Abstract

Background: Relative hyperglycemia, as defined by the stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR), is linked to death and ischemic events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). As a modifiable factor, the association between SHR and bleeding risk after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) across different glycemic status remains unexplored.

Methods and Results: In this study, ACS patients treated with PCI were extracted from the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-Acute Coronary Syndrome (CCC-ACS) registry and the Tianjin Health and Medical Data Platform (THMDP). SHR was derived from admission fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c. Patients were classified as having diabetes mellitus, pre-diabetes mellitus (Pre-DM), or normal glucose regulation. The primary outcome was in-hospital major bleeding. Among the 33,265 patients in the CCC-ACS cohort, major bleeding was recorded for 437. A high SHR (>1.0) independently predicted major bleeding in the total cohort (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.24–1.83), with the highest risk in the Pre-DM group (aOR 1.98; 95% CI 1.34–2.92). These findings were externally validated among 23,423 patients with myocardial infarction in the THMDP cohort. Early guideline-directed medical therapy mitigated the bleeding risk associated with a high SHR.

Conclusions: In this study, a high SHR was an independent risk factor for in-hospital major bleeding after PCI, particularly in patients with Pre-DM. Further clinical trials are needed to explore SHR-targeted therapies in Pre-DM.

Stress-induced hyperglycemia (SIH) is a well-established risk factor for increased mortality among critically ill patients.1,2 SIH, as defined by a fasting blood glucose (FBG) level >125 mg/dL at admission,1 could be affected by chronic glucose levels, potentially leading to inaccurate assessments of SIH severity. Roberts et al. recently demonstrated that relative hyperglycemia, assessed by the stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) derived from FBG and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), provides a more accurate representation of SIH in critically ill patients than FBG alone.3 Emerging evidence shows that SHR is a risk factor for ischemic events and mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS),4–9 indicating that active in-hospital treatment for hypoglycemia may intervene in this reversible risk factor.

Over the past 20 years, ACS-related ischemic events have decreased significantly, largely due to the timely implementation of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and enhanced antithrombotic therapies.10–12 Concurrently, efforts have focused on preventing bleeding, the most common non-cardiac complication of PCI, which is linked to poor outcomes. Previous studies found that a higher SHR was associated with early hematoma enlargement in hemorrhagic stroke,13,14 likely due to increased superoxide production and plasma kallikrein activity,15,16 and that ACS patients undergoing PCI exhibit elevated bleeding risk.17–19 In addition, SIH has been associated with poorer outcomes in patients without diabetes mellitus (DM) than in those with DM patients.2,20 However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has specifically examined the relationship between SIH and major bleeding risk across different glycemic status. Furthermore, although DM is a key component in established bleeding risk prediction models,21 it remains unclear whether incorporating SHR into such models could enhance prognostic capacity.

In the present study, using data from the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-Acute Coronary Syndrome (CCC-ACS) project, a nationwide ACS registry, and the Tianjin Health and Medical Data Platform (THMDP), a real-world electronic health record-based platform, we examined and validated the relationship between SHR, major bleeding, and in-hospital death in ACS patients after PCI, stratified by glycemic status.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This retrospective multicenter study used data from the CCC-ACS and THMDP cohorts. The CCC-ACS project, a collaboration between the Chinese Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, aimed to improve ACS care in China. It included 104,516 ACS patients from 240 hospitals between November 2014 and July 2019. Ethics approval for the use of CCC-ACS data in present study was granted by Beijing Anzhen Hospital’s Institutional Review Board, with the requirement for informed consent waived. The design of the present study has been published elsewhere,22 and CCC-ACS project has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT02306616). Patients were excluded from the CCC-ACS project if they were suspected of ACS on admission, were not treated with PCI, were treated with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and had missing FBG and HbA1c values on admission.

The THMDP is an electronic health record-based healthcare platform covering hospitalization data from all secondary and tertiary hospitals in Tianjin, north China. A detailed description of the THMDP has been published elsewhere.23 To ensure comparability between the 2 databases in the present study, we identified acute myocardial infarction-related hospitalizations using ICD-10 codes I21 and I22, from January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2022. Each patient had a unique encrypted ID for secure visit linkage. Notably, there is no overlap in hospitals between the CCC-ACS project and the THMDP. The use of THMDP data in the present study was approved by the Tianjin Municipal Health Commission and Tianjin Medical University General Hospital Ethics Committee (IRB2024-YX-131-01), with the requirement for informed consent waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Definitions of Exposures and Covariables

SHR was calculated from admission FBG (mg/dL) and HbA1c (%) as follows:3

SHR = FBG / (28.7 × HbA1c − 46.7)

The detection time of FBG in the CCC-ACS cohort and THMDP cohort was restricted to within 48 h after admission to hospital. Glycemic status was categorized as normal glucose regulation (NGR), pre-diabetes mellitus (Pre-DM), and DM. Considering FBG may be influenced by SIH, we chose HbA1c, a medical history of DM, and previous use of hypoglycemic medications to categorize different glycemic status. DM was defined as patients with a medical history of DM, previous use of hypoglycemic medications, or HbA1c ≥6.5% on admission. Pre-DM was defined as those with 5.7%≤HbA1c<6.5% and without DM. NGR was defined as patients with HbA1c <5.7% and without Pre-DM or DM.24 SIH was defined as FBG >125 mg/dL and without DM.1 Glycemic control in DM was defined as HbA1c <7.0%.25

