2021 Volume 85 Issue 5 Pages 584-594

2021 Volume 85 Issue 5 Pages 584-594

Background: In the Prospective Comparison of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) With ACEi to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) study, treatment with sacubitril/valsartan reduced the primary outcome of cardiovascular (CV) death and heart failure (HF) hospitalization compared with enalapril in patients with chronic HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). A prospective randomized trial was conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan in Japanese HFrEF patients.

Methods and Results: In the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEi to determine the noveL beneficiaL trEatment vaLue in Japanese Heart Failure patients (PARALLEL-HF) study, 225 Japanese HFrEF patients (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class II–IV, left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≤35%) were randomized (1 : 1) to receive sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg bid or enalapril 10 mg bid. Over a median follow up of 33.9 months, no significant between-group difference was observed for the primary composite outcome of CV death and HF hospitalization (HR 1.09; 95% CI 0.65–1.82; P=0.6260). Early and sustained reductions in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) from baseline were observed with sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril (between-group difference: Week 2: 25.7%, P<0.01; Month 6: 18.9%, P=0.01, favoring sacubitril/valsartan). There was no significant difference in the changes in NYHA class and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) clinical summary score at Week 8 and Month 6. Sacubitril/valsartan was well tolerated with fewer study drug discontinuations due to adverse events, although the sacubitril/valsartan group had a higher proportion of patients with hypotension.

Conclusions: In Japanese patients with HFrEF, there was no difference in reduction in the risk of CV death or HF hospitalization between sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril, and sacubitril/valsartan was safe and well tolerated.

Heart failure (HF) affects ∼26 million people worldwide and represents a global pandemic1 associated with high mortality rate and reduced quality of life (QoL).2 With ∼26% of its population aged >65 years, Japan is particularly challenged by the HF epidemic.3 It is expected that by 2030, the number of Japanese patients with HF will reach ∼1.3 million.4

HF guidelines in Japan recommend angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) for the treatment of HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).5 A recent study showed that despite treatment with a standard of care (SoC), the prognosis of Japanese patients hospitalized with HF remains poor, with 7% in-hospital mortality, 17% mortality, and 46% rehospitalization within a median follow-up period of 19 months (range: 3–26), indicating the need for a novel therapeutic approach for HF in addition to a SoC.6

The Prospective Comparison of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) With ACEi to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial demonstrated the superiority of sacubitril/valsartan (LCZ696) over enalapril, as evidenced by a 20% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular (CV) death and hospitalization for HF observed in patients with HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <35%).7 Based on this evidence, sacubitril/valsartan has been approved for treatment of chronic HFrEF (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class II–IV) in over 100 countries worldwide and is recommended by clinical practice guidelines as a replacement for ACEi/ARBs to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic HFrEF.8,9

Additionally, based on evidence from the TRANSITION and PIONEER-HF trials,10–12 the updated American College of Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology expert consensus statements recommend initiation of sacubitril/valsartan for patients hospitalized with new-onset HF or decompensated chronic HF with and without prior exposure to ACEi/ARBs.13,14

The PARADIGM-HF trial randomized 8,442 patients with HFrEF from 47 countries, including 18% from the Asia-Pacific region, with no variation in the treatment benefit observed by region; however, no patients were enrolled from Japan.7,15 The current study, Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEi to determine the noveL beneficiaL trEatment vaLue in Japanese Heart Failure patients (PARALLEL-HF), was designed to confirm consistency with PARADIGM-HF in terms of efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril in Japanese patients with HFrEF.16

The study design and rationale for PARALLEL-HF have been previously published.16 Briefly, the study was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind study to assess the effect of sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg twice daily (bid) vs. enalapril 10 mg bid on CV mortality and HF hospitalization reduction in Japanese patients with HFrEF.

The Executive Committee designed and oversaw the conduct of the trial. The study was monitored by an independent data safety monitoring committee. All events of death, HF hospitalization and intensification of treatments due to worsening of HF, which could potentially fulfill the criteria for the primary or secondary outcomes, were assessed and reported to a Clinical Endpoint Committee (CEC) blinded to study drug assignment for adjudication against pre-specified study criteria. The CEC for PARALLEL-HF was the same as that for PARADIGM-HF, and applied the same adjudication criteria for clinical endpoints. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. All local regulatory requirements and sponsoring company policies were followed. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02468232).

Study PopulationThe study enrolled Japanese patients with chronic HFrEF (NYHA class II–IV; LVEF ≤35%), N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) ≥600 pg/mL, or NT-proBNP ≥400 pg/mL for those who had been hospitalized for HF within the last 12 months, and were being treated with stable doses of ACEi/ARBs for at least 4 weeks prior to study entry. All patients gave written informed consent prior to participation.

Patients with history of angioedema, symptomatic hypotension and/or with systolic blood pressure (SBP) <100 mmHg, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and serum potassium >5.2 mEq/L, were excluded.

