2019 年 2 巻 p. 1-14

2019 年 2 巻 p. 1-14

This paper analyzes the core essences of social media in Vietnam in the era of Facebook prominence, from 2013 to the establishment of the Cyber Security Law in June 2018. With the growth of social media, unprecedented opposition forces have emerged on social media and challenged the political structures of the single-party country. This paper juxtaposes social media and journalism in Vietnamese political and cultural contexts. First, it indicates a sharp contrast between social media and journalism in six perspectives: function, content, the concept of freedom, content generators, legal framework, and cost. Second, it discusses the differences between traditional Vietnamese social power structures and social media, focusing on the characteristics of religions in Vietnam, the Power Distance Index, and the theories of high and low-context communication. The paper concludes that the essences of social media undermine the existent structures of journalism and social power by creating a space for public criticism and activism to challenge the government. Many opposition groups have been formed and institutionalized on social media, resulting in pluralism in Vietnamese politics and society. The analysis of Tôi và sứ quán (Embassies and Me) Facebook Page provides examples to clarify the differences between social media, and journalism and social power structures in Vietnam, as well as the institutionalization of the opposition groups on Facebook.

Vietnam is a single-party state in Southeast Asia. The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) has been the founding political party since the national declaration of independence in 1945 and the ruling political party since the country’s union at the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 (BBC, 2017). The country has a very young population; the 10-24 age group accounts for 40% of the 96 million in total (Long, 2016; Worldometer, 2018). Vietnam’s annual economic growth rate has steadily increased from 5.7% to 7.5% between 2008 and 2018, maintaining its position as a regional out-performer and the second fastest growing global market, after China (Minh, 2014).

To serve the dynamic young population and robust economic growth, the country has developed its connection to the global information network. Internet was first introduced to Vietnam in 1997. By the end of 2000, there were just over 200,000 Internet users in the country. As of January 2018, the number of Vietnamese Internet users tremendously expanded to over 55 million (Statistic, 2018b). International Telecommunication Union listed Vietnam among the fastest growing telecommunication industries worldwide, with significant qualitative and quantitative enhancements in mobile networks, broadband Internet, and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) devices (OMIS, 2011). A 2015 report by Gallup and BBG indicates the dominance of mobile Internet in the Vietnamese telecommunication industry; 80.5% of the users reported to access the Internet via their mobile phones. The report also remarked that Vietnam has a huge market for cheap mobile phone ownership. According to Internet SpeedTest (speedtest.net), in August 2018, the fixed broadband Internet speed of Vietnam reached 25.61 megabits per second (Mbps) for downloading and 25.35 Mbps for uploading, ranking 57th globally. The mobile Internet speed ranked 70th globally, with 19.69 Mbps for download and 10.28 Mbps for upload speed.

Such accelerated access to the Internet is a major component of an expanding mix of media, and social media is the latest segment in this mix. As of January 2018, Vietnam ranked the seventh in the world in terms of the number of Facebook users, after India, United States, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, and the Philippines (Statistic, 2018a). On average, each Vietnamese user spends 2.5 hours per day on Facebook, twice as longer than the time spent watching TV (M. T., 2015). A research by Pew (2018, p. 32) indicates that 81% of the Vietnamese between the ages of 18 and 29 get their daily news from social media. Vietnamese social media users tend to be younger, more educated, and wealthier than the general population (Pew, 2018, p. 38). As social media use becomes an increasingly widespread phenomenon in Vietnam, this paper aims to review the development of social media, its distinct characteristics and nexus to other media in the Vietnamese context. It compares social media to journalism, and social media culture to Vietnamese culture. T Facebook Page Tôi và sứ quán1 (Embassies and Me) is used as a case study to provide examples of the distinct characteristics of social media.

The Government of Vietnam, states that “Online social media is a service providing a broad community of users the possibility to interact, share, store and exchange information among each another on the Internet environment, including blogs, forums, chats, and other similar forms” (Item 14, Article 3, Decree No. 97/2008/ND-CP, issued by the Vietnamese National Assembly in 2008). According to this Decree, a website is considered as a social media website if (1) people can interact on the website by sharing and leaving comments, and (2) the website content is generated by users. Echoing this definition, Bradley (2010) claims that “Social media is a set of technologies and channels targeted at forming and enabling a potentially massive community of participants to collaborate productively.” In Bradley’s definition, social media technologies were listed in detail as “social networking, wikis, and blogs enable collaboration on a much grander scale and support tapping into the power of the collective in ways previously unachievable.”

