2022 Volume 7 Article ID: 20220028

2022 Volume 7 Article ID: 20220028

Objectives : Many stroke patients experience motor and cognitive dysfunctions that make living at home challenging. We aimed to identify the factors associated with hospital discharge to home in older stroke patients in convalescent rehabilitation wards where intensive and comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation are performed following acute-phase treatment.

Methods : A retrospective cohort study was conducted among 1227 older stroke patients registered in the database of the Council of Kaga Local Stroke Network, Japan, between 2015 and 2019. Patients’ basic characteristics, discharge destination, type and severity of stroke, cognitive status, and activities of daily living (ADL) including continence were evaluated.

Results : The proportion of subjects discharged to home was 62.3%. The mean hospital stay in the home discharge group was shorter than that in the non-home discharge group (111 days vs. 144.6 days, P <0.001). The following factors were associated with discharge to home: age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 2.801, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.473, 2.940]; P <0.001), sex (AOR: 1.513, 95% CI [1.112, 2.059]), stroke type (AOR: 1.426, 95% CI [1.013, 2.007]), low cognitive status (AOR: 3.750, 95% CI [2.615, 5.379]), low level of bladder control (AOR: 2.056, 95% CI [1.223, 3.454]), and low level of bowel control (AOR: 2.823, 95% CI [1.688, 4.722]).

Conclusions : Age, sex, stroke type, cognitive function, and ADL scores for bladder and bowel control were associated with discharge to home. Improving continence management regarding both voiding and defecation may be a promising care strategy to promote hospital discharge to home in older stroke patients.

Although the incidence rate of stroke in Japan has been decreasing over the past few decades, it remains relatively high with approximately 220,000 new strokes occurring annually; the total number of stroke patients in Japan is approximately 1.12 million.1,2) This relatively high value is due to social conditions such as the traditional high-salt diet and the aging population. Stroke causes severe damage to the motor and cognitive functions, particularly higher brain function, resulting in impaired activities of daily living (ADL), and many patients become bedridden.3) Therefore, after the acute phase of brain treatment and prevention of recurrence, it is important to enhance ADLs through rehabilitation to avoid patients becoming bedridden and to enable a return to life similar to that before the onset of stroke.4) An important goal of stroke treatment is the patient’s return home from the hospital.

In Japan, the treatment process after the onset of stroke is divided into three phases: the acute phase, the convalescent phase, and the community-based phase.5) Most patients are transferred to inpatient facilities to receive treatment and rehabilitation according to the phase. Patients with mild stroke are usually discharged home after treatment in the acute phase. However, patients with impaired ADLs are often transferred to other medical facilities to provide specialized rehabilitation. After the initial acute phase, a multidisciplinary team provides rehabilitation and care with the aim of home discharge not only in the rehabilitation training room but also in the ward.6,7,8) Many patients aim to return home directly from these convalescent rehabilitation wards. However, approximately 40% of stroke patients are not able to return home from the convalescent rehabilitation ward.5)

Previous studies reported that some factors preventing patients from returning home were female sex,9) advanced age,10,11) stroke severity,12) poor nutrition,13) sarcopenia,14,15) low ADL level before the incidence of stroke,9) cognitive function,4,16) and ADL.11,17) Although ADL is a strong predictor for returning home, patients can return home if appropriate care is available and adjustments have been made to the living environment.9,11,16) One such requirement is the adjustment of the toilet environment, and since the inability to use the toilet independently is also a factor that hinders return to home, it is vitally important to focus on voiding support.

