2025 年 13 巻 4 号 p. 149-172

2025 年 13 巻 4 号 p. 149-172

Abstract: Ecovillages are communities designed through locally owned, participatory processes to integrate social, cultural, ecological, and economic dimensions of sustainability, aiming for development that meets current needs without compromising future generations. Critics argue that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) face challenges due to vague action plans. In contrast, as experimental grounds for sustainable living, ecovillages provide concrete explorations of the SDGs. However, comprehensive analyses of their contributions to the SDGs remain limited. This study addresses this gap through a thematic review of literature published between 2020 and 2024 in Scopus and Web of Science. Using inductive coding and axial grouping with ATLAS.ti, the analysis reveals five key themes, encompassing the domains of Rural Development, Educational Approaches and Learning, Social and Innovative Economic Practices, Sustainability Models and Practices, and Landscape and Rural Design. The findings demonstrate that social and economic practices are the most frequently addressed themes, while spatial and design-oriented strategies have gained increasing attention in recent years. Ecovillages promote SDG advancement through grassroots innovation, place-based learning, renewable energy experimentation, and culturally grounded practices, despite notable regional disparities in research. This study also highlights the policy relevance of ecovillages as bottom-up alternatives to top-down SDG implementation, underscoring the need for adaptive governance frameworks that support community autonomy and context-sensitive sustainability transitions.

An ecovillage is fundamentally a community that is consciously designed through locally owned participatory processes to holistically integrate social, cultural, ecological, and economic dimensions of sustainability. According to the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN), an ecovillage can be an intentional, traditional, or urban community that aims to regenerate its social and natural environments through sustainable practices. This concept is rooted in the idea of creating settlements where human activities are harmoniously integrated with the natural world, supporting healthy human development that can be sustained indefinitely (Gilman, 1991).

Since emerging as a global movement in the 1960s and 1970s, ecovillages have evolved into diverse forms that apply sustainability in daily life, often drawing on local traditions and adapting solutions to their specific socio-environmental contexts (Bakó, Hubbes, et al., 2021; Lennon and Berg, 2022). The movement has witnessed significant growth, with over 10,000 ecovillages currently registered worldwide, forming regional and global networks dedicated to societal transformation (Price, Ville, et al., 2020). In response to dominant societal trends, such as global economic systems, consumer culture, and environmental degradation, ecovillages advocate for more liveable and humane ways of life, grounded in self-sufficient practices that promote both ecological integrity and social well-being (Farkas, 2023). Their vision is operationalized through a range of practices including bioconstruction, permaculture farming, renewable energy systems, ecological education, and other community-based sustainability initiatives (Cisek and Jaglarz, 2021; Esteves, 2020; Germundsson and Sanglert, 2024; Szabó, Prohászka, et al., 2021). These initiatives enhance inhabitants' quality of life while producing transferable insights for sustainable development, providing models that can guide wider transitions toward sustainability (González-Arnedo, Izquierdo-Gascón, et al., 2022; Saadi, Antoni, et al., 2022).

In parallel, sustainable development, a concept that emerged prominently in the 1970s, was first globally defined by the Brundtland Commission in 1987 as “development which meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987). This definition underscores the balancing act between economic growth, environmental stewardship, and social inclusion, forming the basis for the contemporary SDGs established by the United Nations in 2015. The SDGs aim to redirect global efforts towards sustainability through a comprehensive framework encompassing 17 goals, addressing diverse aspects from poverty eradication to environmental conservation (McIntyre‐Mills, 2020).

However, critics argue that the SDGs often suffer from vague, top-down implementation mechanisms that lack concrete action plans, enforceability, and sensitivity to local contexts (Easterly, 2015; Henfrey, Feola, et al., 2023; Leal Filho, Vasconcelos, et al., 2022). In response to these limitations, bottom-up, community-driven approaches such as ecovillages offer valuable, place-based insights into how SDGs targets can be achieved through daily practice and democratic engagement (Crowley, Marat-Mendes, et al., 2021; Syamsiyah, Sulistyowati, et al., 2023). Ecovillages exemplify how abstract sustainability goals can be transformed into grounded, actionable strategies tailored to specific local contexts. Through applying a range of locally adapted practices, they align directly with multiple SDG targets. For instance, they support SDG 7 by adopting renewable energy technologies that reduce reliance on fossil fuels and enhance local energy autonomy (Ho, Hashim, et al., 2014). They contribute to SDG 2 through permaculture, seed saving, and community-supported agriculture that promote food security and agroecological resilience (Birnbaum and Fox, 2014). In the education domain, ecovillages advance SDG 4 using non-formal, experiential learning focused on ecological literacy and intergenerational knowledge exchange (Pathiraja, 2007). Inclusive governance and gender participation help fulfil SDG 5 and SDG 16, strengthening democratic structures and promoting social equity at the local level (Nelson, 2018).

