2023 Volume 99 Issue 3 Pages 75-101

2023 Volume 99 Issue 3 Pages 75-101

L-DOPA is an amino acid that is used as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease. A simple enzymatic synthesis method of L-DOPA had been developed using bacterial L-tyrosine phenol-lyase (Tpl). This review describes research on screening of bacterial strains, culture conditions, properties of the enzyme, reaction mechanism of the enzyme, and the reaction conditions for the production of L-DOPA. Furthermore, molecular bleeding of constitutively Tpl-overproducing strains is described, which were developed based on mutations in a DNA binding protein, TyrR, which controls the induction of tpl gene expression.

Tyrosine (Tyr) phenol-lyase (Tpl, EC4.1.99.2) is an enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of L-tyrosine (L-Tyr) into phenol, pyruvate, and ammonia (Reaction a) in Scheme 1). This enzyme was first found by Kakihara et al. in 1953 in an intestinal bacterium, named Bacterium coli phenologenes, as an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of phenol from L-Tyr.1) This enzyme was initially named as β-tyrosinase, because it catalyzes primary fission of the side chain of L-Tyr at the β-carbon position. They also reported that this enzyme was induced by the addition of L-Tyr into the culture medium and found that it was activated by the addition of pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) with partially purified enzyme preparation.2),3) A similar enzymatic reaction was described by Brot et al. with a partially purified enzyme preparation from Clostridium tetanomorphum in 1965.4)

Reactions catalyzed by tyrosine phenol-lyase.

A homogeneous crystalline preparation of Tpl was obtained by Yamada et al. in 1968 from Escherichia intermedia,5) and enzymatic properties including cofactor requirement were reported by Kumagai et al.6),7) During the course of investigation of the catalytic properties of Tpl, this enzyme was found to be a so-called multifunctional enzyme because it catalyzed β-replacement reaction (Reaction b) in Scheme 1)8) and racemization reaction (Reaction d) in Scheme 1)9) besides α,β-elimination reaction (Reaction a) in Scheme 1). The finding of the 3,4-dihydroxy-phenyl-L-alanine (L-DOPA) synthesis reaction by β-replacement reaction of Tpl accelerated research on the industrial production of L-DOPA, which is a useful amino acid for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. In this disease, the amount of dopamine that is working as a neurotransmitter is insufficient in the brain of the patient. Medication with dopamine is not effective, because it cannot pass through the blood–brain barrier present at the entrance of the brain. However, L-DOPA can pass through the blood–brain barrier and is changed to dopamine by a decarboxylation reaction in the brain.

Commercially, L-DOPA is produced mainly by a chemical synthetic method that contains eight reaction steps, including a step for optical resolution. Enzymatic synthesis of L-DOPA is expected to provide a much more economical and simpler one-step method for L-DOPA production. Collaborative research between Yamada’s Laboratory in Research Institute for Food Science, Kyoto University and Central Research Laboratories in Ajinomoto Co., Inc., Kawasaki, Japan started with screening of a microbial strain that had high Tpl activity for the production of L-DOPA from D,L-serine (Ser) and pyrocatechol by β-replacement reaction (Scheme 1) with intact cells of microorganisms cultivated in medium containing L-Tyr. A bacterial strain Erwinia herbicola that showed the highest activity of all 1,038 microorganism strains tested was selected as a promising strain for the production of L-DOPA.10) Then, the culture conditions to obtain high Tpl activity11) and the reaction conditions to obtain a good yield of L-DOPA12) were extensively investigated with intact cells of this E. herbicola strain and a number of effective experimental results were obtained.13) A remarkable finding was that Tpl can catalyze a reverse reaction of α,β-elimination, in which L-DOPA was produced from pyruvate, ammonium, and pyrocatechol (Reaction c) in Scheme 1).14) This reverse reaction, which was completely unexpected before, was also confirmed with purified Tpl of E. intermedia.15) The reaction conditions to produce L-DOPA from pyruvate, ammonia, and pyrocatechol were determined.16) The practical industrial production of L-DOPA by this synthesis reaction from pyruvate, ammonium, and pyrocatechol started in 1992 in Ajinomoto Co., Inc. with the cells of E. herbicola having extensively high activity of Tpl.

As the start of genetic studies on Tpl, cloning and sequencing of Tpl genes (tpl) from Citrobacter freundii,17) E. intermedia,18) E. herbicola,19) and Symbiobacterium thermophilum were reported.20) We examined the induction and repression of Tpl of E. herbicola at the transcriptional level and showed that the transcription of tpl was increased by the addition of L-Tyr and decreased by the addition of glucose in the medium.21) Analysis of the 5′-flanking region of E. herbicola tpl gene suggested the existence of consensus sequences of a regulatory protein, TyrR, binding box.21),22) TyrR is known as a regulator of the genes encoding proteins responsible for the biosynthesis and transport of aromatic amino acids23),24) in E. coli. Analysis of the mechanism of regulation of tpl expression was of interest because Tpl had been known as an amino acid degrading enzyme physiologically. Such analysis of the E. herbicola tpl gene was also valuable for increasing Tpl activity in bacterial cells to contribute to more-effective production of L-DOPA.

Investigations of the mechanism of regulation of tpl was performed by Smith and Somerville25) and Bai and Somerville26) in C. freundii, and the results suggested that the tpl promotor is subject to activation by TyrR. Subsequently, Katayama et al. reported the transcriptional regulation of tpl mediated through TyrR and cAMP receptor protein in E. herbicola.22) Based on these results, we cloned the tyrR gene of E. herbicola and then randomly mutagenized it to create a high-Tpl-expressing strain. The resultant strain expressed tpl without the addition of L-Tyr to the medium and produced as much Tpl as the wild-type (WT) strain grown in L-Tyr-induced conditions.27) Furthermore, we found that ligand-mediated oligomer formation of TyrR, which is required for tpl activation was drastically enhanced by an amino acid substitution at N324 in E. herbicola TyrR (EhTyrR) and at the corresponding N316 in E. coli TyrR (EcTyrR).28) Then, we constructed a gene with various combinations of newly found mutations and previously obtained ones and introduced the resulting mutant tyrR genes into E. herbicola to develop an L-DOPA hyper-producer strain that possessed constitutively producing ability of Tpl without the addition of L-Tyr to the culture medium.29)

This review is a summary of basic and applied research on L-DOPA production by bacterial Tpl.

Tpl was first found in a bacterial strain named B. coli phenologenes, isolated from human feces.1) Then it was reported in C. tetanomorphum.4) The occurrence of Tpl activity in bacteria was also investigated using the type culture collection of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.30) Of 38 strains tested, six strains mainly belonging to Enterobacteriaceae showed activity of an α,β-elimination reaction to degrade L-Tyr into phenol, pyruvate, and ammonia (Scheme 1). The strain that showed the strongest activity of the six strains was E. intermedia (this strain’s name was taxonomically changed later to Citrobacter intermedius). Homogeneous preparation of Tpl was obtained for the first time from E. intermedia,5) and its properties6),7) including the catalysis of β-replacement reaction (Scheme 1) to produce L-DOPA8) were reported.

In an investigation for the industrial production of L-DOPA, large-scale screening was conducted with 1,038 strains of microorganisms; 760 strains of bacteria, including 117 strains of actinomycetes, 140 strains of yeasts, and 138 strains of fungi mainly from the type culture collection of Central Research Laboratories of Ajinomoto Co., Inc. and also with 1,420 bacterial strains obtained from natural sources. In this screening, β-replacement reaction activities to produce L-Tyr or L-DOPA from D,L-Ser and phenol or pyrocatechol were measured using intact microbial cells cultured on agar-slants with medium containing L-Tyr.10) Activity was widely distributed in various strains of bacteria, especially in the genera Escherichia, Proteus, and Erwinia as shown in Table 1. No activity was detected in actinomycetes, yeast, or fungi. Higher activities of L-Tyr and L-DOPA synthesis were detected in E. coli, E. freundii (this strain’s name was taxonomically changed later to C. freundii), E. intermedia, Proteus morganii, and E. herbicola (this strain’s name was taxonomically changed to Pantoea agglomerans) and lower activity levels were found in strains of genera Salmonella, Aerobacter, Pseudomonas, and Xanthomonas. Of all the strains with activity, E. herbicola ATCC21434 showed the highest activity and accumulated 0.26 mg/mL of L-Tyr or 0.125 mg/mL of L-DOPA per h incubation and was selected as the source of the enzyme in the following investigations.

| Genera | Strain numbers tested |

Strain numbers synthesized L-DOPA |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 635 | 22 |

| Pseudomonas | 201 | 2 |

| Xanthomonas | 2 | 1 |

| Alcaligenes | 47 | 1 |

| Achromobacter | 69 | 1 |

| Escherichia | 28 | 7 |

| Aerobacter | 23 | 1 |

| Erwinia | 98 | 5 |

| Proteus | 12 | 2 |

| Salmonella | 2 | 1 |

| Bacillus | 36 | 1 |

| Actinomycetes | 117 | 0 |

| Yeasts | 140 | 0 |

| Fungi | 138 | 0 |

L-DOPA synthesizing activity from D,L-serine and pyrocatechol was measured with intact cells of each strain belonging to the above genera. Intact cells were obtained from 0.2% L-Tyr-containing agar slants of bouillon media for bacteria or those of yeast-extracts-peptone media for yeasts, fungi, and actinomycetes. The reaction mixture was incubated at 31 °C for 4 h at pH 8.0 in the presence of approximately 70–100 mg of intact cells. No activity was found in the following bacterial genera, Acetobacter (16 strains), Aeromonas (4), Mycoplana (2), Vibrio (2), Azotobacter (3), Agrobacterium (2), Flavobacterium (5), Serratia (3), Micrococcus (13), Staphyrococcus (3), Sarcina (2), Brevibacterium (22), Corynebacterium (28), Arthrobacterium (16), and Cellulomonas (4). Two genera of Actinomycetes, 10 genera of yeasts, and 9 genera of fungi were submitted to this test. This table is reproduced from Ref. 10 with some modifications.