Study TreatmentsEligible patients entered a 2-week, single-blind active-treatment run-in period in which they received sacubitril/valsartan 50 mg bid. At the end of the run-in period, patients who tolerated sacubitril/valsartan 50 mg bid entered the double-blind treatment period and were randomized (1 : 1) to receive sacubitril/valsartan 100 mg bid or enalapril 5 mg bid for 4 weeks. Randomized patients were stratified using NT-proBNP levels (<1,600 pg/mL or ≥1,600 pg/mL). If tolerated, these patients were then up-titrated to the target dose of sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg bid or enalapril 10 mg bid (Supplementary Figure 1).16

Study ObjectivesThe primary objective of the study was to assess the effect of sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg bid compared with enalapril 10 mg bid in addition to background HF treatment, in delaying the time to first occurrence of the composite outcome of CV death or HF hospitalization.

The key secondary objectives were to assess the effects of sacubitril/valsartan on: (1) the changes in NT-proBNP from run-in baseline to predefined time points of Weeks 4 and 8, and Month 6; (2) the time to first occurrence of CV death, HF hospitalization, or intensification of treatments due to documented episodes of worsening HF; (3) the changes in NYHA classification from baseline to predefined time points at Week 4 and 8, and Month 6; and (4) the changes in the clinical summary score for HF symptoms and physical limitations, as assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) at Week 8 and Month 6.

The other secondary objectives included assessment of the effects of sacubitril/valsartan on rate of CV death or total (first and recurrent) HF hospitalizations, clinical composite score and healthcare resource utilization, and safety and tolerability of sacubitril/valsartan, compared with enalapril.

Study AssessmentsEfficacy Assessments The list of assessments at each study visit has been published previously.16 Events of death, HF hospitalization and intensification of treatments due to worsening of HF, were adjudicated by the CEC for classifying the fatal events and determining whether pre-specified endpoint criteria16 were met for the non-fatal events. In addition, a pre-specified analysis of site-reported events, and post-hoc analyses of primary outcome with Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC) risk score adjustment and Clinical Data Adjudication Committee (CDAC) adjudication, were performed. An additional analysis using the funnel plot method was performed to assess the consistency of primary outcome in PARALLEL-HF with that from PARADIGM-HF. The KCCQ questionnaire used had 23 items covering physical function, clinical symptoms, social function, self-efficacy and knowledge, and QoL. The clinical composite assessment was based on patient global assessment of disease activity (7-point patient self-evaluation scale) and the NYHA functional classification.

Safety Assessments Safety and tolerability assessments included all adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs), sitting blood pressure, angioedema, hyperkalemia, renal dysfunction, and cough. The assessment of safety was based primarily on the frequency of AEs, SAEs, and laboratory abnormalities.

Statistical AnalysisThe target sample size was determined to ensure that there was at least 80% probability of observing a hazard ratio (HR) <1. Based on the PARADIGM-HF results,7 assuming a hazard reduction of 20% for the primary outcome of CV death and HF hospitalization with sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril, 57 primary endpoint events were estimated to be required. Assuming an annual event rate of 13% in the enalapril group, enrollment period of 22 months and minimum follow up of 18 months, a total sample size of 220 patients would be required to obtain 57 primary endpoint events. Statistical analysis methods are detailed in the Supplementary File.

In total, 307 patients were screened from 53 sites in Japan between June 2015 and December 2016, of whom 225 were randomized to receive sacubitril/valsartan (n=112) or enalapril (n=113) during the double-blind treatment period (Figure 1). Two patients who did not meet eligibility criteria but were randomized by mistake did not receive double-blind treatment and were not included in the analyses for efficacy and safety outcomes (one from each treatment group).

Patient disposition by treatment group. Patients who were re-screened were counted only once for the screen set and for the enrolled set.

Mean age of patients was 67.8 years at screening. Most patients were male (86.1%), NYHA class II (94.2%) and had a mean LVEF (28.2%). Almost 50% patients had ischemic HF etiology and 72.6% had a history of HF hospitalization. Other comorbidities common in the study population were hypertension (68.6%), diabetes mellitus (46.6%), and atrial fibrillation (34.1%). The patients were well treated with guideline-recommended evidence-based HF therapies at baseline, including ACEi/ARB in 62.8%/37.2%, β-blockers in 95.5%, and MRA in 59.6% (Supplementary Table 1). Of the patients receiving ACEi/ARB at baseline, 38.1% were receiving ≥10 mg/day (enalapril equivalent dose). In the sacubitril/valsartan group, only 3 patients (2.7%) received sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) at baseline; 0 patients received this in the enalapril group (P=0.1216). The proportion of patients on SGLT2i slightly increased during the double-blind treatment period; however, this was similar between the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups (10.8% vs. 11.6%, P=1.0). Overall, the demographics, medical history, and clinical characteristics were generally balanced between the 2 treatment groups. Compared with patients in the enalapril group, those in the sacubitril/valsartan group had a slightly lower body mass index (BMI). The proportion of patients with prior ischemic HF was higher in the sacubitril/valsartan group (51.4% vs. 43.8%), whereas hypertension was higher in the enalapril group (64.0% vs. 73.2%) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Sacubitril/valsartan (N=111) |