Despite these promising contributions, existing scholarship on ecovillages remains largely fragmented. Most studies focus on single cases or specific thematic areas, lacking a systematic synthesis of how ecovillage practices collectively align with and advance the SDGs. Moreover, few studies have examined these dynamics within the context of recent global disruptions. To address this gap, this study conducts a thematic review of literature published between 2020 and 2024 to identify the common mechanisms through which ecovillages contribute to sustainable development. This research offers a cross-contextual synthesis grounded in contemporary challenges and provides timely, actionable insights into the potential of community-based models to translate global sustainability frameworks into localized, participatory practices. The study is guided by the following research question:

What are the common factors of ecovillages contributing to achieving Sustainable Development Goals discussed in the publications from 2020 – 2024?

This study adopts the thematic review flowZ (TreZ), a methodology introduced and copyrighted by Zairul (registration no. CRLY2023W02032), which utilizes ATLAS.ti 23 and aligns with established thematic analysis procedures in literature reviews (Zairul, 2023). TreZ is employed to systematically code, group, and interpret data from selected literature, following the structured steps outlined in Figure 1 (Zairul, 2021b, 2021a; Zairul, Azli, et al., 2023; Zairul, 2020). Clarke and Braun (2013) define thematic analysis as a process of identifying the patterns and constructing themes through thorough reading on the subject (Clarke and Braun, 2013).

Initially, the process begins with formulating the research question (Formulating RQ) (see previous section), which serves as a roadmap for the subsequent stages of the review, establishing the focus and scope. Next, the articles screening step (Articles screen) (Table 1) involves identifying and preliminarily selecting studies based on their relevance to the research question. This is followed by the articles filtering stage (Articles filtering) (Figure 2), where inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied to refine the selection of studies, ensuring that only the most pertinent articles are retained for further analysis. The fourth step, cleaning (Cleaning process), involves a thorough double-checking of the metadata of the articles to ensure accuracy and completeness of the data collected. The final step in the process is data extraction (Synthesis & reporting), where a thematic analysis is conducted using tools such as ATLAS.ti to develop themes based on extensive reading of the subject matter in the selected articles. This structured approach enhances the reliability and depth of the review, ensuring a comprehensive analysis of the literature.

| Database | Search String | Results |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "eco*village*" OR "eco-village*" ) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , "english" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE , "final" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( OA , "all" ) ) | 60 results |

| Web of Science (WoS) | Results for "eco-village$" or "eco*village$" (All Fields) and Open Access and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages) | 58 results |

The next step involves identifying patterns and constructing categories to understand trends related to ecovillages and sustainable development in literature from 2020 to 2024. This phase aims to interpret the findings and propose directions for future research into ecovillages as a specific means of sustainable development. This approach will be instrumental in clarifying the evolution of these trends and highlight emerging innovations critical to advancing the field. To ensure a comprehensive and relevant analysis, the selection of literature was guided by specific criteria: 1) the publication date range from 2020 to 2024, ensuring the research is current and significant; 2) the inclusion of key terms such as 'ecovillage' in the literature, to focus on studies that are directly relevant to the main themes of this research. This methodical selection process helps in capturing a broad spectrum of contemporary insights and developments in these fields.

The literature review was conducted by searching two major academic databases, Scopus and Web of Science, chosen for their comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals relevant to circular economy principles within the construction industry and built environment. In Scopus, the search was defined with the keywords "eco*village*" OR "eco-village* in the title, abstract, and keywords (TITLE-ABS-KEY), targeting publications from 2020 to 2024, and restricted to academic articles in English that were open access (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, "ar"), LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, "English"), LIMIT-TO (OA, "all")). This search strategy resulted in 60 articles, indicating a substantial body of recent literature. Meanwhile, the results obtained using Web of Science are similar to those from Scopus, using the same keywords across all fields without specific field restrictions, and focused only on open-access articles in English. This approach yielded 58 results. The number of articles retrieved from each database may reflect variations in their indexing depth, journal coverage, and search algorithm specifics, providing a diverse array of articles for review.

To ensure methodological rigor and transparency, a structured selection process was designed and implemented (Figure 2). After merging the results from both databases, 47 duplicate records were identified and removed to ensure the uniqueness of each source. The remaining articles were systematically screened in accordance with the study’s research aims. During this phase, 18 records were excluded for not meeting the necessary criteria, resulting in a final sample of 53 studies retained for thematic analysis.

