2025 年 94 巻 3 号 p. 307-312

2025 年 94 巻 3 号 p. 307-312

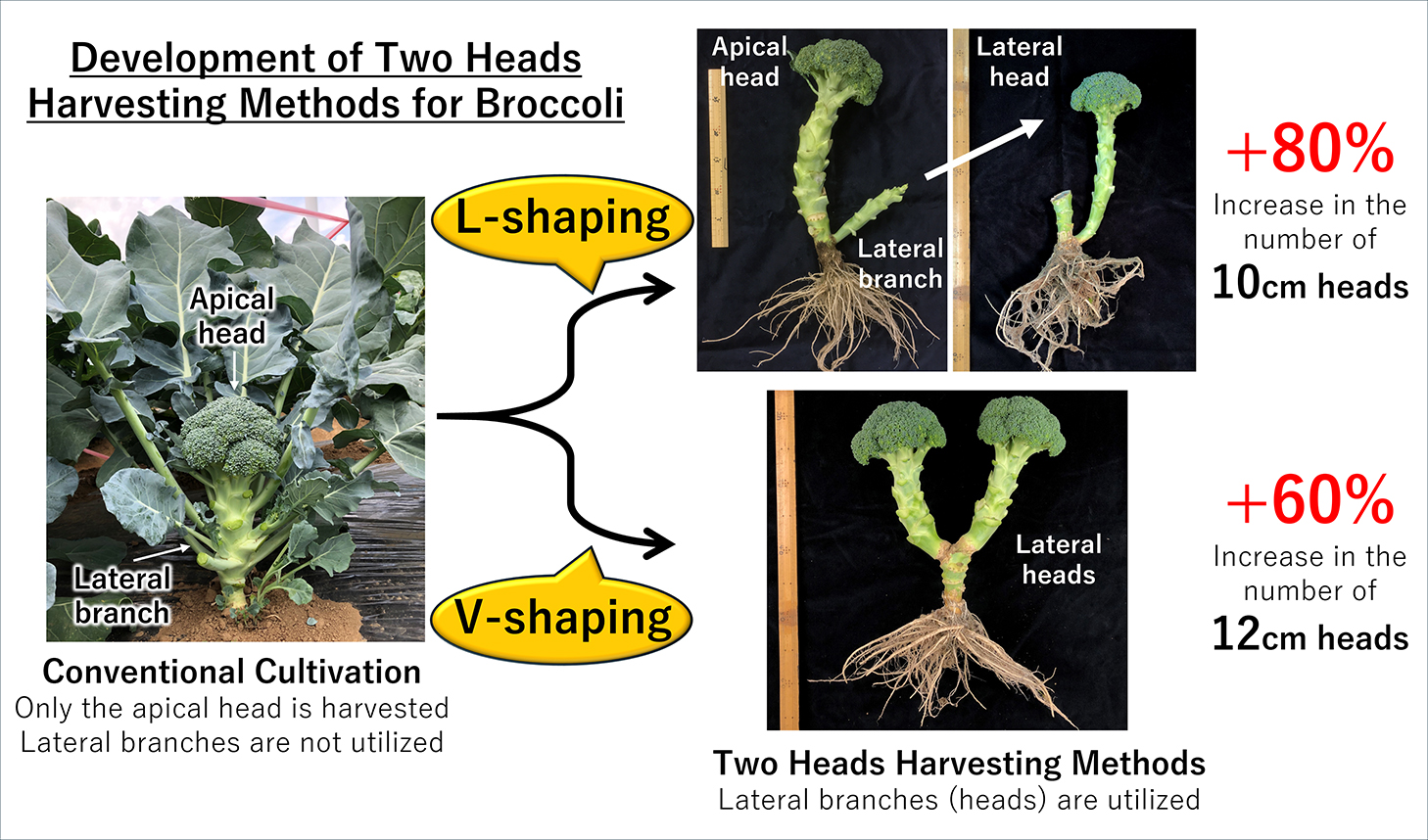

Broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) production and consumption have rapidly increased in Japan, and it is expected to be recognized as a “designated vegetable” by 2026. However, approximately 30% of domestic broccoli for consumption is imported, which means that there is a pressing need to increase domestic production. In Japan, broccoli heads that are harvested and shipped to the market are primarily from the apical bud, with only one head per plant. If the lateral heads from lateral branches (axillary buds) could grow to a marketable size, broccoli production would significantly increase. This study aimed to develop cultivation methods that enable harvesting two heads per plant using lateral branches. By selecting cultivars, investigating the probability of axillary bud generation at each node, and determining the proper timing for decapitation, two cultivation methods were established: “L-shaping” and “V-shaping”. L-shaping is a method that enables the harvest of 10 cm diameter lateral heads after the harvest of a 12 cm diameter apical head in April and May by limiting the number of lateral branches to one or two. This method increased the number of 10 cm heads by approximately 80%, with total yields reaching 17,000 kg per ha. V-shaping enables the harvesting of two 12 cm diameter heads during autumn cropping by pinching the apical bud and limiting the number of lateral branches to two. Pinching at the 7th to 11th leaf stage increased the number of 12 cm heads by approximately 60%, with yields reaching 13,000 kg per ha. Both methods exceeded the national average yield of 10,000 kg per ha, making them highly promising for increasing fresh broccoli production in Japan.

