Abstract

Background: Kampo, a Japanese herbal medicine, is approved for the treatment of various symptoms/conditions under national medical insurance coverage in Japan. However, the contemporary nationwide status of Kampo use among patients with acute cardiovascular diseases remains unknown.

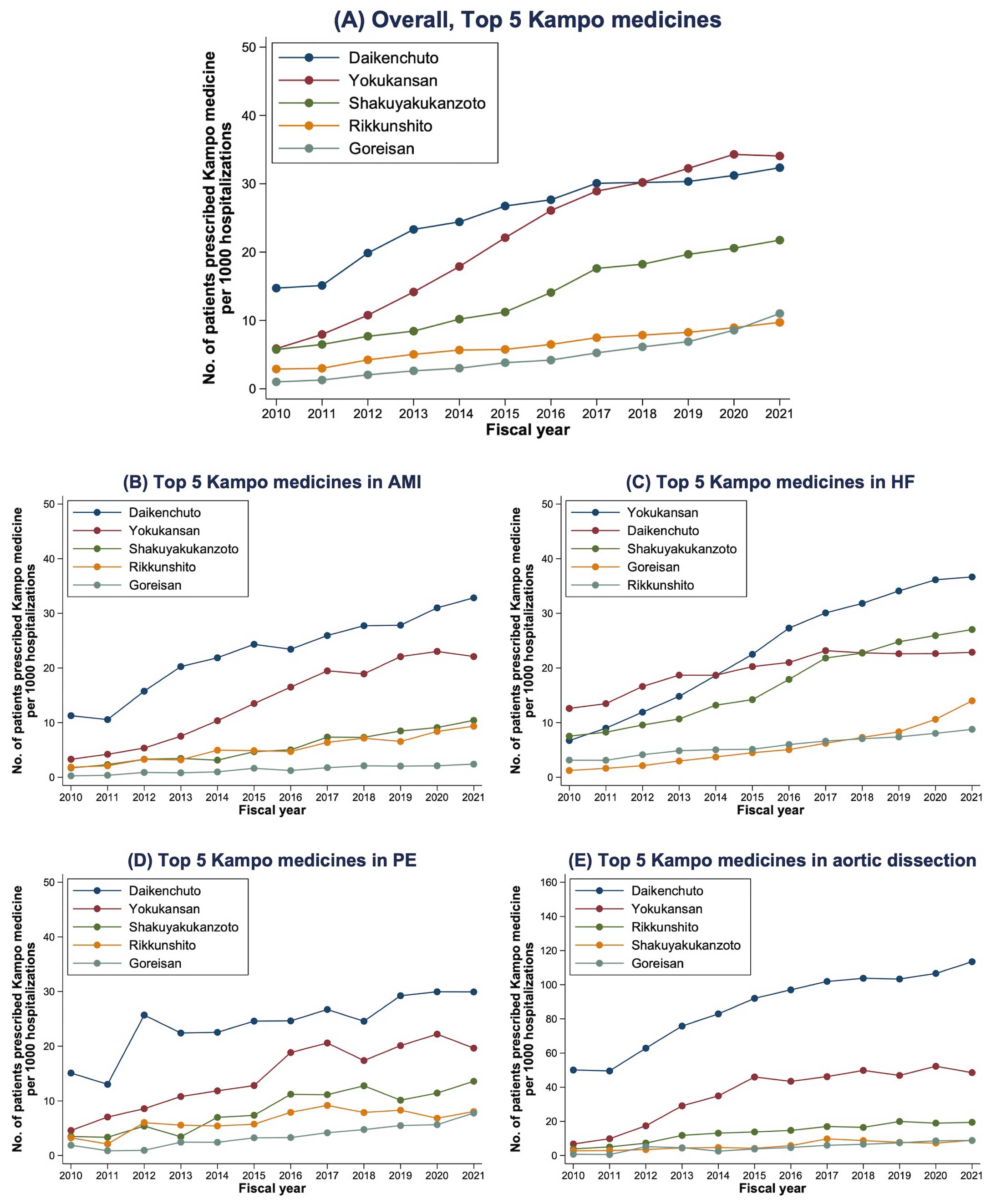

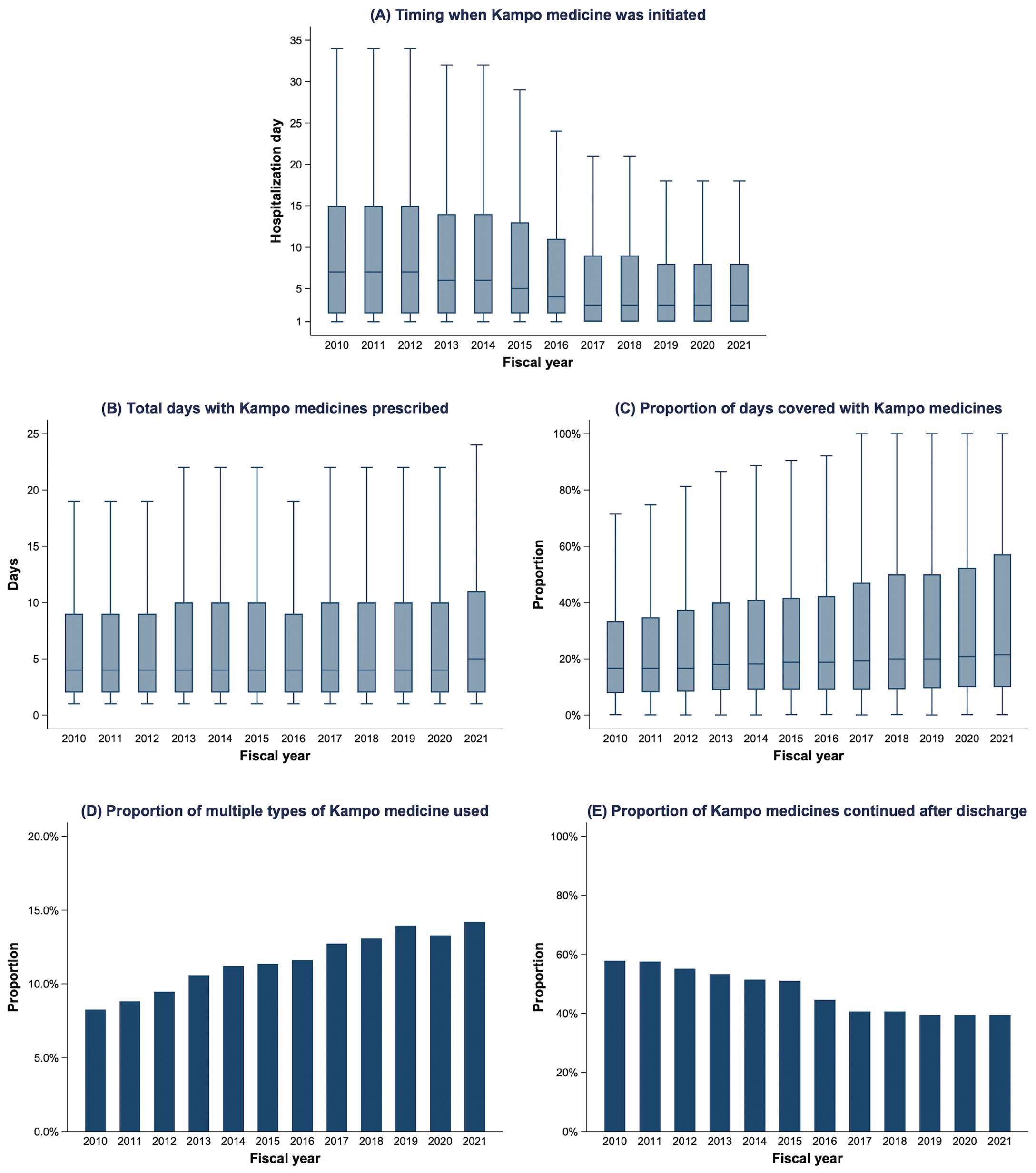

Methods and Results: Using the Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination database, we retrospectively identified 2,547,559 patients hospitalized for acute cardiovascular disease (acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, or aortic dissection) at 1,798 hospitals during the fiscal years 2010–2021. Kampo medicines were used in 227,008 (8.9%) patients, with a 3-fold increase from 2010 (4.3%) to 2021 (12.4%), regardless of age, sex, disease severity, and primary diagnosis. The top 5 medicines used were Daikenchuto (29.4%), Yokukansan (26.1%), Shakuyakukanzoto (15.8%), Rikkunshito (7.3%), and Goreisan (5.5%). From 2010 to 2021, Kampo medicines were initiated earlier during hospitalization (from a median of Day 7 to Day 3), and were used on a greater proportion of hospital days (median 16.7% vs. 21.4%). However, the percentage of patients continuing Kampo medicines after discharge declined from 57.9% in 2010 to 39.4% in 2021, indicating their temporary use. The frequency of Kampo use varied across hospitals, with the median percentage of patients prescribed Kampo medications increasing from 7.7% in 2010 to 11.5% in 2021.

Conclusions: This nationwide study demonstrates increasing Kampo use in the management of acute cardiovascular diseases, warranting further pharmacoepidemiological studies on its effectiveness.

The socioeconomic burden of cardiovascular diseases has been increasing worldwide.1 In Japan, cardiovascular diseases are the second leading cause of death after cancer, accounting for approximately 15% of deaths.2 Moreover, cardiovascular/cerebrovascular diseases have been associated with the highest medical expenses in Japan (JPY6.1 trillion=approximately USD44 billion; 19% of total medical costs in 2021).3 To improve these circumstances, the Cerebrovascular and Cardiovascular Disease Control Act of the Japanese national law was enacted in December 2018, and the Japanese National Plan for Promotion of Measures Against Cerebrovascular and Cardiovascular Disease was published in October 2020.4 These recent policies reflect the need for improvement in the management of cardiovascular disease.