2015 年 43 巻 SUPPLEMENT 号 p. 57-60

2015 年 43 巻 SUPPLEMENT 号 p. 57-60

The parasite, Onchocerca volvulus, was first detected in a Ghanaian by a German missionary in 1890 and was nominated Filaria volvulus by Leuckart (1893). No pathogenicity of the parasite was found yet. In 1915, however, R. Robles reported the new distribution of this filarial parasite in Guatemala, Central America, after enormous parasitological, clinical and epidemiological studies of coastal erysipela (Erisipela de la costa). He clarified that O. volvulus caused ocular lesion and the denodulization improved the symptoms remarkably. This is the reason that the Government of Guatemala launched denodulization campaign in the endemic areas since 1935. Based on the specimens obtained by Robles and other information on vector blackfly species, Brumpt (1919) proposed O. caecutiens n.sp., while this new species was neglected by various parasitologists. Identification of vector insect blackfly by Blacklock in 1926 clarified transmission mechanism and encouraged vector control trials in Africa (Garnham and McMahon, 1947) in particular the Onchocerciasis Control Program (OCP) in late 1960s.

A filaricide drug Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) showed curative effect, while it caused severe accessory reactions in the infected people as seen in Mazzotti reaction. Thus the mass treatment has been considered difficult before the appearance and registration of Ivermectin (Mectizan). Mass treatment by lvermectin based on the community based system recently accelerated African Program for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) in Africa and Onchocerciasis Eradication Program of America (OEPA) in Central and South Americas in 1990s.

Epidemiological viewIn 34 countries in the world, 17.7 million people (17.5 millions in Africa, 30 thousands in Arabia Peninsula and 140 thousands in America) are estimated to be infected and 270 thousands are blind (Table 1). The estimated global damages by onchocerciasis are 880,000 DALYs. The infections in Volta River basin covered by OCP since 1974 were greatly reduced from one million people to only 10 thousands in 1992. No more transmission occurred among children in the OCP area [1].

| Region | Population at risk of infection (millions) | Population infected | Number blind as a result of onchocerciasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||

| OCP area: | |||

| Original area | 17.6a | 10,032 | 17,650 |

| Extensions | 6.0 | 2,230,000 | 31,700 |

| Non-OCP area | 94.5 | 15,246,800 | 217,850 |

| African subtotal | 118.1 | 17,486,832 | 267,200 |

| Arabian peninsula | 0.1 | 30,000 | 0 |

| Americas | 4.7 | 140,455 | 750 |

| Total | 122.9 | 17,657,287 | 267,950 |

a The population given is that which would have been at risk had the OCP not existed (WHO, 1995).

As is called “River blindness”, the ocular lesions particularly the damage and loss in visual acuity are the characteristic features of this disease. Onchocercal dermatitis and subcutaneous nodules are the other important lesions. The skin disease (pruritus, papules, excoriations, depigmentation, pachydermia etc.) which accompanies strong itching shares half the global DALYs of onchocerciasis and needs treatments of adult parasites because of its socioeconomic importance. On this context macrofilaricides such as Amocarzine, UMF 078 and etc. are now under clinical trials. The nodules called onchocercomatas show characteristic distribution patterns in each continent: No nodules are found on the head in Africa, while half the nodules are on the head in Central America.

