Article ID: CJ-21-0556

Article ID: CJ-21-0556

Background: The PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk scores were developed to identify patients at risks of thrombotic and bleeding events individually after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, these scores have not been well validated in different cohorts.

Methods and Results: This 2-center registry enrolled 905 patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) undergoing primary PCI. Patients were divided into 3 groups according to the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores. The study endpoints included ischemic (cardiovascular death, recurrent MI, and ischemic stroke) and major bleeding events. Of 905 patients, 230 (25%) and 219 (24%) had high thrombotic and bleeding risks, respectively, with the PARIS scores, compared with 78 (9%) and 50 (6%) patients, respectively, with the CREDO-Kyoto scores. According to the 2 scores, >50% of patients with high bleeding risk had concomitant high thrombotic risk. During the mean follow-up period of 714 days, 163 (18.0%) and 95 (10.5%) patients experienced ischemic and bleeding events, respectively. Both PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto scores were significantly associated with ischemic and bleeding events after primary PCI. For ischemic events, the CREDO-Kyoto rather than PARIS thrombotic risk score had better diagnostic ability.

Conclusions: In the present Japanese cohort of acute MI patients undergoing contemporary primary PCI, the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores were discriminative for predicting ischemic and bleeding events.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for patients experiencing acute myocardial infraction (MI) reduces subsequent cardiac events and improves clinical outcomes, and has become a standard-of-care procedure.1 In patients undergoing PCI, previous studies have shown that both ischemic and bleeding events have a significant and similar magnitude effect on mortality.2–4 Recent guidelines recommend risk assessment for both ischemic and bleeding events, and several risk predicting models have been proposed.5,6 Although the DAPT (Dual Antiplatelet Therapy) and PRECISE-DAPT (Predicting Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing Stent Implantation and Subsequent Dual Antiplatelet Therapy) scores are guideline-recommended risk scoring systems, they were developed to guide DAPT duration after PCI and thus do not have capability to evaluate ischemic and bleeding risks individually.7,8 In this context, the PARIS (Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimen in Stented Patients) and CREDO-Kyoto (Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome Study in Kyoto) scores were developed from Western and Japanese PCI populations, respectively, with both including thrombotic and bleeding risk scores.9,10 However, these scores have not been well validated in a different cohort, specifically in patients with acute MI. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the predictive ability of PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores in patients with acute MI undergoing contemporary primary PCI.

Editorial p ????

This was a retrospective 2-center observational study. Between January 2012 and December 2018, 942 patients with acute MI underwent primary PCI at Chiba University Hospital or Eastern Chiba Medical Center. Acute MI was defined based on the fourth universal definition of MI.11 Patients with ST-elevation MI and non-ST-elevation MI were included in the study. Primary PCI was performed in all patients included in this study according to local standard practice. Patients received DAPT before or at the time of PCI, and the use of intracoronary imaging and contemporary drug-eluting stents were mostly preferred.12–15 The major exclusion criteria were duplicated patients (n=31), failed PCI (n=4), and no stent implantation (n=2). Thus, 905 patients with acute MI undergoing primary PCI with coronary stenting were finally included in the study.

All participants provided written informed consent for the PCI procedure; informed consent for the present study was obtained in the form of opt-out. This study was approved by the ethics committees of Chiba University Hospital and Eastern Chiba Medical Center, and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto Risk ScoresThrombotic and bleeding risks were assessed by the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk scores, as reported previously (Table 1).9,10 Briefly, the PARIS thrombotic and bleeding risk scores include 6 components in each. Diabetes, acute coronary syndrome presentation, current smoking, renal impairment, prior PCI, and a history of coronary artery bypass grafting are listed as thrombotic risk factors, whereas the bleeding risk score consists of age, body mass index, current smoking, anemia, renal impairment, and triple therapy (DAPT plus oral anticoagulation) on discharge.9 Conversely, the CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores include 8 and 7 items, respectively. Renal impairment, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, anemia, age, heart failure, diabetes, and chronic total occlusion are the components of the thrombotic risk score, whereas the bleeding risk score is comprised of a low platelet count, renal impairment, peripheral artery disease, heart failure, prior MI, malignancy, and atrial fibrillation.10 Patients were divided into low, intermediate, and high thrombotic and bleeding risks according to the thresholds (Table 1).9,10

| PARIS risk score | CREDO-Kyoto risk score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombotic | Bleeding | Thrombotic | Bleeding | |

| No. items | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 |

| Components and assigned scores |

DM (1 or 3); ACS (1 or 2); current smoking (1); CCr <60 mL/min (2); prior PCI (2); prior CABG (2) |

