2015 Volume 79 Issue 5 Pages 1100-1106

2015 Volume 79 Issue 5 Pages 1100-1106

Background: Red cell distribution width (RDW) is known to be associated with anemia and mortality in cardiovascular diseases, while anemia itself is related to increased mortality. RDW may also be related to cytokine activation. We investigated the potential of RDW to predict anemia-adjusted mortality in patients with adult congenital heart disease (ACHD) and we evaluated the relationships among RDW, anemia, and interleukin-6 (IL-6).

Methods and Results: This was a single-center, retrospective cohort study. Blood RDW and IL-6 levels were measured in 144 patients with ACHD (median age [interquartile range (IQR)], 28 [22–36] years), 84% in New York Heart Association class I/II. During a mean 4.8-year follow-up, 21 (15%) patients died of cardiovascular causes. Elevated RDW (>15.0%) correlated significantly with mortality risk in a univariate analysis (RDW hazard ratio [HR]: 1.570; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.208–2.040 per 1 standard deviation increase; P=0.001). Elevated RDW levels correlated significantly with increased anemia-adjusted mortality (adjusted RDW HR: 1.912; 95% CI: 1.369–2.670; P<0.001). The high RDW group had significantly elevated serum IL-6 levels (RDW >15%, median [IQR], 3.7 [0.9–13.9] pg/ml vs. RDW ≤15%, 1.4 [0.8–2.5 pg/ml]; P=0.001), as did patients with anemia (anemia, 1.9 [0.9–5.2] pg/ml vs. no anemia, 1.4 [0.8–2.5 pg/ml]; P=0.021).

Conclusions: Elevation of RDW may be related with increased IL-6 and anemia-adjusted cardiovascular mortality in patients with ACHD. (Circ J 2015; 79: 1100–1106)

An increase in the red cell diameter distribution width (RDW) indicates greater heterogeneity in the size of circulating erythrocytes (anisocytosis). An increased RDW value is used mainly in the differential diagnosis of microcytic anemia. A previous study described the relationship between increased RDW and iron-deficiency anemia in patients with heart failure, in the context of acquired heart disease.1,2 Although cyanotic and hypoxic patients with congenital heart disease often experience iron-deficiency anemia, the relationship between anemia and elevated RDW is unclear in adult congenital heart disease (ACHD).3

Editorial p 974

Recent studies have revealed that RDW is a strong predictor of all-cause mortality in various diseases, including cardiovascular mortality in older adult patients with acquired heart disease and patients with congenital heart disease.4–7 Although anemia may be a confounding variable in the relationship between RDW and cardiovascular mortality, it has not been clarified whether, after adjustment for anemia, RDW is a significant predictor of cardiovascular mortality in ACHD.

Anemia is often observed in chronic diseases such as infection, cancer, autoimmune disease, and chronic kidney disease. Anemia in a chronic disease related to acute or chronic immune activation, which includes elevated levels of cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6).4 Heart failure in ACHD follows a chronic course and patients with ACHD may have anemia resulting from cytokine activation.

In a retrospective cohort study, we investigated whether RDW is associated with cardiovascular mortality after adjustment for anemia, and we evaluated the relationships among anemia, IL-6, and RDW in patients with ACHD.

This study included 144 patients with ACHD who were hospitalized during the period 2005–2012 for long-term cardiac evaluation. We conducted follow-up for an 8-year period from 2005 to 2013. Patients with ACHD who received cardiac transplants and those who died from noncardiovascular causes or contracted immunological and neurogenic diseases were excluded from the study.