In the present study, the following variables in CCC-ACS cohort were considered as covariates for adjustment: (1) demographic characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI; n=21,101 patients after excluding those with missing data), smoking status, and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or not; (2) medical history, including acute myocardial infarction, PCI, CABG, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, dyslipidemia, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; (3) laboratory tests, including initial estimated glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin, FBG, HbA1c, SHR, and peak creatine kinase-myocardial band (CK-MB), glycemic status, and glycemic control; (4) vital signs on admission, such as heart rate, Killip Class IV, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure, as well as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; n=28,640 patients after excluding those with missing data); (5) prehospital medications, including aspirin or a P2Y12

receptor inhibitor, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEi/ARB), β-blockers, statins, oral anticoagulants, guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), and hypoglycemic agents; and (6) treatment strategies during hospitalization, including administration of aspirin, a P2Y12

receptor inhibitor, ACEi/ARB, β-blockers, statins, unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, oral anticoagulants, intra-aortic balloon pump, and GDMT. GDMT was defined as the administration of aspirin, P2Y12

receptor inhibitors, ACEi/ARB, β-blockers, and statin within 24 h after admission.26–28 The Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network (ACTION) score was calculated according to a previous report.21 Based on Chinese adult weight criteria, BMI was classified into 3 groups: underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 18.5–23.9 kg/m2), overweight and obesity (BMI ≥24 kg/m2).29 In the THMDP cohort, data on BMI, LVEF, and the use of intra-aortic balloon pumping were missing. Apart from these variables, all other variables were consistent with those in the CCC-ACS cohort, based on prior medical history and data from the index hospitalization. High-intensity antithrombotic therapy was defined based on previous literature as treatment with platelet inhibitors and/or anticoagulants.30 Because nearly all ACS patients who underwent PCI in both cohorts received such therapy, we considered most ACS patients in the present study to have received high-intensity antithrombotic treatment.

Definition of Outcomes

The primary outcome in this study was major bleeding, which was defined from previous CCC-ACS studies as: (1) Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3b–3c and 5, including a decrease in hemoglobin ≥5 g/dL, cardiac tamponade, intracranial or fatal bleeding, or the need for surgery or vasoactive agents; (2) Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major bleeding, defined as intracranial or fatal bleeding or a decrease in hemoglobin ≥5 g/dL; and (3) PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO), including fatal or intracranial bleeding, severe surgical bleeding, shock requiring vasopressors or surgery, a decrease in hemoglobin ≥5 g/dL, or transfusion of >4 U of blood.10,17 The secondary outcome was in-hospital death.

Considering the challenges in defining bleeding events in ACS patients as seen in clinical trials or registry studies,31 in the THMDP cohort, an electronic health record-based real-world health data platform, we defined major bleeding as a decrease in hemoglobin ≥5 g/dL, with or without overt bleeding, as proposed recently.32 Consistent with the CCC-ACS cohort, the secondary study outcome in the THMDP cohort was in-hospital death.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean±SD or as the median with interquartile range; categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Rank-sum, t-tests, and Chi-squared tests were used to compare groups, as appropriate. The dose-response relationship between SHR and outcomes was assessed using logistic regression with restricted cubic splines (RCS). SHR was dichotomized using the Quartile 4 (Q4) cut-off, and its association with outcomes was evaluated.

In sensitivity analyses, we excluded patients with hypotension, those who died within 24 or 48 h of hospitalization, or those who had undergone PCI/CABG previously. The predictive performance of the ACTION score combined with FBG compared with that of the ACTION score combined with SHR was compared in 23,658 CCC-ACS patients using the area under the curve (AUC). Because >20% of the THMDP cohort had missing admission heart rate data, the predictive ability of SHR and FBG was assessed only in the CCC-ACS cohort.

Subgroup analysis examined associations between SHR and major bleeding across age, sex, STEMI, early β-blocker, ACEi/ARB, GDMT therapy, and history of GDMT therapy. Interaction effects were assessed using multivariable fractional polynomial interactions. Covariables were all included in adjusted models. The THMDP cohort was used to externally validate the main results from the CCC-ACS cohort. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), with two-tailed P<0.05 indicating significance.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