In the qualitative analysis phase, this study employed ATLAS.ti 23 software in combination with an inductive, thematic analysis approach. ATLAS.ti was selected for its robust data management features, interactive coding environment, and well-developed visualization tools, particularly its network views and code co-occurrence mapping (Gupta, 2024; Smit, 2021; Smit and Scherman, 2021). Its widespread adoption in recent thematic analysis studies further supports its reliability and relevance for qualitative synthesis (Friese, Soratto, et al., 2018; Malek and Abdul Rahim, 2022; Soratto, de Pires, et al., 2020).

A thorough and recursive reading of the 53 selected articles was conducted, during which open coding was used to identify recurring concepts, keywords, and focal meanings across the literature. These initial codes were subsequently reviewed, reinterpreted, and refined through multiple rounds of comparison, memo writing, and re-coding. Axial grouping was then applied to abstract higher-order conceptual categories from semantically related codes.

The entire analytical process followed the six-phase thematic analysis framework proposed by Braun and Clarke (Braun and Clarke, 2019; Clarke and Braun, 2013) comprising 1) data familiarization, 2) initial coding, 3) theme construction, 4) theme review, 5) theme definition and naming, and 6) final reporting. Throughout the process, researcher subjectivity and reflexivity were actively acknowledged as integral to the interpretive act of theme development, in line with the principles of reflexive thematic analysis.

This section presents the main findings of the thematic review, which are structured into two parts: quantitative and qualitative results. The quantitative analysis first provides an overview of the thematic focus and publication years of the 53 selected ecovillage-related studies. It then examines the geographical distribution of publications by country. To complement this, a word cloud is included to illustrate the most frequently occurring terms across the literature, offering insight into prevailing research themes. In the subsequent qualitative analysis, an initial round of open coding was conducted in ATLAS.ti produced 9 first-order codes. Following successive rounds of re-coding and code merging, 5 significant themes were ultimately found among the trends and patterns.

As outlined in the introduction, the focus of this article is to understand the factors of ecovillages contributing to achieving SDGs. Despite the relevance of this topic, there remains a lack of comprehensive reviews in the past five years that examine ecovillages within a multidisciplinary and intersectional framework. This study adopts a logically structured research process that includes data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results, and is grounded in the insights of recent empirical and theoretical contributions.

Quantitative reportingThe Sankey diagram illustrates the thematic distribution and publishing years of research related to ecovillage (Figure 3). The themes include Rural Development, Educational Approaches and Learning, Innovative Economic and Social Practices, Sustainability Models and Practices, and Landscape and Rural Design. In 2020, there were 12 publications focused on Rural Development, Educational Approaches and Learning, Innovative Economic and Social Practices, and Sustainability Models and Practices.

Over the subsequent years, the thematic emphasis gradually shifted toward more integrative and spatially oriented themes. Notably, the theme of Landscape and Rural Design began to emerge after 2021 and gained increasing prominence. By 2024, this theme had become a significant focus of scholarly attention, reflecting a growing interest in the spatial configuration and environmental design of ecovillages. Meanwhile, the theme of Innovative Economic and Social Practices remained consistently active throughout the entire period, indicating its sustained relevance in ecovillage research across diverse contexts and years.

The following Table 2, which categorizes research articles across various aspects of ecovillages, provides further support for this observation. The predominance of articles on Innovative Economic and Social Practices, appearing in 20 studies. Rural Development ranks second with 14 publications. Both Educational Approaches and Learning and Sustainability Models and Practices are represented equally, each with 7 studies. Despite its growing visibility in recent years, Landscape and Rural Design remains the least represented theme with only 5 articles. This imbalance reveals a critical opportunity for future research: there is an urgent need to more organically integrate education, spatial planning, and landscape design into the ecovillage research framework, thereby advancing a more systematic and holistic pathway toward sustainable development.

The world map provides a visual representation of the geographical distribution of countries involved in ecovillage-related research (Figure 4). Among these, Portugal emerges as a notable focus with nine articles focusing on it, underscoring its significance in the field. In addition, countries such as Brazil, Germany, India, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom each appear in five publications, indicating substantial academic attention to their ecovillage practices. Similarly, China, Denmark, France, Hungary, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United States are each represented in four articles, reflecting their relevance in discussions surrounding ecovillage concepts and sustainable community development. This distribution highlights the wide geographical scope of ecovillage research and demonstrates the growing global interest in exploring sustainable living environments.

However, the limited representation of many regions, particularly those in Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Southeast Asia, indicates a significant geographical imbalance. This uneven distribution may result in a knowledge bias. To foster a more comprehensive and inclusive understanding of ecovillages, future research should aim to engage with underrepresented regions while taking into account diverse cultural, ecological, and socio-political contexts.