Clinical VariablesWe examined the patients’ clinical records during hospitalization for long-term cardiac evaluation and collected information related to baseline characteristics (age, sex, weight, height, body mass index [BMI], New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class, percutaneous saturation, cardiothoracic ratio, and medication at initial admission, including angiotensin-receptor blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and β-blockers), category of CHD, and clinical history (angina pectoris or myocardial infarction, hypertension, stroke or syncope, thrombus, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, hemoptysis, and arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, complete atrioventricular block, and atrial tachycardia/atrial flutter/atrial fibrillation; Table 1). Chronic kidney disease was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2.

| Overall (n=144) | RDW >15% (n=28) | RDW ≤15% (n=116) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 28 (22–36) | 31 (25–40) | 27 (21–36) | 0.072 |

| Male | 66 (45) | 13 (46) | 53 (45) | 0.554 |

| Weight (kg) | 54 (46–60) | 52 (47–57) | 55 (45–61) | 0.456 |

| Height (cm) | 161±9 | 160±7 | 161±9 | 0.711 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.3 (18.5–23.2) | 20.0 (18.4–22.0) | 20.6 (18.6–23.6) | 0.354 |

| NYHA class III/IV | 23 (16) | 9 (32) | 14 (12) | 0.014* |

| Percutaneous oxygen saturation (%) | 95 (88–98) | 86 (80–95) | 95 (92–98) | <0.001* |

| Cardiothoracic ratio (%) | 55 (50–62) | 58 (54–67) | 54 (49–61) | 0.037* |

| Medical therapy at initial admission | ||||

| ARBs | 18 (12) | 5 (17) | 13 (11) | 0.253 |

| ACEIs | 51 (35) | 10 (35) | 41 (35) | 0.568 |

| β-blockers | 59 (41) | 13 (46) | 46 (39) | 0.328 |

| Category of CHD | ||||

| Mixed type | 31 (21) | 6 (21) | 25 (21) | 0.606 |

| Pulmonary right ventricle type | 15 (10) | 3 (10) | 12 (10) | 0.591 |

| Systemic right ventricle type | 21 (14) | 4 (14) | 17 (14) | 0.614 |

| Unrepaired group | 2 (1) | 1 (3) | 1 (0) | 0.352 |

| Glenn shunt | 4 (2) | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.583 |

| Fontan | 71 (49) | 13 (46) | 58 (50) | 0.449 |

| Clinical history | ||||

| Angina or myocardial infarction | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.520 |

| Hypertension | 6 (4) | 1 (3) | 5 (4) | 0.669 |

| Stroke or syncope | 13 (9) | 3 (10) | 10 (8) | 0.488 |

| Thrombus | 18 (12) | 5 (17) | 13 (11) | 0.253 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (2) | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.583 |

| Chronic kidney disease‡ | 17 (11) | 6 (21) | 11 (9) | 0.081 |

| Hemoptysis | 7 (4) | 4 (14) | 3 (2) | 0.027* |

| Arrhythmia | ||||

| VT | 12 (8) | 2 (7) | 10 (8) | 0.576 |

| SVT | 11 (7) | 1 (3) | 10 (8) | 0.328 |

| CAVB | 9 (6) | 1 (3) | 8 (6) | 0.447 |

| SSS | 6 (4) | 1 (3) | 5 (4) | 0.669 |

| AT/AF/AFl | 68 (47) | 13 (46) | 55 (47) | 0.547 |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| Anemia† | 50 (34) | 22 (78) | 28 (24) | <0.001* |

| Hematocrit (%) | 45.3 (41.2–49.9) | 45.4 (38.7–54.9) | 45.3 (41.9–49.1) | 0.846 |

| MCV (fl) | 91.6 (88.3–94.0) | 85.6 (78.5–90.0) | 92.1 (89.4–94.6) | <0.001* |

| RDW (%) | 13.7 (13.0–14.7) | 16.2 (15.4–18.1) | 13.3 (12.9–14.0) | <0.001* |

All data are shown as median (IQR) and mean±(standard deviations) or number (%) as indicated. *P<0.05, high RDW group vs. low RDW group. †Anemia defined according to the WHO criteria: women <12, men <13, or when hemoglobin was below the predicted hemoglobin calculated by the formula: predicted hemoglobin=61−(O2 saturation/2) for cyanotic patients with adult congenital heart disease. ‡Chronic kidney disease defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; AFl, atrial flutter; ARBs, angiotensin-receptor blockers; AT, atrial tachycardia; BMI, body mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CAVB, complete atrioventricular block; CHD, congenital heart disease; IQR, interquartile range; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RDW, red cell distribution width; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

