2014 Volume 90 Issue 1 Pages 1-11

2014 Volume 90 Issue 1 Pages 1-11

Borylated functional π-systems are useful building blocks to enable efficient synthesis of novel molecular architectures with beautiful structures, intriguing properties and unique functions. Introduction of boronic ester substituents to a variety of extended π-systems can be achieved through either iridium-catalyzed direct C–H borylation or the two-step procedure via electrophilic halogenation followed by palladium-catalyzed borylation. This review article focuses on our recent progress on borylation of large π-conjugated systems such as porphyrins, perylene bisimides, hexabenzocoronenes and dipyrrins.

Functional π-systems have gained its importance as organic optelectronic materials as well as the classical but widespread use in dyes and pigments.1) Prospective application of functional π-systems covers a whole range of organic materials for OFET (organic field effect transistors), OLED (organic light-emitting diodes), OPV (organic photovoltaic cells), non-linear optics, biosensors, optical memory and so forth. To obtain desirable properties such as optical and electronic characters as well as stability, solubility and morphology of materials, introduction of appropriate substituents to the periphery of π-systems is often essential. This kind of modification of π-systems has been achieved through conventional electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions such as Friedel–Crafts reactions. However, these classical methodologies generally require rather harsh reaction conditions, which are sometimes incompatible with reactive functional groups. Moreover, regioselectivity of these electrophilic reactions generally controlled by the intrinsic electronic factor of the individual π-conjugated system, resulting in difficulty to attain different types of regiocontrol.

Recently, direct functionalization through C–H bond cleavage with transition metal complexes has proven to be powerful tools for regioselective modification of aromatic compounds.2) Among such a type of reactions, iridium-catalyzed direct C–H borylation of aromatic compounds developed by Smith, Hartwig, Ishiyama and Miyaura has emerged as an efficient route to organoboron compounds.3),4) A dioxaborolanyl group can be efficiently introduced to aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds under very mild reaction conditions (Scheme 1). This reaction is not only interesting in light of its reaction mechanism involving an efficient C–H cleavage process, but also provides organoboranes which are otherwise difficult to prepare by conventional methods, clearly demonstrating the power of transition metal catalysis in organic synthesis.

As a further extension of this strategy, Miyaura, Ishiyama and coworkers have reported iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation of benzoate esters and aryl ketones with electron-deficient phosphine ligands (Scheme 2).5) This protocol allows regioselective introduction of a boryl substituent at the ortho position to the carbonyl group on aromatic rings.

In addition, aromatic boronic esters can be conveniently prepared through palladium-catalyzed borylation of aryl halides with the diboron reagent (Scheme 3).6) When aryl halides are readily available, this protocol is often quite effective to access functionalized aryl- and heteroarylboronic esters. Importantly, iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation reaction often exhibits different regioselectivity from electrophilic halogenation of aromatic systems, since the steric factor of substrates mainly dominates iridium-catalyzed borylation. In contrast, regioselectivity of halogenation is controlled by the electronic factor via electrophilic substitution. Consequently, iridium-catalyzed direct borylation and palladium-catalyzed borylation are often complementary. This feature is beneficial to fabricate functional π-systems with substituents at a variety of positions.

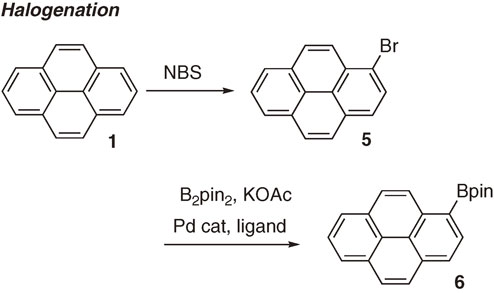

After unique reactivity and selectivity were elucidated with substituted benzenes and heteroaromatics, the direct borylation has been applied to extended π-conjugated molecules. C–H borylation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons was reported by Marder et al. in 2005 (Scheme 4).7) They disclosed highly regioselective direct C–H borylation of naphthalene, pyrene 1 and perylene 3 by the [Ir(OMe)cod]2/dtbpy catalyst combination. The interesting feature of this transformation is specific regioselectivity, which is quite different from the conventional electrophilic halogenation to afford 1-bromopyrene 5 (Scheme 5). Now one can access both type of derivatives by the proper choice of functionalization methods.

