Article ID: pjab.101.006

Article ID: pjab.101.006

Thrombomodulin (TM) is an important regulator of intravascular blood coagulation and inflammation. TM inhibits the procoagulant and proinflammatory activities of thrombin and promotes the thrombin-induced activation of protein C (PC) bound to the endothelial PC receptor (EPCR). Activated PC (APC) inactivates coagulation factors Va and VIIIa, thereby inhibiting blood clotting. Additionally, APC bound to EPCR exerts anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects on vascular endothelial cells. TM also protects cells in blood vessels from inflammation caused by pathogen-associated and damaged cell-associated molecules. Excessive anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, and tissue regenerative effects in the TM-PC pathway are controlled by PC inhibitor. A recombinant TM drug (TMα), a soluble form of natural TM developed from the cloned human TM gene, has been evaluated for efficacy in many clinical trials and approved as a treatment for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) caused by diseases such as sepsis, solid tumors, hematopoietic tumors, and trauma. It is currently widely used to treat DIC in Japan.

In the mid-1950s, antithrombin III (now called antithrombin [AT]) was identified through analysis of the mechanism of action of heparin, which inhibits blood coagulation reactions. AT was recognized as a major coagulation inhibitor in the blood. AT was a known protease inhibitor that inhibited protease clotting factors such as thrombin and factors Xa and IXa. However, the existence of inhibitors for factors VIII and V, which are non-protease clotting factors (referred to as cofactors) that maximally amplify the clotting reaction, was unclear.

In 1976, Johan Stenflo of Lund University, Sweden, who had discovered the Ca2+-binding amino acid γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) in vitamin K-dependent proteins, found a new Gla-containing protein of unknown function in bovine plasma, which was named protein C (PC) (62kDa).1) From structural analysis he deduced that PC was a type of protease precursor and tried to elucidate its function. Concurrently, a group led by Walter Seegers of Wayne State University in the United States found a substance produced in a prothrombin fraction treated with thrombin that inactivated the coagulation-promoting factors V and VIII; they proposed naming it factor XIV. Dr. Stenflo believed that factor XIV was PC and hypothesized that PC, once activated by thrombin (activated PC [APC]), degrades factors V and VIII, thereby inhibiting the coagulation reaction. In these circumstances, the author had the opportunity to study in Dr. Stenflo’s laboratory and studied the proteolysis of activated factor V (factor Va, composed of H and L chains) using purified human APC. We analyzed the relationship between changes in factor Va components and factor Va activity and revealed that the degradation of the factor Va-H chain by APC was the cause of inactivation.2) Despite elucidation of the mechanism of action of APC, at that time, PC was not considered a physiologically important coagulation inhibitor because its activation rate by thrombin was extremely slow in in vitro experiments.

In 1981, Esmon and Owen from the University of Oklahoma conducted pharmacological experiments using a rabbit blood circulation model and discovered that vascular endothelial cells contained a substance that significantly promoted PC activation by thrombin.3) Subsequently, the Esmon group isolated a thrombin-binding protein from solubilized rabbit lung tissue using inactivated thrombin cross-linked agarose column chromatography. They recognized that this substance inhibited fibrin coagulation caused by thrombin and increased PC activation by thrombin more than 1,000 times. They named it thrombomodulin (TM) because it was a modifier that converted thrombin’s function from promoting coagulation to inhibiting coagulation.4) The molecular weight of purified rabbit TM was determined to be approximately 74kDa based on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis. The affinity of TM for thrombin was calculated to be Kd \(\approx\) 0.05 nM [1], indicating that TM binds very strongly to thrombin. Subsequently, human TM was purified from placenta by Salem et al.,5) and it was verified that, like rabbit TM, it significantly promoted PC activation by thrombin.

The discovery of TM highlighted the importance of the TM-PC pathway (Fig. 1), which exerts anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective effects, functioning as a negative feedback mechanism of the coagulation/inflammatory system through the activation of PC by thrombin.

Overview of the blood coagulation pathway and the TM-PC anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory pathway. (Adapted from Fig.1 in Ref. 122.) Thrombin, which is generated in the blood coagulation reaction activated by the TF/factor VIIa complex, induces fibrin clotting and activates PAR1 on platelets, leukocytes, and vascular endothelial cells, leading to inflammation and thrombus formation. TF/factor VIIa is inhibited by tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and thrombin, factor Xa and factor IXa are inhibited by AT in the presence of heparin. Thrombin bound to the TM of vascular endothelial cells efficiently activates PC bound to EPCR to generate APC. APC binds to free PS and inactivates the coagulation cofactors Va and VIIIa, leading to inhibition of blood coagulation. The APC cofactor activity of PS is suppressed by a complement regulator, C4BPβ. Furthermore, thrombin bound to TM abolishes fibrin coagulation ability and PAR1 activation ability. APC that binds to EPCR on vascular endothelial cells activates PAR1 by cleaving at a site different from that of thrombin, inducing anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects. APC and thrombin-TM complexes are inhibited by PCI. In contrast, the thrombin-TM complex activates TAFI competitively with PC activation. TAFIa cleaves the C-terminal Lys residues of fibrin molecule, which are the binding sites for tPA and plasminogen, and inhibits plasminogen activation by tPA on fibrin and fibrin degradation by plasmin (fibrinolysis). Abbreviations: APC: activated protein C, AT: antithrombin, C4BPβ: C4b-binding protein with a β-chain, EPCR: endothelial protein C receptor, FDP: fibrin degradation products, PAR1: protease-activated receptor 1, PC: protein C, PCI: protein C inhibitor, PS: protein S, TAFI: thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, TAFIa: activated thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, TF: tissue factor, TFPI: tissue factor pathway inhibitor, TM: thrombomodulin, tPA: tissue-type plasminogen activator.

Human TM, also known as CD141 or BDCA-3, is present in a wide range of tissues and cells in the body. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that TM is associated with a variety of tissues and cells, including endothelial cells of arteries, veins, and capillaries that line blood and lymphatic vessels throughout the human body, and epithelial cells such as syncytiotrophoblasts in the placenta, peritoneum, intestine, mucosa, esophagus, alveoli, and respiratory system.6) TM is also present in blood cells such as platelets and leukocytes. In human platelets, it has been shown that there are approximately 60 functionally active TM molecules per platelet.7) In the brain, TM is reported to be present in blood vessels such as those of the neocortex, cerebellum old medulla, and hippocampus, but not in blood vessels in the putamen, pons, or midbrain.8) TM is transiently observed in undifferentiated tissues of the skin and fetal embryos, and its expression increases in tumor tissues such as mesothelioma and lung adenocarcinoma.9) Therefore, TM is thought to maintain the fluidity of blood and body fluids by preventing coagulation and inflammation, but it also plays a role in cell proliferation and differentiation in tissue proliferation and angiogenesis in tumorigenesis.

