2025 年 94 巻 3 号 p. 285-295

2025 年 94 巻 3 号 p. 285-295

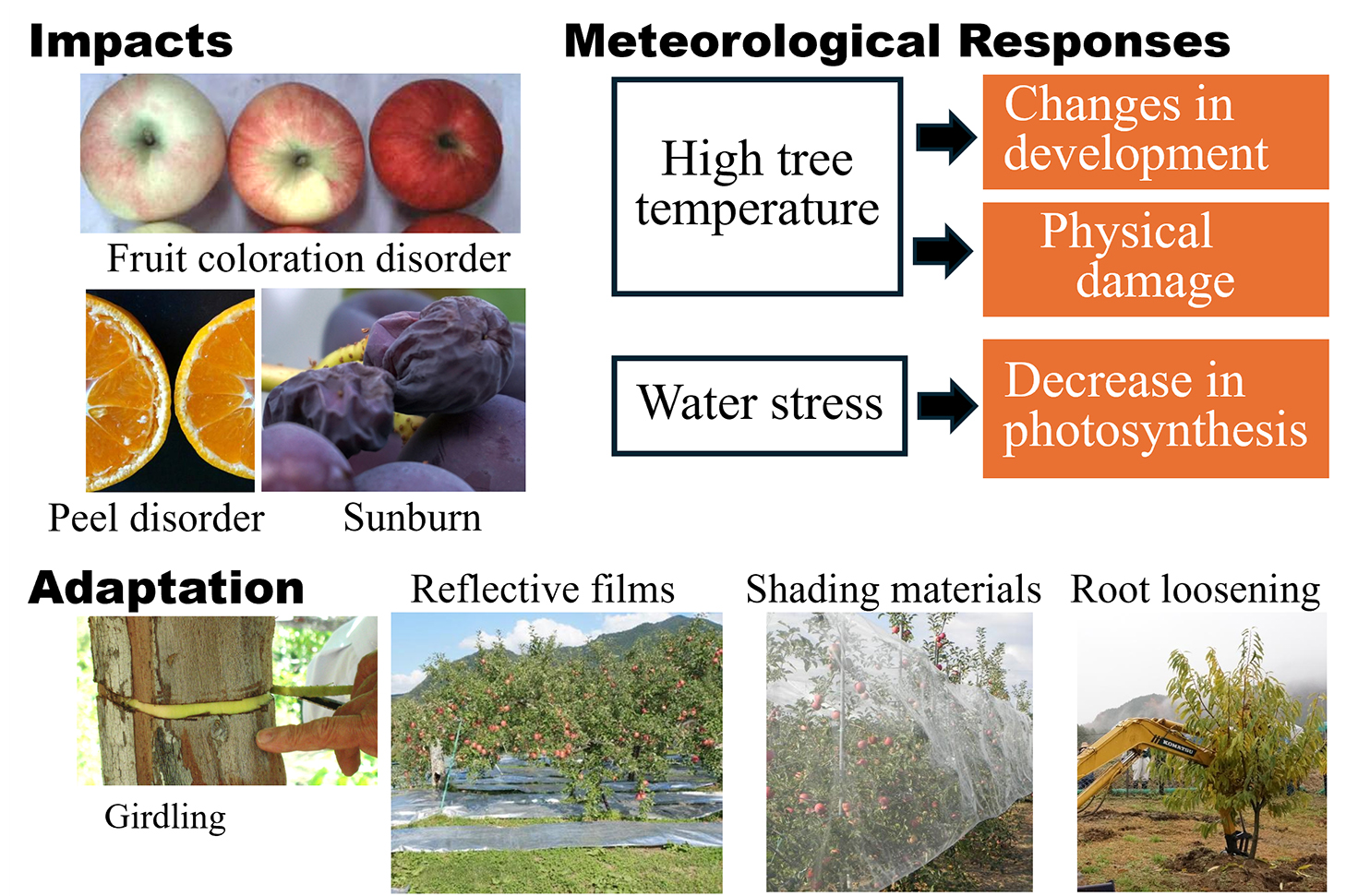

Climate change has affected fruit tree production because meteorological environments determine annual yield, quality, and suitable cultivation locations. This review focuses on the physiological and physical effects of each meteorological element on fruit trees, the impact of climate change on fruit production, and adaptation strategies. The most critical role of temperature is the temporal control of developmental stage changes via developmental rate regulation. Extremely high and low temperatures can cause necrosis of fruit tree tissue, which is a physical effect of heating or freezing. Solar radiation and soil moisture drive quantitative control to determine the size and weight of the entire plant or each part of the fruit tree via photosynthesis. Climate change affects fruit trees through high temperatures and water stress. Temperature rise has altered the development of fruit trees, resulting in earlier flowering, delayed fruit coloration, changes in fruit quality, and increased risk of peel and flesh disorders. Warmer temperatures in autumn and winter delay the release from endodormancy and hardening, as well as accelerating de-hardening, resulting in freezing injuries and flowering disorders. Sunny days with extremely high temperatures cause physical damage to tissues, resulting in sunburn. Water stress reduces the photosynthesis rate, resulting in reduced fruit growth. A lot of research has been conducted on the development of adaptive measures. Adaptation strategies for fruit tree production can be divided into three stages. In Stage 1, short-term adaptation strategies focusing on production techniques include the use of shading materials or reflective films, regulation of development using greenhouses or plant growth regulators, girdling, or shifting the nitrogen fertilization period. Stage 2 involves the use of cultivars that are better adapted to climate change and is a medium-term adaptation strategy because it requires replanting. Stage 3, species or area conversion, is a long-term adaptation strategy. It refers to cultivating fruit tree species that have not been traditionally cultivated in the area or the relocation of cultivation areas. To support this strategy, maps showing future locations suitable for several species have been developed.

Long-term climate change has caused various adverse effects on fruit tree production in long-established production areas (Sugiura et al., 2012) because the meteorological response of crop species is an important factor in determining suitable cultivation locations, as well as annual fruit yield and quality. Climate change is likely to continue, making it difficult to maintain production without implementing countermeasures (i.e., adaptation measures).

