論文ID: cr.2018-0147

論文ID: cr.2018-0147

Lumbar spondylolysis is commonly recognized at a single-level of the lumbar spine and frequently affects the L5 pars interarticularis unilaterally or bilaterally. Some reports have described multiple-level spondylolysis, most cases of which occur at consecutive lumbar segments. We herein present a rare case of lumbar spondylolysis involving nonconsecutive multiple-level segments; only eight such cases have been reported previously. A 38-year-old man presented with a 10-month history of chronic severe low back pain. Lumbar flexion–extension radiographs and computed tomography revealed spondylolysis at the level of L3 and L5, whereas no spondylolisthesis was present and the intervertebral disc spaces were maintained at all levels. Because 6 months of conservative management failed and repeated diagnostic blocks confirmed that the fracture of the L3 pars interarticularis was generating pain, repair of the bilateral L3 pars interarticularis with the smiley face rod method was performed. At the last follow-up 1 year after surgery, the patient had resumed normal life as a laborer and reported no back pain.

Lumbar spondylolysis is caused by repetitive stress of the pars interarticularis with subsequent microfracture which may lead to bony defect or spondylolisthesis.1,2) It is usually recognized at a single level in the lumbar spine and frequently affects the L5 pars interarticularis unilaterally or bilaterally.1,2) Some reports have described multiple-level spondylolysis, most cases of which are located at consecutive lumbar segments.3–8) Non-consecutive multiple-level spondylolysis affecting the lumbar spine is rare; to our knowledge, only eight such cases have been documented in the literature (Table 1).1,8–12) We herein describe a 38-year-old man with noncontiguous multiple-level spondylolysis at L3 and L5 that was successfully treated with single-level repair of the pars interarticularis at L3. The preoperative management and surgical strategy used for this patient are discussed.

| Authors | Age/sex | Physical activity | Symptom | Level | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ravichandran (1980) | 33/M | Rugby player | LBP + bilateral leg pain | L3 + L5 | Intertransverse fusion of L2–L4 |

| 43/M | Manual labor | LBP + right leg pain | L2 + L4 | Repair of L2 by Buck method + L4–S1 interspinous fusion | |

| Ranawat et al. (2003) | N/A | Cricket player | N/A | L1 + L3 + L5 | Repair of L5 by screw placement into the defects |

| Chung et al. (2007) | 20/M | N/A | N/A | L3 + L5 | Repair of L3 + L5 by screw and hook method |

| 20/M | N/A | N/A | L3 + L5 | Repair of L3 + L5 by screw and hook method | |

| Nayeemuddin et al. (2011) | 16/M | Football player | LBP | L3 + L5 | Conservative treatment |

| Elgafy et al. (2015) | 18/M | Baseball player | LBP | L2 + L5 | Repair of L2 by screw and hook method |

| Voisin et al. (2018) | 50/M | N/A | LBP + right leg paresthesia | L3 + L5 | Repair of L3 + L5 by smiley face rod method |

| Present case | 38/M | Manual labor | LBP | L3 + L5 | Repair of L3 by smiley face rod method |

M: male, Age is presented in years, LBP: Low back pain.

An otherwise healthy 38-year-old man working as a manual laborer presented with a 10-month history of chronic severe low back pain. Conservative treatment including administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and use of an orthosis had been conducted by his home doctor for the previous 6 months, but this treatment was unsuccessful. At the presentation neurological examination revealed no motor weakness or sensory disturbance in the bilateral lower extremities. Dynamic lumbar radiographs showed no spondylolisthesis, and the intervertebral disc spaces were maintained at all levels; however, spondylolysis at L3 and L5 was suspected (Figs. 1A and 1B). Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed degeneration of the L3/4 and L5/S1 discs (Fig. 1C). A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed bilateral defects with marginal sclerosis at the pars interarticularis of L3 and L5 with mild spinal canal stenosis and no foraminal stenosis. Additionally, osteophyte formation was observed around the L3 but not L5 pars interarticularis (Figs. 2A–2E). Based on this finding, we speculated that unstable micromovement around the L3 pars interarticularis had caused the low back pain. To confirm this speculation and relieve the patient’s severe back pain, the fracture of the L3 pars interarticularis was injected with lidocaine and steroids under fluoroscopic guidance. Immediately after injection, the patient reported pain relief, which lasted for several weeks. One month after the injection, the pars interarticularis was injected again because of recurrent severe lumbago. At this time, the fracture of the L5 pars interarticularis was injected for confirmation, but this injection resulted in no pain relief. Therefore, the L3 pars interarticularis was injected, resulting in immediate pain relief. Because 6 months of conservative management failed and the diagnostic block indicated that the fracture of the L3 pars interarticularis was generating the pain, surgical treatment was recommended for the L3 pars interarticularis.

