2019 年 2 巻 p. 74-89

2019 年 2 巻 p. 74-89

Since 2010, the confrontation over the Senkaku Diaoyu Islands (S/D issue) dispute has greatly worsened Japan-China relations. Under these circumstances, public opinion has exerted a great influence on the progress over this issue by exerting pressure on the home governments. Preceding a discussion on the public opinion about the S/D issue, the first question that should be answered is when and how such public opinion began to be formed. Therefore, in the present study, I would like to provide answers about the formation process of the public opinion about the S/D issue in Chinese society.

Although previous studied offered some clues for discovering the answer to this question, identifying an exact time for when the public opinion was formed is overlooked.. In light of the importance of the S/D issue for Japan-China relations and in East Asia in general, a definite understanding of this issue will have important significance in various aspects. Therefore, in the present study, I would like to explore the answer using empirical analysis and literature survey based on the theory of political communication.According to the results of the analysis, this issue was widely reported for the first time by the Chinese media in the 1970s. However, this issue began to become widely known among the Chinese general people from 1990 onwards. Among various factors, one factor leading to the formation of public opinion is noteworthy. It was a change in the media environment, in particular the appearance of television.

Since 2010, China’s territorial issues have entered a new phase due to changes and interactions between two environments. The first environment could be regarded as a change in the situation of the territorial issues between China and its neighboring countries. Since 2010, there has been frequent friction over territorial issues between China and neighboring countries, but since such friction has also occurred in the past, it appears that the strained international situation alone is not a significant enough factor to cause such changes. During the same period, the transformation that has occurred in another field is becoming a major trigger for redefining the “reality” of the territorial issue surrounding China: a transformation in the media environment. As Jakobson & Knox(2010, p.41) indicated that “previously, the media was a tool exclusively available to officials. Now, with the advent of the Internet, interest groups and citizens can also utilize the media and the Internet to influence public opinion as well as each other.” As Inoue (2016, pp. 77-78) notes, the influence of public opinion on policy decisions in China has traditionally not been considered important,especially when compared to democratic countries. However, among the various factors influencing Chinese foreign policy currently, public opinion, which was not a formal actor in policy decision until recently, is becoming one of the factors that cannot be ignored in Chinese policy decisions.

In China, the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island issue (“the S/D issue”) between China and Japan could be seen as the territorial issue that was most affected by the interaction between the aforementioned environments. The boat collision incident1 that occurred in 2010 led to a collision between the national sentiments of the two countries (Ienaga, 2012, p. 46). Large-scale protests occurred throughout China. Furthermore, in 2012, which marked the 40th anniversary of the normalization of diplomatic relations between Japan and China, a series of conflicts between the two countries concerning “nationalization” triggered intense reactions in China. As a result, the public opinion phenomenon, symbolized by anti-Japanese demonstrations, demonstrated its influence in Chinese society.

Because of this, public opinion on the S/D issue in China has increasingly gained importance as a new research subject. The present study focuses on the process of the formation of public opinion on the S/D issue in China and aims to empirically clarify the influence of changes in the media environment on this formation.

Due to the 2010 boat collision incident and the “nationalization riot” of 2012, a significant amount of research has been conducted on the S/D issue from the viewpoint of public opinion.

Such research has focused mainly on two areas: media studies and foreign policy analysis. In media studies, existing research has attempted to analyze public opinion on this issue mainly focusing on the reporting characteristics of the Chinese media (e.g., Deng, 2013; Liao & Cai, 2013; Ding, 2013); this type of research is worthy of evaluation because it has clarified the involvement of the Chinese media. However, while media coverage, the effects of mass communication, and the formation of public opinion are related, these are not completely causal relationships. In other words, many studies have analyzed press coverage based on media studies, but there is hardly any empirical research on the relationship between media content and the consciousness of the Chinese people. On the other hand, research based on foreign policy analysis of China’s external behavior on the S/D issue has analyzed its implications and underlying causes. Although explanations were divided on what this external behavior indicates, it was almost universally recognized that public opinion pressures accompanying changes in the media environment played an important role (e.g., Beukel, 2011; Swaine & Fravel, 2011; Johnston, 2013; Swaine, 2013; Fravel, 2016). In other words, most existing studies on external behavioral studies focused on the influence of domestic public opinion on China’s external behavior; however, there is insufficient analysis on how such public opinion was formed.