Understanding how climate change causes damage is important for efficiently developing adaptation measures and introducing them into production areas. Although the basic meteorological response of fruit trees cultivated in Japan has been studied for a long time, research on the impacts of climate change and adaptation strategies has only really started in the last 20 years, when dramatic future impacts (Sugiura and Yokozawa, 2004) and a lot of the current damage (Sugiura et al., 2007) have been identified. The purpose of this review is to summarize the physiological and physical effects of various meteorological factors on fruit trees, to provide an overview of research on how damage caused by climate change occurs and on adaptation measures.

The effects of meteorological conditions on fruit trees are diverse and complex. Wind and snow exert physical effects on fruit trees such as wind damage (Iizuka, 1961; Konakahara, 1975) and snow damage (Iwakiri, 1982; Kobayashi, 1980). Day length has physiological effects on the rate of shoot growth and flower bud differentiation of satsuma mandarins (Inoue, 1989a) and grapes (Kubota et al., 2001), and humidity may affect them through transpiration and evaporation rates. The most significant factors influencing fruit tree production are air temperature, solar radiation, and precipitation (soil moisture). They act on fruit trees by changing a tree’s temperature, light absorption, and water absorption (Fig. 1). This section outlines the effects of temperature, solar radiation, and soil moisture on fruit trees.

Major physiological and physical effects of the meteorological environment on fruit trees.

Air temperature is the primary determinant of tree temperature, and fruit trees are subjected to both the physiological and physical effects of tree temperature. Deciduous fruit trees use the annual air temperature cycle as a guide to transition between developmental stages including bud differentiation, endodormancy and ecodormancy, budding and flowering, fruit cell division and enlargement, and fruit maturation. Therefore, the most critical physiological effect of temperature is the temporal control of developmental stage changes through regulation of the developmental rate (DVR). The speed and timing of the transition from one stage to the next are primarily controlled by the tree temperature. The relationship between the DVR and temperature forms a bell-shaped curve centered around the peak temperature which varies with the stage (Fig. 1). Other physiological effects of tree temperature include regulation of the balance between vegetative and reproductive growth, respiration rate, and cell division rate. Although the effect of temperature on photosynthesis is small, photosynthesis is reduced due to low winter temperatures.

