2022 年 10 巻 4 号 p. 146-160

2022 年 10 巻 4 号 p. 146-160

With the increase in the recent pandemic conditions, the importance of closed community open spaces has gained a lot of importance in satisfying the need for public spaces within an urban fabric. Also, the real-estate trends have always publicised the presence of common public facilities within the gated communities, such as play parks, street furniture, temple, etc., an extreme luxury compared to any other residential facility available in the city. However, it is crucial to analyse its age appropriateness to understand whether these spaces can effectively engage users of varied age groups. Doing so will also result in a comprehensive conclusion to interpret activeness and safety. The study is performed within two planned mixed housing gated communities with multiple pockets of open spaces intended for recreation and leisure. This paper attempts to identify major physical and ambient features that commonly result in a more age-appropriate space. Since the findings are derived based on quantified subjectivity, the study includes a questionnaire survey, activity and behaviour mapping, and critical analysis of the physical setup. This study discusses various case-specific design decisions that can be employed to establish more inclusive open spaces within a gated community by analysing attributes such as zoning, proximity to allied activities, territoriality, and defensibility. Since the findings highlight the behavioural needs emerging due to the coexistence of demographic age ranges. This study would be beneficial for architects, landscape architects and urban designers to create age-appropriate open spaces.

It is forecasted that by 2050, two-thirds of the world's population will be living in cities (Hejne, 2011). The design of cities plays a key role in urban accessibility and mobility to improve communal and interpersonal interactions. According to the World Health Organization (WorldHealthOrganization(WHO), 2010), the living conditions in the urban environment are key to the health and well-being of its residents. The physical and non-physical attributes of neighbourhood open spaces are known for promoting healthy living for their users by offering various physical and psychological health benefits (Chiesura, 2004; Konijnendijk, Annerstedt et al., 2013; Lee and Maheswaran, 2011; McCormack, Rock et al., 2010; Nasution and Zahrah, 2014; Payne, Orsega-Smith et al., 2005). There is also evidence about the association between the physical characteristics of parks such as size, safety, location, access, infrastructure, aesthetics, maintenance and the level of physical activity of users (Bedimo-Rung, Mowen et al., 2005; Kaczynski, Potwarka et al., 2008; McCormack, Rock et al., 2010). Several researchers also analysed the relationship between neighbourhood open space and the quality of life. Though there are many studies on the health benefits and mental well-being achieved by the use of parks, not much attention has been given to the study of how the architectural design of such parks could enhance social interaction and communication in closed communities (Buckley and Brough, 2017). The neighbourhood open spaces with a high green coverage rate have high ecological and environmental importance (Dean, van Dooren et al., 2011; Givoni, 1991). Further, these green spaces could improve the climate, reduce the urban heat island effect and reduce pollution (Heidt and Neef, 2008). Hence, the urban planners and designers should aim to create cities that are receptive and responsive to their inhabitant's needs. Traditionally, common open spaces found at the centre of the temple grounds, clustered houses and thinnai along the street were conceived as the neighbourhood open spaces for recreation in Tamilnadu, India. Earlier, Streets were the spaces used for mobility and children to play and elders to socialise (Mahgoub and Khalfani, 2012). With an increase in vehicular mobility and change in the concept of settlement planning, modern open spaces such as Play Park, courtyards, footpaths, waterfronts, plazas and town squares also strive to provide such a vibe of life by satisfying the modern needs of the residents with their physical settings and supporting amenities. A gated community is a form of residential community or housing estate containing strictly controlled entrances for pedestrians, bicycles, and automobiles. It is often characterised by a closed perimeter of walls and fences with planned spaces for recreation within its boundary (Lee and Maheswaran, 2011). Trends in real estate for the housing sector have shown a tremendous increase in the demand for gated communities because of their capability to provide investors with adequate comfort and a choice of facilities within the closest proximity. Also, studies prove that there has always been a strong reason for people to choose gated communities over any other housing models as it provides security, status, lifestyle and sense of community (Landman, 2000; Molin, 2011; Salah and Ayad, 2018; Wilson, 1999). Many studies have further investigated the sense of security and community these gated communities have been able to provide and resulted in appreciating the presence of several gates, fences, and social groups for the same (Sakip, Johari et al., 2012). However, in the recent past, there have been a lot of witnesses to crimes within such closed communities which considerably raised parental concerns regarding child safety. Studies have proved that despite providing a sense of security for the adult, the gated communities have failed to improve the parent's perception of defensible space for their children (Shamsuddin, Zaini et al., 2014).

