Abstract

Background:

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) in the very elderly is poorly understood. We sought to clarify the characteristics of octogenarians and nonagenarians with TTS.

Methods and Results:

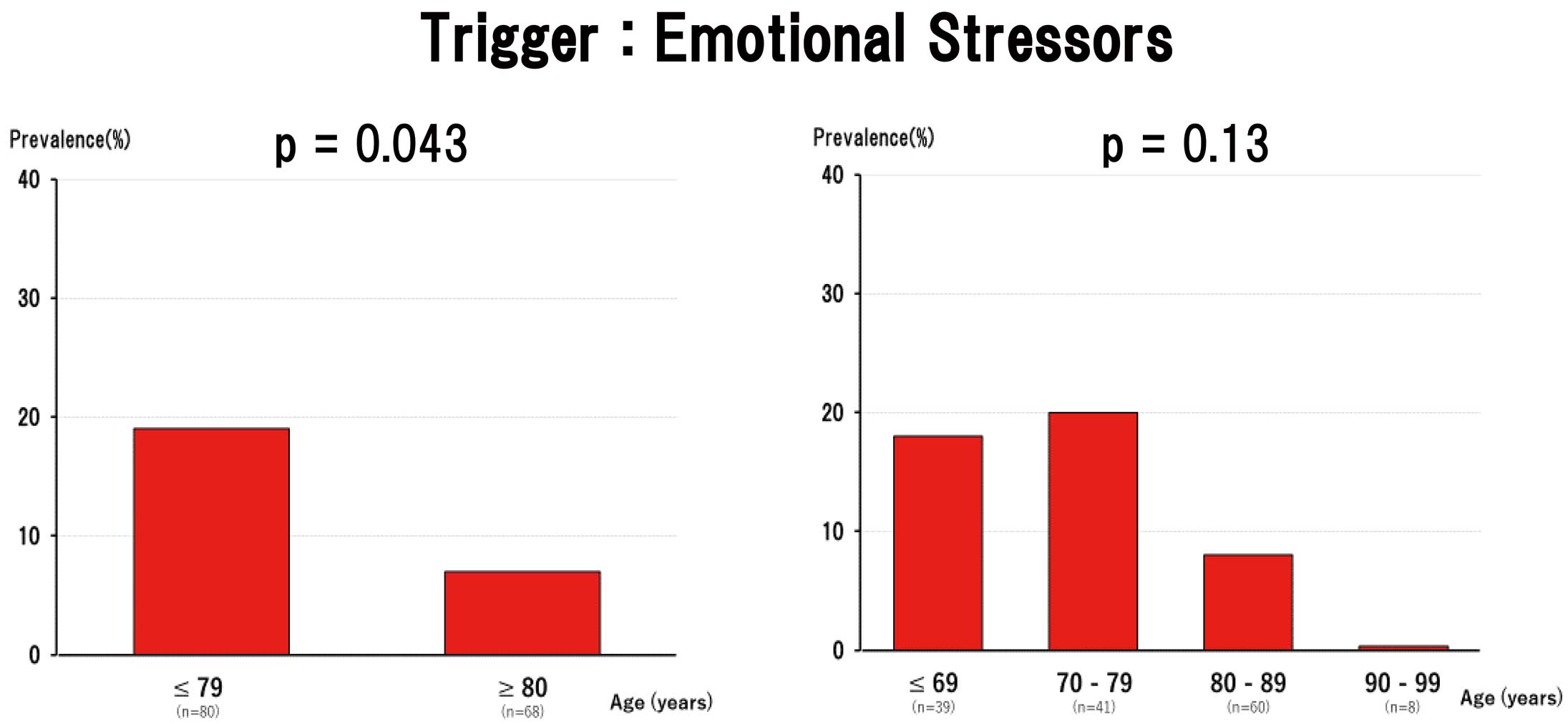

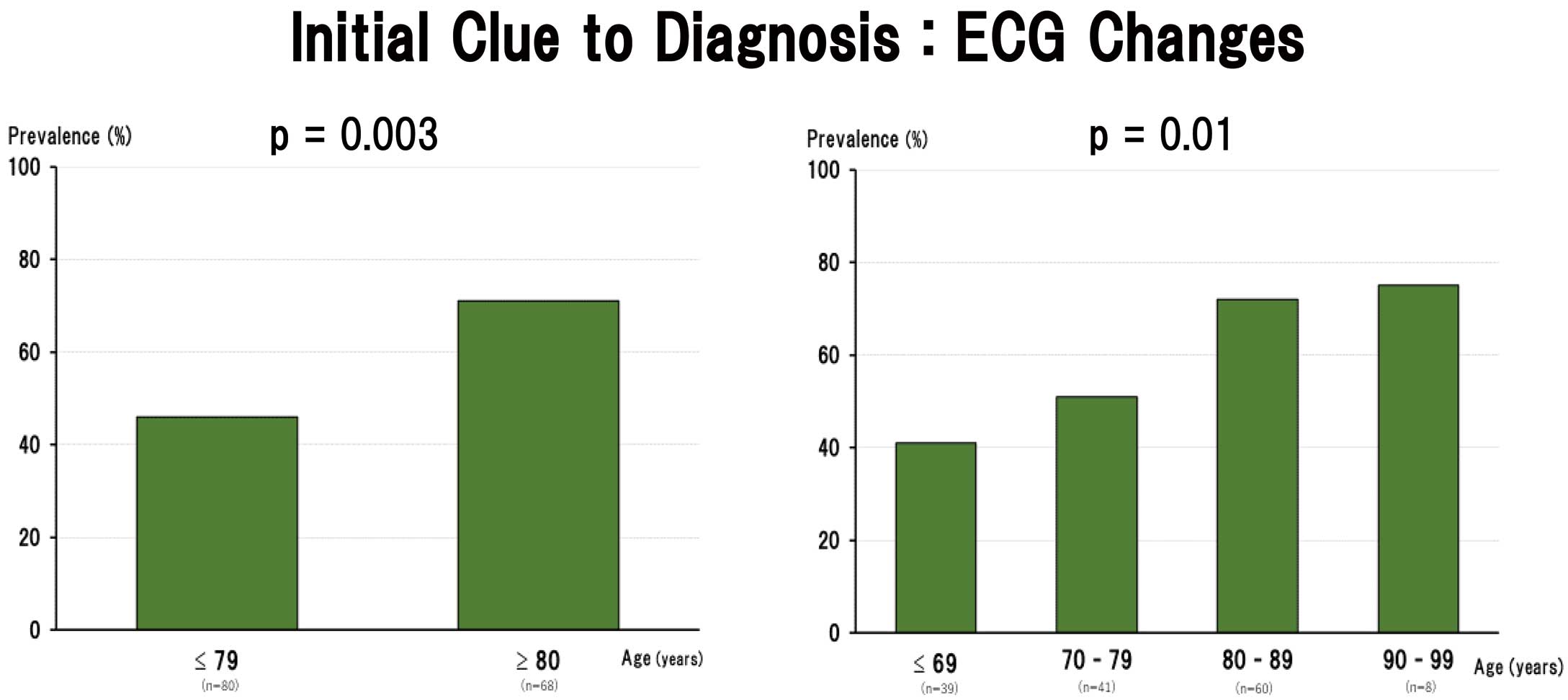

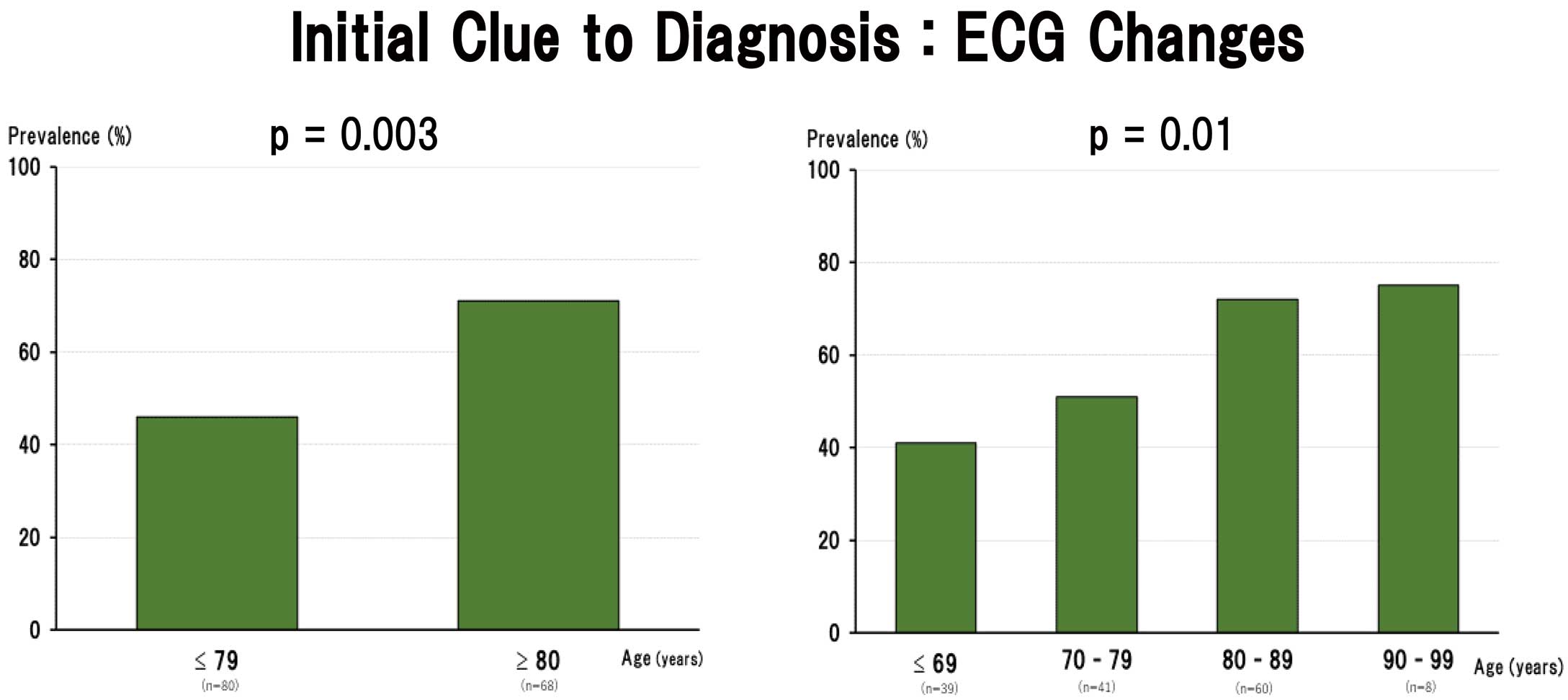

From 148 patients with TTS who underwent coronary angiography, 68 very elderly patients aged ≥80 years (octogenarians/nonagenarians) were compared with 80 younger patients aged ≤79 years. Emotional triggers of TTS were less frequent (7% vs. 19%; P=0.043), whereas physical triggers were more frequent (69% vs. 46%; P=0.005), in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years. As initial clues to the diagnosis, electrocardiogram changes were more frequent (71% vs. 46%; P=0.003) and chest pain and/or dyspnea were less common (25% vs. 51%; P=0.001) in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years. Twenty-nine patients had acute heart failure (AHF) as a complication. AHF was more frequently found in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years (29% vs. 11%, respectively; P=0.006). Cardiac death occurred in 2 octogenarians/nonagenarians; non-cardiac death occurred in 3 octogenarians/nonagenarians and in 2 patients aged ≤79 years.

Conclusions:

Emotional triggers of TTS were infrequent in octogenarians/nonagenarians with TTS. AHF was common and there was significant in-hospital all-cause mortality among octogenarians/nonagenarians.

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is an acute heart failure syndrome, often associated with a transient left ventricular dysfunction, that was first reported in 1990 by Sato et al.1

The clinical presentation of TTS is often indistinguishable from that of acute coronary syndrome, because patients present with chest pain and/or dyspnea, typical electrocardiogram (ECG) changes with ST segment elevation primarily in anterior and anterolateral leads, and mildly elevated levels of cardiac biomarkers, such as troponins.2–6

