2018 Volume 82 Issue 11 Pages 2767-2775

2018 Volume 82 Issue 11 Pages 2767-2775

Background: The number of surgical aortic valve replacements using bioprosthetic valves is increasing, and newer bioprosthetic valves may offer clinical advantages in Japanese patients, who generally require smaller replacement valves than Western patients. In this study we retrospectively evaluated the Trifecta and Magna valves to compare clinical outcomes and hemodynamics in a group of Japanese patients.

Methods and Results: Data were retrospectively collected for 103 patients receiving a Trifecta valve and 356 patients receiving a Magna valve between June 2008 and 2017. Adverse events, outcomes, and valve hemodynamics were evaluated. There were no significant differences in early or late outcomes between the Trifecta and Magna groups. In the early postoperative period, mean (±SD) pressure gradient (9.0±3.1 vs. 13.8±4.8 mmHg; P<0.01) and effective orifice area (1.68±0.46 vs. 1.46±0.40 m2; P<0.01) were significantly better for Trifecta, but the differences decreased over time. In particular, the interaction between time and valve type (Trifecta or Magna) was significantly different for mean pressure gradient between the 2 groups (P<0.01). Left ventricular mass regressed substantially in both groups, with no significant difference between them. There were no significant differences for severe patient-prosthesis mismatch.

Conclusions: Postoperative outcomes were similar for both valves. An early hemodynamic advantage for the Trifecta valve lasted to approximately 1 year postoperatively but did not persist.

The number of surgical aortic valve replacements (AVRs) using a bioprosthesis is increasing according to the annual surveys of thoracic surgery by the Japanese association for thoracic surgery (http://www.jpats.org/modules/investigation/index.php?content_id=7), which states that bioprostheses are used in three-quarters of all AVR procedures. In addition, the age limit for implantation of an aortic bioprosthesis is continuously being shifting down,1 with bioprostheses used for AVR in 60% of sexagenarian patients and 90% of septuagenarian or octogenarian patients.2 This may be related to the enhanced durability of new-generation bioprostheses, improved outcomes of redo valve replacement surgery, or the development of valve-in-valve (ViV) transcatheter aortic valve implantation.3

The new-generation bioprostheses, including the Trifecta (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) or the Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Magna or Magna Ease (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA), reportedly have design advantages in terms of their large effective orifice area (EOA) and low pressure gradients, as well as in terms of the materials used, including anticalcification treatment, which potentially results in good hemodynamics and avoids patient-prosthesis mismatch.4 In addition, the new-generation bioprostheses have long-term durability. The valve leaflets of both the Trifecta and Magna prostheses are generated by glutaraldehyde-treated bovine pericardium but differ in their preparation and design. These fundamental differences may result in clinically prominent differences in their hemodynamics that should be considered particularly for Japanese patients, who have a small aortic annulus relative to their body size and require a smaller prosthesis than Western patients.5 Therefore, the aims of this study were to review clinical outcomes at the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center after AVR using either valve and to compare the hemodynamic performance of each valve.

This study was an observational single-center cohort study. The institutional surgical database contained a consecutive series of 876 patients who underwent surgical AVR with a prosthetic valve at the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center between June 2008 and 2017. Mechanical prosthetic valves were implanted in 162 patients (18.5%), whereas the remaining 714 patients (81.5%) underwent AVR with a stented bioprosthetic valve, such as the Trifecta (n=110 patients; 12.6%), Magna (n=374 patients; 42.7%), Mosaic (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA; n=185 patients; 21.1%), or Crown/Mitroflow (Sorin, Milan, Italy; n=45 patients; 5.1%) valves. Patients who underwent concomitant surgical procedures that potentially affected the clinical outcome and valve hemodynamics, such as septal myectomy or root enlargement, were excluded from this study. In addition, redo cases were excluded from the study because the aortic annulus, which is the critical structure in determining the hemodynamics of the prosthetic valve, is often deformed by the scar tissue and/or possibly by the surgical manipulation. Consequently, 103 patients with a Trifecta valve and 356 patients with Magna valve were evaluated in this study. Follow-up was completed for 102 patients (99.0%) with a Trifecta valve and 340 patients (95.5%) with a Magna valve.