The activities of L-DOPA synthesis of bacteria collected from various natural sources were also measured. Although activity was detected in a few strains belonging to the genera Escherichia and Proteus from sewers, soil, fruit, and vegetables, a large numbers of strains from crops that are known to be sources of bacteria belonging to the genera Erwinia exhibited distinct activity, as shown in Table 2. Wild strains with activity were isolated mainly from rice and corn plants, but not from the grains. The highest activity shown by a wild strain was 0.145 mg/mL of L-Tyr and 0.065 mg/mL of L-DOPA accumulation per h of incubation, which were lower than that of E. herbicola ATCC21434.10)

| Source | Number of samples |

Number of strains picked up |

Number of strains that synthesized L-DOPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sewer | 12 | 228 | 1 |

| Soil | 16 | 145 | 2 |

| Fruit | 24 | 410 | 5 |

| Vegetable | 18 | 230 | 2 |

| Cereals (grains) | 7 | 205 | 0 |

| (rice plants) | 13 | 150 | 118 |

| (corn plants) | 5 | 52 | 21 |

| Total | 95 | 1,420 | 149 |

L-DOPA synthesizing activity was measured as described in Table 1. This table is reproduced from Ref. 10 with some modifications.

From this large-scale investigation of the distribution of Tpl in microorganisms, it was clearly shown that Tpl exists in bacteria, except for actinomycetes, but not in eukaryotic microorganisms such as yeast and fungi. Tpl was initially found in human intestinal flora, and research began on the enzyme that produces phenol from L-Tyr in the gut. However, among bacterial strains, it was also clarified that Tpl activity is distributed in other bacterial groups that inhabit crops. In addition, it was shown that they had higher Tpl activity than gut flora. Although the details are unknown, the biological relationship between this bacterium and rice or maize via L-Tyr and Tpl is interesting. This enzyme may have been specifically acquired by a bacterium during its evolution. Perhaps tpl was obtained by the bacteria to utilize L-Tyr present in its growing environment as a carbon source or nitrogen source. The fact that the enzyme activity is induced by L-Tyr may support this hypothesis.

Tpl was also reported to be produced by an obligately symbiotic bacterium strain, S. thermophilum, which grows in a co-culture with thermophilic Geobacillus strain.31)

In addition, it was reported that Tpl occurs in some arthropods, polydesmida millipedes, and that it derives from their body itself, not from symbiotic bacteria.32)

To obtain a pure enzyme preparation, it is essential to have bacterial cells that contain large amounts of the enzyme protein. Because Tpl is an inducible enzyme by its substrate L-Tyr, the effect of L-Tyr concentration in the culture medium on the formation of Tpl was investigated with E. intermedia. After cultivation in a bouillon medium containing peptone, yeast extract, NaCl and various concentrations of L-Tyr (0.05–1.0%), the maximal Tpl activity was observed at a concentration of 0.2% L-Tyr. Changes in Tpl activity during growth were also investigated with E. intermedia, and maximal formation of Tpl was observed at the end of the logarithmic phase of growth, and thereafter the enzyme activity decreased gradually with the consumption of L-Tyr added to the medium.30) The first homogeneous preparation of Tpl was obtained from the E. intermedia cells cultured in these conditions.5),6)

For the industrial production of L-DOPA with E. herbicola, because intact cells were going to be used directly as the biocatalyst, it was necessary to establish culture conditions in which the cells grew well and the enzyme would accumulate sufficiently in the cells. After cultivation in various culture conditions, cell growth was estimated and Tpl activity was measured with intact harvested cells in a reaction mixture containing DL-Ser and pyrocatechol.11) The concentration of L-Tyr to elicit high activity of Tpl was investigated, and the addition of 0.2% L-Tyr to the medium was confirmed again to be optimal.11),29) PLP was known to work as a coenzyme of Tpl, and its addition to the medium was examined in comparison with other vitamins. Because the addition of pyridoxine, a type of vitamin B6 and a precursor of PLP had shown the same effect as the addition of PLP. The basal medium for Tpl production contained 0.2% KH2PO4, 0.1% MgSO4•7H2O, 0.2% L-Tyr, and 0.01% pyridoxine HCl. Furthermore, various concentrations of extracted or hydrolyzed nutrients, carbohydrates, organic acids, amino acids, and metals were added to the basal medium to examine their effects on Tpl production. After cultivation in each medium, cell growth and enzyme activity were estimated. The activity was determined with intact harvested cells by monitoring the amount of L-DOPA synthesized from DL-Ser and pyrocatechol. Among extracted or hydrolyzed nutrients including yeast extract, polypeptone, meat extract, and soy bean-protein hydrolysate (Table 3, ①–④), soy bean-protein hydrolysate added at a concentration of 120 mL/L showed the highest growth and enzyme activity, as shown in Table 3, ④. Although this activity was slightly lower than that obtained with the addition of mixture of yeast extract, polypeptone, and meat extract (Table 3, ③), soy bean-protein hydrolysate was chosen because of its economic advantages. This table does not show the results of each experiment but shows the summary of following examinations of the effects of the additives to the medium. Further addition of various carbohydrates and organic acids to soy bean-protein hydrolysate-containing basal medium were tested, and it was found that glycerol was more suitable than glucose or organic acids, suggesting that glycerol promoted enzyme formation in the cells. Of 18 amino acids separately added to medium containing soy bean-protein hydrolysate, glycerol, and succinic acid, it was found that DL-alanine (Ala), L-phenylalanine (Phe), DL-methionine (Met), L-isoleucine (Ile), and glycine (Gly) increased the enzyme activity. Moreover, addition of the mixture of these amino acids increased activity much more (Table 3, ⑥). L-Ala and L-Phe are known as competitive inhibitors of Tpl, so they might inhibit Tpl activity to degrade L-Tyr, and L-Tyr added as the inducer may remain longer in the culture medium than in the absence of them, resulting in a remarkable enhancement of Tpl activity. Furthermore, L-Phe was found to especially enhance the production of Tpl in the growth of the cells, and this synergistic effect with L-Tyr may also be explained by the transcriptional control mechanism through the DNA-binding specific regulator protein TyrR, in which L-Phe also works as an effector to activate expression of the tpl gene. This mechanism will be introduced later in the section on transcriptional control of the tpl gene in this review. Additionally, out of 14 metal ions added to the medium, Fe2+ gave the highest growth and Tpl activity.

| Materials added and their concentration | Growth (OD) |

Rate of L-DOPA synthesis (mg/mL/h) |

|---|---|---|

| ① 0.5% Yeast extract | 0.085 | 0.16 |

| ② 2% Yeast extract | 0.24 | 0.34 |

| ③ 1% Yeast extract + 0.5% polypeptone + 0.5% meat extract | 0.23 | 0.37 |

| ④ 120 mL/L Hydrolyzed soy bean protein liquor | 0.34 | 0.36 |

| ⑤ ④ + 0.6% Glycerol, 0.5% succinate | 0.405 | 0.53 |

| ⑥ ⑤ + 0.2% DL-Ala, 0.05% Gly, 0.1% DL-Met, 0.1% Phe | 0.38 | 3.8 |

| ⑦ ⑥ + 10 ppm Fe2+ | 0.46 | 6.25 |

Basal medium for Tpl production contained 0.2% KH2PO4, 0.1% MgSO4•7H2O, 0.2% L-Tyr, and 0.01% pyridoxine HCl. Growth is shown as the OD at 562 nm. L-DOPA synthesizing activity was measured as described in Table 1. This table is reproduced from Ref. 11 with some modifications.