Extremely high and low temperatures can cause necrosis of fruit tree tissues or even tree death, which is a type of physical damage resulting from heating or freezing. While physiological effects appear based on average temperatures over a period of several weeks, physical effects (damage) occur within several hours.

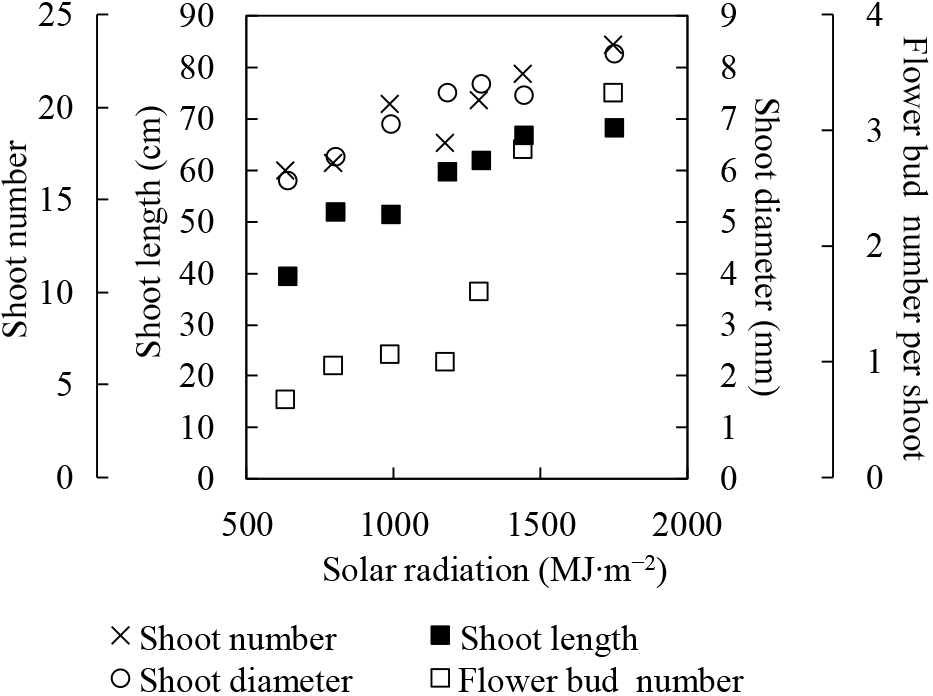

Effects of solar radiation and soil moistureSolar radiation and soil moisture determine the size and weight of an entire plant through their effects on photosynthesis (Fig. 1). Photosynthesis is a chemical process that produces organic matter and oxygen from carbon dioxide, water, and light. Most plant bodies are composed of photosynthetic products and water. Dry matter production drives the quantitative control of shoots (Fig. 2), root growth, fruit growth (Kuroda and Chiba, 2002; Sugiura et al., 1993), sugar content (Kishimoto et al., 1988; Kobayashi et al., 2011), and flower bud number (Ito et al., 2003a; Kuroda and Chiba, 2000). It also affects fruit growth in the following year through reserve nutrients (Sakuma et al., 2000). Drought and soil moisture oversaturation can inhibit water absorption, thereby reducing photosynthesis rates (Shimada et al., 2018). Solar radiation is a major determinant of daily photosynthesis. The photosynthetic rate of the entire tree canopy increases with stronger sunlight as long as the leaf area index (LAI) exceeds a certain value (Ono et al., 1987) because the canopy does not reach light saturation due to leaf overlap. However solar radiation does not exhibit a long-term trend due to climate change.

Relationship between shoot characteristics of ‘Kosui’ Japanese pear and total integrated solar radiation from May to August. Figure reproduced from T. Sugiura et al. (1991a).

Solar radiation and soil moisture control transpiration (Ito et al., 2006). Transpiration and light absorption affect tree temperature. Soil moisture content and getting wet due to rain (Endo and Ogasawara, 1975) influence the water absorption of trees during the fruit maturation period, leading to dilution or concentration of fruit juice (Ito et al., 2003b; Iwasaki et al., 2011; Sakamoto and Okuchi, 1970). Extreme reductions in water absorption can result in leaf wilting, defoliation (Kubo, 1970), and even tree death. Soil moisture also affects hardening (Sakamoto et al., 2015a) and flower bud differentiation (Inoue, 1989b; Ono et al., 2012).

