2024 Volume 88 Issue 3 Pages 390-407

2024 Volume 88 Issue 3 Pages 390-407

Background: Despite the importance of implementing the concept of social determinants of health (SDOH) in the clinical practice of cardiovascular disease (CVD), the tools available to assess SDOH have not been systematically investigated. We conducted a scoping review for tools to assess SDOH and comprehensively evaluated how these tools could be applied in the field of CVD.

Methods and Results: We conducted a systematic literature search of PubMed and Embase databases on July 25, 2023. Studies that evaluated an SDOH screening tool with CVD as an outcome or those that explicitly sampled or included participants based on their having CVD were eligible for inclusion. In addition, studies had to have focused on at least one SDOH domain defined by Healthy People 2030. After screening 1984 articles, 58 articles that evaluated 41 distinct screening tools were selected. Of the 58 articles, 39 (67.2%) targeted populations with CVD, whereas 16 (27.6%) evaluated CVD outcome in non-CVD populations. Three (5.2%) compared SDOH differences between CVD and non-CVD populations. Of 41 screening tools, 24 evaluated multiple SDOH domains and 17 evaluated only 1 domain.

Conclusions: Our review revealed recent interest in SDOH in the field of CVD, with many useful screening tools that can evaluate SDOH. Future studies are needed to clarify the importance of the intervention in SDOH regarding CVD.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of death globally, with the number of deaths from CVD reaching 19.05 million worldwide in 2020,1 representing an 18.7% increase compared with 2010. Of many types of CVD, ischemic heart disease and stroke account for one-third of all deaths worldwide, making CVD a longstanding public health concern and severe global issue.2 Although there have been significant medical advancements in CVD treatment, health disparities remain, and inequitable differences created by various non-medical causes exist.3 These phenomena, collectively called social determinants of health (SDOH), represent a complex interplay between economic, social, political, and cultural factors that significantly influence an individual’s health and wellbeing.4 Emerging evidence suggests that SDOH could be associated with behaviors that increase the risk of CVD, such as smoking and suboptimal nutrition,5,6 particularly among vulnerable populations with limited access to medical care.7

Previous research has highlighted that various SDOH domains, which include healthcare access, socioeconomic status,8 occupation,9 residential environment,10 and education,11 can significantly influence the incidence and risk of CVD, whereas social, cultural, and environmental barriers may exacerbate health inequalities and impede equitable access to medical care. Thus, it is crucial to prioritize disadvantaged and vulnerable populations affected by SDOH for clinical and preventive interventions. Providing personalized care based on SDOH characteristics can benefit these populations and reduce CVD health disparities.12

Although several screening tools for SDOH have been developed,13 clear standards and guidelines on screening and evaluating SDOH remain lacking in the context of CVD. The American Heart Association has recognized the importance of SDOH for heart failure patients, releasing a statement in 2020 that included healthcare frameworks, education, and some screening tools.7 However, the screening tools, including the comprehensive geriatric assessment, frailty phenotype, and deficit accumulation index, primarily evaluate a patient’s function rather than their circumstances. There is no consensus on the systematic evaluation of SDOH screening directly related to CVD, highlighting the need for a comprehensive evaluation. Thus, we aimed to conduct a scoping review for tools to systematically assess SDOH regarding CVD and comprehensively evaluated how these tools could be applied to evaluate SDOH in cardiovascular fields.

We conducted a scoping review that followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1), using the PubMed and Embase databases, on July 25, 2023. The search strategies are described in Supplementary Table 2. This review did not implement a protocol. We included studies focused on screening tools for CVD in alignment with the SDOH definition of Healthy People 2030,14 which serves as an indicator for the national objective of improving the health of people in the US from 2020 to 2030, providing an overarching framework for health policy planning, implementation, and evaluation.14 Previous studies adopted Healthy People 2030’s definition because the main domains of / defined.15–17 Given the lack of a standardized SDOH definition, we used this definition for our assessment.

Flow diagram for the systematic review of screening tools for social determinants of health (SDOH) of cardiovascular disease.

From the initial search (see Supplementary Table 2), we created a database that included author information, article title, abstract, and language of publication. We narrowed down the initial list using the following inclusion criteria: (1) studies that evaluated an SDOH screening tool with CVD outcomes; or (2) studies that explicitly sampled or included participants based on their having CVD. In addition, to be eligible for inclusion in this review, papers had to have focused on at least one SDOH domain of Healthy People 2030.14 These inclusion criteria ensured that all studies had conclusions relevant for the study of CVD and that they used up-to-date methods and understandings of SDOH.

To identify relevant literature, we conducted independent multireviewer screenings of the titles and abstracts of the retrieved citations. Following this initial screening, 2 reviewers evaluated the full text of the eligible articles to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. Once eligible articles were identified, they were grouped into 3 categories based on their relationship between CVD and SDOH. The first category consisted of studies limited to populations with established CVD; the second category included studies that evaluated CVD outcomes in non-CVD patients; and the third category comprised studies that compared SDOH differences between CVD and non-CVD populations. By adopting this categorization approach, we aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the various tools used to assess SDOH and their relationship to CVD in different populations.