Age (1, 2, 3, or 4); BMI <25 or ≥35 kg/m2 (2); current smoking (2); anemia (3); CCr <60 mL/min (2); TT on discharge (2) |

CKD (2); AF (2); PAD (2); anemia (2); age (1); HF (1); DM (1); CTO (1) |

Low platelet (2); CKD (2); PAD (2); HF (2); prior MI (1); malignancy (1); AF (1) |

| Cut-off values | Low, 0–2; intermediate, 3–4; high, 5–10 |

Low, 0–3; intermediate, 4–7; high, 8–14 |

Low, 0–1; intermediate, 2–3; high, 4–12 |

Low, 0; intermediate, 1–2; high, 3–11 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCr, creatinine clearance; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CTO, chronic total occlusion; DM, diabetes; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TT, triple therapy.

Follow-up data were obtained from medical records at Chiba University Hospital and Eastern Chiba Medical Center. Guideline-recommended DAPT was administered for 12 months in patients with acute MI, although medical treatment was left to the discretion of treating physicians.

The primary endpoint of this study included both ischemic (cardiovascular death, recurrent MI, and ischemic stroke) and bleeding (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium Type 3 or 5) events. These events were adjudicated based on the consensus documents.11,16,17

Statistical AnalysisStatistical analysis was performed with JMP Pro 15.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data are expressed as the mean±SD or as frequencies (%). Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to calculate the time to clinical endpoints, and the log-rank test was used to evaluate the significance of between-group differences. Ischemic and bleeding event rates were also evaluated with landmark analysis using the date of discharge as the landmark, excluding patients who died during the index hospitalization. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted on ischemic and bleeding events. The area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curve was compared using the Delong method. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