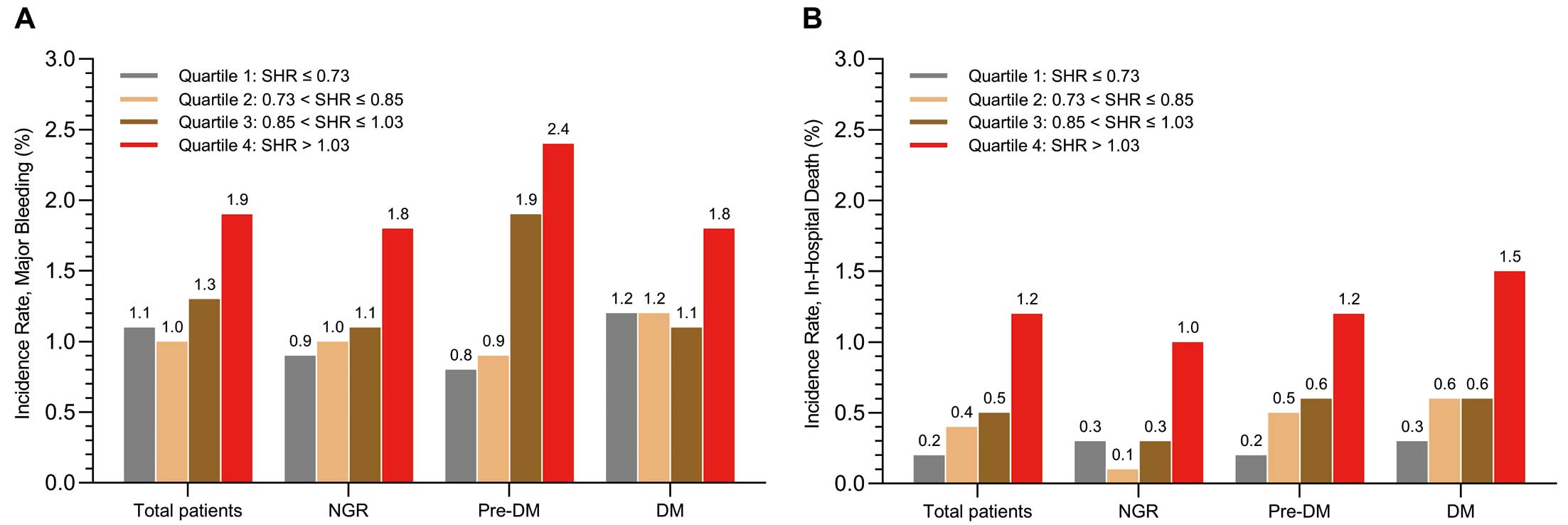

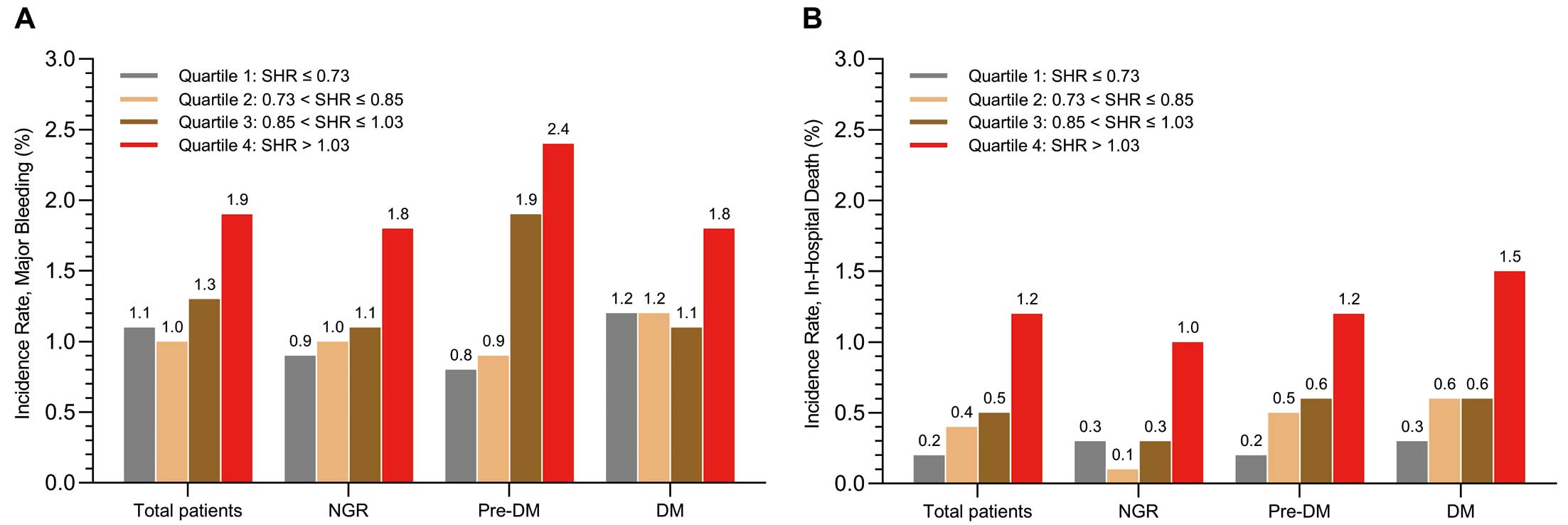

As shown in Figure 1, we analyzed 33,265 ACS patients treated with PCI in the CCC-ACS cohort. Of these patients, 437 (1.31%) experienced major bleeding and 193 (0.58%) died during hospitalization. Patients were divided into 4 groups based on SHR quartiles: Q1, SHR ≤0.73; Q2, 0.73<SHR≤0.85; Q3, 0.85<SHR≤1.03, and Q4, SHR >1.03. Compared with Q1, Q4 had more STEMI patients, higher FBG levels, lower HbA1c, higher peak CK-MB levels, and fewer patients receiving GDMT (Table 1). Patients who experienced major bleeding were characterized by older age, a higher incidence of STEMI, higher peak CK-MB, higher FBG and SHR levels, and a lower rate of GDMT use (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in the CCC-ACS Cohort Stratified by Admission Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio Quartiles

| |

Q1

(n=8,553) |

Q2

(n=8,280) |

Q3

(n=8,324) |

Q4

(n=8,108) |

P value |

| Demographics |

| Age (years) |

62.3±11.8 |

61.5±11.9 |

61.0±11.9 |

61.8±12.1 |

<0.001 |

| Male sex |

6,710 (78.5) |

6,576 (79.4) |

6,557 (78.8) |

6,236 (76.9) |

<0.001 |

| BMI |

| <18.5 kg/m2 |

152 (2.7) |

123 (2.4) |

109 (2.1) |

123 (2.4) |

0.097 |

| 18.5–24 kg/m2 |

2,297 (41.4) |

2,197 (42.3) |

2,122 (40.4) |

2,149 (42.1) |

|

| ≥24 kg/m2 |

3,095 (55.8) |

2,880 (55.4) |

3,025 (57.6) |

2,829 (55.5) |

|

| STEMI |

5,084 (59.4) |

5,078 (61.3) |

5,533 (66.5) |

5,850 (72.2) |

<0.001 |

| Smoking |

4,153 (48.6) |

4,163 (50.3) |

4,075 (49.0) |

3,881 (47.9) |

0.017 |

| Medical history |

| AMI |

675 (7.9) |

581 (7.0) |

555 (6.7) |

555 (6.7) |

<0.001 |

| PCI |

799 (9.3) |

677 (8.2) |

623 (7.5) |

517 (6.4) |

<0.001 |

| CABG |

38 (0.4) |

33 (0.4) |

32 (0.4) |

16 (0.2) |

0.042 |

| Dyslipidemia |

415 (4.9) |

393 (4.7) |

393 (4.7) |

393 (4.7) |

<0.001 |

| Hypertension |

4,629 (54.1) |

4,359 (52.6) |

4,442 (53.4) |

4,326 (53.4) |

0.30 |

| Atrial fibrillation |

173 (2.0) |

111 (1.3) |

134 (1.6) |

120 (1.5) |

0.003 |

| Heart failure |

101 (1.2) |

76 (0.9) |

78 (0.9) |

80 (1.0) |

0.30 |

| Ischemic stroke |

636 (7.4) |

548 (6.6) |

556 (6.7) |

591 (7.3) |

0.082 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke |

48 (0.6) |

46 (0.6) |

47 (0.6) |

53 (0.7) |

0.82 |

| COPD |

142 (1.7) |

95 (1.1) |

67 (0.8) |

89 (1.1) |

<0.001 |

| Laboratory tests on admission |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