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is defined as a broad set of healthcare practices that are not part of conventional medicine, with the use of CAM increasing worldwide in recent decades.5 CAM is used for patients with cardiovascular diseases despite limited evidence regarding its efficacy.6,7 Studies on the prevalence of CAM use are warranted to assess the implications of CAM for contemporary healthcare systems and to determine the need for research and education on CAM.8 Kampo medicine, a traditional Japanese herbal medicine formulated using natural agents based on traditional Chinese medicine, is a type of CAM.9 Kampo medicine is used to treat various symptoms (e.g., fatigue, frailty, muscle cramps, general malaise, decreased appetite, constipation, and leg edema) as an alternative or adjunct to Western medicine.10 Kampo medicine prescriptions have been approved under the coverage of the Japanese national health insurance since 1976.10,11 In 2021, the annual production value of Kampo medicines was JPY190 billion (approximately USD1.4 billion), accounting for approximately 2% of the total production value in Japan.12

Given the high socioeconomic burden of cardiovascular disease and the common use of Kampo medicine as CAM under the Japanese healthcare system, it is important for healthcare providers to understand the nationwide trends and practice patterns in the Kampo medication among patients with cardiovascular disease, in the context of medical resource utilization. However, to date, such data have been unavailable. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to describe the contemporary status of Kampo medication use in patients hospitalized for major cardiovascular disease in Japan using a large national inpatient database.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study used data from the Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) database. This database has been described previously.13 Briefly, the DPC database is a nationwide inpatient database in which >7 million hospitalizations are registered annually from >1,000 acute care hospitals located throughout Japan, representing approximately 50% of all hospitalizations in Japan. Although all university hospitals are obliged to participate in the database, all other hospitals participate voluntarily.