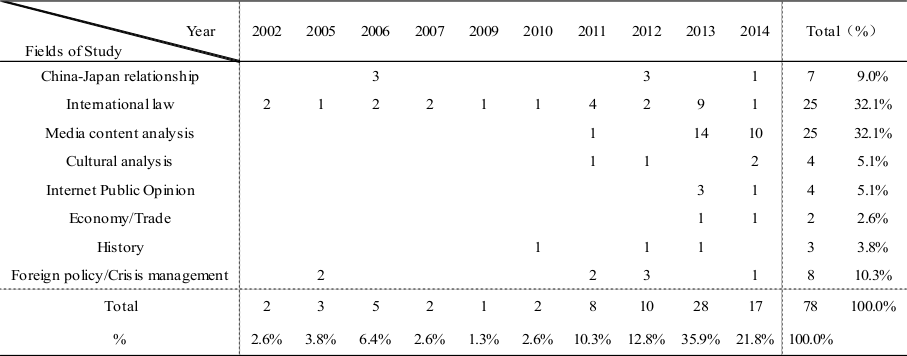

Note:

(1): This result is based on “WanfangData<(http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/)>” and “CNKI Scholar<http://scholar.cnki.net>.”

(2) Master’s thesis that includes “Diaoyu Island” in the title

Given these circumstances, based on the theory of the public opinion and mass communication, some clues about the formation of public opinion on the S/D issue can be found in existing research. For example, the Chinese government announced a formal statement on the S/D issue for the first time in December 1970 (Cai & Shuai, 2012). It can thus be inferred that public opinion on the S/D issue in China began to be formed in the 1970s. However, as media coverage does not necessarily lead to the formation of public opinion, it is difficult to determine a more definite timing only based on the above clues. Given these circumstances, in order to unravel how the awareness of the S/D issue spread across China, Chen (2011) analyzed respondents born between 1950 and 1980 from a survey conducted in the northeast of China. The study found that the number of people who first heard of the existence of the S/D issue increased notably in the first half of the 1990s (Chen, 2011, pp. 140-141). Although Chen presented noteworthy clues, the study findings were insufficient to accurately identify the exact period in which this public opinion was formed.

On the other hand, if we associate these results to the history of Sino-Japan relations on the S/D issue, clearer clues can be obtained. Two events occurred in the first half of the 1990s over the S/D issue that are noteworthy. One of them was the “the first lighthouse affair” that occurred in 1990 (e.g., Beukel, 2011; Ni, 2016). The other was the enactment of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone in February 1992, which expressly stipulates the Diaoyu Islands as being a part of China’s territory. If the existence of the S/D issue became widely known among the Chinese people in the first half of the 1990s, public opinion may have been influenced by the two above-mentioned events.

Although several studies have been conducted in different fields such as Japan-China relations, media coverage, popular consciousness, and the influence of public opinion about the S/D issue, few studies have focused on the relevance of the combinations of these research results. Therefore, while academic interest in public opinion on the S/D issue has been increasing in recent years, when and how such public opinion began to be formed in China remains unclear. Therefore, this paper attempts to reveal the background and timing of when public opinion on the S/D issue began to be formed in China based on theories on mass communication and public opinion formation.