Components of SDOH and Definition of VariablesWhile reviewing the eligible articles, we identified a range of screening and assessment tools used to evaluate SDOH regarding CVD. To facilitate an in-depth comparison of these tools, we categorized them according to the 5 primary domains of Healthy People 2030 (Figure 2):18 Economic Stability; Education Access and Quality; Social and Community Context; Health Care Access and Quality; and Neighborhood and Built Environment. These 5 domains were further categorized into subdomains as follows:

Five primary domains of social determinants of health (SDOH) according to the Healthy People 2030 definition, with their subdomains.

• Economic Stability – 4 subdomains: Employment; Food Insecurity; Housing Instability; and Poverty

• Education Access and Quality – 4 subdomains: Early Childhood Development and Education; Enrollment in Higher Education; High School Graduation; and Language and Literacy

• Social and Community Context – 4 subdomains: Civic Participation; Discrimination; Incarceration; and Social Cohesion

• Health Care Access and Quality – 3 subdomains: Access to Health Services; Access to Primary Care; and Health Literacy

• Neighborhood and Built Environment – 4 subdomains: Access to Foods That Support Healthy Dietary Patterns; Crime and Violence; Environmental Conditions; and Quality of Housing.

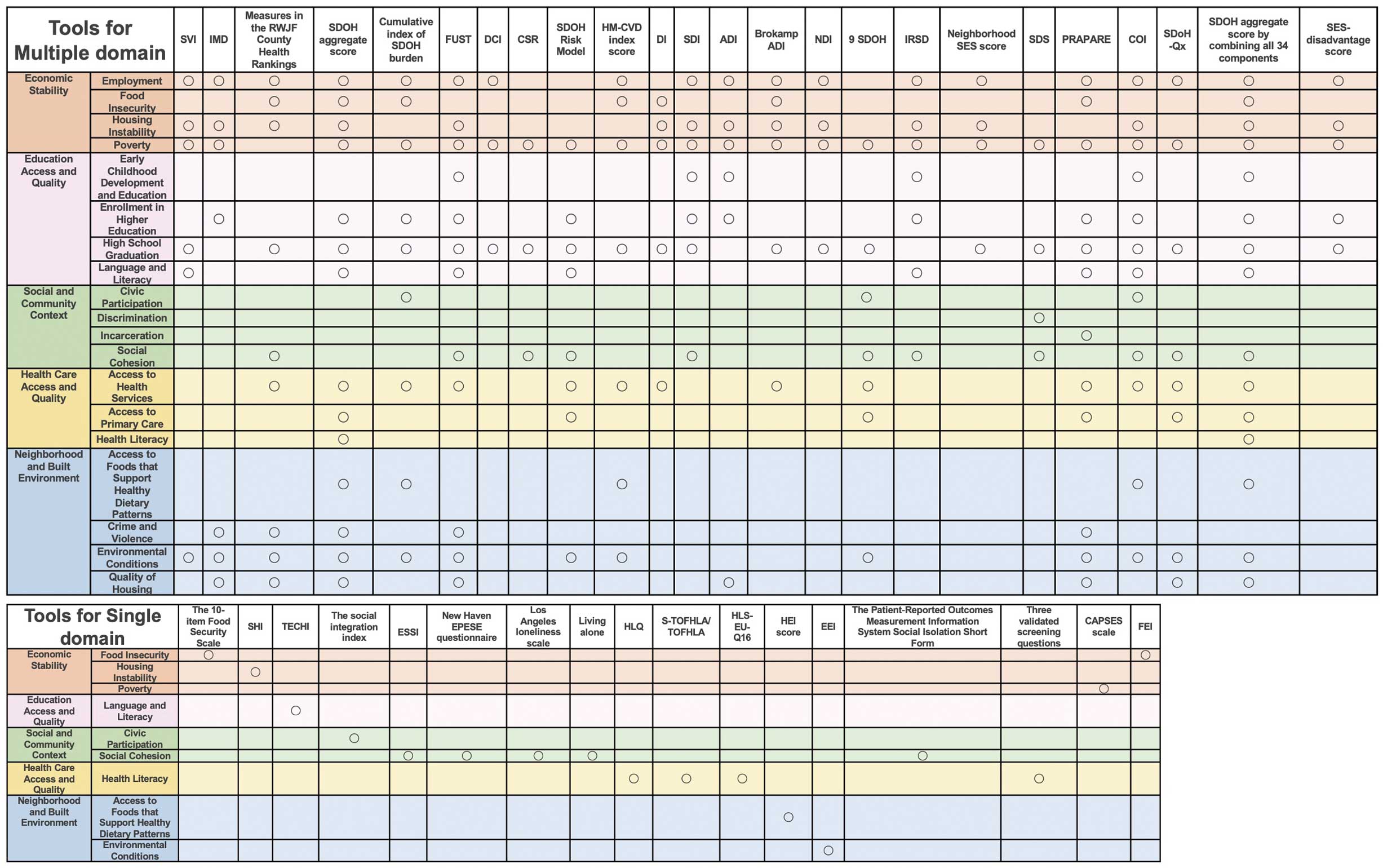

To distinguish among the various assessment tools, we classified them into 2 categories based on the number of domains they evaluated. A tool assessing a single domain was defined as one that evaluates only 1 of the 5 primary domains of SDOH. Conversely, a tool evaluating multiple domains was defined as one that can assess 2 or more primary domains. In addition, we documented the initial year of publication for each extracted tool among the eligible articles (Figure 3).

Time trends of selected tools. The trend of papers reporting social determinants of health (SDOH) tools regarding cardiovascular disease (CVD) has increased over the years. (See Table for definitions.)