The samples were acquired in the course of routine examination at first hospitalization. The RDW coefficient of variance (%) was determined using the Sysmex XE-5000 analyzer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) within a few hours of collection. The local abnormal RDW cutoff value (>15.0%) was used. Anemia without cyanosis (ie, not decreased percutaneous oxygen saturation (≥95%)) was defined using the World Health Organization criteria of a hemoglobin level <12 g/dl in women and 13 g/dl in men.8 Anemia with cyanosis (ie, decreased percutaneous oxygen saturation (<95%)) was defined according to values calculated using the formula: predicted hemoglobin=61–(O2 saturation/2).9,10

Laboratory MeasurementsBiomarkers were measured at first hospitalization using biochemical tests. Serum samples were drawn by venipuncture after ≥30 min of supine rest, immediately placed on ice, and centrifuged within 30 min. Plasma samples were stored at −80℃ until analysis. IL-6 levels were measured using a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (Human IL-6 CLEIA kit; Fujirebio).

Study ProtocolThis was a single-center, retrospective cohort study. The endpoint was cardiovascular death after hospitalization for worsening heart failure. Approval was obtained from the Tokyo Women’s Medical University Hospital institutional review board. All patients or their parents were informed of the significance and risks of the study and gave their consent according to the rules of the hospital.

Statistical AnalysisThe numbers (percentage), means (standard deviations [SD]), and medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]) of the baseline characteristics in Table 1 and 2 were analyzed using the chi-square test (Fisher’s exact test), t-test, or Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate. The relationships among RDW, percutaneous oxygen saturation, IL-6 were examined with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The distribution of the original data was tested separately using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Hazard ratios (HR) for hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and RDW were analyzed using standardized HR, which were related to 1 SD changes in the levels of RDW. The HR of variables that differed significantly between the higher and lower RDW groups, which we assumed to be confounders between RDW and mortality, were analyzed in univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses with forward stepwise selection. The area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was analyzed to assess significant variables as potential predictors of cardiovascular mortality. The survivor function for freedom from mortality was computed from the Cox proportional regression model. The SPSS version 19 statistical software package (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses. P<0.05 was considered significant.

| Anemia without cyanosis (n=6) |

Anemia with cyanosis (n=16) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 30 (25–35) | 35 (26–43) | 0.357 |

| Male | 2 (33) | 8 (50) | 0.646 |

| Weight (kg) | 53 (44–57) | 55 (52–62) | 0.319 |

| Height (cm) | 156 (153–163) | 162 (158–171) | 0.090 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21 (18–23) | 20 (19–22) | 0.883 |

| NYHA class III/IV | 1 (17) | 6 (38) | 0.616 |

| Percutaneous oxygen saturation (%) | 98 (97–98) | 82 (79–91) | <0.001* |

| Cardiothoracic ratio (%) | 58 (55–64) | 59 (55–73) | 0.506 |

| Medical therapy at initial admission | |||

| ARBs | 1 (17) | 4 (25) | 1.000 |

| ACEIs | 3 (50) | 5 (31) | 0.624 |

| β-blockers | 1 (17) | 8 (50) | 0.333 |

| Category of CHD | |||

| Mixed type | 2 (33) | 2 (13) | 0.292 |

| Pulmonary right ventricle type | 1 (17) | 1 (6) | 0.481 |

| Systemic right ventricle type | 3 (50) | 1 (6) | 0.046* |

| Unrepaired group | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1.000 |

| Glenn shunt | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1.000 |

| Fontan | 0 (0) | 10 (63) | 0.015* |

| Clinical history | |||

| Angina or myocardial infarction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Hypertension | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0.273 |

