Article ID: CJ-17-1340

Article ID: CJ-17-1340

Background: The hospital mortality rate in >80-year-old patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is reportedly satisfactory, but how such patients’ functional status both at discharge and during the postoperative hospitalization period might affect their quality of life and medical costs remains unclear.

Methods and Results: The adverse events of 161 patients aged >80 years who underwent SAVR with or without coronary artery bypass grafting were retrospectively investigated. Adverse events were defined as hospital death, a long hospital stay (>60 days) attributable to major complications or requirement for rehabilitation, or a depressed status at discharge (modified Rankin scale score >4). A total of 18.6% of patients developed adverse events, and their hospital mortality rate was 4.3%. Logistic regression analysis revealed that a perfusion time >3 h (P=0.0331; odds ratio, 2.685) and EuroSCORE II >10% (P<0.0001; odds ratio, 8.232) were significant risk factors for adverse events. The average medical cost was approximately 1.5-fold higher in patients with adverse events (¥8,360,880 vs. ¥5,234,660, P=0.0016).

Conclusions: Clinical findings focusing on status at discharge and during postoperative hospitalization of SAVR in patients aged >80 years was relatively high compared with hospital mortality, especially in patients with a longer perfusion time and high EuroSCORE. Further studies are necessary to define the indications for SAVR in patients aged >80 years in the era of transcatheter AVR.

In Japan’s aging society, increasing numbers of patients, especially those with valvular disease, are being referred for cardiovascular surgery.1 Aortic valve surgery for aortic stenosis (AS) accounts for many valve surgeries performed in patients aged >80 years. AS is a life-threatening disease, and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) is the most effective and promising therapy for severe AS. The clinical results of SAVR are reportedly satisfactory, even in octogenarians, when a surgical candidate with a relatively low risk score is appropriately selected.2–6 However, elderly patients generally have a variety of surgical risk factors, and studies have shown that approximately 30–40% of symptomatic patients with critical AS are not referred for SAVR.7,8 Recent advances have been made in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), and this technique has been proposed as an alternative treatment modality for patients who are ineligible or at very high risk for AVR.9,10 TAVR has shown excellent results in patients with high risk scores or contraindications for surgery, such as a porcelain aorta.9 However, TAVR lacks both durability and long-term survival benefits in patients with extensive coexisting morbidities.9 Considering the increasing average life expectancy, a prosthetic valve with longer durability is needed.

Selection of TAVR or SAVR for elderly patients with severe AS should be based on consideration of various factors, including the patient’s life expectancy and the short- and long-term clinical outcomes of both procedures. The patient’s postoperative activity of daily living (ADL) is one of these concerns. Compared with younger patients, cardiac surgery in elderly patients can have a higher risk of postoperative deterioration in ADL. Considering the short life expectancy of octogenarians, a longer hospital stay or postoperative rehabilitation in patients with a compromised general condition might result in impaired quality of daily life (QOL). The risk factors for impairment of postoperative QOL have not been fully addressed, but such an investigation is warranted. In addition, medical costs are increasing because of the rapidly escalating healthcare costs in an aging society. Therefore, an appropriate balance of the clinical and financial outcomes of such procedures should be addressed.

In the present study, we investigated the functional status at discharge and during the postoperative hospitalization period in addition to hospital mortality, later clinical outcomes, and medical costs in patients aged >80 years undergoing SAVR.

From 2008 to 2011, 1,683 consecutive cases of SAVR with or without coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were performed at Osaka University and its 22 associated facilities (Osaka Cardiovascular Surgery Research Group [OSCAR]). Among the patients who underwent these procedures, we retrospectively reviewed 161 patients with AS aged ≥80 years (503 patients aged <80 years) whose medical information was available. The patients’ preoperative characteristics are listed in Table 1; 50 (31.1%) patients were >85 years old; 8 (5.0%) patients were hemodialysis-dependent, and 47 (29.2%) patients had a creatinine clearance rate <30 mL/min; 10 (6.2%) patients had moderate or severe chronic obstructive lung disease, 26 (16.1%) had ≥2 diseased coronary arteries, 57 (35.4%) had a New York Heart Association (NYHA) class ≥3, and 7 (4.3%) had a history of previous cardiac surgery. Urgent or emergency surgery was performed in 5 (3.1%) patients. Combined CABG was performed in 47 (29.2%) patients, and the perfusion time was >3 h in 35 (21.7%) patients. The logistic EuroSCORE, EuroSCORE II, and STS scores were 12.9±7.9, 4.7±3.2, and 6.9±5.1%, respectively. In total, 12%, 7% and 14% of patients had a logistic EuroSCORE >20%, EuroSCORE II >10% and STS score >10%, respectively. This study was retrospective study and was approved by the institutional review board.

