Abstract

Background: The Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) has been incorporated into preoperative assessment guidelines and is used for simple preoperative screening; however, validation studies within large populations are limited. Moreover, although sex differences in perioperative risk are recognized, their effect on the performance of the RCRI remains unclear. Therefore, in this study we evaluated whether sex differences exist in the risks within the strata classified by the RCRI.

Methods and Results: The Japan Medical Data Center database based on claim and health examination data in Japan between January 2005 and April 2021 was used. A total of 161,359 noncardiac surgeries performed during hospitalization were analyzed. The main outcome was the 30-day risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. Although there was no significant sex difference among those with an RCRI ≥1, males had a significant hazard rate (1.32 [95% confidence interval, 1.03–1.68]) of postoperative events in the low-risk group with an RCRI of 0. However, this significant difference was not detected in the population excluding those who underwent breast and gynecological surgeries.

Conclusions: The RCRI achieved reasonable risk stratification in validation using Japanese real-world data regardless of sex. Although further detailed analysis is necessary to determine the sex differences, the validity of using the RCRI for screening purposes is supported at this stage.

The number of surgical procedures and the importance of collateral complications are increasing worldwide.1,2 Stratification of the risk of postoperative cardiovascular complications in noncardiac surgeries and the scope for intervention are important topics, and several clinical guidelines, such as those by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association,3 European Society of Cardiology,4 Canadian Cardiovascular Society,5 and Japanese Circulation Society,6 have provided recommendations for specific assessments and interventions. The incidence of postoperative cardiovascular events is influenced by patient-specific factors and inherent risks associated with the surgical procedure itself.7–11 Consequently, it is essential to conduct individualized preoperative assessments and stratify the risk of each patient accordingly.

A detailed assessment of the risk of perioperative cardiovascular complications is complex because perioperative risk involves both the risk of the procedure itself and patient factors.12,13 Many attempts have been made to stratify these factors in clinical practice, and many assessment tools have been developed.1,14–20 Among these, the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)16 has been a long-standing tool in clinical practice for stratifying the risk of perioperative cardiovascular events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgeries.21 Although imperfections in predictive performance have been reported, including decreased accuracy for vascular surgery,14,17,20 the RCRI has been integrated into preoperative guidelines for noncardiac surgeries and serves as a risk evaluation algorithm.3–6 It stratifies patients based on the likelihood of a composite outcome of myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest or death by assigning scores to 6 independent predictors. Patients with a score of 0 who do not have any of these 6 risk factors (elevated-risk surgery, history of ischemic heart disease, history of congestive heart failure, history of cerebrovascular disease, history of diabetes requiring preoperative insulin use, and preoperative creatinine level >2 mg/dL) are identified by the RCRI as low risk for cardiac complications.2,16,22–33

Recently, the importance of recognizing sex biases in the cardiovascular field is increasingly recognized.34 Sex differences in cardiovascular risk exist in various ways, and an understanding of the clinical significance of these biases is important.35–41 It is important to assess bias with respect to the RCRI because it is currently used as a risk assessment tool in clinical practice. Previous studies investigating sex differences in the incidence of postoperative events among patients undergoing noncardiac surgeries have typically observed a higher postoperative risk in males than in females.42–45 However, when using the RCRI for risk stratification, the extent to which risk is influenced by sex within each stratified patient group remains unclear. Consequently, in this study we aimed to ascertain the risk stratification capability of the RCRI and the magnitude of sex bias within patient groups stratified by risk in the evaluation of the postoperative risk of noncardiac surgeries.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We used the Japan Medical Data Center (JMDC) claims database, which contains information on medical claims and health examinations in Japan.46–49 The database, which is accessible for purchase from the JMDC, encompasses data on approximately 11.6 million individuals from January 2005 to April 2021. It comprises diagnostic information based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), prescription data according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system, medical practice details based on the receipt of electronic processing codes, and results of specific medical examinations.

For this analysis, codes corresponding to noncardiac surgeries were extracted from the medical practice data alongside classification codes indicating surgery (K-codes), resulting in 3,797,257 codes. From these, only the codes recorded during hospitalization were selected. The selection was further refined to surgeries in which general or spinal anesthesia was administered on the same day. The analysis was limited to individuals aged ≥18 years. When multiple K-codes were recorded on the same day, the code with the highest reimbursement score was retained as the primary surgery, and duplicate K-codes on the same day were excluded. Patients with no recorded postoperative data were excluded from the study. The final study included patients with creatinine levels measured during physical examination within 1 year prior to surgery.

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Although this study used anonymized data and was outside the scope of the guidelines for research involving human subjects in Japan, it was conducted after registration with the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital (Approval No. 2024105NIe).