Of a potential 1984 articles, 1,770 were excluded based on title and abstract after initial screening and excluding duplicates (Figure 1). A secondary screening of 144 articles ultimately identified 58 articles related to screening tools for SDOH regarding CVD. These 58 articles included 41 unique screening tools for SDOH regarding CVD (Table).8,13,15–17,19–71 Of these 58 articles, 39 (67.2%) included target populations entirely affected by CVD and 16 (27.6%) included target populations that did not initially have CVD, but the evaluated outcome was CVD. Finally, 3 (5.2%) studies evaluated the differences in SDOH between populations with and without CVD. Among these 58 articles, the following CVD were covered: ischemic heart disease (22 article; 37.9%), heart failure (19; 32.8%), and stroke (11; 19.0%). Congenital heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and peripheral arterial disease were the target CVD only in a few articles. Of the 58 articles, only 1 (1.7%) was an intervention trial, with the rest being observational studies. Fifty-six (96.6%) eligible articles were published after 2018 (Figure 3). Regarding first authors, those of 43 (74.1%) articles were from the US, followed by 3 (5.2%) each from the UK, Spain, and Australia, 2 (3.4%) each from Germany and Iran, and 1 (1.7%) each from Brazil and Singapore.

List of Studies Reporting the Use of Social Determinants of Health Screening Tools in the Cardiovascular Field

| Reference | First author |

Year | Tool | Country | Population | Outcome | Sample size |

Design | Brief description of tool |

Brief description of result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First category: CVD population | ||||||||||

| 20 | Witte | 2018 | IMD | UK | HF | Death, hospitalization |

1,802 | Cohort study | IMD is an index measuring socioeconomic deprivation using data from various UK sources IMD is a recognized indicator of geographical deprivation and a valuable tool for health research |

IMD score was associated with the risk of age- and sex-adjusted all-cause mortality, and non-CV mortality |

| 21 | Lawson | 2020 | IMD | UK | HF | Ischemic coronary events, risk factors |

108,638 | Cohort study | See above | The most deprived had higher annual increases in comorbidity numbers than the most affluent |

| 23 | Khan | 2022 | SDOH aggregate score |

US | Partially CVD (stroke) |

Stroke | 123,631 | Cross-sectional study |

An SDOH aggregate score was derived from 39 subcomponents across 5 domains (economic stability, neighborhood, community and social context, food, education, and health care system access) and divided into quartiles |

Almost 50% of non-elderly people who have had a stroke have an unfavorable SDOH profile |

| 24 | Hagan | 2021 | Cumulative index of SDOH burden |

US | CVD (heart disease, heart attack, or stroke) |

COVID-19 | 25,269 | Cross-sectional study |

A cumulative index of SDOH burden includes education, insurance, economic stability, 30-day food security, urbanicity, neighborhood quality, and integration |

SDOH burden is associated with lower COVID-19 risk mitigation practices in the CVD population |

| 25 | Neadley | 2021 | FUST | Australia | Partially CVD (HF) |

NA | 37 | Cohort study | FUST collects data on sociodemographic status, employment, housing stability, Internet use, social support, difficulties seeking medical care and exposure to abuse and stress |

This study population reported a substantial burden of a range of adverse SDOH |

| 26 | Hawkins | 2019 | DCI | US | PAD | MALEs | 2,578 | Cohort study | The DCI score (from 0 to 100) estimates socioeconomic distress of a community at the zip code level |

Severely distressed communities had increased rates of MALEs |

| 27 | Patel | 2020 | CSR | US | MI | Silent MI mortality |

6,708 | Cross-sectional study |

The CSR (0 to ≥3) was calculated by the number of baseline social risk factors (minority race, poverty- income ratio <1, education <12th grade, and living single) |

The CSR is associated with increased risk of silent MI |

| 28 | Canterbury | 2020 | CSR | US | MI, coronary revascularization, HF, stroke |

All-cause mortality, non-fatal CVD events (non-fatal MI, stroke, coronary revascularization) |

1,933 | Cohort study | See above | The association of increasing CSR with higher CVD and mortality risks is partially accounted for by exposure to PM2.5 environmental pollutants |

| 30 | de Loizaga | 2022 | DI | US | CHD | 1-year mortality | 974 | Cohort study | The DI is calculated using 6 factors from the 2015 American Community Survey: population below poverty level, median household income, education level, health insurance, households getting public assistance or food stamps, and vacant houses |

The DI was associated with death among infants with single ventricle heart disease in the first year of life |

| 32 | Garcia | 2018 | SDI | Spain | HF | Hospitalization, mortality |

8,235 | Cohort study | SDI includes unemployment, percentage of manual and temporary workers, and population with insufficient education |

Socioeconomic deprivation was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization |

| 33 | Patel | 2020 | SDI | US | HF | 30-days readmission (HF) |

30,630 | Cohort study | See above | Black patients face higher 30-day HF readmissions and mortality, and it worsens with increasing SDI |

| 35 | Knighton | 2018 | ADI | US | HF | 30-day mortality/ readmission (HF) |

4,737 | Cohort study | ADI includes 17 indicators of material and social conditions, including income, education level, employment status, and housing security |

For HF patients from deprived areas, identifying with a faith reduced the 30-day mortality odds by one-third vs. those without a faith |

| 36 | Johnson | 2021 | ADI | US | HF, MI, AF | 30-day and 1-year readmission and mortality |

