2022 年 10 巻 2 号 p. 168-178

2022 年 10 巻 2 号 p. 168-178

Mega-events have been explored by cities for urban reimaging and urban transformation processes. Due to their scale and catalytic effects, mega-events offer great opportunities for cities to showcase their local culture and create opportunities for their local economy, as well as the tourism and retail sectors, while also serving as catalysts for urban regeneration. The current COVID-19 pandemic has created a global crisis of unprecedented scale. Several extreme measures have been deployed to avoid contagion risk, including city lockdowns, subjecting residents to COVID-19 quarantine and social distancing, the closure of tourism attractions and the retail sector, as well as travel restrictions. This global crisis created a temporary shock to large-scale travel, the tourism sector and mass gathering, which resulted in the cancellation or postponement of nearly all mega-events in 2020. This paper identified the various challenges faced by event organisers during the COVID-19 pandemic and examined how relevant stakeholders addressed event risks and uncertainties. This paper suggests the incorporation of resilience in strategies for event legacy creation. Mega-events must incorporate adaptability and flexibility in their design, as well as event legacy planning and capacity building, to address the vulnerability and disturbances that future mega-events may encounter.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has created a significant threat to global population health. In the 22 months since the SARS-COV-2 coronavirus was discovered, the world has seen approximately 240 million cases and nearly 5 million deaths (World Health Organization (WHO) 2020c). Many countries have imposed lockdowns to restrict the liberty and movement of people with the hope of preventing the virus from spreading. Besides detecting, isolating and treating cases of infection, corresponding measures were taken to curb mass population flow and gatherings, such as working from home, social distancing and inbound travel restrictions. Therefore, beyond interruptions to people's daily lives, the COVID-19 pandemic is having drastic consequences on the tourism and retail sectors. For cities that plan to host mega-events, massive challenges have arisen.

Since large-scale gatherings have been banned in almost all countries that have encountered COVID-19 transmission, nearly all mega or minor events at the global, national or local level have been cancelled or postponed. Currently, no one can predict when such mega-events can resume. The cancellation or postponement of events can significantly affect event planning and the short-term financial impact of mega-sports events. Beyond these events, the future of mega-events and the long-term effects of event-led strategies for urban transformation are at a crossroads. This sheds doubt on whether cities can still pursue the strategy of event-led development in the future. In the post-pandemic era, what measures should be taken to ensure that events are pandemic proof? For cities’ long-term development, which direction should event-led strategies take?

This paper explores the relationship between mega-events and sustainable development through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, this paper attempts to identify the challenges event organisers face during the COVID-19 pandemic and how these have been addressed. On the other hand, this paper also discusses how future mega-events should address spatial, economic and social challenges to become resilient in the post-pandemic era. The paper is based on a study of mega-events between March 2020 and June 2021. The author studied extensive literature on mega-event and event legacy studies. Moreover, the author investigated various policy documents regarding the COVID-19 pandemic at different institutional levels in different countries worldwide. The author also conducted interviews (e.g., the Floriade) to gain first-hand information on event policies, pandemic risks from the perspectives of event organisers and how corresponding risk mitigation measures were established.

The paper is divided into five sections. Following the introduction section, the following section examines the issues host cities had to deal with in hosting events and legacy creation before the pandemic. Section 3 examines challenges that arose during the pandemic and how event organisers have coped with the contagion risk to continue hosting mega-events, including risk assessment and risk mitigation measures. Section 4 discusses a resilient path for mega-events in the post-pandemic era. Event legacy strategies should incorporate short- and long-term adaptability strategies. Section 5 summarises the research findings and advocates for mega-event planning to begin with a long-term perspective and improve the resilience of future mega-events.

Mega-events are described as ‘large events of world importance and high profile which have a major impact on the image of the host city’ (Bramwell, 1997). For host cities, the role of mega-events as catalysts for urban development has been recognised in recent years. Previous studies noted that mega-events can trigger the erection of event buildings, new infrastructure and improved urban space (Chalkley & Essex, 1999; Chen, Qu, & Spaans, 2013; Gold & Gold, 2008). The consideration of post-event impacts is drawing increasing attention because the scale of mega-events has increased dramatically in recent decades. For example, the Summer Olympic Games in 2012 had to accommodate nearly 11000 athletes and 300 events, not to mention thousands of spectators, journalists, coaches, officials, volunteers and Olympic community members (International Olympic Committee (IOC) 2012). The increasing number of events, visitors, journalists and event community members has resulted in host cities having to address the rapid growth in spatial and logistic requests. Consequently, host cities must address four event-related functions in their preparations: 1) Sporting stadiums/cultural venues/training facilities/temporary facilities; 2) Communications/security facilities; 3) Transport infrastructure/public spaces; 4) Tourism and retail amenities (Davidson & McNeill, 2011; Smith & McGillivray, 2020). As the scale of mega-events expands, these events substantially influence spatial development, economic growth and social development. Correspondingly, sophisticated event management becomes crucial in event planning, finance, logistics, risk management, marketing in pre-event preparation, event operations and event site management in the post-pandemic era.

