2015 Volume 79 Issue 5 Pages 1044-1051

2015 Volume 79 Issue 5 Pages 1044-1051

Background: This study evaluated the mid to long-term durability and hemodynamics of the small-size Mosaic bioprosthesis, a third-generation stented porcine bioprosthesis, for aortic valve replacement (AVR).

Methods and Results: From 2000 to 2012, 207 patients (117 women; age, 74±8 years; body surface area, 1.48±0.25 m2) underwent AVR with a Mosaic bioprosthesis. The mean follow-up period was 3.5±2.7 years (maximum, 12.4 years) and the follow-up rate was 93.7%. A 19-, 21-, 23-, 25-, and 27-mm prosthesis was used in 103, 53, 35, 13, and 3 patients, respectively. The measured effective orifice area was 1.17±0.25, 1.29±0.19, 1.39±0.24, and 1.69 cm2 for the 19–25 mm prostheses, and the mean transvalvular pressure gradient was 19.4±6.0, 18.5±5.8, 16.5±7.3, and 13.2±2.9 mmHg, respectively. The left ventricular mass regression was significant (P<0.05) with rates of 74.6±18.8%, 75.5±30.2%, 68.1±30.5%, 55.9±12.9%, and 49.2%, respectively. The 30-day mortality rate was 1.9% and the 5- and 10-year actuarial survival rates were 86.0% and 73.7%, respectively. Valve-related comorbidities occurred in 3 patients (structural valve deterioration [SVD] in 1 after 7.2 years, and prosthetic valve endocarditis in 2). Freedom from SVD at 10-year was 96.7%.

Conclusions: The mid to long-term performance of the small Mosaic bioprosthesis was satisfactory, with excellent hemodynamics and few valve-related adverse events. (Circ J 2015; 79: 1044–1051)

Aortic valve replacement (AVR) with a bioprosthesis is the standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis, even in the era of transcatheter AVR (TAVR).1,2 Although the CoreValve clinical trial showed that 2-year survival was better after TAVR than after standard AVR in patients with high surgical risk, the long-term durability of TAVR is unknown.3 Standard AVR is still the first-line treatment for patients without high surgical risk, even in the old. As the life expectancy of elderly patients is increasing, long-term durability of the bioprosthesis is a critical issue for patients undergoing standard AVR.

The Mosaic bioprosthesis (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA) is a third-generation porcine bioprosthesis with a low-profile stent, leaflet fixation at zero pressure in a predilated aortic root, and amino-oleic acid antimineralization treatment.4 These features are expected to improve valvular hemodynamics and durability. The Mosaic bioprosthesis has been reported to have excellent long-term clinical outcomes.5–8 However, the large-scale studies that examined long-term outcomes did not include many small prostheses, with only 0–6% of patients receiving a 19-mm prosthesis.5–8 The present study examined outcomes up to 13 years after 207 patients received a Mosaic bioprostheses, of whom 103 received a 19-mm prosthesis, to evaluate the long-term durability and hemodynamics of small prostheses in relatively small patients.

This study retrospectively reviewed prospectively collected data from the Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Japan. From 2000 to 2012, 1,112 patients underwent AVR at the Center, of whom 668 received a bioprosthesis (Carpentier-Edwards Perimount: 208, Medtronic Mosaic: 207, Carpentier-Edwards Magna including Magna EASE: 165, Medtronic Freestyle: 62, St. Jude Medical Epic: 18, St. Jude Medical Trifecta: 8). The body surface area (BSA) of each patient was calculated using the Mosteller formula.9 The main indications for surgery were aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation. The choice of aortic prosthesis was determined by the patient’s preference or according to the Japanese guidelines for choice of prosthesis in the aortic position, which indicate that patients older than 65 years or intolerant of warfarin are suitable for a bioprosthesis. The choices of bioprosthesis essentially depended on the surgeon’s preference, but a Mosaic bioprosthesis was the likely choice for patients with a small annulus.

Patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis were significantly more likely to be female (P<0.01), have a relatively small BSA (P<0.01), have aortic stenosis (P<0.01), and have a smaller left ventricular (LV) dimension on postoperative echocardiography (P<0.01) than patients who received a larger prosthesis.