Social media in Vietnam started with the introduction of Yahoo! 360°, launched in several countries in June 2005. At the dawn of social media, Yahoo! 360° was the self-publishing platform for the so-called “chick-lit” in Vietnam where well-known young women writers shared their short stories, translated novels, and diaries. The public used Yahoo! 360° to connect to their favorite writers, and share their writings and photos (Pham, 2013). The Yahoo! 360° wave was so strong that it was nominated among the top ten ICT developments in Vietnam in 2006 by the VietnamNet media organization. Between 2006 and 2009, well-known journalists started to blog about entertainment, politics, or the journalism practice itself, and earned a reputation for their blogs. Some notable examples are journalist Truong Huy San’s blog Osin, Le Nguyen Huong Tra’s Cô Gái Đồ Long, and Truong Duy Nhat’s Một góc nhìn khác (Trang, 2013). In July 2009, Yahoo! 360° was shut down after some poor technical maintenance. Vietnamese bloggers scattered to many other social networks such as Yahoo Plus, Opera, Multiply, WordPress, Zing, Facebook, and Blogspot (Quinn & Kierans, 2010, p. 2).

Before the prime time of Facebook and YouTube, Vietnam observed substantial online communities gathering on popular forums such as ttvnol, vn-zoom, and webtretho that acquired half a million, six million, and 1.6 million member accounts, respectively, in early 2015 (Do & Dinh, 2014, p. 4). In a media seminar in January 2015, Mr. Truong Minh Tuan,2 the former leader of the Ministry of Information and Communication of Vietnam, said that Vietnam recorded an impressive increase from 130 social networks in 2011 to 420 in 2015, and anticipated continuous growth as well as the absolute integration of social networks in society.

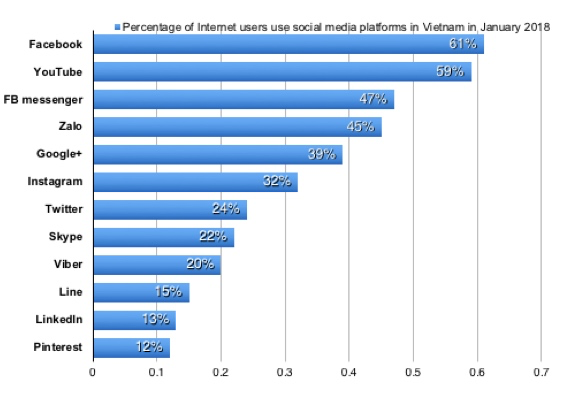

Figure 1 indicates the most popular social network and chat applications in Vietnam in January 2018. Facebook and YouTube are at the top of the list, attracting 56% and 59% of the surveyed population, respectively. Next in line are Zalo, Google+, Instagram, Twitter, Skype, Viber, Line, LinkedIn, and Pinterest. In this list, only Zalo is owned and developed by a Vietnamese company, VNG. The others are international-based platforms. According to these statistics, 61% of Internet users use Facebook and 47% use Facebook Messenger; overall, Facebook is the top social network in Vietnam.

Figure 1. Most active social media platforms in Vietnam, January 2018 (Source: We-are-social and Hootsuite)

The Vietnamese government controls social media by technological tactics and legal frameworks. Although there is evidence of Facebook blockage in 2009 and some other short term blockages of Facebook after 2009 (GALLUP, 2015), the government has continually promised that there would be no technical interference to block or ban social media in Vietnam (BBC, 2015; Cao, 2017). The Vietnamese government has neither officially forbidden social media nor issued any legal documentation regulating technical barriers for social media. However, it has been observed that during some big national events, technical problems often occur in digital communication, including social media. For example, it was impossible to send text messages (SMS) containing keywords cá chết (dead fish) and Formosa during the outbreak of the sea disaster caused by the Hung Nghiep Formosa Co. Ltd. in April 2016. Also, Facebook was blocked during the week of US President Barack Obama’s visit to Vietnam in late May 2016.3 The same problem occurred with messages containing CPV leaders’ names during the Vietnamese National Assembly and the three levels of administration elections in May 2016. The undersea cable providing Internet to Vietnam is often physically destroyed4 during national meetings of the CPV or the National Assembly, or during important courts accusing top national leaders. This is in line with Verhulst’s claim (2002) that there has been a shift from content control to technological infrastructure control in digital communication regulations.