Broccoli is currently classified as one of 35 “specified vegetables” in Japan. However, it has been decided that by 2026, it will be promoted to the 15th “designated vegetable”, a designation considered extremely important to national life. The addition of a newly designated vegetable will be the first in nearly half a century since potatoes were added in 1974, drawing significant attention from the public. Broccoli is sometimes referred to as the “Crown Jewel of Nutrition” due to its rich nutritional content (Elwan and Abd El-Hamed, 2011; Shultz, 2013; Soares et al., 2017). Its popularity has also increased in Japan alongside growing public health consciousness. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications household survey (for two- or more-person households, 2021–2023 average), each household consumes 4,761 g of broccoli annually, amounting to 2,321 yen (MIC, 2024, <https://www.stat.go.jp/data/kakei/>). This represents an approximately 30% increase from 10 years ago (2011–2013 average) when it was 3,674 g (1,693 yen). From 2013 to 2023, the domestic broccoli cultivation area has increased from 13,700 to 17,300 ha, and production has increased from 137,000 to 172,000 t (MAFF, 2024, <https://www.maff.go.jp/index.html>). However, in 2023, Japan still imported 71,000 t of broccoli, mainly as frozen products, highlighting the need for further domestic production (ALIC, 2024, <https://vegetan.alic.go.jp/index.html>).