| Stroke or syncope | 0 (0) | 3 (19) | 0.532 |

| Thrombus | 0 (0) | 5 (31) | 0.266 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1.000 |

| Chronic kidney disease† | 1 (25) | 4 (40) | 1.000 |

| Hemoptysis | 0 (0) | 3 (18) | 0.532 |

| Arrhythmia | |||

| VT | 1 (17) | 1 (6) | 0.481 |

| SVT | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| CAVB | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1.000 |

| SSS | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1.000 |

| AT/AF/AFl | 1 (17) | 10 (63) | 0.149 |

| Laboratory results | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.7 (10.5–12.1) | 15.1 (13.5–16.8) | 0.005* |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36.3 (34.9–37.7) | 47.8 (42.0–52.3) | 0.002* |

| MCV (fl) | 76.5 (72.3–86.0) | 86.5 (81.2–90.4) | 0.042* |

| RDW (%) | 15.3 (15.1–16.9) | 16.2 (15.5–17.6) | 0.112 |

All data are shown as median (IQR) or number (%) as indicated.

*P<0.05, anemia without cyanosis group vs. anemia with cyanosis group. †Chronic kidney disease defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. NA, not available. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

During a mean follow-up of 4.8±2.9 years, 21 (15%) patients died from cardiovascular causes. The overall 5-year survival rate, estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis, was 86.0%; 10 (7%) patients were lost to follow-up. The median age (IQR) of all 144 patients with ACHD was 28 (22–36) years and 84% were in NYHA class I/II. ACHD was divided into the following 6 categories, as described in a previous study: mixed type; pulmonary right ventricle type, such as an atrial septal defect with right ventricle volume overload; systemic right ventricle type, such as a corrected transposition of the great artery (TGA) and d-transposition of TGA with atrial switch operation; unrepaired type; Glenn shunt type; and Fontan type (Table 1).11 There were no significant differences between the higher RDW group and lower RDW group in the prevalence of these ACHD categories.

Characteristics Stratified by RDWAccording to the baseline characteristics listed in Table 1, percutaneous oxygen saturation was significantly lower among patients in the higher RDW group (n=28) than among those in the lower RDW group (n=116). Patients’ cardiothoracic ratios were significantly higher in the higher RDW group than in the lower RDW group. The higher RDW group had a significantly higher prevalence of NYHA class III/IV cases and patients with a history of hemoptysis than did the lower RDW group. Regarding the laboratory tests, the higher RDW group had anemia and lower MCV levels when compared with the lower RDW group.

Comparison of Anemia With Cyanosis and Anemia Without Cyanosis in ACHD Patients With Higher RDWComparison between 6 cyanotic and 16 non-cyanotic patients in the anemia with higher RDW group (Table 2), revealed that the prevalence of systemic right ventricle type was significantly higher in the non-cyanotic group than in the cyanotic group. Prevalence of Fontan type and levels of hemoglobin, hematocrit, and MCV were significantly higher in the cyanotic group than in the non-cyanotic group.

Correlations Among RDW, Percutaneous Oxygen Saturation, and IL-6 LevelsRDW had a positive correlation with IL-6 (r=0.394, P<0.001) and significant negative correlation with percutaneous oxygen saturation (r=−0.510, P<0.001).