Decree No. 72, issued by the Vietnamese government in 2013, is frequently cited to regulate social media in Vietnam. According to the Article 26 of Decree No. 72, users are responsible for the content of their information storage, supply, transmission on social network, and for distributing information via direct links that the users set up. Since 2009, anti-government content on social media has been banned and controlled under Articles 79, 88, and 258 of the Penal Code, which respectively ban taking advantage of freedom of speech to violate state interests; anti-state propaganda; and actions aimed at overthrowing the government. In the Amendment to the Penal Code, enacted in January 2018, the orders of such articles have been changed to 109, 117, and 331. The new items added to these amended articles convict not only criminals but also those who are about to perform the illegal actions. With these new items, the Amendment to the Penal Code is believed to be much stricter than the previous.

Notably, the Cyber Security Law has been enacted since June 2018. This law adds critical constraints to the expression of dissidence on the Internet and social media. The distinguishing feature of the Cyber Security Law (Government, 2018) is the localization of data. It requires all data relating to Vietnamese social media users to be physically kept on Vietnamese territory, which enables Vietnamese authorities (policemen) to easily access the data (Article 26). As a consequence, international social networks such as Facebook and Google are required to host the data in Vietnam. Another remarkable feature of the Cyber Security Law is that it allows for the removal of information that the authorities consider to be “wrongful” (Article 26b) or “causing social disorder” (Article 5.1.i). Individuals and organizations violating the law are restricted or banned from accessing online platforms (Article 5.1.l). Analysis of the official enactment of the Cyber Security Law since January 2019 reveals its adverse impact on the use of social media to criticize the authorities. Four aspects are adversely impacted: privacy, freedom of expression, the right to use telecommunication services, and the right to benefit from ICT and social networks (Savenet, 2019, pp. 77-78).

Many scholars (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Press & Williams, 2010; Moens, Li, & Chua, 2014) agreed that user-generated content (UGC) is the attribute that distinguishes social media from other media. UGC has three basic requirements: (1) to be published on accessible websites or social networking sites; (2) to show a certain amount of creative effort; and (3) to be created outside of professional routines and practices (Moens, Li, & Chua, 2014, p. 8). In cyberspace, businesses and authorities have less control over the information about them, since people can say what they want and bypass censorship (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010, p. 60). UGC tends to be collaborative and encourages sharing and joint production of information, ideas, opinions, and knowledge; and serves as an alternative source of information that challenges the gatekeeping functions of other media (Press & Williams, 2010, p. 20; Moens, Li, & Chua, 2014, p. 17). Moens, Li & Chua strongly asserted that UGC can also be seen as an open platform that enriches political and societal debates and diversity of opinion, and creates the free flow of information and freedom of expression (2014, p. 17).

Non-hierarchical culture.Social media increasingly undermines hierarchical management (Pérez-Latre, 2013, p. 47). Such advance in technology enables people to actively get the information they need from other people, instead of relying on institutions such as governments or companies. Young and educated people said that they had built a growing trust in the information they get from social media (GALLUP, 2015). Personal relationships have also been profoundly changed by social media; superiors and inferiors are now friends (Pérez-Latre, 2013, p. 47). Jones (1998, p. 25) explained that such retribalization occurred because of the absence of the rich context of face-to-face communication. On the Internet, people are often faceless, transient, or anonymous; forms of real-life communication is lacking online and our interactions are mechanized and hollow. The anonymity of the medium has a powerful, disinhibiting effect on behavior. Social media can challenge even the most authoritarian regimes, given its ability to break hierarchy. For example, in Vietnam, some anonymous blogs5 displayed evidence of corruption executed by highly positioned politicians, which could ruin the proclaimed legitimacy of the Party in Vietnam. The CPV considers these blogs as “the reactionary arms” (VietnamNet, 2015).

Low-context communication.Like other forms of Internet communication, social media is mainly text-based. People cannot see each other and the settings around them. Social media is included in the low-context environment of communication (Jones, 1998, p. 131). Since it is text and technology-based, the success of conversations on social media is mostly dependent on its users’ literacy and skills to adopt the digital technology (Hartley, 2002, p. 58), which could well clarify why the majority of well-known social media users are elites, intellectuals, journalists, businessmen, and urban youth, who can afford the favorable conditions of education and Internet penetration.