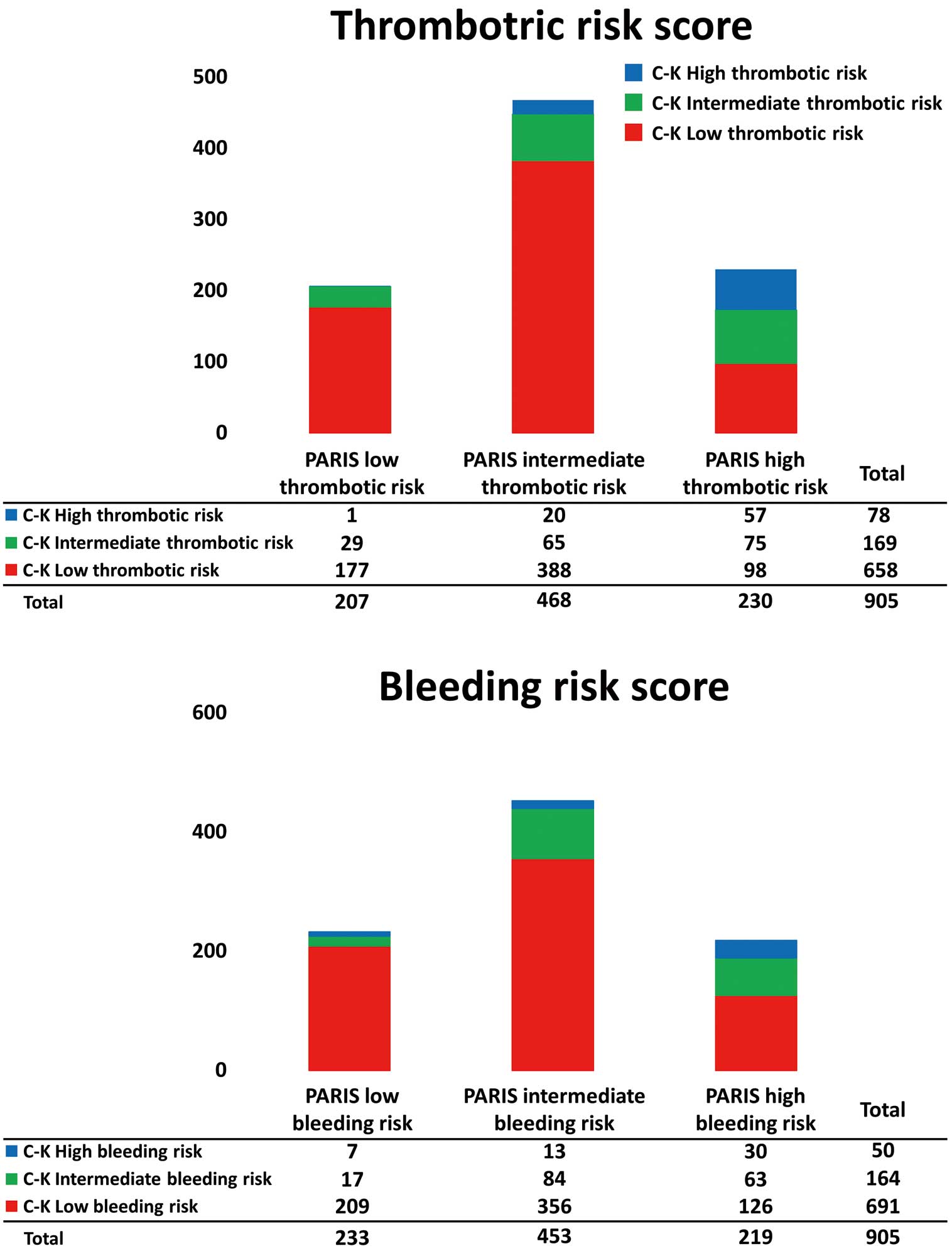

Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1 list baseline patient and procedural characteristics. Using the PARIS thrombotic and bleeding risk scores, patients were divided into low, intermediate, and high thrombotic risk (207 [23%], 468 [52%], and 230 [25%], respectively) and low, intermediate, and high bleeding risk (233 [26%], 453 [50%], and 219 [24%], respectively) groups. Similarly, using the CREDO-Kyoto score, patients were divided into low, intermediate, and high thrombotic risk (658 [73%], 169 [19%], and 78 [9%], respectively) and low, intermediate, and high bleeding risk (691 [76%], 164 [18%], and 50 [6%], respectively) groups (Figure 1).

| Age (years) | 66.8±12.1 |

| Male sex | 700 (77) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1±3.6 |

| Hypertension | 607 (67) |

| DM | 340 (38) |

| Dyslipidemia | 550 (61) |

| Current smoker | 311 (34) |

| Prior MI | 54 (6) |

| Prior PCI | 76 (8) |

| Prior CABG | 16 (2) |

| Prior HF | 17 (2) |

| AF | 56 (6) |

| PAD | 18 (2) |

| Malignancy | 53 (6) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 64.3±23.8 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.8±2.2 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 22.8±7.7 |

| Type of MI | |

| STEMI | 616 (68) |

| NSTEMI | 289 (32) |

| Killip class on admission | |

| I | 600 (66) |

| II | 74 (8) |

| III | 57 (6) |

| IV | 174 (19) |

| Cardiac arrest on admission | 122 (13) |

| Medications at discharge | |

| Antithrombotic treatment | |

| DAPT | 828 (91) |

| TT | 58 (6) |

| Aspirin | 859 (95) |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 855 (94) |

| Clopidogrel | 441 (52) |

| Prasugrel | 412 (48) |

| Ticlopidine | 2 (0.2) |

| Oral anticoagulant | 99 (11) |

| β-blocker | 648 (72) |

| ACEI or ARB | 716 (79) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 188 (21) |

| Diuretic | 187 (21) |

| Statin | 772 (85) |

| Culprit vessel | |

| RCA | 269 (30) |

| LMT/LAD | 460 (51) |

| LCX | 145 (16) |

| Undetermined | 31 (3) |

| CTO | 24 (3) |

| Access site | |

| Radial artery | 775 (86) |

| Femoral artery | 110 (12) |

| Brachial artery | 20 (2) |

| Mechanical circulatory support | |

| IABP | 106 (12) |

| ECMO | 55 (6) |

| IVUS | 876 (97) |

| Drug-eluting stent | 823 (91) |

Values are given as the mean±SD or as n (%). ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex; LMT, left main trunk; NSTEMI, non ST-elevation myocardial infarction; RCA, right coronary artery; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Distribution of the thrombotic risk score categories according to bleeding risk score categories as determined by the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk scores.