Angiography reveals left ventricular dysfunction, most commonly in the form of apical ballooning, despite the evidence of normal or non-obstructive coronary arteries.3–6,7

Although initially understood as a benign disorder, recent studies indicate that in-hospital outcomes of TTS are comparable to those of acute coronary syndrome, suggesting a much worse outcome than previously thought.8–10

Previous studies reported in-hospital all-cause mortality in TTS patients ranging from 1.8% to 6.4%.8,10–13

Older age and physical triggers of TTS are reported to be predictors of an adverse outcome.11

Although TTS occurs even in the very elderly, reports of TTS in the very elderly are limited mainly to sporadic case reports. Thus the clinical profile of TTS in the very elderly, including data on in-hospital outcomes, is not well known. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to clarify the clinical characteristics of octogenarians and nonagenarians with TTS.

Methods

Study Population

From 209 consecutive patients diagnosed with TTS who were hospitalized at Chikamori Hospital between January 2008 and March 2018, data for 148 patients who underwent emergency coronary angiography and who did not have total occlusion of the coronary artery were analyzed in the present retrospective study. All patients underwent diagnostic evaluation during acute presentation and received appropriate and best possible management during hospitalization. The definition of TTS was based primarily on the revised version of the Mayo Clinic diagnostic criteria,4,14

together with International Takotsubo (InterTAK) diagnostic criteria6

for this condition, as follows: (1) the presence of a transient regional wall motion abnormality of the left ventricle that extends beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution; (2) no significant obstructive coronary artery disease; (3) the presence of new ECG abnormalities (either ST segment elevation and/or T wave inversion) or modest elevations in cardiac biomarker levels; and (4) no myocarditis. However, the presence of coronary artery disease per se was not considered as an exclusion criterion.