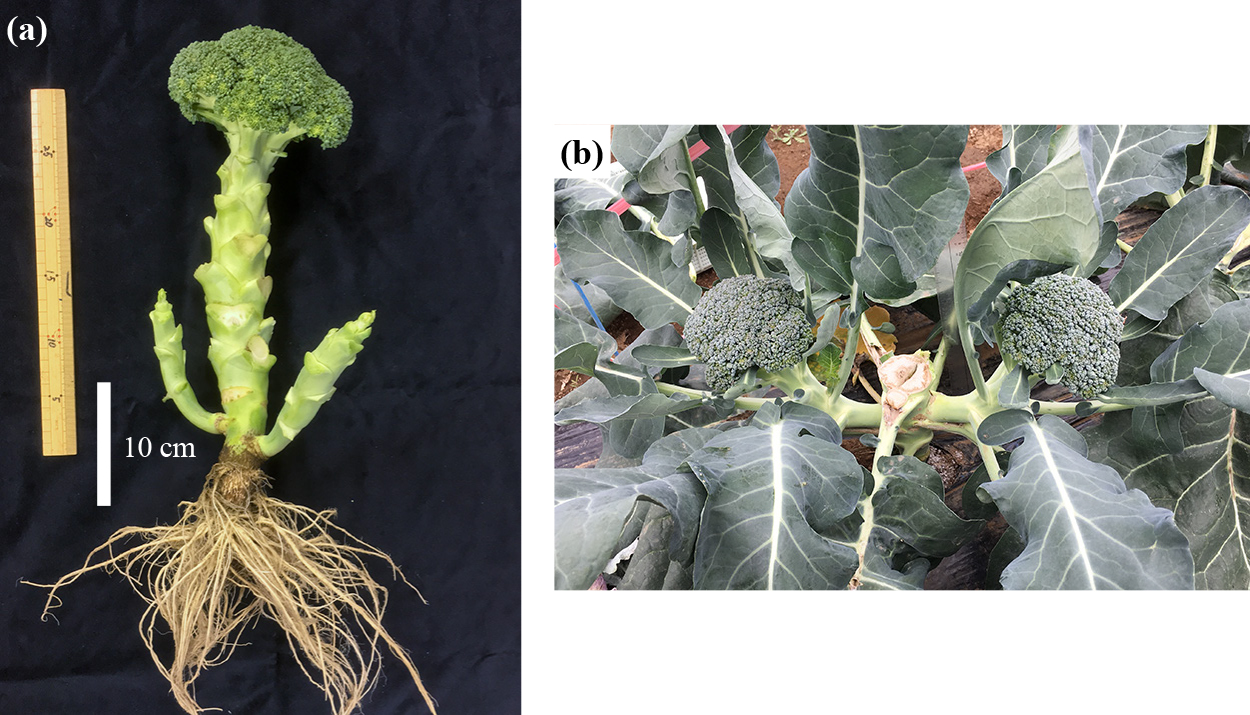

Shipping standards for broccoli vary by region; however, in Japan, broccoli is primarily harvested and shipped for retail and household consumption. For example, in supermarkets in the U. S., the price is often based on weight, such as “$1.5 per pound”, meaning that the sizes of individual broccoli heads do not need to be strictly uniform. However, in Japan, where broccoli is sold at a fixed price per piece (e.g., “¥150 each”), it is essential that each broccoli head is of uniform size when displayed in stores. Therefore, the shipping standard for retail is generally set based on a head diameter centered around 12 cm, with a range of 10–14 cm, classified into M, L, and 2L sizes. Farmers must carefully select broccoli that fits within this size range for harvesting, packaging, and shipping purposes (Fig. 1a, b). Sizes smaller or larger than this range can be considered non-standard products, fetch significantly lower prices, or cannot be shipped to the market.

(a) Broccoli at the time of harvest. To recognize the whole structure easily, some leaves were removed. (b) Broccoli of uniform size packed in a styrofoam container for retail shipment. (c) Small lateral heads packed together and sold at a farmers’ market.

In the field, approximately 30,000 to 50,000 broccoli plants are planted per ha, 70–90% of which are harvested as marketable heads. Each head yields 300–500 g, resulting in a national average yield of approximately 10,000 kg per ha. As the head size is strictly standardized, regardless of whether the amount of fertilizer is increased or the cultivars are changed, the yield per unit area does not significantly increase. Therefore, since 1989, when national statistical data on broccoli became available, the lowest yield recorded was 9,310 kg per ha in 1998, whereas the highest was 10,890 kg per ha in 1989, indicating that the average yield of approximately 10,000 kg per ha has shown no significant increase over the past 35 years. This suggests that it is challenging to increase the yield of standardized broccoli for retail purposes. However, to compete with imported broccoli, which is approximately half the price of domestic broccoli, there is a pressing need to develop innovative technologies that could potentially double the yield. In this context, two head harvesting methods named as “L-shaping” and “V-shaping” have been established. We use lateral branches to enable the harvest of multiple heads from a single plant that meet the shipping standards for retail (Takahashi et al., 2018, 2019; Takahashi, 2020, 2022a, b).