In modern politics, all political regimes require public support (Kurokawa, 2010, p. 125). In other words, public opinion can be a tool not only for those in power but also of citizens themselves (Yashuno, 2006, p. ii). “Public opinion” is defined in many ways in Japan, including “opinions on social events, issues” (Kabashima, Takeshita, & Serikawa, 2007, p. 116), “opinions that are recognized as influential with respect to public issues” (Ooishi, 2014, p. 19), and “collective opinion commonly shared with a large number of people on certain affairs” (Kurokawa, 2010, p. 130). The common denominator is that it is a collection of recognized opinions; therefore, “public opinion” indicates “a consensus reached after careful deliberation by intelligent and knowledgeable citizens” (Yashuno, 2006, p. ii). However, it may also be an aggregation of emotional moods formed by the influence of mass media. Sato (2008, pp. 23-35) notes that in recent years, there has been a tendency to confuse the difference between “public opinion” and “popular sentiment” in Japanese society, which makes it especially important to distinguish between the two.

The most influential tool of mass media is said to be its “public opinion formation ability” (Kabashima et al., 2007, p. 33). Public opinion begins with the social cognition of people on public issues. In many cases, it is caused by mass communication (Manabe, 1983, p. 159). Cognition is experiential knowledge gained through learning and the evaluation of one’s beliefs (Sakaki, 2004, p. 89). In this study, the cognition of the Chinese people about the existence of the S/D issue is regarded as the first stage of public opinion formation.

Mass media has the ability to initiate public opinion by presenting social topics to the public, often referred to as agenda-setting. A two-step process, transmission and acceptance, underlie the formation of public opinion. Generally, these two processes are integrated by various media. “One of the most critical aspects in the concept of the agenda-setting role of mass communication is the timeframe for the creation of public awareness and concern of salient issues” (Freeland, 2012, p. 3).

3.2 Relationship Between Politics and the Media in ChinaBased on the above theoretical basis, public opinion about the S/D issue in China began with the cognition of Chinese people of the existence of the S/D issue, which was a consequence of media agenda-setting. In order to understand the agenda-setting on the S/D issue, it is necessary to understand the relationship between the media and politics in China. Liu noted that, first, integration of the media into political power is a prominent feature of political communication in China (Liu, 1998, p. 15). Media coverage in China must comply with the provisions established by the government. In particular, in the case of important political and diplomatic issues, “the media coverage must report in strict accordance with the relevant rules stipulated by the Party Central Committee and the State Council” (Xi, 2008, p. 173). Important political diplomatic issues are usually reported with great uniformity by the Xinhua News Agency and the People’s Daily (Watanabe, 2008, p. 74). Therefore, the Chinese government has had exclusive influence over the formation of the public opinion on the S/D issue through its involvement in setting the timeframe for salient issues and the creation of public awareness.

3.3 Research QuestionsBased on the theory discussed so far, this study formulated the following research questions to verify when public opinion about the S/D issue began to be formed in China:

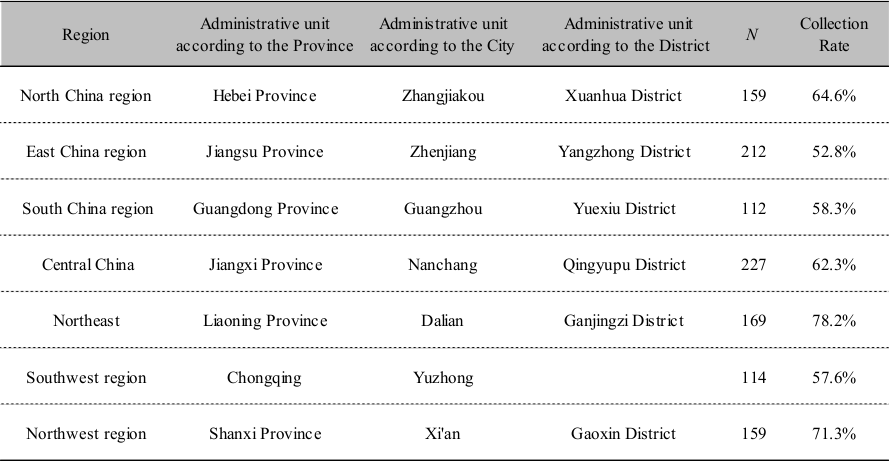

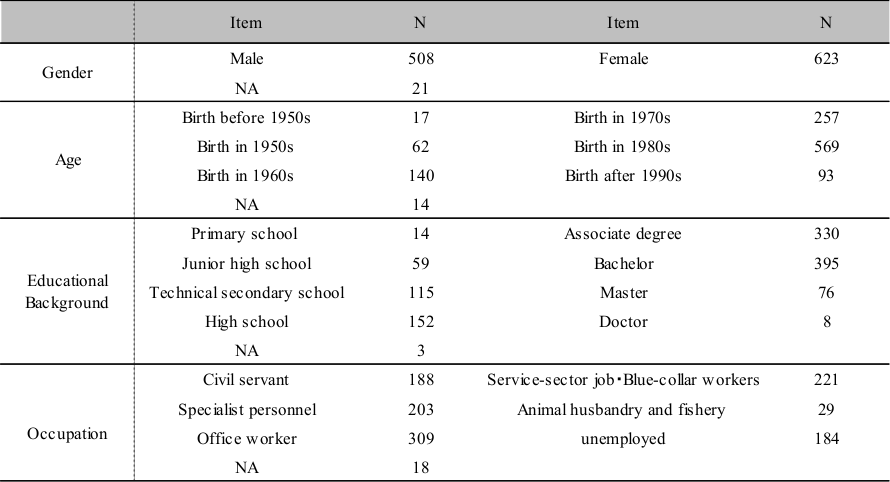

Analysis will be based on data collected from part of a survey called “Media Usage and Foreign Images” in China from May to July 2012. Residents over 18 years of age in seven regions of mainland China were surveyed using the multistage extraction method. A questionnaire administered to 1,152 respondents was employed using the collective survey method. The details are as follows.

The survey was conducted from May 20 to July 25 2012 in mainland China (except Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). The extraction of samples was performed in multiple stages in order to suppress sample bias. Specifically, the surveys were conducted in seven regions, namely Northeast, North China region, East China region, South China region, Central China, Northwest region, Southwest region. Administrative units were extracted according to the province, city, and district respectively from each area.. Finally, information about sites of large-scale collective housing where various age groups cohabit was extracted, and the survey was conducted using the placement-method and the group survey method for the residents aged over 18 years. Tables 2 and 3 present the details collected through the questionnaires.