The patient cohort was divided into 2 groups according to age: very elderly patients aged ≥80 years (octogenarians/nonagenarians) and patients aged ≤79 years. Patient data were evaluated for baseline characteristics, factors triggering TTS, comorbidities, changes in 12-lead ECG, echocardiographic transient regional wall motion abnormality, and in-hospital complications and outcomes. TTS was classified as apical, mid-ventricular, basal, or focal.8

The transient regional wall motion abnormalities associated with TTS were evaluated by follow-up echocardiography, which usually revealed a recovery in wall motion abnormalities. Clinical data, ECG and echocardiographic features, and angiographic findings of the patients were independently reviewed by 2 investigators experienced in diagnosing TTS. The diagnostic concordance between 2 investigators was based primarily on the Mayo Clinic and InterTAK diagnostic criteria (i.e., the presence of typical ECG changes and echocardiographic transient regional wall motion abnormality and the absence of total occlusion of the coronary artery).4,6,14

When eligibility for inclusion was uncertain, cases were reviewed by all members of the research team to reach consensus. All in-hospital events were assessed on the basis of a chart review. Causes of death were grouped as either cardiac or non-cardiac causes.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as the mean±SD, whereas those that were not normally distributed are presented as the median. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics are presented in

Tables 1

and

2. Mean patient age was 77±12 years. Of the 148 patients who underwent coronary angiography, 68 were very elderly (age ≥80 years; 60 octogenarians, 8 nonagenarians; see