Measurements

In this study, K-codes, which represent the classification numbers of electronic receipt processing codes in Japan, were used to identify noncardiac and cardiac surgeries, addition codes, and blood transfusion codes that were excluded from the analysis. General and spinal anesthesia administrations were identified from the electronic receipt processing codes. Previous ischemic heart disease was defined as ICD-10 codes I20–I25 or multiple prescriptions for abortive nitroglycerin prior to surgery. A history of stroke was defined according to ICD-10 codes I60–I64 and G459. A history of heart failure was determined using ICD-10 codes I50 and I110. Diabetes requiring insulin administration was defined as the coexistence of ICD-10 codes E10–E14 and ATC code A10A in the prescription information. High-risk surgeries were identified using codes corresponding to abdominal, thoracic, and vascular surgeries performed above the inguinal region. Creatinine levels >2.0 mg/dL were established using values from physical examinations conducted within 1 year prior to surgery. Patients in whom creatinine levels were not recorded within the year prior to surgery were excluded from the analysis. The RCRI was calculated based on these items. In line with previous validation studies, we divided the nonsurgical cases into 4 groups based on the RCRI (0, 1, 2, and ≥3).50

For detailed disease definitions used in the sensitivity analysis, a combination of ICD-10 and medical practice codes was used with reference to validation studies.51–53 Specifically, previous ischemic heart disease was defined using ICD-10 codes I20–I23 with same-day percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting performed within 7 days. Additionally, cases in which the patients were administered antiplatelet agents within 2 days, in conjunction with ICD-10 codes I20–I23, were also classified as a history of ischemic heart disease. Heart failure was defined using ICD-10 codes I50 and I110, combined with the administration of intravenous diuretics within 2 days of the diagnosis. Cerebral infarction was defined using ICD-10 codes I60, I61, I63, G45.8, and G45.9, in combination with a computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging evaluation performed on the same day as the diagnosis.

Sensitivity Analysis

Breast and gynecological surgeries are procedures specific to females, with breast surgery, in particular, being associated with a low perioperative cardiovascular risk.54 In the sensitivity analysis, we evaluated a cohort that excluded breast and gynecological surgeries (sensitivity analysis 1). Additionally, a separate sensitivity analysis was performed on a cohort that excluded urological surgeries, alongside breast and gynecological surgeries (sensitivity analysis 2), as urologic procedures are predominantly specific to males. Similar analyses were conducted in a cohort utilizing a detailed history definition that integrated ICD-10 codes with medical procedure codes (sensitivity analyses 3–5). Additionally, similar analyses were conducted in a cohort utilizing a detailed history and outcome definition with ICD-10 codes and procedure codes (sensitivity analyses 6–8).

Outcomes

The outcome of this study was defined as the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within 30 days of surgery, based on ICD-10 codes: myocardial infarction (ICD-10 codes: I21–I22), heart failure (ICD-10 codes: I50 and I110), stroke (ICD-10 codes: I60–I64 and G459), arrest (ICD-10 code: I46), and death. Follow-up was defined as the period from the date of surgery to the date of death or the last recorded entry into the insurance database, whichever came first. For the sensitivity analysis using detailed disease definitions, the definitions of ischemic heart disease, heart failure, and stroke were combined with medical practice codes, following the methodology outlined in the Measurements section above.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are presented as percentages and were tested using the chi-square test. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation and tested using the Student’s t-test. Incidence rates were calculated per 100 persons over 30 days. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to the cumulative incidence plots, and the log-rank test was used for statistical testing. Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to calculate the hazard rate for males relative to females; in the Cox proportional hazards analysis, age was included in the model as an adjustment factor. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.3.

Results

Patients’ Characteristics and Outcomes

A total of 161,359 surgeries were included in the analysis (Figure 1, Table 1). MACE within 30 days after surgery occurred in 987 cases (Table 2). The mean age of the patients at surgery was approximately 48 years. Male patients had a significantly higher mean age, body mass index, and serum creatinine levels. Significant sex differences were observed in the number of breast, gynecological, and urological surgeries. Additionally, significant sex differences were noted in the occurrence of events in abdominal, breast, and ear, nose, and throat/neck surgeries (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ Clinical Background Information