While it is relatively easy to meet the shipping standards for retail with an apical head that develops from the apical bud at the top of the plant shoot, the lateral heads that arise from the lateral buds typically have a maximum diameter of approximately 5 cm and rarely meet the shipping standards. Although these small heads can sometimes be collected and sold at farmers’ markets (Fig. 1c), their low prices relative to the labor involved make them less profitable. However, upon inspection of the broccoli fields near the end of the harvest, it was observed that, albeit infrequently, there were lateral heads that exceeded 10 cm in diameter. As long as the head diameter meets the shipping standard, the origin (apical bud or lateral bud) does not matter. Therefore, if these lateral heads can stably achieve a diameter of 10 cm or greater, the overall yield could significantly increase. This potential is particularly promising during the off-crop season in April and May, which is the transitional period from winter to summer cropping. Therefore, we focused on developing cultivation methods to produce lateral heads that meet retail shipping standards stably.

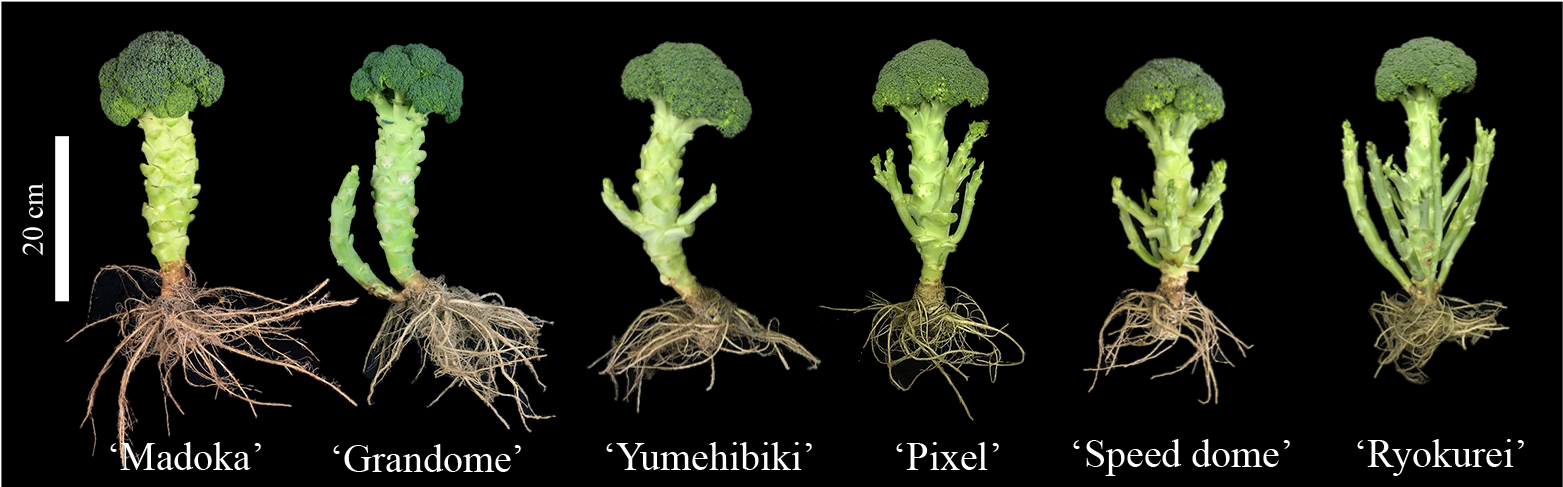

Selection of suitable cultivars and establishing L-shapingPressman et al. (1985) reported that a lower number of lateral branches led to a larger head size. However, Pornsuriya and Teeraskulchon (1997) found that artificially limiting the number of lateral branches did not result in enlargement of the lateral head to a marketable size. Sato (2015) conducted a study in Tokushima Prefecture using the cultivar ‘Grandome’ and implemented winter insulation with non-woven fabric that promoted vigorous growth; this enabled the harvest of apical heads in April and lateral heads in May. When attempting to replicate this method in the Kanto region, it was observed that despite using tunnel covers with superior insulation effects compared to non-woven fabric, ‘Grandome’ occasionally produced a large lateral branch, but generally exhibited unstable development of lateral branches (Fig. 2) (Takahashi and Sasaki, 2019). This method may be limited to warmer regions such as Tokushima Prefecture.