Patients who subsequently underwent replacement of the prosthesis were censored on the date of the replacement procedure. We defined structural valve deterioration (SVD) as leaflet degradation requiring reoperation, which exclude prosthetic valve endocarditis. Follow-up was by structured telephone interviews, review of the hospital records, review of medical and echocardiographic documentation, and questionnaires sent to primary care physicians. The mean follow-up period was 3.5±2.7 years and the follow-up rate was 93.7%.

Procedures and Choice of Prosthesis SizeIsolated AVR was performed in 96 patients (46.4%). Concomitant procedures are shown in Table 1. The aortic bioprosthesis was implanted in the supra-annular position using pledgeted non-everting mattress sutures in all cases. Coronary artery bypass grafting was performed in 52 patients (25.1%) and aortic root enlargement was performed in 2 patients. The prosthesis size was chosen according to the annular size using the dedicated Mosaic sizer, taking care to avoid prosthesis-patient mismatch (PPM). The projected effective orifice area (EOA) was obtained from the manufacturer and the EOA index (EOAI) was calculated as projected EOA/BSA (Table 2). The mean EOAI in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis was 0.85±0.08 cm2/m2.

| 19-mm prosthesis (n=103) |

Other size prosthesis (n=104) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75.9±6.8 | 72.1±8.3 | <0.01 |

| Male/female | 20/83 | 70/34 | <0.01 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.4±0.18 | 1.59±0.18 | <0.01 |

| NYHA functional class | 2.2±0.6 | 1.9±0.6 | <0.01 |

| NYHA class III or IV | 19 (18.4%) | 12 (11.5%) | 0.18 |

| Indication for surgery | |||

| AS | 68 | 43 | <0.01 |

| AR | 3 | 33 | <0.01 |

| ASR | 25 | 25 | 0.99 |

| IE (PVE) | 1 (1) | 2 (0) | 0.99 (0.07) |

| SVD | 8 | 3 | 0.13 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 4 (3.9%) | 4 (3.8%) | 0.99 |

| Hypertension | 85 (82.5%) | 73 (70.2%) | 0.05 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 64 (62.1%) | 44 (42.3%) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (22.3%) | 24 (23.1%) | 0.99 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 34 (33%) | 18 (17.3%) | 0.01 |

| Old cerebral infarction | 12 (11.7%) | 9 (8.7%) | 0.5 |

| Renal insufficiency | 11 (10.7%) | 9 (8.7%) | 0.81 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 9 (8.7%) | 5 (4.8%) | 0.28 |