Data were collected by reviewing patients’ medical charts, surgical reports, and referral letters, supplemented by telephone interviews for patients under the care of distant physicians. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) were classified according to the standard definitions.6 Events were classified as occurring early (within 30 days of implantation) or late (>31 days after implantation). Data collection was performed between January and February 2018. All patients gave written informed consent for surgery and the use of their data for diagnostic and research purposes prior to the surgery. The Institutional Review Board of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center waived ethics compliance for this retrospective study.

Patient Background and CharacteristicsInformation regarding patient background and characteristics were retrieved from the medical charts. Prosthesis type and size were determined intraoperatively by individual surgeons as the best-matched prosthesis for each patient. In the Magna group, 134 patients (37.6%) received a Magna valve and 222 patients (62.4%) received the Magna Ease valve, which was introduced in the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in 2011; the Trifecta valve was introduced in 2012. Patients in both groups underwent clinical and echocardiographic assessment preoperatively, on hospital discharge, 1 year postoperatively, and during follow-up (range 2–10 years).

Surgical Indications, Procedure, and Postoperative CareAlthough the surgical indications for AVR were determined by the institutional heart team essentially according to recommended guidelines,7,8 the prosthesis type was determined by the patient and their surgeon to select the best-matched type and size. As a result, there was no significant difference in patient background or characteristics between the Trifecta and Magna groups, with the exception of patient age at surgery (Table 1). The age difference may be secondary to the transcatheter ViV procedure, in which implantation is reportedly easier for the Magna than Trifecta valve.9 Surgical AVR was performed via a median sternotomy in all patients in the Trifecta group and in 343 patients (96.3%) in the Magna group, whereas a minimally invasive approach, such as an upper partial sternotomy or right minithoracotomy, was used in 13 patients in the Magna group (Table 2). Prosthetic valve size or concomitant surgical procedures were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Postoperatively, aspirin 100 mg/day was given until the latest follow-up, whereas warfarin was given to a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5–2.5 for 3 months unless patients required anticoagulant therapy, such as those with atrial fibrillation. Following hospital discharge, patients were reassessed in the outpatient clinic or by a distant physician every 3 months until the latest follow-up.

| Trifecta (n=103) |

Magna (n=356) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.9±8.3 | 69.0±9.9 | <0.01 |

| Sex (M/F) | 49/54 | 213/143 | 0.212 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.57±0.19 | 1.60±0.19 | 0.206 |

| Valve disease | |||

| Aortic stenosis | 63 (61.8) | 217 (61.0) | 0.909 |

| Aortic insufficiency | 18 (17.6) | 58 (16.3) | 0.763 |

| Mixed | 12 (11.8) | 32 (9.0) | 0.446 |

| Valve pathology | |||

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 23 (23.7) | 103 (30.7) | 0.206 |

| Degenerative/rheumatic | 52 (53.6) | 179 (53.1) | 1.000 |

| Infective endocarditis | 5 (4.9) | 10 (2.8) | 0.341 |

| Cardiac comorbidity | |||

| Coronary stenosis | 24 (23.5) | 68 (19.1) | 0.329 |

| History of PCI | 4 (3.9) | 22 (6.2) | 0.474 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 20 (19.4) | 73 (20.5) | 0.890 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 11 (10.7) | 33 (9.3) | 0.704 |

| Non-cardiac comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 80 (77.7) | 272 (76.4) | 0.895 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 50 (48.5) | 172 (48.3) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 26 (25.2) | 61 (17.1) | 0.086 |

| Diabetes with insulin treatment | 2 (1.9) | 6 (1.7) | 1.00 |

| COPD | 30 (29.1) | 76 (21.3) | 0.111 |

| Smoking | 33 (32.0) | 124 (34.8) | 0.638 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7±0.6 | 5.6±0.7 | 0.09 |

| Prior stroke | 13 (12.6) | 26 (7.3) | 0.107 |

| Carotid stenosis | 5 (4.9) | 11 (3.1) | 0.37 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4 (3.9) | 13 (3.7) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (8.7) | 26 (7.3) | 0.673 |

| Dialysis | 1 (1.0) | 7 (2.0) | 0.69 |

| NYHA class | |||

| I | 2 (1.9) | 13 (3.7) | 0.538 |

| II | 83 (80.6) | 307 (86.2) | 0.161 |

| III | 15 (14.5) | 32 (9.0) | 0.138 |

| IV | 3 (2.9) | 4 (1.1) | 0.191 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 281±531 | 263±530 | 0.767 |