In recent years, legacy research has become an essential part of mega-event studies. The term ‘legacy’ was defined as any net impact arising from a mega-event, which includes positive or negative changes in addition to transformation (Brimicombe, 2015; Gold & Gold, 2007). Research on legacy should examine any outcomes that affect people and/or space caused by structural changes that stem from the Olympic Games (Preuss, 2019). Preuss (2007) suggested examining legacy by looking at space, time, the tangible/intangible, the positive/negative and the planned/unplanned. Leopkey and Parent (2012) further noted that the definition of legacy evolved from the benefits and impacts of the events to sustainable long-term legacies, which have been strategically planned from the time of the bid after mapping and contextualising the evolution of the concept of legacy over time. Preuss (2019) stressed the value of consequences from the structural changes that mega-events create, which are bound to a territory. This research shows that legacy has many aspects and dimensions, ranging from the more commonly recognised aspects—i.e., architecture, urban planning, city marketing, sports infrastructure, economic and tourist development—to others that are just as (if not more) important but less recognised (IOC, 2018). Various topics, such as sustainability, culture, value and equity, are included in legacy studies. In recent years, the increasing recognition of social legacy has allowed local communities to have a fair chance to benefit from mega-events.

In earlier years, mega-events were held in temporary urban spaces or wastelands after clearance. These event sites were largely settled on green fields that were later used for more complex spatial requests. In recent decades, mega-events ‘seem to hold the potential and the capacity to achieve the necessary transformation’ in host cities—especially those with declining economies or deteriorating urban spaces (Roult & Lefebvre, 2013). Gold and Gold (2020) further consolidated the links between remediating land for Olympic event spaces and pursuing a legacy. Chen (2015) examined how host cities have explored the Summer Olympic Games for urban transformation. They either reused existing venues or developed post-event functions for venues. Moreover, host cities attempt to integrate their venues and Olympic village with their urban regeneration plans to develop new urban functions for the event sites. The third strategy is to integrate the Olympic plans with the master plans of host cities (e.g., the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games). Some host cities start with the legacy plan and then identify permanent and temporary elements to accommodate the event requirements (e.g., the 2012 London Olympic Games).

Despite an increasing number of studies on legacy and experiences in legacy planning, host cities have encountered various obstacles to creating a positive event legacy. First, most event host cities struggled with the post-Games use of event venues. Since event venues are designed to address the spectator capacity demands of Olympic events, these venues can rarely find a comparable sport in terms of spectator numbers for post-event use. Even with careful consideration of post-event use, the venues for the Olympic Games in Sydney, Beijing and London have difficulty finding permanent tenants, which highlights the need to stress the mixed functions of Olympic venues to achieve a high degree of commercialisation. Second, certain events have strict spatial and accessibility requirements, making spatial claims challenging for host cities to develop post-event uses for citizens besides local sporting events. For example, the IOC holds the ‘One Games-One City’ principle for the applications of host cities, with the event number increasing to 300. As a result, it is challenging to reuse event-related facilities in the post-event period. Third, host cities usually face tight schedules to prepare the event as it grows in scale and complexity. Since host cities need to mobilise massive investment and construction within a tight schedule of seven years, many considerations on legacy creation fall short. Cost overrun is often a headache for host cities. Moreover, host cities tend to prioritise investments in constructing event venues and infrastructure instead of other social investments. Moreover, pressure related to the global image of a host city may result in host cities mainly addressing issues related to event organisation. In this regard, more ambitious goals related to sustainability or social inclusion might be compromised.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a humanitarian crisis that affects many lives and has created a global crisis of unprecedented scale. Many extreme measures have been deployed to avoid contagion risk, including city lockdowns and residents being subject to COVID-19 quarantine, social distancing, restrictions on mass gatherings, the temporary closure of tourism attractions, event venues and the retail sector, as well as international travel restrictions. As a result, this global crisis created a temporary shock to large-scale travel, the tourism sector and mass gatherings (Mohanty, Dhoundiyal, & Choudhury, 2020). The pandemic has also resulted in the cancellation or postponement of nearly all mega-events in 2020, including the Summer Olympic Games, the World Expo and the World Cup (Table 1). Although some events resumed, they prohibited audiences or sports fans from joining the events due to the fear of outbreaks.