Table 1) and 80 were aged ≤79 years (41 aged 70–79 years, 39 aged <70 years; see

Table 2). There were 120 female and 28 male patients. Among the 148 patients, 135 did not have significant coronary artery disease. Although 12 patients had single-vessel coronary artery disease and 1 patient had double-vessel coronary artery disease, none had total occlusion of the coronary artery suggestive of acute coronary syndrome.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Entire Patient Cohort, as well as Among Octogenarians/Nonagenarians and Patients Aged ≤79 Years Separately

| |

Total

(n=148) |

Age (years) |

P value |

| ≤79 (n=80) |

≥80 (n=68) |

| Age (years) |

77±12 |

68±10 |

85±4 |

|

| Sex |

| Female |

120 (81) |

61 (76) |

59 (87) |

0.104 |

| Male |

28 (19) |

19 (24) |

9 (13) |

0.104 |

| Trigger |

| Emotional |

20 (14) |

15 (19) |

5 (7) |

0.043 |

| Physical |

86 (58) |

37 (46) |

49 (72) |

0.005 |

| Infection |

29 |

10 |

19 |

0.031 |

| Respiratory |

19 |

8 |

11 |

0.263 |

| Urinary |

5 |

1 |

4 |

0.120 |

| Others |

5 |

1 |

4 |

0.212 |

| Stroke |

6 |

4 |

2 |

0.527 |

| Hemorrhage |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0.276 |

| Infarction |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0.658 |

| SAH |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0.189 |

| Fracture |

15 |

6 |

9 |

0.377 |

| Postoperative status |

9 |

5 |

4 |

0.926 |

| Respiratory diseases |

6 |

2 |

4 |

0.298 |

| Convulsion |

6 |

4 |

2 |

0.527 |

| Others |

15 |

6 |

9 |

0.249 |

| No trigger |

42 (28) |

28 (35) |

14 (21) |

0.053 |

| Vital signs |

| SBP (mmHg) |

137±31 |

134±30 |

141±32 |

0.681 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

80±19 |

81±18 |

78±20 |

0.050 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) |

88±21 |

88±19 |

87±23 |

0.881 |

| Initial clue to diagnosis |

| ECG |

85 (58) |

37 (46) |

48 (71) |

0.003 |

| ST elevation |

60 |

25 |

35 |

0.013 |

| T wave inversion |

20 |

10 |

10 |

0.696 |

| QT interval prolongation |

66 |

29 |

37 |

0.027 |

| Others |

5 |

2 |

3 |

0.521 |

| Chest pain/dyspnea |

58 (39) |

41 (51) |

17 (25) |

0.001 |

| Others |

5 (3) |

2 (3) |

3 (4) |

0.521 |

| Cardiac biomarkers |

| Hs-cTnT (ng/mL) |

0.594±0.534 |

0.532±0.417 |

0.566±0.636 |

0.517 |

| CK-MB (ng/mL) |

33±30 |

31±26 |

36±34 |

0.598 |

| BNP (pg/mL) |

584±761 |

499±691 |

684±830 |

0.079 |

| CRP (mg/dL) |

7.22±8.37 |

5.44±6.56 |

9.15±9.64 |

0.006 |

| Regional wall motion abnormality |

| Apical |

125 (84) |

67 (84) |

58 (85) |

0.796 |

| Mid-apex |

86 |

45 |

41 |

|

| Apex |

39 |

22 |

17 |

|

| Midventricular |

14 (9) |

7 (9) |

7 (10) |

0.749 |

| Basal |

3 (1) |

2 (1) |

1 (2) |

0.658 |

| Focal |

6 (4) |

4 (5) |

2 (3) |

0.527 |

| LVEF (%) |

47±10 |

48±11 |

46±9 |

|

| Acute intensive care treatment |

| IABP |

4 (3) |

4 (5) |

0 (0) |

0.062 |

| NIPPV |

1 (1) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

0.355 |

| Temporary pacemaker |

4 (3) |

2 (3) |

2 (3) |

0.869 |

| Medications during hospitalization |

| ACEI/ARB |

42 (28) |

18 (23) |

24 (35) |

0.085 |

| β-blocker |

23 (16) |

10 (13) |

13 (19) |

0.268 |

| CCB |

39 (26) |

23 (29) |

16 (24) |

0.472 |

| Diuretics |

39 (26) |

11 (14) |

28 (41) |

<0.001 |

| Concomitant malignant disease |

23 (16) |

15 (19) |

8 (12) |

0.242 |

| Complications |

| Heart failure |

29 (20) |

9 (11) |

20 (29) |

0.006 |

| VT/VF |

6 (4) |

4 (5) |

2 (3) |

0.527 |

| AF |

6 (4) |

1 (1) |

5 (7) |

0.061 |

| In-hospital mortality |

| Cardiac death |

2 (1) |

0 (0) |

2 (3) |

0.122 |

| Non-cardiac death |

5 (3) |

2 (3) |

3 (4) |

0.521 |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the mean±SD or n (%). ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; AF, atrial fibrillation; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CK-MB, creatine kinase MB; CRP, C-reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; Hs-cTnT, high-sensitive cardiac troponin T; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NIPPV, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; SBP, systolic blood pressure; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics for Specific Age Groups