More than half the patients with a high bleeding risk had a concomitant high thrombotic risk as evaluated with both the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk scores (Figure 1). The PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto scores were often discordant. For example, among patients with a high PARIS bleeding risk, 58% were classified as low bleeding risk by the CREDO-Kyoto score (Figure 2).

Distribution of the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto (C-K) risk score categories for thrombotic and bleeding risks.

During the mean follow-up period of 714±710 days, 163 (18.0%) and 95 (10.5%) patients had ischemic and bleeding events, respectively (Table 3). Gastrointestinal (35%), vascular (access site; 26%), and cerebral (11%) bleeding were frequent types of major bleeding events. Both PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores were significantly associated with ischemic and bleeding events (Supplementary Table 2; Figures 3,4). There were no significant differences in ischemic and bleeding events between PARIS low and intermediate risk groups (Figures 3,4). Landmark analysis after discharge showed similar results, but the PARIS thrombotic risk score was not significantly associated with ischemic events after discharge (Supplementary Figure). In ROC curve analysis, the PARIS (AUC 0.56, P=0.002) and CREDO-Kyoto (AUC 0.65, P<0.001) thrombotic risk scores predicted ischemic events. The CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic risk score had a better diagnostic ability than the PARIS thrombotic risk score (P<0.001; Figure 5). Both the PARIS (AUC 0.62, P<0.001) and CREDO-Kyoto (AUC 0.63, P<0.001) bleeding risk scores were predictive for bleeding events, with no between-group difference (P=0.69; Figure 5).

| Variable | No. patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Ischemic events | 163 (18.0) |

| Cardiovascular death | 105 (11.6) |

| Recurrent MI | 40 (4.4) |

| Ischemic stroke | 36 (4.0) |

| Bleeding events | 95 (10.5) |

| BARC 3 | 87 (9.6) |

| BARC 5 | 8 (0.9) |

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MI, myocardial infarction.

Cumulative incidence of ischemic events according to PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk score categories. Ischemic events were defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, recurrent myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke.

Cumulative incidence of major bleeding events according to the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk score categories. Major bleeding events were defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium Type 3 or 5 events.

Receiver operating characteristics curve analysis for ischemic and bleeding events with area under the curve (AUC) comparisons of the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto (C-K) risk scores.

This study demonstrated that, in patients with acute MI undergoing contemporary primary PCI, the PARIS risk score determined approximately one-quarter of patients as having high thrombotic and bleeding risks, whereas the CREDO-Kyoto score only classified <10% of patients as being in the high thrombotic and bleeding risk groups. According to the 2 scores, more than half the patients with a high bleeding risk had a concomitant high thrombotic risk in the present Japanese cohort. With different components, the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto scores were often discordant. Although both PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk scores were predictive for ischemic and bleeding events, the CREDO-Kyoto scores were more discriminative, especially for ischemic events.

Ischemic and Bleeding RisksClinical outcomes in patients with acute MI have improved considerably in recent decades, but MI remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide.18,19 Recent nationwide registry data clearly show that over the past 20 years, the introduction of invasive and more intense antithrombotic treatment has been associated with substantial reductions in ischemic events and mortality, but an increase in bleeding events following MI.20 It is well known that both ischemic and bleeding events after MI are strongly linked with subsequent mortality.2–4 For example, in a large-scale retrospective cohort (n=32,906), major bleeding events were associated with an increased risk of death in patients undergoing PCI (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.30–2.00), similar to that after MI (adjusted HR 1.91; 95% CI 1.62–2.25).4 Therefore, recent guidelines recommend risk assessment from the viewpoint of both ischemic and bleeding events,5,6 which may be useful for guiding patient care and antithrombotic therapy.

PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto Risk ScoresCurrent international guidelines recommend using the DAPT and PRECISE-DAPT risk scoring systems.5,6 However, these scores were exclusively developed to guide the duration of DAPT after PCI, and so are not able to assess ischemic and bleeding risk individually.7,8 The PARIS risk scores were developed from a prospective multicenter observational study of patients undergoing PCI in the US and European countries, with only 8% of patients having acute MI. From the derivation cohort, 6 items were identified as factors associated with thrombotic and bleeding events (Table 1). In the original paper reporting the PARIS risk score, patients at high bleeding risk accounted for <10% of a total cohort, in which nearly 40% of patients were classified as having concomitant high thrombotic risk.9 The CREDO-Kyoto risk scores were generated from a Japanese cohort of 4,778 participants treated by PCI with first-generation sirolimus-eluting stents, 15% of whom were acute MI patients, with 8 and 7 items identified as significant factors associated with thrombotic and bleeding events, respectively (Table 1). According to the CREDO-Kyoto score, 13% of patients in the original derivation cohort were at high bleeding risk, of whom 59% had a concomitant high thrombotic risk.10 Patients at high bleeding risk accounted for 24% and 6% of the present MI cohort as assessed by the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto scores, respectively, compared with 9% and 13% in the original reports, indicating that different risk scores in different populations determine patient risks differently. Nevertheless, the present study reinforces the fact that patients at high bleeding risk are likely to have concomitant high thrombotic risk. Both PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk scores were validated with another cohort in the original papers, although they have not been well investigated by different study groups.

In the present study, the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores were both predictive for subsequent ischemic and bleeding events after MI, suggesting the usefulness of these scores for risk stratification in patients with acute MI. Interestingly, the CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic score had a higher AUC than the PARIS thrombotic risk score for ischemic events, and the CREDO-Kyoto rather than PARIS risk score was more discriminative, especially in the low- and intermediate-risk groups. Given that CREDO-Kyoto scores were derived from a Japanese cohort and that the present study was conducted in a Japanese cohort, racial differences may play an important role in predicting ischemic and bleeding risks. Only a few similar components, such as diabetes and renal impairment, are included in the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto risk scores, and most items are discordant, illustrating the significant differences in the 2 risk scores from Western and Eastern countries. It should be also noted that the CREDO-Kyoto rather than PARIS risk score identified a lower number of patients at high thrombotic/bleeding risks. A subanalysis of the ReCre8 trial recently investigated the diagnostic ability of PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto scores and found high PARIS thrombotic and bleeding risks in 15% and 8% of patients, respectively, compared with high CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risks in 5% and 6% of patients, respectively.21 That subanalysis showed that the discriminative capability of the PARIS thrombotic and bleeding risk scores, evaluated as the AUC, was marginal (0.59 and 0.55, respectively), whereas the CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores exhibited moderate discrimination (0.68 and 0.67, respectively).21 Although the ReCre8 was a device-specific randomized trial and used a specific antithrombotic regimen in which troponin-negative patients received DAPT for only 1 month, the overall results may be in line with those of the present study. Further studies are warranted to confirm our results and to clarify whether risk score-based patient care can improve clinical outcomes in large-scale prospective cohorts.22–25

Study LimitationsSome limitations of this study should be considered. The present study was a retrospective study, and the sample size was modest. Medical treatment was left to the discretion of the treating physicians, and antithrombotic regimens (e.g., the duration of DAPT) may have affected the results. Because the PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto scores can determine thrombotic and bleeding risks individually, these 2 risk scores were evaluated in the present study. However, the impact of different risk predicting models (e.g., Academic Research Consortium definition of High Bleeding Risk) is unknown.26–29 In addition, although the results of the present study suggest the possible superiority of the CREDO-Kyoto score over the PARIS score, real-world data from Western countries are needed to validate the CREDO-Kyoto risk scores.

The PARIS and CREDO-Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores were demonstrated to be significantly predictive scoring systems in patients with acute MI undergoing primary PCI. In this contemporary dataset in Japan, more than 50% of patients at high bleeding risk had concomitant high thrombotic risk. The 2 different risk scores often determined patient risks differently. The CREDO-Kyoto rather than PARIS risk scores may be more discriminative in the present cohort, suggesting racial differences in scoring systems.

This study did not receive any specific funding.

Y.K. is a member of Circulation Journal’s Editorial Team. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This study was approved by the ethics committees at Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine (Approval no. 3933) and Eastern Chiba Medical Center (Approval no. 131).

The data will not be shared.

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-21-0556