27,694 | Cohort study | See above | Residence in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities predicts rehospitalization and mortality |

| 37 | Berman | 2021 | ADI | US | MI | All-cause mortality/CV death |

2,097 | Cohort study | See above | Living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods was associated with higher all-cause and CV mortality |

| 38 | Phillips | 2022 | ADI | US | Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture |

EVAR or open repair |

632 | Cohort study | See above | Living in highly deprived areas increased the likelihood of presenting under age 65 and having an open repair |

| 39 | Kostelanetz | 2021 | Brokamp ADI | US | ACS, HF | All-cause mortality |

2,998 | Cohort study | The Brokamp ADI uses 6 census tract level variables derived from the 2015 5-year American Community Survey |

The Brokamp ADI is associated with mortality in hospitalized CVD patients |

| 15 | Sterling | 2022 | 9 SDOH | US | HF | CVD incidence and readmission |

690 | Cohort study | 9 SDOH based on the Healthy People 2030 framework: race, education, income, social isolation, social network, residential poverty, health professional shortage area, rural residence, and state public health infrastructure |

None of the SDOH was associated with 30-day readmission |

| 41 | Biswas | 2019 | IRSD | Australia | STEMI | 12-month MACE |

5,655 | Cohort study | Patients were categorized into SES quintiles using the IRSD system, a score allocated to each residential postcode based on factors like income, education level, and employment status |

Lower SES patients have more comorbidities and experienced slightly longer reperfusion times |

| 42 | Kang | 2021 | IRSD | Australia | RHD | Incidence of RHD, hospitalization |

686 | Cohort study | See above | There was an inverse correlation between the community socioeconomic index and the prevalence of RHD |

| 43 | Udell | 2018 | Neighborhood SES score |

US | MI | In-hospital mortality/MACE |

390,692 | Cohort study | Neighborhood SES score combines data on local wealth/income, education, and occupation |

Patients from the most disadvantaged neighborhoods received similar in-hospital care as those from advantaged areas but faced delays in angiography They also had a higher risk of adverse in-hospital outcomes, including mortality, after AMI |

| 45 | Baker- Smith |

2021 | TECHI | US | Parents of children with heart disease |

Ability to deal with technology matters |

849 | Cohort study | TECHI measures how often and comfortably someone uses technology daily and how capable they feel in handling technology-based issues |

A determinant of telehealth acceptance was digital literacy |

| 47 | Raparelli | 2021 | ESSI | US/Canada | ACS | Quality of in-hospital care, readmission |

4,048 | Cohort study | Low social support was defined as a score of ≤3 on at least 2 ESSI items and a total ESSI score of ≤18 |

Healthcare systems and SDOH that depict social vulnerability are associated with quality of AMI care |

| 51 | Ho | 2023 | SHI | Singapore | OHCA (partially CVD) |

Receipt of bystander CPR and survival to discharge |

12,730 | Cohort study | The SHI is a building-level index of socioeconomic status. |

Lower building-level socioeconomic status was associated with lower rate of bystander CPR |

| 52 | Chehuen | 2019 | S-TOFHLA | Brazil | Chronic CVD | Functional HL | 351 | Cross-sectional study |

The S-TOFHLA is a functional HL test for adults, scored out of a maximum of 100 points Scores are categorized into 3 levels |

Inadequate functional HL was associated with impaired understanding of the disease and medical instructions |

| 54 | Cabellos- García |

2021 | HLQ | Spain | Anticoagulation user (AF, valve replacement) |

Anticoagulant treatment, emergency care visits and unscheduled hospital admissions |

252 | Cross-sectional study |

The HLQ measures HL levels using 44 items across 9 dimensions |

HL significantly affects proper self-management of anticoagulation therapy and the occurrence of complications |

| 55 | Cabellos- García |

2020 | HLQ | Spain | AF, valvular disease |

Literacy | 252 | Cross-sectional study |

See above | Level of education and social class were social determinants associated with HL scores |

| 57 | Tavakoly Seyedeh |

2019 | TOFHLA | Iran | HF | HL | 80 | RCT | The large version of American TOFHLA is a reliable and valid measure in the healthcare concepts and includes 2 parts: numeric and reading comprehension |

HF patients with adequate HL were younger and had higher levels of educational attainment |

| 58 | Savitz | 2023 | Three validated screening questions/ADI/ the PROMIS® Social Isolation Short Form |

US | HF | All-cause ED visits and hospitalizations |

3,142 | Cohort study | Health literacy was measured using 3 validated screening tools and categorized into adequate or inadequate HL Social isolation was measured using the PROMIS® Social Isolation Short Form 4a v2.034 and categorized into low, moderate, or high social isolation |

Education, social isolation, and ADI were association with HF hospitalizations |

| 59 | Suarez- Pierre |

2023 | SVI | US | Adult heart recipients after heart transplantation |

All-cause mortality | 23,700 | Cohort study | The SVI uses US census data to determine the social vulnerability of every census tract based on 15 factors |

People living in vulnerable communities may be at elevated risk of all-cause mortality after heart transplantation |

| 60 | Hammoud | 2023 | SDS | US | Subclinical CVD | ASCVD, all-cause mortality |

6,434 | Cohort study | The SDS (from 0 to 4), was calculated by the following factors: household income less than the federal poverty level; educational attainment less than a high school diploma; single living status; and experience of lifetime discrimination |