| Preoperative echocardiography | |||

| LVDd (mm) | 51.1±8.8 | 53.2±10.9 | 0.079 |

| LVDs (mm) | 34.1±10.7 | 35.8±11.3 | 0.162 |

| LVEF (%) | 57.3±15.3 | 56.0±13.1 | 0.406 |

| LVMI (g/m2) | 128.9±38.9 | 137.7±47.1 | 0.085 |

| Preoperative AVA (cm2) | 0.79±0.29 | 0.76±0.23 | 0.299 |

| Preoperative AVAi (cm2) | 0.50±0.19 | 0.49±0.15 | 0.482 |

| Preoperative MPG (mmHg) | 52.0±22.4 | 48.7±17.9 | 0.183 |

| Risk score (%) | |||

| EuroSCORE II | 2.9±2.4 | 3.3±4.3 | 0.413 |

Data are presented as mean±SD or n (%). AVA, aortic valve area; AVAi, aortic valve area index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; LVDd, left ventricular internal diameter in diastole; LVDs, left ventricular internal diameter in systole; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; MPG, mean pressure gradient; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

| Trifecta (n=103) |

Magna (n=356) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | |||

| Isolated AVR | 49 (48.0) | 176 (49.4) | 0.823 |

| MICS procedure | 0 | 13 (3.7) | 1.000 |

| Concomitant procedure | |||

| Ascending aorta surgery | 13 (12.7) | 33 (9.3) | 0.349 |

| Mitral valve surgery | 15 (14.7) | 58 (16.3) | 0.761 |

| Tricuspid valve repair | 9 (8.8) | 27 (7.6) | 0.679 |

| CABG | 23 (22.5) | 71 (19.9) | 0.579 |

| Maze procedure | 13 (12.7) | 43 (12.1) | 0.864 |

| Operation time (min) | 312±101 | 304±84 | 0.395 |

| ACC time (min) | 104±36 | 101±36 | 0.339 |

| CPB time (min) | 147±46 | 147±45 | 0.839 |

| Prosthesis size (mm) | |||

| 19 | 36 (35.0) | 92 (25.8) | 0.081 |

| 21 | 24 (23.3) | 112 (31.5) | 0.113 |

| 23 | 35 (34.0) | 92 (25.8) | 0.106 |

| 25 | 8 (7.8) | 39 (11.0) | 0.460 |

| 27 | 0 | 21 (5.9) | – |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%). ACC, aortic cross-clamp time; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MICS, minimally invasive cardiac surgery.

All patients underwent the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center’s standard 2-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography preoperatively, and 5–7 days after AVR; however, 82 patients (79.6%) in the Trifecta group and 251 patients (70.5%) in the Magna group underwent echocardiography 1-year after AVR. In addition, 58 patients (56.3%) in the Trifecta group and 181 patients (50.8%) in the Magna group underwent echocardiography at a mean interval from surgery of 35 months (range 30–40.5 months) and 48 months (range 31.5–71.0 months), respectively.

Standard parameters were measured based on the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography.10 Briefly, Doppler flow data were acquired from the left ventricular outflow tract just proximal to the prosthesis sewing ring. The modified Bernoulli equation was used to calculate peak and mean pressure gradient (MPG) across the prosthetic valve. EOA was calculated using a continuity equation on echo Doppler assessments. Patient-prosthesis mismatch, which was calculated as indexed EOA (iEOA)/body surface area, was classified as not clinically significant (iEOA >1 cm2/m2), mild (iEOA 0.85–1 cm2/m2), moderate (iEOA 0.65–0.85 cm2/m2), or severe (iEOA <0.65 cm2/m2).11 Left ventricular mass (LVM; g) was calculated using the following formula and indexed to body surface area (LMVi):

LVM (g)=0.8 (1.04 ([LVDd+PWTd+ISTd]3–LVDd3))+0.6

where LVDd is left ventricular internal diameter in diastole, PWTd is posterior wall thickness in diastole, and ISTd is interventricular septum thickness in diastole.

The effect of LVMi regression was evaluated by comparing preoperative values with those in each postoperative period (at discharge, 1 year postoperatively, and follow-up). The measured parameters were recorded in the official echocardiographic report, which was retrieved as data for this study.