| |

Age (years) |

P value |

| ≤69 (n=39) |

70–79 (n=41) |

80–89 (n=60) |

90–99 (n=8) |

| Age (years) |

60±9 |

75±3 |

84±3 |

92±2 |

|

| Sex |

| Female |

29 (74) |

32 (78) |

51 (85) |

8 (100) |

0.151 |

| Male |

10 (26) |

9 (22) |

9 (15) |

0 (0) |

0.151 |

| Trigger |

| Emotional |

7 (18) |

8 (20) |

5 (8) |

0 (0) |

0.131 |

| Physical |

16 (41) |

21 (51) |

43 (72) |

6 (75) |

0.011 |

| Infection |

4 |

6 |

17 |

2 |

0.112 |

| Respiratory |

4 |

4 |

10 |

1 |

0.717 |

| Urinary |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0.178 |

| Others |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0.216 |

| Stroke |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.326 |

| Hemorrhage |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.113 |

| Infarction |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0.929 |

| SAH |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.144 |

| Fracture |

1 |

5 |

8 |

1 |

0.236 |

| Postoperative status |

1 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

0.402 |

| Respiratory diseases |

1 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

0.547 |

| Convulsion |

4 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0.076 |

| Others |

2 |

4 |

7 |

2 |

0.401 |

| No trigger |

16 (41) |

12 (29) |

12 (20) |

2 (25) |

0.162 |

| Vital signs |

| SBP (mmHg) |

140±30 |

128±30 |

142±32 |

131±30 |

0.505 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

85±17 |

77±19 |

80±21 |

67±11 |

0.266 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) |

88±22 |

88±16 |

88±23 |

80±15 |

0.340 |

| Initial clue to diagnosis |

| ECG |

16 (41) |

21 (51) |

41 (68) |

7 (87) |

0.010 |

| ST elevation |

12 |

13 |

29 |

6 |

0.039 |

| T wave inversion |

3 |

7 |

9 |

1 |

0.606 |

| QT interval prolongation |

11 |

18 |

33 |

4 |

0.067 |

| Others |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

| Chest pain/dyspnea |

23 (59) |

18 (44) |

16 (27) |

1 (13) |

0.003 |

| Others |

0 (0) |

2 (5) |

3 (5) |

0 (0) |

|

| Cardiac biomarkers |

| Hs-cTnT (ng/mL) |

0.488±0.483 |

0.563±0.405 |

0.538±0.508 |

0.739±1.203 |

0.702 |

| CK-MB (ng/mL) |

31±29 |

30±23 |

33±27 |

55±65 |

0.492 |

| BNP (pg/mL) |

322±477 |

660±815 |

618±669 |

1,089±1,490 |

0.005 |

| CRP (mg/dL) |

5.54±7.48 |

5.35±5.70 |

8.71±9.12 |

12.3±13.1 |

0.470 |

| Regional wall motion abnormality |

| Apical |

31 (80) |

36 (88) |

51 (85) |

7 (87) |

0.771 |

| Mid-apex |

21 |

24 |

35 |

6 |

|

| Apex |

10 |

12 |

16 |

1 |

|

| Midventricular |

3 (8) |

4 (10) |

7 (12) |

0 (0) |

0.559 |

| Basal |

2 (5) |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

0.337 |

| Focal |

3 (8) |

1 (2) |

1 (1) |

1 (13) |

0.326 |

| LVEF (%) |

47±11 |

48±11 |

46±9 |

50±5 |

|

| Acute intensive care treatment |

| IABP |

4 (10) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.012 |

| NIPPV |

0 (0) |

1 (2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.460 |

| Temporary pacemaker |

0 (0) |

2 (5) |

2 (3) |

0 (0) |

0.354 |

| Medications during hospitalization |

| ACEI/ARB |

4 (10) |

14 (34) |

21 (35) |

3 (38) |

0.020 |

| β-blocker |

4 (10) |

6 (15) |

10 (17) |

3 (38) |

0.350 |

| Ca-antagonist |

9 (23) |

14 (34) |

13 (22) |

3 (38) |

0.454 |

| Diuretics |

5 (13) |

6 (15) |

22 (37) |

6 (75) |

<0.001 |

| Concomitant malignant disease |

10 (26) |

5 (12) |

7 (12) |

1 (13) |

0.284 |

| Complications |

| Heart failure |

3 (8) |

6 (15) |

16 (27) |

4 (50) |

0.015 |

| VT/VF |

2 (5) |

2 (5) |

2 (3) |

0 (0) |

0.820 |

| AF |

0 (0) |

1 (2) |

3 (5) |

2 (25) |

0.046 |

| In-hospital mortality |

| Cardiac death |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2) |

1 (12) |

0.173 |

| Non-cardiac death |

2 (5) |

0 (0) |

3 (5) |

0 (0) |

0.250 |

Data are presented as the mean±SD or n (%). Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Preceding emotional and physical triggers of TTS were identified in 106 patients (72%); emotional triggers were significantly less frequent in octogenarians/nonagenarians than among patients aged ≤79 years (7% vs. 19%; P=0.043;

Table 1; Figure 1), whereas physical triggers were significantly more frequent in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years (69% vs. 46%; P=0.005;

Figure 2). Of note, emotional triggers of TTS were not noted in nonagenarians. Most of the physical triggers were acute critical illnesses, including serious infection (e.g., pneumonia and sepsis), stroke, and bone fracture. In particular, serious infection was more common in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years (P=0.031;

Table 1). There were 42 patients (28%) in whom emotional and physical triggers of TTS were not identified.

Initial Clues to the Diagnosis of TTS

As initial clues to the diagnosis of TTS, 12-lead ECG changes, including ST segment elevation, T wave inversion, and prolongation in the QT interval, and subjective symptoms, such as chest pain and dyspnea, were evaluated (Table 1). Of the 148 patients, 85 (58%) were initially suspected to have TTS based on ECG changes, whereas 58 (39%) were initially suspected to have TTS based on symptoms of chest pain and/or dyspnea. The 85 patients who were suspected to have TTS based on ECG changes also had subjective symptoms other than chest pain and/or dyspnea, mostly related to acute critical illnesses at the time of admission. The 58 patients who were suspected to have TTS based on the presence of chest pain and/or dyspnea were later found to also have ECG changes indicative of TTS. There was a higher percentage of octogenarians/nonagenarians than patients aged ≤79 years who were initially suspected of having TTS based on ECG changes (71% vs. 46%; P=0.003;

Figure 3). In addition, octogenarians/nonagenarians were more frequently found to have ST segment elevation as an initial ECG change than patients aged ≤79 years (51% vs. 31%; P=0.013;

Table 1). The percentage of patients suspected to have TTS based subjective symptoms was significantly lower among octogenarians/nonagenarians than patients aged ≤79 years (25% vs. 51%; P=0.001;

Figure 4).

