2015 Volume 79 Issue 10 Pages 2278-2279

2015 Volume 79 Issue 10 Pages 2278-2279

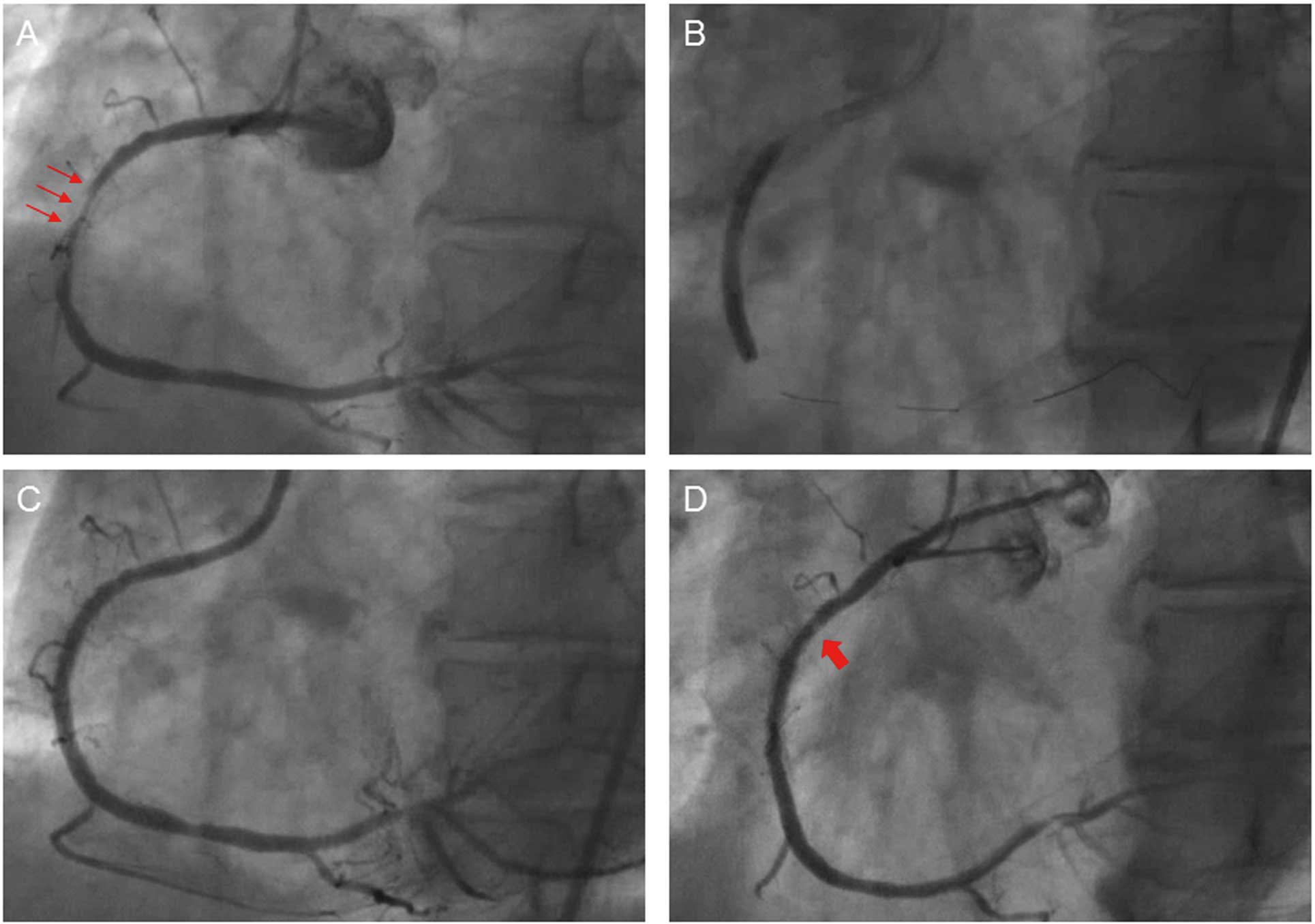

A 70-year-old man received a 3.0×33-mm sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) implant for in-stent restenosis of a bare-metal stent (Figures 1A–C). Coronary angiography was carried out 94 months later, which showed translucency at the proximal edge of the SES (Figure 1D). Coronary angioscopy (CAS) demonstrated presence of light yellow material with an irregular surface protruding into the lumen (Figure 2A). It was also noted on optical frequency domain imaging (OFDI) that the protruding material showed some attenuation in depth and it was partially covered by a surface layer with a clear border (Figure 2C). Judging from these findings, we diagnosed this material as representing a calcified nodule. Follow-up catheterization was performed again 105 months after SES implantation. CAS demonstrated red thrombus layered over the calcified nodule (Figure 2B; Movie S1). Lumen area narrowing was detected at the site of the calcified nodule on OFDI (3.47 mm2→3.04 mm2; Figure 2D).

(A) Coronary angiography showing severe stenosis at the bare-metal stent (BMS) implantation site of the right coronary artery (small arrows). (B) A 3.0×33-mm sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) was implanted at the BMS restenosis site. (C) Good dilatation was obtained after SES implantation. (D) Coronary angiography done 94 months after SES implantation showed translucency at the proximal edge of the stent (large arrow).

(A) Coronary angioscopy at 94 months after sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) implantation showing light yellow material with an irregular surface protruding into the lumen (arrows). (B) Coronary angioscopy at 105 months after SES implantation showing red thrombus layered over the calcified nodule (arrows). (C) Optical frequency domain imaging (OFDI) at 94 months showing that the protruding material showed some attenuation in depth and was partially covered by a surface layer with a clear border (arrows). (D) OFDI at 105 months after SES implantation showing that the protruding material had some attenuation in depth (arrows), and lumen area narrowing at the site of the calcified nodule (3.47 mm2 →3.04 mm2).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of calcified nodule rupture in vivo. One of the underlying mechanisms of arterial calcification is inflammation,1 and a previous study showed that inflammation may be observed on pathology after SES implantation.2 The present calcified nodule may have occurred in response to the inflammation caused by SES implantation. It is possible that the material was organized thrombus but, because dynamic intra-vascular status can be visualized on CAS,3–5 judging from the angioscopy, the mobility was poor compared with the organized thrombus. Therefore, this material was identified as a calcified nodule. Hao et al reported on the histopathology of calcified nodule and found that in addition to calcification, neovascularization within a myxomatous matrix was observed.6 Libby observed that intraplaque neovascular channels are prone to rupture, and stated that some episodes of sudden plaque expansion may result from hemorrhage due to such microvessel rupture.7 In the present case, intraplaque hemorrhage within the calcified nodule followed by lumen narrowing, was suggested by the red thrombus layered over the calcified nodule. Therefore, we speculated that this phenomenon may be due to rupture of calcified nodule. Calcified nodule can be one of the factors associated with very late stent thrombosis, especially after drug-eluting stent implantation. Furthermore, given that silent plaque rupture causes stenosis,8 calcified nodule can become a cause of late catch-up. We should provide close follow-up for patients with calcified nodule.

Name of Grant: None.

Supplementary File 1

Movie S1. Coronary angioscopy of the calcified nodule 105 months after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation, showing red thrombus layered over the calcified nodule.

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0228