2025 Volume 72 Issue 4 Article ID: 7204201

2025 Volume 72 Issue 4 Article ID: 7204201

Metagenomics can be used to obtain sequence information on putative genes in a microbial community. However, it is difficult to identify genes with specific functions among the numerous predicted genes. In this study, we attempted to identify genes induced in cultured microbes by the addition of saccharides using metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses. A mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides was used as the inducer in this study. Some genes were highly induced in the presence of additive saccharides and formed gene clusters for the utilization of additive saccharides, suggesting that metatranscriptomic and metagenomic analyses are useful for analyzing carbohydrate-responsive genes in microbial communities and screening novel carbohydrate-active enzymes.

TPM, transcripts per million; GH, glycoside hydrolase

Metagenomics uses the total genomic DNA of microbes as a genetic resource [1]. Metagenomic approaches, including functional screening and genome mining of metagenomic DNA, have been used to screen for carbohydrate-active enzymes [2, 3, 4]. With the advancement of DNA sequencing technology and bioinformatics analyses, metagenomic approaches have been used in a variety of scientific fields, such as enzyme screening [5, 6] and environmental microbiology [7, 8]. It is difficult to identify genes that encode enzymes with specific functions, or those that play important roles in the environment from the vast amount of genetic information obtained by metagenomic analysis. Recently, metatranscriptomic approaches, which analyze the total mRNA of microbial communities, have been used in environmental microbiology to analyze the functions and interactions of microbes [9].

In this study, we used the microbial community of lotus cultivation water. Some leaves of the lotus decayed in the cultivation water, and it was speculated that microbes that degraded plant polysaccharides were present. Microbes of lotus cultivation water were inoculated into oligotrophic agar medium containing 50 mg/L peptone, 50 mg/L yeast extract, 50 mg/L casamino acids, 50 mg/L glucose, 50 mg/L soluble starch, 30 mg/L dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, 5 mg/L magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, 30 mg/L sodium pyruvate, and 20 g/L agar, and incubated at 20 °C for 17 days. Colonies of microbes on the oligotrophic agar medium were harvested by suspending the cells in a saccharide-free oligotrophic liquid medium containing 50 mg/L peptone, 50 mg/L yeast extract, 50 mg/L casamino acids, and 30 mg/L dipotassium hydrogen phosphate. The microbes in the saccharide-free oligotrophic liquid medium were dispensed into three tubes, and metagenomic DNA was extracted from one tube using the Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research Corporation, Orange, CA, USA) (Fig. 1). The other two tubes were incubated at 20 °C at 80 rpm for 3 h in the presence or absence of mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides prepared as described in the Experimental section. As both polysaccharides and oligosaccharides induce the expression of plant polysaccharide degradation-related enzymes in microbes [10], we partially degraded arabinoxylan in advance using endo-1,4-β-xylanases from Aspergillus oryzae. After incubation, total RNA was extracted using an AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). A sequencing library of the extracted metagenomic DNA was constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). The constructed metagenomic DNA library was sequenced using an Illumina, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA) NovaSeq X Plus sequencer (150 bp × 2 paired-end). The extracted total RNA from the microbes was treated with the Ribo-off rRNA Depletion Kit V2 (Bacteria) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) to remove ribosomal RNA. A sequencing library was constructed using the MGIEasy Fast RNA Library Prep Set (MGI Tech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and sequenced using DNBSEQ-T7 (MGI Tech Co., Ltd.) (150 bp × 2 paired-end).

CDS, coding DNA sequence.

Metagenomic reads were first subjected to adapter trimming and quality control using fastp v0.24.0 [11]. Taxonomic profiling was performed using Kraken2 v2.1.3 [12] for initial classification and Bracken v3.0.1 [13] for abundance estimation. Prokaryotic reads were classified to estimate the taxonomic abundance at the family, genus, and species levels. High-quality reads were assembled into contigs using MEGAHIT v1.2.9 [14] with default parameters, and contigs of 3,000 bp or longer were retained for downstream analyses. Protein-coding genes were predicted from contigs using Prodigal v2.6.3 [15] in metagenomic mode. The predicted proteins were functionally annotated using dbCAN v4.1.4 [16], which identifies carbohydrate-active enzymes based on hidden Markov model profiles.

Metatranscriptomic reads were processed using fastp for adapter removal and quality control. Ribosomal RNA reads were removed using SortMeRNA v4.3.7 [17]. The remaining reads were mapped to metagenomic contigs using Bowtie2 v2.5.4 [18] with the “very-sensitive” option. Gene-level expression was quantified using featureCounts v2.0.6 [19] in paired-end mode, with option “-P -C -B”, which ensured that only properly-paired, concordantly-mapped read pairs on the same contig and strand were counted. Transcript abundance was reported as transcripts per million (TPM) based on gene length and total mapped reads per sample.