| SAVR (n=161) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age >85 years | 50 (31.1%) | NYHA >3 | 57 (35.4%) | |

| BMI >26 | 20 (12.4%) | HF | 42 (26.1%) | |

| Current smoker | 13 (8.1%) | Cardiogenic shock | 1 (0.6%) | |

| DM | 28 (17.4%) | LV function bad | 5 (3.1%) | |

| CLCr <30 | 47 (29.2%) | CCS >3 | 11 (6.8%) | |

| HD | 8 (5.0%) | History of CVS op | 7 (4.3%) | |

| Carotid stenosis | 10 (6.2%) | History of valve op. | 6 (3.7%) | |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 14 (8.7%) | Urgency | 5 (3.1%) | |

| History of CVD | 7 (4.3%) | Combined CABG | 47 (29.2%) | |

| COPD >moderate | 10 (6.2%) | Op time >6 h | 51 (31.7%) | |

| Arrhythmia | 19 (11.8%) | Perfusion time >3 h | 35 (21.7%) | |

| AMI | 2 (1.2%) | Logistic Euro | 12.9±7.9% | |

| AP | 30 (18.6%) | Euro II | 4.7±3.2% | |

| Active IE | 3 (1.9%) | STS score | 6.9±5.1% | |

| No. of diseased coronary vessels >2 |

26 (16.1%) | Valve type | ||

| MR >3 | 7 (4.3%) | Bioprosthesis | 151 (93.7%) | |

| TR >3 | 4 (2.5%) | Mechanical | 10 (6.2%) | |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AP, angina pectoris; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; CLCr, creatine clearance; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; CVS, cardiovascular surgery; DM, diabetes mellitus; HD, hemodialysis; HF, heart failure; IE, infective endocarditis; LV, left ventricle; MR, mitral regurgitation; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

The definitions used in the present study are almost identical to those established by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) National Database. These definitions are available online at http://sts.org. Adverse events (AEs) were defined as any ≥1 of the following: death during hospitalization, a long hospital stay (>60 days) attributable to a major complication or requirement for rehabilitation, or a depressed status at discharge (modified Rankin scale score >4: unable to walk without assistance and unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance).

Statistical AnalysisVariables are expressed as mean±standard deviation or percentage. Univariate analysis was performed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Statistically significant variables from the univariate analysis (P<0.2) were subjected to multivariate analysis using a Cox binary logistic regression model. Statistical significance was assumed for P values of <0.05. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to assess the significant variables from the multivariate analysis. We also estimated the overall survival rate using Kaplan-Meier analysis and compared the survival rates between the groups using log-rank analysis.

AEs occurred in 30 (18.6%) of the 161 patients in this study. Among them, the hospital mortality rate was 4.3% (7/161), the rate of >60-day postoperative hospitalization was 10.5% (17/161), and the rate of discharge with a modified Rankin scale score >4 was 9.3% (15/161). Postoperative major complications included reoperation (9.3%), stroke (1.8%), renal failure (5.6%), mediastinitis (0.0%), and prolonged ventilation (8.7%) (Table 2). Univariate analysis revealed the following risk factors for AEs: renal failure (creatinine clearance rate <30 mL; P=0.0055), NYHA class >3 (P=0.0018), congestive heart failure (P=0.0171), urgent or emergency operation (P=0.0003), cardiogenic shock (P=0.0361), poor cardiac function (ejection fraction <30%; P=0.0158), operation time >6 h (P=0.0168), perfusion time >3 h (P=0.0072), combined CABG (P=0.0196), and EuroSCORE II >10 (P<0.0001) (Table 3). Logistic regression analysis revealed the following significant risk factors for AEs: perfusion time >3 h (P=0.0331; OR, 2.685) and EuroSCORE II >10% (P<0.0001; OR, 8.232). The relationship between the EuroSCORE II and hospital death is shown in Figure 1A. The incidence of AEs increased significantly in proportion to the EuroSCORE. AEs occurred in >60% of patients with EuroSCORE II >10. We also investigated the relationship between age category and hospital death and the incidence of AEs (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the mortality rate increased slightly with age whereas AEs increased significantly in patients aged >80 years compared with those aged 70 s years.

