Abstract

Background: Recent guidelines for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) recommend prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin for ACS patients. However, there is no clear evidence to support this. We investigated the benefits and harms of prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals in patients with suspected ACS.

Methods and Results: We searched the PubMed database and used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of evidence. Three retrospective studies for aspirin and 1 for nitroglycerin administered in the prehospital setting to patients with acute myocardial infarction were included. Prehospital aspirin administration was associated with significantly lower 30-day and 1-year mortality compared with aspirin administration after arrival at hospital, with odds ratios (OR) of 0.59 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35–0.99) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.36–0.62), respectively. Prehospital nitroglycerin administration was also associated with significantly lower 30-day and 1-year mortality compared with no prehospital administration (OR 0.34 [95% CI 0.24–0.50] and 0.38 [95% CI 0.29–0.50], respectively). The certainty of evidence was very low in both systematic reviews.

Conclusions: Our systematic reviews suggest that prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals is beneficial for patients with suspected ACS, although the certainty of evidence is very low. Further investigation is needed to determine the benefit of the prehospital administration of these agents.

Aspirin and nitroglycerin have been recommended as initial drug therapy for acute coronary syndrome (ACS).1 Current guidelines for ACS recommend that aspirin is given as soon as possible to ACS patients without contraindications.1–3 Aspirin has been shown to reduce mortality in ACS.4 Furthermore, its effect has been shown to be greater when administered earlier after symptom onset.5 Nitroglycerin is similarly widely used for the effective treatment of the chest pain of angina or suspected ACS. Studies conducted before the era of reperfusion therapy reported the effectiveness of nitroglycerin in reducing infarct size and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who were admitted to the cardiac care unit within 4 h of onset.6,7

However, no studies have examined whether prehospital administration of aspirin or nitroglycerin to patients with suspected ACS improves clinical outcomes compared with no administration. The effect of early administration of both or one of these drugs is based on data from patients who were administered these drugs after arrival at the emergency department,4,6,7 rather than in the prehospital setting. In addition, the effects of nitroglycerin administration were extrapolated from results of intravenous nitroglycerin administration.6,7 The 2010 and 2015 Japan Resuscitation Council (JRC) guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the routine administration of aspirin and/or nitroglycerin to patients with a suspected ACS in the prehospital setting.8,9

Therefore, we assessed the benefits and harms of prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals to patients with suspected ACS in recent studies. The findings of the present study are very important to fill the knowledge gaps in the 2010 and 2015 JRC guidelines,8,9 and the 2018 Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) guidelines for ACS.1

Methods

The JRC ACS Task Force for Guideline 2020 was established by the JCS, the Japanese Association of Acute Medicine, and the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine. The Task Force established 12 clinically relevant questions; in this paper we assess the following 2 clinical questions (CQ): should patients with suspected ACS be administered aspirin by non-physician healthcare professionals in the prehospital setting (CQ1); and should patients with suspected ACS be administered nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals in the prehospital setting (CQ2)?

After discussion between JRC ACS Task Force and the Guidelines Editorial Committee, the Population Intervention Comparator Outcome Study design and Time frame (PICOST) was to guide the systematic review search, as described below.

CQ1: Aspirin

P (patients): adult patients with suspected ACS in the prehospital setting

I (intervention): prehospital administration of aspirin by non-physician healthcare professionals

C (comparisons, controls): no prehospital administration of aspirin by non-physician healthcare professionals

O (outcomes): mortality, intracranial bleeding, reinfarction, revascularization, stroke, major hemorrhage, infarct size, and electrocardiogram (ECG) resolution ≥50%

S (study designs): randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies published in English

T (time frame): studies published before August 14, 2020.

CQ2: Nitroglycerin

P (patients): adult patients with suspected ACS in the prehospital setting

I (intervention): prehospital administration of nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals

C (comparisons, controls): no prehospital administration of nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals

O (outcomes): mortality

S (study designs): RCTs and non-randomized studies published in English

T (time frame): studies published before July 15, 2020.

The systematic reviews and meta-analyses in this study were performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.10,11

Search Strategies, Study Selection, and Inclusion Criteria

A systematic search of published reports the PubMed database was conducted to retrieve relevant articles for the reviews. We searched for full-text RCTs and observational studies in humans. We used a combination of key terms and established a full search strategy (Supplementary Figure). Our study population of interest was adult patients with suspected ACS in the prehospital setting. We did not restrict our analyses by country, but only included studies published in English. We sought to determine whether adult patients with suspected ACS should be administered aspirin by non-physician healthcare professionals in the prehospital setting. Outcomes were compared between patients with and without aspirin administration in the prehospital setting. The critical outcomes of the CQ1 study were: (1) mortality; (2) intracranial bleeding; (3) reinfarction; (4) revascularization; and (5) stroke. The important outcome of the CQ1 study was major hemorrhage. Similar comparisons were made for nitroglycerin (patients with vs. without prehospital nitroglycerin administration); the only critical outcome for the CQ2 study was mortality.