With more such concerns and limitations, providing open spaces and parks in such closed communities pose a major challenge to the success of these acclaimed facilities and facilitating the social interaction needs of the residents of the gated communities (Aulia and Ismail, 2013; Nasution and Zahrah, 2014). Attempts to answer these concerns have led to the understanding that not just the presence of various facilities counts for an active and safe environment but the planning of a physical environment that allows for active participation of the residents regardless of their ages and establishes a holistic success.

A recent study on the sense of community within gated and non-gated residential communities concluded that the residents in Individual Non-Gated Residential Communities (INGRC) had a higher sense of community than those in Gated Residential Communities (GRC). The paper also suggests that the social interactions are enhanced by the physical design of the environment that encourages them to go out for recreation (Sakip, Johari et al., 2012). Similar studies validate that the physical design of open spaces within gated communities is required to considerably improve the sense of community by encouraging the residents, regardless of their age group, to actively engage in these open spaces (Mirzaei, Zangiabadi et al., 2021).

Ensuring the health and well-being of residents ought to be a prime concern of all societies. But there is a lack of similar studies in a developing country, which faces the degradation of the urban environment and the quantity and quality of public open spaces. Hence, the vulnerable groups, especially the elderly and the children in India, pose a major challenge. The quality of neighbourhood open space can be viewed from two aspects: the function and the physical features. The function relates to the activities which people carry out in open space and the accessibility of that space. The significant physical features expected in such spaces are the presence of clear pedestrian pathways and connectivity with the surroundings and infrastructure for comfort, such as street furniture and shade.

Human behaviour in many cases will be an outcome of the physical, social, cultural or sensory influence of open space or environment. The users can also influence their form and feel by introducing social characteristics and elements such as culture, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and age. Together with the physical and ambient (or nonphysical) features of the public space, these elements can have a profound effect on how people behave, experience, and interact in public spaces (Bendjedidi, Bada et al., 2018).

This paper identifies the major physical and ambient features that commonly result in a more age-appropriate open space from the two selected gated communities in the Indian city of Madurai, a sprawling metropolis with a population of more than 3.4 million. It also explores all possible architectural considerations that could be incorporated in the planning strategies for the physical and ambient environment of the neighbourhood open spaces to achieve a productive environment. The results will aid in improving the quality of life of its residents, especially from the perspective of vulnerable users, like the elderly and children.

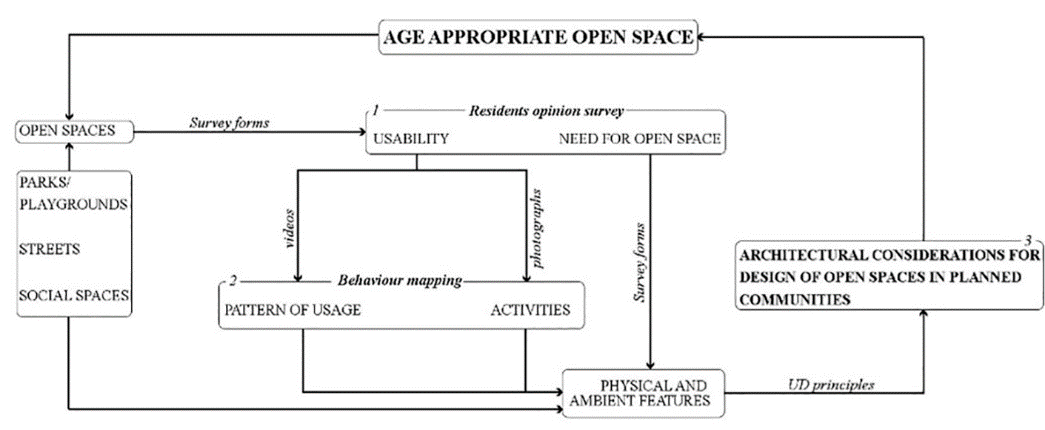

Architectural design proposals are subjective where one's need for comfort, safety and aesthetics, etc., might differ from the other. However, to derive a common ground and increase the generalizability of these subjective opinions, there is a need to quantify the common opinions exhibited by several users. This study aims to identify the design strategies that can potentially enhance the age appropriateness of open space within such planned neighbourhoods by objectifying the subjectivity. A minimum of two case studies hosting populations from different social spectrums but with similar structural organizations of open spaces is essential. This research is an evidence-based descriptive study and has employed three methodological approaches: a questionnaire survey, activity and behaviour mapping, and critical analysis of the physical setup based on existing theoretical knowledge as shown in Figure 1.