Kobayashi and coworkers further extended this protocol to oligoacenes such as antracene and tetracene.8) Direct borylation of tetracene 7 provided a 1:1 mixture of 2,8- and 2,9-diborylated tetracenes 8 and 9 (Scheme 6). Borylated tetracenes were useful building blocks for π-conjugated tetracenes for OFET application. Isobe also reported iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation of phenacene.9)

In 2012, Scott et al. found that the addition of a small amount of potassium tert-butoxide in the borylation facilitates equilibrium of the kinetic products to more thermodynamically stable borylated products. With an excess amount of borylating agent (B2pin2) and a catalytic amount of t-BuOK, 1,3,5,7,9-pentaborylated corannulene 11 was obtained in excellent yield through direct borylation of corannulene 10 (Scheme 7).10)

Iridium-catalyzed direct borylation also proceeded on azulene, which is a representative nonbenzenoid aromatic hydrocarbon. Murafuji and Sugihara reported C–H borylation of azulene 12 to afford a mixture of 2- and 1-borylated azulenes 13 and 14 in 70% and 10% yields, respectively (Scheme 8).11)

Porphyrins are one of the most important functional molecules, which are planar polypyrrole macrocycle with an 18π distinct aromatic character.12) This molecule has its long history of extensive researches covering a wide field of natural sciences. The material science related to porphyrin includes artificial photosynthesis, organic solar cells, photodynamic therapy, light-emitting materials, near-infrared dyes, non-linear optical materials, molecular wires, catalysis, supramolecules and so forth.

However, functionalization of porphyrin derivatives had been limited to electrophilic substitution such as halogenation, nitration and formylation, which proceed selectively at the meso-positions in the case of meso-unsubstituted porphyrins such as 15 (Scheme 9). We envisioned the potential of transition metal-catalyzed direct C–H functionalization of porphyrins because porphyrins have several aromatic Csp2–H bonds. This rather naive idea led us to attempt iridium-catalyzed direct borylation of triarylporphyrins 15, which actually took place efficiently and regioselectively to provide borylated porphyrins 17 in good to excellent yields (Scheme 10).13) Borylation proceeded exclusively at the β-positions. Importantly, this type of regioselectivity had never been accomplished by the conventional electrophilic substitution reactions.14)

Borylated porphyrins are quite useful building blocks for the synthesis of novel and exotic porphyrin derivatives,15) which are otherwise difficult to access by the conventional porphyrin synthesis. Borylated porphyrins were employed for preparing porphyrin oligomers16) with unique shapes and interesting optical properties, highly conjugated porphyrins17) for dye-sensitized solar cell application, cyclometallated porphyrins,18) cyclophane-like diporphyrins19) and so forth. For example, tetraborylated porphyrin 18 is a key intermediate for construction of a porphyrin tube 20 (Scheme 11).20)

In the case of 5,10,15,20-tetraarylporphyrins, iridium-catalyzed borylation does not take place on the porphyrin skeleton. The aryl substituents instead of the porphyrin core can be selectively borylated.21) For example, porphyrin tetramer 21 can be borylated exclusively on the methoxyphenyl groups to provide diborylated product 22 because 21 has accessible C–H bonds only on the terminal aryl substituents (Scheme 12). This procedure would be useful for terminal selective functionalization of molecular wires.

Corrole is a representative porphyrin analogue with one direct pyrrole–pyrrole linkage.22) Corrole is also 18π aromatic molecule that exhibits interesting optical properties and unique metal coordination chemistry. However, the synthesis of corrole derivatives remains rather limited due to lack of regioselective functionalization of corroles. On the basis of iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation, we achieved highly regioselective synthesis of 2-borylated corrole 24,23) which turned out to be a useful platform for functionalization of corroles (Scheme 13).