Journalism in Vietnam is based on a Marxist-Leninist prototype developed in the erstwhile Soviet Union, as the Communist Party claims Leninism and Marxism as the foundation of the Party’s doctrine. Journalism was defined as the “device for social control, managed exclusively by the State and Party” (Pike, 1970, p. 4). Its purpose is to “support the legitimacy of the Communist Party and its rightful hold on society” (Cain, 2014, p. 90). It is noted that “the mission of press is to serve the people by serving the government” (Shafer, 2006, p. 21), and consequently, media organizations defined themselves as mouthpieces of governmental organizations with which they are affiliated. Huu Tho, a well-known Vietnamese journalism trainer, states in his textbook, Công việc của người viết báo (The Jobs of Journalists), “Since journalists are the spokespeople for the Party, the first and foremost truth is the Party’s truth” (1997, p. 25). This “Party-first” policy tightens censorship until self-censorship becomes second nature for journalists, and specific topics that could be considered as harmful to the power of the Party will be blacked-out on mainstream media (Marr, 1998, p. 3).

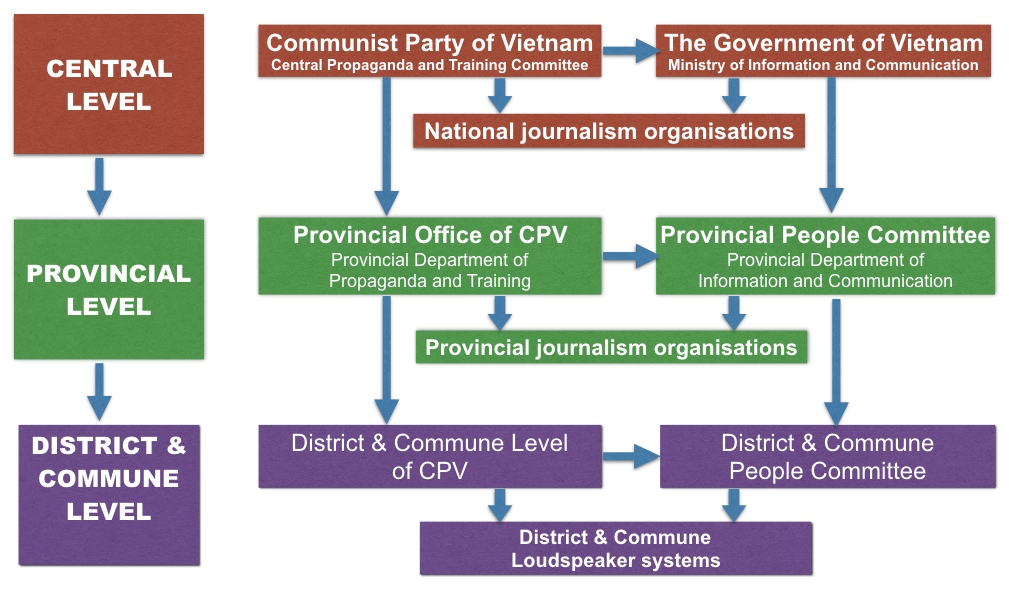

Structure.Vietnamese journalism is strongly affiliated with governmental organizations. Figure 2 illustrates the management structure of Vietnamese journalism. It is adapted from the teaching materials of the Academy of Journalism and Communication, Vietnam. The arrows in this diagram indicate the flow of guidance and commands from the higher to the lower organizations in the management structure, and from the Party’s blocks to the State’s blocks.6

Figure 2. The management structure of Vietnamese journalism.

According to Article 14 of the Vietnamese Press Code issued in 2016, the right of journalism ownership belongs to “Party’s organizations, governmental organizations, political organizations, socio-politic organizations, professional organizations, and other governmental organizations recognized by the government.” The press codes over the years have constantly rejected private sector’s involvement in journalism. Performance of all mass media organizations is under the direct control of the Central Propaganda and Training Commission (CPTC) under the CPV and Ministry of Information and Communication (MIC) under the Government at three levels: center, province (or city), and district and commune.