| Variables |

Overall |

Male |

Female |

P value |

| N |

161,359 |

90,382 |

70,977 |

|

| Age, mean (SD), years |

48.63 (11.29) |

50.22 (11.44) |

46.60 (10.75) |

<0.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 |

23.35 (3.89) |

24.14 (3.68) |

22.34 (3.91) |

<0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, mean (SD), μmol/L |

0.79 (0.52) |

0.91 (0.62) |

0.63 (0.27) |

<0.001 |

| Type of surgery (%) |

| Abdominal |

39,052 (24.2) |

29,606 (32.8) |

9,446 (13.3) |

<0.001 |

| Breast |

8,258 (5.1) |

96 (0.1) |

8,162 (11.5) |

|

| Dermatologic |

2,214 (1.4) |

1,599 (1.8) |

615 (0.9) |

|

| ENT/neck |

13,456 (8.3) |

9,149 (10.1) |

4,307 (6.1) |

|

| Gynecologic |

30,550 (18.9) |

2 (0.0) |

30,548 (43.0) |

|

| Neurological |

5,206 (3.2) |

3,323 (3.7) |

1,883 (2.7) |

|

| Ophthalmic |

834 (0.5) |

601 (0.7) |

233 (0.3) |

|

| Oral |

401 (0.2) |

332 (0.4) |

69 (0.1) |

|

| Orthopedic |

39,364 (24.4) |

27,948 (30.9) |

11,416 (16.1) |

|

| Plastic |

1,322 (0.8) |

713 (0.8) |

609 (0.9) |

|

| Thoracic |

5,172 (3.2) |

3,840 (4.2) |

1,332 (1.9) |

|

| Urologic |

13,818 (8.6) |

12,050 (13.3) |

1,768 (2.5) |

|

| Vascular |

1,712 (1.1) |

1,123 (1.2) |

589 (0.8) |

|

| History of ischemic heart disease (%) |

10,935 (6.8) |

7,809 (8.6) |

3,126 (4.4) |

<0.001 |

| History of congestive heart failure (%) |

9,249 (5.7) |

6,409 (7.1) |

2,840 (4.0) |

<0.001 |

| History of cerebrovascular disease (%) |

5,831 (3.6) |

4,018 (4.4) |

1,813 (2.6) |

<0.001 |

| Preoperative treatment with insulin (%) |

4,147 (2.6) |

3,266 (3.6) |

881 (1.2) |

<0.001 |

| Preoperative creatinine >2 mg/dL (%) |

718 (0.4) |

616 (0.7) |

102 (0.1) |

<0.001 |

| Elevated-risk surgery (%) |

44,850 (27.8) |

33,898 (37.5) |

10,952 (15.4) |

<0.001 |

| RCRI group (%) |

| 0 |

100,871 (62.5) |

46,605 (51.6) |

54,266 (76.5) |

<0.001 |

| 1 |

48,957 (30.3) |

34,768 (38.5) |

14,189 (20.0) |

|

| 2 |

8,534 (5.3) |

6,426 (7.1) |

2,108 (3.0) |

|

| ≥3 |

2,997 (1.9) |

2,583 (2.9) |

414 (0.6) |

|

BMI, body mass index; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; RCRI, Revised Cardiac Risk Index; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Development of MACE Within 30 Days After Surgery

| |

Overall |

Male |

Female |

| Event (−) |

Event (+) |

Event (−) |

Event (+) |

Event (−) |

Event (+) |

| Total (n) |

160,372 |

987 |

89,705 |

677 |

70,667 |

310 |

| RCRI group (%) |

| 0 |

100,590 (62.7) |

281 (28.5) |

46,448 (51.8) |

157 (23.2) |

54,142 (76.6) |

124 (40.0) |

| 1 |

48,576 (30.3) |

381 (38.6) |

34,501 (38.5) |

267 (39.4) |

14,075 (19.9) |

114 (36.8) |

| 2 |

8,338 (5.2) |

196 (19.9) |

6,281 (7.0) |

145 (21.4) |

2,057 (2.9) |

51 (16.5) |

| ≥3 |

2,868 (1.8) |

129 (13.1) |

2,475 (2.8) |

108 (16.0) |

393 (0.6) |

21 (6.8) |

MACE, major adverse cardiac events; RCRI, Revised Cardiac Risk Index.