Assessment of the Risk of Bias

The Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool (RevMan 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for appraising RCTs and non-RCTs. An experienced pair of reviewers (N.N. and T.Y.) independently appraised the risk of bias of all included studies. Studies were categorized as having a “low”, “unclear”, or “high” risk of bias in each domain. The risk of bias for each element was considered “high” when bias was present and likely to affect the outcomes and “low” when bias was not present or present but unlikely to affect the outcomes.

Data Extraction and Management

The following data were extracted: author(s), title, journal name, year of publication, website (URL), and abstract. Two independent reviewers (N.N., T.Y.) screened the abstracts and titles of the studies and subsequently reviewed the full-text articles. Disagreements were reconsidered and discussed until a consensus was reached. The full text of articles included in the final selection were independently reviewed by another 2 reviewers (Y.T., M.K.). Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (H.N.).

Rating the Certainty of Evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tool to rate the certainty of the evidence as to whether patients with suspected ACS should be administered aspirin and nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals in the prehospital setting.12,13 The certainty of the evidence was assessed as “high,” “moderate”, “low”, or “very low” by evaluating the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

Statistical Analysis

The results were summarized using a random effects model to facilitate the pooling of estimates of the treatment effects. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used for dichotomous outcomes. Heterogeneity between trials for each outcome was evaluated using the I2

statistic to quantify inconsistency,14 and was considered significant if the reason for heterogeneity could not be explained and if the I2

value was ≥50%. We generated a funnel plot to investigate potential publication bias. The estimates for each outcome were pooled using a random effects model. The meta-analysis was performed based on all published data and data made available to us. All analyses were undertaken using Review Manager software (RevMan 5.3).