National management of Vietnam is divided into three administrative levels: the central, the provincial, the district and commune (Funston, 2001, p. 381). At the central level, CPTC (a unit of the CPV) and MIC (a unit of the Government) manage all perspectives of the nation’s media. Some central-level mass media organizations could be named, such as Nhan Dan7 (the People) newspaper, Vietnam News Agency,8 Vietnam Television,9 The Voice of Vietnam,10 and the system of newspapers and magazines run by the ministries. The provincial level is under the central level. Each province has at least three media houses: a newspaper, a broadcasting station, and an online portal. Besides, national associations can run newspapers at this level and assign to their provincial offices the management of such media houses. The lowest level is the district and commune. Each district unit runs its own television station, which delivers information from the local government to the local people. It also produces local programs to contribute to the upper-level journalism organizations. Although in alignment with the guidance from the Party and Government, their purpose is information delivery rather than journalism, because they target a small district or commune audience; the information is one way, top-down from the authority to the people; and the staffs are not required to obtain press cards.

Although Vuving (2010, p. 376) recognizes that journalism has gained significant autonomy vis-à-vis the Government (particularly the semi-financial autonomy with the profits from advertising), media practices are still under apparent control. For instance, all media practitioners must be affiliated with media organizations and meet requirements to obtain press-cards issued by the MIC. The Government appoints senior leaders for media houses, who attend the weekly meetings with representatives from the Party’s CPTC for agenda setting, to ensure their cooperation with the Party (Press Law issued in 2003).

Content about positivity.Vietnamese journalism promotes content about “the good.” Huu Tho asserts: “To transition to socialism, journalism should emphasize good people, good deeds, and advanced cases to encourage the revolutionary” (1997, p. 117). He justifies two reasons why reflecting the good should be a distinct characteristic of journalism in socialism. First, journalists’ work should continuously confirm that the essence of socialism is good. Second, the proletariat can see the benefits they could obtain when they learn from good examples, which helps to achieve the Party’s goal in business development (Tho, 1997, pp. 115-117). As a result, success, achievement, encouragement, and agreement are elements for sound coverage to boost development in Vietnam.

To serve the Communist Party’s anti-corruption cause after Doi Moi, the economic reform launched in 1986, newspapers have been given “the licence to report about corruption” (Macan-Markar, 2003). Thus, publishing negative aspects of government officials has been an acceptable practice. However, police officers play the role of information filters, and pre-censor. When the room for controversy and negativity increases, it possibly leads to dissent that journalism within strict Party’s restriction could not fully reports (Wells-Dang, 2012, pp. 4-5). Journalism maintains its primary duty as being the mouthpiece for the Party and State by advocating positivity, success, and stability.

4.2 Contrasting social media and Vietnamese journalism.Social media is the opposite of Vietnamese journalism in six aspects: function, content, the concept of freedom, content generators, legislative framework, and cost. First, in term of function, while journalism serves as the propaganda instrument for the Party and Government, social media is a communication tool to exchange ideas, free from information “gatekeepers” of journalism. Second, in term of content, mainstream media controls its content via CPTC’s agenda setting. To consolidate the belief in CPV’s leadership, Vietnamese journalism often promotes materials about positivity, good people, good deeds, agreement, development, success, and stability. Meanwhile, UGC turns social media into a platform for the diversity of thoughts and opinions. Negativity, controversy, and disagreement are not purposely excluded from social media. Social media is the platform for content about social debates, while Vietnamese journalism reflects top-down decisions and consensus.

Third, freedom of expression on Vietnamese journalism is framed within the control of the Party and Government. On social media, free flows of information lead to freedom of expression. Fourth, in terms of content generators, Vietnamese journalism is produced by Party-accredited journalists who own press cards issued by the Government. In contrast, the content of social media is created by non-professionals. This is the reason why Vietnam always refutes the ranking of World Press Freedom Index reported by Reporters Without Borders (RSF). In 2018, Vietnam ranked the 175th in press freedom, out of 180 countries. Vietnamese media officials said that the poor ranking results from the fact that RSF considers both journalists and social media users as reporters, while the Vietnamese authority thinks only those with press cards are reporters.11

Fifth, in terms of the legislative framework, Vietnamese journalism is regulated within the framework of the Press Code, while social media is mainly self-regulated. Legal documents to monitor social media are underdeveloped, including Decree No. 97 and 72 and some articles of the Penal Code. The Cyber Security Law has newly been enacted in June 2018.12 Before that, social media, in general, has been decentralized, self-controlled and regulated by the community rather than a specific social media law. Sixth, in term of administration costs, Vietnamese journalism organizations are units in CPV and Government machinery. As such, journalism relies on the budget it receives from the Government for its performance, salaries for journalists and staffs, office renting, equipment, media production costs, and so on. In contrast, social media runs on free-of-charge or lightweight designed platforms.