Climate change refers not to year-to-year weather fluctuations, but to long-term trends in meteorological conditions over decades. The annual mean temperature has increased significantly in Japan. Although no statistically significant trends have been observed in annual and seasonal precipitation, the frequency of daily and hourly extreme precipitation has increased, and the frequency of wet days has significantly decreased. These trends are projected to continue until the end of the 21st century (MEXT and JMA, 2020). Because a decrease in the number of wet days leads to soil drying, the key changes in the production environment of fruit trees are rising temperatures and increased drought. This section reviews studies on the changes and damage caused to fruit trees by high temperature or water stress.

Changes in developmental rateIf seasonal air temperatures rise, but the rise is lower than the peak temperature of the developmental rate, fruit tree development is accelerated because the relationship between DVR and temperature forms a bell-shaped curve (Fig. 1). Conversely, if seasonal air temperatures increase from a higher temperature than the peak temperature, fruit tree development is delayed. Because phenology is minimally affected by factors other than temperature, the impact of long-term temperature increase is evident. The DVR of buds for the ecodormancy period increases exponentially with increasing temperature (Sugiura et al., 1991b, 2024a). Observations in orchards have shown that the budbreak and flowering periods have advanced for Japanese pears (Ito and Ichinokiyama, 2005; Toya and Kawase, 2011), apples (Fujisawa and Kobayashi, 2010; Sugiura et al., 2013), grapes (Kamimori et al., 2019), peaches (Adachi et al., 2018), and Japanese apricots (Shimizu and Omasa, 2010). High temperatures during the young fruit period (cell division period) accelerate fruit development (Hayama et al., 2007; Kadowaki et al., 2011; Sikhandakasmita et al., 2022; Sugiura et al., 1995), which decreases the number of fruit development days (days from flowering to ripening or harvest).