Figure 5 illustrates the word cloud generated from the 53 documents highlights key themes and concepts central to ecovillage research. Prominent among these are terms such as "ecovillage," "community," "sustainable," "development," "social," and "sustainability," underscoring the focus on creating cohesive, sustainable living environments. Other significant terms include "energy," "environmental," "local," "economic," and "cultural," reflecting the multi-dimensional approach required for successful ecovillage development. The word cloud also emphasizes the importance of "learning," "practices," "systems," and "research," suggesting a strong emphasis on education, practical implementation, and continuous study to advance the field. Additionally, words like "rural," "urban," "life," "health," and "food" indicate the broad scope of ecovillage studies, encompassing various aspects of daily living and well-being. In the next qualitative section, the themes will be examined in depth.

Figure 6 presents an overview of the current research trends related to ecovillages and their contribution to achieving SDGs from 2020 to 2024. It identifies five primary themes. Theme 1, "Rural Development," explores how ecovillages support rural revitalization through alternative lifestyles, policy support, and community-based infrastructure. Theme 2, "Educational Approaches and Learning," focuses on the educational initiatives and learning processes within ecovillages that promote sustainability awareness and skills. Theme 3, "Innovative Economic and Social Practices," highlights the implementation of alternative economic models and participatory social structures that strengthen community resilience and ecological responsibility. Theme 4, "Sustainability Models and Practices," investigates the practical implementation of sustainability models and techniques within ecovillages. Lastly, theme 5, " Landscape and Rural Design," examines the spatial and design-oriented strategies that shape the physical form and environmental aesthetics of ecovillages. This thematic overview reveals a strong academic interest in social innovation, sustainability practices, and the spatial dimensions of ecovillage development.

Ecovillages function as dynamic laboratories for rural development, illustrating the efficacy of localized, sustainable practices in addressing broader environmental challenges. They promote community-based approaches to rural development through the integration of sustainable practices, Figure 7 illustrates a selection of literature that engages with this theme.

Supporting these perspectives, Tysiachniouk and Kotilainen explored the emergence and functioning of intentional communities (ICs) in Crimea's Belbek Valley amidst geopolitical turmoil. The authors examine these communities through semi-structured and open-ended interviews, thematically analyzing their motivations and practices. The ICs in Belbek Valley are small-scale, alternative lifestyle experiments emphasizing low-carbon footprints, permaculture, energy and water-saving technologies, vegetarianism, and yoga. They stand out from adjacent traditional communities, emphasizing place-making over greater socioeconomic developments. The study highlights the paradox of ICs seeking long-term sustainability in a politically unstable environment. Despite the broader political challenges, these communities continue to thrive by emphasizing environmental practices and creating spaces for cultural and spiritual growth. The research also suggests the need for further studies on ICs in different political contexts to understand their varied motivations and sustainability practices (Tysiachniouk and Kotilainen, 2022). Similarly, Shirani, Groves, et al. (2020) illustrate the challenges and successes of a low-impact ecovillage as part of a sustainable rural development model. The article underscores the critical roles of policy support and residents' self-motivation in achieving sustainable development, providing valuable insights into how sustainable lifestyles can be realized in rural settings. The study by Saadi, Antoni, et al. (2022) explores residents' preferences regarding ecovillage dimensions across different geographical locations in France, aiming to determine the ideal proportions of an ecovillage. Through a detailed questionnaire and subsequent statistical and spatial analysis, the study reveals significant demographic insights, with a majority of respondents being young professionals with advanced degrees. Key findings highlight the importance of various dimensions such as transportation and access, economic sustainability, and social and agricultural cohesion. For instance, access to health services and proximity to urban centres are prioritized under transportation, while green farming and local production are emphasized in the agricultural dimension. The study also underscores the cultural dimension's role in fostering creativity and environmental conservation. These insights are crucial for planning and developing ecovillages that align with residents' preferences, ensuring their sustainable and holistic growth (Saadi, Antoni, et al., 2022).

Moreover, scholars have discussed various specific measures for ecovillage development strategies, such as policy support. Findings from South Korea demonstrate that with government support and policy incentives, it is possible to construct eco-friendly residential complexes, serving as a significant reference for future Zero Net Energy building projects (Moon, Jang, et al., 2020). Gao, Wang, et al. (2022) review the impact of Chinese government support and sustainability assessment on ecovillage development, highlighting how government funding and policies facilitate initial development but may lead to low industrial diversity and dependency on financial aid. They propose promoting industrial diversification and gradually reducing government support to enhance sustainability (Gao, Wang, et al., 2022).

Additionally, cultural narratives and traditions also contribute to constructing collective identities and fostering a sense of belonging within ecovillage communities (Andreeva, 2021; González-Arnedo, Izquierdo-Gascón, et al., 2022) Research on the Hungarian Krishna Valley, where followers of the Hare Krishna movement reside, reveals that religious influences shape ecological practices (Farkas, 2021). Similarly, African ethical systems, such as those proposed by Cheikh Anta Diop, emphasize communalism and sustainability, impacting ecological practices (Verharen, Bugarin, et al., 2021). The need for infrastructure development suggests that prioritizing affordable infrastructure and utilizing local financial resources can support sustainable expansion without compromising community values (Temesgen, 2020). Moreover, a comprehensive approach to healthcare service is essential for community well-being (Solhi, Zahed, et al., 2022).