Results

CQ1: Aspirin

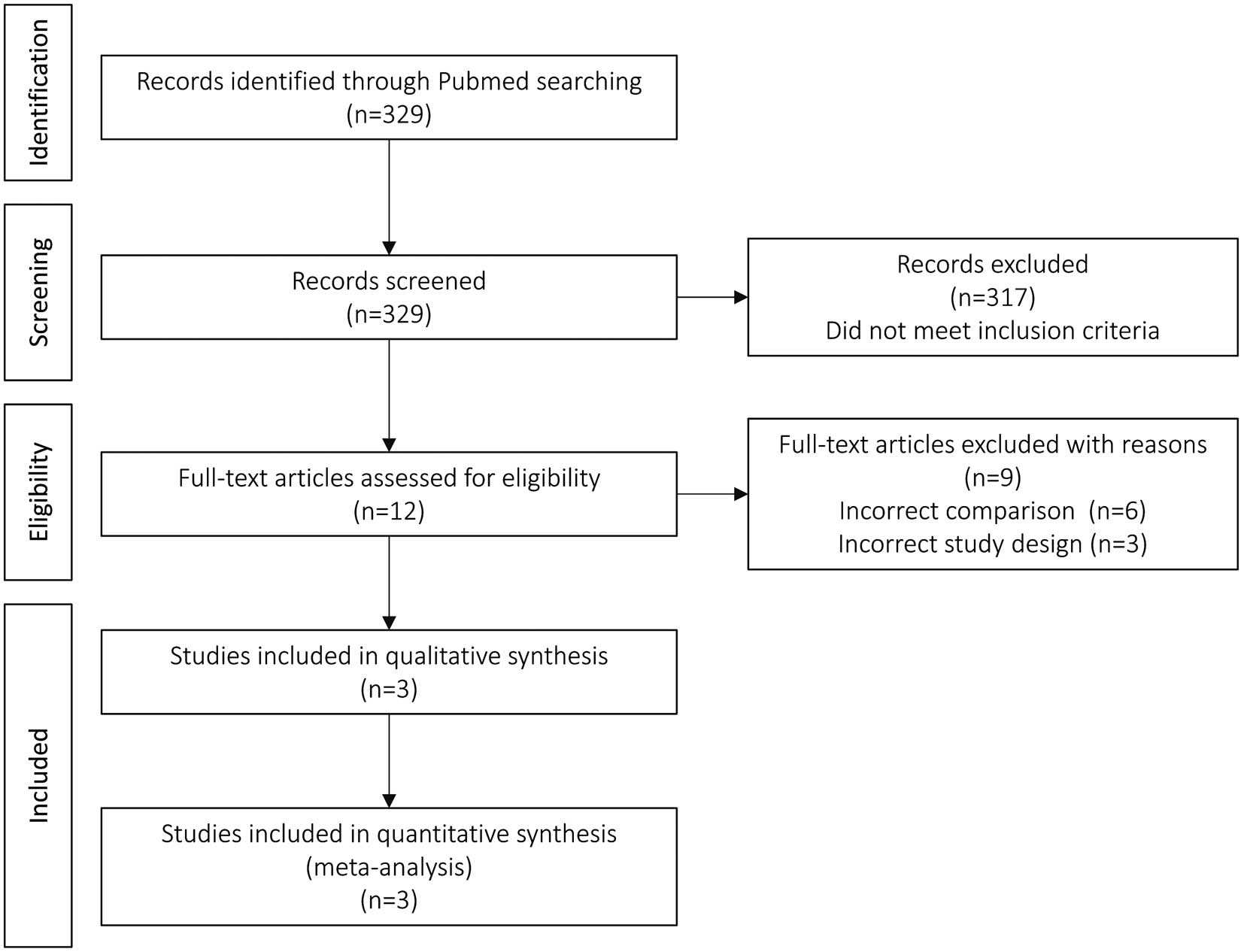

Literature Search The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. We identified 329 citations through the database search. Twelve studies were assessed for eligibility based on the titles and abstracts. After full-text assessment, 3 citations were included in the meta-analysis.15–17

Study Characteristics No RCTs were identified, and all 3 identified citations were non-RCTs.15–17 Details of the individual studies are presented in Table 1. Analysis of the observational study reported by Strandmark et al17 became possible by asking the authors for detailed data not described in the original paper.

Table 1. Study Characteristics and Findings

Authors,

Year |

Patients |

Comparison |

No.

patients |

Mortality |

Reinfarction |

Stroke |

Major

hemorrhage |

| 30-day |

1-year |

| Aspirin |

Zijlstra

et al15

(2002) |

1,702 patients

with STEMI |

Administration of aspirin with

heparin before transportation

to hospital |

860 |

26 (3.0) |

|

|

1 (0.1) |

43 (5.0) |

Administration of aspirin with

heparin in the emergency

room of the hospital |

842 |

24 (2.9) |

|

|

3 (0.4) |

59 (7.0) |

Barbash

et al16

(2002) |

922 patients

with STEMI |

Prehospital administration of

aspirin (self-administration or

administration in the mobile

CCU) |

338 |

16 (4.9) |

|

14 (4.1) |

|

|

In-hospital administration of

aspirin (administration in the

emergency room or CCU) |

584 |

64 (11.1) |

|

17 (2.9) |

|

|

Strandmark

et al17

(2015) |

1,726 patients

with AMI |

Prehospital administration of

aspirin by EMS |

995 |

51 (5.1) |

102 (9.4) |

|

|

|

No prehospital administration

of aspirin by EMS |

731 |

72 (10.1) |

143 (18.6) |

|

|

|

| Nitroglycerin |

Strandmark

et al17

(2015) |

1,726 patients

with AMI |

Prehospital administration of

nitroglycerin by EMS |

1,142 |

52 (4.6) |

|

|

|

|

No prehospital administration

of nitroglycerin by EMS |

584 |

71 (12.2) |

|

|

|

|

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as n (%). AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CCU, cardiac care unit; EMS, emergency medical services; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Critical Outcomes Forest plots of the critical outcomes with the risk of bias are shown in Figure 2. For the critical outcome of 30-day mortality, 3 observational studies were identified.15–17 Among 4,350 patients, 93 of 2,193 patients (4.2%) in the prehospital administration group and 160 of 2,157 patients (7.4%) in the control group died within 30 days. For the critical outcome of 1-year mortality, 1 observational study was identified.17 In that study, among 1,726 patients, 102 of 995 patients (10.3%) in the prehospital administration group and 143 of 731 patients (19.6%) in the control group died within 1 year. The prehospital administration group had significantly lower 30-day and 1-year mortality than the control group (OR 0.59 [95% CI: 0.35–0.99; P<0.01] and 0.47 [95% CI: 0.36–0.62; P<0.01], respectively). For the critical outcome of reinfarction, 1 observational study was identified.16 Among the 922 patients in that study, reinfarction was observed in 14 of 338 patients (4.1%) in the prehospital administration group and 17 of 584 patients (2.9%) in the control group. For the critical outcome of stroke, 1 observational study was identified.15 Among the 1,702 patients in that study, stroke was observed in 1 of 860 patients (0.1%) in the prehospital administration group and 3 of 842 patients (0.4%) in the control group. For the important outcome of major hemorrhage, 1 observational study was identified.15 In that study, among 1,702 patients, major hemorrhage was observed in 43 of 860 patients (5.0%) in the prehospital administration group and 59 of 842 patients (7.0%) in the control group. For the critical outcome of reinfarction and stroke, and for the important outcome of major hemorrhage, there were no significant differences between the prehospital administration and control groups. There were no clinical papers assessing the outcome of intracranial bleeding, revascularization, infarct size, or ECG resolution ≥50%.