| Follow-up period (years) | 3.3±2.9 | 3.9±3.0 | 0.13 |

| Maximum | 11.7 | 12.4 | |

| Follow-up rate | 94.2 | 93.3 | |

| UCG follow-up period (years) | 3.1±2.8 | 3.9±2.7 | 0.08 |

| Preoperative echocardiography | |||

| AS/ASR | |||

| LVDd (mm) | 44.4±6.1 | 51.1±9.7 | <0.01 |

| LVDs (mm) | 27.2±6.1 | 34.0±10.4 | <0.01 |

| FS (%) | 38.8±7.3 | 35.0±9.0 | <0.01 |

| Peak PG (mmHg) | 95.4±33.3 | 81.3±28.9 | <0.01 |

| Mean PG (mmHg) | 56.0±20.0 | 48.5±18.3 | 0.02 |

| AVA (cm2) | 0.62±0.22 | 0.72±0.23 | <0.01 |

| AR | |||

| LVDd (mm) | 57.7±9.1 | 66.3±9.4 | 0.1 |

| LVDs (mm) | 40.7±6.0 | 47.1±10.6 | 0.31 |

| FS (%) | 29.3±2.5 | 28.1±7.8 | 0.79 |

| Peak PG (mmHg) | 37 | 30±10.3 | 0.57 |

| Mean PG (mmHg) | 28 | 16.7±6.7 | 0.28 |

| AVA (cm2) | NA | 1.98 | |

| Procedure | |||

| Isolated AVR | 48 (46.6%) | 48 (46.6%) | 0.99 |

| +CABG | 35 (34.0%) | 17 (16.3%) | <0.01 |

| +MVR | 7 (6.8%) | 10 (9.6%) | 0.61 |

| +MVP | 6 (5.8%) | 9 (8.7%) | 0.59 |

| +Maze procedure | 5 (4.9%) | 7 (6.7%) | 0.77 |

| +Graft replacement | 3 (2.9%) | 9 (8.7%) | 0.13 |

| +TAP | 5 (4.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | 0.5 |

| +Root enlargement | 2 (1.9%) | 0 | 0.25 |

| +ASD closure | 2 (1.9%) | 0 | 0.25 |

| +Pericardiectomy | 2 (1.9%) | 0 | 0.25 |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation or number of patients. AR, aortic regurgitation; AS, aortic stenosis; ASR, AS with regurgitation; ASD, atrial septal defect; AVA, aortic valve area; AVR, aortic valve replacement; BSA, body surface area; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; FS, fractional shortening; IE, infective endocarditis; MVP, mitral valvuloplasty; MVR, mitral valve replacement; NA, not available; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PG, pressure gradient; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis; SVD, structural valve deterioration; TAP, tricuspid annuloplasty; UCG, echocardiography.

| Prosthesis size (mm) | Projected EOA (m2) | Mean EOAI (cm2/m2) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 1.2 | 0.85±0.08 | 103 (49.8%) |

| 21 | 1.3 | 0.87±0.08 | 53 (25.6%) |

| 23 | 1.5 | 0.89±0.09 | 35 (16.9%) |

| 25 | 1.8 | 1.12±0.08 | 13 (6.3%) |

| 27 | 2.0 | 1.05±0.05 | 3 (1.4%) |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation. AVR, aortic valve replacement; EOA, effective orifice area; EOAI, EOA index.

Echocardiography was performed pre- and postoperatively and at follow-up. Postoperative data were obtained for 196 patients (95%) and follow-up data were obtained for 123 patients (59.4%). The mean follow-up period was 3.5±2.7 years. LV mass was calculated using the Devereux formula10 and was indexed to BSA to yield the LV mass index (LVMI). The postoperative EOA was determined by transthoracic echocardiography using the standard continuity equation.

Statistical AnalysisData are presented as the mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. The patients were divided into 2 groups: those who received a 19-mm Mosaic valve, and those who received another size of Mosaic valve (21, 23, 25, or 27 mm). Differences between groups were analyzed using the χ2 test or Student’s t-test, with P<0.05 considered statistically significant. Differences in LVMI according to time and valve size were evaluated by repeated-measures analysis of variance (repeated-measures ANOVA). Survival and freedom from SVD were determined by Kaplan-Meier actuarial analysis, and were compared between groups using the log-rank statistic. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). EZR is a modified version of R Commander designed to add statistical functions frequently used in biostatistics.

New York Heart Association functional class was significantly (P<0.05) improved for each prosthesis size: from 2.2±0.6 to 1.1±0.3 in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis, from 1.9±0.5 to 1.1±0.3 in patients who received a 21-mm prosthesis, from 1.8±0.6 to 1.2±0.4 in patients who received a 23-mm prosthesis, from 2.5±0.8 to 1.2±0.4 in patients who received a 25-mm prosthesis, and from 1.3±0.6 to 1 in patients who received a 27-mm prosthesis (Figure 1).

New York Heart Association functional class improved significantly (P<0.05) between the preoperative and follow-up evaluations for each prosthesis size (19 mm: from 2.2±0.6 to 1.1±0.3; 21 mm: from 1.9±0.5 to 1.1±0.3; 23 mm: from 1.8±0.6 to 1.2±0.4; 25 mm: from 2.5±0.8 to 1.2±0.4) except for 27 mm (from 1.3±0.6 to 1). *Significantly lower than the preoperative value.