Cardiovascular MortalityAccording to RDW Percutaneous oxygen saturation, together with a history of hemoptysis, anemia, MCV, or RDW, was chosen as a significant variable from Table 1. The results of Cox proportional regression analysis are shown in Table 3. Percutaneous oxygen saturation, anemia, MCV, and RDW were significantly associated with cardiovascular mortality in the univariate analysis. Elevated RDW, MCV, and anemia were significantly associated with mortality in the multivariate analyses. Analysis of the anemia-adjusted cardiovascular mortality in patients with ACHD showed that the adjusted standardized HR of RDW (HR: 1.912; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.369–2.670 per 1 SD increase; P<0.001) was greater than the unadjusted HR (HR: 1.570; 95% CI: 1.208–2.040 per 1 SD increase; P=0.001). In the multivariate analysis, the statistical contribution of RDW and MCV to the prevalence of cardiovascular death, as analyzed using the chi-square test, was greater than that of anemia.

| Independent variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis (forward stepwise selection) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | Chi-square value | P value | |

| Percutaneous oxygen saturation (%) | 0.947 (0.899–0.997) | 0.039 | |||

| History of hemoptysis | 1.546 (0.358–6.669) | 0.559 | |||

| Anemia | 3.878 (1.564–9.612) | 0.003 | 2.822 (1.100–7.240) | 4 | 0.031 |

| MCV per 1 SD | 2.240 (1.113–4.508) | 0.024 | 3.141 (1.767–5.583) | 15 | <0.001 |

| RDW per 1 SD | 1.570 (1.208–2.040) | 0.001 | 1.912 (1.369–2.670) | 14 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SD, standard deviation. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