Apical ballooning occurred in 125 patients (84%); 86 patients had somewhat broader apical ballooning extending to the mid-ventricular segment and 39 patients had ballooning limited to the apical segment. Twenty-three patients (15%) had non-apical wall motion abnormalities: 14 patients with the mid-ventricular form, 6 with a focal form, and 3 with the basal form. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of apical ballooning between octogenarians/nonagenarians and patients aged ≤79 years (84% vs. 85%, respectively). The prevalence of non-apical wall motion abnormalities also did not differ significantly between in octogenarians/nonagenarians and patients aged ≤79 years (15% vs. 16%, respectively;

Table 1). All these abnormal left ventricular wall motions were transient and showed complete recovery at the time of patient discharge, with the exception of those patient who died during hospitalization.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was slightly reduced in total TTS population (Table 1). There was no significant difference in LVEF between octogenarians/nonagenarians and patients aged ≤79 years (Table 1), or among the 4 age groups (≤69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90–99 years;

Table 2).

Medications

Details of medications used during the course of hospitalization, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, β-blockers, calcium antagonists, and diuretics, are provided in

Tables 1

and

2. Although the prescription rate of these mediations were not high, the use of diuretics was more common in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years.

Complications

In all, 29 patients (20%) had acute heart failure as a complication (Table 1). Acute heart failure was more common in octogenarians/nonagenarians (n=20 patients; 29%) than in patients aged ≤79 years (n=9 patients; 11%; P=0.006;

Table 1). Among patients aged ≤79 years, 4 needed an intra-aortic balloon pump and 1 required non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. Across the entire study cohort, 12 (8%) patients experienced arrhythmic events: 6 experiencing ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation and 6 experiencing atrial fibrillation (Table 1). Although statistically not significant, atrial fibrillation seemed more common in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years. One patient developed left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, 7 patients had pericardial effusion, and 2 experienced left ventricular thrombus formation (Table 1).

In-Hospital Outcomes

In-hospital outcomes for the entire cohort, as well as for octogenarians/nonagenarians and aged ≤79 years separately, are summarized in

Table 1. In-hospital deaths were recorded for 7 patients (4.7%): cardiac deaths in 2 patients (1.4%) and non-cardiac deaths in 5 patients (3.4%). The rate of all-cause mortality in octogenarians/nonagenarians with TTS was 7.4%, compared with 2.5% in patients aged ≤79 years (NS). With regard to preceding triggers of TTS in relation to in-hospital deaths, emotional triggers were found in 1 patient and physical triggers were found in 6 patients. The 2 cardiac deaths occurred in octogenarians/nonagenarians (1 patient with heart failure and another with cardiac rupture), whereas the 5 non-cardiac deaths occurred in 3 octogenarians/nonagenarians (1 patient with pneumonia, 1 with septic shock, and 1 with lymphoma) and 2 patients aged ≤79 years ( 1 patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage and another with lung cancer). Of the 2 patients with recorded cardiac death, 1 octogenarian had concomitant sick sinus syndrome and 1 nonagenarian had severe aortic stenosis.

Discussion

Emotional Triggers of TTS Are Uncommon in Octogenarians/Nonagenarians

The prevalence of emotional stressors as triggering factors for TTS in all patients was 15%, which is somewhat lower than that reported in previous studies.6,8,15

The most interesting and novel finding of the present study is that the prevalence of emotional triggers was particularly uncommon in octogenarians/nonagenarians compared with patients aged ≤79 years. Furthermore, emotional triggers were not found in 8 nonagenarians. To date, a low prevalence of emotional triggers of TTS with advancing age has not been reported, probably because there have been few studies investigating the very elderly, such as octogenarians and nonagenarians, with TTS. The reason for this finding is unclear, although it is possible that advancing age itself, together with declining cognitive function, may explain why emotional triggers are uncommon among octogenarians and nonagenarians with TTS. Although the accuracy of history taking among the very elderly in an emergency setting can also be questioned, in Chikamori Hospital several emergency physicians initially take a patient’s history, carefully and independently, followed by detailed history taking by cardiology residents, nurses, and attending physicians after admission. These processes make it unlikely that the history taking was inaccurate in the present study.

Physical stressors as triggers for TTS were previously reported to be more common than emotional triggers.6,8

In the present study, physical triggers were found to be common in octogenarians and nonagenarians, with 69% of octogenarians and nonagenarians having physical stressors as triggers of TTS. Most of these physical triggers were acute critical illnesses, including serious infection, stroke, bone fracture, and other acute conditions. The overall prevalence of physical triggers was 57%, which is more frequent than reported previously.6,8

Although the reason for this high prevalence of physical triggers in the present study is uncertain, it could be explained, in part, by study setting: Chikamori Hospital has a large emergency department and accepts a large number of patients with acute critical illnesses. In the present study, 28% of patients did not have any triggers for TTS, although the lack of any triggers for TTS was somewhat less prevalent among octogenarians/nonagenarians.