TM gene expression in vascular endothelial cells increases with stimulation, such as that by moderate shear stress, vitamin A, cAMP, histamine, adenosine, statins, prostaglandin E1, and interleukin (IL)-4. Conversely, it decreases due to stimulation by very weak or very strong shear stress, hypoxia, or high concentrations of thrombin, and inflammation-related factors such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1β, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), transforming growth factor-β, C-reactive protein, and oxidized low density lipoprotein. The promoter region of the TM gene contains a binding site for transcription factors that affect TM expression, such as specificity protein 1, activator protein 1, heat shock element, E26 transformation-specific sequence motifs, thyroid hormone/retinoic acid response element, and shear stress responsive element.10) Nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 2 and Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) together control approximately 70% of the shear stress-induced gene set. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 2 induces anti-inflammatory/antioxidant enzymes, and KLF2 induces anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant proteins, most specifically TM and endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase. KLF2 also inhibits proinflammatory and antifibrinolytic genes through inhibition of the proinflammatory transcription factors activator protein 1 and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB).11) Further, inhibition of the N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 (NDRG-1) significantly increased the expression of anti-thrombotic factors, such as TM and tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), and reduces the expression of procoagulant molecules such as plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) and tissue factor (TF).12) Therefore, anti-inflammatory factors such as vitamin A, cAMP, adenosine, and statins may suppress NDRG-1 expression in endothelial cells, and pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and LPS may stimulate NDRG-1 expression.

Homocysteine, an atherosclerosis-inducing substance, degenerates and inactivates TM on the surface of endothelial cells, induces abnormal TM mRNA expression, and promotes intravascular coagulation.13) These results suggest that increased expression of TM suppresses inflammation, and its decrease promotes inflammation and increases thrombosis.

Heterogeneous soluble TM fragments circulate in plasma and are considered a marker of vascular endothelial damage. Plasma TM concentrations increase in response to small vascular endothelial damage caused by conditions such as atherosclerosis,14) diabetes, collagen disease, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and inflammatory diseases of lung tissues, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome.15)

The expression of mouse TM has a circadian rhythm and, contrary to the fluctuations in PAI-1 gene expression, it increases during the dark period and decreases during the light period.16) This phenomenon may be related to the fact that thrombotic diseases occur more frequently in the morning in humans.

Following the isolating method used by Esmon et al. for TM from rabbit lungs, we purified human TM (78 kDa) from lungs and placenta in 1983 and determined its NH2-terminal amino acid sequence. Subsequently, through joint research with the Asahi Kasei Life Science Institute, we began cDNA cloning of human TM. An λgt11 cDNA library, prepared from umbilical vein endothelial cells, was screened using an anti-human TM rabbit antibody; 23 TM cDNA clones were obtained. At that time, PCR methods and automatic DNA sequencers had not been developed, and cDNA structural analysis was extremely difficult. However, after repeated primer extension analysis, one of the cDNA clones obtained was a true TM cDNA with the same NH2-terminal sequence as the TM protein. In the fall of 1986, the structure of the full-length human TM cDNA was elucidated. We expressed the TM cDNA plasmid in COS-1 cells, derived from SV40-transformed African green monkey kidney, and confirmed the presence of the recombinant protein on the cell surface, as detected using an anti-TM antibody. Then we published a paper in 198717) and obtained a world patent. We also revealed that the TM gene (THBD) lacks introns.18)

The human TM precursor has a signal peptide consisting of 18 amino acids, whereas the mature TM molecule is a type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein consisting of 557 amino acids and composed of five domains (Fig. 2). The extracellular NH2-terminal domain (D1) is composed of two functional modules, and the terminal module of 155 amino acid residues is homologous to the C-type (Ca2+-dependent) lectins of CD93 and CD248, which are involved in inflammation and innate immunity. After D1, domain (D2) containing six epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like modules, with the EGF3-EGF6 modules involved in anticoagulation and anti-fibrinolysis. D2 is followed by a serine-threonine-rich domain (D3) that serves as an O-linked glycosylation site to which chondroitin sulfate and other molecules bind. This is followed by a transmembrane domain (D4) consisting of 24 amino acid residues, and a cytoplasmic domain (D5) consisting of 36 amino acid residues. It is thought that molecules involved in changes in TM expression on the cell membrane bind to these regions.

Molecular model and functional domains of human thrombomodulin (TM). (Adapted from Fig.2 in Ref. 122.) D1: lectin-like domain, D2: domain consisting of six EGF modules, D3: Ser/Thr-rich domain, D4: transmembrane domain, D5: cytoplasmic domain. Abbreviations: EGF: epidermal growth factor, LPS: lipopolysaccharide, HMGB1: high mobility group box-1, TAFI: thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, GPR15: G-protein coupled receptor 15, PF4: platelet factor 4.

The cloning of human TM cDNA was conducted with the aim of elucidating the detailed structure of TM and developing a new therapeutic agent (an injectable drug) for disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) associated with serious thrombotic disease. Therefore, a recombinant soluble TM with sufficient anticoagulant activity was developed and, based on the above TM cDNA structure, it was composed of an extracellular domain excluding the cell membrane-spanning domain (D4) and the cytoplasmic domain (D5). The recombinant TM proteins (D123, D12, D1, D2, and D23) were expressed in COS-1 cells, and their activity was measured. When comparing the potency (units/mol × 107) for promoting PC activation by thrombin with purified human TM, the results were as follows: TM: 7.9, D123: 7.6. D12: 2.2, D1: 0, D2: 11.6, and D23: 35.0. This indicated that the D2-containing structure is necessary for PC activation by thrombin.19) Furthermore, among the six EGF modules that make up D2, we found that EGF456 is the minimum structure necessary for PC activation.20)

Considering the PC activation ability, recombinant protein expression efficiency, stability, etc., clinical trials were conducted with D123 protein (recombinant human soluble TM [rhsTM])19) as a therapeutic drug candidate.

The physiological activity of TM was analyzed using TM protein purified from cow or rabbit lungs, or human placenta extracts, through diisopropylphosphate-inactivated thrombin column chromatography, as well as various rhsTM proteins mentioned above. Currently, TM is known to have: (1) actions to inhibit the procoagulant activity of thrombin (anticoagulant action, anti-inflammatory action), (2) actions to promote PC activation by thrombin (anticoagulant action, anti-inflammatory action, cytoprotective action), (3) actions to promote activation of thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) by thrombin (antifibrinolytic action, anti-inflammatory action), and (4) various effects of TM itself (anti-inflammatory action, cytoprotective action) (Fig. 2). Below, the anticoagulant, antifibrinolytic, anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective, and tissue repair effects of TM are discussed in relation to the structure of the TM involved. Furthermore, this review describes the inhibitory mechanism of the TM-PC anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory pathway by protein C inhibitor (PCI), serine protease inhibitor (SERPIN) A5, and the unique functions of PCI beyond thrombosis and hemostasis.

6.1. Inhibition of the procoagulant activity of thrombin by TM.Through limited proteolysis, thrombin converts fibrinogen to fibrin, causing fibrin clotting, and further activates coagulation factors V, VIII, XI, and XIII. Thrombin also activates through limited proteolysis of the NH2-terminal Arg41-Ser42 site of protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) (113 kDa) on platelets, causing platelet aggregation. Furthermore, thrombin activates PAR1 on vascular endothelial cells and leukocytes, promoting the production of TF and various inflammatory cytokines in cells and causing blood coagulation and inflammation.