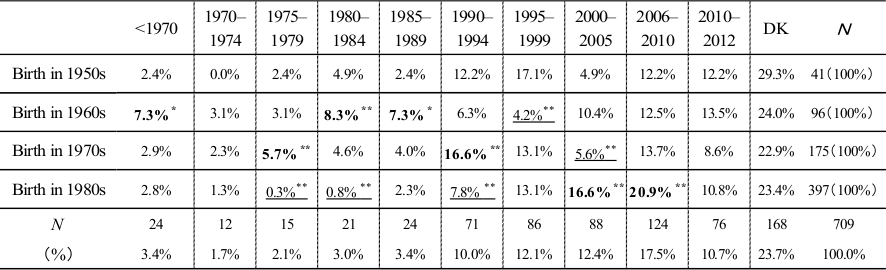

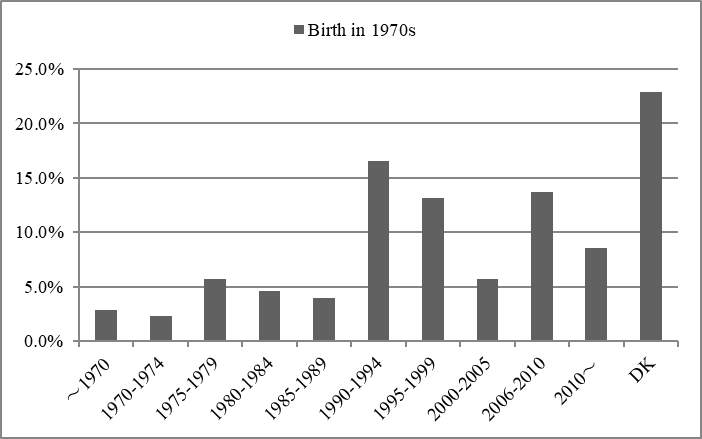

This survey was conducted during the period when conflicts between China and the Philippines were escalating over the Scarborough reefs (Huangyan Island in Chinese). Accordingly, question items related to the S/D issue were incorporated into the questionnaire. One of the questions was as follows, “When did you first hear about the S/D issue?” The response options were as follows: <1970; 1970–1974; 1975–1979; 1980–1984; 1985–1989; 1990–1994; 1995–1999; 2000–2005; 2006–2010; 2010–2012; and DK (don’t know)2. Based on the above survey results, this paper will reveal when public opinion about the S/D issue began to be formed in China.

4.2 Factor 1: Agenda-Setting Regarding the S/D IssueAs mentioned earlier, the originator of political communication in China on important political and diplomatic issues such as S/D is neither individual journalists nor media groups, but a party and the government. In other words, especially in the traditional media era, only the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese Government have the capability of initiating the communication process on the S/D issue. Therefore, this study will reveal the timeframe of the agenda-setting in China by studying the reports on the S/D issue in the People's Daily. Specifically, articles that included the keyword “Diaoyu Island” in the headline were extracted from all the articles published in the People’s Daily from May 15,1946 to December 31, 2014.

4.3 Factor 2: Media EnvironmentIn social science, mass media mainly refers to newspapers, magazines, television, and radio (Tsuyuki & Nakagawa, 2004, p. 25). Since the late 1990s, the use of Internet, personal computers, mobile phones, etc., began to spread globally. As a result, the mass communication phenomenon in modern society has become increasingly “multi-channelized” (Shimizu et al., 2012, p. 13). This study regards books, newspapers, magazines, television, radio, mobile phones, and the Internet as the media responsible for mass communication on the S/D issue based on the method of the mass communication survey (Sakamaki, 2007). Specifically, this paper will summarize the change in the media environment in China based on all the issues of the China Statistical Yearbook that has been published since 1983.

4.4 Factor 3: Major Social Incidents Surrounding the S/D IssueMajor social incidents surrounding the S/D issue will be summarized based on the chronology of those incidents (Urano, 2005).

As Table 4 reveals, there is a significant association between the first time that people heard about the S/D issue and their year of birth(χ2(30)=89.15、p<.001). Respondents born in the 1960s and 1970s first heard about the S/D issue primarily in the first half of the 1990s or in the 1980s, while respondents born in the 1980s heard about it after 2000.

Note:

(1) χ2(30)=89.15, p<.001

(2) According to the results of the residual analysis, the figures in bold are significantly higher than the underlined figures.

Figures 1 to 4 reveal that in addition to the respondents born in the 1960s, the number of respondents who heard about the S/D issue for the first time has increased significantly since the early 1990s. As explained in the theoretical introduction section, public opinion begins with people’s social perception of public issues. Based on the above results, we can conclude that the public opinion about the S/D issue has gradually grown in China since the first half of the 1990s. If such public opinion emerged in the first half of the 1990s, it is conceivable that the Chinese media presented relevant reports on the S/D issue to the public during the same period.

Figure 1. Time periods during when the respondents born in the 1950s first heard about the S/D issue.

Figure 2. Time periods during when respondents born in the 1960s first heard about the S/D issue.

Figure 3. Time periods during when the respondents born in the 1970s first heard about the S/D issue.

Figure 4. Time periods during when the respondents born in the 1980s first heard about the S/D issue.

As Table 5 indicates, the coverage on the S/D issue in China began in the 1970s. Overall, the relevant coverage surrounding this issue was mainly concentrated in five periods: 1971–1972, 1990, 1996–1997, 2003–2005, and 2010–2012. Outside those five periods, the People’ s Daily has had almost no coverage on the S/D issue. These periods overlap with the period during which there was conflict between the two countries over the S/D issue.

Note:

(1) “Articles with S/D in headlines” refers to an article of the People’s Daily that includes the keyword “S/D” in the headline.