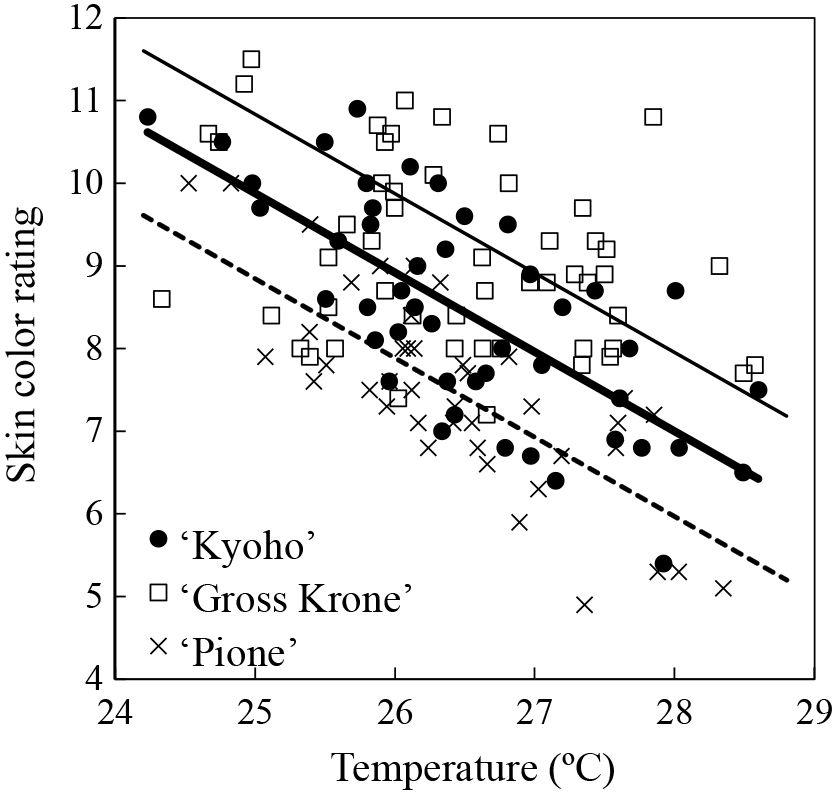

During the summer and autumn seasons, many days exhibit temperatures exceeding the peak temperature of the developmental rate; as a result, the rise in air temperature during the fruit maturation period tends to inhibit skin coloration development in apples (Honda and Moriya, 2018; Sugiura et al., 2023a), persimmons (Niikawa et al., 2014), and citrus (Sato and Ikoma, 2020; Takagi et al., 1994). For example, a few reports (Sugiura et al., 2018, 2019a) suggested that an increase of 1°C in the mean temperature during the maturation period, after the veraison period, of grape cultivars resulted in a decrease of approximately 1 unit on the color chart (Yamazaki and Suzuki, 1980) of the skin color at harvest (Fig. 3). Experiments with artificial temperature treatments have shown that grape berries cannot develop coloration at temperatures that are too low (Kobayashi et al., 1965), and the diurnal temperature range has little effect on coloration (Kurihara, 1973).

Relationship between the grape skin color rating based on a color chart at harvest and the mean air temperature 43 days from 50 DAF (days after full flowering) for ‘Kyoho’ and ‘Gross Krone’ and 46 days from 46 DAF for ‘Pione’. Linear regression for ‘Kyoho’ (bold line; y = −0.96x + 33.9) at air temperatures ≥ 24°C are shown. Linear regressions at air temperatures ≥ 24°C for ‘Pione’ (dashed line; y = −0.96x + 32.8) and ‘Gross Krone’ (thin line; y = −0.96x + 34.8) are based on the assumptions that their regression slopes were equal to that for ‘Kyoho’.

High temperatures during the maturation period also delay starch disappearance and water-core development in apples (Sugiura et al., 2023a). Conversely, high temperatures during the maturation period accelerate acid reduction in fruits such as apples, grapes, and pineapples (Sugiura et al., 2020, 2023a, b); however, this is not a result of accelerated fruit maturation, but rather due to an increase in the respiration rate. The inhibition of skin coloration can delay the harvest of some tree species (Adachi et al., 2018). If early flowering and delayed harvest occur simultaneously, the number of days required for fruit development increases. At harvest, this decreases acid content, fruit firmness, and storability, or increases sugar content, fruit size, and the risk of peel and flesh disorders, such as peel puffing in citrus and water-core in Japanese pears (Ito, 2020; Sakuma et al., 1995; Sato and Ikoma, 2020; Sugiura et al., 2007, 2013).

Since the peak temperature of the developmental rate in the endodormancy period is low, at around 6°C for persimmon, Japanese pear, sweet cherry, peach, and apple (Sugimura et al., 2006; Sugiura and Honjo, 1997a, b, Sugiura et al., 2006, 2010, 2024a), any temperature rise in autumn or winter delays the release from endodormancy (Honjo, 2007; Tominaga et al., 2022) and leads to flowering disorders in heated greenhouse cultivation (Tominaga et al., 2019). In the open field, because the flowering period of cultivars with lower chilling requirements tends to be earlier than that of cultivars with higher chilling requirements in warm winters, even among cultivars that flower at similar periods in a normal winter, the flowering periods do not coincide, and cross-pollination is disrupted (Ito, 2020; Kitamura et al., 2024).

Freeze injury causes flowering disorders in Japanese pears (Ito et al., 2018; Tominaga et al., 2022) and mortality in chestnuts and peaches. Although the direct cause of freezing injury is physical damage to plant tissues due to intracellular freezing, the risk of freeze injury increases with delayed hardening or accelerated de-hardening caused by warm autumns or winters (Kang et al., 1998; Miyamoto et al., 2016; Mizuta et al., 2024). When flowering occurs earlier, owing to high temperatures in the spring, the risk of frost injury increases as the flowering period overlaps with the frost period (Asakura et al., 2011). Additionally, low temperatures during the flowering period can inhibit pollen germination (Kuroki et al., 2017).

Physical damage caused by high temperaturesThe surface temperature in parts of fruit exposed to direct sunlight under high air temperature can reach approximately 50°C, causing sunburn to occur (Fukuda et al., 2019). The maximum temperatures of fruit surfaces facing south to west, which are exposed to the afternoon sun, are higher than those of fruits facing north (Chikaizumi, 2007), and those of larger fruits are higher than those of smaller fruits (Konno and Sugiura, 2024). Stomatal closure of leaves and fruits due to water stress reduces transpiration and prevents the release of vaporization latent heat, causing tree and fruit temperatures to rise. Therefore, sunburn increases under water stress conditions (Kanetsune et al., 2020).