First, residents' opinion surveys were conducted to analyse and understand the needs of various age groups and the usability of the existing open spaces in their physical setting. For the purpose of the same, the residents were classified into different age groups as 5–12 (Kids), 13–19 (Teens), 20–39 (Young Adults), 40–59 (Adults), 60 and more (Elderly). A sample size of 60 for every age group was prefixed. Park users were requested to participate in the survey using a questionnaire focussing on their age, gender, frequency of use, sense of ownership, personal space invasion, the significant activity they participate in, restrictions in performing their daily activities, and natural surveillance. It took 5 minutes per person to complete this survey. On weekdays, counts of visitors were taken at the entry gates, which helped to know the total number of users during peak hours. The frequency of visits was measured daily (at least five days in a week), weekly (once or twice a week), and rarely (once in a month). The distance from the park was measured as within 500m (5min walk), 500– 1000m (10min walk) and more than 1000m (more than 10 min). Secondly, the behaviour and activity mapping of the residents are recorded in the form of short videos and photographs and later converted into diagrams by the author to evaluate the factors that affect their behaviour in performing a specific activity within a particular place within the demarcated open space at various times of the day. Thirdly, the physical setting and ambient features of the planned open spaces were observed and analysed to extract the architectural strategies provided to improve the quality of life and its shortcomings.

In recent times Madurai city has started to witness the development of planned neighbourhoods in contrast to its organic traditional residential communities. The study has been carried out within two selected residential gated communities, namely AGRINI and SHANTHI SADAN, in Madurai, the temple town situated on the bank of river Vaigai at a distance of 470 km southwest of Chennai, Tamilnadu, India.

The two residential gated communities chosen are located within the city's urban core, comprising a relatively similar mix of housing typologies with a similar open space structure. Both sites carry a gated community's typical safety and management system but with different site layouts and physical design characteristics. They also have several pockets of open spaces clustered either along with the housing units or the streets for recreation, as shown in Figure 2. Open spaces in the selected case studies are treated with similar materials and furnished with similar outdoor furniture and planting patterns. The area of the two case studies selected differs (Agrini - 50 Acres. Shanthi Sadan -15 Acre). The attributes that define the liveability, such as the population density, residential density, and percentages of open spaces, are figuratively similar, thus aiding in a better comparative analysis of the considered parameters (Table 1).

| Study site 1 Agrini | Study site 2 Shanthi Sadan | |

|---|---|---|

| Area | 50 Acres | 15 Acres |

| Population | 8800 | 2891 |

| Number of units | 2000 | 657 |

| Household size | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| Population density | 44000/Sq.km | 48180/sq.km |