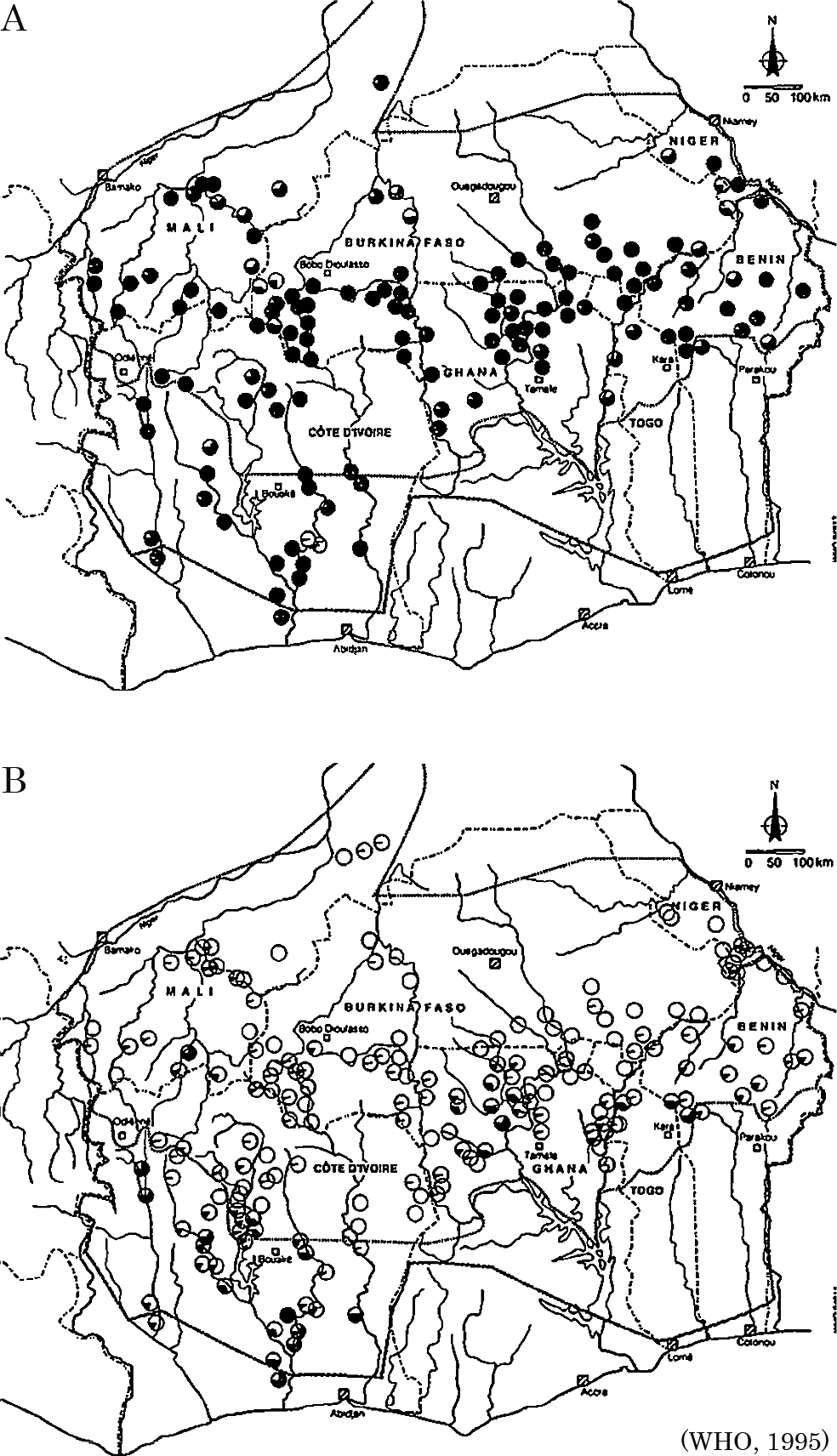

Control programsOCP adopted vector control operations by spraying larvicides such as Temephos (Abate) in the breeding rivers for Simulium damnosoum complex in the beginning and then added Ivermectin delivery system. Basically 12 thousand km of river were under weekly spraying of larvicide during rainy season. Rotation of larvicides and biological larvicide (B. thrungiensis H-14) were also adopted later. OCP prevented 9 million children born within original OCP area from the risk of onchocercal blindness. Thirty million people are protected from infection and 100 thousands have been prevented from going blind (Fig. 1A, B). Thus OCP opened up the way for resettlement in fertile areas along the rivers, previously deserted through fear of disease. OCP activity was scheduled to cease in the year 2002. During the successful achievement of OCP, OEPA (started in 1993) and APOC (started in 1996) were planned and launched in other endemic areas of the world. Both programs rely on the community directed treatment system based on the Ivermectin and supported by Geographic Information System (GIS) for rapid epidemiological mapping.

A Pre-control prevalence of skin microfilariae in villages in the original OCP area. B Prevalence of skin microfilariae in villages in the original OCP area: 1992–1993.

No research has ever been performed by Japanese before a joint study of skin test by us [2]. In 1970, I visited a plantation Panajabal, located in Sierra Madre Mountains of Guatemala, guided by Dr. H. Figueroa for the first time. The plantation was one of the most highly endemic areas of the disease in America. A blind old man has been walking there. The miserable scene shocked me greatly. Fortunately I was awarded with an opportunity to learn more about onchocerciasis in Ethiopia being dispatched by the ODA agency, OTCA (Overseas Technical Cooperation Agency, Japan), next year together with 2 Japanese entomologists and one parasitologist. We visited several times the endemic areas and obtained technical experiences and epidemiological data there. In 1973, I was sent to Guatemala for further investigation on onchocerciasis by OTCA. I proposed a report of a brief epidemiological survey to the Governments of Guatemala and Japan asking the survey and control of this disease. Mr. J. Mori, the Ambassador of Japan, requested Japanese government to start a research project for the control of onchocerciasis through JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) (Table 2).

| Research timeline of human onchocerciasis in Japan | |

|---|---|

| 1969 | Result of skin test study on onchocerciasis in Guatemala was reported (I. Tada and H. Figueroa) |

| 1970 | I. Tada visited an endemic plantation in Guatemala C.A. to see onchocerciasis |

| 1971 | Four Japanese stayed in Ethiopia dispatched by Overseas Technical Cooperation Agency (OTCA) for the technical collaboration and study of onchocerciasis (Team leader: T. Ohse) |

| 1973 | I. Tada: Brief survey of onchocerciasis in Guatemalan endemic areas dispatched by OTCA. J. Mori requested Japanese Government to support research and control as the Ambassador of Japan |

| 1975 | JICA: Dispatch of Basic investigation team to Guatemala (Headed by A. Nakajima) |

| JICA: Dispatch of Project installation team to Guatemala (Headed by S. Hayashi) to exchange Record of Discussion (RD) | |