In summary, ecovillages act as experimental platforms for rural development by integrating localized sustainability practices, alternative lifestyles, and strong community engagement. Case studies highlight the importance of policy support, cultural identity, and resident participation in addressing rural challenges such as infrastructure, healthcare, and economic resilience (Kodge, 2025; Tantiwatthanaphanich and Zou, 2016). Collectively, these studies suggest that ecovillages contribute to the achievement of the SDGs by offering adaptable, place-based models of sustainable living that are responsive to diverse social, political, and ecological contexts.

Theme 2: Educational approaches and learningEducational approaches in ecovillages encompass a variety of methodologies aimed at promoting sustainability, personal transformation, and community cohesion (Figure 8).

Esteves (2020) explores the intersection of peace education and regenerative ecology within the context of the Anthropocene, a geological epoch characterized by significant human impact on Earth. Esteves presents a case study of Tamera, an ecovillage in Portugal. Findings reveal that while ecovillages like Tamera face challenges in replicating their models due to local resistance and internal conflicts, successful diffusion requires balancing local embeddedness with transnational connections. The educational framework in ecovillages combines experiential learning and community-building activities, fostering collaborative and non-violent interactions between humans and nature. Esteves concludes that integrating peace education with regenerative practices in ecovillages can effectively address the challenges of the Anthropocene by promoting sustainable and peaceful ways of living (Esteves, 2020). In the same year, Pisters, Vihinen, et al. (2020) examine how personal transformation and sustainability intersect within ecovillage communities. Utilizing place-based transformative learning, the study analyses narratives from eco-villagers in Finland and Portugal. The findings highlight the significance of deep connections to place, community, and nature in fostering ecological consciousness and sustainable practices. The study identifies three key aspects of transformative learning: connection to place, compassionate relationships, and creative practices. These aspects drive personal and collective sustainability efforts by promoting critical reflection and innovative approaches to living sustainably (Pisters, Vihinen, et al., 2023). Pisters, Vihinen, et al. (2023) explores the role of ecovillages in fostering place-based transformative learning (PBTL). The study analyzes narratives from eco-villagers, highlighting how deep connections to place and community drive ecological consciousness and sustainable practices. Key aspects of PBTL identified include a connection to the environment, compassionate relationships, and creative, transgressive practices. These elements encourage critical reflection and innovative approaches to sustainability (Pisters, Vihinen, et al., 2023).

Other scholars have discussed the educational systems of ecovillages from three perspectives: Cisek and Jaglarz (2021) highlight the integration of deep ecology and sustainability principles into architectural education, emphasizing bioregional development and the Norwegian friluftsliv tradition. Their study underscores the importance of holistic and interdisciplinary approaches in fostering responsible design practices that harmonize with nature and effectively address ecological crises (Cisek and Jaglarz, 2021). Macintyre, Chaves, et al. (2020) explored the integration of higher education with community-based learning to tackle sustainability challenges. They present the Koru educational approach, which combines informal community learning with formal higher education through transgressive action research, as applied in a responsible tourism course in Colombia, highlighting the use of information and communication technologies, place-based learning, and intercultural communication as levers. However, power dynamics among participants posed barriers, emphasizing the need to address these dynamics and foster genuine transgressive learning processes (Macintyre, Chaves, et al., 2020). Pinto and Vilaça (2023) underscore the importance of understanding spiritual dimensions as part of broader social and environmental movements aiming for sustainability.

In conclusion, educational approaches in ecovillages emphasize place-based transformative learning, where deep connections to place, community, and nature foster ecological consciousness and sustainable behavior. These approaches integrate experiential and non-formal methods, such as peace education, spiritual reflection, and hands-on learning, promoting personal growth and non-violent, collaborative practices. Studies also highlight the importance of interdisciplinary and transgressive pedagogies that combine community-based learning with formal education to address complex socio-ecological challenges. Overall, ecovillage education cultivates locally rooted change-makers and offers context-sensitive strategies that directly support the achievement of sustainability goals.

Theme 3: Social practices and innovative economic practicesThe theme of Social Practices and Innovative Economic Practices is prominently represented in the research articles (Figure 9).