Preoperative lumbar radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging. In the lateral lumbar (A) flexion and (B) extension radiographs, no spondylolisthesis was present and the intervertebral disc spaces were maintained at all levels; however, spondylolysis at the levels of L3 (arrowhead) and L5 (arrow) was suspected. (C) A midsagittal magnetic resonance T2-weighted image showed degeneration of the L3/4 and L5/S1 discs.

Preoperative computed tomography (CT). (A) Right and (B) left parasagittal CT scans demonstrated bilateral L3 pars fracture with osteophyte formation (arrowhead) and L5 pars fracture (arrow) without osteophyte formation. Axial CT scans demonstrated (C) marginal sclerosis with osteophyte formation at L3 and (D) pseudarthrosis without osteophyte formation at L5. No spondylolisthesis was present, and the intervertebral disc spaces were maintained at all levels.

Although MRI revealed slight degeneration of the L3/4 disc (Fig. 1C), bilateral repair of the L3 pars interarticularis rather than L3/4 fusion surgery was indicated because the radiographic findings demonstrated no spondylolisthesis and maintenance of both the intervertebral disc spaces and mobility of L3/4 (Figs. 1A and 1B).

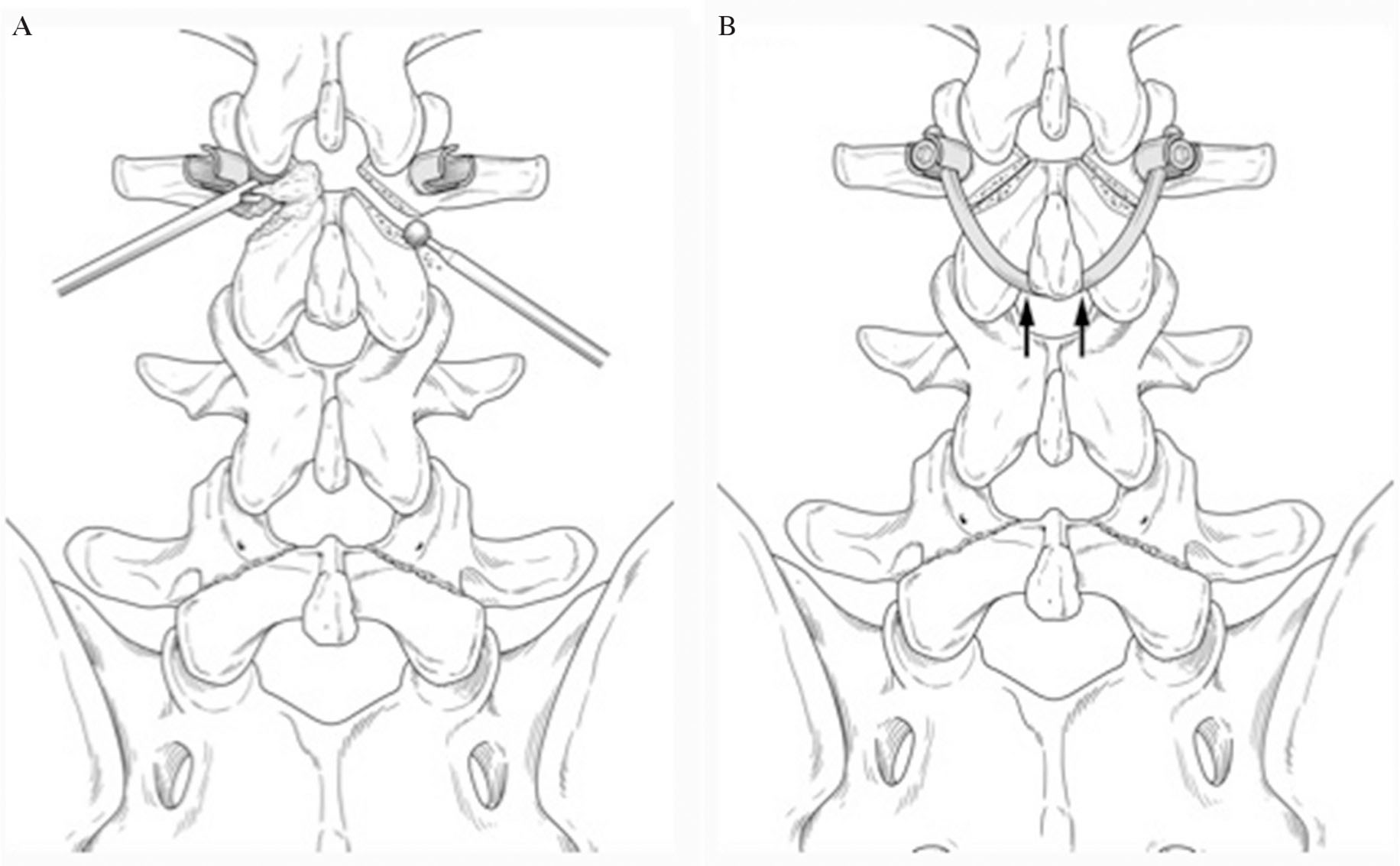

SurgeryOf several reported methods of direct repair, the smiley face rod method was adopted.13) A 7-cm midline skin incision was made, and the paraspinal musculature was retracted laterally to expose the bilateral L3 lamina, pars interarticularis, and transverse process. Using anatomic landmarks and fluoroscopic guidance, a starting hole for the pedicle screw was burred, the hole was tapped, and bilateral multiaxial pedicle screws were inserted (Fig. 3A). The pars interarticularis defect and osteophyte around it were exposed. Using a diamond surgical bur and curette, the osteophyte and synovium of the pseudarthrotic part of the spondylolytic segment was removed to refresh the defects. Cancellous bone was harvested from the iliac crest and placed in the defect before screw insertion. A 100-mm-long rod was bent to fit and placed immediately caudal to the L3 spinous process. The loose lamina was fixed more firmly after the bent rod was bumped against the spinous process using a rod pusher (Fig. 3B). Cancellous bone was implanted into the pars defects (Figs. 4A and 4B).

Illustration of the surgical procedure. The defect of the L3 pars interarticularis was exposed and curetted, then refreshed using a diamond burr. (A) Bilateral L3 pedicle screws were inserted. (B) When the bent rod was bumped against the spinous process using a rod pusher, the loose lamina was firmly fixed.