On the basis of regioselective C–H borylation of corrole 23, we synthesized and characterized singly and doubly linked corrole dimers 25 and 26 (Scheme 14). The corrole dimer 26 exhibits very broad absorption bands, which reach to 1700 nm because of its substantial biradical character.24)

Expanded porphyrins are porphyrin-like π-conjugated macrocyclic molecules with more than four pyrrole units.25) Aromatic substituents on expanded porphyrins such as hexaphyrin can be also borylated. In this case, borylation occurred on 28π-hexaphyrin 27 but not on 26π-hexaphyrin 29 probably because of oxidative nature of 29 (Scheme 15).26)

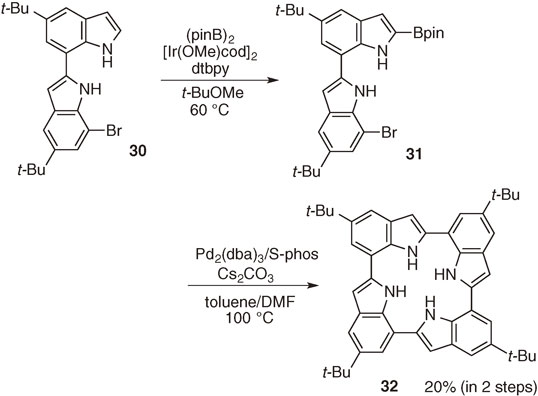

Direct C–H borylation is also useful for the preparation of the intermediate to a porphyrin-like cyclic tetraindole 32.27) The synthesis of cyclic tetraindole 32, which has a similar structure to the porphyrin system, had been quite difficult by conventional method due to steric repulsion of inner four NH protons in the central cavity. We accomplished preparation of this molecule through direct borylation of bisindole 30 as the key step. Iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation of bisindole 30 provided borylated indole 31 in almost quantitative yield. Dimerization of 31 under the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling conditions provided cyclic tetraindole 32 in 20% yield (Scheme 16).

The highly distorted structure of cyclic tetraindole 32 was elucidated on the basis of X-ray crystallographic analysis. In addition, 32 was unstable under air. We then found that tetraindole 32 can be oxidized into a highly planar macrocycle 33 through oxidation with bromine (Scheme 17). The oxidized macrocycle 34 can capture metal ions such as Cu(II), Zn(II) and Ni(II) in its porphyrin-like inner cavity. The metalated macrocycles 34 exhibited the broad and wide absorption band, which covered over the visible region.

Perylene tetracarboxylic acid bisimide (35, PBI) is an important class of dyes and pigments for widespread use.28) Recently, PBI derivatives have received much attention for applications toward organic optelectronic materials. The conventional synthesis of PBI derivatives employs halogenation at the bay area (1,6,7,12-positions) to furnish halogenated PBIs such as 36 (Scheme 18).29) This is due to the high reactivity of the bay area toward electrophilic substitutions. Regioselective functionalization at 2,5,8,11-positions of PBIs had been unavailable until our reports on direct alkylation and arylation of PBIs at 2,5,8,11-positions by Murai–Chatani–Kakiuchi reaction (Scheme 19).30)

We also accomplished regioselective four-fold C–H borylation of PBI 35 with a [Ir(OMe)cod]2/(C6F5)3P catalyst system (Scheme 20).31),32) The boron substituents in borylated PBI 39 can be oxidized to hydroxy groups with hydroxylamine. Interestingly, introduction of the hydroxy group 2,5,8,11-positions induced substantial blue-shift in the UV/vis absorption spectrum due to intramolecular hydrogen bonding interactions. In addition, borylated PBIs 39 serve as a building block for molecular assemblies on the basis of PBI though palladium-catalyzed cross coupling reaction.33) The substitutions at 2,5,8,11-positions maintain planar geometry of the perylene π-plane while the conventional modification at the bay areas generally induce molecular distortion due to steric repulsion between substituents.

Hexa-peri-hexabenzocoronene (HBC) has attracted much attention as a fragment of graphene.34) The edge structure of graphene results in significant changes its physical property. Consequently, effective functionalization of HBCs is needed to access model compounds for functionalized graphenes.

We demonstrated that iridium-catalyzed direct borylation of substituted HBC 41 proceeded efficiently to furnish borylated HBC 42 in good yield (Scheme 21).35) The borylated HBC 42 was successfully converted into hydroxy HBC 43, which is difficult to prepare by the conventional HBC synthesis. In addition, π-extended quinone 44 was synthesized for the first time through oxidation of dihydroxy HBC 43.