| Adverse event | |

| Hospital death | 7/161 (4.3%) |

| Postop. hospital stay >60 days | 17/161 (10.5%) |

| Discharge status >Rankin 4 | 15/161 (9.3%) |

| Including any of above | 30/161 (18.6%) |

| Major complication | |

| Reoperation | 15/161 (9.3%) |

| Stroke | 3/161 (1.8%) |

| Renal failure | 9/161 (5.6%) |

| Mediastinitis | 0/161 (0%) |

| Prolonged ventilation | 14/161 (8.7%) |

SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement.

| Risk factor for adverse event | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| Age >85 years | 0.3109 | No. of diseased coronary vessels >2 |

0.2358 | |||

| BMI >26 | 0.2893 | MR >3 | 0.4899 | |||

| Current smoker | 0.6678 | TR >3 | 0.3324 | |||

| DM | 0.5156 | NYHA >3 | 0.0018 | |||

| DM on insulin | 0.8996 | HF | 0.0171 | |||

| HL | 0.1656 | Urgency | 0.0003 | |||

| CLCr <30 | 0.0055 | Arrhythmia | 0.3598 | |||

| HD | 0.1598 | AMI | 0.4959 | |||

| IE | 0.5092 | AP | 0.4636 | |||

| Active IE | 0.5092 | AP type | 0.2126 | |||

| Extracardiacarterypathy | 0.4014 | Cardiogenic shock | 0.0361 | |||

| ASO | 0.3176 | LV function bad | 0.0158 | |||

| History of CVD | 0.4899 | CCS >3 | 0.1177 | |||

| COPD >moderate | 0.9088 | Op. time >6 h | 0.0168 | |||

| Carotid stenosis | 0.2516 | Perfusion >3 h | 0.0072 | 0.0331 2.685: 1.083–6.661 |

||

| History of CVS op. | 0.4899 | CABG | 0.0196 | |||

| History of valve op. | 0.346 | Euro II >10 | <0.0001 | 0.0079 8.232: 2.153–31.476 |

||

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Relationship between (A) adverse event rate and EuroSCORE II and between (B) age category and adverse events after surgical aortic valve replacement.