88.9 [70.8–100.2] |

90.8 [74.5–101.3] |

91.3 [74.8–101.8] |

89.1 [70.8–101.0] |

<0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

13.8 [12.5–15.0] |

14.0 [12.8–15.1] |

14.1 [12.8–15.2] |

13.9 [12.6–15.2] |

<0.001 |

| Peak CK-MB (U/L) |

13.2 [3.6–49.2] |

16.7 [4.0–58.9] |

23.6 [5.8–71.4] |

27.7 [6.5–81.4] |

<0.001 |

| FBG (mg/dL) |

88.2 [79.2–111.6] |

99.0 [90.0–115.2] |

113.4 [102.6–136.8] |

163.8 [133.2–216.0] |

<0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) |

6.5 [5.9–8.3] |

6.0 [5.6–6.7] |

5.9 [5.5–6.7] |

6.0 [5.5–7.1] |

<0.001 |

| Glycemic status |

| NGR |

1,513 (17.7) |

2,886 (34.9) |

3,460 (41.6) |

3,014 (37.2) |

<0.001 |

| Pre-DM |

2,514 (29.4) |

2,609 (31.5) |

1,935 (23.2) |

1,605 (19.8) |

|

| DM |

4,526 (52.9) |

2,785 (33.6) |

2,929 (35.2) |

3,489 (43.0) |

|

| Glycemic control status |

| NGR |

1,513 (17.7) |

2,886 (34.9) |

3,460 (41.6) |

3,014 (37.2) |

<0.001 |

| Pre-DM |

2,514 (29.4) |

2,609 (31.5) |

1,935 (23.2) |

1,605 (19.8) |

|

| Controlled glycemia |

1,043 (12.2) |

1,020 (12.3) |

1,104 (13.3) |

1,271 (15.7) |

|

| Uncontrolled glycemia |

3,483 (40.7) |

1,765 (21.3) |

1,825 (21.9) |

2,218 (27.3) |

|

| Vital signs and LVEF |

| Heart rate (beats/min) |

76.0 [67.0–85.0] |

75.0 [67.0–85.0] |

75.0 [67.0–85.0] |

78.0 [68.0–89.0] |

<0.001 |

| Killip Class IV |

258 (3.0) |

200 (2.4) |

230 (2.8) |

358 (4.4) |

<0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) |

129.0 [115.0–145.0] |

130.0 [115.0–145.0] |

130.0 [115.0–145.5] |

129.0 [113.0–145.0] |

0.038 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

77.0 [69.0–86.0] |

78.0 [70.0–87.0] |

78.0 [70.0–88.0] |

78.0 [69.0–88.0] |

<0.001 |

| LVEF (%) |

58.0 [50.0–63.0] |

58.0 [51.0–63.0] |

57.0 [50.0–62.0] |

56.0 [48.0–61.0] |

<0.001 |

| Prehospital medications |

| Aspirin |

2,180 (25.5) |

1,804 (21.8) |

1,671 (20.1) |

1,563 (19.3) |

<0.001 |

| P2Y12 receptor inhibitor |

1,609 (18.8) |

1,337 (16.1) |

1,260 (15.1) |

1,205 (14.9) |

<0.001 |

| β-blockers |

953 (11.1) |

795 (9.6) |

772 (9.3) |

678 (8.4) |

<0.001 |

| ACEi/ARB |

995 (11.6) |

877 (10.6) |

872 (10.5) |

729 (9.0) |

<0.001 |

| Statin |

1,706 (19.9) |

1,435 (17.3) |

1,265 (15.2) |

1,204 (14.8) |

<0.001 |

| Oral anticoagulants |

33 (0.4) |

18 (0.2) |

18 (0.2) |

17 (0.2) |

0.064 |

| GDMT |

259 (3.0) |

213 (2.6) |

196 (2.4) |

171 (2.1) |

0.001 |

| Hypoglycemic agent |

2,461 (28.8) |

1,427 (17.2) |

1,678 (20.2) |

2,126 (26.2) |

<0.001 |

| In-hospital treatment in the first 24 h |

| Aspirin |

7,956 (93.0) |

7,774 (93.8) |

7,852 (94.3) |

7,681 (94.7) |

<0.001 |

| P2Y12 receptor inhibitor |

8,032 (93.9) |

7,849 (94.8) |

7,966 (95.7) |

7,791 (96.1) |

<0.001 |

| β-blockers |

5,295 (61.9) |

5,022 (60.7) |

5,041 (60.6) |

4,711 (58.1) |

<0.001 |

| ACEi/ARB |

4,519 (52.8) |

4,369 (52.8) |

4,310 (51.8) |

3,964 (48.9) |

<0.001 |

| Statin |

8,208 (96.0) |

7,923 (95.7) |

7,958 (95.6) |

7,720 (95.2) |

0.13 |

| Unfractionated heparin |

304 (3.6) |

319 (3.9) |

365 (4.4) |

330 (4.1) |

0.043 |

| LMWH |

5,856 (68.5) |

5,707 (68.9) |

5,775 (69.4) |

5,401 (66.6) |

<0.001 |

| Oral anticoagulants |

59 (0.7) |

42 (0.5) |

40 (0.5) |

48 (0.6) |

0.26 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump |

73 (0.9) |

53 (0.6) |

69 (0.8) |

73 (0.9) |

0.26 |

| GDMT |

3,213 (37.6) |

3,135 (37.9) |

3,135 (37.7) |

2,848 (35.1) |

<0.001 |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the mean±SD, median [interquartile range], or n (%). Note: body mass index (BMI) values were available for 21,101 patients, and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured within 24 h of admission in 28,640 patients. ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCC-ACS, Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-Acute Coronary Syndrome; CK-MB, creatine kinase-myocardial band; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FBG, fasting blood glucose; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; NGR, normal glucose regulation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Pre-DM, pre-diabetes mellitus; Q1–Q4, quartiles 1–4; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SHR, stress hyperglycemia ratio; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

In the THMDP cohort, we included 23,423 patients with acute myocardial infarction who were treated with PCI. Of these patients, 392 (1.67%) experienced major bleeding and 114 (0.49%) died during hospitalization. Patients in the THMDP cohort were also divided into SHR quartiles: Q1, SHR ≤0.79; Q2, 0.79<SHR≤0.93; Q3, 0.93<SHR≤1.13; and Q4, SHR >1.13. Similar to the CCC-ACS cohort, patients in the THMDP cohort in Q4 had higher levels of FBG, HbA1c and peak CK-MB, and a higher incidence of STEMI than those in Q1 (Supplementary Table 2). Patients in the THMDP cohort who experienced major bleeding were older and had higher FBG levels (Supplementary Table 3).