The Institutional Review Board of The University of Tokyo approved the present study and waived the requirement for informed consent from individual patients because all patient data were anonymized and deidentified (Approval no. 3501-(5)). The data used in this study are not publicly available owing to contracts with hospitals that provide data to the database.

The following clinical data are included in the DPC database in a uniform format: patient demographics, type and date of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, surgeries, medications, and discharge status (dead or alive). Diagnoses are recorded in the form of International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes with Japanese text, whereas examinations and procedures are recorded using unique Japanese administrative codes. The diagnoses and procedures recorded in the DPC database have been previously validated with high accuracy.14–16 Attending physicians are obliged to record one ICD-10 diagnosis as the primary diagnosis for admission per hospitalization in the DPC database.

Study Cohort and Patient Characteristics

We identified hospitalizations of patients aged ≥20 years who were admitted with one of the following as the primary diagnosis for admission between July 1, 2010, and March 31, 2022: acute myocardial infarction (AMI; ICD-10 I21.x), heart failure (HF; ICD-10 I50.x), pulmonary embolism (PE; ICD-10 I26.x), and aortic dissection (ICD-10 I71.0). No exclusion criteria were applied. The fiscal year in Japan includes the 12 months from April 1 in one calendar year to March 31 in the following year. Thus, the present study covered the 12-fiscal year period of 2010–2021; data for the 2010 fiscal year included 9-month data from July 1, 2010, to March 31, 2011, because data have been collected consecutively in the database since July 2010. In the present study, all the study years are presented as fiscal years.

The following baseline characteristics were included: age, sex, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, renal disease, liver disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and malignancy; Supplementary Table), the severity of disease, fiscal year, in-hospital death, and length of hospital stay. “Severe” cases were defined as patients who received catecholamines (dopamine, dobutamine, norepinephrine, or epinephrine), mechanical circulatory support (intra-aortic balloon pumping, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or catheter-based ventricular assist device), mechanical ventilation, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation on the day of admission, which were assumed as surrogates of shock/circulatory failure, respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest at admission, respectively.

Kampo Medicine

The use of Kampo medicines was identified from data on the medications prescribed during hospitalization. Kampo use was defined as the use of any of the 149 Kampo medicines available in Japan during the study period. In patients who received at least 1 Kampo medication during hospitalization, we extracted data on the timing of initiation of Kampo medication during hospitalization (i.e., the hospital day when Kampo medicine was initiated, where the day of admission is Day 1), the total number of days of Kampo use, the proportion of hospital days on which Kampo was used (calculated by dividing the total number of days of Kampo use by the length of the hospital stay), and the proportion of patients continuing Kampo medicines after discharge. In addition, all Kampo medicines were ranked by the frequency of in-hospital use during the entire study period, with the top 5 Kampo medicines for the overall study population identified, as well as the top 5 for each of the primary diagnoses (AMI, HF, PE, or aortic dissection).

Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as the mean±SD or as median with interquartile range (IQR). Trend analyses for categorical and continuous variables were performed using the Cochran–Armitage and Jonckheere–Terpstra tests, respectively. We compared patient characteristics and in-hospital outcomes between patients treated with and without Kampo medicines using the absolute standardized difference, where >0.10 indicates a significant difference. We obtained predictive margins from the modified Poisson regression to estimate the crude and adjusted number of patients prescribed Kampo medicines and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) over 12 fiscal years after multivariable adjustment for age, sex, severity of disease, and primary diagnosis.17 We also examined the marginal effects in the interaction of fiscal years with the following clinically relevant subgroups: age (<50, 50–74, or ≥75 years), sex (male or female), disease severity (severe or non-severe), and primary diagnosis (AMI, HF, PE, or aortic dissection). We set a 2-sided significance level of 0.05 and conducted all statistical analyses using Stata version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study Population

We identified 2,547,559 hospitalizations with acute cardiovascular disease as the primary diagnosis registered from 1,798 hospitals in the DPC database between July 2010 and March 2022 (fiscal years 2010–2021): 532,656 (20.9%) with AMI, 1,742,518 (68.4%) with HF, 80,044 (3.1%) with PE, and 192,341 (7.6%) with aortic dissection. Patient characteristics and in-hospital outcomes for the overall study population and subgroup cohorts stratified by primary diagnosis are presented in Table 1. Overall, the mean age was 76.7±13.3 years and patients aged ≥75 years accounted for nearly two-thirds of the cohort; 56.1% of patients were men. Half the patients had hypertension, whereas one-quarter had diabetes. Severe cases were observed in 23.6% of patients, with the proportion ranging from 10.1% for PE to 41.0% for AMI. The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 11.9%, ranging from 8.6% for PE to 17.8% for aortic dissection.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and In-Hospital Outcomes for the Overall Population and According to Primary Diagnosis