Enalapril (N=112) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 69.0 (9.7) | 66.7 (10.9) | 0.1019 |

| Age group, n (%), years | – | ||

| <65 | 29 (26.1) | 32 (28.6) | |

| ≥65 | 82 (73.9) | 80 (71.4) | |

| <75 | 79 (71.2) | 84 (75.0) | |

| ≥75 | 32 (28.8) | 28 (25.0) | |

| Male, n (%) | 96 (86.5) | 96 (85.7) | 0.8676 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 23.8 (4.0) | 25.1 (4.2) | 0.0216 |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 28.6 (5.1) | 27.7 (5.5) | 0.2172 |

| SBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 123.6 (17.8) | 121.2 (14.4) | 0.2636 |

| DBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 72.8 (13.2) | 72.8 (11.9) | 0.9950 |

| Heart rate (beats/min), mean (SD) | 73.9 (13.8) | 72.3 (12.2) | 0.3660 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean (SD) | 58.3 (17.6) | 57.6 (14.7) | 0.7336 |

| NT-proBNP at randomization (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 837.0 (563.0–1,476.0) | 841.0 (511.0–1,601.0) | 0.5706 |

| NT-proBNP at randomization, n (%), pg/mL | 0.5508 | ||

| <1,600 | 87 (78.4) | 84 (75.0) | |

| ≥1,600 | 24 (21.6) | 28 (25.0) | |

| NYHA class at randomization, n (%) | 0.8027 | ||

| I | 4 (3.6) | 4 (3.6) | |

| II | 101 (91.0) | 104 (92.9) | |

| III | 6 (5.4) | 4 (3.6) | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Medical history | |||

| Prior HF hospitalization, n (%) | 80 (72.1) | 82 (73.2) | 0.8483 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 71 (64.0) | 82 (73.2) | 0.3235 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 52 (46.8) | 52 (46.4) | 0.9501 |

| Prior angina pectoris, n (%) | 28 (25.2) | 29 (25.9) | 0.9090 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 51 (46.0) | 46 (41.1) | 0.4629 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 11 (9.9) | 10 (8.9) | 0.8019 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 36 (32.4) | 40 (35.7) | 0.6052 |

| Primary heart failure etiology, n (%) | 0.2557 | ||

| Ischemic | 57 (51.4) | 49 (43.8) | |

| Non-ischemic | 54 (48.6) | 63 (56.2) | |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| ACEi | 71 (64.0) | 69 (61.6) | 0.7158 |

| ARB | 40 (36.0) | 43 (38.4) | 0.7158 |

| MRA | 64 (57.7) | 69 (61.6) | 0.5478 |

| Diuretics | 91 (82.0) | 95 (84.8) | 0.5687 |

| β-blocker | 105 (94.6) | 108 (96.4) | 0.5082 |

| CRT/ICD | 16 (14.4) | 26 (23.2) | 0.0929 |

Full analysis set. Baseline parameters in the table were at screening, unless specified otherwise. –, not available; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; CRT/ICD, cardiac resynchronization therapy/ implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Majority of the patients were successfully up-titrated to the target dose by Week 8: 75.0% of patients in the sacubitril/valsartan group to 200 mg bid and 86.5% of patients in the enalapril group to 10 mg bid. More than two-thirds of patients in the sacubitril/valsartan group (75.8%) and enalapril group (82.1%) were successfully up-titrated to the target dose by the end of the study and the majority remained on the target dose throughout the study. More than 70% of patients completed study treatment (73.9% in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 71.4% in the enalapril group). Among patients who were taking study medication at the final visit, the mean daily dose was 328.4 mg/day in the sacubitril/valsartan group and 17.2 mg/day in the enalapril group.

