Abstract

High-energy precursors can provide access to highly labile reactive intermediates, enabling unprecedented transformations under mild conditions. This review highlights a series of hypervalent λ3-haloganes, focusing on the λ3-iodanyl, λ3-bromanyl, and λ3-chloranyl groups as hypernucleofugic leaving groups. We also summarize recent studies on the generation and chemical reactivity of diatomic carbon (C2) and m-benzyne, which can be best described as highly stabilized singlet biradicals.

1. Introduction

The octet rule is one of the most fundamental principles in chemistry. However, molecules containing higher period elements (generally above the 3rd period) sometimes break this rule as they can formally accommodate more than 8 electrons within a valence shell through three-center-four-electron (3c-4e) bonding, which is generally called “hypervalent” bonding1) Group 17 elements (halogens), especially iodine, have played an important role in the history of hypervalent chemistry because of their unique physicochemical properties and intrinsic reactivity (vide infra).2)–7) For instance, ArIL2 and ArIL4 (Ar: aryl group, L: heteroatom ligand), which have decet/dodecet structures and are designated as organo λ3- and λ5-iodanes (according to IUPAC rules, nonstandard bonding numbers are shown by λn notation), have been extensively investigated for over a century. In these compounds, the aryl group is bound to the iodine atom by a normal two-electron covalent bond, whereas the orthogonal L–I–L triad exhibits hypervalent 3c-4e bonding involving two lower-energy molecular orbitals: a covalent bonding orbital and a nonbonding orbital (Fig. 1).

(i) Physicochemical characters. Owing to the electronic structure of the higher-energy nonbonding orbital with a node on the iodine center, partial positive charge develops on the central iodine atom, which results in electrophilic/Lewis acidic and potent electron-withdrawing character. For example, diphenyl-λ3-iodane 1 has been estimated to show a Mayer’s Lewis acidity scale value LA of 0, comparable to a moderate Lewis acid BPh3,8),9) which is readily tuneable by varying the substituents,10) and a phenyl-λ3-iodanyl group [–I(Ph)FBF3] (FBF3 represents the existence of I···F interaction) acts as a potent electron-withdrawing group (EWG) with a Hammett σp constant of +1.37,11) far larger than those of common strong EWGs such as an –NO2 group (σp +0.78) or –N+Me3 group (σp +0.82) (Fig. 2).12) A pentavalent λ5-iodanyl group –IF4 group also serve as a super-EWG with a σp constant of +1.15.

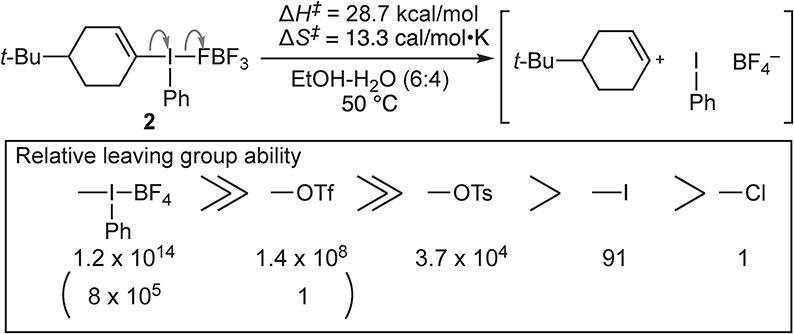

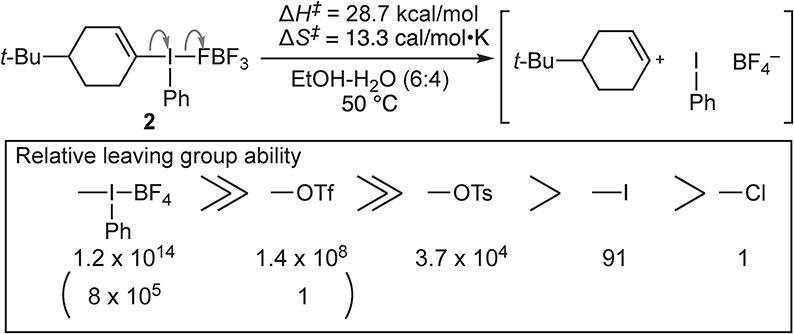

Another fascinating feature of the λn-iodanyl group is its extremely enhanced leaving group ability (nucleofugality). Since Group 17 elements are the most right-aligned in the periodic table (except for noble gases), they show the highest electronegativity and hence, are the least oxidizable elements. For instance, iodine has the highest ionization energy of 10.45 eV among the 5th period elements.13) Therefore, once organohalogen compounds are oxidized to λn-haloganes, they readily undergo energetically favorable reductive elimination of the λn-haloganyl group (dissociation reaction). In 1995, Okuyama, Ochiai, and co-workers determined the leaving group ability of phenyl-λ3-iodanyl group [-I(Ph)FBF3] based on the solvolysis rate of cyclohex-1-enyl(phenyl)-λ3-iodane 2 at 50 °C.14) They found that this leaving group shows about a million times greater nucleofugality (i.e., it is a “hyperleaving group”) than that of triflate, one of the strongest leaving groups commonly used in organic synthesis (Fig. 3).