(2) “Articles with Japan in headlines” refers to an article of the People’s Daily that includes the keyword “Japan” in the headline.

(3) “Ratio” is a number indicating the proportion of both. The higher the figure of this ratio, the higher the proportion of the S/D issue in Sino-Japanese relations.

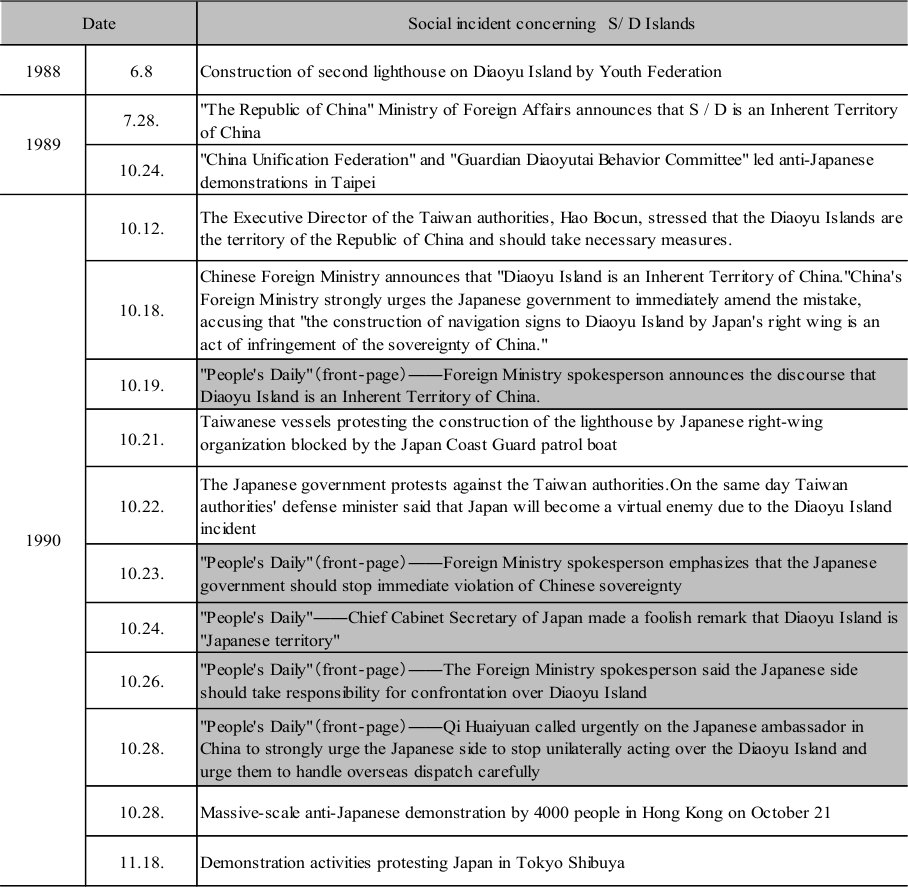

As Table 5 presents, there is an interval of about 20 years between the first peak period that began in the 1970s and the second peak period that began in 1990. However, since 1990, agenda-setting concerning the S/D issue reached a peak approximately every seven years. Among the five periods, 1990 is particularly noteworthy: over ten days in October, five headline articles were posted, four of which were on the front page—of the People’s Daily. It is not difficult to imagine that the characteristics of People’s Daily’s coverage on this issue could almost represent the characteristics of other Chinese media.

In China, although the media coverage around the S/D issue began in the 1970s, why did the acceptance process begin in the first half of the 1990s? It appears that there is a certain relationship between this phenomenon and the changes that occurred in the media environment.