Certainty of Evidence We assessed the certainty of evidence for each outcome and present a summary in Table 2. We judged the level of evidence to be very low because: patient backgrounds differed between the 2 groups; I2

>50% and variation in point estimation; the study population was limited to cases finally diagnosed with AMI; the prehospital administration of aspirin was not performed by a healthcare professional other than a physician; the number of cases was small; and the 95% CI crosses the threshold of significant benefits and significant harm.

Table 2. Evidence Profile Table for Aspirin

| No. studies |

Certainty assessment |

No. patients (%) |

Effect |

Certainty |

Importance |

| Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other

considerations |

Prehospital |

In-hospital |

Relative

(95% CI) |

Absolute

(95% CI) |

| 30-day mortality15–17 |

| 3 |

Observational

studies |

Very seriousA |

SeriousB |

Very seriousC,D |

SeriousE |

None |

93/2,193 (4.2) |

160/2,157 (7.4) |

OR 0.61

(0.38 to 0.98) |

28 fewer per 1,000

(from 45 fewer to 1 fewer) |

⊕○○○

Very low |

Critical |

| 1-year mortality17 |

| 1 |

Observational

study |

Very seriousA |

Not serious |

Very seriousC |

SeriousE |

None |

102/995 (10.3) |

143/731 (19.6) |

OR 0.52

(0.41 to 0.66) |

83 fewer per 1,000

(from 105 fewer to 57 fewer) |

⊕○○○

Very low |

Critical |

| Reinfarction16 |

| 1 |

Observational

study |

Very seriousA |

Not serious |

Very seriousC,D |

SeriousE,F |

None |

14/338 (4.1) |

17/584 (2.9) |

OR 1.42

(0.71 to 2.85) |

12 more per 1,000

(from 8 fewer to 50 more) |

⊕○○○

Very low |

Critical |

| Stroke15 |

| 1 |

Observational

study |

Very seriousA |

Not serious |

Very seriousC,D |

SeriousE,F |

None |

1/860 (0.1) |

3/842 (0.4) |

OR 0.33

(0.03 to 3.13) |

2 fewer per 1,000

(from 3 fewer to 8 more) |

⊕○○○

Very low |

Critical |

| Major hemorrhage15 |

| 1 |

Observational

study |

Very seriousA |

Not serious |

Very seriousC,D |

SeriousE |

None |

43/860 (5.0) |

59/842 (7.0) |

OR 0.71

(0.49 to 1.04) |

19 fewer per 1,000

(from 34 fewer to 3 more) |

⊕○○○

Very low |

Important |

Reasons for downgrading are as follows: Apatient background differs between 2 groups; BI2 >50% and variation in point estimation; Cstudy population is limited to patients finally diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction; Dprehospital administration of aspirin was not performed by a healthcare professional other than a physician; Esmall number of cases; and F95% confidence interval (CI) crosses the threshold of significant benefits and significant harm. OR, odds ratio.

Literature Search The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 3. We identified 139 citations through the database search. Only one citation was assessed for eligibility based on the titles and abstracts. After a full-text assessment, this citation was excluded because of no outcomes of interest. Conversely, in the process of searching for evidence for prehospital administration of aspirin, we found a single-center retrospective observational study17 that evaluated prehospital pharmacological intervention in AMI. We were able to obtain detailed data on nitroglycerin administration from the authors, which enabled us to examine the data. We included the data from the authors of that paper in the meta-analysis.

Study Characteristics There were no RCTs, and only 1 non-RCT was identified.17 The detailed characteristics of this study are presented in Table 1.