The effects of the other culture conditions involving aeration, pH and temperature were tested and the best conditions were obtained, respectively. As results, culture conditions for E. herbicola cells to give the highest Tpl activity was established as follows: cultivation at 27 °C for 28 h in a medium containing 0.2% L-Tyr, 0.2% K2HPO4, 0.1% MgSO4•7H2O, 0.01% pyridoxine•HCl, 0.6% glycerol, 0.5% succinic acid, 0.2% DL-Ala, 0.05% Gly, 0.1% DL-Met, 0.1% L-Phe, and 120 mL/L of hydrolyzed soybean protein liquor in tap water, with pH controlled at 7.5 during cultivation.11)

The enzymatic properties of Tpl proteins from E. intermedia (EiTpl),6),7) E. herbicola (EhTpl),33) and S. thermophilum (StTpl)34) which were purified to a homogeneous state are summarized in Table 4. The molecular masses of a single subunit of these enzymes were calculated from the amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences.18)–20),35) They were similar, and the quaternary structures of these enzymes were estimated to be a tetramer from the molecular size measured by gel filtration and/or electrophoresis. The coenzyme, PLP, was estimated to bind at a ratio of one per subunit,18),36) and the binding site amino acid residue was confirmed as a lysine (Lys) residue at position of 257 in the Tpl protein segment of C. freundii.37) The binding site of PLP was Lys257 in EiTpl and EhTpl and Lys259 in StTpl. Upon association with PLP, the enzyme showed absorption peaks at 340 and 420 nm. Absorption around 420 nm is common in many PLP-dependent enzymes and is characteristic of the internal aldimine. Three Tpls listed in Table 4 required K+ or NH4+ cations to show maximum activity, although Na+ also showed a lower activation effect.

| E. intermedia | E. herbicola | S. thermophilum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular mass of subunit | 51,441 | 51,364 | 52,269 |

| Subunit structure | Tetramer | Tetramer | Tetramer |

| Number of PLP coenzyme binding sites | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Cation requirement for maximum activity | K+, NH4+ | K+, NH4+ | K+, NH4+ |

| Substrates for α,β-elimination reaction | L or D-Tyr, L-DOPA, L or D-Ser, L-Cys, S-Me-L-Cys |

L or D-Tyr, L-DOPA, L or D-Ser, L-Cys, S-Me-L-Cys |

L or D-Tyr, L-Ser, L-Cys, S-Me-L-Cys, β-Cl-L-Ala |

| Km value for L-Tyr | 2.31 × 10−4 M | 2.78 × 10−4 M | 5.4 × 10−5 M |

| Otimum pH | 8.2 | 8.2 | 7 |

| Stable temperature | 0–40 °C | 0–40 °C | 0–80 °C |

This table is a summary of properties of Tpls described in Refs. 6 and 7 (EiTpl), Ref. 33 (EhTpl) and Ref. 34 (StTpl).

*The Km values were measured at 30 °C for EiTpl and EhTpl and 70 °C for StTpl.

EiTpl and EhTpl catalyzed the α,β-elimination reaction of L-Tyr, L-Ser, L-DOPA, L-cysteine (Cys), and S-methyl-L-cysteine (S-Me-L-Cys). A characteristic property of Tpl is the ambiguity of its activity on optical isomers in its substrate specificity. It can use D-form amino acids as well as L-form ones. This unique property was confirmed with three homogeneous enzyme preparations. StTpl showed a similar substrate specificity, but it showed especially high activities toward S-Me-L-Cys and β-chloro-alanine (β-Cl-Ala), and this seemed to be caused by the extremely high reaction temperature of the assay at 70 °C. The Km value of StTpl for L-Tyr was also very low compared with the other two enzymes, and this also seems to be caused by the high reaction temperature. The apparent kinetic parameter values are considered to be higher due to the higher measurement temperature, 70 °C. The optimum pH of EiTpl and EhTpl was the same at 8.2 but for StTpl it was pH 7. StTpl showed an extremely high stable-temperature region in the comparison of EiTpl and EhTpl. In the β-replacement reaction, amino acids that were used as the substrate in the α,β-elimination reaction were used for a L-Tyr derivative formation. Racemic or D-form amino acids were also used as the substrate, but the reaction products were limited to L-form only.10) The other substrate, phenol derivatives, were investigated in the β-replacement reaction and in the reverse reaction of α,β-elimination reaction, showing that various compounds were available, including pyrocatechol,8) resorcinol,38) pyrogallol,39) o- or m-methyl-, o- or m-chloro-, o- or m-fluoro-, o- or m-bromo-, m-iodo-, o- or m-methoxy-, and m-ethyl-phenol.13),40) In these synthetic reactions of Tyr derivatives, benzene derivatives with no hydroxyl-group and phenol derivatives having a substituted group at the para-position of the hydroxyl-group were not used as the substrate. It was also confirmed that all Tyr derivatives synthesized were L-form and that the Ala residue was attached at the para-position relative to the hydroxyl group.40) The specificity of the reaction with these phenolic compounds was considered to reflect the reaction mechanism of this enzyme. The study of the reaction mechanism of this enzyme will be described in the following section.

The multifunctional property of Tpl, which catalyzes α,β-elimination, β-replacement, and racemization reactions, can be explained by adopting the general mechanism for pyridoxal-dependent reactions, and the discovery of the reverse reaction14),15) contributed to the elucidation of the entire reaction mechanism of Tpl catalysis.13)

A schematic representation of the reaction mechanism is shown in Fig. 1A, where PLP initially forms an internal aldimine (Schiff’s base) with the ε-amino group of Lys257 residue in Tpl (Fig. 1A, (a) E+S). When the substrate L-Tyr binds to the catalytic pocket, a transaldimination reaction occurs between the substrate and the internal aldimine, to form an external aldimine with concomitant release of Lys257 (a→b). The amino group of Lys257 in turn deprotonates Cα of the substrate to form a quinonoid intermediate (b→c). β-Elimination proceeds via tautomerization of the aromatic ring assisted by a general base catalyst (arginine (Arg)381) and a general acid catalyst (Tyr71), which leads to the cleavage of the C-C bond with the liberation of phenol (c→d→e), as well as the formation of an α-aminoacrylate intermediate (E•AA). Thr124 is also crucial for β-elimination and probably serves as a residue fixing the hydroxyl group of phenol. Then, pyruvate is produced by the hydrolysis of α-aminoacrylate (e→f), and finally NH3 is released to form the internal aldimine (holoenzyme) (f→g). The amino acid residues that play important roles in the catalysis were deduced from the X-ray crystal structure analyses described next section.

(A) Schematic representation of the mechanism of tyrosine phenol-lyase catalysis. E; enzyme, S; substrate, ES; enzyme substrate complex, In.Al.; internal aldimine (shadowing part), Ex.Al.; external aldimine (shadowing part), ES1, ES2; enzyme substrate complex intermediates. E•AA; enzyme α-aminoacrylate complex, α-AA; α-aminoacrylate (shadowing part), Pyr; pyruvate. The active site is shown mainly by the cofactor, PLP, and the substrate is L-tyrosine. The amino acid residues of Tpl important in the catalysis are shown with numbered one-letter codes in accordance with CfTpl, and Tpl peptides connecting the residue are shown by wavy lines. This figure is reproduced from Refs. 13 and 43 with some modifications. (B) Catalytic processes of three reactions catalyzed by Tpl.

This is the catalytic course of the α,β-elimination reaction of L-Tyr, and the reverse reaction proceeds in the presence of high concentrations of the substrates phenol (or its derivative), pyruvate, and NH3. With high concentrations of these substrates, the reverse reactions to produce L-Tyr or L-DOPA proceed well, because these enzyme products have low solubility in water and appear and accumulate as crystals during the reaction. The last part of the α,β-elimination reaction of L-Tyr (Fig. 1A, d→e→f→g) was estimated from the analyses of the initial part of the reverse reaction (g→f→e→d). In the reverse reaction, typical Michaelis–Menten kinetics were observed with pyruvate and NH3, but phenol showed strong inhibition at a high concentration.13),40) The kinetic analysis not only revealed that the reaction proceeds through the ordered ter-uni mechanism of Cleland but also demonstrated that pyruvate is the second substrate to bind to the enzyme. It was also shown that the addition of NH3, but not pyruvate or phenol, to the enzyme induced a spectral shift near 420 nm, indicative of an external aldimine formation between PLP and NH3 (Fig. 1A, f). Addition of pyruvate following NH3 decreased the absorption, and upon addition of phenol, a new peak that corresponded to the quinonoid intermediate appeared at around 500 nm (Fig. 1A, d). Proton exchange should occur at the C-3 of pyruvate during incubation of the enzyme with NH3 and pyruvate, when α-aminoacrylate is formed from the two substrates at the active site. This was confirmed by following the proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra of pyruvate during incubation with EiTpl and NH3 in D2O. Peaks at δ2.5–2.6, attributable to the three hydrogens at the C-3 of pyruvate, disappeared as deuterium replaced these hydrogens (Fig. 1A, f$ \rightleftarrows $e). The optimum pH of this proton exchange of pyruvate was the same as that of the synthetic reaction of L-Tyr. This suggested that the rate of α-aminoacrylate formation governs the overall rate of the synthetic reverse reaction. To confirm this, EiTpl was pre-incubated with pyruvate and NH3 in the deuterium medium for various periods, then phenol was added to the reaction mixture to produce L-Tyr. In the analysis of 1H-NMR spectra of L-Tyr, no peaks attributable to the hydrogen at C-3 were observed in the spectrum of the synthesized L-Tyr after 4 h of pre-incubation (g→f$ \rightleftarrows $e→d→c→b→a). However, the spectrum obtained for L-Tyr that was synthesized without pre-incubation indicated that only the α-proton was replaced by deuterium. The ratio of the integral magnitude of the protons of C-3 to the aromatic protons was 2:4, which strongly supported the hypothesis that the formation of the α-aminoacrylate intermediate is the rate-limiting step for the L-Tyr synthetic reaction.13)