SHR and Study Outcomes Across Glycemic Status

Figure 2 shows the incidence of major bleeding and in-hospital death across SHR quartiles in the CCC-ACS cohort, stratified by glycemic status. A dose-dependent trend was observed for both outcomes, with the highest incidence of major bleeding and in-hospital death occurring in SHR Q4 (>1.03). In logistic models, SHR Q4 was linked to the highest risks of major bleeding (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.61; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.23–2.10) and in-hospital death (aOR 4.03; 95% CI 2.50–6.50) compared with Q1 (Supplementary Table 4). The RCS models revealed a “J-shaped” relationship between SHR and both major bleeding and in-hospital death (Figure 3), with a continuous upward trend for major bleeding at SHR values exceedingly approximate 1.0 in the adjusted model. Similar patterns were observed across different glycemic status (Supplementary Figures 1,2).

We therefore standardized the SHR threshold at >1.0 (high SHR), based on the lower boundary of Q4 (1.03) and RCS analyses, rounded to 1.0, for subsequent analyses. As indicated in Table 2, high (>1.0) SHR increased the risk of major bleeding by 51%, 56%, and 37% in the total cohort, NGR, and DM groups, respectively. It is worth highlighting that in patients with Pre-DM, high SHR (>1.0) was associated with the higher risk of major bleeding by 98% (aOR 1.98; 95% CI 1.34–2.92), resulting in nearly double the absolute risk compared with the NGR and DM groups. Notably, similar magnitudes of risk of death were observed across the total cohort and different glycemic status, with aOR ranging from 2.46 to 2.55. When DM was further classified into controlled and uncontrolled glycemia, the borderline significance of the association between high SHR and major bleeding was no longer observed in either group. However, the consistent and similar magnitude of association with death remained regardless of glycemic control status (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2.

Associations of Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio With Study Outcomes Across Different Glycemic Status in the CCC-ACS Cohort

| |

High SHR (>1.0) vs. low SHR |

| Crude model |

Adjusted model |

| OR |

P value |

Absolute risk

difference (%) |

P value |

OR |

P value |

Absolute risk

difference (%) |

P value |

| Major bleeding |

| All patients |

1.71 (1.41–2.07) |

<0.001 |

0.76 (0.46–1.06) |

<0.001 |

1.51 (1.24–1.83) |

<0.001 |

0.56 (0.27–0.85) |

<0.001 |

| NGR |

1.74 (1.24–2.45) |

0.001 |

0.72 (0.24–1.21) |

0.003 |

1.56 (1.10–2.22) |

0.012 |

0.56 (0.10–1.03) |

0.012 |

| Pre-DM |

2.16 (1.48–3.14) |

<0.001 |

1.24 (0.52–1.96) |

<0.001 |

1.98 (1.34–2.92) |

0.001 |

1.06 (0.35–1.76) |

0.001 |

| DM |

1.50 (1.11–2.03) |

0.008 |

0.58 (0.12–1.04) |

0.014 |

1.37 (1.01–1.86) |

0.044 |

0.44 (0.01–0.89) |

0.048 |

| In-hospital death |

| All patients |

3.25 (2.45–4.33) |

<0.001 |

0.79 (0.56–1.02) |

<0.001 |

2.46 (1.84–3.30) |

<0.001 |

0.55 (0.35–0.75) |

<0.001 |

| NGR |

3.30 (1.86–5.85) |

<0.001 |

0.60 (0.27–0.92) |

<0.001 |

2.52 (1.30–4.72) |

0.005 |

0.41 (0.11–0.70) |

0.008 |

| Pre-DM |

3.39 (1.91–6.01) |

<0.001 |

0.84 (0.33–1.35) |

0.001 |

2.55 (1.39–4.69) |

0.003 |

0.59 (0.13–1.05) |

0.003 |

| DM |

3.29 (2.19–4.94) |

<0.001 |

0.95 (0.57–1.34) |

<0.001 |

2.50 (1.65–3.80) |

<0.001 |

0.67 (0.33–1.01) |

<0.001 |

Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals. Covariates are described in the Statistical Analysis section in the text. OR, odds ratio. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

In the THMDP cohort, high SHR was most strongly associated with major bleeding in patients with Pre-DM (aOR 2.30; 95% CI 1.40–3.77), followed by patients with DM (aOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.38–2.35), with no association in patients with NGR (aOR 1.09; 95% CI 0.59–1.99; Supplementary Table 6). The difference in major bleeding risk was statistically significant (Pinteraction=0.021). For in-hospital death, high SHR was linked to risk in patients with Pre-DM and DM. Although the association with mortality in patients with NGR was not statistically significant, a trend for increased risk was observed. As for glycemic control status (Supplementary Table 7), high SHR was associated with a higher risk of major bleeding in patients with DM and uncontrolled glycemia (aOR 2.06; 95% CI 1.47–2.90; Pinteraction=0.035). Moreover, high SHR was associated with in-hospital death in patients with DM and controlled glycemia (aOR 8.76; 95% CI 2.54–30.24) compared with those with uncontrolled glycemia.

Sensitivity analysis confirmed that high SHR remained an independent risk factor for major bleeding in both cohorts (Supplementary Figure 3). In addition, in the CCC-ACS cohort, we found SHR was associated with the highest risk of major bleeding in patients who were underweight (aOR 4.20; 95% CI 1.02–36.62; Supplementary Table 8). Early GDMT administration was associated with a lower major bleeding risk, regardless of LVEF status (≥50% vs. <50%). When stratified by diagnostic status, the CCC-ACS and THMDP cohorts contained 4,328 and 1,270 patients newly diagnosed with DM, respectively. Patients with newly diagnosed DM had the second-highest bleeding risk in the CCC-ACS cohort (aOR 1.77; 95% CI 1.06–3.17) and the highest in the THMDP cohort (aOR 3.11; 95% CI 1.02–10.98; Supplementary Table 9).