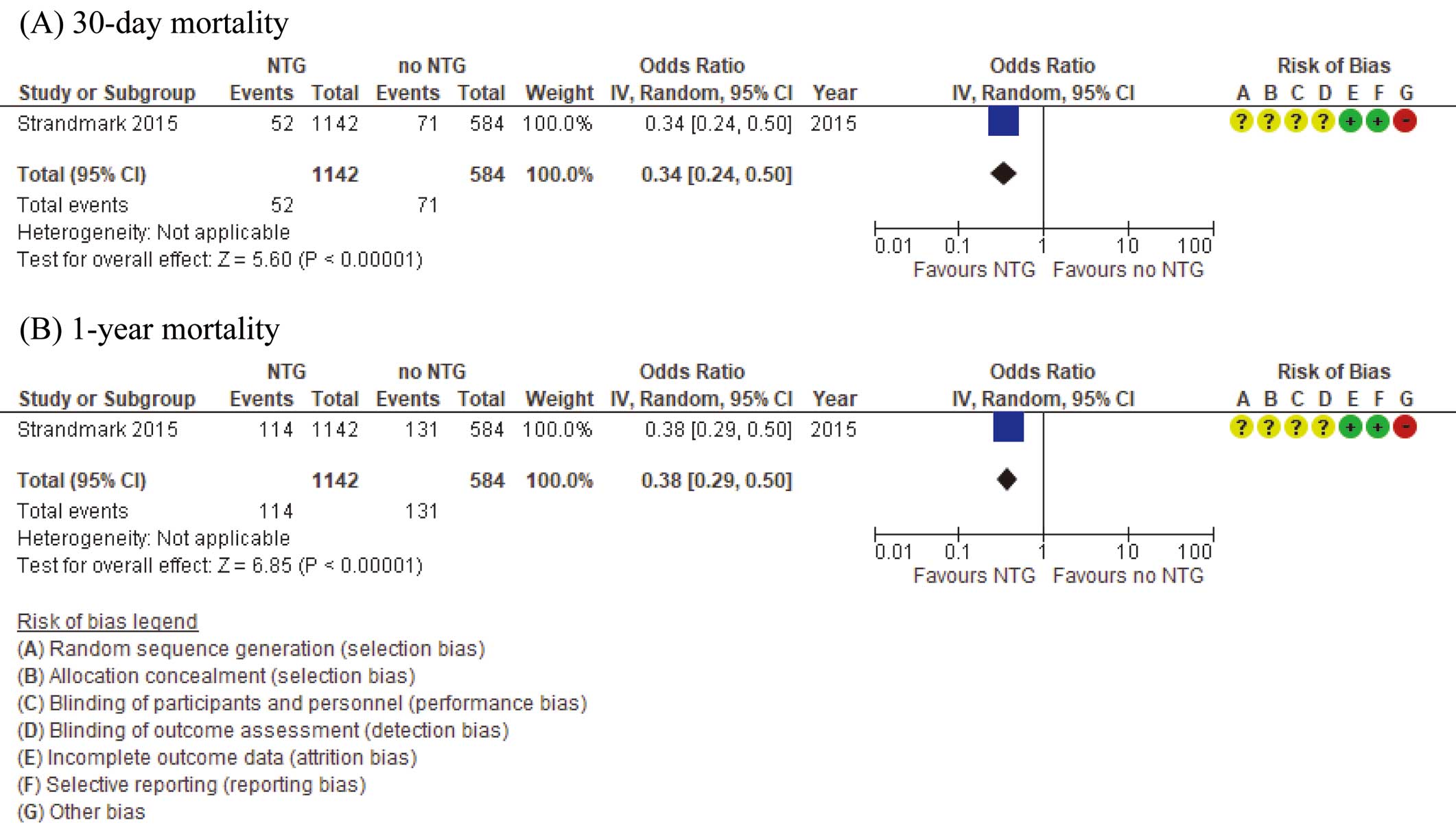

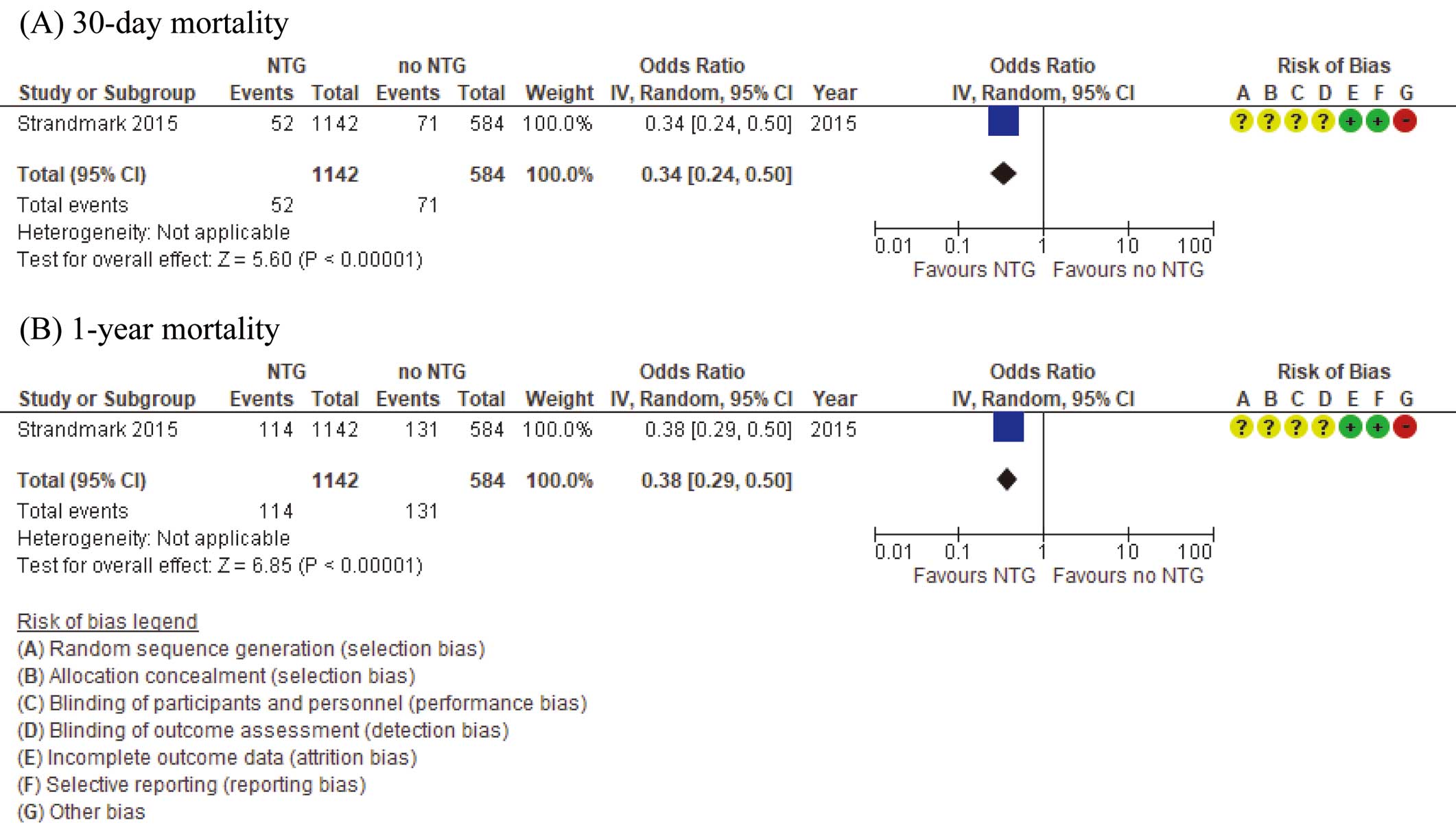

Critical Outcomes Forest plots of the critical outcomes with the risk of bias are shown in Figure 4. For the critical outcome of 30-day and 1-year mortality, only one observational study was identified.17 Among the 1,726 patients in that study, 52 of 1,142 patients (4.6%) in the prehospital administration group and 71 of 584 patients (12.2%) in the control group died within 30 days. With regard to 1-year mortality, 114 of 1,142 patients (10.0%) in the prehospital administration group and 131 of 584 patients (22.4%) in the control group died within 1 year. The prehospital administration group had significantly lower 30-day and 1-year mortality than the control group (OR 0.34 [95% CI: 0.24–0.50; P<0.01] and 0.38 [95% CI: 0.29–0.50; P<0.01], respectively).

Certainty of Evidence We assessed the certainty of evidence for each outcome and present a summary in Table 3. We judged the level of evidence to be very low because patient backgrounds differed between the 2 groups, the study population was limited to patients finally diagnosed with AMI, and there was only a small number of cases.

