with hemodynamic impairment presenting as progressive stroke or recurrent ischemic symptoms, despite adequate medical treatment, surgical reconstruction should be considered.16,17) Hemodynamic impairment is well detected on perfusion images.17) Treatment includes CAS and direct bypass. CAS was selected in our case because the ICA was not completely occluded.

Stents that can be used to treat CAD include carotid artery stents and intracranial stents. Carotid artery stent use includes both open-cell and closed-cell stents, and the stent should be selected according to the configuration of the artery, the tortuosity of the vessel, and the dimensions at the tip of the stent system. In our case, we used open-cell-type carotid artery stents because the ICA was slightly tortuous. If the CAD continues to the petrous portion, a carotid artery stent cannot be guided, and therefore, an intracranial stent is required.

Previously used intracranial compatible stents for CAD include coronary stents, atherosclerotic stents, aneurysm neck-bridge stents, and flow-diverter stents.18,19) Coronary stents are balloon-expandable stents that are relatively inflexible and difficult to guide in the petrous portion. Additionally, balloon-expandable stents are inherently noncompliant and can exert traumatic radial force during deployment in dissected vessels, leading to further dissection. Arteriosclerotic stents (Wingspan stenting system, Stryker) have a maximum length of only 20 mm and are of the over-the-wire type, making them unsuitable for the additional stenting as required in our case. There are three types of aneurysm neck-bridge stents: closed-cell, braided, and open-cell stents.20) When closed-cell stents are deployed around tight curves, such as the petrous portion of the ICA, incomplete stent apposition may contribute to increased thromboembolic events. Braided stents are substantially more thrombogenic than other types of stents in emergency cases where antiplatelet function is difficult to assess.19) Flow-diverter stents are also braided stents and are associated with risks in emergency cases. In our case, we used a self-expanding, laser-cut stent with an open-cell design (Neuroform/Neuroform Atlas, Stryker) for residual CAD in the petrous portion of the ICA. This is because the stent can be deployed simply unsheathe, fits easily, has good conformability with vascular discrepancy, and has a low risk of thrombosis compared to braided design stents.

In conclusion, this report describes a case of consecutive bilateral CAD that was successfully treated with carotid artery and intracranial stents. Endovascular stenting is a minimally invasive and effective procedure for CAD patients with medically resistant low perfusion and progressive clinical deterioration. When CAD occurs on one side, the same treatment may be required on the other over time, and open-cell-type intracranial stents are safe and effective.

We wish to thank Dr. Kostadin Karagiozov for his advice and editing the manuscript.

All authors report no conflicts of interest concerning this article.