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are presented as the mean±SD, whereas categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Survival and event-free survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Hemodynamic primary endpoints were interactions between time points (discharge, 1 year postoperatively, and at each follow-up) and valve type (Trifecta vs. Magna) for MPG, EOA, and LVMi after adjusting for the following baseline characteristics: age, sex, body surface area, valve size, history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, carotid artery stenosis, prior stroke, peripheral arterial disease, smoking habit, preoperative New York Heart Association class,12 preoperative European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE),13 preoperative ejection fraction, preoperative stroke volume, type of valve disease, tricuspid valve, bicuspid valve, and etiology of the valve disease. Linear model estimation using ordinary least squares and the Huber-White method was used to adjust the variance–covariance matrix of a fit from least squares to correct for heteroscedasticity and for correlated responses from patients. A multivariate covariance analysis model was constructed to further compare the primary study endpoints (MPG, EOA, and LVMi) at the 1-year follow-up. The second endpoint was analysis of the overall survival and freedom from MACCE, using the preoperative variables for the regression analysis. A validated statistical linear mixed model was used to analyze the effect of each prosthetic valve function (the hemodynamic parameters). Continuous variables without repeated measures were tested using an unpaired t-test, whereas continuous variables with repeated measures were tested using a paired t-test; ordinal variables were tested using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were tested using the Chi-squared test, and 2-sided statistics were performed with significance set at a level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using R 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Either Trifecta (n=103) or Magna (n=356) valves were used for AVR in patients in this study. One patient died in each group from thromboembolic events within 30 days postoperatively (Table 3). Cerebrovascular accidents occurred in 2 patients (0.6%) in the Magna group, whereas new permanent pacemaker implantation was performed for complete atrioventricular block in 3 patients (0.8%) in the Magna group. Perioperative myocardial infarction occurred in 1 patient in the Magna group. In this patient, thromboembolic occlusion of the left anterior descending artery occurred 12 h after the end of surgery, which was successfully treated by transcatheter thrombectomy. As a result, there was no significant difference in the 30-day outcome between the 2 groups.

| Trifecta (n=103) |

Magna (n=356) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up period (months) | 31.0 [15.0–42.0] | 36.0 [15.0–64.0] | <0.01 |

| Follow-up rate | 102 (99.0) | 340 (95.5) | 0.137 |

| Early MACCE | 2 (1.9) | 7 (2.0) | 1.00 |

| 30-day mortality | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0.399 |

| Cerebrovascular accidents (stroke) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1.00 |

| Permanent pacemaker implant | 0 | 3 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| Heart failure | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0.224 |

| Perioperative myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Late MACCE | 14 (13.6) | 60 (16.9) | 0.543 |

| Late mortality | 4 (3.9) | 17 (4.8) | 1.00 |

| Cardiac cause | 0 | 4 (1.1) | 0.579 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 0 | 3 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| Pneumonia | 2 (1.9) | 4 (1.1) | 0.62 |

| Cancer | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0.399 |

| Septic shock | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Unknown cause | 1 (0.9) | 4 (1.1) | 1.00 |

| Cerebrovascular accidents (stroke) | 2 (1.9) | 13 (3.7) | 0.538 |

| Permanent pacemaker implant | 0 | 15 (4.2) | 0.028 |

| Heart failure | 4 (3.9) | 9 (2.5) | 0.5 |

| Acute aortic dissection | 0 | 3 (0.8) | 1.00 |

| Reintervention | 2 (1.9) | 8 (2.2) | 1.00 |

| SVD | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| PVE | 2 (1.9) | 6 (1.7) | 1.00 |

| PVL | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 |

| Other operation | 2 (1.9) | 2 (0.6) | 1.00 |

Data are presented as the median [interquartile range] or n (%). MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis; PVL, paravalvular leak; SVD, structural valve deterioration.