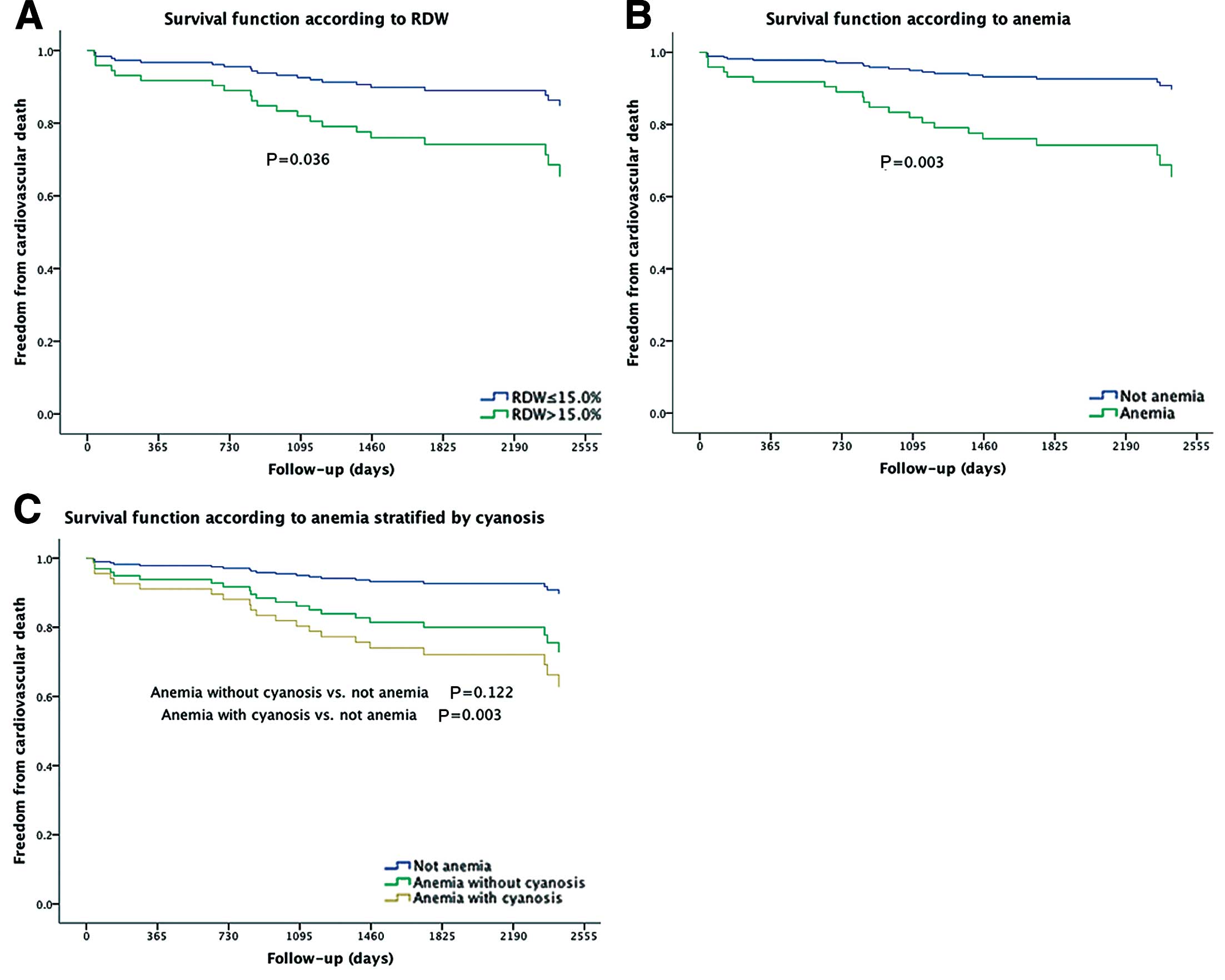

According to Anemia Stratified by Cyanosis Comparisons among the non-anemia group, anemia with cyanosis group, and anemia without cyanosis group in the univariate analysis, revealed that the anemia with cyanosis group was significantly associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR: 4.266; 95% CI: 1.653–11.008, P=0.003), compared with the non-anemic group, despite no significant difference between the non-anemic group and anemia without cyanosis group (HR: 2.907; 95% CI: 0.751–11.254, P=0.122) (Figure 1C).

Survivor functions of red cell distribution width (RDW, A), anemia (B), and anemia with or without cyanosis (C) for freedom from cardiovascular death in patients with congenital heart disease.

The laboratory variables yielded the following results: RDW: AUC, 0.70, 95% CI, 0.59–0.82, P=0.002; anemia: AUC, 0.68, 95% CI, 0.56–0.81, P=0.006; and MCV as a dichotomous variable (comparison between high MCV group [≥80fl] and low MCV group [<80fl]): AUC 0.52, 95% CI, 0.38–0.66, P=0.734. Survivor functions for freedom from cardiovascular death showed significant differences between the higher and lower RDW groups, and between patients with and without anemia (Figures 1A,B), whereas these functions showed no significant difference between the lower (<80fl) and higher (≥80fl) MCV groups (P=0.517).