This superior nucleofugality has allowed the generation of labile intermediates such as bent cyclohex-1-enyl cation 3,14) highly strained cycloalkynes 4,15),16) o-aryne 5,17) unstabilized phenyl and alkynyl radicals 6 and 7,18) alkylidene carbene 8,19) bis(sulfonyl)carbene 9,20) etc. under mild reaction conditions (Fig. 4). These findings not only shed light on the intrinsic character of the intermediates in solution, but also provide methodology to open up new avenues in organic synthesis.

2. Chemistry of hypervalent organo-λ3-bromanes

In contrast to the hypervalent iodine species, the chemistry of which blossomed in the 20th century, only limited work has been done on the chemistry of hypervalent bromine compounds (organo-λ3-bromanes), mainly due to the lack of efficient, user-friendly synthetic methods.21) Direct oxidation of the halogen atom–a key approach in hypervalent λ3-iodane synthesis– is not applicable to the preparation of organo-λ3-bromanes. This limitation is attributed to the higher electronegativity of bromine (χ = 2.96) compared to iodine (χ = 2.66, Pauling’s scale),22) as well as the higher ionization potential of bromoarene (e.g., PhBr: 8.98 eV vs. PhI: 8.69 eV).23) These electronic factors render the oxidative formation of organo-λ3-bromanes unfavorable. For instance, treatment of bromoarene with strong oxidants such as ozone, fluorine gas (F2), or various peroxides typically results in destructive/dearomative oxidation of the aromatic ring rather than the formation of hypervalent bromine species (Fig. 5). Oxidation of 2,6-bis[bis(trifluoromethyl)(hydroxy)methyl]bromobenzene 10 by BrF3 and a recent electrochemical oxidation of [bis(trifluoromethyl)(hydroxy)methyl]bromoarene 12 are rare exceptions to this trend.24),25) In these cases, the neighboring groups assist in the clean oxidation of the Br atom by coordination of oxygen.

Therefore, the synthesis of organo-λ3-bromane still relies predominantly on the nucleophilic trapping of electrophiles (cation/carbene) with a bromine atom (electrophilic trapping approach)26),27) or ligand exchange of highly toxic and extremely reactive BrF3 with arylstannane, arylmercury, or arylborane compounds, as developed by Nesmeyanov et al.28),29) This lack of access has obstructed the application of the otherwise attractive λ3-bromane family (Fig. 6).

In 1984, a monumental study on the synthesis of hypervalent bromine(III) compounds was reported by Frohn et al.30) Their method involves electrophilic substitution of less electrophilic aryl(trifluoro)silane with BrF3, selectively affording thermally stable difluoro(aryl)-λ3-bromane 16 (Fig. 7). The two difluoro ligands in 16 undergo facile ligand exchange with a variety of carbon/heteroatom ligands. Ochiai, Miyamoto and co-workers found that “Frohn’s reagent” not only serves as a pivotal platform for unsymmetrical alkynyl-/vinyl-(aryl)-λ3-bromanes 17, 18,31)–34) bromonium ylides 19,35) and imino-λ3-bromane 20,36) but also acts as an unprecedented oxidant, for example, enabling Hofmann rearrangement of sulfonamides37) and Baeyer-Villiger oxidation of primary aliphatic aldehydes,38) neither of which can be realized with the heavier and less reactive iodine(III) analogues. Concerted C–H amination of unactivated hydrocarbons with 2039) and the vinylic SN2 reaction of 18 with weakly coordinating superacid counter ions33) were also unprecedented. The extraordinary reactivity of these λ3-bromanes arises from the following characteristics of the λ3-bromanyl group: 1) potent electron-withdrawing ability (Hammett σI: 1.63 for the –Br(Ph)BF4 group)40) and 2) excellent leaving group ability (the –Br(Ph)BF4 group shows ca. 106 times greater nucleofugality than the iodine(III) analogue).41)

3. Chemistry of hypervalent organo-λ3-chloranes

Although hypervalent organo-λ3-chloranes were discovered in 1952, they have received much less attention than heavier Group 17 analogues owing to the lack of available synthetic methods.42) Owing to the higher electronegativity of chlorine (χ = 3.16, Pauling’s scale), the oxidative approach employed for iodoarenes is not applicable. As a result, synthetic methods for organo-λ3-chloranes are essentially limited to electrophile trapping methods (see Fig. 6). The synthesis of diphenyl-λ3-chlorane 21 was firstly reported by Nesmeyanov et al. and later slightly improved by Olah et al., involving the thermal solvolysis of aryldiazonium tetrafluoroborate/hexafluorophosphate salts in chlorobenzene (Fig. 8).43),44) These reactions however suffer from concomitant Balz-Schiemann and/or Friedel-Crafts reactions of the in-situ-generated phenyl/aryl cation.