All taken together, NH3 should be the first to bind to the enzyme in the reverse reaction, while pyruvate and phenol should be the second and third, respectively. The Km values for pyruvate, NH3, and phenol were calculated to be 12, 20, and 1.1 mM, respectively, and the kcat value of the reverse reaction was 1.5-fold higher than that of the α,β-elimination reaction.13),40)

A β-replacement reaction occurs when an appropriate substituent enters the active site after the departure of phenol (Fig. 1A, e) and the reaction proceeds in reverse (e→d→c→b→a). The stereochemistry of the β-replacement reaction catalyzed by EiTpl was also studied by investigating the reaction of L-Tyr (stereo-specifically deuterated at C-β)41) with resorcinol. The configuration of deuterium in the product, 2,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine, was elucidated by β-Cl-Ala comparison with a stereo-specifically synthesized sample. The results showed that the exchange occurred with retention of configuration at C-β. In a study on the mechanism of the β-elimination of phenol from L-Tyr, an initial tautomerism that allows elimination of the phenolate anion, was postulated (Fig. 1A, c→d→e), and a mechanism involving an enzyme bound α-aminoacrylate moiety was discussed from the view point of stereochemical analysis.41) The stereochemistry and mechanism of the α,β-elimination and racemization reaction catalyzed by EiTpl was also investigated, showing that the α,β-elimination reactions of L-Ser, D- and L-Tyr proceeded with retention of configuration at C-β.42) In this study, it was observed that deuterium from the α-position of L-Tyr was partially transferred to C-4 of the phenol formed when the α,β-elimination reaction was carried out in H2O. On the C-C bond cleavage in the α,β-elimination reaction of L-Tyr, the authors proposed tautomerization of the p-hydroxyphenyl to a cyclohexadienonyl moiety prior to C-C cleavage (Fig. 1A, c→d). Protonation of the PLP-Tyr derived α-carbanion para to the phenolic OH group and removal of the OH proton transforms the p-hydroxyphenyl moiety, a poor leaving group, into a more reactive cyclohexadienoyl moiety. Elimination of phenol then occurs by a dienone-phenol rearrangement.42)

The racemization reaction of L- or D-Ala takes place according to the steps (a→b→c→b→a) in Fig. 1A, which involves the formation of a quinonoid intermediate (c) but does not involve α-aminoacrylate intermediate formation (e). Abstraction of the α-hydrogen atom of L-Ala was demonstrated by 1H-NMR spectral analysis, in which signals for the α-proton of the substrate disappeared when the reaction was performed in D2O, whereas the initial doublet derived from the β-proton of the substrate become a single peak. These results showed that the proton-deuterium exchange occurred at the α-position of L-Ala during the reaction.13)

Enzyme-bound α-aminoacrylate (E•AA) is the key intermediate in this proposed mechanism. Three reactions catalyzed by Tpl, the α,β-elimination reaction, β-replacement reaction, and racemization reaction, are explained to proceed via the steps shown Fig. 1A, B. The synthetic reaction of L-Tyr or L-DOPA proceeds via the reverse steps of the α,β-elimination reaction.43)

The crystal structure analysis of C. freundii (Cf) Tpl and analysis of the reaction mechanism based on the determined structure have been carried out in detail by many researchers, and several important research results have been reported, which will be outlined in this section.

The crystal structure of apo-CfTpl was determined by Antson et al.37),44) in 1993. Firstly they cloned CfTpl and deduced its primary structure from the DNA sequence. They also purified PLP binding peptide after fixation of the coenzyme by reduction of the holoenzyme with NaBH4 and confirmed the PLP binding amino acid residue as Lys257. They reported that in the tetrameric molecule of Tpl, two dimers (so-called catalytic dimers) are bound together through a hydrophobic cluster in the center of the molecule and interlocked with their N-terminal domain (NT) arms, and that each protein of the dimer has a similar domain architecture to that of aspartate aminotransferase.44),45) The PLP-binding Lys residue is positioned at the interface formed between the large and small domains of one subunit and the large domain of a neighboring subunit. The large PLP-binding domain as well as the active site location are structurally similar to those of aminotransferases. Most of the residues involved in the binding of PLP in aminotransferases occupied the sterically same positions in the structure of Tpl. This report presented the groundwork for structural investigations of Tpl, including studies on elucidation of the catalytic mechanism of Tpl.

The crystal structure of holo-CfTpl was determined at 1.9 Å resolution by Milić et al. in 2006.46) The structure not only revealed how the protein interacts with the PLP cofactor but also showed detailed coordination of the potassium ion that had long been known to be catalytically important. They also presented the structure of the apoenzyme at 1.85 Å resolution. Notably, both structures were solved using crystals obtained at pH 8.0, which is close to the optimal pH of the enzyme, whereas the previously reported structure of apo-TpL was determined with crystals obtained at pH 6.37) They observed two different active-site conformations, open and closed. The open conformation was characterized previously with crystals obtained at pH 6, and the closed one was observed with crystals obtained at pH 8.0, and this finding was a first in α,β-eliminating lyases. In the closed conformation, a considerable part of the small domain moves towards the large domain, which resulted in closure of the active site cleft with the catalytically essential Arg and Phe residues (see above) moving to the catalytic center. The closed conformation thus strongly suggested that closure of the catalytic pocket is essential for the reaction to occur and also provided the structural basis for the enzyme’s specificity towards its physiological substrate L-Tyr. Moreover, they may suggest that the closed conformation is suitable to support the model of the keto (imino) quinonoid intermediate (Fig. 1A, c)) in the reaction mechanism.

In 2008, Milić et al. reported the catalytic mechanism of Tpl based on analysis of the crystalline structure of the quinonoid intermediate.47) The work was motivated by the facts that, although the importance of quinonoid intermediates had long been claimed in catalysis by PLP-dependent enzymes, no accurate information was available from a structural viewpoint. They succeeded in trapping the L-Ala and L-Met intermediates of CfTpl in the crystalline forms and solved the respective structures at 1.9- and 1.95-Å resolutions. Their work unequivocally revealed the tripartite interaction between the enzyme, PLP, and the substrate that caused stabilization of the planar geometry of the quinonoid intermediate. Additionally, the crystal structure elucidated the reaction scheme for Ala racemization that comprises two bases, Lys257 and an activated water molecule. Lys257 and the water are connected by a hydrogen-bond network so that internal transfer of the Cα proton is possible. In that paper, the authors showed the important role of quinonoid intermediates in the reaction mechanism of Tpl based on the structure of the enzyme. Additionally, they succeeded in demonstrating the two-base mechanism of deprotonation by the Lys257 residue and a water molecule in the crystal structure, on the racemization, α,β-elimination, and β-replacement reactions, in which both the D- and L-form enantiomers are availed as the substrates.

Phillips et al. reported on the ground-state destabilization by Phe448 and Phe449 contributed to Tpl catalysis.48) They mentioned that experimental evidence on ground-state destabilization had been limited in contrast to the role of transition-state stabilization in enzyme catalysis. Previously, they found that crystals of Y71F and F448H mutant Tpls complexed with a substrate, 3-fluoro-Tyr, provided clear structural evidence for ground-state destabilization in catalysis.49) The two Phe residues, Phe448 and Phe449, are in close contact with the bound substrate side chain. They obtained mutant Tpls of these two residues and analyzed crystal structures of enzyme–substrate complexes to investigate the contribution of the two residues to the ground-state destabilization.50) They also reported on the effects of pressure and temperature on the formation of aminoacrylate intermediates of Tpl.51)

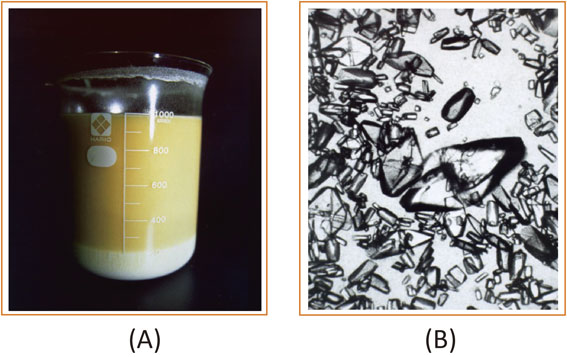

Reaction conditions were investigated to obtain high amounts of L-DOPA from pyruvate, ammonia, and pyrocatechol by a synthetic reaction of Tpl (Reaction c) in Scheme 1) using cells of E. herbicola with high Tpl activity.13),16) The optimum pH for this reaction was around 8.0, and the optimum temperature was 16 °C. Though the reaction rate was slow, low temperature was favorable because pyruvate shows high reactivity to cause unfavorable reaction as described below in the reaction mixture at higher temperature. The two substrates, pyruvate and pyrocatechol, were added at 2-h intervals to the reaction mixture to maintain the initial concentrations. Because pyrocatechol at high concentration strongly inactivated the enzyme by denaturation of the protein, and pyruvate at high concentration produced adducts with the product, L-DOPA, to reduce the amount of L-DOPA. Two by-products formed by the reaction between pyruvate and L-DOPA were isolated from a large-scale reaction mixture and were identified as isoquinoline derivatives, as shown in Fig. 2, which were expected to be formed through a spontaneous condensation reaction, Pictet and Springer reaction, between the synthesized L-DOPA and excess pyruvate (by-product 1), followed by a decarboxylation reaction (by-product 2) (Fig. 2).13),16) The effect of pyruvate concentration on L-DOPA synthesis was investigated with reaction mixtures containing various amounts of sodium pyruvate, 5 g of ammonium acetate, 0.6 g of pyrocatechol, 0.2 g of sodium sulfite, 0.1 g of ethylene-diamine tetra-acetate (EDTA), and cells of E. herbicola harvested from 100 mL of culture broth, in a total volume of 100 mL. The maximum synthesis of L-DOPA, 5.85 g/100 mL was obtained when the concentration of sodium pyruvate was kept at 0.5% (Fig. 3).13),16) L-DOPA is known to be rapidly oxidized by atmospheric oxygen in alkaline conditions, so the pH was kept at the optimum, 8.0, during the reaction by the addition of ammonia. Some heavy metals also accelerate this oxidation. To protect L-DOPA from such oxidation, sodium sulfite and EDTA were added as reducing and chelating agents, respectively. Because the solubility of L-DOPA in water is 0.5 g/100 mL at 20 °C, the L-DOPA synthesized precipitated as crystals in the reaction mixture (Fig. 4), which favored the reaction to proceed in the direction of L-DOPA formation.