| 1976 | JICA-Technical cooperation project of onchocerciasis started (Team leader: H. Takahashi, Chief of JICA Steering Committee: S. Hayashi) |

| 1980 | JICA: Three-year extension of research project (Team leader: T. Suzuki) |

| 1981 | JICA-Guatemala: International Congress of Onchocerciasis (Guatemala City) |

| 1982 | Min. Education, SC, Japan supported a comparative study of onchocerciasis and its transmission between South and Central Americas (1) (Headed by I. Tada) |

| 1983 | JICA: Collaboration project expired. Among the Japanese experts, Y. Yamagata later joined OCP |

| 1984 | Min. Education, SC, Japan: a comparative study of onchocerciasis and its transmission between South and Central Americas (2) |

| 1985 | JICA: Jos University (Nigeria) project dealt with onchocerciasis (Team leader: H. Takahashi) |

| 1986 | I. Tada joined WHO Expert Committee on Onchocerciasis (Geneva) Min. Education, SC, Japan: a comparative study of onchocerciasis and its transmission between South and Central Americas (3) |

| 1987 | Publishment of 3 volumes of Green books (ed. by I. Tada) dealing with studies supported by Min. Education, SC, Japan |

| 1990s | H. Takaoka: Human infections with zoonotic Onchocerca infections in Japan |

| 1997 | I. Tada: Participation to Task Force meetings by TDR/WHO for global onchocerciasis control |

Thus a technical collaboration project started in 1975 (Actually it started in early 1976 because of a big earthquake) and lasted successfully for 8 fiscal years. The majority of the field works were performed in San Vicente Pacaya County. The project yielded various products in terms of technologies in entomological, parasitological, ophthalmologic, and epidemiological fields [3]. In this project a total of 90 Japanese experts were dispatched and 13 Guatemalan counterparts were awarded with fellowship to visit and learn in Japan. Apart from the scientifically new findings related to onchocerciasis, standardization of various techniques such as immunodiagnosis, inseticide spraying, identification of vector blackflies etc. was intensively promoted. Eventually about 90 scientific papers and a set of technical manuals were produced. Further an international congress of onchocerciasis was convened in 1981 under the auspices of Guatemalan government and JICA with the participation of experts of onchocerciasis control from WHO/OCP [4].

2) Research project on the origin of Central American onchocerciasisDuring this ODA project, a question has arisen whether the onchocerciasis in Guatemala was imported by slave trade from West Africa or was autochtonous in continental America [5]. This has been a matter of arguments in Guatemala and Mexico since when Brumpt proposed O. caecutiens as new species. Perforation of the skulls of Pre-Colombian inhabitants suggested its onchocercal origin and Duke and colleagues suggested biological remoteness of O. volvulus between South American and African parasite strains. In order to examine this question, my colleagues and I launched a research project to investigate the origin of onchocerciasis in Central America being supported by the grant from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan during the period between 1982 and 1987.

A total of 12 parasitologists and medical entomologists joined this project. We compared O. volvulus and its transmission in Guatemala, Ecuador, Venezuela and Nigeria using cytogenetic, parasitological, entomological, histochemical and morpho-metrical methodologies. For the comparison of O. volvulus from Central America (Guatemala) and South America (Venezuela), we adopted the methodologies of Duke et al. [6] and compared biological similarity of each strain to vector blackfly by the cross infection. Cytogenetic analysis of the parasite from Central/South America and Africa revealed a decisive conclusion on the identity of the parasite [7]. Finally we concluded that Guatemalan Onchocerca was biologically quite similar to that of South America and thus considered that it had been imported from Africa by the slave trade, too [8].

3) AftermathIn 1997, I was invited to two Task Force meetings of TDR (Filariasis) and in that occasion I could visit a former endemic village at Burkina Faso, West Africa. Although no more transmission has been occurring in this area due to the long lasting and successful control operations by OCP, I saw a blind old man walking around with stick by himself among actively playing children. Apparently the villagers have come back to once abandoned site as the blackflies completely disappeared. The scene overlapped his counterpart in Guatemala with whom I met 27 years ago. OCP was certainly a successful health program against riverblindness and hence APOC/OEPA also should reveal similar good results.

On the other hand, I would like to indicate a serious fact: After a rush of research on Onchocerca and its transmission, very few Japanese scientists or, I might say, only one, are engaging in the study of Onchocerca nowadays. Even though we have established the tool and way of control/elimination of onchocerciasis, is research of Onchocerca not necessary anymore? German scholars belonging to Bernhard-Nocht Institute of Tropical Medicine are still continuously reporting their research activities based on field laboratory in Liberia. They range from morphological to molecular biological findings which are very important to understand parasitism and its treatment in general. On this context, I feel strong necessity to establish and maintain an institution in tropical countries collaborating with local staff. Because Japan lacks adequate number of qualified scientists in infectious and parasitic diseases and tropical medicine.

In the era of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, field research is very important to promote research of infections and parasitic diseases.

Reproduced from Japanese Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Vol. 27, 33–37, 1999, with kind permission from Japanese Society of Tropical Medicine