In 2019, we dramatically improved the yields of diaryl-λ3-chloranes (up to 99%) by using a carefully designed diazonium salt.45) This reaction proceeds under ambient conditions (rt, in air) without of the need for any special techniques. The key to this achievement was the use of a chemically inactive and negligibly nucleophilic counterion, tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate B(C6F5)4, which shuts down undesired trapping of the aryl cation by the counter ion. Another critical feature of the molecular design strategy is the installation of ortho- and para-methyl groups to introduce steric protection around the aryl Csp2-cation, together with hyperconjugative stabilization. The mesityl(aryl)-λ3-chloranes 22 not only serve as electrophilic arylating agents when exposed to enolate, but also undergo palladium-catalyzed transformations (triarylphosphine-trapping, Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling, and Mizoroki-Heck reaction) (Fig. 9A). These results are marked contrast to the aryl chloride generally requires elevated temperatures and/or sophisticated ligand system.46) In addition, 22 serves as a stabilized mesityl cation-equivalent under mild conditions (Fig. 9B). Thus, 22 enables mesitylation of benzene (Friedel-Crafts arylation), acetonitrile (Ritter reaction), diaryl sulfide, pyridine, iodoarenes, bromoarenes, and chloroarenes. Notably, except for benzene arylation, the mesitylation proceeds selectively at the most nucleophilic position. For instance, trans-1-iodo-1-propene 23 undergoes mesitylation at the iodine atom, producing vinyl-λ3-iodane 24, which serves as an excellent electrophilic vinylating agent, where the reaction proceeds with inversion of stereochemistry (Fig. 9C).

4. Hypervalent halogane-driven generation of reactive intermediates

Historically, the generation and characterization of reactive intermediates have played important roles in elucidating how chemical reactions proceed. For example, a wide variety of reactive intermediates, such as cations, anions, radicals, carbenes, and arynes, were discovered in the early 20 century, which greatly contributed the development of the electronic theory of organic chemistry.47)

It occurred to us that the vastly enhanced leaving group ability of hypervalent λ3-haloganyl group could be an effective driving force for generating unprecedented reaction intermediates (see also Fig. 4) under mild conditions (low temperature, in solution, without light irradiation, etc.), and might enable us to study the physicochemical properties and chemical reactivity of the intermediates in detail. In the following sections, we will focus on diatomic carbon (C2) 25 and m-benzyne 26 (Fig. 10).

4.1. Conundrum of the bonding in diatomic carbon.

Diatomic carbon (C2) 25, a ubiquitous intermediate, has been observed not only in interstellar space and on comets, but is also present in carbon vapor obtained from carbon arcs, candle flames, and laser desorption devices.48) 25 is also historically an elusive but extremely important chemical species that is of interest to researchers in many fields, including organic chemistry, physical chemistry, theoretical chemistry, astronomy, geology and materials science (Fig. 11). It has been long believed that the generation of C2 requires extremely high energy (e.g., vaporization of graphite requires >ca. 3500 °C) and as a result, it was the consensus that the inherent nature of 25 in the ground state is experimentally inaccessible.

In 2012, Shaik and co-workers reported a seminal theoretical study on the quadruple bonding character of 25 (Figs. 11 and 12). According to their calculation, 25 has an inverted σ bond like [1.1.1]propellane 27 and the intrinsic bonding energy of the fourth bond is in the range of 12–17 kcal mol−1. They also estimated that the electronic structure of ground-state C2 involves both a π-double-bonded (σ bond-free) structure (70.0%) and a quadruply bonded structure (13.6%) (Fig. 12).49)

This was surprising, since experimental results reported in 1970s by Skell and co-workers suggested that 25 generated by an arc discharge method exhibits dicarbene and triplet biradical characters, based on product analysis.50)–52) However, the arc discharge method potentially involves many concerns. Thus, the exposure of graphite to the arc (high temperature) should generate C1 to C4 species and their excited states in various ratios, making product analysis very complex. Therefore, a mild and selective strategy for generating C2 was highly desirable.

4.2. Room-temperature chemical synthesis of diatomic carbon.

We discovered an efficient method for the synthesis of ground-state C2 25 at room temperature/atmospheric pressure.53) Our strategy involves the fluorolysis of β-[trimethylsilyl(ethynyl)]-λ3-iodane 28 with TBAF to form anionic ethynyl-λ3-iodane 29, followed by the reductive elimination of iodobenzene (Fig. 13). The highly fluorophilic character of the silicon atom and the enhanced nucleofugality of the λ3-iodanyl group are powerful driving forces promoting the novel linear β-elimination at sp carbon. Extensive radical trapping studies with solvent, galvinoxyl free radical 30, and 9,10-dihydroanthracene 32 revealed that C2 25 generated under these conditions behaves as a moderately reactive radical (much more inert than ethynyl radical). Under the reaction conditions, 25 exhibited neither dicarbene nor triplet biradical character: notably, acetone 34, 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene 35, styrene 36, and 1,3,5-cycloheptatriene 37 –all previously reported to react with arc-generated 25– all remained completely intact (Fig. 13).54),55) These results are consistent with the idea that ground-state C2 acts as the theoretically predicted singlet biradical with quadruple bonding, thus settling a long-standing controversy between experimental and theoretical chemists.