Other effects of high temperature or water stressDepending on the tree species and conditions, other effects of high temperature may occur. Fruit trees generally undergo vegetative and reproductive growth simultaneously and high temperatures tend to shift the balance toward vegetative growth. This can result in excessive (Makino et al., 1986) or secondary shoot growth, delayed or inhibited flower bud formation (Inoue, 1989b), physiological fruit drop (Sato et al., 2010), and reduced fruit growth or sugar content.

Cell division rates in fruits (Tamura et al., 1981) and roots (Fukui et al., 1994) increase with high temperatures during the cell division period. Physiological fruit drop can also occur due to nutrient competition among fruits, which is facilitated by accelerated cell division in each fruit. However, the higher the temperature, the earlier the cessation of fruit cell division occurs, and no temperature-dependent difference is observed in the number of fruit cells at harvest (Sugiura, 1997). Changes in the production environment due to temperature rises, such as changes in pests (Konno and Sugiura, 2023), diseases, or weed activity, higher storage room temperatures, and increased inorganic nitrogen levels in the soil (Inoue, 2018), indirectly affect fruit tree production.

Water stress reduces photosynthesis and transpiration rates due to stomatal closure (Ito and Ishida, 2023; Tsuchida and Yakushiji, 2017). Reduced transpiration is one of the causes of sunburn and reduced photosynthesis leads to decreased shoot growth (Teng et al., 1999) and fruit growth (Morinaga, 1993).

However, because low temperatures become the limiting factor for photosynthesis in winter for evergreen fruit trees (Konno and Sugiura, 2017; Morinaga, 1993), an increase in winter temperatures enhances tree vigor and increases the number of flower buds and fruit yield.

Measures to prevent damage caused by climate change or to utilize its benefits are referred to as adaptation strategies. Fruit tree adaptation strategies can be divided into three stages (Sugiura, 2019). The first stage (Stage 1) is adaptation through production techniques, i.e. improving cultivation methods while maintaining the current trees. This stage consists of short-term adaptation strategies including methods to avoid high temperatures and increase high-temperature tolerance. Stage 2 is the use of cultivars that are better adapted to climate change and is a medium-term adaptation strategy because it requires replanting. Stage 3, species or area conversion, refers to the cultivation of tree species that have not been traditionally cultivated in an area, or the relocation of cultivation areas. While this approach is highly effective, it is the most time-consuming adaptation strategy as there are several barriers to its implementation.

Stage 1: Improving cultivation methodsFruit damage caused by high temperatures in summer and autumn can be mitigated by lowering the temperature of trees or fruits. One method for reducing fruit temperature is to limit the amount of fruit exposed to sunlight. Methods to prevent sunburn include using shading materials, such as shade nets (Takeuchi et al., 2001) or fruit bags with high shielding performance (Fujii et al., 2021), and having numerous shoots that avoid direct sunlight. Citrus fruit thinning in which all fruits are removed from the top (Takagi et al., 2009) or surface (Kitazono et al., 2009) of a tree, is an effective method for reducing sunburn and peel puffing.

For fruit species in which skin color develops before mid-summer, skin coloration can be improved by greenhouse cultivation, which advances the flowering period and shifts the maturation period to a cooler season (Sugiura et al., 2019b). Conversely, the flowering and harvest periods can be delayed by covering the trees with a reflective film until the flowering period (Honjo et al., 2005) or using secondary induced shoots that germinate after removing the current shoot, flower clusters, and growing lateral shoots (Kishimoto et al., 2022). Because the cooling effect of evaporative heat loss is diminished due to stomatal closure in leaves and fruits caused by water stress, preventing soil drying during periods of sunburn risk is important (Kanetsune et al., 2020). Spraying water from the top of trees can reduce sunburn by effectively reducing tree temperatures (Kudo et al., 2017).