Predictive Performance for Major Bleeding

We incorporated FBG and SHR into the ACTION score to assess their predictive value for major bleeding in the CCC-ACS cohort. When FBG and SHR were treated as continuous variables, the ACTION score combined with SHR demonstrated superior predictive performance, significantly improving the AUC (0.679 [95% CI 0.644–0.714] vs. 0.645 [95% CI 0.611–0.679]; P<0.001) compared with the ACTION score alone, and also outperforming the ACTION score combined with FBG (0.679 [95% CI 0.644–0.714] vs. 0.652 [95% CI 0.618–0.686]; P<0.001). Similar results were observed when FBG and SHR were treated as categorical variables (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictive Performance for Major Bleeding

| Models |

AUC

(95% CI) |

P value |

| FBG and SHR as continuous variables |

| Model 1: ACTION score |

0.645 (0.611–0.679) |

Ref. |

| Model 2: Model 1+FBG |

0.652 (0.618–0.686) |

0.026 |

| Model 3: Model 1+SHR |

0.679 (0.644–0.714) |

<0.001 |

| FBG and SHR as categorical variables |

| Model 1: ACTION score |

0.645 (0.611–0.679) |

Ref. |

| Model 4: Model 1+FBG |

0.650 (0.616–0.684) |

0.067 |

| Model 5: Model 1+SHR |

0.678 (0.642–0.713) |

<0.001 |

| FBG and SHR as continuous variables |

| Model 2: Model 1+FBG |

0.652 (0.618–0.686) |

Ref. |

| Model 3: Model 1+SHR |

0.679 (0.644–0.714) |

<0.001 |

| FBG and SHR as categorical variables |

| Model 4: Model 1+FBG |

0.650 (0.616–0.684) |

Ref. |

| Model 5: Model 1+SHR |

0.678 (0.642–0.713) |

<0.001 |

FBG was transformed into categorical variable using a cut-off value of 125 mg/dL. The SHR was transformed into a categorical variable using a cut-off value of 1.0. ACTION, Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network; AUC, area under curve; CI, confidence interval. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Subgroup Analysis

In the CCC-ACS and THMDP cohorts, we assessed the relationship between SHR and major bleeding across subgroups according to age, sex, STEMI or not, early administration of β-blockers, ACEi/ARB, GDMT, and history of GDMT therapy. Although no significant interactions were observed, high SHR-related bleeding risk was attenuated in patients who received early administration of β-blockers, ACEi/ARB, and GDMT (Supplementary Figure 4).

Modification of Bleeding Risk With GDMT Across the Full Spectrum of SHR

We next evaluated the impact of early GDMT on bleeding risk across the full spectrum of SHR by using multivariable fractional polynomial interactions models (Supplementary Figure 5). Although no significant interactions were observed in the CCC-ACS cohort, the early use of GDMT was consistently associated with a reduction in major bleeding, with a more pronounced effect seen in patients with higher SHR in the CCC-ACS cohort. In addition, the early use of β-blockers and ACEi/ARB was linked to a reduction in major bleeding risk as SHR increased in the CCC-ACS cohort.

Discussion

This study found that high SHR increased the risk of major bleeding during hospitalization in ACS patients on high-intensity antithrombotic therapy, especially in those with Pre-DM. Including SHR improved the predictive accuracy of the ACTION score, whereas early GDMT therapy reduced the risk of major bleeding. These findings suggest SHR as a modifiable predictor of post-PCI bleeding, particularly in the setting of Pre-DM, warranting further trials on SHR-targeted strategies to reduce bleeding risk.

Although FBG is associated with poor outcomes in ACS patients, it fails to accurately capture SIH due to chronic glucose fluctuations. SHR, a cost-effective biomarker, overcomes this limitation by providing a more reliable measure of the acute glycemic response.3 Previous studies have shown that high SHR is associated with increased mortality and ischemic events in both short- and long-term follow-up.4–7 Yang et al. demonstrated a J-shaped relationship between SHR and in-hospital death and non-fatal myocardial infarction in 5,562 ACS patients after PCI,5 whereas Liu et al. showed that SHR increased long-term mortality risk, particularly in patients without DM.20 A small cohort study explored SHR and major bleeding but lacked systematic analysis,33 emphasizing the need for larger cohort studies. The present study found that high SHR was associated with an increased risk of major bleeding and in-hospital death, primarily driven by patients with Pre-DM. Several pathophysiological mechanisms may explain this. Mild to moderate SHR during acute ACS exerts a protective role by enhancing cell survival and reducing apoptosis, thus decreasing infarct size and improving systolic function.20,34 Conversely, a higher SHR is associated with increased levels of inflammation and inflammatory markers (e.g., superoxide, plasma kallikrein, tumor necrosis factor-α), which may impair endothelial function and potentially elevate the risk of in-hospital death and major bleeding.14–16,34,35

As inflammatory markers progressively increase from NGR to Pre-DM and DM,36 patients with DM typically manage their blood glucose with hypoglycemic medications, whereas patients with Pre-DM often do not. This lack of medication in patients with Pre-DM, combined with their more fragile glucose metabolism, leads to greater fluctuations in glucose homeostasis during acute stress. These disruptions can result in more severe stress hyperglycemia, which may exacerbate systemic inflammation. Unlike DM, where compensatory mechanisms from chronic hyperglycemia and medication use offer some protection,37,38 patients with Pre-DM are more vulnerable to stress-induced glycemic disturbances and heightened inflammatory responses. Moreover, we found that newly diagnosed DM patients had a bleeding risk similar to those with Pre-DM, possibly due to shared mechanisms, such as no prior hypoglycemic therapy.39 Notably, we demonstrated that high SHR can also identify high-risk populations within DM patients. For those with well-controlled blood glucose, their relatively lower HbA1c levels mean that even a slight increase in glucose in response to stress leads to a more pronounced rise in SHR. This increase is linked to elevated short-term risks of bleeding and mortality. Therefore, this unique metabolic instability, combined with amplified inflammatory responses, may serve as a biomarker to identify individuals with Pre-DM and well-controlled DM at heightened risk of major bleeding and death.15,16 We also observed that high SHR was linked to the highest bleeding risk in underweight patients, likely due to their poor baseline profile.40