In order to obtain more direct evidence for the generation of 25, we designed a connected flask solvent-free experiment, in which the precursor 28 and trapping agent 30 were located in separate but spatially connected flasks (Fig. 14). The fluorolysis of 28 under ambient conditions afforded the trapped product 31 (confirmed by APCI-TOFMS) in the other flask, clearly indicating the generation of gaseous 25. A 13C-labeling experiment using precursor 38 also supported the formation of free 25, as a ca. 1:1 ratio of 31-13Cα and 31-13Cβ was obtained.56) Under solvent-free conditions, we also detected larger m/z species assignable to (30)2-C4 or (30)2-C8, suggesting the formation of polyynes.53)

Various mechanisms have been proposed for the growth of carbon allotropes, involving the incorporation of C2 into a growing carbon cluster as a key step.57) However, this idea has lacked experimental verification. To evaluate whether this ground-state C2 species could act as a molecular building block for the formation of diverse carbon allotropes, we next conducted a solvent- and trapping agent-free grinding experiment using a standard agate mortar and pestle (Fig. 15A). Grinding of 28 with CsF for 10 min under an argon atmosphere resulted in the formation of a dark-brown solid containing various carbon allotropes. The ESI- and MALDI-TOF mass spectra of a toluene extract of the solid clearly showed the formation of fullerene C60. This was further supported by the observation of a peak m/z 750 assignable to C60-13C30, observed when 13C-labeled precursor 38 was used in lieu of 28 (Fig. 15B). The occurrence probability of this species in nature is extremely small [(0.01)30)]. Careful examination of the Raman spectra and high-resolution transmission electron micrograph (HRTEM) images indicated that high-quality graphite with few defects and an interlayer distance of 0.33–0.34 nm (after H2O2 treatment) and amorphous carbon (ca. 80–30% yields) had mostly been synthesized (Fig. 15C), together with a small amount of CNTs/carboncones (Fig. 15D).53) Interestingly, addition of CuCl –an alkynyl terminal stabilizer– to the optimized conditions led to a mixture of various fragments of polyynes -[C≡C]n- with different chain lengths (confirmed by MALDI-MS) (Fig. 15E). These observations support a C2-initiated growth mechanism for carbon allotropes that likely proceeds via: 1) rapid polymerization of intermediate 25 to form polyynic structures (-[C≡C]n-), followed by either 2) fusion into extended sp2-carbon frameworks such as graphene sheets and/or carbon nanotubes/carboncones, or 3) a zipper-like cyclocondensation of polyynes, as proposed by Lagow, ultimately leading to fullerene formation.58)

Ever since their existence was predicted in the early 20th century,59) benzynes 26, 39, and 40, which are reactive intermediates derived from benzene by formally removing two hydrogen atoms, have attracted broad interest among scientists (Fig. 16A).60),61) For ortho-benzyne 39, there are many well-established generation methods, such as β-elimination of a suitable precursor like ortho-(trimethylsilyl)phenyl triflate 41 (structure, Fig. 18)62) and hexadehydro-Diels-Alder reaction of ynediyne,63) and their synthetic utility has been extensively investigated.64) para-Benzyne 40 is also readily accessible by Masamune-Bergman cyclization of enediyne, and its strong biradical character has been proven to underpin the potent anticancer activity of enediyne antibiotics.65) In contrast, meta-benzyne 26 has been historically elusive for the following reasons. 1) Thermal instability: m-benzyne 26 is ca. 17 kcal/mol higher in energy than o-benzyne 39.66) 2) Limited accessibility: generation of 26 requires extremely harsh conditions such as pyrolysis of 1,3-diiodobenzene 42 (ca. 1000 °C),67) pyrolysis of isophthaloyl diacetyl peroxide 43 (300 °C),68) or detonative decomposition of 3-(carboxy)benzenediazonium salts 4469) under solvent-free conditions. 3) Complexity of electronic structure: there has been extensive debate regarding the orbital interaction between unpaired electrons in 26, and whether the interaction can be considered a through-bond/-space-stabilized singlet biradical (26-A) or an inverted σ-bond (26-B) remained to be established (Fig. 16B).70) In this context, the generation of elusive m-benzyne 26 under mild conditions (room temperature or below, in solution, atmospheric pressure) has been highly desired.

To tackle these challenges, we designed 3-(trimethylsilyl)phenyl-λ3-halogane 45 or 46 as a meta-benzyne precursor, which should undergo fluoride ion-induced γ-elimination of silyl and phenyl-λ3-haloganyl groups to afford 26 under mild conditions. Exposure of 45/46 to TBAF in the presence of the persistent radical TMPO• (TEMPO) 47 (5.0 equiv) at room temperature resulted in the formation of bis-TMPO adduct 48 (in MeCN) or mono-TMPO adduct 49 (in THF), respectively, strongly suggesting the generation of 26 (Fig. 17A).71) On the other hand, all attempts at trapping of 26 with other radical-susceptible substrates such as diphenyl disulfide 50, ethyl iodoacetate 51, and perfluoroalkyl iodide 52 were unsuccessful. These results suggest that the unpaired electrons in 26 interact with each other more strongly than in the sterically related 3D analog [3.1.1]propellane 53.72) Notably, 26 thus generated does not show electrophilicity toward fluoride ion, allowing us to investigate its reactivity as an electrophile. Fluorolysis of 45/46 in the presence of a variety of heteroatom/carbon nucleophiles revealed that 26 serves as very soft and potent electrophile: chlorobenzene 54, arylamine 55, benzonitrile 56, aryl ketone 57, and biaryl 58 were obtained in moderate to good yields (Fig. 17B). The high deuterium content (>99% D) of 54 in CD3CN suggests the intervention of the naked aryl anion, which is consistent with the reactivity trend reported for 41.73) Using Mayr and Garg’s approach, the electrophilicity of meta-benzyne 26 was also evaluated.74) Thus, a competitive experiment with amines (piperidine, N-methylpyrrolidine, benzylamine, and butylamine) revealed that the electrophilicity parameter E of meta-benzyne 26 was approximately −2, which is comparable to, but slightly smaller than, the reported value of ortho-benzyne 39 (E = −1).73) Another competitive experiment involving TMPO• 47 and piperidine provided insight into the difference of radical character between 39 and 26 (Fig. 18). Thus, ortho-benzyne 39 selectively undergoes nucleophilic addition to furnish aniline 55, whereas 26 exhibits significant reactivity toward TMPO•. This divergence appears to correlate with the difference in their biradical character (χ), as determined by CCSD(T) calculations (39: 11%; 26: 20%).66)