| Residential density | 40/acre | 43.8/acre |

| Percentage of open space | 10% | 10% |

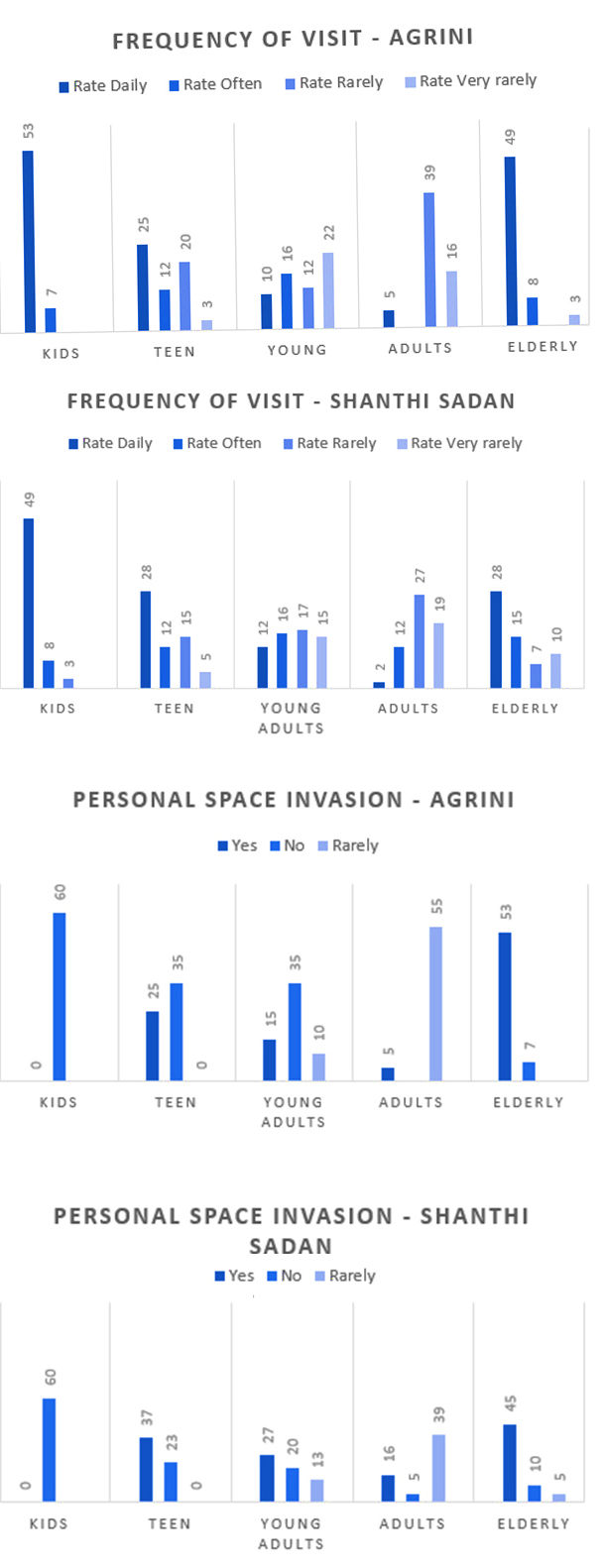

The residents' opinion survey responses have been consolidated and compared in the form of bar charts, as shown in Figure 3. Apart from the resident's opinion survey, the number of people per hour (PPH) within the study sites was counted manually to substantiate the frequency of usage of the open spaces within the gated community. It was found that Agrini had 103 PPH on weekdays and 173 PPH during the weekends, and Shanthi Sadan had 20 PPH on weekdays and 48 PPH during weekends. The results reveal that the parks and other open spaces are preferred mostly by the children and elderly. From the results, it is also observed that the teens have a feeling of personal space invasion due to various reasons like the presence of many people around or the feeling of being overlooked by the movement in the close vicinity. They often avoid using these spaces for recreation.

However, various studies and concepts in space planning, notably Jane Jacobs' eyes on the street concept' - have always encouraged the attribute of a park or an open space to be clustered around buildings with windows and openings overlooking the space to improve the visual surveillance.

The behaviour and activity mapping were carried out to understand the behaviour and activities performed by the residents at various times of the day. The observations are mapped in the form of a matrix and section (Figure 4 and Figure 5), as shown below. It is observed in both the study sites that the users mainly engaged in activities like playing both structured games (Shuttle, basketball and Kho Kho) and unstructured games (local games without formal rules and play equipment), exercising, temple visit, sitting, standing, people watching, socialising (chatting) during various timing of the day. For the purpose of study, activities that require physical effort have been considered active, and those that require no physical effort and exertion have been considered passive.

The above matrix is based on the observation made on-site, and it indicates different activities performed by various age groups at different times of the day. The users are observed to have been performing activities based on the availability and position of play equipment, amount of shade and seasonal comfort, etc. This indicates that the park users are involved in minimal active and more passive activities during the weekdays. In contrast, people are involved in more active engagements during the weekends like playing, exercising, visiting temples, etc. It is also observed that the furniture and shade play a significant role in improving the users' comfort, hence allowing them to spend more time in the park. Proper positioning of furniture becomes an essential criterion in inviting the elderly to the park. It is observed that the seaters placed in proximity to an active playfield are more often avoided, and the seaters zoned off an active field with some buffer, but visually connected are more preferred as shown in Fig.6. Precisely, it is evident that any physical barrier (parked cars, fences, raised plinth or vigorous physical activities performed by the co-users) that requires more physical effort and careful surpass is mostly avoided by both elderly and kids.