Plant growth regulators that correct developmental stage shifts can be used to increase high-temperature tolerance. The combined spraying of gibberellin and prohydrojasmon suppresses the development of satsuma mandarin fruits and reduces peel puffing (Sato et al., 2015; Yamaga and Makita, 2023). Abscisic acid (ABA) accelerates grape skin coloration (Sugiura et al., 2019c). Cyanamide accelerates endodormancy release (Yoshikawa et al., 2014) and prevents flowering disorders in heated greenhouses. Skin pigments, such as anthocyanins in apples and grapes and carotenoids in persimmons, increase when exposed to light (Arakawa et al., 1985; Honda and Moriya, 2018). Covering the ground with reflective films enhances skin coloration of apples (Fujisawa and Moriya, 2010) and persimmons (Matsumoto et al., 2021). Because fruits covered by leaves produce little pigment, removing the leaves covering fruit improves apple coloration (Iwanami et al., 2016). When fruits contain an abundance of photosynthates, anthocyanin synthesis becomes easier, even at high temperatures, leading to improved skin coloration. One method to increase the photosynthates in each fruit is to reduce the number of fruits per tree (thinning). Fruit thinning is particularly effective in grapes, although it sacrifices yield (Yamane and Shibayama, 2006). Treatments such as girdling (Harima et al., 2006; Koshita et al., 2011; Yamane and Shibayama, 2006) and strapping (Hasegawa and Nakajima, 1991), which redirect the photosynthates normally distributed to the roots towards the fruit, enhance skin coloration without reducing the number of fruits.

Because application of nitrogen fertilizer in autumn or winter reduces freezing resistance, shifting the application period from autumn or winter to spring can reduce flowering disorders in Japanese pears (Koshigae et al., 2022; Matsumoto et al., 2010; Sakamoto et al., 2017) and mortality in chestnuts (Inoue et al., 2019; Sakamoto et al., 2015b). Branches with a high moisture content are more susceptible to freezing injury (Horimoto and Araki, 1999a), so treatments such as soil moisture reduction (Mizuta et al., 2022; Sakamoto et al., 2015a) and root loosening (root pruning) can reduce freezing injury (Horimoto and Araki, 1999b; Mizuta et al., 2021). Peach (Kamio et al., 2006; Miyamoto et al., 2011) and chestnut (Mizuta et al., 2023) rootstocks with high freezing resistance, loquat cultivars with high cold resistance (Sugiura et al., 2016), and pollinizer cultivars of Japanese pears with pollen having higher germination properties at low temperatures (Shibasaki et al., 2023; Takemura et al., 2022) have been selected.

Stage 2: Selecting cultivars for adaptation to climate changeBecause fruit trees are only replanted approximately every 30 years, introducing new cultivars into commercial fruit orchards is not easy. However, adaptation strategies using production techniques (Stage 1) incur additional costs and effort annually. Therefore, some cultivars have been used to adapt to climate change. For example, bud mutations of the major apple cultivars ‘Fuji’ (Komatsu, 1998) and ‘Tsugaru’ (Kon et al., 1994) that develop colored skins more easily than the parent cultivars have been selected.

Recently, new hybrid cultivars adapted to warming have been developed, including the Japanese pear ‘Rinka’, which is a cultivar resistant to flowering disorder (Saito et al., 2020). Superior-colored cultivars of apples such as ‘Kinshu’ and ‘Beniminori’ (Abe et al., 2023a, b) and of grapes such as ‘Queen Nina’ and ‘Gross Krone’ (Sato et al., 2013, 2021) have been developed. Yellow cultivars such as ‘Morinokagayaki’ apple (Abe et al., 2016) and ‘Shine muscat’ grape (Yamada et al., 2017) have no issues with skin coloration. Japanese peach cultivars require long chilling periods for endodormancy release; however, the ‘Sakuhime’ peach (Sawamura et al., 2017), developed by crossing Japanese cultivars with a Brazilian cultivar with low chilling requirements, has a low risk of flowering disorder in heated greenhouses. ‘Harehime’ (Yoshida et al., 2005) and ‘Mihaya’, hybrids between satsuma mandarin cultivars and an orange cultivar that is resistant to peel puffing and is harvested after January (Yoshida, 2003), can be harvested by December and are resistant to peel puffing.