Metagenomic sequencing generated 23.7 × 106 paired-end reads, of which over 95 % passed quality control. These reads were assembled into 320,763 contigs (≥ 200 bp), totaling 330 Mbp with an N50 of 1,506 bp. Of these, 11,081 contigs longer than 3,000 bp were retained for downstream analysis, with a total length of 126 Mbp. From these contigs, 120,499 genes were predicted with an average length of 936 bp. Metatranscriptomic sequencing produced approximately 25.0 × 106 paired-end reads per sample, with more than 95 % retention after quality control and rRNA removal. The mapping rate of the metagenomic contigs was approximately 76 % in both samples. The proportion of concordantly-mapped read pairs (uniquely aligned, excluding multi-mapped reads) was 47 % and 48 % in the absence and presence of saccharides, respectively. FeatureCounts identified 34.2 × 106 and 33.2 × 106 alignments in the absence and presence of additive saccharides, respectively, of which 30.2 % and 29.6 % were successfully assigned to genes.

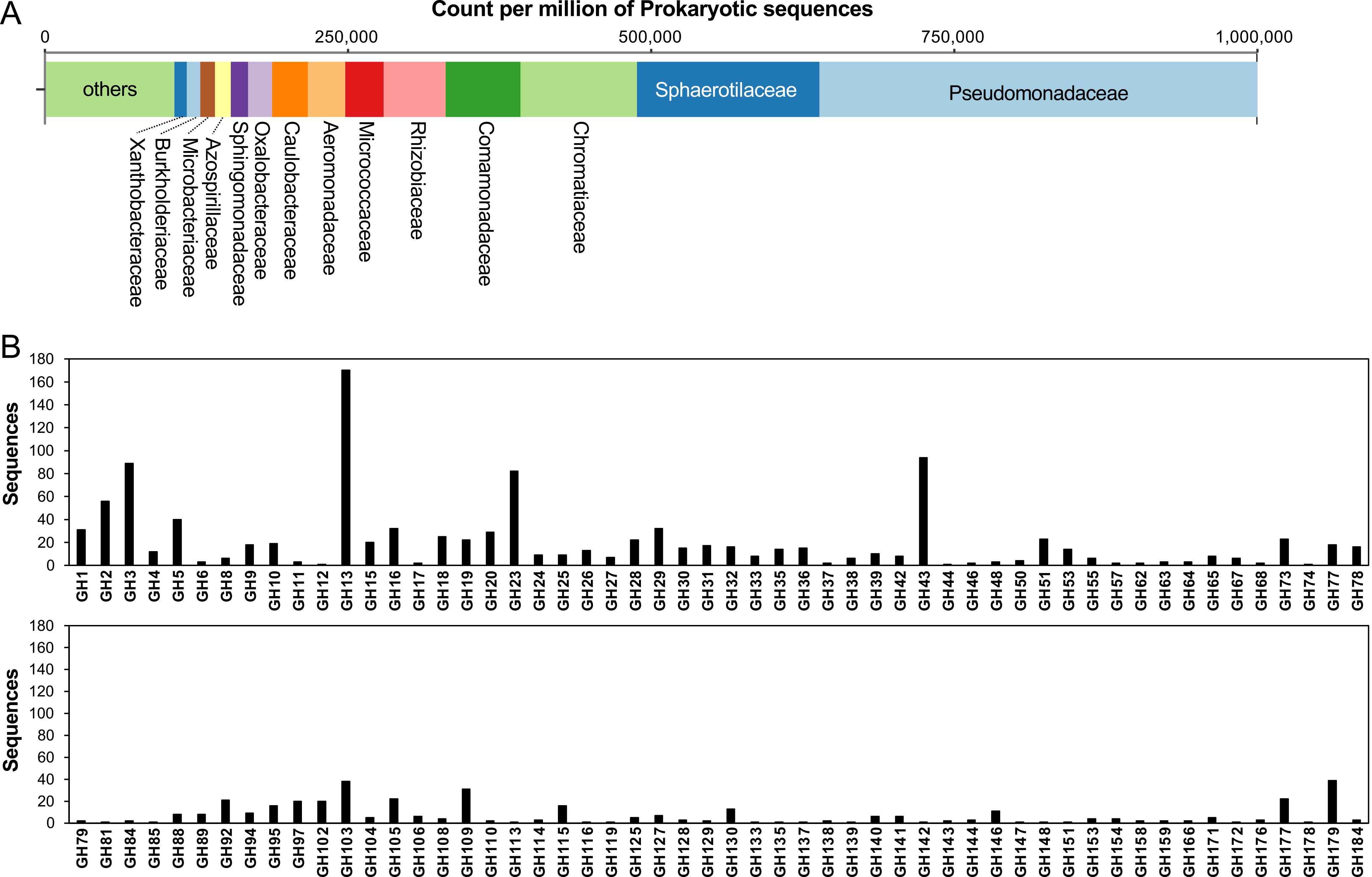

The bacterial flora in the saccharide-free oligotrophic liquid medium is shown in Fig. 2A. The microbiota in the saccharide-free oligotrophic liquid medium consisted of Pseudomonadaceae, Sphaerotilaceae, Chromatiaceae, Comamonadaceae, Rhizobiaceae, and other bacteria (Fig. 2A). Of the 120,499 genes predicted using metagenomic analysis of the microbiota, 1,482 glycoside hydrolases (GHs), 188 auxiliary activities, 280 carbohydrate esterases, and 83 polysaccharide lyases were identified. Of these, GH13 was the most abundant (Fig. 2B). In addition, many GH1, 2, 3, 5, 16, 23, 29, 43, 103, 109, and 179 enzymes were found. However, some GHs, including GH7, 14, 22, 34, 45, 47, 49, 52, and 54 were not found in our metagenomic analysis. In our experiments, the microbes were cultured using an oligotrophic agar plate medium containing low concentrations of soluble starch and glucose, which may have biased the microbiota and their GHs. It is presumed that the composition of the microbes can be altered by changing the composition of the media and environmental samples used for inoculation.

Metatranscriptomic analysis indicated that several genes were highly expressed in the presence of a mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides. For example, 19 genes encoding GH10 were identified using metagenomic analysis. Although many GH10 enzymes contain only the GH10 catalytic domain, some GH10 enzymes contain carbohydrate-binding module(s) (Fig. 3A). Of the genes encoding GH10 enzymes, some genes, including contig-149924_gene-180, contig-305325_gene-38, contig-324556_gene-2, and contig-25985_gene-29, were induced in the presence of a mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides (Fig. 