5. Conclusion and outlook

The introduction of hypervalent λ3-haloganyl groups –remarkable for their extraordinarily enhanced leaving group ability– into appropriate molecular frameworks has enabled us to investigate the chemical properties of previously inaccessible reactive intermediates, including carbenes, carbocations, biradicals, and inverted σ-bonded species under mild reaction conditions (ordinary temperature in solution). For instance, we successfully elucidated the chemical behavior of the highly bent cyclopent-1-enyl cation34) and the strongly electrophilic bis(triflyl)carbene (Fig. 10),75),76) neither of which could have been accessed without the λ3-bromanyl group.41),42) We anticipate that the coming decades will mark a new era in the exploration and application of reactive intermediates involving inverted σ-bonds, much like the recent resurgence in the chemistry of [1.1.1]propellane.

Our research is centered on weakly bonded reactive intermediates, particularly those featuring inverted σ-bonding, such as 1,2-/1,3-/1,4-dehydrocubanes,77) meta-benzyne cations,78) and [l.m.n]propellanes.79) We believe the insights gained from our studies will contribute to the development and broader utilization of inverted σ-bonded species in many fields, including organic synthesis, materials science and chemical biology.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by MEXT KAKENHI Grant numbers, JP24229011 (S, MU), JP17H06173 (S, MU), JP22H00320 (A, MU), JP17H03017 (B, KM), JP20H02720 (B, KM), JST CREST JPMJCR19R2 (MU), JST FOREST JPMJFR230M (KM), NAGASE Science & Technology Development Foundation (MU), Sumitomo Foundation (MU), Uehara Memorial Foundation (KM), Asahi Glass Foundation (KM), Takeda Science Foundation (KM).

The authors thank Prof. Dr. Keisuke Suzuki for his editorial advice. The authors also wish to express their sincere appreciation to Prof. Dr. Tetsuo Nagano for his unwavering warm support and encouragement throughout the course of this research and manuscript preparation.

Notes

Edited by Keisuke SUZUKI, M.J.A.

Correspondence should be addressed to: K. Miyamoto, Faculty of Pharmacy, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Keio University, 1-5-30 Shibakoen, Minato-ku, 105-8512, Japan (e-mail: miyamotokazunori@keio.jp).

References

- 1) Akiba, K.-Y. (2011) Organo Main Group Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.

- 2) Varvoglis, A. (1992) The Organic Chemistry of Polycoordinated Iodine. VCH, New York.

- 3) Zhdankin, V.V. (2014) Hypervalent Iodine Chemistry: Preparation, Structure, and Synthetic Applications of Polyvalent Iodine Compounds. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 4) Yoshimura, A. and Zhdankin, V.V. (2024) Recent progress in synthetic applications of hypervalent iodine(III) reagents. Chem. Rev. 124, 11108–11186.

- 5) Wirth, T. (ed.) (2016) Hypervalent Iodine Chemistry. Top. Curr. Chem. Vol. 373, Springer, Cham.

- 6) Wang, X. and Studer, A. (2017) Iodine(III) Reagents in Radical Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 1712–1724.

- 7) Ochiai, M. (2003) Hypervalent Iodine Chemistry (ed. Wirth, T.). Topics in Current Chemistry, Vol. 224. Springer, Cham, pp. 5–68.

- 8) Mayer, R.J., Hampel, N. and Ofial, A.R. (2021) Lewis acidic boranes, Lewis bases, and equilibrium constants: a reliable scaffold for a quantitative Lewis acidity/basicity scale. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 4070–4080.

- 9) Mayer, R.J., Ofial, A.R., Mayr, H. and Legault, C.Y. (2020) Lewis acidity scale of diaryliodonium ions toward oxygen, nitrogen, and halogen Lewis bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5221–5233.

- 10) Labattut, A., Tremblay, P.-L., Moutounet, O. and Legaults, C.Y. (2017) Experimental and theoretical quantification of the Lewis acidity of iodine(III) species. J. Org. Chem. 82, 11891–11896.

- 11) Yagupol’skii, L.M., Il’chenko, A.Y. and Kondratenko, N.V. (1974) The electronic nature of fluorine-containing substituents. Russ. Chem. Rev. 43, 32–47.

- 12) Hansch, C., Leo, A. and Taft, R.W. (1991) A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev. 91, 165–195.

- 13) Haynes, W.M. (ed.) (2011) Ionization Potentials of Atoms and Atomic Ions. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd edition). CRC Press, Boca Raton.

- 14) Okuyama, T., Takino, T., Sueda, T. and Ochiai, M. (1995) Solvolysis of cyclohexenyliodonium salt, a new precursor for the vinyl cation: remarkable nucleofugality of the phenyliodonio group and evidence for internal return from an intimate ion-molecule pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 3360–3367.