5.3 Changes in the Media EnvironmentTable 6 presents the changes in the Chinese media environment since the beginning of 1970. As mentioned earlier, the first two peaks of the coverage of the S/D issue appeared in the early 1970s and in 1990. Compared with 1972, in the remaining three peak periods, the number of books, newspapers, and magazines in China increased by approximately nine times, eight times, and thirty times, respectively. Specifically, the number of books, newspapers, and magazines increased from 8,800, 185, and 194 immediately before the peaks to 80,200, 1,444, and 5,751, respectively, immediately after the peaks. However, changes took place not only in the print media,but also in the electronic media. Compared with the 1970s, the emergence of television was revolutionary in the media environment during this period. As Table 6 indicates, the TV penetration rate in China’s urban areas in 1990 reached 59%.

After World War II, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, television began to spread rapidly in the United States, Europe, and Japan (Yoshimi, 2004, p. 181). However, unlike the developmental process of these countries, it was not until the mid-1980s that television began to spread in China. Since television is a medium that conforms to the mass society (Ooishi, 2011, p. 91), it is conceivable that the expansion of the television would have greatly promoted the formation of mass society in China. From the above results, we can conclude that changes in the media environment during this period, especially the emergence of television, undoubtedly played a very important catalytic role in beginning to form public opinion about the S/D issue in China.

During the third reporting peak on this issue, it can be assumed that the rapidly developing traditional media played a more powerful role in communication. After the 2000s, the conflict between China and Japan on this issue, combined with the role of various new media and communication tools, greatly accelerated the indirect intervention of ordinary Chinese people in this process.

5.4 Major Social Incidents Surrounding the S/D IssueIn order to clarify why Chinese media reported on the S/D issue again in 1990, we will focus on the Sino-Japanese relationship over the S/D issue.

The Japan Youth League visited the islands in the 1990s to maintain a lighthouse on Diaoyu Island that was first built in 1978. In response, individuals from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Mainland China sought to land on the S/D islands to support China’s claims (Fravel, 2010, p. 152). In September 1990, the confrontation between Japan and Taiwan escalated, and the Chinese government made a series of intensive statements. As mentioned above, in only ten days, the People’s Daily published five headline articles, four of which were posted on the front page.

Additionally, at this time, the Chinese media environment had undergone major changes. In addition to major developments in print media, TV had also emerged. In particular, the penetration rate of television reached a very high level in large cities such as Beijing and Shanghai and eastern areas where economic development had been relatively advanced (Zhang, 2008, p. 216). As a result, the existence of the S/D issue began to be widely known among Chinese people since 1990. In other words, from that time, public opinion on the S/D issue began to increase in China.

This research focused on the formation of public opinion on the S/D issue in China and empirically clarified the influence of changes in the media environment on the formation of such public opinion. The results are as follows.

In China, the coverage of the S/D issue began in 1970 and peaked from 1971 to 1972 for the first time. Following that, the coverage of the S/D issue disappeared from the People’s Daily for a long time. Although the relevant reports appeared in the People’s Daily between 1979 and 1982, the intensity of the reporting was weak and the tone very mild. On the other hand, the media environment did not develop extensively and remained at a low level of development in China in the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, those who knew about the existence of the S/D issue were relatively few in number.

Although conflict occurred again in 1978 during negotiations between Japan and China on the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, it appears that such conflicts did not penetrate deeply into the general public consciousness, because the Chinese media were not actively reporting on it (e.g., Tretiak, 1978; Shaw, 1999; Koo, 2009). The reemergence of the crisis occurred in 1990, when the Japan Youth League applied for a lighthouse to be constructed on the disputed island to make Japan’s ownership of the island official (Downs & Saunders, 1998). This series of actions triggered a strong protest in Taiwanese society. In the case of Japan and Taiwan’s escalation of the confrontation and friction around this issue, the Chinese government issued a series of statements beginning in October 1990, and the reporting in the People’s Daily, as promulgated by the Chinese government, was the most concentrated reporting on the S/D issue since the early 1970s. In addition, due to the rapid development of traditional media since the 1980s, especially the emergence of television, information related to the S/D issue greatly penetrated the general public’s consciousness. However, the Chinese government imposed a media blackout on the public protests in Taiwan and banned similar protests within China. Students in Beijing learned about the protests through the BBC and Voice of America (Beukel, 2011, p. 12). This also shows us one aspect of the impact of changes in the media environment on the spread of the S/D issue in Chinese society. Through the interaction of the series of factors mentioned above, the existence of the S/D issue between China and Japan came to be widely known among the Chinese people. In other words, since 1990, public opinion on the S/D issue began to rise in Chinese society.