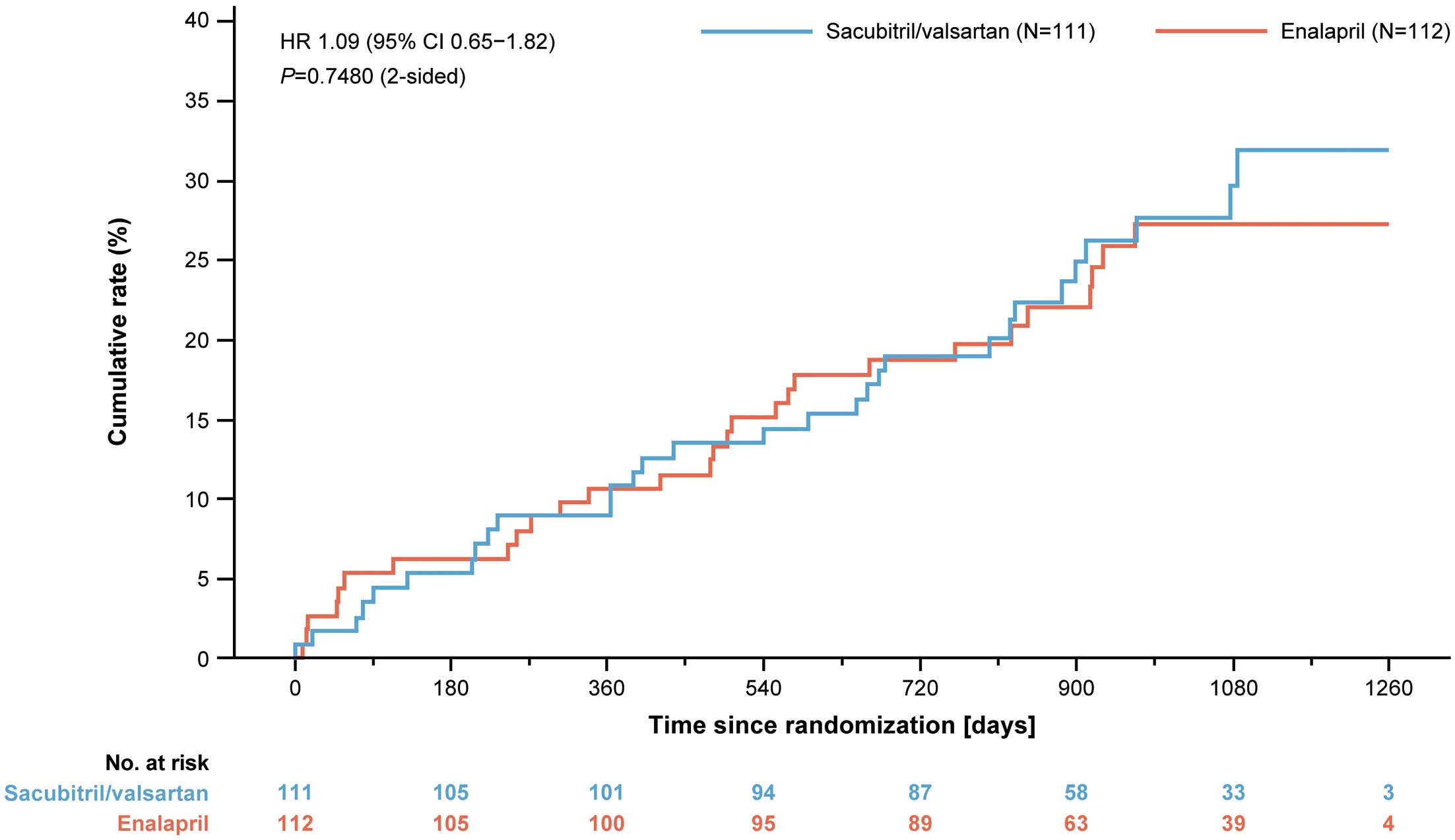

Efficacy OutcomesThe primary composite outcome of CEC-confirmed CV death and first hospitalization for HF occurred in 30 (27.0%) patients in the sacubitril/valsartan group compared with 28 (25.0%) in the enalapril group (HR 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65–1.82; P=0.6260). No between-group difference was observed for individual components of the primary composite outcome: adjudicated CV death (P=0.6493) and first hospitalization for HF (P=0.7851; Table 2). Overall, the 2 treatment groups did not differ in the risks of the primary composite outcome and its component (Figure 2; Table 2).

| Sacubitril/valsartan (N=111), n (%) |

Enalapril (N=112), n (%) |

Sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value* | |||

| Primary composite outcome | ||||

| CV death or HF hospitalization | 30 (27.0) | 28 (25.0) | 1.09 (0.65–1.82) | 0.6260 |

| CV death | 13 (11.7) | 11 (9.8) | 1.17 (0.52–2.61) | 0.6493 |

| First HF hospitalization | 25 (22.5) | 20 (17.9) | 1.27 (0.70–2.28) | 0.7851 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| CV death, HF hospitalization, or worsening of HF | 37 (33.3) | 37 (33.0) | 1.02 (0.65–1.62) | 0.5406 |

| Worsening of HF | 12 (10.8) | 14 (12.5) | 0.85 (0.40–1.85) | 0.3448 |

| CV death and total (first and recurrent) HF hospitalization |

44 (39.6) | 50 (44.6) | 0.87 (0.48–1.59)† | 0.6501 |

Full analysis set. *One-sided P value. †Rate ratio (95% CI). CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Kaplan-Meier plot for primary outcome (composite of cardiovascular death or first heart failure hospitalization) by treatment group. The HR and its CIs are estimations from a Cox-regression model with treatment and stratification of screening NT-proBNP as fixed factors. P value is 2-sided and is based on this model. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Similar results were obtained for MAGGIC risk score-adjusted analysis of primary composite outcome (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.58–1.65, P=0.4675), for CDAC-confirmed adjudicated primary outcome (HR 0.97; 95% CI 0.58–1.61, P=0.4471), and for site-reported primary composite outcome (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.60–1.60, P=0.4704) (Supplementary Table 2). Results from the funnel plot suggested that the HR in PARALLEL-HF was within the range of variation of HRs for countries with a similar number of events in PARADIGM-HF (Supplementary Figure 2).