- 15) Okuyama, T. and Fujita, M. (2005) Generation of cycloalkynes by hydro-iodonio-elimination of vinyl iodonium salts. Acc. Chem. Res. 38, 679–686.

- 16) Kitamura, T., Kotani, M., Yokoyama, T., Fujiwara, Y. and Hori, K. (1999) A new hypervalent iodine precursor of a highly strained cyclic alkyne. Generation and trapping reactions of bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-en-5-yne. J. Org. Chem. 64, 680–681.

- 17) Kitamura, T. (2010) Synthetic methods for the generation and preparative application of benzyne. Aust. J. Chem. 63, 987–1001.

- 18) Ochiai, M., Tsuchimoto, Y. and Hayashi, T. (2003) Borane-induced radical reduction of 1-alkenyl- and 1-alkynyl-λ3-iodanes with tetrahydrofuran. Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 5381–5384.

- 19) Ochiai, M., Kunishima, M., Tani, S. and Nagao, Y. (1991) Generation of [β-(phenylsulfonyl)alkylidene]carbenes from hypervalent alkenyl- and alkynyliodonium tetrafluoroborates and synthesis of 1-(phenylsulfonyl)cyclopentenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 3135–3142.

- 20) Hadjiarapoglou, L., Spyroudis, S. and Varvoglis, A. (1985) Phenyliodonium bis(phenylsulfonyl)methylide, a new hypervalent iodonium ylide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107, 7178–7179.

- 21) Winterson, B., Patra, T. and Wirth, T. (2022) Hypervalent bromine(III) compounds: Synthesis, applications, prospects. Synthesis 54, 1261–1271.

- 22) Huheey, J.E., Keiter, E.A. and Keiter, R.L. (1993) Inorganic Chemistry—Principles of Structure and Reactivity. 4th ed. Hapere Collins, New York.

- 23) Lide, D.R. (ed.) (1992) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 24) Nguyen, T.T. and Martin, J.C. (1980) A dialkoxyarylbrominane. The first example of an organic 10-Br-3 species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 7382–7383.

- 25) Sokolovs, I. and Suna, E. (2023) Electrochemical synthesis of dimeric λ3-bromane: platform for hypervalent bromine(III) compounds. Org. Lett. 25, 2047–2052.

- 26) Nesmeyanov, A.N., Tolstaya, T.P. and Isaeva, L.S. (1955) Diphenylbromonium salts. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 104, 872–875.

- 27) Janulis, E.P. Jr. and Arduengo, A.J. III (1983) Diazotetrakis(trifluoromethyl)cyclopentadiene and ylides of electronegative elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 3563–3567.

- 28) Nesmeyanov, A.N., Vanchikov, A.N., Lisichkina, I.N., Lazarev, V.V. and Tolstaya, T.P. (1980) Diarylbromonium salts from bromine trifluoride and symmetric aromatic mercury compounds. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 255, 1136.

- 29) Miyamoto, K. (2018) Chemistry of hypervalent bromine. In Patai’s Chemistry of Functional Groups (ed. Rappoport, Z.). John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

- 30) Frohn, H.J. and Giesen, M. (1984) Beitrage zur chemie des bromtrifluorids 1. Teil pentafluorphenylbrom(III)difluorid und -bis(trifluoracetat). J. Fluor. Chem. 24, 9–15.

- 31) Ochiai, M. (2009) Hypervalent aryl-, alkynyl-, and alkenyl-λ3-bromanes. Synlett 2009, 159–173.

- 32) Ochiai, M., Nishi, Y., Goto, S., Shiro, M. and Frohn, H.J. (2003) Synthesis, structure, and reaction of 1-alkynyl(aryl)-λ3-bromanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 15304–15305.

- 33) Ochiai, M., Okubo, T. and Miyamoto, K. (2011) Weakly nucleophilic conjugate bases of superacids as powerful nucleophiles in vinylic bimolecular nucleophilic substitutions of simple β-alkylvinyl(aryl)-λ3-bromanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 3342–3343.

- 34) Miyamoto, K., Shiro, M. and Ochiai, M. (2009) Facile generation of a strained cyclic vinyl cation by thermal solvolysis of cyclopent-1-enyl-λ3-bromanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 8931–8934.

- 35) Ochiai, M., Tada, N., Murai, K., Goto, S. and Shiro, M. (2006) Synthesis and characterization of bromonium ylides and their unusual ligand transfer reactions with N-heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 9608–9609.

- 36) Ochiai, M., Kaneaki, T., Tada, N., Tada, N., Miyamoto, K., Chuman, H. et al. (2007) A new type of imido group donor: synthesis and characterization of sulfonylimino-λ3-bromane that acts as a nitrenoid in the aziridination of olefins at room temperature under metal-free conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12938–12939.

- 37) Ochiai, M., Okada, T., Tada, N., Yoshimura, A., Miyamoto, K. and Shiro, M. (2009) Difluoro-λ3-bromane-induced Hofmann rearrangement of sulfonamides: synthesis of sulfamoyl fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8392–8393.

- 38) Ochiai, M., Yoshimura, A., Miyamoto, K., Hayashi, S. and Nakanishi, W. (2010) Hypervalent λ3-bromane strategy for Baeyer-Villiger oxidation: selective transformation of primary aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes to formates, which is missing in the classical Baeyer-Villiger oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 9236–9239.