Table 1. Policy on restrictions for some key mega-events during the COVID-19 pandemic (summarised by the author) (Destination(S) Europe, 2021; Eurovision Song Contest, 2021; Expo 2020 Dubai, 2021; Floriade, 2021; IOC, 2021)

| Host cities | Mega-events | Impact of the Pandemic | Key mitigation measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tokyo, Japan | Summer Olympic Games 2020 | Postponement to July 2021 | No international guests for events |

| Dubai, United Arab Emirates | World Expo 2020 | Postponement to 1 October 2021–31 March 2022 | Remote working policy; social distancing; cancelling of business travel; installation of thermal cameras; intensification of all sanitation procedures and hand sanitiser units |

| Almere, The Netherlands | Floriade | Postponement to July 2022 | Scaling down; social distancing; crowd control |

| Novi Sad, Serbia; Timisoara and Elefsina, Greece | European Capitals of Culture | Novi Sad postponed from 2021 to 2022, Timisoara and Elefsina from 2022 to 2023 | Programme adjustments |

| Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Eurovision Song Contest | Postponement from 2020 to 2021 | Limited spectators (20% capacity); delegates stay in a bubble; crowd control |

According to the WHO Mass Gatherings Risk Assessment COVID-19 Tool, hosting events during the pandemic's active phase was considered very high risk (WHO, 2020a, 2020b, 2020d). The WHO suggests three pillars for the Mass Gathering Risk Management Tool, including risk evaluation, risk mitigation and communication. Following this guidance, event organisers need to assess a series of factors. These include the current stage of the local outbreak and known transmission dynamics, its geographic distribution, the number of participants and their risk profiles before using the risk assessment tool to assess risks, and the effectiveness of current and proposed mitigation measures. For the risk assessment of a specific event, event organisers must consider the type of event, its scale and the type of space that can accommodate physical distancing. There are many policy documents and protocols developed by national and local governments to guide risk assessments by event organisers. Table 2 shows the risk assessment model developed by Event Flanders (2021). Notably, this protocol follows the instructions of the WHO on risk assessment tools. Moreover, it was developed to be more applicable to big and small events for their own national and local context. The parameters listed in Table 2 allow event organisers to tailor their risks according to the specific features of events.

Table 2. Key risks identified by the COVID event risk model: An example from Flanders, Belgium (Event Flanders, 2021)

| Risk elements | Go | No-go/Go-with advice |

|---|---|---|

| COVID coordinator | Installing of COVID coordinator | No installing of COVID coordinator |

| Outdoor/ventilation | Outdoor; indoor with approved ventilation | Indoor without an approved ventilation |

| Event dynamic |

Stand still; Controlled movement with guaranteed social distancing; |

Uncontrollable crowd; seat arrangement not according to regulations |

| Density/capacity/ face masks | Respect the rules of social distancing | Space for visitors/people present not according to the rules |

| Capacity used | Possible capacity not fully used | Maximum capacity exceeded multiple times |

| Vulnerable groups | The event is not for vulnerable groups | The event involves a vulnerable group |

| Local focus (international public) | No focus on the international audience (international attendees less than 30%) | Focus on the international audience (international attendees more than 30%) |

| Mobility | Existence of mobility plan | Mobility plan not present |

| More days | Only one day | More days without an extra COVID safety service |

| Indoor time | Outdoor, less than 6 hours indoor per day | More than 6 hours indoors per day |

| Interaction | Preventative measures to reduce the risk of interaction | No preventative measures are in place to reduce the risk of interaction |

| Noise | Visitors make noise no louder than normal (60 dB) | Visitors make noise louder than normal (60 dB) |

| Drink, food | Adopting retail sector protocol on serving drinks and food | Not adopting retail sector protocol on serving drinks and food |

| Registration | Registration at entry | No registration at entry |

| Counting presence | Counting presence to guarantee density restriction | No counting of presence to guarantee density restriction |

| Disinfection | Existence of hygiene plan to prevent COVID | No hygiene plan to prevent COVID |

| Crowd management plan | Existence of a crowd management plan | No crowd management plan exists |

| Hygienic facilities | Existence of a hygiene plan | No hygiene plan exists |

| Informing, enforcing | Existence of an information plan |

Following a risk assessment, it is crucial to define the risk mitigation measures in terms of crowd management, social distancing, welfare, medical treatment, hygiene and toilets, transport to/from the site (i.e., vehicles) and measures against potential hazards such as accidents, security issues and fires (WHO, 2020b). Table 3 presents an example of risk mitigation measures for event organisers issued by Wakefield in the United Kingdom. Other event protocols shared similar risk mitigation measures to those in the event protocols from Event Flanders (e.g., seating arrangement, enforcement plan and dealing with infectious patients).