4.3 Contrast in social power structure.The influential religion of the country is Mahayana Buddhism (Irwin, 1996, p. 116; Schober, 2012, p. 10). The religion encourages peace, kindness, and harmony, and avoids hatred and delusion (Harvey, 2001, pp. 103-105). The second largest religious community is Confucianists (Irwin, 1996, p. 116). Confucianism was introduced to Vietnam during over one thousand years of Chinese colonization in Vietnam, from around the first century BC to the tenth century, and during some decades in the fifteenth century. Like Buddhism, Confucianism’s rituals try to maintain a harmonious relationship that can be achieved when patriarchal leadership is respected. In the Confucian patriarchal culture, the inferiors (lay people, younger people, women) obey the superiors (governors, the elderly, men) (Irwin, 1996, p. 45). Further emphasizing the dominant role of the government in Confucianism, Goldin (2011, p. 23) interpreted Confucius’ statement “To govern is to correct” as “Government is inescapably a moral endeavor, and the ruler’s behavior has an irresistible influence on his subjects.”

Hofstede designed dimension of the Power Distance Index (PDI) to illustrate Asian countries’ attitudes toward hierarchy. According to Hofstede, a higher PDI is associated with the beliefs that hierarchy and inequality are appropriate and beneficial, and that authorities and seniors should not be challenged or even questioned (Irwin, 1996, p. 33). Hofstede’s educational website shows that PDI of Vietnam ranges from 70 to 85, indicating the culture of high acceptance of hierarchy and respect for the authorities and the elderly. Leadership acceptance is the foundation for social stability and economic development in Vietnam. Another cultural characteristic is the high or low-context communication as defined by Edward T. Hall (1976). Irwin (1996, pp. 40-41) claimed that Asian culture is based on high-context communication, implicitly through the context of particular situations, the relationship, and physical cues including nonverbal communication. High-context cultures are relatively formal, more reliant on hierarchies, and tend to be more deeply rooted in the past. Vietnamese culture is high-context; meaning can be interpreted mostly from nonverbal signals or the set-up in the physical environment of communication.

The contrast in the social power structure between the Vietnamese tradition and social media can be observed from two perspectives: respect for hierarchy and the context of communication. First, the Vietnamese tradition, with its high PDI, respects hierarchy; meanwhile, social media attacks hierarchy and promotes equal status among users. Buddhism commands people to sacrifice the self, and Confucianism teaches people to respect patriarchal leadership. Social media, on the other hand, is a tool that people choose to use to challenge authorities due to the flat hierarchy of its connection. Social media connections create a rupture in the social hierarchy. They erase the gaps between superiors and inferiors, thereby transforming power difference into equality. For example, leaders and subordinates, seniors and juniors, men or women all become Facebook “friends” regardless of the power distance between them.

Second, the Vietnamese tradition involves high-context communication; nonverbal clues and physical set-ups significantly contribute to the effectiveness of communication. Whereas, social media is low-context communication where meaning is often transferred through textual languages and discourse. As such, it is independent from the physical environment. Since it is highly text-based, social media is the territory of those who can communicate well by written language, such as journalists, scientists, scholars, and so on. This is why, at the dawn of social media in Vietnam, Yahoo! 360° blogs were first used by novelists and authors to share their stories, diaries, poems, and so on.

Since the essences of social media are in sharp contrast to the existent structures in Vietnamese journalism and culture, social media could be an active agent in creating opposite perspectives in the media industry, as well as in Vietnamese society. This section discusses the formation of a new journalism management structure and the political pluralism as impacts of social media.