The SDS was associated with incident ASCVD and all-cause mortality |

| 61 | Schenck | 2023 | DCI | US | PAD | Mortality and major amputation |

16,864 | Cohort study | See above | High DCI is associated with elevated risk of all- cause mortality and major amputation after peripheral vascular intervention |

| 16 | Osei | 2023 | PRAPARE | US | HF | Self-care | 104 | Cross-sectional study |

The PRAPARE is a 21-item instrument with 17 items representing 4 core SDOH domains that align with Healthy People 2020 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention fs agenda for prioritizing SDOH in health centers |

Several SDOH variables affect HF self-care |

| 62 | Mayourian | 2023 | COI | US | Children under 18 years of age who underwent cardiac surgery |

Hospital discharge, readmission, and all-cause mortality |

6,247 | Cohort study | The COI 2.0 includes 29 variables in 3 domains of neighborhood opportunity: educational, health/environmental, and social/economic |

Lower COI was associated with longer hospital lengths of stay and an increased risk of death |

| 63 | Asadi-Lari | 2023 | CAPSES scale |

Iran | Partially CVD | CVD (AMI and stroke) |

91,830 | Cross-sectional study |

The CAPSES scale is a composite indicator that includes more social complexities in the socioeconomic status than traditional indicators |

The CAPSES scale was significantly associated with stroke |

| 64 | Robbins | 2023 | SVI | US | Peripartum cardiomyopathy |

Living in communities with greater social vulnerability |

90 | Cohort study | See above | Individuals who experienced more severe outcomes of peripartum cardiomyopathy were found to live in higher SVI communities |

| 65 | Valero- Elizondo |

2022 | SDOH aggregate score by combining all 34 components |

US | ASCVD | Financial toxicity | 164,696 | Cross-sectional study |

The SDOH components from the Kaiser Family Foundation define 6 domains: economic stability, neighborhood, community and social context, food poverty, education, and access to healthcare |

An unfavorable SDOH profile was associated with subjective financial toxicity from healthcare |

| 66 | Rao | 2022 | SES – disadvantage score |

US | HF | All-cause in-hospital mortality |

321,314 | Cohort study | SES – disadvantage scores were calculated from geocoded US census data using a validated algorithm, which incorporated household income, home value, rent, education, and employment |

SES disadvantage was associated with higher in-hospital mortality |

| 67 | Thompson | 2022 | SVI | US | ASCVD | Healthcare access | 203,347 | Cross-sectional study |

See above | The SVI was associated with healthcare access in individuals with pre-existing ASCVD |

| 68 | Jain | 2022 | SVI | US | ASCVD | CV comorbidities | 1,745,999 | Cohort study | See above | The SVI was associated with prevalent CV comorbidities and ASCVD |

| Second category: Non-CVD population, CVD outcome | ||||||||||

| 8 | Bevan | 2023 | SVI | US | Non-CVD (county level) |

CAD | 2,173 | Cross-sectional study |

See above | SES and household composition and/or disability were the SVI themes most closely associated with CAD prevalence |

| 13 | Hong | 2020 | HM-CVD index score |

US | Non-CVD (county level) |

Mortality rate for all CVD |

3,026 | Cross-sectional study |

The HM-CVD index comprises 7 factors: minority race percentage, family poverty rate, low high school diploma percentage, grocery store and fast-food ratios, post-tax soda price, and primary care physicians density Higher scores indicate increased CVD burden |

The HM-CVD index can accurately classify counties with high CVD burden |

| 19 | Wild | 2022 | SVI | US | Non-CVD (county level) |

CVD (heart disease, AMI) and risks |

64 | Ecological study |

See above | The SVI explained a significant proportion of variability in hospitalizations for heart disease and MIs |

| 29 | Hammond | 2020 | SDOH Risk Model |

US | Non-CVD | CVD prediction modeling (all-cause hospitalization, CV hospitalization) |

3,614 | Cohort study | SDOH Risk Model includes the 7 core SDOH domains: rural vs. urban residence, alcohol abuse, access to care, economic status, financial strain, social support, and education |

Adding SDOH Risk Model improved model accuracy for hospitalization, death, and costs of care among racial and ethnic minorities in a large, nationally representative cohort of older US adults |

| 31 | de Loizaga | 2021 | DI | US | Non-CVD | RHD | 947 | Cohort study | See above | Higher DI was associated with increasing disease severity |

| 40 | Akwo | 2018 | NDI | US | Non-CVD | HF | 26,818 | Cohort study | NDI combines social and economic indicators that indicate neighborhood deprivation and are associated with negative health outcomes; these indicators include social factors, wealth/income, education, and occupation |

Among economically disadvantaged individuals, the lack of community resources further increases the HF risk, above and beyond individual SES and conventional CV risk factors |

| 44 | Palakshappa | 2019 | The 10-Item Food Security Scale |

US | Non-CVD | Comorbidities (CAD, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, congestive HF, stroke, asthma, and obesity-associated cancers) |

9,203 | Cross-sectional study |

Household FI was assessed using the US Department of Agriculture fs 10-item Food Security Scale Households are categorized based on affirmative responses: high, marginal, low, and very low food security |

FI was associated with increased odds of CAD |

| 48 | Gronewold | 2020 | New Haven EPESE questionnaire/ social integration index |