Proposed reactions occurred in L-DOPA synthesizing reaction mixture. By-products 1 and 2 were isolated from the reaction mixture and identified using NMR and MS-spectra analyses as follows. By-product 1; 1-methyl-1,3-dicarboxy-6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline. By-product 2; 1-methyl-3-carboxy-6,7-dihydroxy-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline.

L-DOPA production with various concentrations of pyruvate. The reaction mixture contained various amount of sodium pyruvate, 5 g of ammonium acetate, 0.6 g of pyrocatechol, 0.2 g of sodium sulfite, 0.1 g of EDTA and cells of E. herbicola harvested from 100 mL of culture broth, in a total volume of 100 mL. The pH was adjusted to 8.0 during the reaction by the addition of ammonia. Sodium pyruvate was added to maintain the initial concentration of 0.35 (△), 0.5 (○), and 0.8 g (□) per 100 mL. The amount of L-DOPA is shown by solid lines (—) with open symbols and the by-product by dotted lines (- - -) with closed symbols. This figure was reproduced from Ref. 13.

Photographs of a reaction vessel after reaction containing precipitated L-DOPA (A) and crystals of L-DOPA obtained (B). This figure is reproduced from Ref. 52 with some modifications.

In the actual industrial production of L-DOPA in Ajinomoto Co., Inc., E. herbicola was cultured in a medium described in the section on culture conditions in this review. L-Phe and L-Tyr were added to the culture and the amount of the inducer L-Tyr was kept low as much as possible to avoid the contamination of the final product L-DOPA with L-Tyr. This is because the separation of L-Tyr from L-DOPA requires an extremely complicated process even at low L-Tyr concentration because L-DOPA and L-Tyr share similar structures. With optimized aeration and stirring, and also under the control of temperature and pH, cells containing Tpl at 15% of total protein were obtained. Then, the cells were collected by centrifugation, through which impurities such as phenol produced during the culture process by the decomposition of L-Tyr were removed, and then cells containing a high concentration of Tpl were supplied to the L-DOPA synthesizing reaction.

L-DOPA production activity was maintained during the reaction in the presence of coenzyme PLP and ammonia, which is not only one of the substrates but an activator of the enzyme. Additionally, the formation of by-products and the browning reaction of L-DOPA were prevented by the addition of a small amount of sodium sulfite and the metal chelating agent EDTA. The enzyme reaction proceeded smoothly using the precise feeding of pyrocatechol and pyruvate tuned to the rate of L-DOPA production. Because the reaction product, L-DOPA, has low solubility in water as described, it precipitated and accumulated as crystals during the reaction. This and the feeding of the substrate caused the reaction to proceed to the synthetic side. In optimum reaction conditions of pH 8.0 and 15 °C, the molar yield was as high as 98% with respect to pyrocatechol and 90% with respect to pyruvate after an approximately 12 h reaction, and as a result, 110 g/L of L-DOPA was accumulated in the reaction mixture. In addition, because most of the produced L-DOPA accumulated as large anhydrous plate-shaped crystals of high-purity, it was easy to separate from the enzyme-containing cells, and it was not necessary to dissolve and recover it using an organic solvent. L-DOPA was purified from the crude crystals at a high yield with a simple one-pass flow of UF filtration, de-colorization filtration, and recrystallization in a hydrochloric acid aqueous solution with a small amount of sodium sulfite and EDTA at low room temperature. Pure medical grade L-DOPA can be isolated and supplied as medical materials after drying and crushing. Currently, using WT E. herbicola cells containing high Tpl activity, L-DOPA was produced in 60 k-liter scale and Ajinomoto Co., Inc. supplies 110 tons of the agent to the commercial market every year.52),53)

Before the development of this Tpl enzymatic synthesis method, L-DOPA was mainly produced by chemical methods. Table 5 shows the differences between the chemical and the enzymatic methods. Whereas the enzymatic method required two steps, the cultivation of bacterial cells and the enzyme reaction, the chemical method required eight steps. The enzymatic method did not produce side products other than water, does not require an optical resolution, and does not require a long work schedule, with 3 days sufficient for the final preparation.52),53)

| Chemical method | Enzymatic method | |

|---|---|---|

| Main raw materials | Vanillin, hydantoin, hydrogen gas, acetic anhydride |

Pyruvate, ammonia, pyrocatechol |

| Reaction units | 8 | 2 |

| Side products | Ammonia, acetic acid, CO2 |

H2O |

| Optical resolution | Required | Not required |

| Working days | 15 days | 3 days |

| Impurities | Tyrosine, 3-methoxytyrosine, 3,4,6-trihydroxy- phenylalanine |

L-tyrosine |

This table is reproduced from Ref. 52 with some modifications.

The industrial production of L-DOPA by EhTpl had started and it was known that the tpl expression is induced by L-Tyr30) and repressed by glucose,11) and we had isolated the tpl gene of E. herbicola19) (accession No. D13714 in DDBJ, GenBank and EMBL). In these circumstances, however, the expression mechanism of tpl had not been studied. Elucidation of this regulatory mechanism of tpl was interesting and also useful for the industrial production of L-DOPA by this organism.

a) Analyses of transcriptional regulation of the tpl gene of E. herbicola.To elucidate the regulatory mechanism, northern blotting analysis was performed to detect the relative amounts of tpl mRNA during the cultivation of L-Tyr-induced and non-induced E. herbicola cells.21) The cells showed similar growth in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium with and without L-Tyr (Fig. 5). In cells grown with L-Tyr, the synthesis of tpl mRNA began in the middle of the exponential phase and reached a maximum in the late exponential phase. The findings suggested that the cells started to grow with preferable nutrients in the medium and then began to induce Tpl production to assimilate L-Tyr with the consumption of preferred nutrients. Although tpl expression was observed in the culture without addition of L-Tyr, which seems to be caused by a small amount of L-Tyr contained in LB medium, the amounts of mRNA expressed were less than one-tenth of that with L-Tyr (Fig. 5). This result showed that induction of Tpl by L-Tyr took place at the transcriptional level. Then, the effect of glucose on the tpl transcription was also examined using northern blotting analysis. It was shown that cells of E. herbicola grown in LB medium with L-Tyr had high amounts of tpl mRNA in the exponential growth phase, but after 1 h of incubation in the presence of glucose the amounts of the transcripts decreased by one-tenth. The effect of glucose was partially rescued by the addition of cAMP to the medium. The results indicated that tpl transcription was subjected to catabolite repression by cAMP receptor protein (CRP).21)

Inductive synthesis of tpl mRNA during the growth of E. herbicola. Total RNA was extracted from cells grown on LB medium with and without L-Tyr and 2.7 µg of total RNA was analyzed using northern blotting. The BglII–NaeI fragment of tpl from pSH76819) was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP and used as a specific primer. The membrane was exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography. The densities of hybridized bands were measured. Relative amounts of transcripts (with L-Tyr, □) and without L-Tyr,  ) were calculated by comparing with the maximum. Cell densities (with L-Tyr, -○- and without L-Tyr, -×-) were measured using OD600. This figure is reproduced from Ref. 21 with some modifications.

) were calculated by comparing with the maximum. Cell densities (with L-Tyr, -○- and without L-Tyr, -×-) were measured using OD600. This figure is reproduced from Ref. 21 with some modifications.

To have the information about the regulation mechanism of tpl expression, the 5′ flanking region of the tpl gene was analyzed and the transcriptional start point was determined by primer extension mapping at 121 bp upstream of the initiation codon of Tpl shown as +1 in Fig. 6. A presumed σ70 promoter sequence was identified by homology searches. Furthermore, three possible TyrR binding sites (consensus sequence TGTAAAN6TTTACA)23) existed, which were distributed fairly far from the transcriptional start point, as shown in Fig. 6. The binding site 1 (Box 1) was centered at −313.5, Box 2 at −200.5, and Box 3 at −85.5 with respect to the transcription start point. Two possible CRP binding sites (consensus sequence AAATGTATCT/AGATCACA TTT)54),55) were also present between TyrR binding site Box 1 and Box 2,22) even though they showed good agreement only in half (left or right)-arms and their faces of the double helix were not the same.