| |

Overall

(n=2,547,559) |

AMI

(n=532,656) |

HF

(n=1,742,518) |

PE

(n=80,044) |

Aortic dissection

(n=192,341) |

| Age, years |

76.7±13.3 |

70.3±13.2 |

79.7±12.1 |

69.0±15.6 |

70.7±13.4 |

| Age group |

| 20–49 years |

116,925 (4.6) |

41,342 (7.8) |

48,694 (2.8) |

11,134 (13.9) |

15,755 (8.2) |

| 50–74 years |

816,655 (32.1) |

272,374 (51.1) |

417,395 (24.0) |

34,381 (43.0) |

92,505 (48.1) |

| ≥75 years |

1,613,979 (63.4) |

218,940 (41.1) |

1,276,429 (73.3) |

34,529 (43.1) |

84,081 (43.7) |

| Male sex |

1,430,437 (56.1) |

387,217 (72.7) |

899,529 (51.6) |

33,011 (41.2) |

110,680 (57.5) |

| Hypertension |

1,348,685 (52.9) |

318,432 (59.8) |

885,714 (50.8) |

24,018 (30.0) |

120,521 (62.7) |

| Diabetes |

648,089 (25.4) |

153,711 (28.9) |

465,666 (26.7) |

10,101 (12.6) |

18,611 (9.7) |

| Dyslipidemia |

685,063 (26.9) |

304,363 (57.1) |

332,884 (19.1) |

12,583 (15.7) |

35,233 (18.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation |

566,259 (22.2) |

31,601 (5.9) |

516,986 (29.7) |

4,440 (5.5) |

13,232 (6.9) |

| Renal disease |

327,217 (12.8) |

30,268 (5.7) |

284,581 (16.3) |

2,050 (2.6) |

10,318 (5.4) |

| Liver disease |

51,167 (2.0) |

6,207 (1.2) |

39,419 (2.3) |

1,528 (1.9) |

4,013 (2.1) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

152,718 (6.0) |

13,672 (2.6) |

126,890 (7.3) |

4,419 (5.5) |

7,737 (4.0) |

| Malignancy |

119,574 (4.7) |

14,815 (2.8) |

88,534 (5.1) |

10,339 (12.9) |

5,886 (3.1) |

| Severity of disease |

| Non-severe |

1,947,452 (76.4) |

314,430 (59.0) |

1,426,940 (81.9) |

71,978 (89.9) |

134,104 (69.7) |

| Severe |

600,107 (23.6) |

218,226 (41.0) |

315,578 (18.1) |

8,066 (10.1) |

58,237 (30.3) |

| In-hospital death |

304,109 (11.9) |

70,409 (13.2) |

192,577 (11.1) |

6,889 (8.6) |

34,234 (17.8) |

| Length of stay (days) |

16.0 [10.0–27.0] |

13.0 [9.0–19.0] |

17.0 [11.0–29.0] |

15.0 [10.0–23.0] |

20.0 [9.0–30.0] |

Values are presented as the mean±SD, median [interquartile range], or n (%). AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HF, heart failure; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Trends in Kampo Use in the Overall Population and in Subgroups

Overall, Kampo medicines were used in 227,008 (8.9%) patients, with a significantly increasing trend over 12 years (P value for trend <0.001) and a nearly 3-fold increase from 4.3% in 2010 to 12.4% in 2021 (Figure 1A). This increasing trend remained consistent after multivariable adjustment (Figure 1B) and was observed regardless of age, sex, severity of disease, and primary diagnosis (Figure 1C–E; all P value for trend <0.001). Patients treated with Kampo medicines were older, more often female, more frequently had a primary diagnosis of HF or aortic dissection, and had a longer hospital stay than those not treated with Kampo medicine (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and In-Hospital Outcomes of Patients Treated With and Without Kampo Medicines

| |

Kampo use during hospitalization |

Absolute

standardized

differenceA |

Yes

(n=227,008) |

No

(n=2,320,551) |

| Age (years) |

79.1±11.9 |

76.5±13.4 |

0.21 |

| Age group |

|

|

0.21 |

| 20–49 years |

6,355 (2.8) |

110,570 (4.8) |

|

| 50–74 years |

56,992 (25.1) |

759,663 (32.7) |

|

| ≥75 years |

163,661 (72.1) |

1,450,318 (62.5) |

|

| Male sex |

120,923 (53.3) |

1,309,514 (56.4) |

0.06 |

| Hypertension |

115,290 (50.8) |

1,233,395 (53.2) |

0.05 |

| Diabetes |

57,411 (25.3) |

590,678 (25.5) |

0.00 |

| Dyslipidemia |

48,603 (21.4) |

636,460 (27.4) |

0.14 |

| Atrial fibrillation |

53,821 (23.7) |

512,438 (22.1) |

0.04 |

| Renal disease |

36,238 (16.0) |

290,979 (12.5) |

0.10 |

| Liver disease |

5,273 (2.3) |

45,894 (2.0) |

0.02 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

16,646 (7.3) |

136,072 (5.9) |

0.06 |

| Malignancy |

13,806 (6.1) |

105,768 (4.6) |

0.07 |

| Severity of disease |

|

|

0.02 |

| Non-severe |

171,742 (75.7) |

1,775,710 (76.5) |

|

| Severe |

55,266 (24.3) |

544,841 (23.5) |

|

| Primary diagnosis |

|

|

0.28 |

| AMI |

29,189 (12.9) |

503,467 (21.7) |

|

| HF |

163,143 (71.9) |

1,579,375 (68.1) |

|

| PE |

6,151 (2.7) |

73,893 (3.2) |

|

| Aortic dissection |

28,525 (12.6) |

163,816 (7.1) |

|

| In-hospital death |

22,975 (10.1) |

281,134 (12.1) |

0.06 |

| Length of stay (days) |

23.0 [14.0–40.0] |

16.0 [10.0–25.0] |

0.29 |

Values are presented as the mean±SD, median [interquartile range], or n (%). AAn absolute standardized difference >0.10 indicates a significant difference between the groups. Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Top 5 Kampo Medicines