From the perspective of social practices, several studies have explored how ecovillages foster grassroots innovations and community-led sustainability transitions. Roysen, Bruehwiler, et al. introduce a new embedding framework to rethink the diffusion of grassroots innovations to address the limitations in current research. Grassroots innovations emerge from the bottom up through community action. The main driver for their emergence is not profit but social needs and ideology. This research identifies five key dynamics through the embedding framework: expansion, reframing, circulation of knowledge, shifting material arrangements, and replication. Through case studies of ecovillages in the Global North and South, demonstrates how these dynamics embed grassroots innovations in broader societal contexts (Roysen, Bruehwiler, et al., 2024). Similarly, Henfrey, Feola, et al. (2023) highlight the transformative potential of community-led initiatives in reshaping approaches to the SDGs, highlighting how grassroots innovations and local knowledge can offer alternative pathways to sustainability (Henfrey, Feola, et al., 2023). The paper "Resilient Utopias" explores how alternative approaches can address contemporary socio-economic challenges. It investigates the resilience of intentional communities, using Auroville, India, as a case study. The study aims to understand the factors that enable some intentional communities to thrive despite disturbances. It identifies general resilience factors, such as diversity, reserves, modularity, nestedness, openness, leadership, and trust, alongside emergent factors specific to Auroville, including unity of purpose, a creative mindset, and spiritual capital. These elements contribute to Auroville's ability to maintain its identity and function over time (Baumber, Le Hunte, et al., 2022). Further, ecovillages engage in social practices aimed at achieving autonomy and self-sufficiency through the localized management of basic resources (Skrzypczyński, 2021). Driven by the desire for a simple, self-sufficient lifestyle, these communities emphasize "convivial innovation", Bobulescu and Fritscheova (2021) introduce this concept, derived from Illich's "tools for conviviality," as a process of creating adaptable, accessible, and locally available innovations driven by the needs of the community rather than market forces (Bobulescu and Fritscheova, 2021). Wiest, Gamarra Scavone, et al. (2022) also point to the broader environmental implications of ecovillage lifestyles. Their findings suggest that adopting the sustainable living practices typical of ecovillages could contribute significantly to Europe’s decarbonization targets by 2050, with the potential to reduce per capita greenhouse gas emissions by up to 40% compared to the standard European lifestyle (Wiest, Gamarra Scavone, et al., 2022).

In addition, fostering a strong sense of community identity through social practices can significantly enhance the effectiveness of ecovillage sustainability programs (Ulug, Horlings, et al., 2021). Beyond the practices mentioned above, ecovillages create unique cultural dynamics that blend individual and collective experiences, promoting both personal and communal development (Szabó, Prohászka, et al., 2021). This revival of complex cultural practices reflects a broader trend of valuing intangible cultural heritage, highlighting the ecological and cultural sustainability goals of ecovillage communities (Farkas, 2023). Moreover, participation in ecovillage social practices can awaken participants' sense of security and positive memories (Poulsen, Pálsdóttir, et al., 2020).

From the perspective of economic practices. Olea Morris's paper focusing on how these communities redefine "rentabilidad" (profitability) beyond economic terms to include ecological dimensions. By studying Mexican ecovillages Aldea Ceiba and Rancho Bosque, Morris highlights how these communities manage relationships with more-than-human beings, synchronize activities with ecological cycles, and prioritize sustainable, self-sufficient lifestyles. The research argues that ecovillages, as "exilic spaces," provide valuable insights into alternative models of sustainability by challenging conventional profit maximization and promoting integrated, holistic practices that respect both human and ecological well-being. This includes the assumption that markets are inherently driven by profitable growth and that economic vitality is a necessary precondition for increasing living standards and fostering social improvements (Morris, 2022). Price, Ville, et al. explore the points of convergence between the modern market economy and diverse economies through the analysis of an Australian ecovillage's economic practices. The authors propose a framework that encompasses four key areas: economic production practices, attitudes towards growth, environmental responsiveness, and social relations. Through surveys and interviews with ecovillage members, the research reveals how these communities interact with the modern market economy while pursuing sustainable development. The paper emphasizes that ecovillages serve as experimental grounds where economic and ecological integration can be achieved without fully adopting capitalist models. The practices of these communities provide valuable insights into understanding how diverse economies operate within the context of the modern market economy and lay the foundation for future research (Price, Ville, et al., 2020). The article by Lennon and Berg (2022) investigates the evolution of ecovillage discourses from being perceived as countercultural and alternative to more mainstream and entrepreneurial. Through an analysis of media representations of the Hurdal ecovillage in Norway, the study reveals how ecovillages, initially viewed as idealistic and utopian, have shifted towards a narrative of commercial viability and integration with broader societal norms. This change reflects broader societal trends and policy frameworks emphasizing sustainability within the context of economic growth. The research highlights how media representations influence public perceptions of rural sustainable lifestyles and contribute to the construction of new rural identities, blending urban and rural elements into a modern 'eco-idyll' (Lennon and Berg, 2022). Moreover, Fiebrig, Zikeli, et al. explore the potential and realities of applying permaculture in commercial farming, comparing its differences with organic agriculture. The authors suggest that permaculture can be combined with organic farming to enhance the sustainability and resilience of agricultural systems (Fiebrig, Zikeli, et al., 2020).