The 30-day mortality rate was 1.9%; 2 patients died of LV rupture, 1 died of low output syndrome, and 1 died of mediastinitis (Table 3). There were 22 late deaths, of which 5 were from cardiac conditions. The patient who died of infectious endocarditis was counted as a valve-related death. The 5- and 10-year actuarial survival rates were 86.0±3.0% and 73.7±6.4%, respectively (Figure 2A). The overall survival curve was similar to the Japanese life expectancy curve for 74-year-old individuals published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. The survival rate was compared between patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis and patients who received another size of prosthesis (Figure 2B). The 5- and 8-year actuarial survival rates were 91.2±3.1% and 84.0±6.0%, respectively, in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis, and 80.1±4.8% and 64.3±9.8%, respectively, in patients who received another size of prosthesis, which was not a significant difference in survival between the 2 groups.

| n | |

|---|---|

| 30-Day mortality | Total 4 (1.9%) |

| Left ventricular rupture | 2 |

| Low output syndrome | 1 |

| Mediastinitis | 1 |

| Late mortality | Total 22 |

| Cardiac causes | |

| Heart failure | 2 |

| Sudden death | 2 |

| Infectious endocarditis | 1 |

| Cerebral bleeding | 1 |

| Non-cardiac causes | |

| Cancer | 3 |

| Pneumonia | 2 |

| Hepatic failure | 2 |

| Suicide | 1 |

| Sepsis | 1 |

| Other | 3 |

| Unknown | 4 |

AVR, aortic valve replacement.

(A) Overall survival curve compared with the Japanese life expectancy curve for 74-year-old individuals. The overall 5- and 10-year actuarial survival rates were 86.0±3.0% and 73.7±6.4%, respectively. (B) Survival curves for patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis and those who received another size of prosthesis. The 5- and 8-year actuarial survival rates were 91.2±3.1% and 84.0±6.0%, respectively, in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis, and 80.1±4.8% and 64.3±9.8%, respectively, in patients who received another size of prosthesis; which was not a significant difference in survival between groups. (P=0.24). (C) Overall freedom from structural valve deterioration (SVD). The 5- and 10-year actuarial rates of freedom from SVD were 100% and 96.7±3.3%, respectively. (D) The 5- and 8-year actuarial rates of freedom from SVD were 100% and 91.7±8.0%, respectively, in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis, and 100% and 100%, respectively, in patients who received another size of prosthesis. This was not a significant difference between the groups (P=0.22).

Late morbidity included chronic heart failure in 5 patients, requirement for a pacemaker in 5 patients, and cerebral infarction or bleeding in 4 patients. Valve-related comorbidities occurred in 3 patients, including SVD in 1 patient after 7.2-years (19-mm prosthesis), and prosthetic valve endocarditis in 1 patient after 0.5 years (21-mm prosthesis) and in another patient after 3.1 years (19-mm prosthesis).