ECG Changes Are Essential Initial Clues to the Diagnosis of TTS in Octogenarians/Nonagenarians

Subjective symptoms, such as chest pain and/or dyspnea, were found in 39% of the entire TTS patient population in this study, and were an important initial clue to the diagnosis. However, the prevalence of subjective symptoms was significantly lower in octogenarians/nonagenarians compared with patients aged ≤79 years. It could be speculated that concomitant nervous system conditions with impaired consciousness, such as acute ischemic stroke, and subclinical cognitive decline are responsible for the reduced prevalence of subjective symptoms among octogenarians/nonagenarians. However, the incidence of acute ischemic stroke in the present study did not differ significantly between octogenarians/nonagenarians and patients aged ≤79 years.

The initial ECG is generally abnormal in most patients with TTS, showing ST segment elevation, T wave inversion, or both.6,8,16–19

These ECG changes were also found in most of the present TTS patient population. However, its prevalence as an initial clue to the diagnosis of TTS was significantly higher among octogenarians/nonagenarians than among patients aged ≤79 years.

Therefore, one of the clinical implications of this study is that it is advisable for all patients with acute critical illness, particularly octogenarians and nonagenarians, to undergo an ECG examination at the time of an acute presentation.

Transient Regional Wall Motion Abnormalities

In this study, apical ballooning was found in 84% of the total patient population. This prevalence of apical ballooning is consistent with most previous reports, including a report by Templin et al, who reported apical ballooning in 81.7% of their patients.8

Non-apical forms of TTS have been reported to have a different clinical phenotype.20,21

Specifically, these patients are younger and more often have neurologic conditions. However, in the present study there was no significant difference in the prevalence of non-apical forms of TTS among the 4 different age groups (≤69, 70–79, 80–89, and 90–99 years). The incidence of stroke also did not differ significantly among these 4 age groups.

In-Hospital Complications and Outcomes

Elderly patients are at higher risk of developing TTS and related complications.10,22

The rate of major adverse cardiovascular events during hospitalization was reported to be as high as 21.8–23.3%.8,12

In the Takotsubo Italian Network, older adults (age ≥75 years) had higher rates of in-hospital complications and in-hospital mortality.23

The incidence of major complications, such as acute hear failure (20%) and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (4%), in the present study was consistent with that in several previous reports.5,8,10

However, acute heart failure as a complication was more often detected in octogenarians/nonagenarians than in patients aged ≤79 years.

Several clinical variables have been reported to affect the prognosis of patients with TTS, including blood pressure and heart rate on admission,24

right ventricular wall motion abnormality,25

reduced LVEF,26

supraventricular arrhythmia,27

cardiogenic shock,28

cardiac arrest,29

and the administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.30

However, most of these variables were assessed in relation to short- and long-term prognoses. In the present study, because of its cross-sectional design, in-hospital mortality was solely evaluated and there was no intention to evaluate long-term prognosis. Nevertheless, blood pressure and heart rate on admission, LVEF, and the administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors did not differ significantly between octogenarians/nonagenarians and patients aged ≤79 years. The use of diuretics was common in octogenarians and nonagenarians, probably because of the increased incidence of heart failure.

In-hospital all-cause mortality was previously reported to range from 1.8% to 6.4%.8,11–13

In the present study, 4.7% of the entire TTS patient population died, which is consistent with the rate reported previously.8,11–13

The rate of all-cause mortality in octogenarians and nonagenarians with TTS was 7.4%. Cardiac death occurred in 1 octogenarian with concomitant sick sinus syndrome, and in 1 nonagenarian with severe aortic stenosis. Therefore, cardiac death may occur particularly when serious cardiac comorbidities are present.

Study Limitations

The limitations of the present study include its retrospective design and cross-sectional nature, as well as it being performed in a single institution. In addition, although the study enrolled 148 patients with TTS, the number of patients is modest compared with numbers in recent multicenter studies. However, there have been no such previous studies as the present study, in which nearly half the patients were octogenarians and nonagenarians.

Conclusions

A novel and most interesting finding of this present study is that emotional triggers of TTS became infrequent with advancing age, particularly in octogenarians and nonagenarians with TTS. As initial clues to the diagnosis of TTS, the detection of typical ECG changes was important in octogenarians and nonagenarians, which also suggests the importance of getting an ECG recording in all patients presenting with an acute critical illness. Acute heart failure was common and there was significant all-cause in-hospital mortality among octogenarians and nonagenarians.

Acknowledgments

We thank Junya Komatsu for his assistance in statistical analysis.

Sources of Funding

This study did not receive any specific funding.

Disclosures

H.K. is a member of

Circulation Reports’ Editorial Team. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

IRB Information

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chikamori Hospital (Reference no: 368).

References

- 1.

Sato H, Tateishi H, Dote K, Uchida T, Ishihara M. Tako-tsubo-like left ventricular dysfunction due to multivessel coronary spasm. In: Kodama K, Haze K, Hori M, editors. Clinical aspect of myocardial injury: From ischemia to heart failure. Tokyo: Kagakuhyoronsha Publishing, 1990; 56–64 [in Japanese].

- 2.

Sharkey SW, Lesser JR, Zenovich AG, Maron MS, Lindberg J, Longe TF, et al. Acute and reversible cardiomyopathy provoked by stress in women from the United States. Circulation 2005; 111: 472–479.

- 3.

Bybee KA, Prasad A. Stress-related cardiomyopathy syndromes. Circulation 2008; 118: 379–409.