5.1 The new form of journalism management structure.Besides the Party and Government-based journalism associations that are bounded in the structure of journalism management (see Figure 2), other journalism associations have been emerging on social media. For instance, searching on Facebook with keywords nhà báo (journalists) in February 2018, returns hundreds of Facebook groups for journalists. These groups could be categorized by geographic location (such as Nhà báo Nam Định tại Hà Nội, Journalists who were born in Nam Dinh and are working in Hanoi); age (Diễn đàn nhà báo trẻ, the Young Journalists Forum); hobbies (Hội nhà báo xăm mình, Association for Journalists with Tattoos); the topics they cover (Hội nhà báo viết về chính phủ, Association for Journalists Covering Governmental Issues); or political viewpoints (Hội nhà báo Độc lập, the Independent Journalist Association); and so on.

There are even associations of people who are against government-sponsored journalism, or groups for sharing second job opportunities for journalists. The rise of social media-based journalist associations increases the number of journalism organizations which develop outside of the journalism management structure, as presented in Figure 2. These social media-based professional associations impact the Party and Government journalism. For example, the Young Journalists Forum on Facebook has over 22,000 members as of February 2018, which is approximately equal to the number of members of the Party-based Vietnam Journalists’ Association. It hosts a professional journalism award, Giải Vành Khuyên (Zosterops Award), which is run by public voting on Facebook. Its members can nominate, analyze, and criticize news items, and financially contribute to the operation of the award.

The journalists’ discussions are no longer restricted within each newsroom but become highly routinized and mechanized across different newsrooms via social media. With increasing journalist engagement on social media, social media-based professional groups have established a self-regulating process, enabling the media to gain a rather independent status vis-à-vis the Party and Governmental political-administrative structure. On social media discussions, ordinary citizens participate on equal footing with government officials and experts, and impact the construction of public opinion. Independent media and inclusion of citizens in public discourse are two factors activating the right “rules of the game” which facilitate the existence of the public sphere (Habermas, 2006, p. 420).

5.2 The political opposition emerges on social media.The Facebook Page, Tôi và sứ quán (Embassies and Me) is one of the opposition forces that emerged on social media. It started in May 2015 when Lao Dong (Labor) newspaper published the first part of a news story about the wrongdoings of the Vietnamese Embassy in Belgium. Second part of the story was removed from the next Lao Dong newspaper issue because of the pressure from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). Second part was then published on a Facebook page titled “Embassies and Me.” Both the Lao Dong newspaper and the Embassy are units of the Party and Government management structure. Negativity and criticism towards the Party and Government are removed from journalism. Whereas, social media can publish the topic, because it is not governed by the same legislative framework that applies to journalism.

As of February 2018, 30,000 thousand people have joined “Embassies and Me.” On some specific days in July 2018, when some audio recording of the conversations between the Embassy officials and service users were posted on the Page, the number of members actively using the Page at the same time was over 15,000. A virtual community of clients using the services of Vietnamese Embassies around the world was formed. These services include but are not limited to issuing passports, visas, birth-death registrations, marriage certificates, citizenship documents, and public notary. Service fees were often unreasonably charged. “Embassies and Me” provides case-by-case guidance for its members to use the services at the right fees, get rid of red tape and bribery, and stop corruption in embassies.

“Embassies and Me” is structured like a multi-national organization. It has elected representatives in many countries. The general election is annually conducted to form a Page management board. Page members raise funds to pay for the lawsuits against the Embassies or MOFA staffs who perform their work inappropriately and even illegally. Specific rules and regulations are made for the Page. Page users send their representatives to MOFA and authorities’ meetings; they appoint spokespersons; issue press releases; and send petitions to the Party and Government. They publish handbooks for clients of embassy services and provide tips and tricks to work with Embassies. The Facebook Page has been performing the function of a counter Ministry of MOFA. The Page constantly checks the performance of the Embassies to gradually improve their work. Clients of Embassies’ services often consult with this Facebook Page before and during seeking service from the Embassies and MOFA.

Opposition parties do not exist in this single-party country. However, social media can facilitate the emergence of opposition groups. A trend of using social media for protesting the authorities has been observed. For example, the Facebook Page, Bộ trưởng Y tế hãy từ chức (Call for the Resignation of the Minister of Health) serves as a hub for criticism against the Minister and Ministry of Health; the Page, Bạn hữu đường xa, (Friends on the Far Road) serves against the Ministry of Transport and its Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) toll fee stations. Many government-initiated projects have faced waves of criticism on social media, such as the Facebook Page and blogs against the bauxite mining projects, or the Facebook Page against dumping industrial mud into the Binh Thuan seabed. Even projects initiated by local governments can be thwarted by national and international social media users. For example, the SaveSonDoong social media movement protested the Quang Binh Province’s plan of building a cable car to Son Doong cave; and Hanoi City’s project of felling trees has been impeded by the social media users of the Facebook Page 6700 người vì 6700 cây (6700 Men for 6700 Trees). In these examples, social media is the communication tool for protesters and activists confronting the CPV and governmental authorities.