Survival Analysis

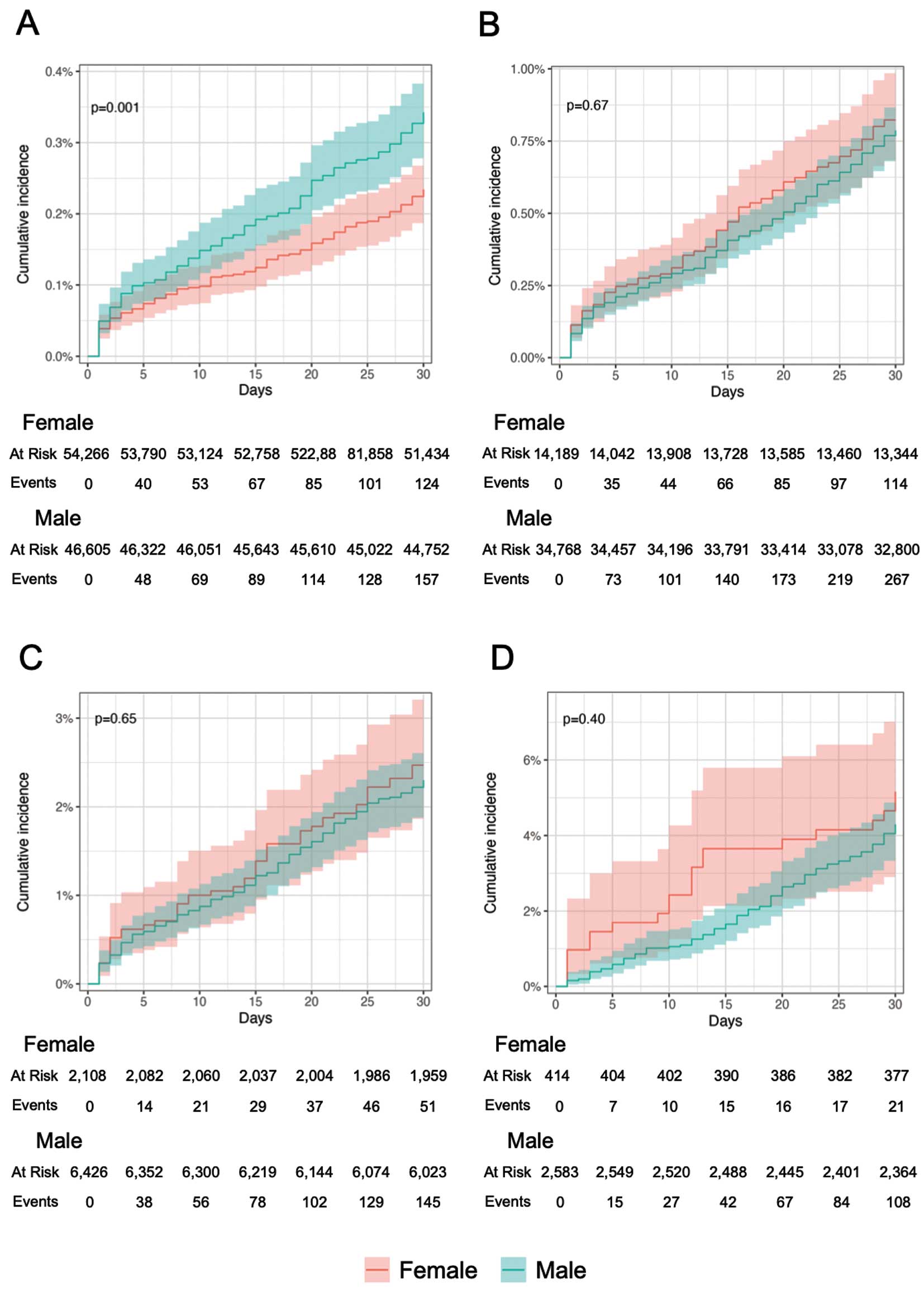

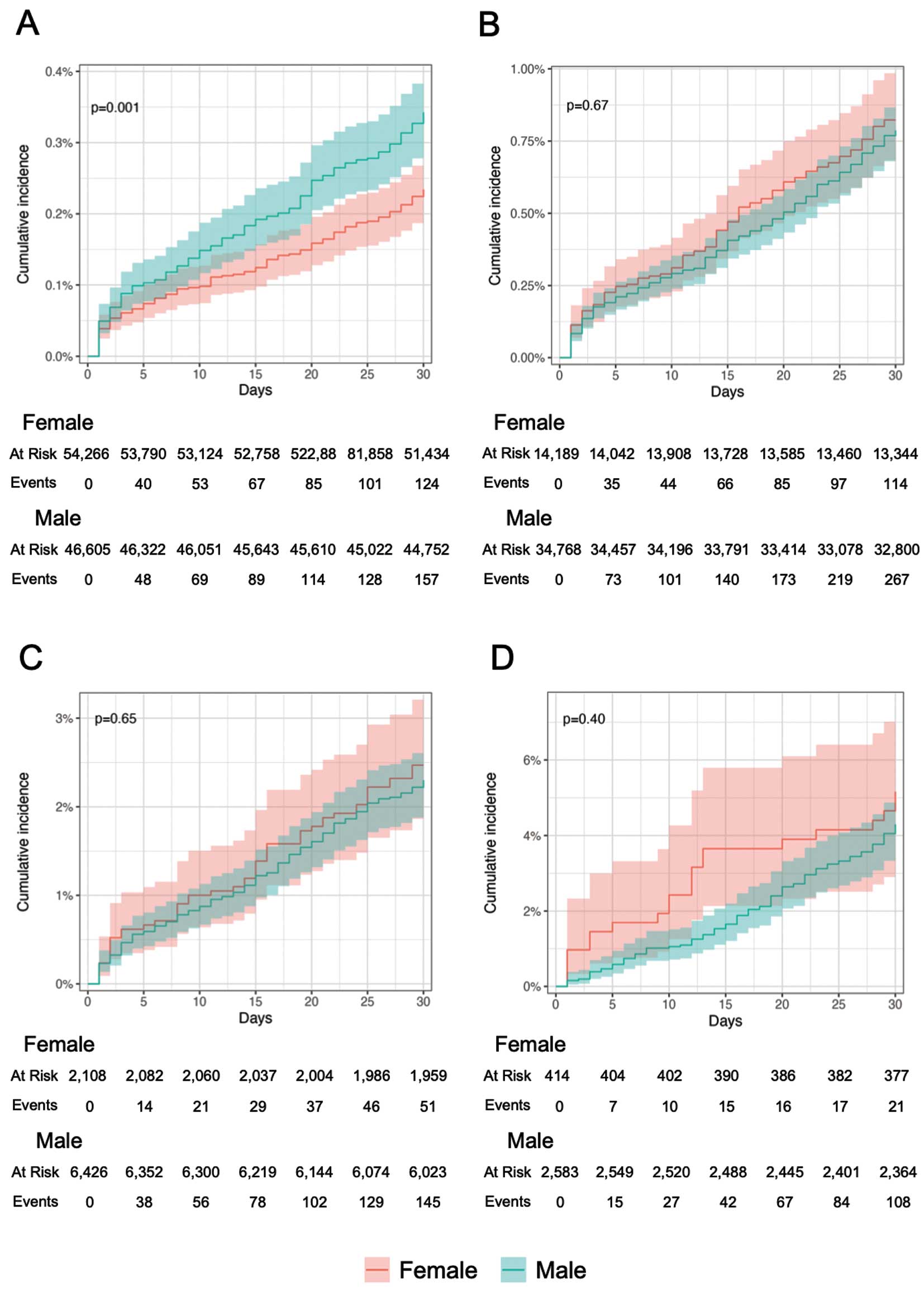

The overall MACE occurrence after surgery analyzed by the RCRI showed that significant stratification was achieved when the cumulative event occurrence was evaluated by the cumulative incidence plots with the Kaplan-Meier method (Figure 2). Similar stratification was achieved in the calculation of event rates, with 4.50 MACE events (per 100-person, month) in the group with an RCRI ≥3 (Table 3). An RCRI of 0 showed a significantly higher incidence of MACE in males than in females (Figure 3, Table 4). There was no significant difference in event rates by sex for groups other than those with an RCRI of 0. In the Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, the hazard rate for males compared with females was significantly higher only in the group with an RCRI of 0 (Table 5).

