2022 Volume 86 Issue 1 Pages 116-117

2022 Volume 86 Issue 1 Pages 116-117

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a morphological diagnosis granted for an etiologically heterogeneous group of pathologies that involve dysfunction of the myocardium.1 DCM can affect not only adults, but also children as early as infancy, becoming the most common cause of pediatric heart failure.2–4 The majority of deaths occur during infancy, imposing a serious burden of premature deaths on society.5 Pediatric DCM had been therapeutically approached just as if it morphologically resembled the adult form, with the use of common classical pharmacotherapies such as β-blockers and/or renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. It ends up, however, that we once again are taught that “children are not small adults”. The adoption of adult-based heart failure pharmacotherapy has so far only led to a less promising outcome, and thus pediatric DCM still remains one of the most intractable cardiac conditions.5 Vigorous investigation of the molecular basis of pediatric DCM has finally led to our current understanding that it substantially differs from the adult-onset form, in terms of its underlying molecular responses and thus treatment as well.6–8

Article p 109

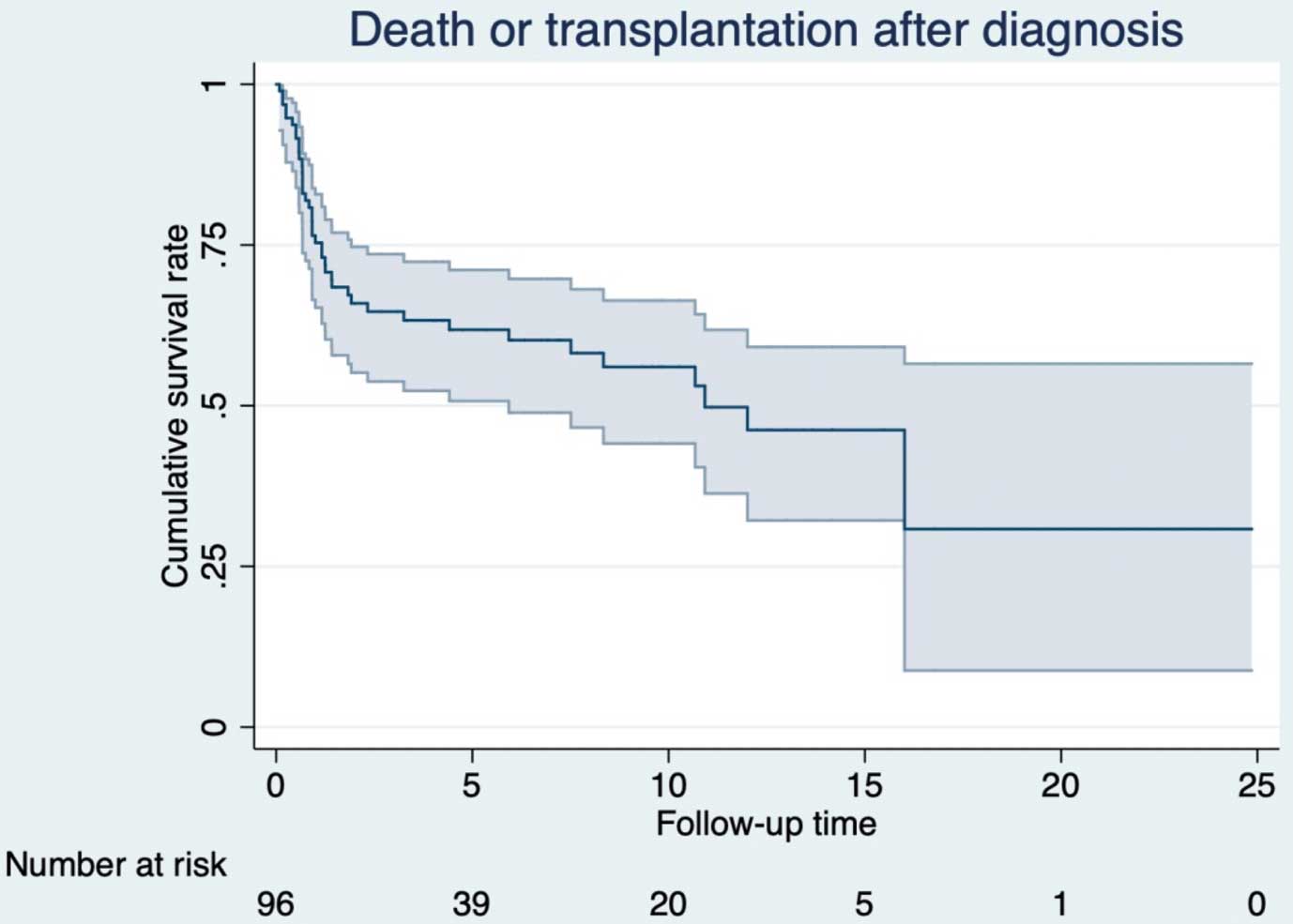

In this issue of the Journal, Mori and his collaborators9 examine the contemporary practice standards and the resultant prognosis of pediatric DCM in Japan. After excluding those with secondary cardiac dysfunctions, a total 106 children diagnosed as DCM between 1990 and 2014 were included in the multicenter retrospective study. Most importantly, the 5-year cumulative incidence of the composite outcome of death and transplantation (34%) was reported to greatly exceed the fraction receiving a transplant during the period (15%). These discrepant figures indicate a disproportionately large number of potentially avoidable, pediatric DCM deaths occurring while awaiting a transplant. Behind this lies the fact that heart transplant was never a realistic nor accessible treatment option for pediatric heart failure until 2010, when Japan’s Organ Transplant Law was revised to permit children below age 15 to become donors of an organ. A huge gap still exists between the potential need for pediatric heart transplants and the actual numbers performed, rendering Japan facing one of the world’s most serious shortages in donor hearts. Regardless of such differences in heart transplantation practices, equally of note, however, is that the trend in overall survival in the Japanese cohort was comparable to that reported by other large pediatric DCM registries.5,10 A steep initial decline in survival during the first year after diagnosis (Figure),9 a shared trend among various registry data, suggests the existence of a spared population yet to be efficiently addressed by targeted therapeutic approaches.

Freedom from death of Japanese children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Decline in survival during the initial year is followed by relative plateauing. Adopted with permission from Mori H, et al.9