After a stroke, 21–47% of patients experience voiding dysfunction due to central nervous system damage during the early stage of stroke.18) Subsequently, when cerebral edema and other symptoms are alleviated, usually from approximately 6 months following the stroke, the cerebral cortex is unable to inhibit voiding, and this results in storage dysfunction, such as frequency, urgency, and incontinence, due to detrusor overactivity. The incidence of storage dysfunction in stroke patients is high, ranging from 37 to 79%,19) and symptoms persist for a long time, even 1 year after onset.20,21) Storage dysfunction19) and urinary tract infection22) affect the patient’s ability to return home after the acute phase. Voiding behavior17) is another factor. In contrast, during the convalescent phase, when rehabilitation is more advanced, urinary retention23) and having an indwelling urethral catheter24,25) have been shown to interfere with returning home. However, it is unclear whether storage symptoms or impaired ADLs related to urination inhibit returning home from the hospital. Consequently, this study aimed to identify the factors associated with returning home from a convalescent rehabilitation ward.

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted between April 2015 and March 2019. The study population included stroke patients who were registered in the Kaga Regional Cooperation Clinical Pathway for Stroke (KRCCPS) database; Kaga is located in the midwestern region of Japan. The inclusion criteria were (1) patients with cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage; (2) age ≥65 years; and (3) transfer to and discharge from convalescent rehabilitation wards during the study period. The exclusion criterion was patients who died in the convalescent rehabilitation ward.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of Kanazawa University (Review No. 3580–2). Informed consent for this study was not obtained from the patients or their families because they gave written informed consent to use their data for studies before data were recorded at the acute hospital. A research disclosure form was posted on the website of Kanazawa University Hospital to allow the patients and their family members to opt out.

DatabaseWe retrieved data from the KRCCPS database. This database covers 18 acute care hospitals, 11 hospitals with convalescent rehabilitation wards, and 476 facilities for community rehabilitation.26) Data were stored in an Excel sheet by individuals involved in the care of stroke patients, such as physicians, nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and pharmacists. The system has been operational since 2009 and has accumulated data for over 5000 individuals. The types of data recorded have been revised five times to date, with the most recent update being in 2015, which was a major revision. Therefore, data from April 2015 to March 2019 were extracted for this study.

VariablesHospital Discharge DestinationData on the discharge destination from the convalescent rehabilitation ward were collected. The discharge destination was classified as home discharge (i.e., to where the patients lived just before the stroke) or others, including hospitals and nursing homes.

Urination StatusThe location and method of voiding (i.e., toilet, bedside commode, on the bed [diaper or indwelling catheter], and unknown) were extracted before the incidence of stroke, at discharge from the acute ward, and at discharge from the convalescent rehabilitation ward. Multiple locations were checked if patients urinated at different places during daytime and nighttime. For the current study, the location of urination with the worst ADL level was selected from multiple locations.

ADL (Motor and Cognitive Functions)The Functional Independent Measure (FIM) was used to evaluate ADL. FIM comprises 13 items for motor function and 5 items for cognitive function, with a 7-point scale measuring the amount of assistance required. A higher score, particularly those exceeding 5 points for an item, indicates independence in ADL. The validity and reliability of the scale have been confirmed.27,28,29)

The sum of the five cognitive items was used to assess cognitive function in this study. Regarding motor function, the scores of five items of voiding-related behavior were used (i.e., walking, toilet transfer, toileting, bladder control, and bowel control). All scores were obtained at discharge from the acute ward and at discharge from the convalescent rehabilitation ward.

Demographic VariablesAge, sex, stroke type, complications, length of hospital stay, the presence of a caregiver at home, and stroke severity were determined. Stroke severity was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). NIHSS comprises 11 items and is rated on a scale of 0–42 points, with larger scores indicating greater neurological severity. The score at hospitalization in the acute ward was used in this study. mRS evaluates the severity of physical disabilities with each item rating in the range 0–6 points. Higher scores (≥3 points) indicated moderate to severe physical disabilities requiring assistance from caregivers. The scores at discharge from the acute ward and the convalescent rehabilitation ward were used.

AnalysisStudent’s t-test and Pearson’s chi-square test were used to compare the home discharge and non-home discharge groups. To examine factors related to home discharge from the convalescent rehabilitation ward, a binomial logistic regression analysis was used with the forced entry of variables with P <0.05 in the univariate analysis. The adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for home discharge. Before conducting the binomial logistic regression analysis, the multicollinearity of the independent variables was examined. The statistical software package JMP ver. 16 (SAS Institute Japan Ltd.) was used for analysis. Statistical significance was set at P <0.05.