Table 3. Risk mitigation measures for events: An example of policy guidance (Wakefield, 2021)

| Elements | Risk mitigation measures |

|---|---|

| Crowd management | Capacity calculation in stewards and venue; identify pinch point/junctions; assess social distancing measurements; stagger arrival/leaving times or temporary barriers to prevent crowds or surges |

| Social distancing | Maximum group number; one way; sideways queuing; |

| Mobility/transport and vehicles to/from site | Ensure sufficient parking and no additional pressure on public transport |

| Welfare, medical treatment, hygiene and toilets | Quarantine areas close to medical/first aid locations; access to hand-washing facilities or hand sanitiser to allow for continual hand hygiene; cleaning of door handles, facilities, toilets and tables; cashless systems |

| Hazards (accidents, security, fire and other incidents) | Social distancing while evacuating; avoid raising voices |

Table 4. Event space following a COVID risk assessment and mitigation measures

| Key issues | Description | Risk factors and mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Indoor or outdoor locations | Ensure social distancing requirement; indoor ventilation requirement | Physical distancing for walking and queuing; safe seating arrangement; safe indoor ventilation; outdoor activities to replace indoor ones; better utilisation of public space |

| Venue facility | Requirements need to apply to pandemic recommendations | Monitoring equipment and technology; indoor disinfection and cleaning; adding isolation room/space; medical post; digitalisation |

| Transport infrastructure | Safe mobility for participants/spectators | Adhere to physical distancing in public transport system; digitalisation in crowd control |

Therefore, the risk mitigation measures have inevitable consequences on adjusting event-related space (e.g., indoor and outdoor space), venues and transport infrastructure (Table 4). The requirement of social distancing in indoor and outdoor spaces leads event organisers to either reduce the capacity to ensure social distancing or move activities from indoor to outdoor spaces. Correspondingly, specific functions should cover testing, isolation and medical treatment, which must be incorporated in master plans and venue designs.

Although all host cities and event organisers are confident about rescheduling their mega-events soon, a series of measures for social distancing, disinfection, quarantine and monitoring during social gatherings is being explored to prevent virus transmission and outbreaks. Event organisers in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands have conducted experiments using modern technology to detect the exact risks of mass gatherings in specific locations/spaces (Ellyatt, 2021; Fieldlab Evenementen, 2021; de Vrieze, 2021). Despite controversy in the research design and research results, these experimental results reflected the consequent risk mitigation measures with specific requests for extra indoor and outdoor space—often at the expense of reduced venue capacity and the provision of additional outdoor public space. All the aforementioned measures can increase the financial burden on hosts while also requiring much more human resources for related activities.

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 impacted nearly all major mega-events in 2020 and 2021 since most countries restricted or banned mass gatherings and international travel. Most event organisers experienced the cancellation and postponement of the events they prepared (Evans et al., 2020). Even when events resume, mega-event organisers must conduct risk assessments and risk mitigation measures to ensure social distancing, hygiene and other safety measures. Consequently, these mega-events cannot use their maximum capacity and must substantially reduce the number of visitors. As a result, the Eurovision Song Contest was finally held after a one-year suspension, with the presence of 3500 audience members and 20% of Rotterdam Ahoy’s capacity. Simultaneously, event organisers need to mobilise additional capital, resources and human resources to conduct risk mitigation measures. This has caused event budgets to increase, forcing event organisers to seek additional financial resources.

Despite a tough time ahead, the global vaccine rollout seems to be restoring a certain level of societal and economic normalcy in some countries in 2021. ‘Pandemic vaccines can mitigate much of the harm caused by infection by protecting individuals, stopping transmission, or both’ (Williams et al., 2021). Based on this new development, most host cities and event organisers still have confidence in the recovery of mega-events. Many have indicated the specific modifications required to cope with current pandemic-related challenges. On the other hand, local stakeholders—especially local citizens—show mixed feelings towards mega-events. While people desire to participate in social gatherings after lockdown, there remain concerns regarding potential outbreaks and complex financial situations encountered by event organisers. Consequently, the following question related to the future development of mega-events has emerged: How can mega-events become future-proof to challenges in the post-pandemic era? Should mega-events start to use the pandemic as a catalyst to make future mega-events more resilient?