Comparison of cultivar branching characteristics. Leaves were removed for easy shape recognition (The Figure is reproduced from Takahashi and Sasaki (2019) with permission from JSHS).

There is considerable variation among broccoli cultivars regarding the traits of lateral branch development (Fig. 2). Some cultivars produced almost no lateral branches, whereas others produced more than 15 branches from a single plant. Cultivars that do not produce lateral branches are unsuitable for two head harvesting. However, cultivars with excessive lateral branches tend to have thin stems, making it unlikely that large lateral heads will be obtained. Thus, the selection of cultivars with large lateral head development was a crucial first step in this study. Through preliminary tests, it was found that the cultivar ‘Yumehibiki’ (Nanto Seed Co., Ltd., Kashihara, Japan) consistently produced an average of four to five lateral branches per plant, providing a stable number of lateral branches while also bearing relatively large lateral heads. However, if all the developing lateral branches are left intact, many lateral heads become deformed owing to mutual contact before reaching a diameter of 10 cm. To address this, excess lateral branches were removed and only one branch per plant was left, thus avoiding contact with other lateral branches and concentrating photoassimilates in one branch. This was expected to promote further head enlargement. Since the long main stem in a vertical direction and the short lateral branch in a lateral direction took on an “L” shape during this process, we have designated this method as “L-shaping” (Fig. 3a).

(a) L-shaped broccoli at the time of apical head harvesting. To recognize the whole structure easily, all leaves were removed (The Figure is reproduced from Takahashi et al. (2018) with permission from JSHS). (b) A developed lateral head at the time of harvesting. The plants in (a) and (b) are not the same individual, but both cultivars are ‘Yumehibiki’.

After trial and error, it was demonstrated that by L-shaping 7–10 days prior to harvest of the apical head, it was possible to harvest lateral heads of 10 cm in diameter approximately two weeks after the apical head harvest (Fig. 3b). While some lateral heads reached 12 cm in diameter, it was deemed preferable to prioritize the quality (firmness of heads) by harvesting them at a size of 10 cm. By further developing the L-shaping method, three heads were harvested, leaving two lateral branches oriented in opposite directions (Fig. 4). Consequently, the total number of harvested marketable heads increased by approximately 80%. When the yields of seven cultivars that exhibited lateral branch development were compared, ‘Yumehibiki’ and ‘Fighter’ (Brolead Co., Ltd., Tsu, Japan) achieved apical head yields of 11,140 to 11,660 kg per ha, while the lateral head yields ranged from 5,490 to 5,720 kg per ha (Takahashi, 2020). This resulted in a total yield of approximately 17,000 kg per ha, which was approximately 70% higher than the national average yield of 10,000 kg per ha.

(a) The appearance of an L-shaped plant with two lateral branches. To recognize the whole structure easily, all leaves were removed. (b) Two lateral heads at harvest time after the apical head harvest (cut surface in the center). The plants in (a) and (b) are not the same individual, but both cultivars are ‘Yumehibiki’.