This article, for the first time, presents Japan’s present status in the care of pediatric DCM patients, for which nationwide information had been very sparse. An estimate of the pediatric DCM disease burden has now been provided, and both unique and shared challenges among global heart failure societies are highlighted. Now, aside from the serious shortage in organ transplant donors, which other critical issues are we to next address? Although not approached in the current article,9 the fractions of participants who received a biopsy to rule out probable myocarditis, or who underwent genetic/metabolic diagnostic workup to molecularly define any possible heritable disease, neuromuscular disorder, or inborn error of metabolism underlying the cardiac dysfunction, definitely deserves attention. Because, for example, favorable outcomes are likely to follow biopsy-proven myocarditis,10 and other overlooked diagnoses of underlying systemic illnesses may also critically affect the interpretation of patient pathophysiology, reaching an etiological explanation for the DCM morphology is the first step towards personalized care. Endomyocardial biopsy has prognostic value in suspected myocarditis, but an update on its performance rate is lacking in Japan.11 Limited access to genetic services is another serious issue in our setting. When Japan launched the rare disease initiative in 2015, with the aim of facilitating phenotypic and genetic data matching, we were already years behind our international counterparts.12 Genetic testing had long been available only on a research basis, confined to skilled laboratories,13,14 and is still only partly implemented as part of Japanese public healthcare. Registries being the main sources of real-world data on molecular etiology, current best practice, and outcome, participating may itself simply improve guideline adherence and minimize practice variability. With rigorous endeavor as a whole, we ought to enhance the molecular diagnosis rate in Japanese children with DCM, which could be as high as 35%.15 Listed above are only some of the possible approaches to mitigating the persistently detrimental survival outcomes.

Registry stakeholders are not limited to the affected individuals or their treating clinicians. To make the best of a pediatric cardiomyopathy registry, the fruit of excellent team effort, pharmaceutical industries and regulatory agencies also shall take part, as the registry has the potential to stimulate drug development by offering a patient platform for the evaluation of investigational drugs and medical devices. Serious needs still unmet are pushing the global heart failure society towards a research odyssey focused on targeted therapeutics not only relevant but possibly unique to pediatric heart failure. As mentioned earlier, a DCM diagnosis is a mere morphological description of molecularly heterogeneous disease entities. It is high time we, scientists and clinicians, stop clinging to historical, morphology-based classifications of cardiomyopathies, and move in the direction of enriching our pediatric DCM registry with more molecular diagnoses that may actually become actionable in the near future.

The authors have received research grants from the Japanese Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery (Y.N.) and the Japanese Circulation Society (M.I.).

M.I. belongs to an endowed department supported by Anges Inc (Tokyo, Japan).