The binding site of TM in thrombin was suggested to be a region called exosite 1 and its surrounding area, which contains residues Thr147 to Ser158 of the B-chain of thrombin.21) A dodecapeptide synthesized from this region not only blocked the interaction between thrombin and TM but also the interaction between thrombin and its procoagulant substrates fibrinogen, factor V, hirudin, and PAR1 of platelets, endothelial cells, and leukocytes.22) Functional mapping analysis, in which amino acid residues on the surface of human thrombin molecules were replaced with alanine and changes in reactivity with thrombin substrates were measured, suggests which amino acids interact with each thrombin substrate.23) Using data from the functional mapping analysis, we constructed a CG model of the amino acid residues on the thrombin molecule that interact with fibrinogen (Fig. 3A) and amino acid residues that interact with TM and/or PC (Fig. 3B).24) The results indicated that TM inhibited the limited proteolysis of fibrinogen by thrombin by competitively binding to exosite 1, one of the binding sites for fibrinogen on thrombin. It has also been suggested that TM binding to thrombin exosite 1 changes the conformation of thrombin and promotes limited proteolysis of the PC-activation peptide.

CG molecule of thrombin and amino acid residues on the surface of thrombin, interacting with (A) fibrinogen and with (B) TM and/or PC (Ref. 24). (A) Amino acid residues on the thrombin molecule that influence clotting of fibrinogen by thrombin are shown. Fibrinogen interacts with exosite 1 and several amino acid residues (blue) surrounding the active center (Arg-His-Ser residues forming the active center in red) of thrombin (Connolly model, PDB ID: 1ABJ). (B) Amino acid residues on the thrombin molecule that influence PC activation by thrombin in the presence of TM are shown in yellow. The picture shows a complex of a peptide of the fifth EGF domain of TM (pink stick model) bound to exosite 1 in thrombin. TM interacts with thrombin exosite 1 and PC interacts with amino acid residues (yellow) surrounding the active center of thrombin. The D167 and D172 residues of the PC activation peptide repel the E25 and E202 residues (magenta), respectively, around the thrombin active center in the absence of TM, but when thrombin binds to the TM, the repulsion disappears (Connolly model, PDB ID: 1HLT). Abbreviations: EGF: epidermal growth factor, PC: protein C, TM: thrombomodulin.

X-ray crystal structure analysis of thrombin, and the recombinant TM-EGF 4-6 protein complex, revealed that the TM binding site on the thrombin molecule is located at thrombin exosite 1.25) In fact, genetic analysis of patients with TM gene homozygous disorder (patients with the TM-Nagasaki molecule) who exhibited DIC symptoms caused by hypercoagulation, fibrinolysis, and inflammation due to the inability to activate PC and TAFI, revealed an amino acid mutation (Gly412Asp) in the EGF5 region of TM.26) As shown in Fig. 4, it was assumed that the Gly412Asp mutation in the EGF5 region of the TM-Nagasaki molecule disabled formation of the normal Ca2+-dependent cluster involving multiple acidic amino acids in the EGF6 region, resulting in a changed structure that thrombin was unable to bind. Recently, Urano et al. analyzed the activation of TAFI by plasma TM and thrombin, using a tPA-induced plasma clot lysis time assay combined with a TAFIa inhibitor and rhsTM that they developed. They demonstrated that TAFI was not activated in the plasma of a TM-Nagasaki patient, but that minute amounts of rhsTM added to the patient’s plasma were sufficient to activate TAFI and inhibit fibrinolysis.27) These results suggest that TM-bound thrombin-dependent TAFI activation in plasma inhibits bleeding and may play a role in physiological thrombus formation.

Position of the G412 residue in the EGF5-6 module of a TM-Nagasaki molecule, analyzed using a CG molecular model (Ref. 26). (A) Ribbon model of the thrombin-TM-EGF4-6 module (TME456) complex (Ref. 25). (B) Ribbon model of thrombin and the TM-EGF5 module (TME5) and molecular surface model of the TM-EGF6 module (TME6). (C) Cluster model consisting of a Ca2+ ion and surrounding amino acids in a TM-EGF5-6 module (TME5-6). Abbreviations: EGF: epidermal growth factor TM: thrombomodulin.

In addition, thrombin binds to chondroitin sulfate in the D3 domain of TM at a different site from exosite 1 and is quickly inhibited by antithrombin.28) This TM-bound thrombin is not involved in the activation of PC or TAFI, and its physiological function remains unknown.

It is presumed that humans with congenital TM homozygous (-/-) deficiency will not survive to birth and will die in embryo. Very rarely, congenital TM heterozygous (-/+) deficiency is found as an atypical form of hemolytic uremic syndrome.29) TM knockout mice (-/-) grow until a gestational age 7.5 days but show abnormal morphology by gestational age 9.5 days and disappear by day 10.5, indicating that TM is necessary for the interaction between the mother’s womb and the embryo.30) It should be noted that endothelial PC receptor (EPCR) knockout mice (-/-), like TM knockout mice, grow up to gestational age 7.5 days, but die at 10.5 days; thus, EPCR is also important for fetal development and may play a key role in preventing thrombosis at the maternal-embryonic interface.31)

6.2. Promotion of thrombin-mediated PC activation by TM: mechanisms of PC activation and APC-mediated anticoagulation.TM increases the rate of PC activation by thrombin more than 1,000 times. Thrombin binds to the EGF5-6 region of TM through exosite 1, and the conformation around the active center of thrombin changes, increasing its affinity for the substrate PC. The Asp349 residue in the EGF4 region of TM plays a role in its Ca2+-mediated binding to PC.32) This PC activation is further promoted in the presence of EPCR (23.1kDa) on vascular endothelial cells.33) TM and EPCR are in close proximity within caveolae on the cell membrane, and PC binds to EPCR and the EGF4 region of TM via the Gla domain of PC in a Ca2+-dependent manner and is rapidly activated by thrombin. This PC activation reaction is further promoted by platelet factor 4 (PF4) (7.8 kDa) derived from activated platelets.34) PF4 is considered to increase the affinity of PC for TM by binding to the chondroitin sulfate sugar chain in the TM-D3 and Gla-domain of PC.

APC specifically inactivates coagulation factors Va and VIIIa through limited proteolysis. For expression of the physiological anticoagulant effect of APC another Gla-containing protein, protein S (PS) (84 kDa), is required as a cofactor for APC. PS promotes the inactivation of factors Va and VIIIa by APC in the presence of phospholipids35) and platelets.36) In this reaction, the APC light chain binds to the EGF1 and EGF2 domains of PS, which is linked to cell membrane phospholipids via the Gla domain. APC then inactivates factors Va and VIIIa by binding to another region of PS.37) This APC cofactor activity of PS is detected only in free PS and not in PS bound to C4b-binding protein with a β-chain (C4BPα) (570 kDa), which consists of seven α-chains and one β-chain.38) C4BPβ, a regulator of the complement system, is thought to sterically hinder the interaction between PS and APC, as well as those with factors Va or VIIIa. C4BPβ is produced in the liver and its plasma concentration increases when the body is inflamed; thus, the APC cofactor activity of PS decreases during inflammation. In addition to its role in APC cofactor activity (inactivating factors Va and VIIIa), PS also promotes tissue factor pathway inhibitor-dependent inhibition of factor Xa in the TF/factor VIIa/factor Xa complex during the initiation of extrinsic blood coagulation.39)

Congenital PC homozygous (-/-) deficiency in humans40) or compound heterozygous protein C deficiency, such as PC-Mie deficiency,41) causes a hypercoagulable state, leading to DIC symptoms (purpura fulminans) shortly after birth. Patients with congenital PC heterozygous (+/-) deficiency or PC molecular abnormalities (patient’s PC activity value / normal person’s PC activity value < 50%) [2] are at risk of developing venous thrombosis as they age. In addition, PC knockout mice (-/-) develop thrombosis and give birth to either stillborn offspring or those that die within 24 hours after birth.42)