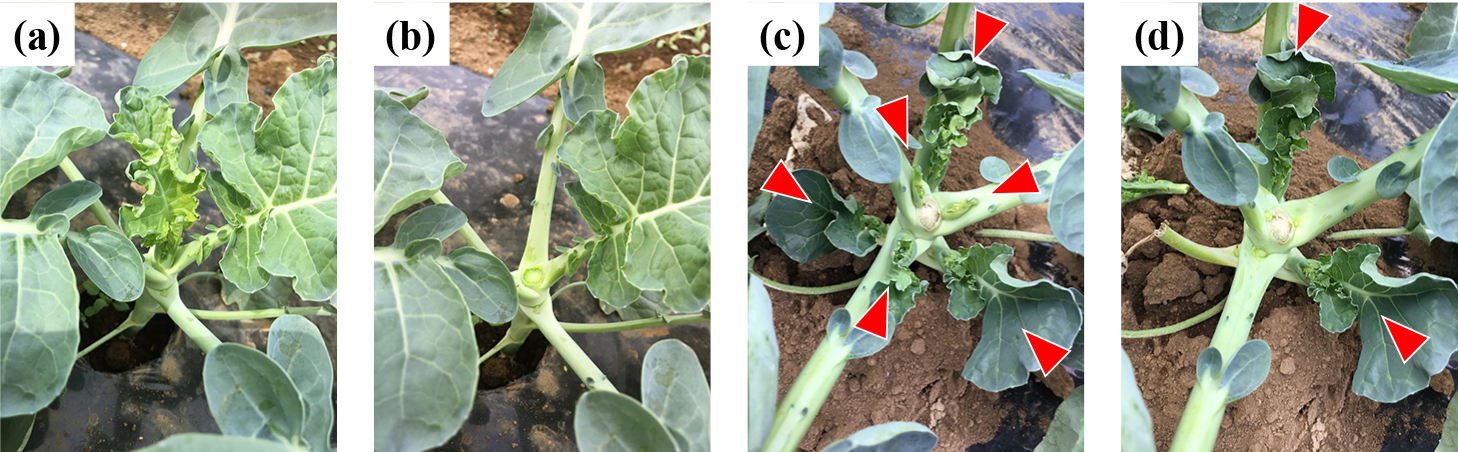

With the L-shaping method, the total number of harvested heads can be increased by approximately 80%; however, the lateral heads typically measure 10 cm. While heads of 10 cm in size are valuable during the off-crop season in April and May, they become a disadvantage in terms of pricing during the autumn and winter seasons when broccoli is abundant. Therefore, we considered the possibility of harvesting two heads measuring 12 cm during autumn and winter. It was thought that as long as the apical bud remained, it would be difficult for the lateral branches to grow. Therefore, the apical bud was pinched off by hand (decapitation), leaving only two lateral branches (Fig. 5). Ultimately, the two lateral branches take on a “V” shape, so this method was designated “V-shaping” (Fig. 6). In fact, this concept has already been reported previously. Kodera (1988) introduced a method in which broccoli plants were pinched at the early seedling stage, specifically between the 2nd and 6th leaf stage, and trained plants with only lateral branches to harvest two or three heads per plant. However, although the plants were grown at a planting density (28,000 plants per ha) lower than the current standard planting density, the head diameter did not always reach 12 cm. Meanwhile, the latest commercial broccoli cultivars have stronger growth potential than those from the 1980s. It was therefore hypothesized that using ‘Yumehibiki’, which is suitable for the L-shaping method, could enable harvesting of two 12 cm heads.

V-shaping Process: (a) Intact broccoli at the 9th leaf stage. (b) Immediately after pinching. (c) Ten days after pinching. The arrowheads indicate elongated lateral branches due to the release from apical dominance. (d) State after removing lateral branches while leaving two vigorous lateral branches growing in opposite directions. The plants in (a) to (d) are the same individual and the cultivar is ‘Yumehibiki’.

V-shaped broccoli at the time of harvest. To recognize the whole structure easily, some leaves were removed. The cultivar is ‘Yumehibiki’.