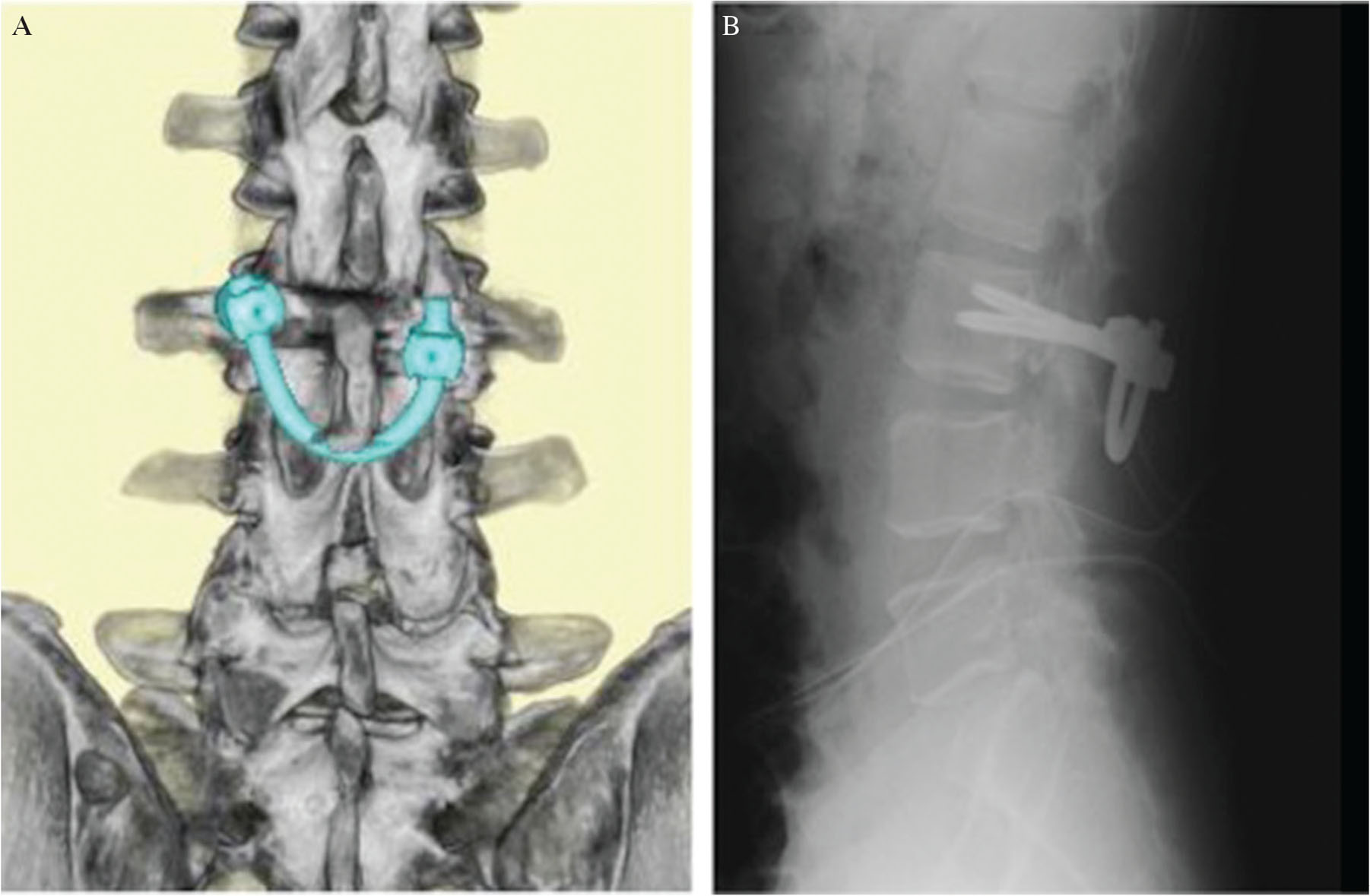

Postoperative radiographs. (A) Lateral lumbar radiograph and (B) three-dimensional computed tomography.

The patient’s post-operative course was uneventful, and his symptoms improved immediately. He was allowed to stand and walk 2 days after the surgery with a hard brace, and he resumed his work as a laborer 1 month after surgery. Six months postoperatively, the patient reported no back pain, and advanced activity was tolerated without problems.

Lumbar spondylolysis most commonly occurs at a single spinal level and usually responds well to conservative treatment; however, some patients’ symptoms do not improve and require surgical intervention.1,2) The main surgical methods are posterolateral arthrodesis and direct repair. Posterolateral arthrodesis of the posterior elements has been commonly performed for years. However, a disadvantage is loss of motion at the affected segment, which increases loading on the adjacent segment.14) Direct repair has the advantage of preserving the segmental motion, which is preferred in younger patients without severe disc degeneration or instability. Several methods of direct repair have been reported to date. In 1968, Kimura15) first reported pars interarticularis repair without instrumentation; however this technique had a disadvantage in that prolonged bed rest and immobilization were required. In 1970, Buck16) reported fixation of the pars with a screw across the pars defect. Proper placement of screws was subsequently considered to be technically difficult. The wiring method, a procedure used to stabilize the loose posterior arch with wire, was described in 1992. However, this technique also had a shortcoming in that placement of the wires under the transverse process was difficult and caused significant bleeding.17) In 2005, Roca et al.18) introduced the pedicle screw and hook method, a procedure used to compress pars defects with pedicle screws and angled lamina hooks. Good clinical and biomechanical results have been reported by this method; however, the surgical results of this method were significantly better among patients ≤20 years than ≥21 years of age.18) In the present study, we repaired the pars interarticularis with the smiley face rod method. This method was first reported in 1999 by Gillet and Petit,19) who called it the “V-rod method.” The screw head and rod resemble a smiley face on the anteroposterior plain radiograph; thus, this technique came to be known as the “smiley face rod method.”13) Ulibarri et al.20) reported that biomechanical evaluation of this method showed excellent stability of a spondylolytic defect in comparison with other types of direct repair surgery.