Daikenchuto (29.4%) was the most frequently used Kampo medicine, followed by Yokukansan (26.1%), Shakuyakukanzoto (15.8%), Rikkunshito (7.3%), and Goreisan (5.5%; Figure 2A). These Kampo medicines were the top 5 medicines across the different primary diagnoses, although the ranking orders differed between the HF and other diagnosis subgroups (Figure 2B–E). In the HF subgroup, Daikenchuto was most frequently used before 2014, whereas Yokukansan has been the most frequent Kampo medicine used since 2015 and Shakuyakukanzoto has been the second most frequent Kampo medicine used since 2019 (Figure 2C). In the aortic dissection subgroup, Daikenchuto has been increasingly used in >10% of patients since 2017, reaching 18% by 2021 (Figure 2E).

Timing of Initiation, Days Covered, and Post-Discharge Continuation of Kampo Medicines

Among the 227,008 patients receiving Kampo medicines, the time to initiation during hospitalization decreased over the years. In 2010, Kampo medicines were initiated on a median of Day 7 (IQR Days 2–15), compared with Day 3 (IQR Days 1–8) in 2021 (Figure 3A). The total number of days on which Kampo medications were used remained stable (median 4 vs. 5 days in 2010 and 2021, respectively; Figure 3B). Meanwhile, the proportion of days during hospitalization on which Kampo medicines were used increased from a median of 16.7% (IQR 7.8–33.3%) in 2010 to 21.4% (IQR 10.0–57.1%) in 2021 (Figure 3C). The proportion of patients who received ≥2 types of Kampo medicine increased from 8.3% in 2010 to 14.2% in 2021 (Figure 3D). Despite the increasing use of Kampo medicines during hospitalization, the proportion of patients discharged alive who continued Kampo medicines after discharge decreased from 57.9% in 2010 to 39.4% in 2021 (Figure 3E).

Hospital Variation in Kampo Use

Overall, the median proportion of patients prescribed Kampo across hospitals in 2010 was 7.7% (IQR 4.2–12.5%), which increased to 11.5% (7.3–16.2%) in 2021 (Figure 4A). Hospital variations in Kampo prescriptions were observed across hospitals. For example, in 2021, the median proportion of patients prescribed Kampo across all hospitals in the database was 11.5% (IQR 7.3–16.2%), but this ranged from 0% to >50% at individual hospitals (Figure 4B).

Discussion

This nationwide study in Japan revealed several notable findings regarding the use of Kampo medicines in patients with acute cardiovascular disease. The frequency of Kampo medications increased by approximately 3-fold over the 12 years, regardless of patient background. The top 5 Kampo medicines were the same across the primary diagnoses, although the ranking orders of the 5 medicines differed between the HF and other subgroups. Over the period 2010–2021, Kampo medicines were initiated earlier during hospitalization and were used on a larger proportion of hospital days. However, there was a decrease in the continuation of Kampo medicines after discharge over the 12-year period, indicating their temporary use during hospitalization in the majority of cases. The frequency of Kampo prescriptions varied across hospitals, with the overall frequency increasing over the years.

Current Status of Kampo Use in Cardiovascular Medicine

Kampo medicines are considered potentially effective therapies for the treatment of several symptoms, such as frailty, sarcopenia, fatigue, anorexia, constipation, and volume overload.18 Such symptoms are prevalent in patients with cardiovascular disease,19 who often have advanced age and multiple comorbidities. To date, only one randomized trial has focused on the efficacy of Kampo medicine for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.20 That single-center open-label trial randomized 40 patients with acute decompensated HF to receive Mokuboito in addition to standard HF therapy (n=19) or standard HF therapy alone (n=21). The results demonstrated that Mokuboito significantly improved HF-related symptoms.20 Other studies focusing on the use of Kampo in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases are limited to a small observational study21 or case reports.22,23 There are no guidelines for Kampo use in patients with cardiovascular disease. However, our findings demonstrate a significant increasing trend in the use of Kampo medications in patients with cardiovascular disease over the 12-year study period. Notably, this trend was consistent even after multivariable adjustments for age, sex, severity, and primary diagnosis. This highlights that the observed increase does not simply reflect the influence of the aging society in Japan; rather, it represents an actual increase in the use of Kampo medications in real-world clinical practice.

One possible reason for this increase is the introduction of Kampo medicine in the medical education system in Japan. In 2001, Kampo medicine was introduced as a part of the Model Core Curriculum for Japanese medical students,24 and since 2005 all medical universities have been educating their medical students regarding Kampo medicine.25 Thus, the number of physicians receiving education regarding Kampo medicine has increased over the past decade, which may explain why the use of Kampo medication is more common in clinical practice.