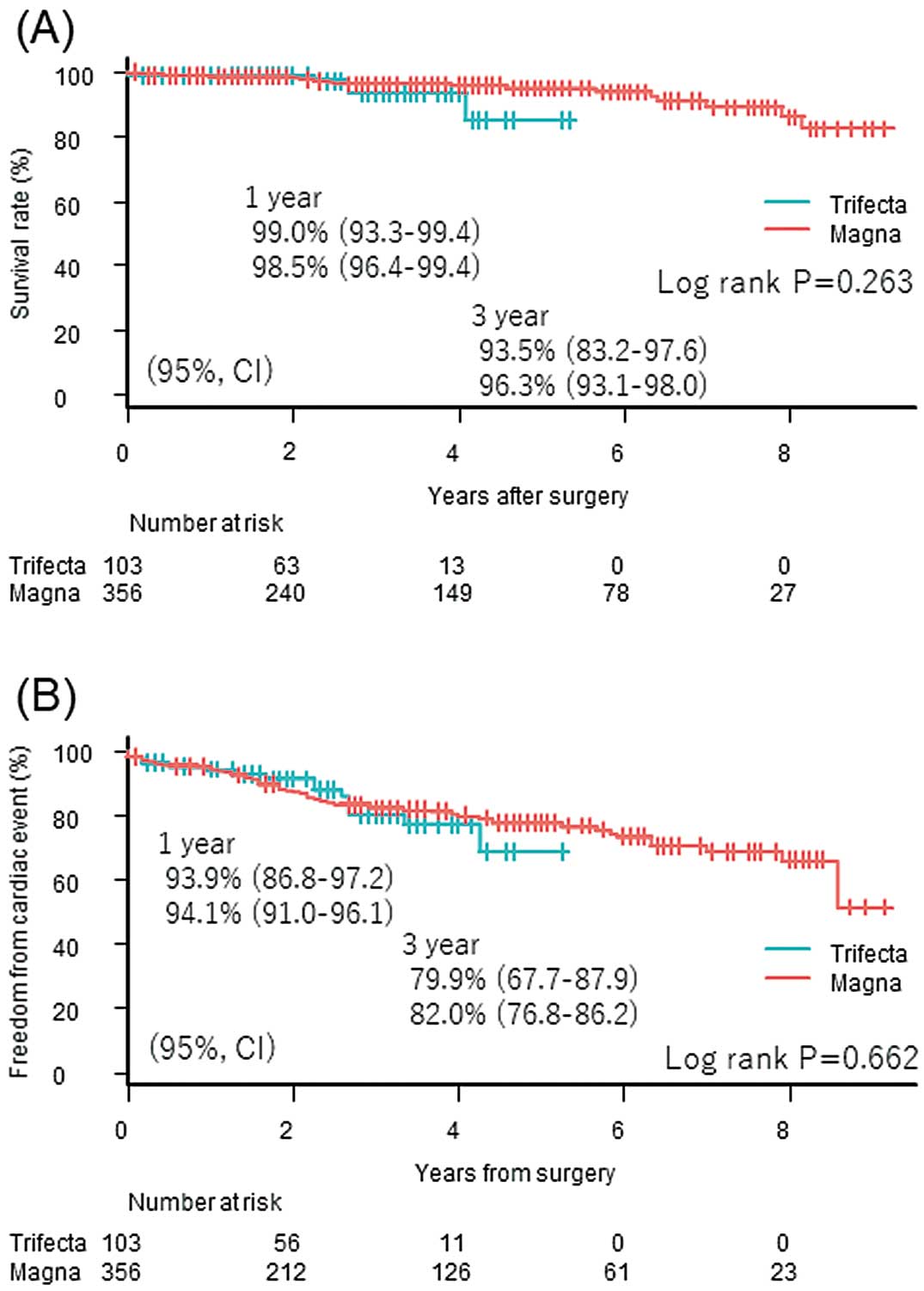

Patient follow-up was completed at the end of the study in 102 patients (99.0%) in the Trifecta group and in 340 patients (95.5%) in the Magna group (P=0.09), with a mean follow-up of 31.0 months (range 15.0–42.0 months) and 36.0 months (range 15.0–64.0 months), respectively (P<0.01). This significant difference is explained by the fact that the Magna valve was market released prior to the Trifecta valve. As a result, there were 4 deaths (3.9%) in the Trifecta group and 17 deaths (4.8%) in the Magna group by the end of the study. Actuarial survival in the Trifecta group was 99.0% at 1 year and 93.5% at 3 years, whereas in the Magna group it was 98.5% at 1 year and 96.3% at 3 years (log-rank, P=0.263; Figure 1A).

Long-term (A) survival and (B) freedom from major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events after aortic valve replacement with the Trifecta and Magna valves assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test.