The secondary efficacy CV outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The total number of CEC-confirmed CV deaths and total (first and recurrent) hospitalizations for HF was numerically lower in patients treated with sacubitril/valsartan (44 events) compared with enalapril (50 events) (rate ratio [RR] 0.87; 95% CI 0.48–1.59, P=0.6501). Analysis of the primary composite outcome by pre-specified subgroups defined according to demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of interest demonstrated consistent results (Figure 3).

Forest plot for first primary outcome (CV death or HF hospitalization) comparing sacubitril/valsartan with enalapril for pre-specified subgroups ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 50 mg bid for 2 weeks during the run-in period reduced plasma NT-proBNP levels by 21.3% and 22.9% among patients in the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups respectively. Thereafter, 2 weeks of treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 100 mg bid post-randomization reduced NT-proBNP levels by 27.1% from the run-in baseline compared to 1.9% reduction with enalapril 5 mg bid (i.e., 20% increase in NT-proBNP levels post-randomization). After 4 weeks of treatment, post-randomization, reduction in NT-proBNP levels was significantly greater with sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril (23.3% vs. 11.4%). Treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg bid until 6 months’ post-randomization reduced NT-proBNP by 30.5% from the run-in baseline compared to a 14.4% reduction with enalapril 10 mg bid. Compared with the enalapril group, a statistically significant reduction in NT-proBNP in the sacubitril/valsartan group was observed as early as Week 2 (between-group difference in percentage reduction 25.7%, P<0.0001). At Week 4 and Week 8, the between-group differences in percent reductions in NT-proBNP were 13.4% (LSM [least square means] of ratio 0.87; 95% CI 0.76–0.99, P=0.0326) and 14.6% (LSM of ratio 0.85; 95% CI 0.75–0.97, P=0.0161), respectively. This beneficial effect of sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril was maintained through Month 6, with a 18.9% difference between the reductions in the 2 groups (LSM of ratio 0.81; 95% CI 0.69–0.95, P=0.0104) (Figure 4).

Effect of sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril on change in NT-proBNP levels from run-in baseline to predefined time points. Geometric mean was exponentially back-transformed from the least square mean based on the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. CI, confidence interval; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

The sacubitril/valsartan group had numerically more patients with improvement in NYHA functional class from randomization to Week 8 compared with the enalapril group (13.5% vs. 10.8%). Overall, there was no significant difference in the NYHA functional class improvement between the 2 treatment groups at predefined time points (Week 4, Week 8, Month 6, and last assessment: P=0.7115, 0.1752, 0.2688 and 0.5798, respectively). Notably, the proportion of patients whose NYHA functional class worsened from baseline was lower in the sacubitril/valsartan group than in the enalapril group at Week 4 (0.9% vs. 4.5%), Week 8 (0.9% vs. 5.4%), Month 6 (0.9% vs. 7.3%) and last assessment (5.4% vs. 9.0%) (Figure 5). A similar trend was observed at the last assessment visit.

Effect of sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril on NYHA functional class from baseline to predefined time points. P value was calculated between the treatment groups for each timepoint and was based on Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests with modified ridit assessments. NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Compared with enalapril, sacubitril/valsartan showed a trend to a lesser deterioration of KCCQ clinical summary score for HF symptoms, and physical limitations from randomization to pre-specified time points of Week 8 (LSM change from baseline for sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril: −0.05 vs. −2.59; P=0.1854) and Month 6 (−2.22 vs. −3.49; P=0.5737). The proportion of patients with 5-point improvement in KCCQ clinical summary score tended to be greater in the sacubitril/valsartan group than in the enalapril group (24.6% vs. 15.7% at Week 8; and 17.3% vs. 13.2% at Month 6), which, however, did not reach statistical significance.

Clinical composite assessment change from randomization was similar between the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups. The proportion of patients with worsened score tended to be less in the sacubitril/valsartan group vs. the enalapril group at Week 8 (1.8% vs. 7.2%; P=0.1372), Month 6 (8.2% vs. 10.0%; P=0.6211), and Month 18 (14.8% vs. 20.4%; P=0.9507). A similar trend was observed for patient global assessment of disease activity, with a relatively higher proportion of patients showing moderate improvement in the sacubitril/valsartan group than in the enalapril group at Week 8 (9.1% vs. 6.5%; P=0.8791) and Month 6 (10.9 vs. 5.7; P=0.1666).