Types of Kampo Medicine Used in Patients With Acute Cardiovascular Disease

In the present study, the top 5 Kampo medicines were Daikenchuto, Yokukansan, Shakuyakukanzoto, Rikkunshito, and Goreisan, which are different from the top 5 Kampo medicines prescribed on an outpatient basis in a previous study on a general population (Kakkonto, Shoseiryuto, Maoto, Bakumondoto, and Goreisan).26 One reason for this difference may be the advanced age of patients with acute cardiovascular disease. Daikenchuto is considered effective for improving gastrointestinal motility and constipation,27 based on the results of previous randomized trials28–31 and meta-analyses.32,33 Reduced gastrointestinal motility and constipation are common issues in patients with cardiovascular disease, owing to their advanced age and reduced physical activity. In patients with HF, impaired intestinal peristalsis in the edematous gut and reduced amounts of water in the gut induced by diuretics contribute to reduced gastrointestinal motility.34 Hence, it may be relatively common to use Daikenchuto in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Yokukansan is useful for improving behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD),35 according to previous randomized trials36,37 and meta-analyses.38,39 Although the effects of Yokukansan on the occurrence of delirium in patients without a prior diagnosis of dementia remain unknown, physicians’ experiences with Yokukansan for BPSD may have led to its use for delirium or BPSD-like symptoms in patients with cardiovascular disease. This may be related to the fact that up to 20% of patients with acute HF developed delirium and had higher mortality and morbidity rates than those who did not.40,41

Of the remaining top 5 Kampo medicines identified in the present study, Shakuyakukanzoto is effective against muscle cramps,42 and Rikkunshito is considered useful for improving functional dyspepsia, appetite loss, and upper gastrointestinal symptoms.43,44 In animal experimental models, Goreisan has been reported to have an aquaretic effect with lower risks of renal dysfunction and electrolyte abnormalities compared with loop diuretics.45,46 However, although Goreisan is reportedly effective in the prevention of postoperative recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma47,48 and the treatment of postoperative abdominal lymphedema,49 currently there is no evidence of clinical benefits in patients with cardiovascular disease from randomized trials. Thus, the results of the ongoing large-scale GOREISAN for heart failure (GOREISAN-HF) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04691700) are awaited.50

A recent review reported that there is little clinical evidence for the effectiveness of Kampo medicine in patients with HF.18 Importantly, no study to date has demonstrated that the use of Kampo medication is associated with an improved prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute cardiovascular disease. Accordingly, it is considered rare to administer Kampo medicines for the direct treatment of cardiovascular disease; rather, they are likely to be used to relieve non-cardiac symptoms that often coexist with cardiovascular diseases, especially in older patients. Nonetheless, considering the expected mechanisms elucidated from experimental data, Kampo medicines may improve symptoms in patients with cardiovascular diseases and possibly lead to an improvement in their health-related quality of life, which is one of the major goals in the management of cardiovascular diseases in the relevant guidelines.51,52 Therefore, future studies are needed to assess and compare the prognosis and patient-reported outcomes between patients with cardiovascular disease who receive Kampo medicine and those who do not.

Changes in Kampo Medicine Practice Patterns in Cardiovascular Medicine

Our data demonstrated that Kampo medications were initiated earlier and used more frequently during hospitalization (i.e., a larger proportion of days covered by Kampo use). In addition, the frequency of Kampo use increased in all hospitals, despite hospital variations in Kampo use. These findings suggest that more physicians and hospitals have become comfortable using Kampo in recent years. Although, empirically, Kampo medicines have been considered safe, with a low risk of adverse events, they are not free from adverse events. Kampo medicines may cause drug eruptions, liver injury, sympathomimetic symptoms (induced by ephedra), and pseudoaldosteronism (induced by licorice).53 In this regard, it should be noted that the proportion of patients continuing Kampo medicines after discharge declined over the years (from 57.9% in 2010 to 39.4% in 2021), suggesting an increased temporary use of Kampo medicines. This finding may reflect physicians’ concerns regarding the risks related to the long-term use of Kampo medicines. Although an increasing number of clinical trials on Kampo medicines have been conducted to date,11 most are based on small sample sizes, making it challenging to detect clinically important adverse events. Therefore, large-scale studies are warranted to examine the efficacy and safety of Kampo medications.

Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, the DPC database lacked data on the reasons/indications for Kampo use. Second, the present study could not examine the effectiveness of Kampo medications on the outcomes of cardiovascular diseases because it was based on analysis of observational data, in which unmeasured factors often act as confounders in assessing the causal relationship between treatment and outcomes. Third, because the data used in the present study was for Japanese inpatients, with Kampo medicines approved for use under the national medical insurance coverage, our results cannot be generalized to clinical settings in other countries. Nevertheless, our findings suggest the need for CAM for patients with cardiovascular diseases in clinical practice in Japan, similar to the scenario noted in other countries.6,7

Conclusions

This nationwide cohort study showed that Kampo medications are increasingly being used in acute care settings for cardiovascular diseases. Considering the current situation in which Kampo is used despite the lack of robust evidence and guideline recommendations, future pharmacoepidemiological studies on Kampo medicines are needed to establish evidence for the use of Kampo medicine in patients with acute cardiovascular disease.

Sources of Funding

T.I. received a grant from the Japan Kampo Medicines Manufacturers Association (Grant on Health Economics Research, 2023). H.Y. received grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan (Grant no. 23AA2003 and 22AA2003). The funding sources had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures

T.I., N.M., and T.J. were affiliated with the Department of Health Services Research. A.M. is affiliated with the Department of Health Services Research, which is a cooperative program between The University of Tokyo and Tsumura & Company. A.O. is affiliated with the Department of Prevention of Diabetes and Lifestyle-Related Diseases, which is a cooperative program between The University of Tokyo and the Asahi Mutual Life Insurance Company. Tsumura & Company and the Asahi Mutual Life Insurance Company played no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

IRB Information

The Institutional Review Board of The University of Tokyo approved this study and waived the requirement for informed consent from individual patients because all patient data were anonymized and deidentified (Approval no. 3501-(5); May 19, 2021).

Data Availability

The data used in the present study are not publicly available owing to contracts with the hospitals that provide data to the database.