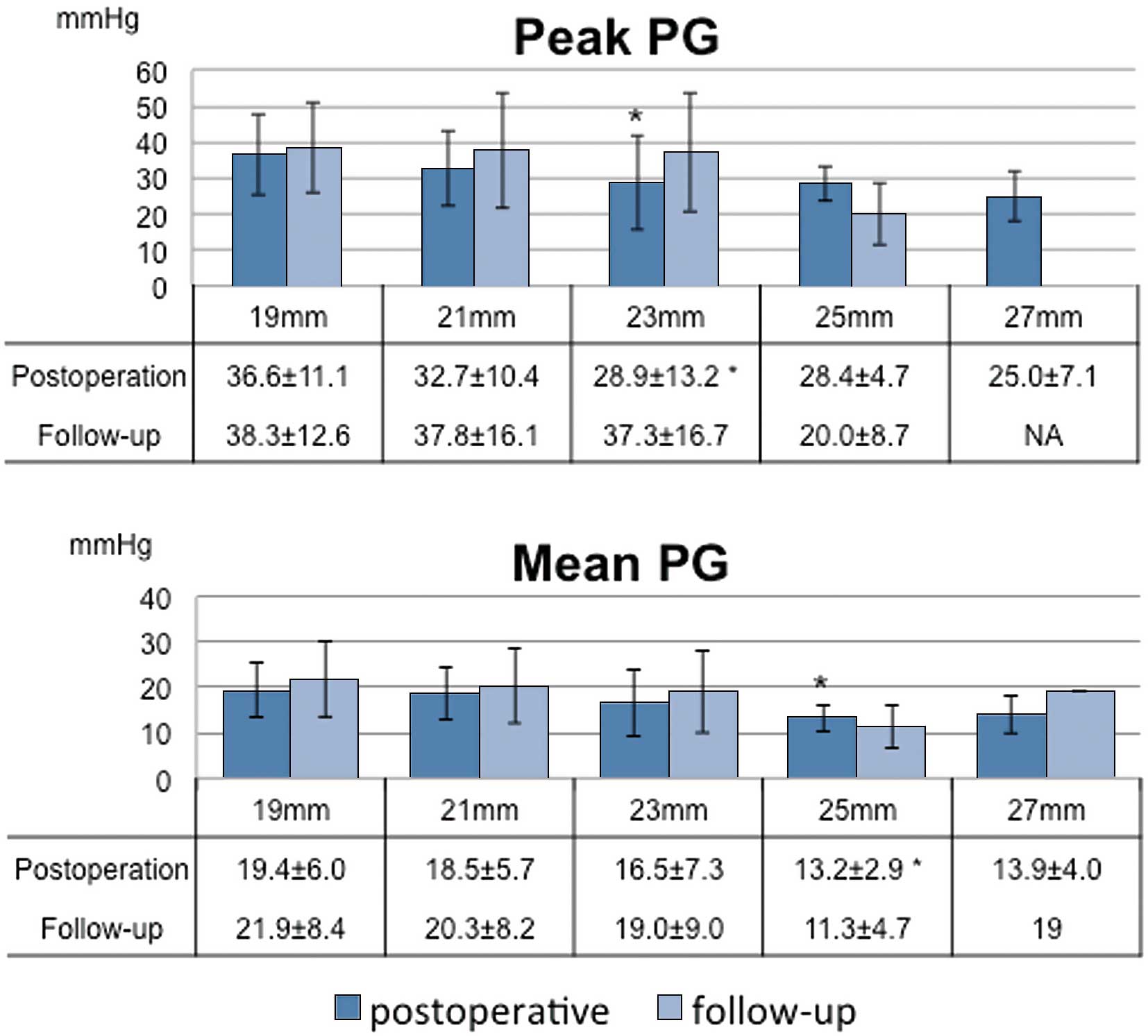

The 5- and 10-year actuarial rates of freedom from SVD were 100% and 96.7±3.3%, respectively (Figure 2C). SVD requiring reoperation occurred in 1 patient who received a 19-mm prosthesis, but there was no significant difference in the rate of freedom from SVD between patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis and those who received another size of prosthesis (Figure 2D). Postoperative echocardiography showed that the peak pressure gradient (PG) and mean PG were significantly higher in patients who received smaller prostheses. The peak PG was 36.6±11.1 mmHg in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis and 32.7±10.4 mmHg in patients who received a 21-mm prosthesis (Figure 3). The mean PG was 19.4±6.0 mmHg in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis and 18.5±5.7 mmHg in patients who received a 21-mm prosthesis. These values decreased gradually as the prosthesis size increased. There was a significant difference between the peak PG in patients who received the 19-mm and 23-mm prostheses (P<0.05), and between the mean PG in patients who received the 19-mm and 25-mm prostheses (P<0.05). The peak PG and mean PG were higher at follow-up than postoperatively for each prosthesis size except for 25 mm, but these differences were not significant. The measured postoperative and follow-up EOA values for each prosthesis size were similar to the projected EOA values (Table 4). The follow-up EOA values were smaller than the postoperative EOA values, but these differences were not significant.

Echocardiography performed postoperatively and in the follow-up period (mean, 3.5±2.7 years). The postoperative peak pressure gradient (PG) and mean PG were significantly higher in patients with the smaller prostheses (peak PG, 19 mm vs. 23 mm: P<0.05; mean PG, 19 mm vs. 25 mm: P<0.05). The PGs were slightly higher on follow-up echocardiography than on postoperative echocardiography. *Significantly lower than in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis.

| Prosthesis size (mm) | Measured EOA/EOAI (cm2/m2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Postoperative | Follow-up | |

| 19 | 1.17±0.25/0.84±0.18 | 1.09±0.26/0.78±0.17 |

| 21 | 1.29±0.19/0.87±0.13 | 1.20±0.26/0.81±0.21 |

| 23 | 1.39±0.24/0.86±0.16 | 1.24±0.33/0.76±0.20 |

| 25 | 1.69/1.08 | 1.57±0.33/0.89±0.17 |

| 27 | 2.37/1.18 | NA |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation. Abbreviations as in Tables 1,2.