There was a trend in favor of sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril for CEC-confirmed total HF hospitalizations (31 vs. 39 events; RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.44–1.58), for mean number of days in the hospital/patient-year (12.7 vs. 14.6 days; RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.45–1.66), for total number of emergency room visits for HF (15 vs. 30 visits; RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.19–1.07), and for the total number of days in the intensive care unit per patient-year (0.50 vs. 0.35 days; RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.23–5.11).

SafetyThe proportion of patients experiencing any AEs was comparable between sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups (98.2% vs. 96.4%, P=0.6832) during the double-blind treatment period. The most commonly reported AEs, regardless of study treatment relationship during the double-blind treatment period, were nasopharyngitis (47.5%), cardiac failure (31.8%) and hypotension (16.6%). Of note, the incidence of hyperkalemia was higher in the enalapril group compared with the sacubitril/valsartan group (15.2% vs. 11.7%; Supplementary Table 3). A similar proportion of patients had a SBP <90 mmHg in the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups (22.5% vs. 21.4%, P=0.8727), whereas the proportion of patients who experienced hypotension (reported AE) with SBP <90 mmHg was higher in the sacubitril/valsartan group (11.7% vs. 4.5%, P=0.0526). Fewer patients in the sacubitril/valsartan group compared with the enalapril group had renal impairment (serum creatinine ≥2.0 mg/dL) (6.3% vs. 9.8%, P=0.4619). A similar trend was observed for patients experiencing a cough (7.2% vs. 9.8%; P=0.6326). The proportion of patients with elevated serum potassium levels (≥5.5 mmol/L) was comparable between sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups (7.2% vs. 5.4%, P=0.5944). There were fewer patients with site-reported angioedema events in the sacubitril/valsartan group compared with the enalapril group (1.9% vs. 2.7%). However, no case of adjudication committee-confirmed angioedema was reported in either treatment group (Table 3).

| Adverse event | Sacubitril/valsartan (N=111), n (%) |

Enalapril (N=112), n (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotension with | |||

| Hypotension* with SBP <90 mmHg | 13 (11.7) | 5 (4.5) | 0.0526 |

| SBP <90 mmHg | 25 (22.5) | 24 (21.4) | 0.8727 |

| Elevated serum creatinine (mg/dL) | |||

| ≥2.0 | 7 (6.3) | 11 (9.8) | 0.4619 |

| ≥2.5 | 2 (1.8) | 4 (3.6) | 0.6832 |

| ≥3.0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1.0 |

| Elevated serum potassium (mmol/L) | |||

| ≥5.5 | 8 (7.2) | 6 (5.4) | 0.5944 |

| ≥6.0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1.0 |

| Cough | 8 (7.2) | 11 (9.8) | 0.6326 |

| Angioedema† | 0 | 0 | – |

*Based on reported term. †None of the site-reported angioedema events were confirmed by the Angioedema Adjudication Committee (AAC). Additionally, no patients were treated with antihistamines, catecholamines, steroids or required mechanical airway protection. –, not available; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The incidence of SAEs was similar in the sacubitril/valsartan and enalapril groups (57.7% vs. 54.5%), and the most frequently observed SAEs included cardiac failure (16.2% vs. 19.6%), and pneumonia (5.4% vs. 1.8%) (Supplementary Table 4).

Permanent discontinuation of treatment due to AEs was slightly higher in the enalapril group (11.6% vs. 9.9%). Also, more AEs led to temporary interruption or dose adjustment in the enalapril group (16.1%) compared to the sacubitril/valsartan group (10.8%).

The results from this study demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the risk of CV death or first HF hospitalization with sacubitril/valsartan (target dose 200 mg bid) vs. enalapril (target dose 10 mg bid) in Japanese patients with HFrEF (LVEF ≤35%). However, sacubitril/valsartan was associated with significant and sustained reduction in NT-proBNP at Week 2, which was maintained until Month 6. There was a trend to improvement with sacubitril/valsartan in NYHA class and a lesser deterioration in the KCCQ clinical summary score for symptoms and physical limitations at Week 8 and Month 6; however, this did not reach statistical significance.