Stage 3: Species or area conversionSince fruit trees are vulnerable to the effects of climate change, it is possible that the suitable locations for fruit tree cultivation will move northward. The fruit tree species cultivated in Japan can be classified into four groups based on their botanical characteristics and temperature suitability. In order of suitability for cold climates, they are called cold-region deciduous fruit trees, temperate deciduous fruit trees, temperate evergreen fruit trees, and subtropical/tropical fruit trees. Replacing cold-region deciduous fruit trees, such as apples and cherries, with temperate deciduous fruit trees, such as Japanese pears and peaches, or replacing temperate evergreen fruit trees, such as satsuma mandarins, with subtropical fruit trees, such as avocados, can be expected to have significant adaptive effects. However, tree species conversion is challenging for individual producers to undertake alone and requires a long-term strategy for the entire production area involving the creation of new regional brands or cooperation with local governments.

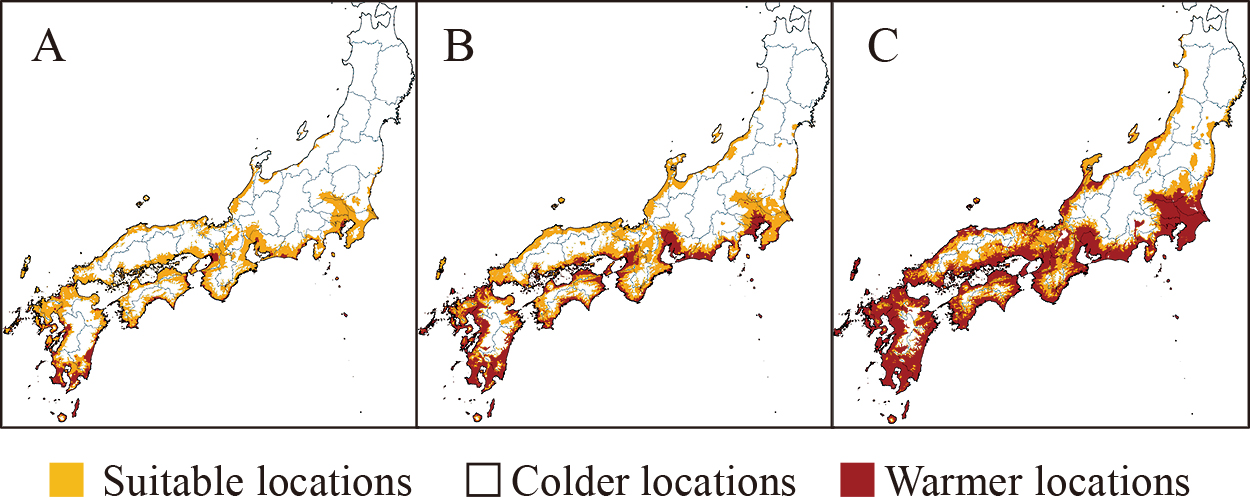

To support producers and local governments in developing long-term production strategies, predictive maps showing future locations suitable for apples, satsuma mandarins (Fig. 4), wine grapes, and subtropical fruits such as tankan and avocado (Inoue and Kominami, 2023; Nemoto et al., 2016; Sugiura and Yokozawa, 2004; Sugiura et al., 2014, 2024b) have been developed. Among the suitable locations for satsuma mandarins currently, the percentage that remained suitable at the end of the 21st century varied in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, ranging from 0% in a very high emission scenario to approximately 80% in a low emission scenario. This indicates the substantial impact of climate change mitigation measures on the current satsuma mandarin production areas. Adaptation maps have also been developed. Although regions with a high frequency of poor skin coloration in grapes may spread to the plains of most areas, except northern Japan, by the mid-21st century, adaptive measures such as greenhouse cultivation and superior-colored cultivars are estimated to greatly reduce the number of these regions (Sugiura et al., 2019b). In fact, the replanting of new tree species is progressing gradually. In recent years, peaches (Fujisawa and Kobayashi, 2013) or wine grapes (Hirota et al., 2017) have been planted in apple-producing areas of the northern Tohoku region or Hokkaido and subtropical fruit tree species such as blood oranges have been planted in temperate evergreen fruit tree-producing areas.

Locations estimated as suitable for satsuma mandarin cultivation in Japan for 2080–2099 under projected temperatures based on MRI-ESM2-0 under SSP1-RCP2.6 (A, low emissions scenario), SSP2-RCP4.5 (B), and SSP5-RCP8.5 (C, high emissions scenario). Figure reproduced from Sugiura et al. (2024b).