The postoperative and follow-up LVMI values were significantly reduced compared with the preoperative values for each prosthesis size (all P<0.05) (Figure 4). The reduction in LVMI was 74±19% in patients who received a 19-mm prosthesis and 70±29% in patients who received another size of prosthesis, but this was not a significant difference between groups (P=0.315). Further comparison did not show a significant difference in LVMI regression among the different sizes of prosthesis (repeated-measures ANOVA, P=0.09).

Follow-up echocardiography showed a significant reduction in left ventricular mass index for each size of prosthesis (P<0.05). There was no significant difference in left ventricular mass index regression among the different sizes of prosthesis (repeated-measures ANOVA, P=0.09). *Significantly lower than preoperative values.

This study found excellent long-term survival and freedom from SVD in patients with a Mosaic bioprosthesis. Our study group had a mean age of 74 years, a follow-up rate of 93.7%, and 5- and 10-year survival rates of 86.0% and 73.7%, respectively. The survival curve of the study group was similar to that of 74-year-old individuals in Japan, suggesting that AVR with a Mosaic bioprosthesis is beneficial in patients with severe aortic stenosis. The Perimount and Mosaic bioprostheses have both been reported to have excellent long-term clinical outcomes.6–8,11 As studies of the Perimount bioprosthesis have longer follow-up periods (up to 25 years), this prosthesis has been used more often than the Mosaic bioprosthesis.12,13 However, Glaser et al reported no significant difference in late survival between patients with Perimount and Mosaic bioprostheses, even though severe PPM was more common in patients with the Mosaic prosthesis.5 Jamieson et al reported that the 12-year actuarial rate of freedom from SVD requiring reoperation in patients who underwent AVR with a Mosaic prosthesis was 91%,7 and Celiento et al reported a 13-year rate of freedom from SVD requiring reoperation of 89%.6 These excellent long-term outcomes combined with our 10-year rate of freedom from SVD requiring reoperation of 97% show that the Mosaic bioprosthesis is one of the first choices for standard AVR. Moreover, our data show that use of a 19-mm Mosaic bioprosthesis in relatively small patients is acceptable and has excellent long-term outcomes.

Bovine bioprostheses have been reported to result in better hemodynamic performance than porcine bioprostheses, with a lower transvalvular PG and greater LV mass regression.14,15 However, Suri et al reported that LV mass regression was similar in patients with bovine and porcine bioprostheses after 1 year, despite a higher transvalvular PG in patients with porcine bioprostheses.16 As the diameters of the bioprostheses and sizers are different for bovine and porcine valves, hemodynamics cannot be directly compared between same-sized Mosaic and Perimount bioprostheses. Seitelberger et al reported that in their prospective randomized study, the labeled valve size was smaller compared with the aortic diameter in the Perimount group than in the Mosaic group, and that the hemodynamic performance was similar for these 2 prostheses when the aortic diameter was used as the reference.17 In the present study, the postoperative mean transvalvular PG was 13–19 mmHg, and decreased with prosthesis size. Follow-up echocardiography showed a slight increase in PG associated with each increase in valve size, which may be explained by increased cardiac output in the late period. Avoidance of PPM is one of the most important factors in the choice of prosthesis to improve survival and avoid cardiac events, even for the aortic position or mitral position.18,19 As shown in Table 2, the mean EOAI in patients receiving 19-, 21-, and 23-mm prostheses was 0.85±0.08 cm2/m2, 0.87±0.08 cm2/m2, and 0.89±0.09 cm2/m2, respectively. According to the definition of PPM, severe PPM is less than 0.65 cm2/m2, and there were no patients in this entire cohort who had severe PPM. However, in general, PPM is defined as EOAI less than 0.85 cm2/m2.20 As such, almost half of the patients receiving a 19-mm, 21-mm or even 23-mm prosthesis had “PPM”, defined as EOAI equal to or less than 0.85 cm2/m2. These findings seem to be common in patients receiving a stented bioprosthesis, and consistent with previous reports.20 However, avoidance of severe PPM defined as EOAI less than 0.65 cm2/m2 without root enlargement, except in 2 patients, indicated that the Mosaic bioprosthesis provided a good EOA relative to the outer diameter. The strongest feature of the 19-mm Mosaic is that it can be implanted in patients with a smaller annulus that is unable to take a 19-mm Perimount bioprosthesis. In fact, the 19-mm Mosaic has a more flexible sewing cuff with slightly smaller internal diameter than the 19-mm Perimount bioprosthesis, which definitely makes it easier to implant and useful for a wider range of patients. Moreover, significant LV mass regression was achieved in the late period for each prosthesis size, including 19 mm. This result suggests that the 19-mm Mosaic bioprosthesis does not compromise hemodynamics if severe PPM is avoided.