Germany | Non-CVD | CV event (strokes, coronary events or independently coded causes of deaths according to diseases of the circulatory system) |

4,139 | Cohort study | The New Haven EPESE is a tool for evaluating instrumental and emotional social support, allowing the categorization of the need for support into 4 categories |

Perceiving a lack of financial support was associated with higher CV event incidence; being socially isolated was associated with increased all-cause mortality |

| 49 | Bu | 2020 | Los Angeles loneliness scale |

UK | Non-CVD | CVD diagnosis or admission (angina, Heart attack, congestive HF, heart murmur, abnormal heart rhythm, stroke and other heart disease) |

4,279 | Cohort study | The Los Angeles loneliness scale includes the 3 questions Responses to each question were scored on a 3-point Likert scale Using the sum score, we can get a loneliness scale ranging from 3 to 9, with a higher score indicating increased loneliness |

Loneliness was associated with an increased risk of CVD events independent of potential confounders and risk factors |

| 50 | Lee | 2021 | Living alone | US | Non-CVD | All-cause mortality (partially CVD) |

388,973 | Cohort study | Respondents reporting living alone for the family structure variable were categorized as living alone Living alone has been widely used as an objective measure of social isolation in empirical research |

People experiencing social isolation had statistically significantly higher relative risks of all-cause and heart disease mortality in the US than people living with others |

| 53 | Tiller | 2015 | HLS-EU-Q16 | Germany | Non-CVD | Diabetes, MI, stroke | 1,107 | Cohort study | HLD-EU is a questionnaire to measure HL in the general population; the short version of the HLS-EU questionnaire is the HLS-EU-Q16 |

An inverse association was observed between HL and MI among women, and between HL and stroke among men |

| 56 | Yu | 2015 | HEI score | US | Non-CVD | CVD mortality (partially) |

84,735 | Cohort study | HEI comprises 12 components with a total score of 100 points, with higher scores suggesting higher guideline adherence and a better-quality diet |

A higher HEI score was associated with lower risks of disease death |

| 69 | Mentias | 2023 | SDI | US | Non-CVD | HF | 2,388,955 | Cohort study | The SDI is a combined assessment of deprivation at the zip code level, considering 7 demographic factors, including poverty rate, education, employment, housing, household attributes, and transportation access |

In socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, the relationship between redlining and HF is pronounced |

| 70 | Shaik | 2023 | SVI | US | Non-CVD (county level) |

AMI related to age-adjusted mortality rate |

2,908 | Ecological study | See above | Counties in the US with higher SVI scores showed greater age-adjusted mortality related to AMI than counties with lower SVI scores |

| 17 | Javed | 2023 | SdoH-Qx | US | Non-CVD | All-cause and CVD mortality |

252,218 | Cohort study | The SdoH-Qx consists of the organization of 14 SDOH into 5 domains based on the SDOH framework suggested by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Healthy People 2030: economic stability, neighborhood, physical environment, and social cohesion, community and social context, education, and healthcare system |

The higher SDOH burden is associated with up to a nearly 3-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality |

| 71 | Gondi | 2022 | FEI | US | Non-CVD (county level) |

HF mortality | 3,147 | Cross-sectional study |

FEI, a standardized scale from 0 to 10 designed to be a comprehensive metric of whether a locality is a food desert, encompassing multiple metrics of the food environment, including food access, food security, proximity to stores, income, and local geographic and socioeconomic factors |

A healthier food environment is associated with lower HF mortality |

| Third category: Comparison between CVD and non-CVD populations | ||||||||||

| 22 | Wang | 2020 | Measures in the RWJF County Health Rankings |

US | Ischemic stroke (CVD and non-CVD, county level) |

NA | 6,642,946 | Cross-sectional study |

RWJF data were used to create characteristics at the county level that captured the 6 key domains of the SDOH (economic stability, neighborhood and physical environment, education status, food access, social and community context, healthcare) |

Air pollution exceeding the national median, percentage of children in single-parent households exceeding the national median, violent crime rates exceeding the national median, and percentage smoking exceeding the national median were associated with ischemic stroke hospitalizations |

| 34 | Peyvandi | 2020 | SDI/EEI | US | CHD vs. non-CHD |

Having significant CHD |

7,698 | Cohort study | For SDI, see above The EEI included levels of exposure to the following pollutants in each census tract: toxic release from facilities; air quality measured by ozone (main ingredient in smog) and PM2.5; drinking water contaminants; and pollution from diesel engines/exhaust |

Increased social deprivation and exposure to environmental pollutants are associated with the incidence of live-born CHD |

| 46 | Mahajan | 2021 | Validated 10-item US Adult Food Security Survey Module |

US | ASCVD vs. non-ASCVD (CAD or stroke) |

Food insecurity and sociodemographic characteristics |

190,113 | Cross-sectional study |

Food security was measured using a validated 10-item US Adult Food Security Survey Module, which assesses the frequency with which each household/adult reported food insecurity in the past 30 days Each survey question was scored as “1” if reported to be “yes”; scores were then summed to a potential maximum of 10 |