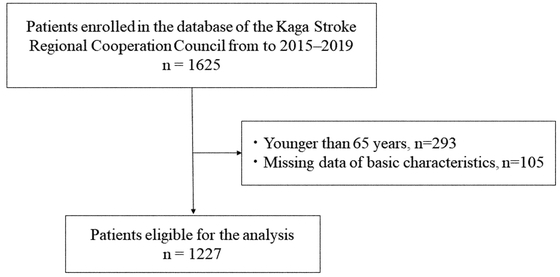

Of the 1625 patients enrolled in the database from 2015 to 2019, 398 were excluded either for being younger than 65 years (n=293) or if data regarding basic characteristics or FIM scores (n=105) were missing. The remaining 1227 subjects were analyzed in this study (Fig. 1). In total, 764 patients were discharged home from convalescent rehabilitation wards (home discharge group), whereas 463 were not (non-home discharge group). In the non-home discharge group, 376 (81.2%) and 85 (17.6%) patients, respectively, were transferred to nursing homes or to hospitals for the community-based phase. The mean length of cumulative hospital stay in the acute and convalescent rehabilitation wards was 111.0 days in the home discharge group and 144.6 days in the non-home discharge group.

Flowchart of patient selection.

Compared with the non-home discharge group, the home discharge group were younger (75.9 ± 7.3 years in the home discharge group vs. 80.6 ± 7.1 years in the non-home discharge group, P <0.001), with a lower proportion of women (42.4% vs. 56.4%, P <0.001), cerebral hemorrhage (28.1% vs. 35.2%, P <0.001), atrial fibrillation (21.3% vs. 30.1%, P <0.001), and constipation (39.2% vs. 45.5%, P=0.036). Regarding stroke severity, the home discharge group had lower NIHSS scores (8.3 ± 6.9 vs. 12.3 ± 8.0, P <0.001) than the non-home discharge group. The proportion of patients in the home discharge group with an mRS score of 3 or more points was lower at admission to the acute ward (90.5% vs. 94.7%, P=0.033), at acute ward discharge (77.2% vs. 95.3%, P <0.001), and at convalescent rehabilitation ward discharge (39.5% vs. 91.2%, P <0.001) than those in the non-home discharge group.

Before the onset of stroke, 93.2% of patients in the home discharge group used the toilet or bedside commode compared with 86.1% in the non-home discharge group (P <0.001). After the onset of stroke, this proportion remained lower than before the onset and was also significantly lower in the home discharge group at two time points, i.e., at acute ward discharge (64.2% vs. 17.8%, P <0.001) and at convalescent rehabilitation ward discharge (86.4% vs. 35.0%, P <0.001). Regarding ADL, total FIM scores at convalescent rehabilitation ward discharge were higher in the home discharge group than in the non-home discharge group; moreover, the total scores for cognitive items (27.7 ± 6.8 vs. 16.9 ± 8.1, P <0.001), bladder control (5.9 ± 1.9 vs. 2.8 ± 2.2, P <0.001), bowel control (6.0 ± 1.7 vs. 3.1 ± 2.3, P <0.001), toileting (5.9 ± 1.7 vs. 2.9 ± 2.1, P <0.001), toilet transfer (6.1 ± 1.4 vs. 3.4 ± 2.1, P <0.001), and walking (5.7 ± 1.8 vs. 2.9 ± 2.1, P <0.001) were significantly higher in the home discharge group (Table 1).