The flexibility of the valve leaflets may explain the relatively high transvalvular PG despite significant LV mass regression. Kuehnel et al reported that in their in vitro measurements, the Perimount bioprosthesis had a lower mean transvalvular PG than the Mosaic bioprosthesis.21 However, according to the measurements done by Yoganathan et al,22 the porcine bioprosthesis tended to create more centralized flow fields with its flexible leaflets and reduce the levels of turbulent shear stresses, so as long as the peak PG is calculated by the peak velocity, the Mosaic bioprosthesis may provide higher peak PG. Because of the flexible leaflets, the Mosaic bioprosthesis had a shorter opening time, and the opening time was less dependent on cardiac output than with the Perimount bioprosthesis. Dzemali et al reported that in their in vitro measurements at low stroke volume, the closing time was shorter in the Mosaic bioprosthesis than in the Perimount bioprosthesis.23 Shorter opening and closing times result in a smaller closing volume and may result in less energy loss. Doppler echocardiography shows greater flow velocity through the Mosaic bioprosthesis than the Perimount bioprosthesis. The higher PG across the Mosaic bioprosthesis on Doppler echocardiography may also be explained by the pressure recovery phenomenon, especially in patients with a small prosthesis and a small aorta.24,25 The flexible leaflets of the Mosaic bioprosthesis can be opened with less energy than those of the Perimount bioprosthesis, and the resulting smaller turbulence may enhance the pressure recovery phenomenon. Use of the Mosaic bioprosthesis can therefore result in significant LV mass regression despite the relatively high transvalvular PG. Ito et al reported a case of high PG through a Mosaic bioprosthesis in the aortic position, which was as high as 60 mmHg by Doppler measurement but the peak-to-peak PG in this patient measured by catheter examination was only 15.1 mmHg.25 This finding may be explained by the pressure recovery phenomenon. As the patients with relatively high PGs in this study did not develop significant adverse events, the relatively high PGs may be traceable, because the Mosaic bioprosthesis tended to express higher PGs, despite excellent hemodynamics.

In addition to aiming for good hemodynamics and durability, ease of implantation is an important aspect to consider when selecting a prosthesis. The Mosaic bioprosthesis uses the Cinch implantation system, which draws the stent post in to provide better visualization and more room for tying knots. In the present study, there were no cases of significant paravalvular leakage with use of this system. Ease of implantation may be one of the factors contributing to the low 30-day mortality rate (1.9%) in these elderly patients, of which 60% required concomitant procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafting.26

Study LimitationsWe acknowledge that our study has several limitations. It was conducted retrospectively in a single center, and consequently included a limited number of patients. The mean follow-up period was 3.5±2.7 years, and thus, further observation is required to verify our conclusions. Furthermore, the choice of Mosaic bioprosthesis was left to the surgeon’s and patient’s preferences, although it was anticipated that patients with a small annulus would receive a Mosaic bioprosthesis. Therefore, a randomized study to compare the Mosaic prosthesis with other valves should be performed in the future.

In conclusion, the long-term performance of the Mosaic bioprosthesis was satisfactory, with excellent hemodynamics and few valve-related adverse events, including SVD. These advantages were not lost when using a small prosthesis, and the 19-mm Mosaic bioprosthesis is a suitable choice for relatively small patients. A longer follow-up period is necessary to definitively determine whether the relatively high PG across this valve compromises durability and hemodynamics in the very late period.

Grant: None.