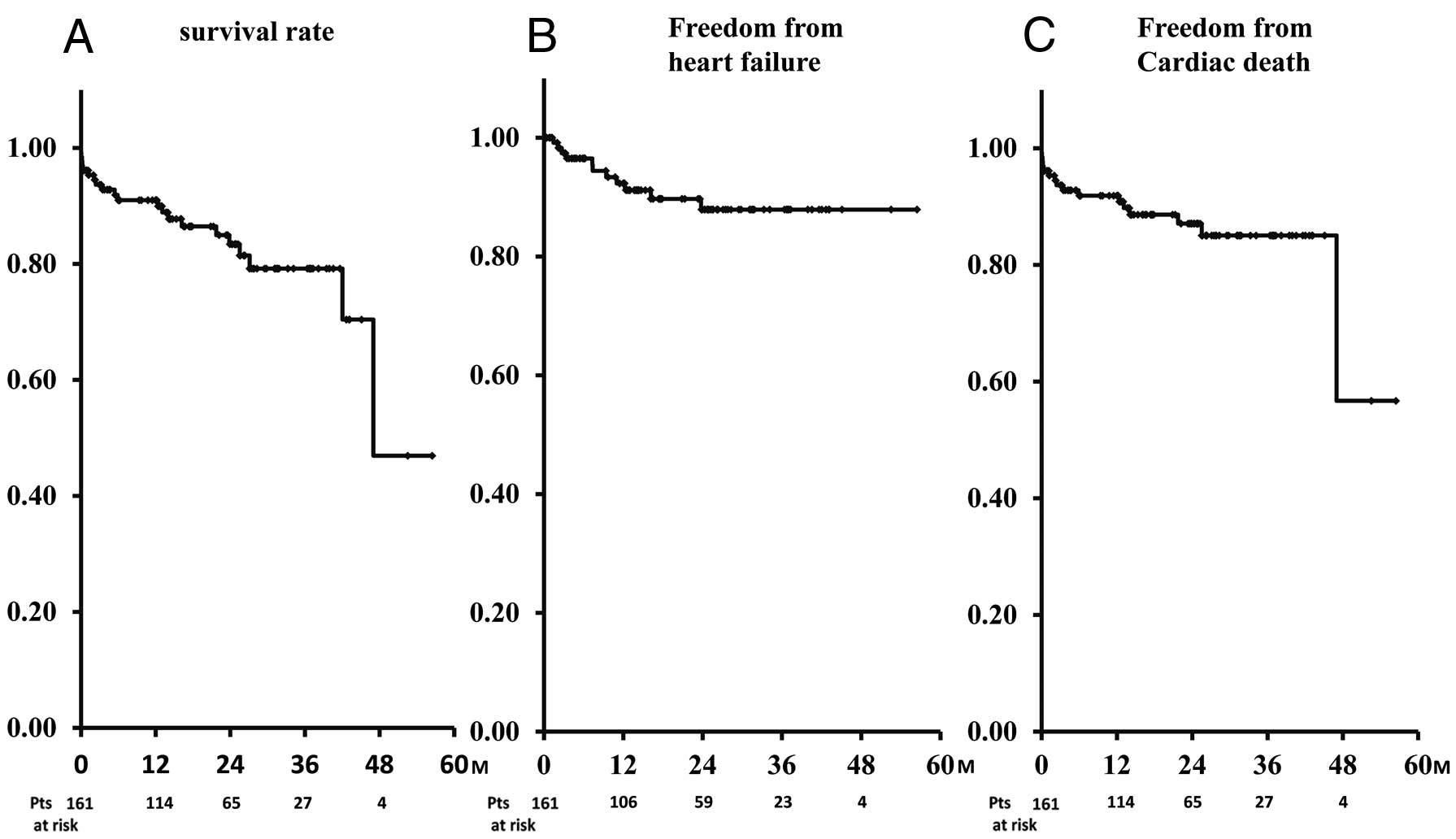

The overall follow-up data are shown in Figure 2. The overall survival rate at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years postoperatively was 91.0%, 83.3%, 79.3%, and 46.9%, respectively (Figure 2A). The rate of freedom from heart failure requiring hospitalization at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years postoperatively was 92.3%, 87.8%, 87.8%, and 87.8%, respectively (Figure 2B). The rate of freedom from cardiac death at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years postoperatively was 91.9%, 87.0%, 85.0%, and 56.7%, respectively (Figure 2C). These follow-up data are stratified according to the EuroSCORE II in Figure 3. Patients with a higher EuroSCORE II had a significantly worse prognosis with respect to overall survival, heart failure, and cardiac death.

Mid-term overall follow-up data after SAVR in octagenerians. (A) Survival rate. (B) Rate of freedom from cardiac failure. (C) Rate of freedom from cardiac death. SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement.

Mid-term follow-up data stratified according to Euroscore II. (A) Survival rate. (B) Rate of freedom from cardiac failure. (C) Rate of freedom from cardiac death.

The average medical cost during hospitalization for an operation was approximately 1.5-fold higher in patients with than in those without AEs (¥8,360,880 vs. ¥5,234,660; P=0.0016).