Congenital PS homozygous (-/-) deficiency in humans causes thrombosis and stillbirth and, in rare cases, babies born with DIC symptoms called purpura fulminans.43) Patients with congenital PS heterozygous (+/-) deficiency (PS activity value of patient / PS activity value of healthy individual < 50%) [3], or those with PS molecular abnormality typified by protein S-Tokushima,44) have a higher incidence of venous thrombosis as they age. Dysfunction of the protein S-Tokushima molecule is caused by the loss of APC cofactor activity due to mutation of Lys-155 residue to Glu in the second EGF-like domain of the PS molecule, which is the APC binding site.45) Epidemiological analysis revealed that the PS-Tokushima mutation is a genetic risk factor for venous thromboembolism in Japanese people.46) In addition, all PS knockout mice (-/-) develop thrombosis during the fetal period and die in the late embryonic period.47)

6.3. EPCR-dependent anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects of APC.APC-bound to EPCR on vascular endothelial cells activates PAR1, suppresses inflammation of endothelial cells stimulated by LPS and thrombin, and suppresses apoptosis of inflammatory cells. APC-bound to EPCR cleaves PAR1 at the Arg46-Asn47 site, which is different from the thrombin cleavage site. As a result, phosphorylation of p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, which are involved in intracellular inflammation, is suppressed, and activation of transcription factors early growth response protein-1 and NF-κB are also suppressed.48) APC also protects cells from inflammatory disorders by suppressing the expression of apoptosis-related genes such as p53 and transient receptor potential melastatin 2, and increasing the expression of B-cell/CLL lymphoma-2, inhibitor of apoptosis, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen.49) Furthermore, the activation pathway of APC-EPCR-PAR1 exerts anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects by inhibiting Ras homolog family member A, promoting the Ras-related C3 botulinus toxin substrate 1-mediated protective signaling pathway, and transactivating the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 to increase barrier permeability.50) Additionally, APC inhibits neutrophil extracellular trap formation (NETosis), which causes thrombosis and inflammation if excessively developed, by degrading extracellular histones, a major component in the induction of NETosis. This inhibition of NETosis by APC has been suggested to be dependent on neutrophil EPCR, protease-activated receptor 3, and macrophage-1 antigen.51)

Gur-Cohen et al. investigated the roles of PAR1 signaling triggered by thrombin or APC-EPCR in adult bone marrow long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) in mice.52) They revealed that thrombin-PAR1 signaling induced NO production, leading to TNF-α converting enzyme-mediated EPCR shedding and rapid stem and progenitor cell mobilization. Conversely, bone marrow blood vessels provide a microenvironment enriched with PC that retain EPCR+-LT-HSCs by limiting NO generation. Inhibition of NO production by APC-EPCR-PAR1 signaling reduced progenitor cell egress, increased NOlow bone marrow EPCR+ LT-HSCs retention, and protected mice from chemotherapy-induced hematological failure and death. The results suggest roles for PAR1 and EPCR that control NO production to balance maintenance and recruitment of bone marrow EPCR+ LT-HSCs with clinical relevance.

Meanwhile, we studied the effects of APC on bone formation and metabolism. The results revealed that APC promotes osteoblast proliferation via EPCR.53) In this action, APC promoted the phosphorylation of p44/42 MAP kinase in osteoblasts, and this effect was inhibited by an anti-EPCR antibody. In contrast, APC suppressed receptor activator of NF-κB ligand-induced osteoclast differentiation via EPCR, PAR1, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1, and apolipoprotein E receptor 2.54)

Apart from APC, coagulation factor VIIa has been found to attenuate TNF-α- and LPS-induced inflammation, both in vitro and in vivo, via an EPCR-dependent mechanism. Factor VIIa-EPCR-PAR1-mediated anti-inflammatory signaling transmits through the β-arrestin-1-dependent pathway.55)

In contrast, it was reported that APC binds to neutrophil β1/β3 integrin in an EPCR-independent manner and inhibits neutrophil activation during inflammation.56) APC also binds directly to CD11b/CD18 integrin of macrophages and inhibits macrophage activation during inflammation.57) Furthermore, APC exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by degrading the inflammation-inducing substance histone H3, which is a nuclear protein and one of the damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from damaged cells in the body.58)

6.4. Promotion of thrombin-mediated TAFI activation by TM.TM promotes thrombin-mediated activation of TAFI (56 kDa), which is the same as procarboxypeptidase B in the blood. In this reaction, thrombin bound to the EGF5-6 region of TM is thought to activate TAFI bound to the EGF3 region of TM. The binding of TAFI to TM is competitively inhibited by PC,59) and the TM-dependent activation of TAFI by thrombin is inhibited by PF4.60) Activated TAFI (TAFIa) excises Lys residues, which are the binding sites for tPA and plasminogen at the C-terminus of the fibrin molecule, and inhibits plasminogen activation by tPA on fibrin and fibrin degradation (fibrinolysis) by plasmin. It is hypothesized that TAFI activation suppresses PC activation, which promotes thrombus formation and stabilization at injured sites, and promotes the repair of injured tissue.

TM inhibits the activation of complement system factors C3 and C5 by thrombin. Additionally, TAFIa, activated by the thrombin-TM complex, excises the C-terminal Arg residue of activated proteases C3a and C5a, which are important for the development of the complement system and act as inflammation-inducing factors. In addition, TAFIa exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by excising and inactivating the C-terminal Arg residue of bradykinin, which is an inflammation-inducing and vascular permeability-promoting factor.61) Therefore, TM is thought to play a role in maintaining fibrin clots at injury sites and providing anti-inflammatory effects through the activation of TAFI by thrombin, thereby promoting tissue repair. TAFIa in the blood is rapidly inactivated proteolytically by thrombin and plasmin.

6.5. Anti-inflammatory, cell protection, and tissue repair effects of TM itself. 6.5.1. TM inhibits LPS binding to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/CD14.LPS, which is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern, induces inflammatory cell damage by binding to TLR4/CD14 on the membranes of vascular endothelial cells, monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, etc. In response to LPS associated with an infection, the C-type lectin-like structure region in the D1 domain of TM recognizes and binds the Lewis Y antigen of LPS with high affinity,62) thereby inhibiting the binding of LPS to TLR4/CD14.63) This makes TM exhibit anti-inflammatory effects.

6.5.2. TM inhibits the binding of HMGB1 and histone to cell receptors.Nuclear chromatin binding proteins, high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), and histones (H3 and H4), which are included in DAMPs, bind to TLR4 and other receptors in the vascular endothelial cells and activate pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species and activation of NF-κB, which induces cellular inflammatory damage. In response to damage caused by DAMPs, the C-type lectin-like domain of TM-D1 binds with high affinity to HMGB164) and promotes the degradation of HMGB1 by thrombin.65) In this way, TM inhibits the binding of HMGB1 to cell membrane receptors and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects. Moreover, recombinant TM, with chondroitin sulfate in TM-D3, suppresses histone-induced NET formation.66)

6.5.3. TM inhibits leukocyte adhesion to, and activation of, vascular endothelial cells.Leukocytes bind to adhesion molecules on vascular endothelial cells activated by inflammatory stimuli via L-selectin, lymphocyte-function-associated antigen-1 (also known as αLβ2 integrin or CD11a) and macrophage-1 antigen (αMβ2 integrin), amplifying the inflammatory response. In this reaction, TM binds to the Lewis Y antigen of intercellular adhesion molecule 2 through the D1 region,67) or to β2 integrin through the D3 region,68) inhibiting the binding of leukocytes to vascular endothelial cells and suppressing inflammation.