Among adults with ASCVD, 14.6% reported experiencing food insecurity, which was significantly higher than the 9.1% observed among those without ASCVD |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ADI, Area Deprivation Index; AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHD, Congenital heart disease; COI, Child Opportunity Index; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CSR, Cumulative Social Risk; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DCI, Distressed Communities Index; DI, Deprivation Index; ED, emergency department; EEI, Environmental Exposure Index; ESSI, ENRICHD (Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease) Social Support Instrument; EVAR, endovascular aortic repair; FEI, Food Environment Index; FI, food insecurity; FUST, Flinders University Social Health History Screening; HEI, Healthy Eating Index; HF, heart failure; HL, health literacy; HLQ, Health Literacy Questionnaire; HLS-EU-Q16, 16-item European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire; HM-CVD, Hong-ainous Cardiovascular Disease; IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation; IRSD, Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MALEs, major adverse limb events; MI, myocardial infarction; NDI, Neighborhood Deprivation Index; New Haven EPESE, New Haven Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PRAPARE, Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences; PROMIS®, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; RCT, randomized control trial; RHD, rheumatic heart disease; RWJF, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; S-TOFHLA, Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults – Short Form; SDI, Social Deprivation Index; SDOH, social determinant of health; SdoH-Qx, SDOH burden divided into quintiles; SDS, Social Disadvantage Score; SES, socioeconomic status; SHI, Singapore Housing Index; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; SVI, Social Vulnerability Index; TECHI, Technological Ease and Computer-based Habits Inventory; a composite socioeconomic status indicator containing material capital, human capital, and social capital, CAPSES.

Among the 41 unique tools, 24 assessed multiple domains and 17 assessed a single domain (Figure 4). Among the 24 tools assessing multiple domains, 9 (37.5%) could evaluate all primary domains of the SDOH simultaneously. These 9 tools were: measures in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation County Health Rankings;22 a cumulative index of SDOH burden;24 the Flinders University Social Health History Screening Tool (FUST);25 the SDOH risk model;29 9 SDOH;15 the Social Disadvantage Score (SDS);60 the Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE);16 the Child Opportunity Index (COI);62 the SDOH burden divided into quintiles (SDoH-Qx);17 an SDOH aggregate score by combining all 34 components;65 and the socioeconomic status (SES) disadvantage score.66 The evaluation items for each tool are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

Distribution of social determinants of health domains for each tool. Abbrevitions as in Table.

Economic Stability

Economic Stability was the sole focus of 4 (23.5%) studies using single-domain tools. Among these studies, the subdomain Food Insecurity was evaluated by the 10-item Food Insecurity Scale and the Food Environment Index (FEI). Housing Instability and Poverty were assessed by the Singapore Housing Index (SHI) and a composite socioeconomic status indicator containing material capital, human capital, and social capital (CAPSES) scale, respectively.

Economic Stability could be assessed in all 24 (100%) multiple-domain tools. Among them, the subdomains Employment, Food Insecurity, Housing Instability, and Poverty could be assessed in 20 (83.3%), 8 (33.3%), 15 (62.5%), and 23 (95.8%) tools, respectively (Table).

Education Access and QualityAmong tools for a single domain, only the Technological Ease and Computer-Based Habits Inventory (TECHI) was used to evaluate the Language and Literacy subdomain and to self-assess the frequency and ability to use technology in daily life and the ability to cope with problems using technology.

Education Access and Quality could be evaluated by all 24 (100%) multiple-domain tools. Among the tools, the subdomains Early Childhood Development and Education, Enrollment in Higher Education, High School Graduation, and Language and Literacy could be assessed in 6 (25.0%), 12 (50.0%), 21 (87.5%), and 8 (33.3%) tools, respectively.

Social and Community ContextAmong tools evaluating a single domain that examined Social and Community Context, the subdomain Civic Participation was evaluated by the Social Integration Index developed by Berkman.72 Social Cohesion could be assessed by 5 (29.4%) single-domain tools, namely the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) Social Support Instrument (ESSI); the New Haven Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (New Haven EPESE) questionnaire; the Los Angeles loneliness scale; the living alone; and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Social Isolation Short Form. We could not find single-domain tools that evaluated the Discrimination and Incarceration subdomains.

Social and Community Context was evaluated by 13 (54.2%) multiple-domain tools. Among the tools evaluating Social and Community Context, 3 (12.5%), 1 (4.2%), 1 (4.2%), and 11 (45.8%) tools assessed Civic Participation, Discrimination, Incarceration, and Social Cohesion, respectively.

Health Care Access and QualityAmong single-domain tools, only the Health Literacy subdomain of the Health Care Access and Quality domain was evaluated by 4 (23.5%) tools: the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ), the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), the 16-item European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q16), and three validated screening questions.

Health Care Access and Quality was evaluated by 13 (54.2%) multiple-domain tools. Among the tools, 13 (54.2%), 5 (20.8%), and 2 (8.3%) tools assessed Access to Health Services, Access to Primary Care, and Health Literacy, respectively.

Neighborhood and Built EnvironmentAmong tools evaluating a single domain that focused on Neighborhood and Built Environment, the Access to Foods That Support Healthy Dietary Patterns and Environmental Conditions subdomains were evaluated by the Healthy Eating Index and Environmental Exposure Index, respectively.

The Neighborhood and Built Environment domain was evaluated by 14 (58.3%) multiple-domain tools. Among these tools, 5 (20.8%), 5 (20.8%), 13 (54.2%), and 8 (33.3%) tools assessed Access to Foods That Support Healthy Dietary Patterns, Crime and Violence, Environmental Conditions, and Quality of Housing, respectively.