Table 3.

Overall MACE Incidence After Surgery Stratified by RCRI

| RCRI |

N |

Event n (%) |

Incidence (events, per

100 person – 30 days) |

Incidence 95% CI |

| All |

161,359 |

987 (0.6) |

0.63 |

0.59–0.67 |

| 0 |

100,871 |

281 (0.3) |

0.29 |

0.25–0.32 |

| 1 |

48,957 |

381 (0.8) |

0.80 |

0.72–0.89 |

| 2 |

8,534 |

196 (2.3) |

2.38 |

2.06–2.73 |

| ≥3 |

2,997 |

129 (4.3) |

4.50 |

3.75–5.34 |

CI, confidence interval; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; RCRI, Revised Cardiac Risk Index.

Table 4.

MACE Incidence After Surgery Stratified by Sex and RCRI

| RCRI |

Male |

Female |

P value |

| N |

Event, n

(%) |

Incidence (events,

per 100 person

– 30 days) |

Incidence,

95% CI |

N |

Event, n

(%) |

Incidence (events,

per 100 person

– 30 days) |

Incidence,

95% CI |

| All |

90,382 |

677 (0.7) |

0.77 |

0.71–0.83 |

70,977 |

310 (0.4) |

0.45 |

0.40–0.50 |

<0.001 |

| 0 |

46,605 |

157 (0.3) |

0.34 |

0.29–0.40 |

54,266 |

124 (0.2) |

0.24 |

0.20–0.28 |

<0.005 |

| 1 |

34,768 |

267 (0.8) |

0.79 |

0.70–0.89 |

14,189 |

114 (0.8) |

0.83 |

0.68–1.00 |

0.67 |

| 2 |

6,426 |

145 (2.3) |

2.33 |

1.97–2.75 |

2,108 |

51 (2.4) |

2.51 |

1.87–3.30 |

0.65 |

| ≥3 |

2,583 |

108 (4.2) |

4.36 |

3.58–5.27 |

414 |

21 (5.1) |

5.34 |

3.31–8.17 |

0.40 |

Abbreviations as in Table 3.

Table 5.

Age-Adjusted Hazard Rate for Males Relative to Females Based on Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis

| RCRI |

Age-adjusted

HR |

Age-adjusted

HR 95% CI |

P value for

interaction |

| All |

1.30 |

1.06–1.59 |

<0.005 |

| 0 |

1.32 |

1.03–1.68 |

|

| 1 |

0.94 |

0.75–1.17 |

|

| 2 |

0.90 |

0.65–1.24 |

|

| ≥3 |

0.83 |

0.52–1.33 |

|

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; RCRI, Revised Cardiac Risk Index.

Sensitivity Analysis

Details of the cohorts in the sensitivity analysis are shown in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. The results of analysis excluding sex-specific surgeries (sensitivity analyses 1 and 2) demonstrated that although the stratification performance of the RCRI remained consistent, there were no significant differences in incidence or significant hazard ratios between sex across any of the risk strata (Supplementary Tables 4–7). Similarly, the significant sex differences observed in the RCRI 0 group within the cohort with detailed history definition (sensitivity analysis 3) were not detected in the cohort excluding sex-specific surgeries (sensitivity analyses 4 and 5). In the analysis of all surgical cases with the cohort with detailed history and outcome definition (sensitivity analysis 6), the adjusted hazard ratios were predominantly >1 for both the RCRI 0 and 1 groups. However, in separate analyses excluding sex-specific surgeries (sensitivity analyses 7 and 8), the significance of the hazard ratio by sex was no longer observed in the RCRI 0 group, but remained significant in the RCRI 1 group.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the validity of the RCRI and investigated the effect of sex differences using a large dataset of claims data from Japan. This study was a descriptive analysis of whether sex differences existed within strata defined according to the RCRI, using data obtained from real-world Japanese patients. Although males are known to have a higher incidence of MACE after noncardiac surgeries,55 our main analysis suggested that the RCRI achieved appropriate risk stratification, and that the sex difference was limited to the group with an RCRI of 0. Although the RCRI was published more than 20 years ago,16 it continues to be utilized for screening in clinical practice owing to its simplicity.3–6 In our validation, the number of surgeries with an RCRI of 0 accounted for the majority of surgeries in the analysis. Considering that >200 million surgeries are performed annually worldwide,56 and that the group with an RCRI of 0 represents more than half of all noncardiac surgeries, the sex difference in incidence rates in this group is likely to produce a fairly large difference in the number of postoperative MACE events. However, in the cohort excluding sex-specific surgeries, a significant sex difference was not observed in the low-risk group, suggesting that the previously identified significant difference may be attributable to the sex-specific nature of the surgical procedures. The findings after excluding sex-specific surgeries were replicated in the cohort where a detailed history definition was applied to improve the positive predictive value of disease identification in the sensitivity analysis. Conversely, in the sensitivity analysis with the cohort with detailed history and outcome definition, the age-adjusted hazard ratio remained significantly greater than 1 in the group with an RCRI of 1, even after the exclusion of sex-specific surgeries. Consequently, it remains inconclusive whether a significant sex difference with a clinically significant effect exists within this group. Based on the incidence of events observed in both the main and sensitivity analyses for the RCRI 1 group (Tables 3,4, Supplementary Tables 4,5), it is unlikely that any such difference would have a clinically significant effect that would undermine the utility of screening. However, further rigorous validation using diverse databases will be required to enhance the robustness of the RCRI 1 group in confirming the absence of clinically meaningful sex differences.