The safety and efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan have already been demonstrated in the PARADIGM-HF trial (sacubitril/valsartan 200 mg vs. enalapril 10 mg bid) among patients with chronic HFrEF.7 As demonstrated in the PARADIGM-HF trial,7 PARALLEL-HF was designed to show consistency in clinical benefits of sacubitril/valsartan vs. enalapril, which is the most extensively studied ACEi in Japanese patients with chronic HFrEF.17

Similar to PARADIGM-HF, enalapril 10 mg bid was selected as the active comparator target dose for this study based on its ability to reduce the risk of death or hospitalization as demonstrated in the SOLVD-Treatment study.7,17 Although enalapril 10 mg bid is considered high for Japanese patients in clinical practice, 38.1% of patients treated with ACEi/ARB at baseline were on ≥10 mg/day of enalapril or an equivalent dose in PARALLEL-HF, and enalapril was observed to be well tolerated. Approximately 64% of patients achieved the target dose of 10 mg bid enalapril and a mean daily dose 17.2 mg. This is comparable with the SOLVD-Treatment study where 49% of patients achieved enalapril 10 mg bid at final visit and a mean daily dose of 16.6 mg.17 In PARALLEL-HF, higher doses of enalapril may have enhanced its treatment effects, thus resulting in a small treatment difference between enalapril and sacubitril/valsartan.

Importantly, compared with PARADIGM-HF, patients in PARALLEL-HF received a lower dose of sacubitril/valsartan (50 mg bid) in the single-blind active treatment run-in period because the approved doses of ACEi/ARBs in Japan are generally lower than that of those in other countries.5,7,16 The dose was up-titrated to 200 mg bid over 6 weeks based on the observations in the TITRATION study.18

In PARALLEL-HF, patients were stable with mild-to-moderate HF symptoms (mostly NYHA class II), and the prevalence of other comorbidities was similar to those observed in the other contemporary Japanese clinical trials and registries.6 Compared with patients in PARADIGM-HF, patients in PARALLEL-HF were older, mostly belonged to NYHA class II, and had lower BMI, SBP/diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and median NT-proBNP levels at randomization. These variations reflect the characteristics of the study patient population in Japan (Supplementary Table 1).19 The subgroup analyses, including NYHA class (I/II vs. III/IV) and NT-proBNP levels (<1,600 pg/mL vs. ≥1,600 pg/mL) demonstrated consistent results (Figure 3). The MAGGIC risk score was slightly higher in PARALLEL-HF than in PARADIGM-HF (median [IQR]: 23 [19–26] vs. 20 [16–24]).20 However, score distribution was similar between studies, suggesting that mortality risk for patients enrolled in PARALLEL-HF was similar to that in PARADIGM-HF.7,19

Additionally, patients in PARALLEL-HF were well treated with evidence-based HF therapy, including ACEi, ARB, β-blocker, MRA, or diuretic, prior to study enrollment (Table 1). The percentages of use of the latter three classes of agents were similar to those in the PARADIGM-HF study (Supplementary Table 1).19 PARALLEL-HF had a median follow up of 33.9 months in the sacubitril/valsartan group with no patient lost to follow up, compared with 27 months in PARADIGM-HF.7

In this well-treated cohort of Japanese HFrEF patients, the primary composite outcome of CEC-confirmed CV death or HF hospitalization was similar between the 2 treatment groups (HR 1.09 [95% CI, 0.65–1.82]; P=0.6260) (Table 2, Figure 2). The analysis adjusted for baseline mortality risk (MAGGIC score) revealed wide 95% CIs for HR, which is similar to the primary analysis (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.58–1.65, P=0.4675). A similar trend was observed for results from efficacy analysis of CDAC-confirmed primary outcome (HR 0.97; 95% CI 0.58–1.61, P=0.4471) (Supplementary Table 2). This indicates that variation in prognostic factors due to the small sample size influenced the results of primary analysis. Subsequent analysis of the primary outcome using a funnel plot showed that the range of variation of events was similar between the 2 studies (Supplementary Figure 2), with a high likelihood that sacubitril/valsartan would reduce risk of CV death and HF hospitalization in Japanese patients.

Importantly, the sacubitril/valsartan group showed a statistically significant reduction in levels of NT-proBNP from baseline to Month 6 compared with the enalapril group. Treatment with sacubitril/valsartan 50 mg bid during a 2-week run-in period reduced NT-proBNP by 21.3% which, unlike enalapril, further reduced with sacubitril/valsartan after randomization; 23.3% reduction at Week 4 and 30.5% reduction at Month 6 (Figure 4). Compared with the enalapril group, there was a significant reduction in NT-proBNP at Week 2 (25.7%, P<0.0001), which was sustained even at Month 6 (18.9%, P=0.0104). This is in line with the early and sustained improvement in biomarkers of myocardial wall stress and injury by sacubitril/valsartan in PARADIGM-HF.21

Sacubitril/valsartan at a target dose of 200 mg bid could provide overall favorable results in clinical efficacy over enalapril 10 mg bid for Japanese HFrEF patients. From a safety perspective, sacubitril/valsartan at a target dose of 200 mg bid was well tolerated compared with enalapril at a target dose of 10 mg bid in the PARALLEL-HF study (Table 3, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Compared with enalapril, fewer patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan discontinued study medication due to AEs. Although hypotension was more frequently reported among patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan, this AE rarely resulted in permanent discontinuation of study medication (<2%). Hyperkalemia and renal impairment tended to be more commonly reported in the enalapril group vs. the sacubitril/valsartan group which, however, was not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 3). There were no cases of Angioedema Adjudication Committee-confirmed angioedema in any group during the study (Table 3).