The “boat collision incident” that occurred in 2010, and particularly the “nationalization riot” of 2012 triggered an academic interest in the public opinion on the S/D issue. According to the author’s investigation, many previous studies have focused on the media coverage and the influence of domestic public opinion on China’s external behavior.

In media studies, many studies have analyzed press coverage based on media studies, but there is hardly any empirical research on the relationship between media content and the consciousness of the Chinese people. Most existing studies on external behavioral studies focus on the influence of domestic public opinion on China’s external behavior; however, there is insufficient analysis on how such public opinion is formed. Although some clues about the formation of public opinion on the S/D issue could be found in existing research based on the theory of public opinion and mass communication (e.g., Cai & Shuai, 2012; Chen, 2011; Beukel, 2011; Ni, 2016), as Chen (2011, pp. 140-141) indicates that the existence of the S/D issue became widely known among the Chinese people in the first half of the 1990s, a more definite timing is nevertheless difficult to determine.

Generally speaking, although there have been many studies in different fields such as Japan-China relations, media coverage, popular consciousness, and the influence of public opinion about the S/D issue, few studies have focused on the relevance of the combinations of these research results. In other words, while some studies presented clues that are noteworthy, these are insufficient to accurately identify when and how public opinion on the S/D issue began to be formed in China. Given these circumstances, the present study addressed the gap in the existing literature on when and how public opinion on the S/D issue began to be formed in China, based on the theories on mass communication and public opinion formation, as well as the data from part of a survey conducted in 2012.

The study has some limitations. First, the formation and evolution of public opinion on the S/D issue is a complex systemic process. Although this paper revealed the background and timing of when the public opinion on the S/D issue began to be formed in China, it does not explain how this public opinion evolved since 1990. Second, because the survey consisted of urban residents, the generalizability of our results to other populations, such as rural populations, is potentially limited. In addition, we used a self-rating questionnaire, which is an area of potential bias. As a self-rated response is not an objective evaluation, the participants’ response might cause a selection bias. Nonetheless, self-rated responses are considered to be highly credible for most respondents, as an existing study had pointed out the feature of the same tendency (e.g., Chen, 2011). Third, as mentioned above, in China, only the CPC and the Chinese Government have the capability of initiating the communication process on the S/D issue. Therefore, this study clarified the timeframe of the agenda-setting in China by reporting on the S/D issue in the People’s Daily. It means that this study only focused on the macroscopic feature of the public opinion on the S/D issue. In order to better prove the credibility of this study and reveal the microscopic features of the public opinion on the S/D issue, we need more empirical findings to support the present study.

Since 1990, conflicts and confrontations between China and Japan on the S/D issue have occurred about every seven years, though the S/D dispute appears to have stabilized since late 2013. Whether this stability can be maintained will be a test of the wisdom and communication competence of the two countries. On the other hand, as the public opinion on the S/D issue in China has increasingly gained importance as a new research subject, it is very important to combine studies from different fields into one field. In other words, interdisciplinary research must form the core of future studies on this topic.

1 The boat collision incident occurred on the morning of September 7, 2010, when a Chinese trawler operating in disputed waters collided with the Japanese Coast Guard’s patrol boats near the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. The collision and Japan’s subsequent detention of the skipper resulted in a major diplomatic dispute between China and Japan.

2 The question was asked in Chinese as follows. 您最早听说钓鱼岛问题是在以下哪一个时期? 1.1970年以前 2.1970~1974年 3.1975~1979年 4.1980~1984年 5.1985~1989年 6.1990~1994年 7.1995~1999年 8.2000~2005年 9.2006~2010年 10.2010年以后 99.我不知道