Structure of the upstream region of E. herbicola tpl. Transcriptional start point is shown as +1 and presumed −35 and −10 promoter regions are underlined. The bases with dots above are positioned with respect to the transcriptional start point (+1). Three TyrR binding sites are enclosed in shadowed boxes and designated as Box 1, 2, and 3. Two possible CRP binding sites are underlined with wavy lines. The Shine-Dalgarno sequence is shown with a double underline. The initial methionine residue followed by asparagine and seven amino acid residues are indicated under their respective codons. This figure is reproduced from Refs. 21 and 22 with some modifications.

To verify the involvement of the regulators TyrR and CPR in tpl regulation, we constructed a lactose operon (lac) fusion and investigated the mode of expression in E. coli cells, which had TyrR protein but no Tpl. The DNA fragment of the tpl upstream region shown in Fig. 6 was inserted into a plasmid carrying the ’lac gene, and the resultant tpl’-’lac fusion in the plasmid was integrated into the E. coli chromosome as a single-copy fusion to minimize experimental errors on assessing β-galactosidase activities.22) As shown in Table 6, in the tyrR+crp+ strain (TK314), the expression of tpl’-’lac fusion was induced by L-Tyr at a ratio of 32 in the presence of glycerol as a carbon source. The ratio of L-Tyr induction was 6.6 when cells were grown in the presence of glucose, indicating that catabolite repression actually occurred in this strain. These results indicated that the mode of expression of tpl in E. coli was similar to that in E. herbicola. In the tyrR mutant (TK157), the induction of tpl by L-Tyr almost completely disappeared whichever carbon source was used. The loss of induction ability was recovered when the cells were transformed with a plasmid containing E. coli tyrR+ (data not shown). The TyrR protein and its ligand L-Tyr should act as an activator of tpl in E. coli. In a tyrR+ strain (TK314), the change in the carbon source from glycerol to glucose in the presence of L-Tyr severely reduced the β-galactosidase value (2,270 to 352). However, in the tyrR mutant, such a significant reduction disappeared (55.7 to 46.0). Catabolite repression mostly disappeared in the tyrR mutant. As for the crp mutant (TK339), the induction of tpl by L-Tyr certainly took place at a ratio of 3.7 (Table 6). These results showed that the expression of tpl in the tyrR mutant was scarcely affected by CRP but the expression of tpl in the crp mutant was still activated by TyrR, which suggested that TyrR might play a major role in the transcriptional activation of tpl, such as an interaction with an RNA polymerase, while CRP act as the second factor.22)

| E. coli strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller U.) of strain grown in: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | Glucose | Glycerol+Tyr | Glucose+Tyr | ||

| TK314 | tyrR+, crp+ | 70.1 | 53.0 | 2,270 (32) | 352 (6.6) |

| TK357 | ΔtyrR | 51.6 | 43.5 | 55.7 (1.1) | 46.0 (1.1) |

| TK339 | Δcrp | NA | 57.5 | NA | 210 (3.7) |

| TK358 | ΔtyrR, Δcrp | NA | 41.2 | NA | 43.1 (1.0) |

This table is reproduced from Ref. 22 with some modifications. Details on the origin of E. coli strains and their genotypes are described in the reference. Relevant genotypes are conferred on TK314. Cells were grown on minimal medium containing 0.2% glycerol or 0.2% glucose as a carbon source; Tyr, 2 mM L-Tyr as an inducer of tpl. The numbers in parentheses indicate the ratio of induction by L-Tyr with the respective carbon source, glycerol or glucose. NA, not applicable because the crp mutant does not grow on glycerol. β-Galactosidase activity was measured using the method of Miller.56) Assays were done in duplicate on two separate cultures, and the values showed less than 10% error.

Three possible TyrR boxes are present in the upstream region of tpl gene, as is shown in Fig. 6. To investigate the function of these boxes in vivo as a TyrR binding site, we constructed a series of tpl’-’lac fusions carrying mutation(s) in box(es), as is shown in Table 7. Then, these tpl upstream variants were similarly fused to the lac gene and integrated into the E. coli chromosome. Furthermore, tyrR of E. herbicola was cloned as the gene encoding a positive regulator for tpl27) as described below and it was sub-cloned into a low copy number plasmid and then introduced into E. coli (TK357) strains that had tyrR mutation and a series of tpl’-’lac fusions (the procedure for the isolation of E. herbicola tyrR is described in the following section). The effects of TyrR box mutations on the expression of tpl’-’lac fusion were examined with obtained strains (Table 7). Every TyrR box mutation severely reduced the ratio of induction of tpl, and no induction was observed when all boxes were destroyed. The results indicated that each box actually functioned as a TyrR binding site in vivo and was significant in the Tyr-mediated activation of tpl.

| E. coli strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller U.) of strain grown in: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | Glucose | Glycerol+L-Tyr | Glucose+L-Tyr | ||

| TK680 | Wild-type TyrR boxes | 98.9 | 68.2 | 1,813 (18) | 786 (12) |

| TK681 | Box 1 mutation | 66.0 | 56.7 | 149 (2.3) | 136 (2.4) |

| TK682 | Box 2 mutation | 92.2 | 56.7 | 204 (2.2) | 86.4 (1.5) |

| TK683 | Box 3 mutation | 93.6 | 57.5 | 323 (3.5) | 160 (2.3) |

| TK684 | Box 1, 2, 3 mutations | 70.2 | 55.4 | 71.7 (1.0) | 59.5 (1.1) |

This table is reproduced from Ref. 22 with some modifications. Details on the origin of E. coli strains and their genotypes are described in the reference. Relevant genotypes are conferred on TK680. Cells were grown on minimal medium containing; 0.2% glycerol or 0.2% glucose as a carbon source; L-Tyr, 2 mM L-Tyr as an inducer of tpl. The numbers in parentheses indicate the ratio of induction by L-Tyr with the respective carbon source, glycerol or glucose. β-Galactosidase activity was measured using the method of Miller.56) Assays were done in duplicate on two separate cultures, and the values showed less than 10% error.

As described in the previous section, the lac reporter system of E. coli was used to examine the regulatory mechanism of tpl. Although E. coli does not possess the tpl gene, both L-Tyr-mediated induction and glucose-mediated repression of this gene were observed to a similar extent as observed in E. herbicola. Accordingly, the TyrR protein and CRP of E. coli should work as regulators of tpl that are responsible for L-Tyr induction and carbon catabolite repression, respectively.22) Nonetheless, we attempted to isolate the tyrR gene of E. herbicola, to elucidate the regulatory mechanism of tpl in anticipation of finding a reasonable strategy for constructing a high tpl-expression strain.

A derivative of E. coli strain JM10757) that carries the Φ(tpl’-’lac) gene with tyrR and a recA background was constructed. Then, using this strain as a host, a plasmid-based genomic library of E. herbicola was constructed and spread on MacConkey-lactose plates supplemented with 0.1% L-Tyr as an inducer. The transformants were screened for red color formation. As a second screening to eliminate picking up other genes such as β-galactosidase related genes or an unknown gene, plasmids extracted from red colonies were subsequently introduced into another E. coli strain, in which the upstream regulatory region of the tpl promoter was removed. When a gene encoding an activator of tpl was introduced into the strain, the expression of the Φ(tpl’-’lac) fusion would remain basal (forming a white color) because the activator longer no acted on its target region. On the other hand, in the case that other genes such as a β-galactosidase gene was introduced, transformants would be colored red again. With this screening strategy, 20 clones were isolated as positive. All of the extracted plasmids gave the same length DNA fragment upon EcoRI digestion and conferred the TyrR+ phenotype58) on the host strain with a tyrR null mutation. A plasmid with the shortest insert was selected by phenotype checking,58) and finally it was found that the gene of interest was contained in a 3.5-kb Sal I fragment. The DNA sequence of the fragment was deposited in GenBank (accession number AF035010). As expected, the cloned gene was tyrR.27)

The primary structure of EhTyrR27) was aligned and compared with those of other bacteria namely E. coli,59) Salmonella typhimurium,60) C. freundii (C. braakii),61) and Shigella dysenteriae.62) Although the TyrR proteins of these four bacterial strains exhibited marked resemblance (more than 90% identity), EhTyrR had shown relatively low similarity (less than 72% identity) to the others. All five TyrR proteins had almost identical two ATP-binding motifs in their central domains (Cen) and identical helix-turn-helix motifs in their C-terminal domains (CT).27) In Fig. 7, an amino acid alignment of EhTyrR is shown in comparison with EcTyrR. Only the E. herbicola tyrR gene encoded seven extra amino acid residues within the Cen; however, deletion of this region had no effect on its regulatory properties in E. coli.

Amino acid sequence alignment of TyrR proteins from E. herbicola and E. coli. The deduced amino acid sequence of the EhTyrR was aligned with that of the EcTyrR (GenBank accession number M12114).59) The two ATP binding sites (A and B) are enclosed by boxes. The sequence of the HTH motif is underlined with a wavy line. Mutations described in the following section on L-Tyr mediated conformational changes of TyrR are indicated by arrows labeled with their amino acid positions.