- 39) Ochiai, M., Miyamoto, K., Kaneaki, T., Hayashi, S. and Nakanishi, W. (2011) Highly regioselective amination of unactivated alkanes by hypervalent sulfonylimino-λ3-bromane. Science 332, 448–451.

- 40) Grushin, V.V., Demkina, I.I., Tolstaya, T.P., Galakhov, M.V. and Bakhmutov, V.I. (1989) The electronic effects of phenylhalogenonium and 9-m-carboranylhalogenonium groups. Nucleophilic substitution in halogenonium salts of the carbaborane and aromatic series. Organomet. Chem. USSR 2, 373–378.

- 41) Miyamoto, K. (2014) Synthesis of hypervalent organo-λ3-bromanes and their reactions by using leaving group ability of λ3-bromanyl group. Yakugaku Zasshi 134, 1287–1300 (in Japanese).

- 42) Miyamoto, K., Uchiyama, M. and Ochiai, M. (2023) Synthesis, characterization, and reaction of hypervalent organo-λ3-bromanes and chloranes. Yuki Gosei Kagaku Kyokaishi 81, 416–427 (in Japanese).

- 43) Nesmeyanov, A.N. and Tolstaya, T.P. (1955) Diphenylchloronium salts. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 105, 94–95.

- 44) Olah, G.A., Sakakibara, T. and Asensio, G. (1978) Onium ions. 17. Improved preparation, carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance structural study, and nucleophilic nitrolysis (Nitrative Cleavage) of diarylhalonium ions. J. Org. Chem. 43, 463–468.

- 45) Nakajima, M., Miyamoto, K., Hirano, K. and Uchiyama, M. (2019) Diaryl-λ3-chloranes: versatile synthesis and unique reactivity as aryl cation equivalent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6499–6503.

- 46) Littke, A.F. and Fu, G.C. (2002) Palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions of aryl chlorides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 4176–4211.

- 47) Ingold, C.K. (1934) Principles of an electronic theory of organic reactions. Chem. Rev. 15, 225–274.

- 48) Hofmann, R. (1995) Marginalia: C2 in all its guises. Am. Sci. 83, 309–311.

- 49) Shaik, S., Danovich, D., Wu, W., Su, P., Rzepa, H.S. and Hiberty, P.C. (2012) Quadruple bonding in C2 and analogous eight-valence electron species. Nat. Chem. 4, 195–199.

- 50) Shaik, S., Danovich, D., Braida, B. and Hiberty, P.C. (2016) The quadruple bonding in C2 reproduces the properties of the molecule. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 4116–4128.

- 51) Skell, P.S., Havel, J.J. and McGlinchey, M.J. (1973) Chemistry and the carbon arc. Acc. Chem. Res. 6, 97–105.

- 52) Skell, P.S. and Plonka, J.H. (1970) Chemistry of the singlet and triplet C2 molecules. Mechanism of acetylene formation from reaction with acetone and acetaldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 5620–5624.

- 53) Miyamoto, K., Narita, S., Masumoto, Y., Hashishin, T., Osawa, T., Kimura, M. et al. (2020) Room-temperature chemical synthesis of C2. Nat. Commun. 11, 2134.

- 54) Pan, W. and Shevlin, P.B. (1996) Reaction of atomic and molecular carbon with cyclooctatetraene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 10004–10005.

- 55) Pan, W., Armstrong, B.M., Shevlin, P.B., Crittell, C.H. and Stang, P.J. (1999) A potential chemical source of C2. Chem. Lett. 28, 849.

- 56) Miyamoto, K., Narita, S., Masumoto, Y., Hashishin, T., Osawa, T., Kimura, M. et al. (2021) Reply to “A thermodynamic assessment of the reported room-temperature chemical synthesis of C2”. Nat. Commun. 11, 1245.

- 57) Irle, S., Zheng, G., Wang, Z. and Morokuma, K. (2006) The C60 formation puzzle “solved”: QM/MD simulations reveal the shrinking hot giant road of the dynamic fullerene self-assembly mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 14531–14545.

- 58) Lagow, R.J., Kampa, J.J., Wei, H.-C., Battle, S.L., Genge, J.W., Laude, D.A. et al. (1995) Synthesis of linear acetylenic carbon: the “sp” carbon allotrope. Science 267, 362–367.

- 59) Kim, N., Choi, M., Suh, S.-E. and Chenoweth, D.M. (2024) Aryne chemistry: generation methods and reactions incorporating multiple arynes. Chem. Rev. 124, 11435–11522.

- 60) Wentrup, C. (2010) The benzyne story. Aust. J. Chem. 63, 979–986.

- 61) Wenk, H.H., Winkler, M. and Sander, W. (2003) One century of aryne chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 502–528.

- 62) Shi, J., Li, L. and Li, Y. (2021) o-Silylaryl triflates: a journey of Kobayashi aryne precursors. Chem. Rev. 121, 3892–4044.

- 63) Fluegel, L.L. and Hoye, T.R. (2021) Hexadehydro-Diels–Alder reaction: benzyne generation via cycloisomerization of tethered triynes. Chem. Rev. 121, 2413–2444.

- 64) Hoffmann, R.W. and Suzuki, K. (2013) A “hot, energized” benzyne. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2655–2656.