In an interview with the Tuoi Tre newspaper in 2007, the former Minister of Information and Communication, Mr. Le Doan Hop,13 used the metaphor of the right-hand traffic to coin the term “the right side” for Vietnamese journalism. He promised “to create a smooth right-hand side for the media wheels to go.” Responding to the Minister’s metaphor, the well-known Vietnamese Fields Medal awardee, mathematician and University of Chicago Professor, Ngo Bao Chau commented on his Facebook account: “Only the sheep walk to the assigned sides, free humans don’t.” From this response, the public got used to the two new terms: báo chí lề phải (right-side journalism) for the Party and Government and báo chí lề trái (left-side journalism) for social media.

Social media enables opposition and serves as alternative media with content that is often neglected by traditional Vietnamese journalism. It promotes a non-hierarchical culture, confronting the Vietnamese tradition of respecting power and hierarchy. Therefore, confronting groups employ social media to protest the authorities. The pressure of cyber protest and social media activism results in changes to traditional Vietnamese journalism, facilitating the formation of public spheres and political pluralism. Before the Cyber Security Law, social media re-shaped the media landscape of Vietnam in a way that facilitates public participation in the political realm.

1 Link to the Facebook Page, Tôi và sứ quán: https://www.facebook.com/groups/toivasuquan/

2 Mr. Truong Minh Tuan was the Deputy Minister of Information and Communication (MIC) when he provided these statistics about journalism and social media in Vietnam. He was the Minister of MIC of Vietnam from April 2016 to July 2018.

3 In the article “Vietnam wants to control social media? Too late.” published on the New York Times on November 30, 2017, the author shares an opinion, “The government has at best been able to block Facebook at sensitive moments, such as when President Barack Obama visited Vietnam in May 2016 or during local protests over an environmental disaster. However, tech-savvy Vietnamese internet users have always been able to find workarounds.” Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/30/opinion/vietnam-social-media-china.html

4 The Internet ruptures often occur at the same time with important CPV events. However, it is often announced that the ruptures are caused by shark chomping. “Shark chomping cable” becomes a metaphor for the temporary technological barriers to the Internet during significant CPV events.

5 For example, there are some blogs disclosing the corruption cases of the top CPV leaders, such as chandungquyenluc.blogspot.com, danlambaovn.blogspot.com, and quanlambao.blogspot.com.

6 In mid-2017, the CPV first discussed about the merging (nhất thể hóa) of the two blocs the Party and the State. From mid-2017, the pilot merging was conducted at the district and commune level in Quang Ninh Province and at the commune level in Ha Giang province. However, as of the time of this writing, October 2018, the two blocks still perform the separated functions. The Party provides leadership, meanwhile the State performs management duties. As such, the two blocs are still separated and not yet merged at all three levels as of October 2018.

7 Website of Nhan Dan newspaper: http://en.nhandan.com.vn/

8 Website of Vietnam News Agency: https://vietnamnews.vn/

9 Website of Vietnam Television (VTV) https://vtv.vn/

10 Website of the Voice of Vietnam (VOV) https://vov.vn/

11 The Vietnam press sector has always refuted this ranking and other reports about Vietnamese press freedom by the Reporters Without Borders, Committee to Protect Journalists, Amnesty International, or the Human Rights Watch. It is claimed that the ranking and reports were merely “slanderous and ill-intentioned fabrications that go against the reality in Vietnam” (Quan-Doi-Nhan-Dan, 2002). This is largely because Vietnamese media officials do not consider citizens without press cards as journalists or reporters, and therefore believe that they should not be counted in the barometer of the RSF ranking. This conceptual gap stems from ideologies differences in journalism in Vietnam and in Western countries.

12 This study analyzes the context of Vietnamese media landscape before the Cyber Security Law, focusing on the period from 2013 to mid-2018 when government control over Facebook had not been technically and legislatively tightened.

13 Mr. Le Doan Hop was the Minister of MIC of Vietnam from 2007 to 2011.