In the present study, we investigated AEs, including the functional status at discharge and during the postoperative hospitalization period in addition to hospital deaths and later clinical outcomes stratified according to the EuroSCORE II, in patients aged >80 years undergoing SAVR. Their hospital mortality rate was 4.3% and a total of 18.6% of patients developed AEs, which was almost 4-fold higher than the hospital mortality. Logistic regression analysis revealed that a perfusion time >3 h and a EuroSCORE II >10% (P<0.0001; OR, 8.232) were significant risk factors for AEs. Patients with a higher EuroSCORE II had a significantly worse prognosis in the later period. AEs also affected the medical cost during hospitalization.

In addition to hospital deaths and major complications, postoperative QOL and ADL are important for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Previously reported definitions of QOL vary. We consulted the SF36,11,12 the Seattle Angina Questionnaire,13 and an original questionnaire,14 but our definition of QOL was somewhat different to these. The patient’s general condition long after the operation is certainly important, but especially for elderly patients, the general status at discharge is a most important concern. A long hospitalization period is considered to weaken the general status of older patients,1 and moreover, an inability to ambulate at discharge negatively affects the QOL of both patients and their family. Therefore, we focused on the patients’ general condition both at discharge and during hospitalization. The clinical results of SAVR with respect to hospital deaths and major complications are reportedly satisfactory in octogenarians with relatively low surgical risk, but the incidence of both a long hospitalization period (>60 days) and depressed functional status (unable to walk without assistance and unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance) was relatively high in the present study. This discrepancy between death and these AEs is more prominent in patients aged >80 years (Figure 1B). Functional decline after surgery is a common and serious problem in elderly patients, resulting in changes in QOL and ADL. Approximately 30–60% of elderly patients develop new dependencies in ADL during their hospital stay.15 A decline in cognitive function after hospitalization is also a serious problem in elderly patients and tends to be substantial, even after controlling for illness.16 Efforts to decrease the incidence of these AEs are important.

The EuroSCORE II was found to be a strong predictor of AEs: >60% among patients with a EuroSCORE II >10%. An investigation of the effect of TAVR on these AEs in patients with a high risk score would help to identify suitable candidates. A shorter period of cardiopulmonary bypass might improve clinical outcomes. A relatively long cardiopulmonary bypass duration (>3 h) in patients who underwent SAVR occurred mostly in patients with multiple diseased coronary arteries. Hybrid percutaneous coronary intervention might be a feasible treatment choice in patients requiring multiple coronary artery revascularizations.

The clinical outcome in the later period after SAVR in the present octogenarians was satisfactory, as previously reported.6 However, in the mortality subgroup analysis in which recurrent heart failure and cardiac death were assessed according to stratification of the EuroSCORE II, the benefit decreased as the EuroSCORE II increased. In the PARTNER trial,9 an analysis of the stratified risk score (STS score) was performed in patients with AS who underwent medical treatment vs. TAVR. The mortality benefit with TAVR decreased as the STS score increased. In contrast, patients in the standard therapy group had a consistently poor prognosis irrespective of their STS risk stratum. However, patients with low STS risk score (<5%) who were not considered to be suitable candidates for SAVR, largely because of anatomical factors, had the most pronounced mortality reduction with TAVR. Few previous reports have documented the mid-term clinical outcomes of SAVR stratified according to the EuroSCORE II. This score might be feasible for predicting not only early outcomes, including AEs, as in the present study, but also later clinical outcomes.

Medical expense for elderly patients is now one of the largest concerns in aging societies because it is a burden on the national healthcare financial system. Hospital costs are reportedly 20% higher in older patients.17 The balance between medical costs and clinical outcomes is also important. Sollano et al reported that CABG in octogenarians is highly cost-effective.18 The present study revealed that AEs after valve surgery in octogenarians resulted in approximately 1.5-fold higher medical expenses. Preventing AEs might partially contribute to decreasing these costs.

Clinical results focusing on patient’s status at both discharge and during postoperative hospitalization of SAVR in patients aged >80 years was relatively high compared with hospital deaths, especially in patients with a longer perfusion time and high EuroSCORE. Further studies are necessary to define the indications for SAVR in patients aged >80 years in the era of TAVR.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.