- 4.

Scantlebury DC, Prasad A. Diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy: Mayo Clinic criteria. Circ J 2014; 78: 2129–2139.

- 5.

de Chazal HM, Del Buono MG, Keyser-Marcus L, Ma L, Moeller FG, Berrocal D, et al. Stress cardiomyopathy diagnosis and treatment: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72: 1955–1971.

- 6.

Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, Sharkey S, Dote K, Akashi YJ, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (Part I): Clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 2032–2046.

- 7.

Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, Oh-mura N, Kimura K, Owa M, et al. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: A novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38: 11–18.

- 8.

Templin C, Ghadri HR, Diekmann J, Napp LC, Bataiosu DR, Jaguszewski M, et al. Clinical features and outcome of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 929–938.

- 9.

Pelliccia F, Pasceri V, Patti G, Tanzilli G, Speciale G, Gaudio C, et al. Long-term prognosis and outcome predictors in takotsubo syndrome: A systematic review and meta-regression study. JACC Heart Fail 2019; 7: 143–154.

- 10.

Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, Sharkry S, Dote K, Akashi YJ, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (Part II): Diagnostic workup, outcome, and management. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 2047–2062.

- 11.

Almendro-Delia M, Nunez-Gil IJ, Lobo M, Andres M, Vedia O, Sionis A, et al. Short- and long-term prognostic relevance of cardiogenic shock in takotsubo syndrome: Results from the RETAKO registry. JACC Heart Fail 2018; 6: 928–936.

- 12.

Murakami T, Yoshikawa T, Maekawa Y, Ueda T, Isogai T, Sakata K, et al. Gender differences in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: Multi-center registry from Tokyo CCU network. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0136655.

- 13.

Stiemaier T, Santoro F, El-Battrawy I, Möller C, Graf T, Novo G, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of diabetes in takotsubo syndrome: Insights from the international, multicenter GEIST registry. Diabetes Care 2018; 41: 1084–1088.

- 14.

Prasad A, Lerman A, Rihal CS. Apical ballooning syndrome (tako-tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): A mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008; 115: 408–417.

- 15.

Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JAC, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 539–548.

- 16.

Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, Sechtem U, Citro R, Underwood SR, et al. Current state of knowledge on takotsubo syndrome: A position statement from the Task Force on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 8–27.

- 17.

Sharkey SW, Maron BJ. Epidemiology and clinical profile of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2014; 78: 2119–2128.

- 18.

Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Nakamura S, et al. Time course of electrocardiographic changes in patients with tako-tsubo syndrome: Comparison with acute myocardial infarction with minimal enzymatic release. Circ J 2004; 68: 77–81.

- 19.

Kosuge M, Kimura K. Electrocardiographic findings of takotsubo cardiomyopathy as compared with those of anterior myocardial infarction. J Electrocardiol 2014; 47: 684–689.

- 20.

Ghadri JR, Camman VL, Napp LC, Jurisic S, Diekmann J, Bataiosu DR, et al. International Takotsubo (InterTAK) Registry. Differences in the clinical profile and outcomes of typical and atypical takotsubo syndrome: Data from the International Takotsubo Registry. JAMA Cardiol 2016; 1: 335–340.

- 21.

Stiermaier T, Moeller C, Oehler K, Desch S, Graf T, Eitel C, et al. Long-term excess mortality in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: Predictors, causes and clinical consequenes. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 650–656.

- 22.

Santoro F, Nunez Gil IJ, Stiermaier T, El-Battrawy I, Guerra F, Novo G, et al. Assessment of the German and Italian stress cardiomyopathy score for risk stratification for in-hospital complications in patients with takotsubo syndrome. JAMA Cardiol 2019; 4: 892–899.

- 23.

Citro R, Rigo F, Previtali M, Ciampi Q, Canterin FA, Provenza G, et al. Differences in clinical features and in-hospital outcomes of older adults with tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 93–98.

- 24.

Böhm M, Cammann VL, Ghadri JG, Ukena C, Gili S, Di Vece D, et al. Interaction of systolic blood pressure and resting heart rate with clinical outcomes in takotsubo syndrome: Insights from the International Takotsubo Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 1021–1030.

- 25.

Kagiyama N, Okura H, Tamada T, Imai K, Yamada R, Kume T, et al. Impact of right ventricular involvement on the prognosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 17: 210–216.

- 26.

Citro R, Radano I, Parodi G, Di Vece D, Zito C, Novo G, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with takotsubo syndrome presenting with severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 781–789.

- 27.

Jesel L, Berthon C, Messas N, Lim HS, Girardey M, Marzak H, et al. Atrial arrhythmias in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: Incidence, predictive factors, and prognosis. Europace 2019; 21: 298–305.

- 28.

Di Vece D, Citro R, Cammann VL, Kato K, Gili S, Szawan KA, et al. Outcomes associated with cardiogenic shock in takotsubo syndrome. Results from the International Takotsubo Registry. Circulation 2019; 139: 413–415.

- 29.

Gili S, Cammann VL, Schlossbauer SA, Kato K, D’Ascenzo F, Di Vece D, et al. Cardiac arrest in takotsubo syndrome: Results from the InterTAK Registry. Eur Heart J 2019; 40: 2142–2151.

- 30.

Singh K, Carson K, Usmani Z, Sawhney G, Shah R, Horowitz J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence and correlates of recurrence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2014; 174: 696–701.