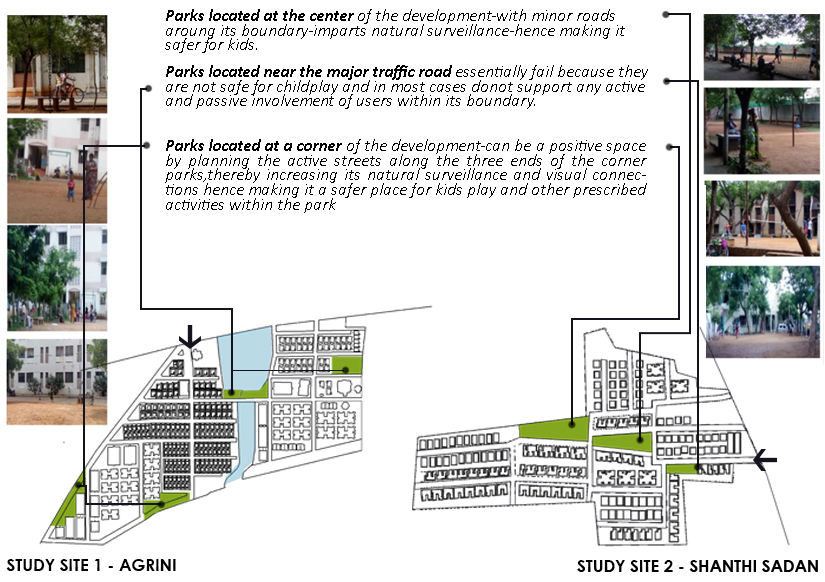

The location of parks or open spaces intended for recreation and leisure within the neighbourhood is observed to study its impact on the users. Figure 6 shows that parks located at a corner of the development with active streets along the three sides could be a positive space because of their increased natural surveillance and visual connections. It will make the space a safer place for kids to play and others to engage in active/ passive activities within the park. Parks located at the centre of the development with minor roads around its boundary also impart natural surveillance, making it safer for kids. And the parks located near the major traffic road essentially fail because they are not safe for child play and, in most cases, do not support any active and passive involvement of users within their boundary.

Territorial reinforcement in conceiving space as a single unit combined with varied activities ensures a sense of ownership and challenges intruders. Territoriality by physical barriers imparts a different sense of ownership where when a category of age group uses the park, the other category hesitates to use the park. Visibility and natural surveillance are major issues for teens to choose the hidden edges of the park, which are avoided by kids, young girls, and women (Figure 7). It is observed that the parks surrounded by streets or internal roads that are used daily or at least more often by the users impart a stronger sense of ownership than the one which either has an exclusive path or is at the corner of the settlement. It is observed that, though the users only surpass the park, they have a strong visual connection to the space and witness the space's ambience like its view, shade, activeness, etc., which eventually adds to their overall experience of the space (Figure 8).

It is also to be noted that such involuntary participation in space develops the sense of ownership and improves the overall sense of security of the park or open space, making it a more preferred space for daily outdoor engagement for all users. This also ascertained the need to technically treat the spaces that connect the apartment lobbies, site offsets and streets with these open spaces as part of the design to seemingly merge the functions that all these spaces would offer individually. Connecting the parks and open spaces through pedestrian circulation routes will aid in involuntary participation, thus imparting a stronger sense of ownership. It may include multiple tree-lined shaded streets, wide paved walkways, or small rubble alleys that offer armed benches for resting and socializing and service lanes to buffer vehicles and pedestrians.