The incidence rate in the population analyzed in this study was slightly lower than that reported in previous validation studies.32,33,50 The JMDC database used in this study was constructed based on health insurance claims and health checkup data provided by insurers; therefore, it does not include populations with different insurance systems. A critical feature of the JMDC database is that older adults aged ≥75 years in Japan are not included because of the different insurance systems in Japan. Additionally, it is important to note that the JMDC data was primarily sourced from corporate health insurance associations, which predominantly cover young to middle-aged workers and their families. These demographic limitations may affect the generalizability of the analysis results.57 Because risk stratification by the RCRI was adequately reproduced in the population analyzed in this study and the deviation from previously reported postoperative event rates was small, the results of sex bias obtained in this study may have a certain degree of reliability, despite the limitation of being a retrospective cohort study. However, this study does not entirely rule out the possibility of sex differences within the RCRI framework. To determine the presence of such differences, further detailed analysis of specific groups will be necessary in future research.

Study Limitations

This was a retrospective study with several limitations, one of which was that due to the nature of the database, the surgeries analyzed did not include cases in which the patient’s age at the time of surgery was ≥75 years. Second, because the study was based on claims data, it is impossible to ascertain whether an event occurred before or after the surgery on the day of the surgery; therefore, such events were not included as outcomes. Consequently, there may be a bias in this study regarding the occurrence of cardiovascular events due to these factors. Furthermore, the analysis relied on information recorded for reimbursement, which may introduce bias regarding the reflection of actual clinical conditions. Disease definitions based solely on ICD-10 codes may exhibit higher sensitivity but lower positive predictive values, whereas definitions combining ICD-10 codes with medical practice codes may enhance positive predictive values at the expense of sensitivity.51 Additionally, the definition of MACE by ICD10 codes has not been standardized, and there is a problem of variation among studies; this study is no exception to this problem.58 Third, creatinine values were based on periodic medical examinations within 1 year prior to surgery, and bias may exist. In addition, because a missing creatinine value indicates that the patient did not undergo a periodic medical examination within the past year, there may be a selection bias due to the exclusion of these cases from the analysis.

Conclusions

The validity of the RCRI and sex differences in the incidence of postoperative cardiovascular events were assessed using a large Japanese dataset. At this stage, no significant sex differences requiring clinical consideration were detected, and the results of this study support the validity of screening using the RCRI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the staff and graduate students of the Department of Healthcare Information Management at the University of Tokyo Hospital for providing an opportunity to continue this research. This work was supported by Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP) on “Integrated Health Care System” (Grant Number JPJ012425).

Disclosures

Y.K. belongs to the Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twin Development in Healthcare, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, which is an endowment department. However, the sponsors had no influence over the interpretation, writing, or publication of this work.

IRB Information

The Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital (Approval No. 2024105NIe).

Data Availability

The data underlying the findings of this study are provided by JMDC Inc. but were accessed under a license exclusively for this research; therefore, they are subject to restrictions and are not publicly available. For inquiries about accessing the dataset utilized in this study, please contact JMDC (https://www.jmdc.co.jp).

Supplementary Files

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-24-0846

References

- 1.

Alrezk R, Jackson N, Al Rezk M, Elashoff R, Weintraub N, Elashoff D, et al. Derivation and Validation of a Geriatric-Sensitive Perioperative Cardiac Risk Index. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6: e006648.

- 2.

Ahn J, Park JR, Min JH, Sohn J, Hwang S, Park Y, et al. Risk stratification using computed tomography coronary angiography in patients undergoing intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: 661–668.

- 3.

Thompson A, Fleischmann KE, Smilowitz NR, De Las Fuentes L, Mukherjee D, Aggarwal NR, et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/ACS/ASNC/HRS/SCA/SCCT/SCMR/SVM Guideline for perioperative cardiovascular management for noncardiac surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024; 150: e351–e442.

- 4.

Halvorsen S, Mehilli J, Cassese S, Hall TS, Abdelhamid M, Barbato E, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J 2022; 43: 3826–3924.

- 5.

Duceppe E, Parlow J, MacDonald P, Lyons K, McMullen M, Srinathan S, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines on perioperative cardiac risk assessment and management for patients who undergo noncardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol 2017; 33: 17–32.

- 6.

Hiraoka E, Tanabe K, Izuta S, Kubota T, Kohsaka S, Kozuki A, et al.; Japanese Society Joint, Working Group. JCS 2022 Guideline on perioperative cardiovascular assessment and management for non-cardiac surgery. Circ J 2023; 87: 1253–1237.

- 7.