| Home discharge n=764 | Non-home discharge n=463 | P-value | |||

| External variables | Age | 75.9 ± 7.3 | 80.6 ± 7.1 | <0.001 | |

| >75 years | 409 (53.5) | 368 (79.5) | <0.001 | ||

| 65 to <75 years | 355 (46.5) | 95 (20.5) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 324 (42.4) | 261 (56.4) | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 440 (57.6) | 202 (43.6) | |||

| Stroke type | |||||

| Cerebral infarction | 514 (67.3) | 279 (60.3) | 0.032 | ||

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 215 (28.1) | 163(35.2) | |||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 35 (4.6) | 21 (4.5) | |||

| Complications | |||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 148 (21.3) | 129 (30.1) | <0.001 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 18 (3.7) | 18 (5.8) | 0.160 | ||

| Heart failure | 51 (10.3) | 44 (13.8) | 0.137 | ||

| Angina | 42 (8.6) | 32 (10.4) | 0.389 | ||

| Hypertension | 569 (75.1) | 342 (76.3) | 0.619 | ||

| Diabetes | 209 (27.8) | 109 (24.2) | 0.179 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 275 (37.3) | 124 (28.2) | <0.001 | ||

| Respiratory disorders | 28 (5.8) | 27 (8.8) | 0.107 | ||

| Cancer | 38 (10.0) | 29 (12.8) | 0.272 | ||

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 80 (13.3) | 39 (12.2) | 0.628 | ||

| Constipation | 287 (39.2) | 193 (45.5) | 0.036 | ||

| Hospital stay | 110.0 ± 53.1 | 144.6 ± 62.3 | <0.001 | ||

| Acute phase | 27.0 ± 14.9 | 33.2 ± 16.5 | <0.001 | ||

| Convalescent phase | 83.0 ± 49.2 | 111.4 ± 59.2 | <0.001 | ||

| NIHSS at admission to an acute ward | 8.3 ± 6.9 | 12.3 ± 8.0 | <0.001 | ||

| mRS at admission to an acute ward | |||||

| 0–2 points | 46 (9.5) | 16 (5.3) | 0.033 | ||

| 3–6 points | 439 (90.5) | 287 (94.7) | |||

| mRS at acute ward discharge | |||||

| 0–2 points | 108 (22.8) | 14 (4.7) | <0.001 | ||

| 3–6 points | 365 (77.2) | 286 (95.3) | |||

| mRS at convalescent rehabilitation ward discharge | |||||

| 0–2 points | 380 (60.5) | 33 (8.8) | <0.001 | ||

| 3–6 points | 248 (39.5) | 341 (91.2) | |||

| Caregivers at home | |||||

| No | 277 (47.0) | 172 (52.9) | 0.084 | ||

| Yes | 313 (53.1) | 153 (47.1) | |||

| Day/night | 184 (58.8) | 51 (33.3) | |||

| Daytime only | 21 (6.7) | 19 (12.4) | |||

| Nighttime only | 108 (34.5) | 83 (54.2) | |||

| Urination status | The location of voiding before the stroke | ||||

| Toilet or bedside commode | 682 (93.2) | 378 (86.1) | <0.001 | ||

| On the bed (diaper or indwelling catheter) | 50 (6.8) | 61 (13.9) | |||

| The location of voiding at acute ward discharge | |||||

| Toilet or bedside commode | 454 (64.2) | 78 (17.8) | <0.001 | ||

| On the bed (diaper or indwelling catheter) | 253 (35.8) | 360 (82.2) | |||

| The location of voiding at convalescent rehabilitation ward discharge | |||||

| Toilet or bedside commode | 634 (86.4) | 159 (35.0) | <0.001 | ||

| On the bed (diaper or indwelling catheter) | 100 (13.6) | 295 (65.0) | |||

| ADL (motor and cognitive functions) | FIM at acute ward discharge | ||||

| Total FIM cognitive items | 24.4 ± 8.3 | 14.0 ± 7.7 | <0.001 | ||

| Bladder control | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Bowel control | 5.1 ± 2.3 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | <0.001 | ||

| Toileting | 4.4 ± 2.2 | 2.0 ± 1.6 | <0.001 | ||

| Toilet transfer | 4.7 ± 2.0 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | <0.001 | ||

| Walking | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 1.8 ± 1.4 | <0.001 | ||

| FIM at convalescent rehabilitation ward discharge | |||||

| Total FIM cognitive items | 27.7 ± 6.8 | 16.9 ± 8.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Bladder control | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Bowel control | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 3.1 ± 2.3 | <0.001 | ||

| Toileting | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Toilet transfer | 6.1 ± 1.4 | 3.4 ± 2.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Walking | 5.7 ± 1.8 | 2.9 ± 2.1 | <0.001 | ||

Data are given as means ± SD, or n (%).