To determine the optimal timing for pinching of ‘Yumehibiki’, the probability of axillary bud generation (PA) was examined at each node. Lateral buds (early stages of lateral branches) can be classified into axillary buds and adventitious buds based on their origin. However, since most well-developed lateral buds that form lateral heads are developed from axillary buds, analyzing axillary buds was the focus. Therefore, in this review, lateral bud and axillary bud are used almost synonymously. The results showed that while PA was high at the 5th to 8th nodes, ranging from 79–96%, it was only 29–42% at the 3rd, 4th and 9th nodes and less than 13% below the 2nd and above the 10th node, indicating a clear difference depending on the node with a peak at the 5th to 8th nodes. Next, the plants were pinched at the 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, and 15th leaf stages and trained in a V shape. Heads were selectively harvested when they reached 12 cm in diameter, and the number of harvested heads significantly increased compared with that of the control plot, where the conventional method of harvesting a single head was applied, especially when pinched at the 11th leaf stage that resulted in a maximum increase of 61%. However, the stems of lateral branches became thinner compared to the main stem in the control, and the fresh weights of the heads harvested from the V-shaped plots were 263–281 g, 20–30% lower than that of the control plot (362 g), resulting in a total yield of 13,200 kg per ha in the 11th leaf stage V-shaped plot. As previously mentioned, the shipping standard for retail in Japan is primarily based on head diameter, and wholesale buyers have confirmed that heads harvested from V-shaped plots are sufficiently marketable (12 cm). Therefore, the increase in the number of heads harvested from the 11th leaf stage V-shaped plot can be regarded as an approximately 60% increase in marketable yield.

Early pinching makes securing a sufficient number of lateral branches difficult. In contrast, pinching at a late stage led to delayed growth of the lateral branches. In the conventional method, planting at the end of August allowed the apical head to be harvested from late October to November, but pinching at the 9th to 11th leaf stage delayed the harvest by 2–3 weeks, whereas pinching at the 13th to 15th leaf stage caused a delay of 1–2 months. As a result, with pinching from the 13th to 15th leaf stage, the plants were exposed to severe cold before all the heads could be harvested, leading to a decline in quality and yield. The above results demonstrated that the most effective timing for decapitation to maximize yield was around the 10th leaf stage, while protecting the 5th to 8th nodes in the early stage.

The tests up to this point were conducted in experimental fields at NARO, Tsukuba City, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. Subsequent tests in Tsukuba-Mirai City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and Uda City, Nara Prefecture, also showed an increase in the number of marketable 12 cm heads by 69 and 62% using V-shaping, respectively.

Characteristics of the two head harvesting methodsThe time required for V-shaping (pinching and removing excess branches) is estimated to be approximately 100–200 h per ha (Takahashi, 2022a). Considering that the total labor time for one broccoli cultivation cycle is approximately 1,000 h, increasing labor by 10–20% to achieve an approximately 60% increase in yield is appealing. However, it is important to be aware of the potential risks, such as insufficient development of lateral branches or disease emergence from the pinching area, which could reduce yield. Disease occurrence can be prevented by taking precautions, such as pinching on sunny mornings to dry the cut surfaces thoroughly or applying fungicides afterwards. For V-shaping where two heads grow simultaneously, the above-ground part becomes heavy and prone to lodging. Since lodging induces growth delays and soil-borne diseases, hilling more firmly than usual is recommended.

In contrast, although the lateral heads from the L-shaping method were 10 cm in diameter, the L-shaping method allows the apical head to be harvested as usual without the risk of reduced yield. It is important to understand the advantages and disadvantages of both methods and use them appropriately.

In an era where labor-saving methods are increasingly in demand owing to the declining number of agricultural workers, it remains uncertain how well these methods, which involve additional tasks such as pinching and removing excess branches, will be adopted by broccoli farmers. However, both shaping methods can be implemented during the relatively idle period between planting and harvesting; therefore, they are unlikely to become a significant burden. These methods have great potential, particularly in areas where expanding cultivation is difficult, such as urban, coastal, and mountainous regions. Finally, it is hoped that these methods will offer a new perspective on broccoli cultivation, for which yield increases have been stagnant for many years.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Hidekazu Sasaki, my research supervisor at NARO, for his invaluable guidance and support throughout this study. His insights and expertise were instrumental in shaping this research.