The traditional form of Indian outdoor engagement, regardless of age group or gender, has always been on the streets. Such engagement can be kids' play, women socialising, using streets as an extension of private space to dry rice grains, hanging clothes, conducting social gatherings for family function or temple ceremony, protests, etc. With their relation to the surrounding elements like residential plinths (thinnai, otla, balcony), chathram, temple grounds, and playgrounds, streets have imparted a strong sense of community amongst their users with their varying degree of publicness and also reassured the need for public engagement for all age group. With the adaptation of various cultural shifts and changes in space planning trends, parks and public open spaces have become some of the highly preferred forms of public engagement. However, a person's association with the streets has always been assured through various observations, documentation, and studies. Hence it is also essential to consider the streets as extensions of the parks and open spaces. This can be achieved through various architectural design considerations such as street width, paving material and usage of speed breakers to reduce the speed of vehicles, wider sidewalks, installation of street furniture, planting trees to improve street shading, etc. Constant visual connection and natural surveillance are seen to be more in parks with active spaces in their immediate surroundings. Like in study site 1, such active spaces can be streets with furniture, temple ground, the plinth of the residential flat with a broad array of stairs that supports socialising, or an active lobby opens to the park or open space. Planning of parks with dead spaces like parking lots or compound walls in its boundary like in study site 2; increases the ambiguity of the space and increases the risk of threat which makes the space least preferred and less active. Having an active public space next to a park or an open space makes it more inviting for all the users by providing various opportunities for engagements within the park and its surroundings without hindering the private space of the co-user, as shown in Figure 9.

Both the case studies presented in the study managed to offer appropriate settings only to a specific demographic range because of their inadequate design consideration. However, both the case studies had preferable conditions under which the open spaces temporarily became age-appropriate. In Agrini (Study site 1), the parks/open spaces have adequately screened visual connections. The streets abutting the park and open spaces were treated with similar design strategies, offering to be an extension of open space and aiding involuntary participation. It was observed that the park and the open spaces were extremely inviting for all age groups because they were on the same level as the abutting street and are not guarded by a fence. However, the parks/open spaces in Agrini were abutting non-active allied spaces such as parking lots, apartment rear setbacks, and compound walls. In most cases, it became a threat to young adults (women) as they offered negative spots for illegal activities. In Shanthi Sadan (Study site 2), the parks and open spaces were completely visually connected and naturally surveyed, which were safe for kids by supporting defensibility; however, this limited the participation of teens and adults. Additionally, the open spaces were raised by the plinth height and guarded by fencing, which in most cases were intimidating, especially for the aged people hence falling short in establishing ownership and involuntary participation. However, the open spaces were abutting allied spaces that offered related recreation and relaxation facilities for demographics from all age groups, increasing the opportunities for coexistence, if not within the open spaces' physical boundaries, at least in the closest vicinity.

A park or any open space hence to be inviting to all age groups must ensure that it is not exclusive and in complete disconnection from its immediate environment requiring any volunteering effort to reach the space. Preferably it has to be located along the daily route of its user and should have physical and ambient surroundings within its immediate next for effective engagement of various activities cohesive irrespective of varied groups of users. A park is a shared public facility within a gated community which essentially has to serve all the users regardless of age group and gender, unlike in many cases where its primary target is kids and the elderly. This notion of age appropriateness is highly achievable by considering and implementing various architectural/planning considerations in setting the physical and ambient features of parks and various open spaces.

This study discusses various case-specific design decisions that can be employed to establish more inclusive open spaces within a gated community by analysing both its physical and ambient features such as zoning, proximity to allied activities, territoriality, and defensibility. Consideration for physical attributes includes zoning of parks or open spaces within a cluster of residential buildings, active but slow traffic streets or besides allied active space; avoiding fencing, parking cars or any physical barriers; planning the space with various physical features of comfort and space like shading, furniture, play/park equipment, etc., thus making it engaging irrespective of age group; planning open spaces and parks as an extension of streets hence imparting a sense of ownership. Likewise, ambient attributes of the open space include setting the degree of publicness or territoriality by limiting visual connection without affecting the opportunity for natural surveillance. This can be achieved through architectural considerations that include changing the direction of facing of setters (opposite playfield); increasing the distance between the setters and play area without thoroughly screening it from view; providing semi-public or screened open spaces for passive engagement. Thus, the paper explores the opportunities through architectural considerations to achieve a park or an open space within a gated residential community age-appropriate rather than just a space that only engages certain age groups. The findings of this study would be beneficial for architects, landscape architects and urban designers to create age-appropriate open spaces within gated communities by highlighting the behavioural needs emerging due to the coexistence of demographic age ranges.

Conceptualization, S.P.; methodology, S.P. and C.I.; software, S.P.; investigation, S.P.; resources, S.P. and C.I.; data curation, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and C.I.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and C.I.; supervision, S.P. and C.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.