Table 3. Evidence Profile Table for Nitroglycerin

| No. studies |

Certainty assessment |

No. patients (%) |

Effect |

Certainty |

Importance |

| Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency |

Indirectness |

Imprecision |

Other

considerations |

Prehospital |

No prehospital |

Relative

(95% CI) |

Absolute

(95% CI) |

| 30-day mortality17 |

| 1 |

Observational

study |

Very seriousA |

Not serious |

SeriousB |

SeriousC |

None |

52/1,142 (4.6) |

71/584 (12.2) |

OR 0.34

(0.24 to 0.50) |

77 fewer per 1,000

(from 57 fewer to 89 fewer) |

⊕○○○

Very low |

Critical |

| 1-year mortality17 |

| 1 |

Observational

study |

Very seriousA |

Not serious |

SeriousB |

SeriousC |

None |

114/1,142 (10.0) |

131/584 (22.4) |

OR 0.38

(0.29 to 0.50) |

125 fewer per 1,000

(from 147 fewer to 98 fewer) |

⊕○○○

Very low |

Critical |

Reasons for downgrading are as follows: Apatient background differs between 2 groups; Bstudy population limited to patients finally diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction; and Csmall number of cases. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

The present systematic reviews showed that prehospital administration of aspirin to patients with AMI by non-physician healthcare professionals significantly decreased 30-day and 1-year mortality compared with no prehospital aspirin administration, as did prehospital nitroglycerin administration. The present study suggests that prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals is beneficial in patients with suspected ACS, although the certainty of evidence was very low for both drugs because of the included risk of bias. In the GRADE approach for guideline development, the evidence-to-decision framework clarifies the reasons for determining recommendations, taking into account the favorable and unfavorable effects of an intervention, its costs, and its value for patients. The present systematic reviews provide pieces of evidence that fill the knowledge gaps in the current clinical guidelines.

Early treatment with aspirin has been shown to be beneficial in ACS patients,5 and the administration of aspirin to ACS patients after their arrival at hospital can result in treatment delay. No studies have examined whether prehospital administration of aspirin or nitroglycerin to patients with suspected ACS improves clinical outcomes compared with no administration. In the present study, we were able to conduct a systematic review in retrospective observational studies of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of AMI, in place of those with suspected prehospital ACS. The nitroglycerin analysis was made possible by contacting the authors of a single-center, retrospective observational study reported in 2015,17 identified during the course of searching for evidence for aspirin, and asking for detailed data. The 2010 and 2015 JRC guidelines state that insufficient evidence exists to support or refute the routine administration of aspirin and/or nitroglycerin to patients with suspected ACS in the prehospital setting.8,9 We believe that the present study is the first to provide important evidence to fill the knowledge gaps in these recent guidelines.

There have been concerns about adverse events following prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin. However, the incidence of stroke and major hemorrhage did not differ significantly between the prehospital and in-hospital administration groups in this systematic review. Furthermore, previous studies reported that aspirin was rarely associated with adverse events when administered by prehospital personnel for patients with suspected ACS.18 With regard to nitroglycerin, prehospital administration to patients with suspected ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction did not result in a clinically significant decrease in blood pressure compared with patients who did not receive nitroglycerin.19 Thus, there is little risk of adverse events following a single dose of aspirin and nitroglycerin, and prehospital administration is likely safe. Therefore, early administration in selected patients without contraindications is certainly reasonable.

The prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin has already been implemented in many countries, with both agents having the advantages of being inexpensive and easy to administer by emergency medical service (EMS) personnel to patients with suspected ACS, but prehospital administration has not been approved in Japan. In the future, EMS personnel should be able to administer aspirin and nitroglycerin in the prehospital setting in Japan as well. The 2018 JCS guideline for ACS states that further investigation is needed to confirm the benefit of prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin by EMS personnel.1 As pointed out earlier, there is a knowledge gap in previous guidelines, and it is useful to accumulate evidence regarding the prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin to confirm the safety of these drugs in the prehospital setting before the implementation of prehospital administration by EMS personnel in Japan. We propose the collection of data from patients with and without prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin by physicians attending by rapid response (road and air) medical vehicles. These data may strengthen the certainty of evidence and recommendations in future guidelines. In addition, it would be invaluable for the Medical Control Council to establish an appropriate protocol for prehospital treatment of ACS patients, including a prehospital 12-lead ECG for the appropriate diagnosis of ACS.20

Unfortunately, the present study has several limitations, with the chief limitation being that the certainty of evidence is very low. First our systematic reviews contained no RCTs, and only 3 observational studies for aspirin15–17 and one observational study for nitroglycerin.17 This may be due, in part, to the fact that we only searched the PubMed database and restricted the language to English because of limited resources for this study. Second, the study populations of all included papers consisted of patients who were finally diagnosed with AMI. Third, there were differences in patient characteristics in each observational study, including the frequency of prehospital administration of drugs other than aspirin and nitroglycerin. For these reasons (i.e., the risk of bias, imprecision, and indirectness), the certainty of evidence was downgraded to very low. Although these systematic reviews of studies of the prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin, which had not been previously evaluated, do provide small evidence that will constitute an advancement for the guidelines.