Borylation of HBCs allows efficient installation of various functionalities after construction of the HBC skeleton.36) The boryl groups in borylated HBC 45 can be transformed to triflate groups, which are versatile intermediate for further functionalization (Scheme 22).

Boron dipyrrin (BODIPY) is also an important class of π-systems, which has wide-spread application in labeling reagents, fluorescent switches, chemosensors, near IR absorbing/emitting dyes and dyes-sensitized solar cells owing to their advantageous photophysical properties such as photostability, high absorption coefficients and high fluorescence quantum yields.37) Functionalization of BODIPY dyes is important for fine-tuning of the spectroscopic and electronic properties.

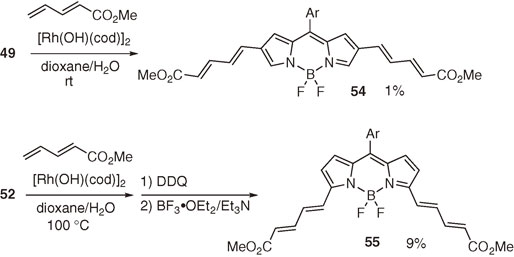

We applied iridium-catalyzed direct borylation to BODIPY dye 48 and dipyrromethane 51 (Scheme 23).38) We demonstrated that borylation was highly regioselective and complementary. C–H borylation occurs exclusively at the α-position for dipyrromethane 51 and at the β-positions for BODIPY 48. This regioselectivity allows synthesis of a variety of α- and β-substituted BODIPY dyes. The introduction of unsaturated ester moieties to BODIPY was achieved through rhodium-catalyzed Heck-type addition (Scheme 24).

β-Borylated BODIPY 50 was also prepared through palladium-catalyzed borylation of bromo BODIPY 56, which was obtained by regioselective bromination of BODIPY 48 with N-bromosuccinimide (Scheme 25).39) Although this protocol required two reaction steps, the total yields were better than those via iridium-catalyzed direct borylation, as shown in Scheme 23. Borylated BODIPY 50 was employed for the efficient construction of linear BODIPY dimer and trimer 58, which exhibit strong absorption and emission in near IR region (Scheme 26).

The use of organic molecules for electronic devise has come into reality. In our daily life, we rely on smart phones and tablets, into which functional organic materials are fabricated. It is quite sure that organic materials would further substitute inorganic materials in many ways during this century. To support this shift, synthesis of the organic materials should be more efficient, cost-effective and environmentally benign. Direct C–H functionalization should be the key technology to enable the straightforward preparation of organic π-conjugated molecules with excellent optical and electronic functions. In this sense, C–H borylation is not still ideal since the boron group is not incorporated in the final products and is wasted during the synthesis. Synthetic organic chemists should devote their efforts more to achieve the ideal synthesis of organic functional materials.

Hiroshi Shinokubo was born in Kyoto in 1969. He received his B.Eng in 1992 and Ph.D. in 1998 from Kyoto University under the guidance of Profs. Kiitiro Utimoto and Koichiro Oshima. He became Assistant Professor in 1995, at Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University, working for Prof. Oshima. He worked with Prof. Rick L. Danheiser at MIT from 1999 to 2000 as a visiting scientist. He then collaborated with Prof. Atsuhiro Osuka at Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, as Associate Professor from 2003 to 2008. He was also selected as a PRESTO researcher at Japan Science and Technology Agency from 2003 to 2007. In 2008, he became Professor at Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University. He received the Chemical Society of Japan Award for Young Chemists in 2004, the Minister Award for Distinguished Young Scientists from MEXT in 2008, the JSPS Prize in 2012 and SSOCJ DIC Award for Functional Material Chemistry 2013. He is exploring efficient syntheses of novel organic molecules, which have fascinating structures, properties and functions. His current targets include new porphyrin analogues and large polyaromatic molecules.

I am deeply indebted to all of my colleagues for their enthusiastic contributions and efforts. These works were supported by grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from MEXT, Japan. I am also grateful for the PRESTO project at Japan Science and Technology Agency.