The theme of “Social Practices and Innovative Economic Practices” highlights how ecovillages respond to contemporary sustainability challenges through community-led actions. Studies on social practices emphasize the roles of grassroots innovation, community identity formation, cultural revitalization, and educational engagement in enhancing the sustainability of ecovillages. In parallel, research on economic practices reveals how ecovillages reconstruct notions of profitability, develop diverse economies, and promote ecological–economic integration, offering practical foundations for alternative sustainability pathways. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that ecovillages function not only as experimental living communities but also as expanding platforms for social innovation within the global sustainability agenda, advancing goals rooted in ecological justice, cultural inclusion, and economic resilience.

Theme 4: Sustainability models and practicesThe diagram outlines a network of studies focused on sustainability models and practices within ecovillages. Central to this network are various key studies (Figure 10).

Mohseni and Brent, (2023) presents a probabilistic approach to optimizing hybrid battery and super-capacitor energy storage systems in micro-grids, emphasizing their financial and operational benefits for ecovillages. Copeland, MacKerron, et al. (2023) explore the challenges of achieving net-zero emissions in the Findhorn Ecovillage, using participatory methods to develop energy scenarios and highlighting the community's dependency on broader societal and economic systems (Copeland, MacKerron, et al., 2023). Colby and Whitley (2022) investigate the motivations behind participation in Earthship Biotecture, an off-grid architectural practice and social movement, underscoring the personal and environmental crises driving individuals towards sustainable living alternatives (Colby and Whitley, 2022). Sannidhi, Mandla et al. (2020) analyse the potential of integrated hybrid renewable energy systems, focusing on rice husk and solar energy to create sustainable power solutions for rural areas in India. Szabó, Prohászka, et al. (2021) examine the barriers and enablers of energy systems in ecovillages, stressing the importance of overcoming infrastructural and regulatory challenges to enhance sustainability. Syamsiyah, Sulistyowati, et al. (2023) assess the sustainability level of an ecovillage in West Java, Indonesia, highlighting the need for comprehensive evaluation metrics to ensure long-term ecological balance.

Theme 4 reflects the growing technical and systemic complexity of achieving ecological balance within ecovillage contexts. Studies in this area explore diverse strategies, including the optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems, the integration of off-grid architectural models, and the development of participatory frameworks for low-carbon transitions. These works emphasize the importance of technological innovation and context-specific evaluation tools in advancing sustainability.

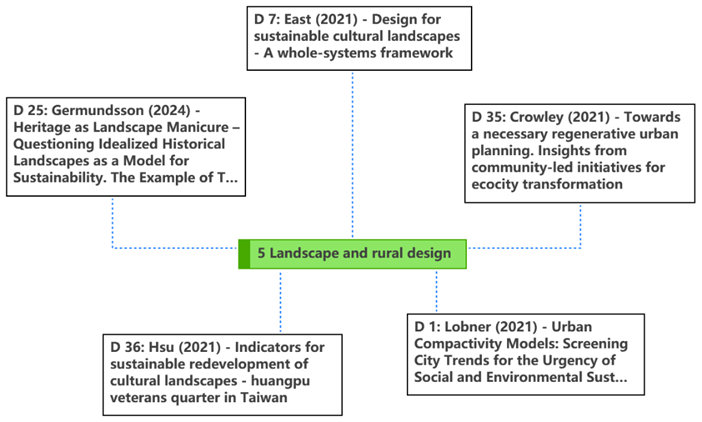

Theme 5: Landscape and rural designResearchers on this topic have explored the importance and challenges of design models in ecovillages for sustainable development (Figure 11). The study by Hsu, Chao, et al. (2021) identifies key impact factors for the redevelopment of the Huangpu Veterans Quarter in Taiwan through expert surveys, emphasizing the importance of preserving cultural values, historical sites, and maintenance management (Hsu, Chao, et al., 2021). Germundsson and Sanglert (2024) critique the use of idealized historical landscapes as a model for sustainability in the Toarp Ecovillage in Sweden, arguing that such aestheticization can obscure the real processes that shaped these landscapes and highlighting the need for a critical approach to using history and cultural heritage in sustainability planning (Germundsson and Sanglert, 2024). East, Gibsone, et al. (2021) propose a whole-systems framework for designing sustainable cultural landscapes, integrating cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioral learning outcomes, and stressing the importance of ecological, social, and cultural interdependencies. Together, these studies demonstrate that in the landscape design of ecovillages, the integrated consideration of historical, cultural, and social factors is crucial for achieving genuine sustainability (East, Gibsone, et al., 2021).