Supplementary Files

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-23-0770

References

- 1.

Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76: 2982–3021.

- 2.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Vital statistics 2019 [in Japanese]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/kakutei19/ (accessed February 9, 2024).

- 3.

Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. Estimates of national medical care expenditure 2021 [in Japanese]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-iryohi/19/dl/data.pdf (accessed February 9, 2024).

- 4.

Kuwabara M, Mori M, Komoto S. Japanese national plan for promotion of measures against cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2021; 143: 1929–1931.

- 5.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924151536 (accessed February 9, 2024).

- 6.

Rabito MJ, Kaye AD. Complementary and alternative medicine and cardiovascular disease: An evidence-based review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013; 2013: 672097.

- 7.

Chow SL, Bozkurt B, Baker WL, Bleske BE, Breathett K, Fonarow GC, et al. Complementary and alternative medicines in the management of heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023; 147: e4–e30.

- 8.

Harris PE, Cooper KL, Relton C, Thomas KJ. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: A systematic review and update. Int J Clin Pract 2012; 66: 924–939.

- 9.

Motoo Y, Yukawa K, Arai I, Hisamura K, Tsutani K. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Japan: A cross-sectional internet survey using the Japanese version of the international complementary and alternative medicine questionnaire. JMA J 2019; 2: 35–46.

- 10.

Fuyuno I. Japan: Will the sun set on Kampo? Nature 2011; 480: S96.

- 11.

Arai I. Clinical studies of traditional Japanese herbal medicines (Kampo): Need for evidence by the modern scientific methodology. Integr Med Res 2021; 10: 100722.

- 12.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. The Statistics of Production by Pharmaceutical Industry 2021 [in Japanese]. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?tclass=000001160462&cycle=7&year=20210 (accessed February 9, 2024).

- 13.

Yasunaga H. Real world data in Japan: Chapter II the Diagnosis Procedure Combination database. Ann Clin Epidemiol 2019; 1: 76–79.

- 14.

Yamana H, Moriwaki M, Horiguchi H, Kodan M, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Validity of diagnoses, procedures, and laboratory data in Japanese administrative data. J Epidemiol 2017; 27: 476–482.

- 15.

Yamana H, Konishi T, Yasunaga H. Validation studies of Japanese administrative health care data: A scoping review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2023; 32: 705–717.

- 16.

Nakai M, Iwanaga Y, Sumita Y, Kanaoka K, Kawakami R, Ishii M, et al. Validation of acute myocardial infarction and heart failure diagnoses in hospitalized patients with the nationwide claim-based JROAD-DPC database. Circ Rep 2021; 3: 131–136.

- 17.

Jann B. Plotting regression coefficients and other estimates. Stata Journal 2014; 14: 708–737.

- 18.

Yaku H, Kaneda K, Kitamura J, Kato T, Kimura T. Kampo medicine for the holistic approach to older adults with heart failure. J Cardiol 2022; 80: 306–312.

- 19.

Jurgens CY, Lee CS, Aycock DM, Masterson Creber R, Denfeld QE, DeVon HA, et al. State of the science: The relevance of symptoms in cardiovascular disease and research: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022; 146: e173–e184.

- 20.

Ezaki H, Ayaori M, Sato H, Maeno Y, Taniwaki M, Miyake T, et al. Effects of mokuboito, a Japanese Kampo medicine, on symptoms in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure: A prospective randomized pilot study. J Cardiol 2019; 74: 412–417.

- 21.

Gautam M, Izawa A, Saigusa T, Yamasaki S, Motoki H, Tomita T, et al. The traditional Japanese medicine (Kampo) boiogito has a dual benefit in cardiorenal syndrome: A pilot observational study. Shinshu Med J 2014; 62: 89–97.

- 22.

Miho E, Iwai-Takano M, Saitoh H, Watanabe T. Acute and chronic effects of mokuboito in a patient with heart failure due to severe aortic regurgitation. Fukushima J Med Sci 2019; 65: 61–67.

- 23.

Kakeshita K, Imamura T, Onoda H, Kinugawa K. Impact of Goreisan upon aquaporin-2-incorporated aquaresis system in patients with congestive heart failure. CEN Case Rep 2023; 12: 73–77.

- 24.

Medical Education Model Core Curriculum Committee and Medical Education Model Core Curriculum Expert Research Committee. Model Core Curriculum for medical education in Japan: AY 2016 revision. https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20230323-mxt_igaku-000028108_00005.pdf (accessed February 9, 2024).

- 25.

Motoo Y, Seki T, Tsutani K. Traditional Japanese medicine, Kampo: Its history and current status. Chin J Integr Med 2011; 17: 85–87.

- 26.

Yamana H, Ono S, Michihata N, Jo T, Yasunaga H. Outpatient prescriptions of Kampo formulations in Japan. Intern Med 2020; 59: 2863–2869.

- 27.

Namiki T, Hoshino T, Egashira N, Kogure T, Endo M, Homma M. A review of frequently used Kampo prescriptions part 1: Daikenchuto. Tradit Kampo Med 2022; 9: 151–179, doi:10.1002/tkm2.1321.

- 28.

Endo S, Nishida T, Nishikawa K, Nakajima K, Hasegawa J, Kitagawa T, et al. Dai-kenchu-to, a Chinese herbal medicine, improves stasis of patients with total gastrectomy and jejunal pouch interposition. Am J Surg 2006; 192: 9–13.

- 29.

Yoshikawa K, Shimada M, Wakabayashi G, Ishida K, Kaiho T, Kitagawa Y, et al. Effect of Daikenchuto, a traditional Japanese herbal medicine, after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 571–578.