This review is the first scoping review to investigate tools for assessing or screening SDOH at the individual and population levels in the cardiovascular field, with 17 tools focusing on a single domain of SDOH and 24 focusing on multiple domains. This study has 2 major findings. First, most of the eligible articles were published after 2018, which may imply increasing recent attention to SDOH in the field of CVD. This is important because additional screening tools will likely be developed, and their uses better understood over time. Second, no single tool could cover all subdomains; researchers interested in studying SDOH for CVD will need to compare the various tools and identify which subdomain/s is/are less pertinent to their research.

Recently, the importance of SDOH has gained widespread attention because a large proportion of health outcomes stems not only from clinical care, but also from socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and the physical environment. Our research revealed that of the 58 articles related to SDOH screening tools regarding CVD, only 1 was an intervention trial, with the rest all non-interventional studies. Therefore, it can be said that there is not sufficient evidence to broadly recommend interventions for SDOH for CVD. There is diversity within SDOH variables and complex interactions and feedback loops among these determinants, so comprehensively evaluating and intervening is not straightforward.73 Although our study demonstrated that most of the studies were conducted in the US, there is no uniform opinion as to when and where screening should or should not be conducted even in the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).74 Screening and addressing SDOH require understanding available social systems, local resources, and welfare services.75 In addition, any screening tool should be easy to use in the clinical setting and capable of addressing specific regional needs, and effectively identify the unique needs that organizations can address.76 Each country will likely need to continue evaluating the accumulation of evidence and possible interventions, particularly in the case of SDOH screening and interventions in cardiovascular care, where sufficient evidence has not yet been accumulated. There will likely be a need for future clinical research and societal implementation programs to address this area of significant public health concern.77

Our review illustrates that numerous screening tools are available for assessing SDOH regarding CVD; however, there is currently no single comprehensive or one-size-fits-all tool. This lack of a standardized tool can be attributed to variations in SDOH components across countries and systems, because there is no consensus about the framework and categories of SDOH. For instance, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) divides SDOH into 6 domains with subdomains, whereas the World Health Organization (WHO) provides a conceptual SDOH model that includes structural and intermediary determinants.4,78 In comparison, Healthy People 2030, which we used in our review, clearly identifies 5 domains and their subdomains, each of which is clearly defined.14 However, even within the framework of Healthy People 2030, there are variations in concepts across domains, such as transportation and parks in the Neighborhood and Physical Environment domain of the KFF. Furthermore, an additional important perspective is that the significance of SDOH regarding CVD may differ from its significance in public health policies.79 Addressing disparities in SDOH is not something that can be resolved solely at the micro level of individual doctors or medical institutions. In most cases, an approach from a macro perspective that goes beyond medical institutions, such as collaborating with the community and through policies, is necessary.80 Therefore, it is inferred that the way SDOH is perceived and its importance may vary between clinical settings and public health policy arenas. This difference in perspective is an essential factor to consider when discussing its definition. Given the different needs and viewpoints on SDOH across the world, and even within a country, it is natural to have differences in categories of SDOH, which can result in variations in screening tools. Although a consensus on SDOH domains would be beneficial for research purposes, the definition and categorization of SDOH could be better developed locally to account for practical considerations. Further discussions are necessary to reach a consensus on the framework and categories of SDOH, which would help standardize the screening and intervention process. This review shows that despite a consensus that SDOH should be evaluated and acted on concerning CVD, no existing tools are perfectly suited for the task. So, this is something that the field of CVD should focus on as SDOH becomes an ever more important focus of CVD.

This review has several limitations. First, on the basis of the articles included in the review, it is predominantly representative of the US and includes highly region-specific items, such as the Area Deprivation Index, so future evaluation of external validity in other countries is required. Second, although each screening tool has been validated in each country’s language, most of the tools are written in English, so it is necessary to set up a validated tool that considers language differences to use these tools in one’s own country. Third, our review mainly focused on CVD, not other related conditions or risk factors. The applicability of relevant tools to other related cardiovascular conditions, such as hypertension, was not evaluated in studies included herein, so further evidence needs to be accumulated. Furthermore, we have classified and evaluated the domains of SDOH according to Healthy People 2030. Currently, there is no universally standardized definition for SDOH. Although we have adopted the Healthy People 2030 definition, it is essential to remain attentive to the potential for other definitions and the evolving nature of future definitions. In addition, in our current search, the term “Social Determinants of Health” exists as a Mesh term. Therefore, we conducted our search based on that Mesh word, adopting a search formula that comprehensively includes all studies in which the authors have reported including the concept of SDOH. Consequently, there is a limitation that we may not have been able to fully capture studies related to the downstream concepts executed without the authors being aware of SDOH. However, it is hard to say that the concept of SDOH is fully established yet, so we believe there is significance in limiting our evaluation to only those studies that report including the SDOH concept.

In conclusion, our review revealed recent interest in SDOH in the cardiovascular field and there were some useful screening or assessment tools that could evaluate the 5 main domains of SDOH. Future studies will be needed to clarify the importance of the intervention about SDOH screening on outcome.

None.

This study did not receive any specific funding.

The authors report no conflicts of interest. J.R.’s affiliation with MITRE Corporation is for identification only, and does not imply MITRE’s concurrence with the authors’ views.

T.S. wrote the manuscript draft. A.M. supervised this study. T.S. and A.M. participated in the literature review. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it.

The Institutional Review Board of St. Luke’s International Hospital decided that the study did not need ethics approval.

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-23-0443