Long-term MACCE included cerebrovascular accidents in 2 patients (1.9%) in the Trifecta group and in 13 patients (3.7%) in the Magna group. A permanent pacemaker was implanted after discharge in 15 patients in the Magna group only. Prosthetic valve endocarditis was diagnosed in 2 patients (1.9%) in the Trifecta group and in 6 patients (1.7%) in the Magna group. One patient in the Magna group experienced structural valve deterioration. As a result, freedom from MACCE in the Trifecta group was 93.9% at 1 year and 79.9% at 3 years, whereas in the Magna group it was 94.1% at 1 year and 82.0% at 3 years (log rank, P=0.662; Figure 1B). There was no significant difference in the incidence of MACCE between the 2 groups using logistic regression analysis (odds ratio [OR] 1.26; P=0.434) and proportional odds regression analysis (OR 1.27; P=0.413).

Difference in Valve Hemodynamics: Trifecta vs. MagnaAll patients underwent transthoracic echocardiography preoperatively, at discharge, and annually thereafter. Unadjusted average MPG for all valve sizes at discharge was significantly lower in the Trifecta than Magna group (9.0±3.1 vs. 13.8±4.8 mmHg, respectively; P<0.01). One year postoperatively, mean MPG for all sizes was significantly lower in the Trifecta than Magna group (10.9±3.8 vs. 12.7±5.3 mmHg, respectively; P<0.01), whereas there was no significant difference in MPG for 19-, 21-, and 25-mm valves at 1 year between the 2 groups. There was also no significant difference in MPG for all valve sizes between the 2 groups at the latest follow-up (11.1±4.1 vs. 12.4±4.6 mmHg in the Trifecta and Magna groups, respectively; P=0.062, Figure 2A). Interactions between time points (discharge, 1 year postoperatively, and at the latest follow-up) and valve type (Trifecta or Magna) for MPG were significantly different between the 2 groups (P<0.01), indicating that MPG was significantly lower in the Trifecta group soon after surgery, but thereafter the difference between groups was smaller (Figure 2B).

Transthoracic echocardiographic assessment of the mean pressure gradient (MPG) for each valve: (A) unadjusted (actual) data and (B) interaction between time points (at discharge, 1 year postoperatively, at follow-up) and valve type (Trifecta vs. Magna).

EOA showed a consistent trend regarding MPG (Figure 3A). Average EOA for all valve sizes at discharge was significantly larger in the Trifecta than Magna group (1.68±0.46 vs. 1.46±0.40 cm2, respectively; P<0.01), whereas average EOA for each valve size was significantly larger for the Trifecta than Magna group. One-year postoperatively, mean EOA for all valve sizes was significantly larger in the Trifecta than Magna group (1.64±0.40 vs. 1.50±0.42 cm2, respectively; P=0.01), whereas there was no significant difference in the EOA for the 23- or 25-mm valves between the 2 groups. At the latest follow-up, there was a significant difference in EOA only for the 21-mm valve. Interestingly, EOA in the Magna group remained unchanged, whereas that of the Trifecta group appeared to decrease over the study period (Figure 3B). There was no significant difference in EOA between the 2 groups over the study period.

Transthoracic echocardiographic assessment of the effective orifice area (EOA) for each valve: (A) unadjusted (actual) data and (B) interaction between time points (at discharge, 1 year postoperatively, at follow-up) and valve type (Trifecta vs. Magna).

LVM was calculated based on transthoracic echocardiographic data. The LVMi regression rate was defined by the ratio of LVMi at each time point to preoperative LVMi. There was a steady decrease in LVMi in both groups over the study period, reaching a 25±29.1% and 29.1±18.8% reduction in the Trifecta and Magna groups, respectively (Figure 4A). LVMi reduction appeared to predominate in the Magna compared with Trifecta group, although the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 4B).

Transthoracic echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular mass index (LVMi) for each valve: (A) unadjusted (actual) data and (B) interaction between time points (at discharge, 1 year postoperatively, at follow-up) and valve type (Trifecta vs. Magna).

There was no significant difference in the incidence of severe patient-prosthesis mismatch in either group over the study period. Severe patient-prosthesis mismatch was observed in 5 patients (4.8%) in the Trifecta group and in 38 patients (10.7%) in the Magna group at discharge (log-rank test, P=0.0595), in 3 (2.9%) and 21 (5.9%) patients, respectively, at 1 year (log-rank test, P=0.218), and in 3 (2.9%) and 20 (5.6%) patients, respectively, at the latest follow-up (log-rank test, P=0.211).