Wilson et al.63) reported L-Tyr-mediated conformational change of EcTyrR from a dimer to a hexamer. By reflecting this property, the Tyr-mediated repression of some E. coli genes involved in aromatic amino acids metabolism, such as aroLM and tyrosine-repressible 3-deoxy-arabinoheptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (aroF)-tyrA, occurs through this mechanism, in which the hexameric form of TyrR inhibits access of RNA polymerase to the promoters. Combined with these results, we proposed a possible model for the TyrR-mediated activation of tpl as follows (Fig. 8). Each of the three TyrR boxes are separated by eleven helical turns with two CRP-binding sites being located between the upstream two TyrR boxes. In non-induced conditions, i.e. when L-Tyr concentration is low, TyrR dimers are bound to the three distinct TyrR boxes. However, in induced conditions, i.e. in the presence of high concentration of L-Tyr, TyrR converts its conformation to a hexamer, and the distal TyrR bound to Box 1 would be pulled to the downstream promoter region so that it associates with RNA polymerase to trigger transcription. DNA bending triggered by the binding of CRP to the region located between TyrR Box 1 and Box 264),65) may facilitate hexamer formation of three TyrR dimers.22),26),52)

Proposed mechanism of induction of Tpl biosynthesis mediated by L-tyrosine and TyrR. (A) Non-inducing conditions: When L-Tyr concentration is low, TyrR dimers are separately bound to the three TyrR boxes upstream of tpl. (B) Inducing conditions: In the presence of L-Tyr, TyrR convert its conformation to a hexamer, and the distal Box 1-TyrR complex will move up to the downstream promoter region so that it can contact RNA polymerase to initiate transcription. DNA bending of the intervening region triggered by the binding of CRP facilitates the self-association of three TyrR dimers.

This ligand-mediated conformational change of EhTyrR was confirmed by gel filtration analysis followed by SDS-PAGE, as shown in Fig. 9.52) In this experiment, first, E. coli B strain was transformed with a plasmid in which the tyrR gene of E. herbicola was introduced. Gel filtration was performed with cell-free extracts of this transformant, and the obtained fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and EhTyrR-bands were detected using western blotting with anti-EhTyrR antibodies. Figure 9 is the result of this western blot analyses showing the bands detected at the position corresponding to the mass of the EhTyrR monomer (59,022 Da). As shown in Fig. 9A, when L-Tyr was not added to the extracts, the bands were observed at a slightly smaller size position than the gel-filtration fractions containing a standard protein with a mass of 160,000, indicating that EhTyrR existed as the dimer (molecular mass, 118,044). However, when L-Tyr and ATP were added to this and then gel filtration was performed, bands were observed at a smaller size position than the standard protein with a mass of 440,000 as shown in Fig. 9B, indicating that EhTyrR existed as a hexamer (molecular mass, 354,132). The addition of ATP alone did not show any change in molecular size (data is not shown).

Tyrosine mediated conformational change of E. herbicola TyrR. Cell-free extracts containing EhTyrR were fractionated by gel-filtration with Superdex 200 in the absence (A) and presence (B) of L-Tyr, and the obtained fractions numbered from 20 to 29 were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Ferritin (440 K) and aldolase (160 K) were used as molecular weight markers. Western blotting bands from SDS-PAGE corresponding to the molecular size of the TyrR monomer are shown. [Supplementary description; In this experiment, His-tagged EhTyrR was overexpressed in E. coli, but it was produced as an insoluble form. So the insoluble TyrR was isolated by SDS-PAGE and following DISC electrophoresis, then the purified His-tagged TyrR was used as the antigen to obtain an anti-TyrR antibody.] This figure is reproduced from Ref. 52 with some modifications.

Industrially, L-DOPA is produced by E. herbicola cells with high Tpl activity, which is cultivated in the presence of L-Tyr as the inducer. After harvesting the cells, they were transferred to a reactor containing the substrates pyruvate, pyrocatechol, and ammonia to start L-DOPA production. The microbial production of L-DOPA is thus simple and effective, but one unsolved severe drawback exists because of the addition of the inducer L-Tyr. The solubility of L-Tyr is very low in water; therefore, the remaining L-Tyr in the culture fluid is transferred together with the cells to the reactor and could not be removed even after finishing the reaction. Produced L-DOPA is used pharmaceutically; therefore, a very strict level of purity is required. The remaining L-Tyr in the reaction solution is extremely small, but its separation from L-DOPA is quite a complicated because of the structural similarity of these two compounds.

To avoid this drawback, the tpl genes of E. herbicola66),67) and C. freundii17) were cloned and heterologously expressed in E. coli under the control of the tac promotor. In either case, Tpl was highly induced in the presence of IPTG, but L-DOPA productivity was inferior to that of E. herbicola. The productivity of L-DOPA was thus influenced by unknown factors other than the tpl expression level, for example, the intake of substrates and the export of L-DOPA through the cell membrane. It is notable that E. herbicola carries only one copy of the tpl gene on its chromosome; nevertheless, it is the best choice for the L-DOPA production.

Given this situation and the mechanism of TyrR-mediated expression of tpl, we considered constitutive expression of Tpl in the presence of a specific mutant TyrR protein with an enhanced ability to form a hexamer without binding L-Tyr may lead to L-Tyr-free production of L-DOPA.

a) Random mutagenesis of the E. herbicola tyrR gene for high expression of the tpl gene.To obtain a mutant EhTyrR that constitutively activated tpl expression, random mutagenesis was carried out on the gene. The DNA region encompassing the open reading frame and putative transcription terminator of the E. herbicola tyrR gene was used as a template for error-prone polymerase chain reaction (PCR).68) The amplified DNA fragments were placed under the control of the WT tyrR promoter.69) Subsequently, an E. coli strain carrying the Φ(tpl’-’lac) and Δtyr::cat+ genes was transformed with two independently constructed mutant E. herbicola tyrR plasmid libraries. Transformants were spread on basal medium plates containing 2 mM 5-bromo-4-chlolo-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) to obtain about 50,000 transformants. The mutagenized E. herbicola tyrR genes were then screened for the ability of their products to induce tpl expression without supplementation with L-Tyr in the medium. The transformants were visually screened for enhanced blue color formation, and one-hundred colonies that showed deep blue were selected. Following confirmation of the phenotype on the same medium, five colonies exhibiting the deepest blue color were obtained as candidates. The β-galactosidase activities of these strains grown in basal medium are shown in Table 8.27) The highest activity was seen in the strain carrying the E. herbicola tyrR5 allele, which had three amino acid residue substitutions V67A, Y72C, and E201G, giving eight times higher activity than that of a strain carrying the WT E. herbicola tyrR gene. We analyzed the DNA sequences of the above five E. herbicola tyrR alleles (refer to Fig. 7) and found that the allele, named tyrR6, was identical to tyrR5. Even though these alleles were isolated from two independent screenings, the substitution of Ala for valine at position 67 (V67A) was seen in many alleles (tyrR2, tyrR3, and tyrR5), suggesting a significant effect of this mutation on the ability of EhTyrR protein to activate the tpl gene. We discussed the significance of other mutations in comparison with the case of EcTyrR in Ref. 27.

| tyrR allele | β-Galactosidase activity | Amino acid substitution(s) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 27.4 | |

| tyrR+ | 100 | |

| tyrR2a | 389 | V67A, V499I |

| tyrR3a | 393 | V67A |

| tyrR4a | 231 | D97G, I402V |

| tyrR5b | 863 | V67A, Y72C, E201G |

| tyrR6b | 850 | V67A, Y72C, E201G |

Four tyrR alleles (tyrR5 and tyrR6 were identical) were obtained through two different cycles of error-prone PCR (a; 25 PCR cycles, b; 30 PCR cycles). The randomly mutagenized tyrR gene was expressed under the control of the wild-type promoter in a pACYC-derived plasmid.27) The culture medium consisted of 0.5% peptone, 0.5% meat extract, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.2% KH2PO4. β-Galactosidase activity was measured using the method of Miller.56) This table is reproduced from Ref. 27 with some modifications.

To assess tpl expression levels in E. herbicola cells under the control of the product of tyrR5, which have substitutions V67A, Y72C, and E201G, we introduced this allele into E. herbicola. A tyrR-deficient E. herbicola strain was constructed and transformed with a plasmid carrying the tyrR5 allele. The transformant was grown in basal medium with and without the addition of L-Tyr. Whole cell extracts were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and the expression level of tpl was evaluated using immunoblotting with anti-Tpl antibodies. The resulting tyrR5 allele-carrying strain produced Tpl without the addition of L-Tyr to the medium, at the level comparable to the WT strain grown in L-Tyr-induced conditions.27)

Next, we tried L-DOPA production on a mini-industrial scale with recombinant E. herbicola cells carrying the tyrR5 allele. The strain was cultivated in the practically available medium16) with and without the addition of 0.1% L-Tyr. The growth of recombinant cells was good regardless of the presence or absence of the inducer L-Tyr. The cells stably maintained the plasmid during cultivation up to 43 h. L-DOPA productivity of these cells was considerably improved. The ΔtyrR strain carrying the plasmid with the WT E. herbicola tyrR gene (tyrRWT/ΔtyrR) produced an increased amount of L-DOPA compared with the WT strain regardless of whether culturing with or without L-Tyr, maybe because of the gene dosage effect. In the case of the recombinant strain carrying tyrR5, the cells produced significant levels of L-DOPA even in the absence of L-Tyr, but still the addition of L-Tyr to the medium was needed to maximize productivity.70) (These results are shown in the section on Development of an L-DOPA hyper-producing E. herbicola strain with a figure on page 95.)

b) TyrR mutants with altered oligomerization properties.Kwok et al.71) reported that EcTyrR, in which position 274 was exchanged from glutamic acid to glutamine, showed defects in oligomer formation.72) Although binding to ATP was normal in this mutant EcTyrR, L-Tyr-mediated hexamer formation was severely impaired, suggesting that this amino acid residue plays an important role in the dimer-to-hexamer conversion process. Therefore, we attempted to isolate second-site suppressors of the corresponding EhTyrR mutant protein.