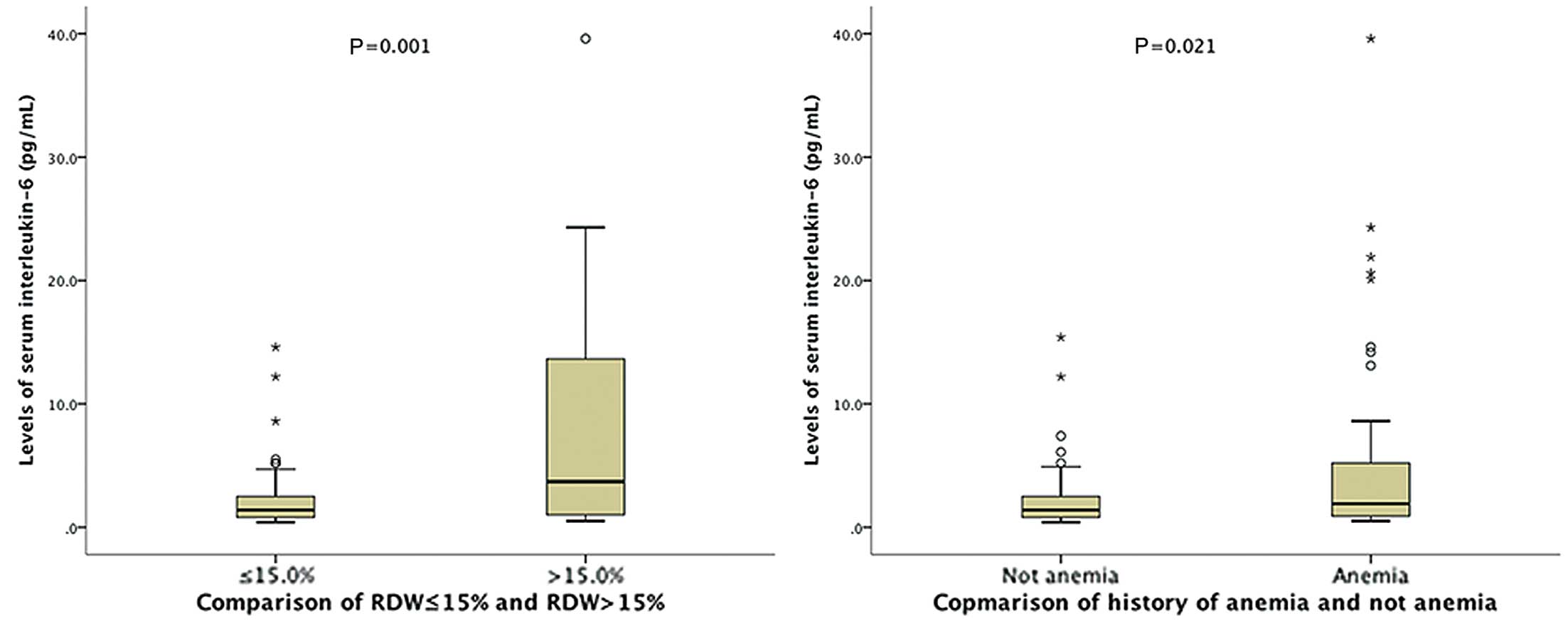

Relationship Among RDW, Anemia, and IL-6 LevelsAs shown in Figure 2, the higher RDW group (>15%) had significantly greater serum IL-6 levels when compared with the lower RDW group (median [IQR], 3.7 [0.9–13.9] pg/ml vs. 1.4 [0.8–2.5] pg/ml, P=0.001). Patients with a history of anemia had significantly higher serum IL-6 levels than did patients without (1.8 [0.9–5.2] pg/ml vs. 1.4 [0.8–2.5] pg/ml, P=0.021).

(Left) Interleukin-6 levels (median and interquartile range) in patients with red cell distribution width (RDW) >15% and <15% were 3.7 (0.9–13.9) pg/ml and 1.4 (0.8–2.5) pg/ml, respectively (P=0.001; Mann-Whitney U-test). (Right) Interleukin-6 levels in patients with and without a history of anemia were 1.8 (0.9–5.2) pg/ml and 1.4 (0.8–2.5) pg/ml, respectively (P=0.021).

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that elevated RDW could be used as an index of anemia-adjusted cardiovascular mortality in patients with ACHD. We also demonstrated that patients with a higher RDW level had significantly increased serum IL-6 levels.

RDW is a quantified representation of the variability of the size of circulating erythrocytes, which is calculated as the standard deviation of the distribution of red blood cell size divided by the MCV. Therefore, higher RDW levels reflect greater heterogeneity in the size of erythrocytes (anisocytosis). RDW is routinely tested in the clinical setting as part of the automated complete blood count, and the values become elevated under conditions of increased red blood cell destruction or compromised red blood cell production. Elevated RDW is thought to represent bone marrow dysfunction, nutritional deficiency, or chronic inflammation, which are commonly seen in patients with chronic heart failure.

A previous study in adults showed that RDW was an independent and strong predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality.7,12–17 A meta-analysis of 7 studies of RDW revealed that it was associated with multiple causes of death in older adults and was a strong predictor of mortality in this population, after adjustment for age, sex, race, education, smoking status, BMI, estimated glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin concentration, MCV, and serum albumin.5 In addition, an elevated RDW was associated with aging and the progression of various types of disorders.