The incidence of the spondylolysis varies according to race. Previous studies have shown the lowest incidence (1–2%) in the African population and the highest incidence (about 50%) in the Inuit population.21,22) An incidence of about 6% has been reported in the Asian population.21,22)

As for multiple-level spondylolysis, 0.3–5.6% of the incidence have been reported, and most such cases involve consecutive lumbar segments.3,5,8)

Multiple-level spondylolysis has also been reported to be more often seen among men than women, and most cases are associated with sports, trauma and heavy labor.3–9) Therefore, similar to single-level spondylolysis, the mechanical factor is considered to play a decisive role for pathogenesis of multiple-level spondylolysis.9) Despite the fact that single-level pars defects respond well to conservative treatment, conservative measures for multiple-level spondylolysis patients often fail and surgery is frequently required.3,6,8)

In patients with multiple-level spondylolysis without spondylolisthesis, satisfactory surgical results of direct repair of pars interarticularis and posterolateral arthrodesis have been reported.10)

Only eight previous cases of nonconsecutive multiple-level lumbar spondylolysis have been reported (Table 1).1,8–12) Of these eight cases, pars fractures were recognized at L3 and L5 in five patients. All seven patients whose sex was confirmed were male and all five patients whose physical activity was confirmed were athletes, supporting the notion that mechanical factors are also a main contributor to the pathogenesis of nonconsecutive multiple-level lumbar spondylolysis. Conservative treatment was successful in one patient,11) but surgical treatment was performed in the other seven patients because of failed conservative treatment.1,8–10,12) Of these seven surgically treated patients, intertransverse fusion was performed for one patient6) and direct pars repair using a screw and hook system was performed for three patients.9,10) As described above, the smiley face rod method was used for our patient because he was 38 years old and previous reports have indicated excellent stability of spondylolytic defects when using this method in comparison with other direct repair surgeries.20) Furthermore, Voisin et al.12) recently reported good surgical results of the smiley face rod method in a 50-year-old patient with L3 and L5 spondylolysis.

Previous researchers have recommended that the pain source should routinely be confirmed before surgery by infiltration of a local anesthetic in the defects.23,24) We performed repeated blocks for the pars interarticularis to isolate the symptomatic level in our patient with nonconsecutive lumbar spondylolysis. Furthermore, Elgafy et al.9) isolated the symptomatic level using both a block for the pars interarticularis and SPECT scan, and repair of the pars interarticularis was performed only for the symptomatic level. Increased radionuclide uptake within the pars indicates a stress reaction and possibly a more acute pathology; this is therefore considered to be a useful test for a more accurate diagnosis.25)

The upper lumbar spine was symptomatic in both our case and that described by Elgafy et al.9) In addition, patients with multiple-level spondylolysis usually develop spondylolisthesis at L4 and L5 (mostly at L4). In contrast, single-level isthmic spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs at L5.26) The upper level might be likely to become symptomatic in such cases; however, accumulation of more cases of symptomatic consecutive or nonconsecutive multiple-level spondylolysis with confirmation of the symptomatic levels is necessary to confirm this.

In conclusion, we have described a rare case of nonconsecutive spondylolysis successfully treated with primary repair of a single level using the smiley face rod method. This case report emphasizes the importance of preoperative examination including repeated blocks for the pars interarticularis to identify the symptomatic level.

We thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac), for editing a draft of this manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.