International Surgical Outcomes Study group. Global patient outcomes after elective surgery: Prospective cohort study in 27 low-, middle- and high-income countries. Br J Anaesth 2016; 117: 601–609.

- 8.

Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, Pelosi P, Metnitz P, Spies C, et al.; European Surgical Outcomes Study (EuSOS) group for the Trials groups of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Mortality after surgery in Europe: A 7 day cohort study. Lancet 2012; 380: 1059–1065.

- 9.

Noordzij PG, Poldermans D, Schouten O, Bax JJ, Schreiner FAG, Boersma E. Postoperative mortality in The Netherlands: A population-based analysis of surgery-specific risk in adults. Anesthesiology 2010; 112: 1105–1115.

- 10.

Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1368–1375.

- 11.

Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, Kumbhani DJ; Participants in the VA National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg 2005; 242: 326–323.

- 12.

Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative acute myocardial infarction associated with non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 2409–2417.

- 13.

Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Ramakrishna H, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with noncardiac surgery. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2: 181–187.

- 14.

Goldman L, Caldera DL, Nussbaum SR, Southwick FS, Krogstad D, Murray B, et al. Multifactorial index of cardiac risk in noncardiac surgical procedures. N Engl J Med 1977; 297: 845–850.

- 15.

Detsky AS, Abrams HB, McLaughlin JR, Drucker DJ, Sasson Z, Johnston N, et al. Predicting cardiac complications in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. J Gen Intern Med 1986; 1: 211–219.

- 16.

Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, Thomas EJ, Polanczyk CA, Cook EF, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100: 1043–1049.

- 17.

Gupta PK, Gupta H, Sundaram A, Kaushik M, Fang X, Miller WJ, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of cardiac risk after surgery. Circulation 2011; 124: 381–387.

- 18.

Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, Zhou L, Kmiecik TE, Ko CY, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator: A decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217: 833–842.e1–e3.

- 19.

Dakik HA, Chehab O, Eldirani M, Sbeity E, Karam C, Abou Hassan O, et al. A new index for pre-operative cardiovascular evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 3067–3078.

- 20.

Bertges DJ, Goodney PP, Zhao Y, Schanzer A, Nolan BW, Likosky DS, et al.; Vascular Study Group of New England. The Vascular Study Group of New England Cardiac Risk Index (VSG-CRI) predicts cardiac complications more accurately than the Revised Cardiac Risk Index in vascular surgery patients. J Vasc Surg 2010; 52: 674–683.

- 21.

Moraes CMTD, Corrêa LDM, Procópio RJ, Carmo GALD, Navarro TP. Tools and scores for general and cardiovascular perioperative risk assessment: A narrative review. Rev Col Bras Cir 2022; 49: e20223124.

- 22.

Sheth T, Chan M, Butler C, Chow B, Tandon V, Nagele P, et al.; Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography and Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation Study Investigators. Prognostic capabilities of coronary computed tomographic angiography before non-cardiac surgery: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2015; 350: h1907.

- 23.

Hirano Y, Takeuchi H, Suda K, Oyama T, Nakamura R, Takahashi T, et al. Clinical utility of the Revised Cardiac Risk Index in non-cardiac surgery for elderly patients: A prospective cohort study. Surg Today 2014; 44: 277–284.

- 24.

Davis C, Tait G, Carroll J, Wijeysundera DN, Beattie WS. The Revised Cardiac Risk Index in the new millennium: A single-centre prospective cohort re-evaluation of the original variables in 9,519 consecutive elective surgical patients. Can J Anaesth 2013; 60: 855–863.

- 25.

Wotton R, Marshall A, Kerr A, Bishay E, Kalkat M, Rajesh P, et al. Does the revised cardiac risk index predict cardiac complications following elective lung resection? J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 8: 220.

- 26.

Weber M, Luchner A, Manfred S, Mueller C, Liebetrau C, Schlitt A, et al. Incremental value of high-sensitive troponin T in addition to the revised cardiac index for peri-operative risk stratification in non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 853–862.

- 27.

Rao JY, Yeriswamy MC, Santhosh MJ, Shetty GG, Varghese K, Patil CB, et al. A look into Lee’s score: Peri-operative cardiovascular risk assessment in non-cardiac surgeries: Usefulness of revised cardiac risk index. Indian Heart J 2012; 64: 134–138.

- 28.

Leibowitz D, Planer D, Rott D, Elitzur Y, Chajek-Shaul T, Weiss A. Brain natriuretic peptide levels predict perioperative events in cardiac patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: A prospective study. Cardiology 2008; 110: 266–270.

- 29.

Maia PC, Abelha FJ. Predictors of major postoperative cardiac complications in a surgical ICU. Rev Port Cardiol 2008; 27: 321–328.

- 30.

Kumar R, McKinney WP, Raj G, Heudebert GR, Heller HJ, Koetting M, et al. Adverse cardiac events after surgery: Assessing risk in a veteran population. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 507–518.

- 31.

Fisher BW, Ramsay G, Majumdar SR, Hrazdil CT, Finegan BA, Padwal RS, et al. The ankle-to-arm blood pressure index predicts risk of cardiac complications after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2008; 107: 149–154.

- 32.

Sunny JC, Kumar D, Kotekar N, Desai N. Incidence and predictors of perioperative myocardial infarction in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery in a tertiary care hospital. Indian Heart J 2018; 70: 335–340.