In accordance with this report, the corresponding mutant (EhTyrRE275Q) lost the ability to activate tpl (Table 9). This may be because of a defect in hexamer formation, and we aimed to isolate a second-site repressor by introducing random mutations; a mutant library of EhTyrRE275Q was constructed and its ability to activate the Φ(tpl’-’lac) gene (pTK871) was screened for.27),28) Error-prone PCR was again performed on plasmid libraries constructed as described above in the E. coli ΔtyrR strain. Transformants were visually screened for enhanced blue color formation on LB plates containing 1 mM X-Gal,57) and four transformants were selected for sequence analysis of the mutant E. herbicola tyrR gene. Analysis revealed that all alleles had the E275Q substitution, but their products restored the ability to activate tpl to the same extent as WT tyrR in E. herbicola (Table 9).

| tyrR allelea | β-Galactosidase activityb | Amino acid substitution(s)c |

|---|---|---|

| None | 24 | |

| tyrR+ | 160 | |

| tyrRE275Q | 55 | |

| tyrR7 | 160 | N324D |

| tyrR8 | 120 | R215Q, N324D |

| tyrR9 | 210 | A503T |

| tyrR10 | 160 | S25G, N324D |

a; The respective tyrRE. herbicola genes were placed under the control of the wild-type promoter of tyrR in the pACYC-derived plasmid pTK774,28) and the resulting plasmids were introduced into the Φ(tpl’-’lac)-carrying strain (pTK871/TK596).

b; The strains were grown in LB medium at 37 °C, and the assays were done using the method described by Miller.56)

c; All mutant tyrR alleles possessed the E275Q substitution in addition to the newly introduced mutation(s) indicated.

[Supplemental description; To obtain these mutant, error-prone PCR and subsequent construction of the plasmid library was performed as described in the text, except that a plasmid carrying tyrRE275QE. herbicola, pTK815 (p15A replicon bla+ tyrRE275QE. herbicola) was used as the template for PCR. The plasmid library was used to transform E. coli ΔtyrR strain TK596 [F− ara Δ(lac-pro) thi ΔtyrR::kan+ Δ(srl-recA)306::Tn10]28) carrying pTK871.] This table is reproduced from Ref. 28 with some modifications.

The most elevated expression was observed in the strain with E. herbicola tyrR9, which has an A503T substitution in the CT DNA-binding domain. Thus, it is unlikely that this substitution is closely involved with the hexamer formation of TyrR.28) Although the reason why this amino acid substitution rescued the ability of EhTyrRE275Q to activate tpl is unclear, this mutation is very useful for enhancing tpl gene expression. Breeding of tpl high-expressing strains incorporating this mutation in combination with other mutations is discussed in the next section. The other three E. herbicola tyrR alleles shared a mutation (N324D) that replaces asparagine-324 with aspartic acid (Table 9); N324 is located in the Cen and was conserved in all mutant EhTyrR proteins identified, suggesting the involvement of this residue in the oligomerization process. Therefore, we focused on this residue and performed the following experiments.

First, we generated various N324 mutants of EhTyrR and examined their regulation in vivo. A severe growth defect, however, was seen in the E. coli strain expressing EhTyrRN324D when cultivated in the minimal medium without aromatic amino acids or shikimic acid, suggesting that the mutant EhTyrR protein severely repressed gene expression responsible for aromatic amino acid biosynthesis.73) Therefore, we decided to use EcTyrR instead of EhTyrR for further analysis, because the corresponding EcTyrR mutant (TyrRN316D) did not cause such severe growth retardation. Site-directed mutagenesis of the E. coli tyrR gene was performed using the QuikChange method (Stratagene) using pTK723 (p15A replicon bla+ tyrRE. coli)28) as a template and oligonucleotides carrying the desired mutation.

The tpl and the lac genes were translationally fused and used as a reporter.27) A plasmid carrying this reporter gene, Φ(tpl’-’lac) (pTK871), was introduced into an E. coli strain carrying the mutant E. coli tyrR gene on another compatible plasmid (Fig. 10 legend). These strains were cultured in M63 glucose minimal medium56) with or without the addition of 1 mM L-Phe or L-Tyr. The production level of respective EcTyrRN316 mutant proteins was confirmed to be essentially the same through immunoblotting with anti-EhTyrR antibodies (data not shown). The N316 substitutions affected the regulatory properties of EcTyrR in various ways, with the N316D/E and N316K/R substitution among the mutants that exhibited marked changes (Fig. 10). Activation of tpl in the presence of L-Tyr was enhanced in cells with EcTyrRN316D compared with cells with WT EcTyrR. Elevation of tpl activation by 2.5-fold was also observed in the presence of L-Phe with EcTyrRN316D compared with the WT EcTyrR protein. Thus, tpl expression was markedly increased, suggesting an enhanced self-association ability in this mutant EcTyrR protein. It was notable that the N316D substitution overcame the effects of the E274Q substitution as described above, indicating N316D as a second-site suppressive mutation against E274Q. A similar mode of regulation was observed for tpl expression levels in strains with EcTyrRN316E replacing N316 with an acidic residue thus appears to promote the TyrR self-association.

Effect of N316 substitution in E. coli TyrR protein on ligand-mediated activation of the tpl gene. pYG541 (pSC101 replicon bla+) (none), pYG543 (pSC101 replicon bla+ tyrR+E. coli) (wild-type), or pYG543-derived plasmids with the mutant tyrRE. coli genes were introduced into strain TK59628) (see Table 9 legend) carrying Φ(tpl’-’lac). Cells were grown in M63-0.2% (wt/vol) glucose minimal medium56) supplemented with 1 µg/mL thiamine-HCl and 30 µg/mL proline in the absence (open bars) or presence of 1 mM L-Phe (filled bars) or L-Tyr (shaded bars), and β-galactosidase activities were measured. Assays were carried out in duplicate for at least two separate cultures, and the average values are shown. This figure is reproduced from Ref. 28 with some modifications.

On the other hand, cells with EcTyrRN316K/R showed significantly reduced ligand-mediated activation compared with cells with the WT EcTyrR (Fig. 10). This result suggested that the self-association ability of the mutant TyrR protein was weakened; replacing N316 with leucine, Ala, Cys, or histidine did not significantly affect the regulatory ability in the EcTyrR protein.

Next, the oligomer-forming ability of these mutant EcTyrR proteins in the presence of ligand components was analyzed using gel-filtration chromatography and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 11). Purification of each mutant EcTyrR protein was performed in accordance with the method of Argaet et al.73) Gel filtration analysis was performed in the presence or absence of 100 µM ATP and aromatic ligands L-Tyr or L-Phe. The EcTyrR protein never oligomerized without the addition of ATP, even in the presence of aromatic amino acids. For the WT EcTyrR protein, oligomerization occurred in the presence of both ATP and aromatic amino acids L-Phe or L-Tyr. For EcTyrRN316D, on the other hand, oligomerization was observed with the addition of ATP alone. The presence of aromatic amino acids also promoted hexamer formation by stable self-assembly of the EcTyrRN316D protein compared with the WT EcTyrR (Fig. 11). These results were consistent with the changes in regulatory function of EcTyrRN316D observed in vivo; the enhanced hexamer-formation ability of the mutant protein led to strong tpl activation. The conformational change of this mutant protein in the presence of aromatic amino acids was reversible (data not shown).

Ligand-mediated conformational change of E. coli TyrR with N316 mutations. Size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 HR10/30 column) of the wild-type EcTyrR, EcTyrRN316D, and EcTyrRN316R proteins was carried out with or without 100 µM ATP and the indicated concentrations of L-Tyr or L-Phe, and the fractions containing TyrR proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 staining. Ferritin (440 K) and aldolase (160 K) were used as molecular weight markers and their elution position are shown with arrows. A pre-stained protein marker Broad Range (New England BioLabs) was electrophoresed next to the samples as shown on the left and center of the gel (MW; bands for 62 K and 47.5 K are visible). The molecular size of the TyrR monomer was 59,022 Da. This figure is reproduced from Ref. 28 with some modifications.

EcTyrRN316R, in contrast, formed only a dimer in all conditions tested by gel filtration, although a slight elution size shift was observed when the L-Tyr concentration was increased up to 750 µM (Fig. 11). This result also explained the reduced activation of tpl seen in this mutant in vivo.28)