In conclusion, prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin by non-physician healthcare professionals is suggested to be beneficial for patients with suspected ACS, although the certainty of evidence is very low. Further studies are needed to confirm the benefit of prehospital administration of aspirin and nitroglycerin.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Japan Council for Quality Health Care (Minds Tokyo GRADE Center) staff and Dr. Morio Aihara for their help with the GRADE approach. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Rasmus Strandmark (Department of Metabolism and Cardiovascular Research, Institute of Internal Medicine, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Johan Herlitz office, Gothenburg, Sweden) for generously providing us with detailed data not described in his paper.

Sources of Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Japan Resuscitation Council and the Japanese Circulation Society Emergency and Critical Care Committee.

Disclosures

T. Matoba is a member of Circulation Reports’ Editorial Team. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the study design. N.N. and T.Y. identified the studies included in the meta-analysis and analyzed the data. N.N. and T.Y. drafted the manuscript. Y.T., M.K., T. Matoba, and H.N. reviewed the manuscript. All authors were involved in data interpretation and discussion. All authors had full access to all data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Files

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circrep.CR-22-0060

References

- 1.

Kimura K, Kimura T, Ishihara M, Nakagawa Y, Nakao K, Miyauchi K, et al. JCS 2018 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Circ J 2019; 83: 1085–1196.

- 2.

Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE Jr, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR Jr, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 130: e344–e426.

- 3.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting With ST-segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119–177.

- 4.

ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet 1988; 2: 349–360.

- 5.

Freimark D, Matetzky S, Leor J, Boyko V, Barbash IM, Behar S, et al. Timing of aspirin administration as a determinant of survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolysis. Am J Cardiol 2002; 89: 381–385.

- 6.

Bussmann WD, Passek D, Seidel W, Kaltenbach M. Reduction of CK and CK-MB indexes of infarct size by intravenous nitroglycerin. Circulation 1981; 63: 615–622.

- 7.

Jugdutt BI, Warnica JW. Intravenous nitroglycerin therapy to limit myocardial infarct size, expansion, and complications. Effect of timing, dosage, and infarct location. Circulation 1988; 78: 906–919.

- 8.

Japan Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2010. Chapter 5, Acute coronary syndrome, Herusu Shuppan, 2011.

- 9.

Japan Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2015. Chapter 5, Acute coronary syndrome, Igaku-Shoin, 2016.

- 10.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: e1–e34, doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

- 11.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: 1006–1012.

- 12.

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328: 1490.

- 13.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: A new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 380–382.

- 14.

Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods 2006; 11: 193–206.

- 15.

Zijlstra F, Ernst N, de Boer MJ, Nibbering E, Suryapranata H, Hoorntje JC, et al. Influence of prehospital administration of aspirin and heparin on initial patency of the infarct-related artery in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 1733–1737.

- 16.

Barbash I, Freimark D, Gottlieb S, Hod H, Hasin Y, Battler A, et al. Outcome of myocardial infarction in patients treated with aspirin is enhanced by pre-hospital administration. Cardiology 2002; 98: 141–147.

- 17.

Strandmark R, Herlitz J, Axelsson C, Claesson A, Bremer A, Karlsson T, et al. Determinants of pre-hospital pharmacological intervention and its association with outcome in acute myocardial infarction. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2015; 23: 105, doi:10.1186/s13049-015-0188-x.

- 18.

Quan D, LoVecchio F, Clark B, Gallagher JV 3rd. Prehospital use of aspirin rarely is associated with adverse events. Prehosp Disaster Med 2004; 19: 362–365.

- 19.

Bosson N, Isakson B, Morgan JA, Kaji AH, Uner A, Hurley K, et al. Safety and effectiveness of field nitroglycerin in patients with suspected ST elevation myocardial infarction. Prehosp Emerg Care 2019; 23: 603–611.

- 20.

Matsuzawa Y, Kosuge M, Fukui K, Suzuki H, Kimura K. Present and future status of cardiovascular emergency care system in urban areas of Japan: Importance of prehospital 12-lead electrocardiogram. Circ J 2022; 86: 591–599.