6.5.4. TM inhibits vascular endothelial inflammation mediated by G-protein coupled receptor 15.The vascular endothelial protective effect of TM involves inhibition of apoptosis, suppression of vascular hyperpermeability, and angiogenesis by the promotion of endothelial cell proliferation. Ikezoe et al. found that recombinant TM alleviates mouse graft-versus-host disease in association with an increase in the proportion of regulatory T cells in the spleen.69) Successively they demonstrated that TM-mediated angiogenesis and the cytoprotective function are exerted by binding of the EGF5 region of TM-D2 to G-protein coupled receptor 15 in endothelial cells using recombinant TM-EGF5 protein.70)

APC is not inhibited by AT but is specifically inhibited by PCI (57 kDa), which we discovered and isolated from human plasma,71) by forming an APC-PCI complex in the presence of heparin (Fig. 5).72) Structural analysis of PCI showed that it is a member of the plasma SERPINs.73) PCI also inhibits the thrombin-TM complex, an activator for PC and TAFI, in the presence of heparin.74) The mechanism of PCI inhibition of the thrombin-TM complex is hypothesized to be that thrombin binds to the EGF5-6 region of TM at exosite 1, changes its conformation around the active center, interacts specifically with the reactive site of PCI, and forms a complex with PCI.

(A) Surface model of an APC-PCI complex. Heparin is considered to promote complex formation by binding to the basic residues in the 37-loop structure (Lys37-Lys38-Lys39) (blue) of APC (green) and Arg269-Lys270 on the H-helix region (blue) of PCI (gray) and crosslinking both molecules (Ref. 72). (B) Molecular modeling of the reactive center loop region of PCI with the 37-loop of APC. The active center of the APC (green) and the reactive center of PCI (gold) are shown as ribbon models. Hydrogen atoms are not shown for clarity. The distances from Arg362 of PCI to Lys37 and Lys39 of APC in APC-PCI are estimated to be 6.8 Å and 5.6 Å, respectively, in the absence of heparin. These distances are estimated to be smaller in the presence of heparin (Ref. 80). Abbreviations: APC, activated protein C, PCI: protein C inhibitor.

In addition, PCI is the same substance as plasminogen activator inhibitor-3, which is a physiological inhibitor of urinary-type plasminogen activator (uPA). PCI is currently referred to as SERPINA5 by the international nomenclature committee. Similar to AT (SERPINC1), the reactive site of PCI undergoes a conformational change in the presence of negatively charged substances, such as heparin, and readily interacts with the active site of proteases such as APC and thrombin bound to TM.

APC-PCI complex levels are increased in the plasma of patients with various thrombotic diseases.75)-77) As described above, PCI inhibits the thrombin-TM complex and regulates the TM-PC anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory/cytoprotective pathway. PCI is produced in many tissues of the body, such as the kidney, liver, and reproductive system tissues, and may play a role in a variety of organ-specific functions.

PCI, produced in the proximal tubule of the kidney, regulates uPA and may prevent tissue damage caused by uPA. Because uPA levels are increased in renal cell carcinoma (RCC), we compared PCI expression levels in RCC tissues with those in nontumor kidney tissue of humans. The PCI antigen levels and PCI mRNA levels expressed in RCC tissues and cell lines were significantly lower than those in nontumor kidney tissues and normal renal proximal tubular epithelial cells, suggesting that PCI regulates uPA-induced cancer cell invasion and may be a potential therapeutic agent for inhibiting renal tumor invasion.78)

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which plays a role in the proliferation of hepatocytes, is converted into an active form by a serine protease HGF activator (HGFA) which is activated from pro-HGFA by thrombin. We found that PCI inhibits HGFA to form a complex independent of heparin. Plasma PCI levels in human liver donors decrease rapidly after hepatectomy. Concomitant with the decrease in plasma PCI levels, pro-HGFA and HGFA-PCI complex levels increase significantly, peaking 12 h after surgery (with pro-HGFA levels increasing 3-fold and HGFA-PCI complex levels increasing 1.5-fold compared with preoperative levels). Subsequently, both pro-HGFA and HGFA-PCI complex levels gradually decrease.79) These clinical results suggest that during the process of tissue regeneration, thrombin generated at the site of tissue injury stimulates hepatocytes via PAR1, resulting in increased levels of pro-HGFA and HGFA and the formation of HGFA-PCI complexes (Fig. 6).80)

Possible mechanism of PCI-mediated tissue regeneration control via HGFA and the TM-PC pathway. During the process of tissue regeneration, thrombin generated at the site of tissue injury stimulates hepatocytes through PAR1, resulting in the production of Pro-HGFA. Thrombin activates Pro-HGFA and activated HGFA proteolytically activates the HGF precursor to generate the active form of HGF that guides tissue regeneration. Thrombin also activates PC in the presence of TM, and the generated APC promotes tissue regeneration. PCI inhibits HGFA in the absence of heparin (liquid phase) and regulates the thrombin-TM complex and APC in the presence of heparin-like proteoglycan in the TM-PC system (solid phase), suppressing excessive tissue production. Human pro-HGFA production in the hepatocytes requires PKC activation and Sp1 and AP2 transcription factors (Ref. 80). Abbreviations: APC: activated protein C, HGFA: hepatocyte growth factor activator, PC: protein C, PCI: protein C inhibitor, PKC: protein kinase C, Sp1: specificity protein 1, TM: thrombomodulin.

In humans, PCI is expressed in various tissues and is present in many body fluids, such as plasma and seminal fluid. In contrast, in mice, PCI is expressed only in the reproductive tracts and is absent from plasma. Therefore, we created human PCI gene transgenic (hPCI-Tg) mice.81) In these mice, similar to humans, human PCI is expressed in nearly all tissues and organs. We used hPCI-Tg mice to characterize the physiological and pathological roles of PCI in the body. For example, we confirmed that PCI acts as a potent inhibitor of HGFA and APC in plasma and/or at the site of tissue injury, playing a role in regulating tissue regeneration in the hPCI-Tg mouse model.80)

PCI homozygous (-/-) deficiency has not been found in humans; therefore, reduced expression of the PCI gene may lead to fatal symptoms. In mice, PCI is produced only in the reproductive tract, and PCI knockout male mice have reduced spermatogenesis and are infertile,82) suggesting that PCI plays a major role in regulating male reproductive function. PCI is present in the acrosome of the sperm and inhibits the action of acrosin, a trypsin-like protease that acts when the sperm enters the egg membrane.83) During fertilization, PCI dissociates from the acrosin, allowing sperm to enter the egg. Additionally, PC in the seminal vesicle glands binds to semenogelin, a gelatinous coagula protein. Semenogelin released into seminal fluid though ejaculation is degraded by prostate-specific antigen, a protease derived from the prostate gland, increasing the mobility of sperm ejected from the epididymis.84) It is assumed that PCI, which is released into seminal fluid along with semenogelin, plays a role in controlling sperm motility by inhibiting excessive degradation of semenogelin by prostate-specific antigen.