- 65) Sander, W. (1999) m-Benzyne and p-benzyne. Acc. Chem. Res. 32, 669–676.

- 66) Kraka, E. and Cremer, D. (1993) Ortho-, meta-, and para-benzyne. A comparative CCSD (T) investigation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 216, 333–340.

- 67) Fisher, I.P. and Lossing, F.P. (1963) Ionization potential of benzyne. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 1018–1019.

- 68) Sander, W., Exner, M., Winkler, M., Balster, A., Hjerpe, A., Kraka, E. et al. (2002) Vibrational spectrum of m-benzyne: a matrix isolation and computational study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13072–13079.

- 69) Berry, R.S., Clardy, J. and Schafer, M.E. (1965) Decomposition of benzenediazonium-3-carboxylate: transient 1,3-dehydrobenzene. Tetrahedron Lett. 6, 1011–1017.

- 70) Winkler, M. and Sander, W. (2001) The structure of meta-benzyne revisited — a close look into σ-bond formation. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 10422–10432.

- 71) Koyamada, K., Miyamoto, K. and Uchiyama, M. (2024) Room-temperature synthesis of m-benzyne. Nat. Synth. 3, 1083–1090.

- 72) Iida, T., Kanazawa, J., Matsunaga, T., Miyamoto, K., Hirano, K. and Uchiyama, M. (2022) Practical and facile access to bicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes: potent bioisosteres of meta-substituted benzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21848–21852.

- 73) Perrin, C.L. and Reyes-Rodríguez, G.J. (2014) Selectivity and isotope effects in hydronation of a naked aryl anion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15263–15269.

- 74) Nathel, N.F.F., Morrill, L.A., Mayr, H. and Garg, N.K. (2016) Quantification of the electrophilicity of benzyne and related intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10402–10405.

- 75) Miyamoto, K., Iwasaki, S., Doi, R., Ota, T., Kawano, Y., Yamashita, J. et al. (2016) Mechanistic studies on the generation and properties of super-electrophilic singlet carbenes from bis(perfluoroalkanesulfonyl)bromonium ylides. J. Org. Chem. 81, 3188–3198.

- 76) Ochiai, M., Tada, N., Okada, T., Sota, A. and Miyamoto, K. (2008) Thermal and catalytic transylidations between halonium ylides and synthesis and reaction of stable aliphatic chloronium ylides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 2118–2119.

- 77) Hrovat, D.A. and Borden, W.T. (1990) Ab initio calculations of the relative energies of 1,2-, 1,3-, and 1,4-dehydrocubane: prediction of dominant through-bond interaction in 1,4-dehydrocubane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 875–876.

- 78) Schleyer, P.v.R., Jiao, H., Glukhovtsev, M.N., Chandrasekhar, J. and Krakas, E. (1994) Double aromaticity in the 3,5-dehydrophenyl cation and in cyclo[6]carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 10129–10134.

- 79) Dilmaç, A.M., Spuling, E., de Meijere, A. and Bräse, S. (2017) Propellanes—from a chemical curiosity to “explosive” materials and natural products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5684–5718.

Non-standard abbreviation list

Mesmesityl

TBAFtetra-n-butylammonium fluoride

TMPO2,2,4,4-tetramethylpiperidine 1-oxyl

Profile

Kazunori Miyamoto was born in Tokushima in 1979 in Tokushima Prefecture, Japan. After graduating from the University of Tokushima, he proceeded to study main group organic chemistry under the supervision of Professor Masahito Ochiai at the University of Tokushima and received his MSc (2004) and Ph.D. (2008) degrees from University of Tokushima. He was appointed Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Tokushima, in 2005. He moved to the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of Tokyo, as a Lecturer in 2014 and was promoted to Associate Professor in 2019. He moved to Faculty of Pharmacy, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Keio University as Professor in 2024. His research interests include hypervalent halogen compounds and the development of organic reactions based on the unique characteristics of these compounds. He is a recipient of the SSOCJ Research Planning Award (2010), The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan Award for Young Scientists (2014), Chemist Award BCA (2018), and MEXT Young Scientists’ Prize (2019).

Masanobu Uchiyama was born in Saitama in 1969 in Saitama Prefecture, Japan. He received his Ph.D. degree in 1998 from The University of Tokyo. He was appointed as Assistant Professor at the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tohoku University, in 1995. He moved to the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, The University of Tokyo, as Assistant Professor in 2001 and was promoted to Lecturer in 2003. He moved to RIKEN as Associate Chief Scientist (PI) in 2006. He has been Professor at The University of Tokyo since 2010. He was promoted to Chief Scientist at RIKEN in 2013 (Joint Appointment, 2013–2021), and is also Professor of the Research Initiative for Supra-Materials (RISM) at Shinshu University (Cross Appointment, 2020–2025). He has received the Banyu Young Chemist Award (1999), The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan Award for Young Scientists (2001), 2001 SYNTHESIS-SYNLETT-Journals Award (2001), Inoue Research Award for Young Scientists (2002), Incentive Award in Synthetic Organic Chemistry, Japan (2006), MEXT Young Scientists’ Prize (2009), SSOCJ Nissan Chemical Industries Award for Novel Reaction & Method (2014), and Seiichi Tejima Research Award (2015).

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1423-6287

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1423-6287

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6385-5944

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6385-5944