Statistical analysis was by Student's t-test or Pearson's chi-square test.

Binomial logistic regression analysis revealed that age (AOR: 2.801, 95% CI [1.473, 2.940]; P <0.001), sex (AOR: 1.513, 95% CI [1.112, 2.059]; P=0.008), stroke type (AOR: 1.426, 95% CI [1.013, 2.007]; P=0.042), total FIM cognitive item score (AOR: 3.750, 95% CI [2.615, 5.379]; P <0.001), bladder control (AOR: 2.056, 95% CI [1.223, 3.454]; P=0.007), and bowel control (AOR: 2.823, 95% CI [1.688, 4.722]; P <0.001) were associated with discharge to home from a convalescent rehabilitation ward (Table 2).

| AOR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 2.081 | 1.473 – 2.940 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 1.513 | 1.112 – 2.059 | 0.008 |

| Stroke type | 1.426 | 1.013 – 2.007 | 0.042 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.198 | 0.842 – 1.706 | 0.316 |

| Total FIM cognitive items | 3.750 | 2.615 – 5.379 | <0.001 |

| Bladder control | 2.056 | 1.223 – 3.454 | 0.007 |

| Bowel control | 2.823 | 1.688 – 4.722 | <0.001 |

Binomial logistic regression analysis:

Age (65 to <75 years:1, >75 years: 0). Sex (Male: 1, Female: 0).

Stroke type (cerebral infarction・subarachnoid hemorrhage: 1, cerebral hemorrhage: 0).

Atrial fibrillation (No: 1, Yes: 0).

Total Functional Independence Measure (FIM) cognitive items (≥25 points: 1, <25 points: 0).

Bladder control, bowel control (≥5 points: 1, <5 points: 0).

Tests for the whole model: P <0.001. Contribution rate: 0.305. Lack of fit: P=0.028.

This study examined the factors associated with home discharge from a convalescent rehabilitation ward using the KRCCPS database and revealed that the home discharge rate was 62.3%. Home discharge was associated with age, sex, stroke type, cognitive function, and ADL items related to bladder and bowel control.

The home discharge rate in this study was consistent with the results of a nationwide survey in Japan.5,30) Furthermore, the average age and the sex ratio in this study were the same as those in the nationwide survey; however, the rate of cerebral hemorrhage was approximately 10% higher in this study. Therefore, the current study appears to reflect the general situation of stroke patients in Japan.

The FIM bladder control score was associated with home discharge during the convalescent phase and was in line with that of a previous study,17) which reported that the FIM toileting score predicted home discharge in the acute phase with 67% accuracy. Both studies showed the importance of improving urinary continence for home discharge of stroke patients. Patients require assistance when voiding behavior is impaired, resulting in an increased burden for caregivers that is greater than the burden for assistance with other ADLs, such as eating and dressing. Generally, individuals urinate several times a day, and patients will likely require assistance at night. The frequency of urination sometimes reaches 15 times/day in older adults. Urination also includes many complex behaviors, including getting out of bed, moving to the toilet, lowering underwear on the toilet, maintaining posture during voiding, and cleaning the urogenital area using toilet paper. This often requires a large amount of assistance. Moreover, many caregivers experience physical and psychological challenges because of the odor and soiling associated with urination, cleanup of unsuccessful attempts, and response to the patient’s discomfort due to a sense of urgency.31,32) Therefore, a lower level of bladder control, including requiring partial assistance for urination, likely contributes to the inability to achieve discharge to home.