- 30.

Manabe N, Camilleri M, Rao A, Wong BS, Burton D, Busciglio I, et al. Effect of daikenchuto (TU-100) on gastrointestinal and colonic transit in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2010; 298: G970–G975.

- 31.

Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Tanaka N. Effect of traditional Japanese medicine, Daikenchuto (TJ-100) in patients with chronic constipation. Gastroenterol Res 2010; 3: 151–155.

- 32.

Ishizuka M, Shibuya N, Nagata H, Takagi K, Iwasaki Y, Hachiya H, et al. Perioperative administration of traditional Japanese herbal medicine daikenchuto relieves postoperative ileus in patients undergoing surgery for gastrointestinal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anticancer Res 2017; 37: 5967–5974.

- 33.

Hosaka M, Arai I, Ishiura Y, Ito T, Seki Y, Naito T, et al. Efficacy of daikenchuto, a traditional Japanese Kampo medicine, for postoperative intestinal dysfunction in patients with gastrointestinal cancers: Meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 2019; 24: 1385–1396.

- 34.

Ishiyama Y, Hoshide S, Mizuno H, Kario K. Constipation-induced pressor effects as triggers for cardiovascular events. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019; 21: 421–425.

- 35.

Yamaguchi H, Yoshino T, Oizumi H, Arita R, Nogami T, Takayama S. A review of frequently used Kampo prescriptions. Part 3. Yokukansan. Traditional & Kampo Medicine 2023; 10: 197–223, doi:10.1002/tkm2.1386.

- 36.

Iwasaki K, Satoh-Nakagawa T, Maruyama M, Monma Y, Nemoto M, Tomita N, et al. A randomized, observer-blind, controlled trial of the traditional Chinese medicine yi-gan san for improvement of behavioral and psychological symptoms and activities of daily living in dementia patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 248–252.

- 37.

Mizukami K, Asada T, Kinoshita T, Tanaka K, Sonohara K, Nakai R, et al. A randomized cross-over study of a traditional Japanese medicine (Kampo), yokukansan, in the treatment of the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2009; 12: 191–199.

- 38.

Matsuda Y, Kishi T, Shibayama H, Iwata N. Yokukansan in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hum Psychopharmacol 2013; 28: 80–86.

- 39.

Matsunaga S, Kishi T, Iwata N. Yokukansan in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 54: 635–643.

- 40.

Honda S, Nagai T, Sugano Y, Okada A, Asaumi Y, Aiba T, et al. Prevalence, determinants, and prognostic significance of delirium in patients with acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2016; 222: 521–527.

- 41.

Uthamalingam S, Gurm GS, Daley M, Flynn J, Capodilupo R. Usefulness of acute delirium as a predictor of adverse outcomes in patients >65 years of age with acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108: 402–408.

- 42.

Ota K, Fukui K, Nakamura E, Oka M, Ota K, Sakaue M, et al. Effect of shakuyaku-kanzo-to in patients with muscle cramps: A systematic literature review. J Gen Fam Med 2020; 21: 56–62.

- 43.

Ko SJ, Park J, Kim MJ, Kim J, Park JW. Effects of the herbal medicine Rikkunshito, for functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 36: 64–74.

- 44.

Tominaga K, Sakata Y, Kusunoki H, Odaka T, Sakurai K, Kawamura O, et al. Rikkunshito simultaneously improves dyspepsia correlated with anxiety in patients with functional dyspepsia: A randomized clinical trial (the DREAM study). Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 30: e13319.

- 45.

Kurita T, Nakamura K, Tabuchi M, Orita M, Ooshima K, Higashino H. Effects of gorei-san: A traditional Japanese Kampo medicine, on aquaporin 1, 2, 3, 4 and V2R mRNA expression in rat kidney and forebrain. J Med Sci 2010; 11: 30–38.

- 46.

Ohnishi N, Nagasawa K, Yokoyama T. The verification of regulatory effects of Kampo formulations on body fluid using model mice. J Tradit Med 2000; 17: 131–136.

- 47.

Yasunaga H. Effect of Japanese herbal Kampo medicine Goreisan on reoperation rates after burr-hole surgery for chronic subdural hematoma: Analysis of a national inpatient database. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015; 2015: 817616.

- 48.

Goto S, Kato K, Yamamoto T, Shimato S, Ohshima T, Nishizawa T. Effectiveness of Goreisan in preventing recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma. Asian J Neurosurg 2018; 13: 370–374.

- 49.

Komiyama S, Takeya C, Takahashi R, Yamamoto Y, Kubushiro K. Feasibility study on the effectiveness of Goreisan-based Kampo therapy for lower abdominal lymphedema after retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy via extraperitoneal approach. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015; 41: 1449–1456.

- 50.

Yaku H, Kato T, Morimoto T, Kaneda K, Nishikawa R, Kitai T, et al. Rationale and study design of the GOREISAN for heart failure (GOREISAN-HF) trial: A randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J 2023; 260: 18–25.

- 51.

Makita S, Yasu T, Akashi YJ, Adachi H, Izawa H, Ishihara S, et al. JCS/JACR 2021 guideline on rehabilitation in patients with cardiovascular disease. Circ J 2022; 87: 155–235.

- 52.

Tsutsui H, Isobe M, Ito H, Ito H, Okumura K, Ono M, et al. JCS 2017/JHFS 2017 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Digest version. Circ J 2019; 83: 2084–2184.

- 53.

Shimada Y. Adverse effects of Kampo medicines. Intern Med 2022; 61: 29–35.