While the concept of urban resilience emphasises the ability to bounce back ‘in the face of a disturbance’, it also refers to the ability of an urban system ‘that quickly transforms systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity’ (Klein, Nicholls, & Thomalla, 2003; Meerow, Newell, & Stults, 2016). Consequently, resilient mega-events should address ‘the vulnerability’ of current mega-events ‘in the face of a disturbance’ and the ability to ‘adapt to change’ in future mega-events (Meerow et al., 2016). The vulnerability of the mega-events has been reflected in the risks mega-events encountered during the pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mega-events face enormous risks in crowd management and social distancing. This is also the case when the risk of transmitting the virus needs to be minimised in indoor venues or public transportation systems. It is crucial to highlight the distinction between the short- and long-term adaptations addressed by Pike, Dawley, and Tomaney (2010). Moreover, it is essential to focus on maintaining ‘general’ resilience to unforeseen threats in addition to ‘specific’ resilience to known risks (Walker & Salt, 2006). Lessons from the adapted Antwerp 1920 Olympics show that mega-events such as the Olympics can inspire host cities to develop resilience and adaptation abilities (Constandt and Willem, 2021).

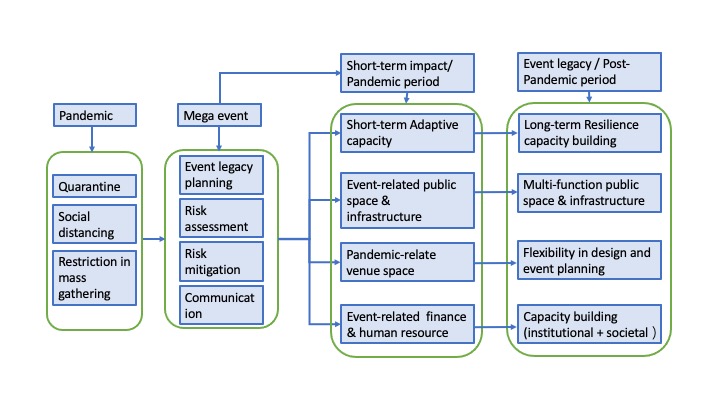

Figure 1. Event legacy creation via the resilience path amid and during the post-pandemic era

To apply adaptability to future mega-events, event organisers and host cities should consider a number of issues (see Figure 1). First, it is crucial to incorporate flexibility into the design and use of venues and how the activities can be carried out with more options and diversity. Second, the pandemic may drive future events to explore the transformation of public spaces such as parks, squares, streets and other outdoor spaces for crowd entertainment or social meeting places (Smith and McGillivray, 2020). Third, event planning should be comprehensively integrated into a host city's urban vision while emphasising future-proof features and long-term adaptability. The vision of legacy creation should be incorporated in the institutional setting and carried out with the joint force of broad societal forces. As London's legacy planning has demonstrated, event planning should address temporary urban development and establish appropriate conditions for future urban development. Fourth, formal requests for host cities, such as One City-One Game, should be re-examined if they have been obstacles to creating resilient mega-events and result in an unsustainable event legacy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed one of the most difficult challenges in the history of mega-events. The measures of social distancing, prohibitions on mass gatherings and travel restriction to counter COVID-19 transmission counter all of the key features that define mega-events and what they aim to achieve—a massive number of visitors participating in indoor/outdoor social gatherings. Based on the WHO guidance for mass gatherings, event organisers made risk assessments by considering the event type, scale and the type of space that can accommodate physical distancing. Correspondingly, event organisers have developed risk mitigation measures to reduce foreseen risks. These measures include reducing the capacity for receiving visitors, adjusting event-related indoor and outdoor spaces, and rearranging venues and transport facilities. While most host cities are confident in the future of mega-events with the help of vaccines, event organisers have inevitably adjusted mega-event programmes by adding new functions, spaces and facilities while also mobilising extra finance to cope with health risks and uncertainty.

Before the global pandemic, mega-event strategies involved strategic choices for host cities to create positive changes in the host cities. Research on event legacy creation has focused on how host cities use mega-events to comprehensively impact buildings, districts and cities in the post-event period through economic, spatial and social development (Chen et al., 2013). Legacy planning can be integrated into the master plans of host cities to catalyse urban regeneration through new venues, facilities, public spaces and infrastructure development. The turbulence that mega-events face during the pandemic emphasises the need for future mega-events to have the adaptability and capacity to rapidly respond to—and recover from— known risks. Future mega-events can be better organised to improve their resilience by carefully planning, preparing, and ensuring flexibility in adaptation and risk mitigation. Simultaneously, now is the right time to ask whether certain preconditions of mega-event hosting (e.g., One City-One Game) are still appropriate or need modification to develop resilient mega-events in the future. In this manner, host cities can optimally explore mega-events and exert less effort in dealing with long-term spatial, financial and social burdens.