PARALLEL-HF was associated with a few limitations. First, the sample size estimation was based on feasibility considerations. The small sample size and low event rates limit drawing inferences about efficacy of sacubitril/valsartan with statistical significance. Due to the small sample size, one could not expect results comparable to PARADIGM-HF in magnitude. Second, the improvements in NYHA functional class and KCCQ score observed with sacubitril/valsartan were suggestive of its benefits, but were not statistically significant (Figure 5).

PARALLEL-HF could not conclusively demonstrate the superiority of sacubitril/valsartan over enalapril in Japanese patients with HFrEF. However, totality of data, including favorable changes in NT-proBNP and trends of improvement in NYHA functional class and QoL, were consistent with effects observed for the global population in PARADIGM-HF. In conclusion, sacubitril/valsartan has been demonstrated to be safe, well tolerated and beneficial in Japanese patients with chronic HFrEF.

The authors thank all the patients, investigators, and staff who participated in this study. We also thank Tripti Sahu and Shalini Verma (Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, India) for providing medical writing assistance and editorial support. All authors participated in the development and writing of the paper, reviewed and critically revised the manuscript for content, and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

H.T. was an Executive Committee Chair of PARALLEL-HF and has received consultation fees from Novartis Pharma K.K., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Yakuhin, Ono Pharmaceutical; and remuneration from MSD, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Bayer Yakuhin, Novartis Pharma K.K., Kowa Pharmaceutical, Teijin Pharma; research funding from Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, IQVIA Services, Omron Healthcare; and scholarship funds from Astellas Pharma, Novartis Pharma K.K., Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Teijin Pharma, MSD.

S.M. was an Executive Committee member of PARALLEL-HF and has received speakers’ bureau/honorarium from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, MSD, Pfizer, Bayer Yakuhin, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Toa Eiyo, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Japan, Philips Respironics GK, Teijin Pharma, Medtronic Japan, St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific Japan, and Torii Pharmaceutical; honorarium for writing promotional material for Medtronic Japan, Teijin Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin; research funds from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, MSD, Pfizer, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Toa Eiyo, Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Teijin Pharma, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, Abbott, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, and Bayer Yakuhin; and consultation fees from Novartis Pharma K.K.

Y. Saito was an Executive Committee member of PARALLEL-HF and has received research funds from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Kirin, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Shionogi & Co., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Teijin Pharma, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis Pharma K.K., Pfizer and Fuji Yakuhin; research expenses from Novartis Pharma K.K., Roche Diagnostics, Amgen, Bayer Yakuhin, Astellas Pharma and Actelion Pharmaceuticals; speakers’ bureau/honorarium from Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Tsumura & Co., Teijin Pharma, Toa Eiyo, Nippon Shinyaku, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma K.K., Bayer Yakuhin, Pfizer Japan, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Mochida Pharmaceutical; and consultation fees from Ono Pharmaceutical and Novartis Pharma K.K.

H.I. was an Executive Committee member of PARALLEL-HF and has received speakers’ bureau/honorarium from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, MSD, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Toa Eiyo, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Medtronic Japan, Astellas Pharma, Bayer Yakuhin, and Ono Pharmaceutical; research funds from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, MSD, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Toa Eiyo, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Medtronic Japan, Astellas Pharma, Bayer Yakuhin, Shionogi, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, and Ono Pharmaceutical; honorarium for writing promotional material for Daiichi-Sankyo; consultation fees from Novartis Pharma K.K., and is affiliated with an endowed department sponsored by Medtronic Japan.

K.Y. was a Medical Advisor of PARALLEL-HF and has received speakers’ bureau/honorarium from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis Pharma K.K.; and research funds from Abbott, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Medtronic Japan, Daiichi-Sankyo, Biotronik Japan, Japan Lifeline, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Fukuda Denshi, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Novartis Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, Boston Scientific; and consultation fees from Novartis Pharma K.K..

Y. Sakata was a Data Monitoring Committee member of PARALLEL-HF and reports no conflicts of interest.

A.S.D. has received research grant support (to Brigham and Women’s Hospital) from Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Bayer, and Novartis; and has received consulting fees or honoraria from Abbott, Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biofourmis, Boston Scientific, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Merck, Novartis, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma.

W.G., T.O., T.I. and T.K. were employees of Novartis at the time of the study.

H.T., Y. Saito, H.I., K.Y., and Y. Sakata are members of Circulation Journal’s Editorial Team.

The study protocol and all amendments were reviewed and approved by the Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) or Institutional Review Board (IRB) for each center (e.g., Nihon University Hospitals Joint IRB [reference number: 5010005002382]). A list of IECs and IRBs are included in the Supplementary Appendix.

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-20-0854