Moreover, Crowley, Marat-Mendes, et al. delve into regenerative urban planning, emphasizing the significance of community-led initiatives for transforming cities into sustainable ecocities and highlighting the role of community-led initiatives in urban settings, similar to the bottom-up, participatory approaches seen in ecovillages (Crowley, Marat-Mendes, et al., 2021). Lobner, Seixas, et al. explore urban compactness models, including eco-villages, as one of the sustainable urban development strategies. It discusses how ecovillages serve as a model for compact, resource-efficient, and socially inclusive communities, providing insights into how these principles can be applied to broader urban planning to mitigate urban sprawl and enhance environmental sustainability (Lobner, Seixas, et al., 2021).

Taken together, studies under Theme 5 highlight that design models in ecovillages play a vital role in mediating between ecological goals and cultural (Forero, Llano, et al., 2025), historical, and social contexts. The importance of such models lies in their capacity to integrate sustainability with place-based identity, heritage preservation, and community participation. At the same time, the challenges stem from risks of aestheticizing history, overlooking local dynamics, and the difficulty of applying context-sensitive frameworks in broader urban or institutional planning. These insights suggest that truly sustainable design in ecovillages must critically engage with both tangible and intangible layers of landscape and prioritize participatory, adaptive approaches.

This review paper focuses on the patterns and trends in ecovillages over the last five years. The results of the data analysis address the research question concerning the common factors through which ecovillages contribute to achieving the SDGs discussed in publications from 2020 to 2024. A total of 118 articles were initially identified, of which 53 were selected for in-depth analysis. The review employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating both quantitative and qualitative techniques.

The quantitative section presents data extracted from ATLAS.ti 23 visualizations and identifies five major themes in ecovillage research from 2020 to 2024: Rural Development, Educational Approaches and Learning, Social Practices and Innovative Economic Practices, Sustainability Models and Practices, and Landscape and Rural Design. Among these, Social and Economic Practices emerged as the most frequently addressed theme, while spatial and design-oriented topics gained increasing prominence after 2021. The reviewed literature spans 60 countries, with Portugal receiving the most attention. However, regions such as Africa and Southeast Asia remain significantly underrepresented. The word cloud analysis further underscores core concepts such as sustainability, community, and education, highlighting the multidimensional role of ecovillages in advancing the SDGs.

In the qualitative review, this study found that ecovillages function as dynamic laboratories for rural development. Theme 1 highlights their role in addressing rural challenges through localized sustainability practices, policy support, and strong community participation, contributing to more resilient and inclusive development models. Theme 2 reveals that educational approaches in ecovillages emphasize place-based transformative learning, integrating experiential, spiritual, and non-formal methods to cultivate ecological awareness and grassroots change-makers. Theme 3 demonstrates how ecovillages foster social innovation by advancing grassroots initiatives, reconfiguring economic practices, and promoting cultural regeneration. Theme 4 reflects the increasing technical complexity of sustainability, where ecovillages serve as testbeds for renewable energy systems and participatory low-carbon transitions. Lastly, Theme 5 underscores the importance of landscape and design strategies that integrate ecological goals with cultural, historical, and social dimensions, while also acknowledging challenges related to aestheticization and scalability.

Together, the quantitative and qualitative findings underscore the critical role of ecovillages in advancing the SDGs, not only as experimental models of sustainable living but also as adaptable, place-based frameworks for inclusive and context-responsive development. Their bottom-up nature challenges conventional top-down sustainability planning by centering community participation, local knowledge, and decentralized decision-making. This highlights the policy relevance of ecovillages as catalysts for grassroots innovation, underscoring the importance of adaptive governance frameworks that support community autonomy, accommodate diverse socio-ecological contexts, and facilitate the long-term institutional integration of ecovillage-based practices into broader development agendas.

However, despite the comprehensive discussion on ecovillages, several gaps have been identified for future research. Current discussions predominantly focus on the positive aspects of ecovillages in achieving SDGs while neglecting the potential drawbacks reflected in the dynamic laboratory function of ecovillages. Moreover, the integrated planning dimensions, particularly the interplay among spatial, institutional, and social systems, remain insufficiently addressed. As grassroots initiatives, ecovillages are also shaped by broader policy environments and evolving community formation processes, both of which warrant deeper empirical and theoretical examination.

Conceptualization, X.L.; methodology, X.L.; software, X.L.; investigation, X.L.; resources, X.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L., M.K.H., and M.S. M. N.; supervision, M.K.H.and M.S. M. N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

The authors would like to express their appreciation to those who provided valuable insights during the development of this review.