Major bleeding increased the risk of in-hospital death in ACS patients after PCI.41,42 Previous studies suggest that ACEi/ARB are associated with a reduced risk of major bleeding in patients with left ventricular assist devices, which may result from the inhibition of angiotensin II receptor activation, suppressing the transforming growth factor-β and angiopoietin-2 pathways.43,44 In the context of SIH, inflammatory responses are further amplified. ACEi/ARB may further reduce the risk of major bleeding associated with SIH through this mechanism. Moreover, in a previous study we found that early β-blocker administration reduced major bleeding risk,17 which aligns with the results of the present study, and may be attributed, in part, to the effects of β-blockers in regulating vasodilation. Early β-blocker administration may mitigate the severity of stress responses caused by SIH and reduce peripheral vasoconstriction, ultimately lowering the risk of major bleeding. In the present study, we found that GDMT primarily reduced the risk of major bleeding in SIH through the effects of the early administration of β-blockers and ACEi/ARB. Recent studies have demonstrated that the early use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors can improve cardiometabolic outcomes, lower the risk of heart failure hospitalization, and maintain a favorable safety profile.45 To reduce the risk of bleeding and mortality, future research should explore the efficacy of incorporating this class of medications as SHR-targeted therapy in ACS patients following PCI, particularly for patients with Pre-DM or those with controlled glycemia but high SHR. In addition, efforts to incorporate SHR into the ACTION score to enhance its predictive performance for major bleeding are also warranted.

Strengths and Limitations

This nationwide registry represents the first exploration of the relationship between SHR and major bleeding in ACS patients after PCI across different glycemic status. Further, we used the THMDP cohort to perform an external validation of the results from the CCC-ACS cohort and demonstrate that a cut-off value of 1.0 for SHR is appropriate. In addition, in the present study, FBG was used to calculate SHR, rendering the SHR value relatively stable and minimizing the likelihood of errors in SHR due to random blood glucose. Moreover, in the THMDP cohort, we restricted the detection time of FBG to within 48 h after admission to hospital, which may offer a reference for subsequent related studies.

Despite these strengths, the study has several limitations. First, the study population was predominantly Chinese, necessitating validation in diverse ethnic groups. Second, further basic research is needed to validate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying SIH and major bleeding. Third, residual measured and unmeasured confounding may have affected some of these findings. Fourth, the use of mechanical circulatory support devices may increase major bleeding risk. However, due to low utilization rate of these devices in China, data on them were lacking. Further studies are needed to assess their impact. Finally, as an observational study, causality between SHR and major bleeding or death cannot be established.

Conclusions

In 2 large cohorts, high SHR (>1.0) was identified as an independent risk factor for major bleeding in ACS patients following PCI on high-intensity antithrombotic therapy, with this risk being especially pronounced in patients with Pre-DM. Although the early use of GDMT potentially mitigated the bleeding risk associated with high SHR, further clinical trials are needed to explore SHR-targeted therapies in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the hospitals participating in the CCC-ACS project for their contribution to this work.

Sources of Funding

The CCC-ACS project is a program of the American Heart Association (AHA) and the Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC). The AHA has been funded by Pfizer and AstraZeneca for a quality improvement initiative through an independent grant for learning and change. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270349 and 72274133) and Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (Grant no. TJYXZDXK-069C).

Disclosures

G.C.F. reports consulting for Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

C.Z., J.L., and W.L. contributed to the study design, data analysis, and writing the initial version of the manuscript. H.L., P.S., Y.F., J.Y., H.S., Y. Li, R.S.-Y.F., C.S., and G.C.F. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. Q.Y., Y. Liu, and X.Z. serve as corresponding authors for the manuscript, and contributed to the study design, study supervision, and revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

IRB Information

The Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, approved the use of the CCC-ACS cohort, with the requirement for informed consent waived due to the large-scale nature of the study. The use of data for the THMDP cohort was approved by the Tianjin Municipal Health Commission and the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, with the requirement for informed consent waived due to the retrospective design of the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Data Availability

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.

Supplementary Files

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-25-0017

References

- 1.

Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 2009; 373: 1798–1807.

- 2.

Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Gerstein HC. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: A systematic overview. Lancet 2000; 355: 773–778.

- 3.

Roberts GW, Quinn SJ, Valentine N, Alhawassi T, O’Dea H, Stranks SN, et al. Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: Introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100: 4490–4497.

- 4.

Li K, Yang X, Li Y, Xu G, Ma Y. Relationship between stress hyperglycaemic ratio and incidence of in-hospital cardiac arrest in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2024; 23: 59.

- 5.

Yang J, Zheng Y, Li C, Gao J, Meng X, Zhang K, et al. The impact of the stress hyperglycemia ratio on short-term and long-term poor prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Insight from a large cohort study in Asia. Diabetes Care 2022; 45: 947–956.

- 6.

Cui K, Fu R, Yang J, Xu H, Yin D, Song W, et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: A prospective, nationwide, and multicentre registry. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2022; 38: e3562.

- 7.

Sia CH, Chan MH, Zheng H, Ko J, Ho AF, Chong J, et al. Optimal glucose, HbA1c, glucose-HbA1c ratio and stress-hyperglycaemia ratio cut-off values for predicting 1-year mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic acute myocardial infarction patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021; 20: 211.

- 8.

Marenzi G, Cosentino N, Milazzo V, De Metrio M, Cecere M, Mosca S, et al. Prognostic value of the acute-to-chronic glycemic ratio at admission in acute myocardial infarction: A prospective study. Diabetes Care 2018; 41: 847–853.

- 9.

Okita S, Saito Y, Yaginuma H, Asada K, Goto H, Hashimoto O, et al. Impact of the stress hyperglycemia ratio on heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 2025; 89: 340–346.

- 10.

Yang Q, Sun D, Pei C, Zeng Y, Wang Z, Li Z, et al. LDL cholesterol levels and in-hospital bleeding in patients on high-intensity antithrombotic therapy: Findings from the CCC-ACS project. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 3175–3186.

- 11.

Kwon O, Ahn JH, Koh JS, Park Y, Hwang SJ, Tantry US, et al. Platelet-fibrin clot strength and platelet reactivity predicting cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J 2024; 45: 2217–2231.

- 12.

Hong SJ, Kim BK. Potent P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy for acute coronary syndrome. Circ J 2025; 89: 272–280.

- 13.

Nouh CD, Ray B, Xu C, Zheng B, Danala G, Koriesh A, et al. Quantitative analysis of stress-induced hyperglycemia and intracranial blood volumes for predicting mortality after intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res 2022; 13: 595–603.

- 14.

Chu H, Huang C, Tang Y, Dong Q, Guo Q. The stress hyperglycemia ratio predicts early hematoma expansion and poor outcomes in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2022; 15: 17562864211070681.