There is a difference between the subscales of FIM related to home discharge used in a previous study17) and those used in the present study. The FIM bladder control score, a factor related to home discharge in the present study, represents physical and cognitive functions to void in appropriate situations and to prevent urinary leakage, whereas the FIM toileting score used in the previous study implies independence of voiding behavior. Considering this difference, the present study showed the importance of controlling lower urinary tract symptoms, even after patients improve ADL scores for voiding behavior in the convalescent phase. Patients with frequent urination need to go to the toilet repeatedly, and patients with urinary leakage need to change their pads whenever they urinate. Caregivers have a higher burden of assistance for voiding behavior when patients have lower urinary tract symptoms. To achieve home discharge, it is important to reduce the amount of assistance required by improving ADL and control of lower urinary tract symptoms. We attempted to assess the type of lower urinary tract symptoms based on the records of care provided by pharmacists and nurses; however, we decided against this approach because the KRCCPS database does not include the diagnosis of lower urinary tract symptoms. The absence of such data may imply that knowledge and assessment skills regarding lower urinary tract symptoms are not widespread among healthcare professionals involved in treating stroke and that priority for the treatment of lower urinary tract disorders is low. Based on this study, it will be necessary in the future to provide continence care to promote independent urination based on the assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms in stroke care.

Similarly, low independence in ADL for bowel control also inhibited discharge to home. The proportion of those with chronic constipation, particularly evacuation difficulty, is high among bedridden older adults.33) For evacuation difficulty, which is known as the presence of a hard fecal mass obstructing the rectal vault, home visiting nurses provide digital disimpaction and enemas and control the need for defecation care from family members. The relationship between lower bowel control and home discharge has not yet been investigated. Considering that the inability to defecate independently inhibits home discharge and that constipation itself can cause lower urinary tract symptoms,34) management of both defecation and urination is important regarding treatment courses, improving ADL, and adjusting the toilet environment.

Age, sex, and stroke type affected home discharge from the convalescent phase. It is reportedly more difficult for older individuals10,11) and women9) to be discharged to home after the acute and convalescent phases, and our results were consistent with those of previous studies. Older stroke patients are affected by age-related functional decline in addition to disease-specific disorders, making it difficult for them to recover their pre-onset levels of ADL. One of the possible reasons for the relationship between home discharge and sex is that women tend to assume the roles of housekeeping and caregiving in Japan, and the change in their roles after stroke onset may make it difficult for them to be discharged home. However, there was no difference in the proportion of men and women having caregivers at home. Although husbands are regarded as caregivers, they might not be able to provide the care their wives need to stay at home because they are usually older than their wives.

A nationwide survey30) suggested that cerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage more severely affect physical status at onset than does cerebral infarction and were more likely to result in longer hospital stays or institutional outcomes. This result was similar to the current finding that cerebral hemorrhage was related to the inability to achieve home discharge.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not investigate some potential variables related to home discharge, including family composition, the care capabilities of family members, causes of lower urinary tract dysfunctions, and methods of voiding management, such as clean intermittent catheterization. In the future, based on the results of this study, items on voiding and storage dysfunction and voiding management methods need to be added to the database and investigated. Second, the worst conditions of ADL and urination location were used in this study. These variables might not reflect the true status of patients because patients with low ADL often use the toilet during the daytime but use a bedside commode at night. It might be better to use the best condition or most common condition throughout the day in future research.

In conclusion, this study examined the factors associated with home discharge from the convalescent rehabilitation ward using a database that was shared by acute wards and convalescent rehabilitation wards. In addition to age, sex, stroke type, and cognitive function, the ADL scores related to bladder and bowel control were factors affecting home discharge. Improved continence management for both voiding and defecation could therefore be a promising care strategy to promote hospital discharge to home in stroke patients.

We thank all the study participants for their cooperation and the Council of Kaga Local Stroke Network, South Ishikawa, Japan, for their support. This study was supported by research grant 20-03-184 from the Univers Foundation in 2020–2021.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.