3B). In particular, contig-149924_gene-180 was highly expressed in the presence of a mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides. The GH10 enzyme encoded by contig-149924_gene-180 showed similarity to the endo-1,4-β-xylanase of Bacteroides ovatus (identity 47.8 %) [20] and putative GH10 xylanases of Rheinheimera species. TPM values were closely related to the number of cells in the microbial community (Fig. 2A). Thus, the TPM values of the genes of dominant microbes tended to be higher than those of minor microbes.

SP, signal peptide.

Next, we focused on the genes located near the gene locus of the highly-induced GH10, contig-149924_gene-180. The gene locus of gene-180 in contig-149924 was located near the loci encoding putative GHs (gene-171, GH9; gene-174, GH115; gene-175 and -184, GH43; gene-185 and -186, GH3), putative pentose metabolism related enzymes (gene-172, transketolase; gene-173, transaldolase; gene-177, xylose kinase; gene-178, xylose isomerase; gene-181, aldose epimerase), putative sugar transport system (gene-182, sugar porter family MFS transporter; gene-183, glycoside/cation symporter) and putative xylose operon regulatory protein (gene-176) (Fig. 4A). Based on the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) [21], the amino acid sequences of these proteins were similar to those of uncharacterized proteins of Rheinheimera species (86-98 % identity), such as R. mangrovi isolated from mangrove sediment [22], suggesting that contig-149924 came from Rheinheimera species (Chromatiaceae). The amino acid sequences of gene-171 (GH9), gene-174 (GH115), gene-175 (GH43 subfamily 12, GH43_12), gene-184 (GH43 subfamily 1, GH43_1), gene-185 (GH3), and gene-186 (GH3) were similar to those of GH9 xyloglucan-specific endo-β-1,4-glucanase of Bacteroides ovatus (identity 41.5 %) [23], GH115 xylan α-1,2-glucuronidase of Streptomyces pristinaespiralis (identity 40.0 %) [24], GH43 bifunctional β-xylosidase/α-L-arabinofuranosidase of Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens (identity 36.9 %) [25], GH43 β-xylosidase of Mycothermus thermophilus (identity 65.7 %) [26], GH3 oligo-ulvan β-xylosidase of Formosa agariphila (identity 40.2 %) [27], and GH3 β-glucosidase of Bacteroides ovatus (identity 29.3 %) [23], respectively. Except for gene-179, the expression of genes located near the locus of gene-180 was induced in the presence of a mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides (Fig. 4B). In particular, the expression of gene-177, encoding a putative xylose kinase; gene-178, encoding a putative xylose isomerase; and gene-183, encoding a putative glycoside/cation symporter, was more than 80-fold higher in the presence of a mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides (Fig. 4B).