- 15.

Won SJ, Tang XN, Suh SW, Yenari MA, Swanson RA. Hyperglycemia promotes tissue plasminogen activator-induced hemorrhage by Increasing superoxide production. Ann Neurol 2011; 70: 583–590.

- 16.

Liu J, Gao BB, Clermont AC, Blair P, Chilcote TJ, Sinha S, et al. Hyperglycemia-induced cerebral hematoma expansion is mediated by plasma kallikrein. Nat Med 2011; 17: 206–210.

- 17.

Xu S, Li Z, Yang T, Li L, Song X, Hao Y, et al. Association between early oral β-blocker therapy and risk for in-hospital major bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome: Findings from CCC-ACS project. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2022, doi:10.1093/ehjqcco/qcac036.

- 18.

Simonsson M, Wallentin L, Alfredsson J, Erlinge D, Hellström Ängerud K, Hofmann R, et al. Temporal trends in bleeding events in acute myocardial infarction: Insights from the SWEDEHEART registry. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 833–843.

- 19.

Arai R, Okumura Y, Murata N, Fukamachi D, Honda S, Nishihira K, et al. Prevalence and impact of polyvascular disease in patients with acute myocardial infarction in the contemporary era of percutaneous coronary intervention: Insights from the Japan Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (JAMIR). Circ J 2024; 88: 911–920.

- 20.

Liu J, Zhou Y, Huang H, Liu R, Kang Y, Zhu T, et al. Impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality in patients with critical acute myocardial infarction: Insight from American MIMIC-IV and the Chinese CIN-II study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023; 22: 281.

- 21.

Mathews R, Peterson ED, Chen AY, Wang TY, Chin CT, Fonarow GC, et al. In-hospital major bleeding during ST-elevation and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction care: Derivation and validation of a model from the ACTION Registry®-GWTGTM. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107: 1136–1143.

- 22.

Hao Y, Liu J, Liu J, Smith SC Jr, Huo Y, Fonarow GC, et al. Rationale and design of the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China (CCC) project: A national effort to prompt quality enhancement for acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J 2016; 179: 107–115.

- 23.

Liu Y, Li L, Li J, Liu H, Geru A, Wang Y, et al. Development and validation of a predictive model for intracranial haemorrhage in patients on direct oral anticoagulants. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2024; 30: 10760296241271338.

- 24.

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2021. Diabetes Care 2021; 44(Suppl 1): S15–S33.

- 25.

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 6. Glycemic targets: Standards of Care in Diabetes – 2023. Diabetes Care 2023; 46(Suppl 1): S97–S110.

- 26.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119–177.

- 27.

O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 127: e362–e425.

- 28.

Zhang C, Sun P, Li Z, Sun H, Zhao D, Liu Y, et al. The potential role of the triglyceride–glucose index in left ventricular systolic function and in-hospital outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2024; 117: 204–212.

- 29.

Pan XF, Wang L, Pan A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021; 9: 373–392.

- 30.

Halperin JL, Chen H, Olin JW. Antithrombotic therapy to reduce mortality in patients with atherosclerosis: 2 pathways to a single goal. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021; 78: 24–26.

- 31.

Kikkert WJ, Tijssen JGP, Piek JJ, Henriques JPS. Challenges in the adjudication of major bleeding events in acute coronary syndrome: A plea for a standardized approach and guidance to adjudication. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 1104–1112.

- 32.

Leonardi S, Gragnano F, Carrara G, Gargiulo G, Frigoli E, Vranckx P, et al. Prognostic implications of declining hemoglobin content in patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021; 77: 375–388.

- 33.

Chen G, Li M, Wen X, Wang R, Zhou Y, Xue L, et al. Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital outcomes in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021; 8: 698725.

- 34.

Wang M, Su W, Cao N, Chen H, Li H. Prognostic implication of stress hyperglycemia in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2023; 22: 63.

- 35.

Paolisso P, Foà A, Bergamaschi L, Angeli F, Fabrizio M, Donati F, et al. Impact of admission hyperglycemia on short and long-term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction: MINOCA versus MIOCA. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021; 20: 192.

- 36.

Grossmann V, Schmitt VH, Zeller T, Panova-Noeva M, Schulz A, Laubert-Reh D, et al. Profile of the immune and inflammatory response in individuals with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1356–1364.

- 37.

Ingels C, Vanhorebeek I, Van den Berghe G. Glucose homeostasis, nutrition and infections during critical illness. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24: 10–15.

- 38.

Dandona P, Chaudhuri A, Ghanim H, Mohanty P. Insulin as an anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic modulator. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53(Suppl): S14–S20.

- 39.

Bjarnason TA, Hafthorsson SO, Kristinsdottir LB, Oskarsdottir ES, Johnsen A, Andersen K. The prognostic effect of known and newly detected type 2 diabetes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2020; 9: 608–615.

- 40.

Won KB, Shin ES, Kang J, Yang HM, Park KW, Han KR, et al. Body mass index and major adverse events during chronic antiplatelet monotherapy after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents-results from the HOST-EXAM trial. Circ J 2023; 87: 268–276.

- 41.

Lopes RD, Subherwal S, Holmes DN, Thomas L, Wang TY, Rao SV, et al. The association of in-hospital major bleeding with short-, intermediate-, and long-term mortality among older patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2044–2053.

- 42.

Doyle BJ, Rihal CS, Gastineau DA, Holmes DR Jr. Bleeding, blood transfusion, and increased mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: Implications for contemporary practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53: 2019–2027.

- 43.

Converse MP, Sobhanian M, Taber DJ, Houston BA, Meadows HB, Uber WE. Effect of angiotensin II inhibitors on gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with left ventricular assist devices. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 1769–1778.

- 44.

Houston BA, Schneider AL, Vaishnav J, Cromwell DM, Miller PE, Faridi KF, et al. Angiotensin II antagonism is associated with reduced risk for gastrointestinal bleeding caused by arteriovenous malformations in patients with left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36: 380–385.

- 45.

Peikert A, Vaduganathan M. Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibition following acute myocardial infarction: The DAPA-MI and EMPACT-MI trials. JACC Heart Fail 2024; 12: 949–953.