Previous studies showed that RDW is a predictor of anemia in patients with heart failure.2,18,19 Further, a previous meta-analysis found that RDW was more strongly associated with all-cause mortality in older adults without anemia than in those with anemia.5 Therefore, anemia may be a confounding variable in the relationship between RDW and cardiovascular mortality. An earlier cohort study of older patients found that RDW adjusted for hemoglobin concentration was a significant predictor of cardiovascular mortality.20 Our cohort study of ACHD also revealed that RDW was associated with anemia-adjusted cardiovascular mortality.

The relationship between RDW and mortality in patients with ACHD has not been fully evaluated.21 Aung et al revealed that the RDW was a strong predictor of cardiac mortality in patients who underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation, but their study did not describe cardiovascular mortality after adjusting for anemia.22 The present report is the first to show that, after adjustment for anemia, RDW is an independent and strong predictor of cardiovascular mortality in ACHD patients.

Previous studies showed that an increased RDW in patients with cyanotic CHD and Fontan circulation was significantly associated with iron deficiency status accompanied by polycythemia.3,23–27 A previous study also reported that patients with cyanotic ACHD had a high prevalence (60%) of anemia, with increased RDW and polycythemia.9 In our study of ACHD patients, including cyanotic and acyanotic ACHD, we found similar results; namely, that low-MCV anemia was significantly more prevalent in the higher RDW group than in the lower RDW group. Additionally, this is a rare report of a cohort study of ACHD in which anemic patients with cyanosis in the higher RDW group are significantly associated with cardiovascular mortality risk. Although the cause of anemia in previous studies was explained by the iron-deficient status in cyanotic ACHD patients, iron deficiency may not be the sole cause of anemia. Our study confirmed that patients with a higher RDW had significantly increased IL-6 levels compared with patients with a lower RDW. A previous multicenter cohort study evaluated the relationship between RDW and the expression of cytokines, including IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1 β, and endothelin-1, in older adults, and found that only an elevated IL-6 level was associated significantly with an increased RDW.28

A great deal of evidence has accumulated to show that heart failure in patients with ACHD is characterized by a chronic clinical course.29,30 Anemia in chronic disease may be associated with increased IL-6 levels and can be explained by impaired iron metabolism.4 Weiss et al reported that anemia in chronic disease is the progressive impairment of iron homeostasis, with increased iron retention within cells of the reticuloendothelial system following the phagocytosis of senescent erythrocytes.4 Regarding inflammation and cytokines, IL-6 helps to stimulate the hepatic expression of hepcidin, which is produced in the liver and inhibits the absorption of iron from the duodenum28 Moreover, Allen et al found that patients with iron-deficiency anemia in chronic disease had increased numbers of microcytes and tended to exhibit more severe disease.28 Therefore, anemia in chronic disease tends to be complicated by increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines.4 Inflammation, including cytokines such as IL-1, 6, 18, and tumor necrosis factor-α, plays an important role in the etiology and progression of heart failure in patients with acquired and congenital heart diseases. Biomarkers of inflammation are strongly associated with left ventricular dysfunction, pulmonary edema, cardiomyopathy, decreased skeletal muscle blood flow, endothelial dysfunction, anorexia, and cachexia.31 Our results may have revealed a mechanism of anemia in patients with ACHD that results not only from iron-deficiency anemia, but also from anemia of chronic disease, given that the patients with anemia had significantly increased IL-6 levels. IL-6 as a proinflammatory cytokine may inhibit erythropoietin-induced erythrocyte maturation, which is reflected in part by an elevated RDW.

Our study had some limitations. As it was a retrospective study, with a small sample size, the results need to be verified in a prospective study of a larger cohort.

The findings of this study lead to the conclusion that RDW, an inexpensive clinical test, is nevertheless a powerful diagnostic predictor of cardiovascular mortality. Additional research is necessary to determine whether RDW is a useful parameter for risk assessment in patients with ACHD.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.