The structure-function relationship of PCI, inhibited proteases, genetic structure, evolutionary lineage of PCI in various species, vascular permeability and tumor inhibition effects, and the diverse effects of PCI obtained using hPCI-Tg mice are described in a previous review article.85)

TMα, a formulation of rhsTM, was developed as a treatment for DIC. However, rhsTM has also been studied in animal and cell models of various thrombotic and inflammatory diseases. Table 1 summarizes examples of experimental studies where treatment with rhsTM showed improvement in pathological conditions. These included a suppressive effect on vascular thrombosis,86) TF-induced DIC,87) LPS-induced sepsis,88) growth of malignant tumor cells,89) and tissue invasion of tumor cells90),91); a promotive effect on repairing damaged tissue92); a suppressive effect on atherosclerosis93) and inflammatory vascular lesions, and vascular fibrosis and necrosis in Kawasaki disease94); a suppressive effect on graft-versus-host disease,69) monocrotaline-induced sinusoidal obstruction syndrome,95) and cyclosporine A-induced vascular hyperpermeability96); a suppressive effect on apoptosis of pancreatic β cells in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy97); functional improvement of post-ischemia-reperfusion disorders in various organs98)-100); and a suppressive effect on pre-eclampsia,101) interstitial pulmonary fibrosis,102) and asthma.103) These pathology-ameliorating effects of rhsTM suggest that TM is of great physiological importance for maintaining microcirculatory homeostasis in various organs.

Examples of research showing the effectiveness of rhsTM treatment using disease model animals and cells

| Pathological conditions | Animal or cell models for elucidating the pathology | References |

|---|---|---|

| Thrombotic disease | Thrombin-induced vascular and tissue thrombosis in mice | 86 |

| DIC | Tissue factor-induced DIC in rats | 87 |

| Sepsis | LPS-induced sepsis model in mice | 88 |

| Malignant tumor growth | Human pancreas cancer cell proliferation in mice | 89 |

| Malignant tumor invasion | Mouse melanoma cell invasion in mice | 90 |

| Malignant tumor invasion | Human breast cancer cell invasion in cultured cells | 91 |

| Wound healing | Mouse corneal epithelial cell repair in mice and cells | 92 |

| Atherosclerosis | Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice | 93 |

| Kawasaki disease | CAWS-induced vascular fibrinoid necrosis in mice | 94 |

| Transplant-related disorders | Hematopoietic cell transplant-induced GVHD in mice | 69 |

| Vascular endothelial disorder | Monocrotaline-induced SOS in mice and HUVECs | 95 |

| Vascular hyperpermeability | CsA-induced vascular permeability in endothelial cells | 96 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | Glucose-induced epithelial apoptosis in mice | 97 |

| Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury | Ischemia kidney reperfusion injury in rats | 98 |

| Liver ischemia-reperfusion injury | Liver ischemia reperfusion injury in mice | 99 |

| Cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury | Cardiopulmonary bypass in rats | 100 |

| Preeclampsia | L-NAME-induced preeclampsia in rats | 101 |

| Interstitial pulmonary fibrosis | Bleomycin-induced lung injury model in mice | 102 |

| Asthma | Ovalbumin-induced asthma model in mice | 103 |

Abbreviations: rhsTM: recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin, DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation, LPS: lipopolysaccharide, CAWS: Candida albicans water-soluble fraction, GVHD: graft versus host disease; SOS: sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, CsA: cyclosporin A, HUVECs: human umbilical vein endothelial cells, L-NAME: N(γ)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester.

A 1998 epidemiological survey, conducted by the former Ministry of Health and Welfare research group, reported that the annual number of patients with DIC in Japan was approximately 73,000, with a mortality rate of 56.0%. A subsequent 2009 nationwide epidemiological survey, conducted by the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis, reported that the number of patients developing DIC had not changed much in 10 years, but that the mortality rate had decreased to 40.0%. Despite this improvement, compared with other diseases, patients with DIC still have a very high mortality rate.

TMα was found to have a higher rate of DIC resolution compared with that of heparin in a phase III clinical trial104) targeting patients with DIC due to hematopoietic malignancies and infectious diseases, based on the former Ministry of Health and Welfare DIC diagnostic criteria. TMα was approved in January 2008 and launched in May of the same year.

For adults, TMα is usually administered as an intravenous infusion of 380 units/kg once a day over approximately 30 minutes. For patients with severe renal dysfunction, the dose may be reduced to 130 units/kg as appropriate, depending on symptoms.

9.1. Verification results of post-marketing all-case surveillance.A post-marketing survey was conducted of patients with DIC treated with TMα, registered from May 2008 to April 2010, and the analyzed data were published in 2014.105)-108) The medical departments that used TMα were as follows: emergency department (27.2%), intensive care (16.6%), hematology (25.1%), internal medicine (14.9%), surgery (5.4%), pediatrics (4.1%), and other departments (6.8%).

The underlying diseases of patients with DIC who received TMα (number of patients treated: 4,062) were infectious diseases (61.9%), hematopoietic tumors (25.4%), solid tumors (2.2%), and other diseases (10.5%). Regarding efficacy, the proportion of patients whose DIC symptoms improved (improvement rate) was 72,6% in all cases (breakdown: 71.0% for infections, 78.1% for hematopoietic tumors, 46.8% for solid tumors, and 73.4% for others). The proportion of patients with resolution of DIC (resolution rate) was 57.0% in all cases (breakdown: 58.7% for infections, 56.2% for hematopoietic tumors, and 59.2% for others). The proportion of patients who were alive 28 days after the end of treatment (survival rate) was 65.9% for all cases (breakdown: 64.4% for infections, 71.0% for hematopoietic tumors, 42.0% for solid tumors, and 67.3% for others).

Regarding side effects, the proportion of patients who experienced side effects upon first treatment (side effect incidence rate) was 6.9% in all cases, with 5.3% of all patients experiencing bleeding side effects. The proportion of patients who developed hemorrhagic side effects by day 7 of treatment was 4.8% of patients with DIC due to infectious diseases and 3.8% of patients with DIC due to hematopoietic tumors. These results were lower than the 14.0% for patients with DIC due to infectious diseases and 10.9% for patients with DIC due to hematopoietic tumors in the phase III trial.104)

Based on these results, the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis published an 2014 Expert consensus for the treatment of DIC in Japan,109) which added TMα, which was not included in the 2010 Expert consensus for the treatment of DIC in Japan,110) as a new recommended treatment for DIC.

9.2. Clinical effects of TMα on septic DIC.In septic DIC, TF and PAI-1 released from immune cells (monocytes and neutrophils) and injured cells, along with nuclear proteins such as HMGB1 and histones, cause significant vascular endothelial damage. The coagulation system becomes hyperactive, the fibrinolytic system is suppressed, and microcirculatory disorders caused by systemic microthrombi cause multiorgan damage.

In Europe and the United States, the concept of DIC has historically been underemphasized for coagulopathy associated with sepsis, and anticoagulant therapy is not particularly recommended in the surviving sepsis campaign guidelines revised in 2021. In contrast, in Japan, anticoagulant therapy has been actively used for septic DIC.

A subgroup analysis of a domestic multicenter observational study, reported in 2015,111) showed that in patients with particularly severe septic DIC (acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II [APACHE II] score: 24-29; hazard ratio: 0.281; (OR [95% confidence interval]: 0.093 to 0.850; p = 0.025), TMα treatment was effective in improving survival. These results indicated that the effectiveness of anticoagulants for septic DIC varies from patient to patient, and that TMα is effective in severe cases.