This study compared institutional clinical and hemodynamic outcomes after AVR using Trifecta and Magna bioprostheses. Neither in-hospital nor midterm clinical outcomes were significantly different when comparing the 2 valves because patient characteristics and surgical procedures did not differ significantly, including the size of the prosthesis selected. Echocardiographically, MPG across the prosthetic valve was significantly lower in the Trifecta than Magna group soon after surgery; however, this difference decreased over the study period. EOA of the prosthetic valve showed a similar trend to MPG soon after surgery, with no significant difference in EOA between the groups over the study period. LVM regressed substantially in both groups, with no significant difference in the degree of regression between the 2 groups over the study period. In addition, there was no significant difference in the incidence of severe patient-prosthesis mismatch between the groups over the study period.

A hemodynamic advantage was echocardiographically more prominent for the Trifecta than Magna valve soon after surgery. We attributed this to the design of the valves, with the valve leaflets mounted outside the sewing ring on the Trifecta valve and inside the sewing ring on the Magna valve, which created a larger orifice area on the Trifecta valve. This hemodynamic advantage gradually diminished over time, and was related, at least in part, to an immunological reaction with the deposition of platelets and subsequent fibrin formation with leaflet thickening and pannus formation.14 However, further follow-up and/or an in vivo study are required to prove this theory. One may claim that the hemodynamic advantage of the Trifecta valve was not reflected in our clinical outcomes regarding the degree of LVM regression or patient-prosthesis mismatch. Possible reasons for this are the small number of patients and/or, possibly more importantly, the relatively short period of the hemodynamic advantage, which was insufficient to produce substantial differences in the outcomes, including LVM regression, even in Japanese patients, and the relatively small size of the prosthesis compared with those used in Western patients.

Redo valve surgery may be required in patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve replacement, and the aortic ViV procedure is an option in these patients. Therefore, it is important to select the valve prosthesis while considering possible future aortic ViV. Because the Trifecta valve has externally mounted leaflets with a rigid sewing cuff, aortic ViV with a Trifecta valve reportedly has the following disadvantages: (1) expanding the externally mounted Trifecta leaflets potentially obstructs the coronary artery ostia;9 and (2) ViV then requires a smaller transcatheter heart valve size than the implanted valve, which has a rigid sewing cuff that cannot be broken by balloon expansion. In fact, it was reported that aortic ViV with the 26-mm Sapien XT (Edwards Lifesciences) over a 25-mm Trifecta valve led to significantly high coronary obstruction rates compared with the 23-mm Sapien XT,15 although some reports state that aortic ViV was safely performed over the 23-mm Trifecta valve using a St. Jude Medical Portico 23-mm valve or a 23-mm Medtronic Core-Valve Evolut valve (Medtronic).16,17 In contrast, obstruction of the coronary ostia reportedly rarely occurs with aortic ViV over a Magna valve, in which the leaflets are mounted internally. Previous reports also state that it is possible to fracture the sewing cuff of the Magna valve with the high-pressure balloon to accept a 1-mm larger transcatheter heart valve than the labeled valve size, ex vivo.18 Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest the Magna valve for patients who are likely to need a second valve replacement surgery.

This study is limited by its retrospective design. In addition, prosthetic valve selection (Trifecta vs. Magna) was not randomized, but instead was determined by individual surgeons who implanted the best-matched valve prosthesis for each patient. Selection bias may be minimal because there was no significant difference in patient background and characteristics between the 2 groups. Postoperative follow-up periods also significantly differed between the 2 groups, potentially introducing analytical bias. However, the patients’ background and characteristics and the surgical procedures, including prosthesis size, were almost identical between the 2 groups. In addition, we used appropriate statistical methods, such as the validated statistical linear mixed model, to eliminate potential bias related to different follow-up periods.

In conclusion, post-AVR clinical outcomes, including LVM regression and patient–prosthesis mismatch, did not differ significantly between the Trifecta and Magna valves. Although hemodynamic performance of the valve prosthesis was greater for the Trifecta valve at least until 1-year after AVR, this difference diminished gradually over time.

The authors thank Jane Charbonneau (Edanz Group; www.edanzediting.com/ac) for the English language editing of a draft of this manuscript.

This work was not supported by a specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

None declared.