- 33.

Yang HS, Hur M, Yi A, Kim H, Kim J. Prognostic role of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I and soluble suppression of tumorigenicity-2 in surgical intensive care unit patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Ann Lab Med 2018; 38: 204–211.

- 34.

Al Hamid A, Beckett R, Wilson M, Jalal Z, Cheema E, Obe DA, et al. Gender bias in diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review. Cureus 2024; 16: e54264.

- 35.

Lam CS, Arnott C, Beale AL, Chandramouli C, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kaye DM, et al. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J 2019; 40: 3859–3868c.

- 36.

Vitale C, Mendelsohn ME, Rosano GM. Gender differences in the cardiovascular effect of sex hormones. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009; 6: 532–542.

- 37.

Regitz-Zagrosek V, Kararigas G. Mechanistic pathways of sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev 2017; 97: 1–37.

- 38.

Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Kass Wenger N. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: What a difference a decade makes. Circulation 2011; 124: 2145–2154.

- 39.

Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten Haaf ME, Boersma E, Peters SA. Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis 2015; 241: 211–218.

- 40.

Shikuma A, Nishi M, Matoba S. Sex differences in process-of-care and in-hospital prognosis among elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 2024; 88: 1201–1207.

- 41.

Noma S, Kato K, Otsuka T, Nakao YM, Aoyama R, Nakayama A, et al.; the JROAD-DIVERSITY Investigators. Sex differences in cardiovascular disease-related hospitalization and mortality in Japan: Analysis of health records from a nationwide claim-based database, the Japanese Registry of All Cardiac and Vascular Disease (JROAD). Circ J 2024; 88: 1332–1342.

- 42.

Rucker D, Warkentin LM, Huynh H, Khadaroo RG. Sex differences in the treatment and outcome of emergency general surgery. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0224278.

- 43.

Peterson CY, Osen HB, Cao HST, Peter TY, Chang DC. The battle of the sexes: Women win out in gastrointestinal surgery. J Surg Res 2011; 170: e23–e28.

- 44.

Chu S, Li P, Han X, Liu L, Ye X, Wang J, et al. Differences in perioperative cardiovascular outcomes in elderly male and female patients undergoing intra-abdominal surgery: A retrospective cohort study. J Int Med Res 2021; 49: 0300060520985295.

- 45.

Grewal K, Wijeysundera DN, Carroll J, Tait G, Beattie WS. Gender differences in mortality following non-cardiovascular surgery: An observational study. Can J Anaesth 2012; 59: 255–262.

- 46.

Fujinaga J, Fukuoka T. A review of research studies using data from the administrative claims databases in Japan. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2022; 9: 543–550.

- 47.

Suto M, Sugiyama T, Imai K, Furuno T, Hosozawa M, Ichinose Y, et al. Studies of health insurance claims data in Japan: A scoping review. JMA J 2023; 6: 233–245.

- 48.

Nagai K, Tanaka T, Kodaira N, Kimura S, Takahashi Y, Nakayama T. Data resource profile: JMDC claims database sourced from health insurance societies. J Gen Fam Med 2021; 22: 118–127.

- 49.

Laurent T, Simeone J, Kuwatsuru R, Hirano T, Graham S, Wakabayashi R, et al. Context and considerations for use of two Japanese real-world databases in Japan: Medical Data Vision and Japanese Medical Data Center. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2022; 9: 175–187.

- 50.

Ford MK, Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN. Systematic Review: Prediction of perioperative cardiac complications and mortality by the Revised Cardiac Risk Index. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152: 26–35.

- 51.

Kanaoka K, Iwanaga Y, Okada K, Terasaki S, Nishioka Y, Nakai M, et al. Validity of diagnostic algorithms for cardiovascular diseases in Japanese health insurance claims. Circ J 2023; 87: 536–542.

- 52.

Shima D, Ii Y, Higa S, Kohro T, Hoshide S, Kono K, et al. Validation of novel identification algorithms for major adverse cardiovascular events in a Japanese claims database. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2021; 23: 646–655.

- 53.

Gon Y, Kabata D, Yamamoto K, Shintani A, Todo K, Mochizuki H, et al. Validation of an algorithm that determines stroke diagnostic code accuracy in a Japanese hospital-based cancer registry using electronic medical records. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017; 17: 157.

- 54.

El-Tamer MB, Ward BM, Schifftner T, Neumayer L, Khuri S, Henderson W. Morbidity and mortality following breast cancer surgery in women: National benchmarks for standards of care. Ann Surg 2007; 245: 665–671.

- 55.

Wu KY, Wang X, Youngson E, Gouda P, Graham MM. Sex differences in post-operative outcomes following non-cardiac surgery. Plos One 2023; 18: e0293638.

- 56.

Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, Haynes AB, Lipsitz SR, Berry WR, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: A modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet 2008; 372: 139–144.

- 57.

Ikegami N, Yoo B, Hashimoto H, Matsumoto M, Ogata H, Babazono A, et al. Japanese universal health coverage: Evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet 2011; 378: 1106–1115.

- 58.

Bosco E, Hsueh L, McConeghy KW, Gravenstein S, Saade E. Major adverse cardiovascular event definitions used in observational analysis of administrative databases: A systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021; 21: 241.