In the SCARLET (Sepsis Coagulopathy Asahi Recombinant LE Thrombomodulin) trial, which included 800 patients with sepsis-associated coagulopathy, treatment with TMα, compared with that of placebo, did not significantly reduce 28-day all-cause mortality (26.8% in the TMα group vs 29.4% in the placebo group).112) In response to this result, Yamakawa et al.113) performed an updated meta-analysis by replacing the SCARLET results with a subgroup analysis of the proportion that still met coagulopathy criteria at the time of treatment. The results showed that TMα treatment significantly reduced the risk of mortality (risk ratio, 0.82; OR: 0.69-0.98; p = 0.03).

The Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock (J-SSCG) have recommended anticoagulant therapy for septic DIC since the first edition in 2012, and the latest J-SSCG 2024 continues to endorse TMα as a weak antithrombin drug. Among these, the beneficial effects observed in the TMα treatment group were a reduction in mortality rate (39 fewer deaths per 1000 patients compared with the placebo or non-TMα treatment groups) and resolution of DIC (120 fewer deaths per 1000 patients). However, adverse events included an increase in bleeding complications (12 more cases per 1000 patients). Despite these risks, the administration of TMα was weakly recommended, based on a relative comparison of benefits and harms.

9.3. Clinical effects of TMα on hematopoietic tumor DIC.In DIC due to hematopoietic tumors, hypercoagulability is activated by TF and factor Xa-like cancer procoagulants released by leukemia cells; in particular, acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells often cause bleeding symptoms due to increased fibrinolysis associated with plasmin production induced by excessive expression of annexin II.

Matsushita et al.114) analyzed data from 172 patients with DIC caused by APL and found that 24 patients (14.0%) died within the first 30 days, with 12 of them (7.0%) experiencing severe bleeding. Of the 49 patients who received TMα before starting leukemia treatment, only one experienced an early hemorrhagic death. They reported that early TMα treatment reduced early hemorrhagic mortality and improved coagulopathy, with or without the concomitant use of all-trans retinoic acid.

Takezoko et al.115) administered anticoagulant therapy to 47 patients who developed DIC out of 103 patients with acute myeloid leukemia, excluding APL, and found that the survival rate was significantly higher in the TMα treatment group than that in the low molecular weight heparin treatment group (log-rank test, p =0.016).

Ikezoe et al.116) compared patients with APL who developed DIC and were treated with conventional therapy all-trans retinoic acid or chemotherapy (control group: 8 cases) and patients who received TMα in addition to conventional therapy (TMα group: 9 cases). They found that DIC resolution was observed significantly earlier in the TMα-treated group compared with the control group (log-rank test, p =0.019).

In 2024, Kawano et al.117) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective (1 report, 64 cases) and retrospective studies (7 reports, 209 cases), searching PubMed, Cochrane, and Scopus for recovery from DIC, adverse events, and overall survival of patients with DIC associated with hematopoietic tumors who received TMα from April 2008 to April 2023. TMα treatment showed a high rate of recovery from DIC (OR: 2.25 [1.09-4.63] and 1.98 [1.12-3.50] in prospective and retrospective studies, respectively) and a decrease in hemorrhagic adverse events (OR: 0.83 [0.30-2.30] and 0.21 [0.08-0.57]). In contrast, although TMα treatment did not improve overall survival (OR: 1.06 [0.42-2.66] and 1.72 [0.87-3.39]), the incidence of death due to cerebral hemorrhage was extremely low (0 out of 94 patients). Based on these results, they concluded that the use of TMα in patients with DIC due to hematopoietic tumor is effective and safe.

9.4. Clinical effects of TMα on DIC associated with solid tumors.In DIC associated with solid tumors, hypercoagulation is caused by inflammatory cytokines and TF released by cancer cells, DAMPs derived from necrotic cancer cells associated with anticancer drug treatment, and pathogen-associated molecular patterns derived from pathogens associated with infection. Hypercoagulation causes bleeding symptoms due to consumption of coagulation factors, and various pathologies are observed depending on the type of the type of cancer and the stage of progression.

Tamura et al.118) conducted a post-marketing clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TMα in patients with DIC due to solid tumors (101 cases; 60% of all patients had lung, stomach, and breast cancers). The DIC resolution rate at the end of TMα treatment was 34.0%, with 55.2% of patients showing improvement in the DIC score and 22.9% exhibiting worsening of the DIC score. The overall survival rate on day 28 after the start of TMα treatment was 55.4%, and the survival rate in patients who had resolution of DIC was 90.9%. The incidence of bleeding associated with TMα treatment was 12.9% by day 28, but no severe bleeding cases occurred. From these results, they concluded that TMα treatment is effective and safe for DIC associated with solid cancers.

Ouchi et al.119) reported on a retrospective analysis of patients with DIC due to solid tumors (123 cases; the underlying diseases were gastric cancer in 31.7%, colorectal cancer in 20.3%, pancreatic cancer in 9.8%, biliary tract cancer in 8.1%, esophageal cancer in 7.3%, and other cancers in 22.8%) who were treated with TMα from 2009 to 2016 at a cancer center hospital. The median overall survival for all patients was 41 days (range: 1-957 days) and the DIC resolution rate was 35.2%. The DIC score and DIC-related blood test results (fibrin degradation products and prothrombin time-international normalized ratio) at the end of TMα treatment were significantly improved (p < 0.001). The overall survival of patients who received chemotherapy after DIC onset was longer than that of patients who did not receive chemotherapy (median, 125 days vs. 11 days, p = 0.001). In both univariate and multivariate analyses, chemotherapy treatment after the onset of DIC was associated most strongly with overall survival. Based on these results, they stated that if TMα treatment improves DIC status while treating the underlying disease, survival times for patients with DIC due to solid tumors may be extended.

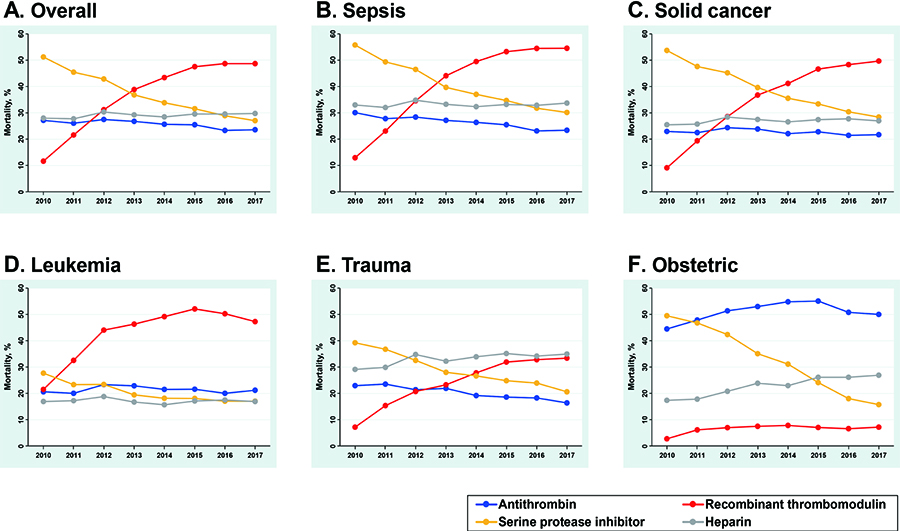

9.5. Trends in DIC outcomes and therapeutic drug selection in Japan.Yamakawa et al.120) conducted a retrospective observational study on the trends in the clinical data of adult patients with DIC (total 325,327 cases) who were treated from July 2010 to March 2018 at over 1,200 emergency hospitals in Japan. They analyzed pathological characteristics, including changes in the median age of patients, worsening of comorbidities, disease severity, and changes in the usage status of anticoagulants (heparin, SERPINs, antithrombin, and TMα) used for DIC treatment during the period. The main underlying diseases in the development of DIC were sepsis, solid tumors, leukemia, trauma, and obstetric diseases, and during this period, the overall 28-day mortality rate of patients with DIC ranged from 41.8% (95% CI: 41.2%-42.3%) to 36.1% (95% CI: 35.6%-36.6%), representing a 14% decrease over 8 years (Ptrend < 0.001). The downward trend in mortality was particularly pronounced for patients with sepsis and leukemia (15% and 14% reductions, respectively). In contrast, no clinically meaningful changes in mortality were observed in patients with trauma or obstetric diseases. During this period, major bleeding events increased from an average of 8% to 10%, but the length of hospital stay shortened from an average 44 days to 40 days.