GH9 (gene-171), GH115 (gene-174), GH43_12 (gene-175), GH10 (gene-180), and two GH3s (gene-185 and gene-186) contained a putative N-terminal signal peptide for secretion (SignalP; https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-6.0/). These results suggest that xylans, including arabinoxylan and glucuronoxylan, are degraded into oligosaccharides by a putative extracellular GH10 endo-1,4-β-xylanase (gene-180). Side chain residues, such as α-(1→2)- and α-(1→3)-linked L-arabinofuranose and α-(1→2)-linked 4-O-methyl-glucuronic acid, of oligosaccharides are released by putative GH43 bifunctional β-xylosidase/α-L-arabinofuranosidase(s) (gene-175 and/or gene-184) and putative GH115 α-1,2-glucuronidase (gene-174), respectively. The produced xylooligosaccharides are degraded into xylose by putative GH43 bifunctional β-xylosidase/α-L-arabinofuranosidase(s) (gene-175 and/or gene-184) and/or putative GH3 β-xylosidase (gene-185), which are then taken up by the cells and metabolized.

The contig-149924 (395,375 bp) was composed of 328 genes. This gene cluster was located in the middle of contig-149924 (Fig. 4C). The expression of genes around this gene cluster and several other genes was induced by a mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides. However, many genes in this contig-149924 were not induced (Fig. 4C).

In addition to the GHs described above, other putative carbohydrate-active enzymes, including some of the GH3, GH30, GH35, GH42, GH43, GH51, GH53, GH95, and auxiliary activity family 3 enzymes, were induced in the presence of mixture of arabinoxylan and its derived oligosaccharides in the microbial community (data not shown). Recently, Serrano-Gamboa et al. identified some carbohydrate-active enzymes using metatranscriptome profiling of microbial consortia that degrade maize pericarp [28], and Prattico et al. identified GH32 enzymes using metatranscriptomic and metagenomic analyses of a human stool samples as microbial communities and fructo-oligosaccharide as an inducer of carbohydrate-active enzymes [29]. Metatranscriptomic analyses can elucidate different genes, depending on the inducer, even within the same microbial community. The cooperative and synergistic actions of multiple enzymes are important for the degradation of polysaccharides [23, 30]. By combining metatranscriptomic and metagenomic analyses, it is possible to clarify the gene loci and cooperative actions of enzymes involved in polysaccharide degradation.

A mixture of arabinoxylan and the derived oligosaccharides was prepared as follows. Genes encoding GH10 and GH11 xylanases (XynF1 and XynG1, respectively) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction using complementary DNA prepared from total RNA of A. oryzae as reported previously [31] and primers (5′-AACTATTTCGAAACGATGGTACACCTTAAGGCACTTGC-3′ and 5′-ATGATGATGGTCGACCAGAGCATCGATGATAGCATTATACGC-3′ for xynF1; 5′-AACTATTTCGAAACGATGGTTAGCTTCTCTTCTCTCCTCC-3′ and 5′-ATGATGATGGTCGACCTCAACAGTGATAGTGGCAGACCC-3′ for xynG1). Amplified DNA fragments were connected to pGAPZ A and introduced into the methylotrophic yeast, Pichia pastoris X-33, as previously reported [32]. His6-tagged XynF1 and XynG1 were heterologously expressed as previously described [33] and purified using a Ni2+ affinity column (His60 Ni Superflow Resin, Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) as previously described [34]. Wheat flour arabinoxylan was purchased from Megazyme Ltd. (Wicklow, Ireland) and was dissolved in water. XynF1 (3.6 μg) and XynG1 (4.8 μg) were added to 5.2 mL of 5 mg/mL arabinoxylan solution and incubated at 37 °C for approximately 16 h. The reaction mixture was then boiled to stop the reaction.

The DNA sequences of genes described in this study were deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers LC876930-LC876963.

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

We thank Dr. Tomomi Sumida and Dr. Satoshi Hiraoka (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology) and Dr. Yuya Sato and Dr. Yusuke Nakamichi (National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology) for the helpful discussions. We thank Keita Tomiyoshi (Kagawa University) for the cultivation of lotus. We thank Hirokazu Kato and the Gene Research Center (Kagawa University) for their technical expertise. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. This study was supported by the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka (IFO).