Figure 7 shows changes in the breakdown of anticoagulants used in patients with DIC during this period.120) The usage rate of heparin remained unchanged, at approximately 30%, from 2010 to 2017. The usage rate of SERPINs was 51.2% in 2010, but rapidly decreased to 27.0% in 2017. The usage rate of antithrombin was 27.1% in 2010 and decreased slightly to 23.6% in 2017. In contrast, in 2010, the usage rate of TMα was 11,6% in all patients, 12.9% in patients with sepsis, 9.1% in patients with solid tumors, and 21.5% in patients with leukemia. By 2017, the usage rate of TMα had increased to 48.7% in all patients, 54.6% in patients with sepsis, 49.7% in patients with solid tumors, and 47.3% in patients with leukemia, showing a year-by-year increase. These results indicated that the trend toward lower mortality rates and shorter hospital stays in patients with DIC due to sepsis and leukemia may be associated with increased use of TMα.

Time trends of anticoagulant usage for patients with DIC, 2011-2017. (A) Overall, (B) patients with sepsis, (C) patients with solid cancer, (D) patients with leukemia, (E) patients with trauma, and (F) patients with obstetric disease (Ref. 120). Abbreviation: DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation.

The factors included in the TM-PC anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory/cytoprotective pathway are involved in maintaining blood flow throughout the body, particularly in the microcirculation system of all organs, enabling each organ to perform its functions. This system also plays an important role in the regeneration and repair of injured tissues, making it the most important control system that maintains homeostasis in living organisms. As discussed in the main text, TM has diverse functions within its molecule, and studies using disease model animals and cells have shown that rhsTM has therapeutic effects on various pathological conditions that do not involve DIC. Experimental studies using rhsTM in vitro and in vivo suggest new, previously unanticipated TM functions. Therefore, TMα holds potential as a future therapeutic agent for various pathological conditions resulting from disruptions in microcirculatory system homeostasis.

TMα was developed as a DIC treatment alternative to heparin, and more than 16 years after its release, TMα has demonstrated improvement in DIC caused by diseases such as sepsis, solid tumors, hematopoietic tumors, and trauma. This has been evaluated in many clinical studies, and its effectiveness is highlighted in DIC clinical practice guideline.110),121) However, since there are various underlying diseases that cause DIC, including cases where DIC develops due to infection in patients with malignant tumors and cases where DIC develops due to unknown causes, the method of using TMα requires further study in the future.

The author would like to thank all research collaborators at the Department of Molecular Pathobiology, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu-city, the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Suzuka University of Medical Science, Suzuka-city, and Asahi Kasei Pharma Co. Ltd, Tokyo. Most of the research costs in the author’s laboratory are covered by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from MEXT/JSPS. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K08850. The author would like to thank Asahi Kasei Pharma for providing rhsTM and information on the clinical results of TMα. The author also thanks Editage for English language editing.

This review is based in part on my review published in a Japanese journal cited in Ref. 122.

Edited by Shizuo AKIRA, M.J.A.

Correspondence should be addressed to: K. Suzuki, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Suzuka University of Medical Science, Minamitamagaki-cho 3500-3, Suzuka, 513-8670 Mie, Japan (e-mail: suzukiko@suzuka-u.ac.jp).

activated protein C

APLacute promyelocytic leukemia

ATantithrombin

C4BPβC4b-binding protein with a β-chain

DAMPdamage-associated molecular pattern

DICdisseminated intravascular coagulation

EGFepidermal growth factor

EPCRendothelial protein C receptor

FDPfibrin degradation products

Glaγ-carboxyglutamic acid

HGFhepatocyte growth factor

HGFAhepatocyte growth factor activator

HMGB1high-mobility group box 1

hPCI-Tghuman protein C inhibitor gene transgenic

ILinterleukin

J-SSCGThe Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock

KLF2Krüppel-like factor 2

LPSlipopolysaccharide

LT-HSCslong-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells

NDRG-1N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1

NETosisneutrophil extracellular trap formation

NF-κBnuclear factor κB

NOnitric oxide

PAIplasminogen activator inhibitor

PAR1protease-activated receptor 1

PCprotein C

PCIprotein C inhibitor

PF4platelet factor 4

PSprotein S

RCCrenal cell carcinoma

rhsTMrecombinant human soluble thrombomodulin

SERPINserine protease inhibitor

Sp1specificity protein 1

TAFIthrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor

TFtissue factor

TFPItissue factor pathway inhibitor

TLR4Toll-like receptor 4

TMthrombomodulin

TMαrecombinant TM drug

TNFtumor necrosis factor

tPAtissue-type plasminogen activator

uPAurinary-type plasminogen activator

Koji Suzuki was born in Shizuoka prefecture, Japan, in 1947. He graduated from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Osaka University in 1969, and received his PhD degree from Osaka University in 1974. After working at the Protein Research Institute, Osaka University, he became Associate Professor of the Clinical Laboratory at Mie University Hospital in 1977. From 1980 to 1982, he studied in the laboratory of Dr. Johan Stenflo at Lund University, Sweden. In 1989, he became Professor of the Enzyme Research Institute, Tokushima University. In 1991, he became Professor of the Department of Molecular Pathobiology at Mie University School of Medicine. From 2009 to 2011, he served as Vice President for Research of Mie University and was then appointed Professor Emeritus of Mie University. Since April 2011, he has served as Professor of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Vice President for Research at Suzuka University of Medical Science.

He has primarily studied the molecular mechanisms involved in blood clotting and the thrombomodulin (TM)-protein C (PC) anticoagulation and anti-inflammatory pathways. In particular, he and his colleagues were the first to isolate and sequence-analyze a cDNA clone of human TM and developed recombinant TM as a treatment for disseminated intravascular coagulation. He also discovered the PC inhibitor and elucidated its structure and pathophysiological functions and studied the molecular pathobiology of congenital and acquired thrombosis disorders, including PC deficiency, protein S deficiency, and TM deficiency. For these achievements, he was awarded the ISTH Recognition Investigator Award in 2005, the Erwin von Bälz Prize (First Prize) in 2008, the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Award (Research Category) in 2010, the Inoue Harushige Prize of the Japan Science and Technology Agency in 2011, and the ISTH Distinguished Career Award in 2011. His main academic activities to date include serving in the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (former director and advisor), the Japanese Society of Hematology (former director), and the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) (councilor from 2000 to 2006).