2013 年 63 巻 2 号 p. 197-204

2013 年 63 巻 2 号 p. 197-204

Cold temperature during the reproductive phase leads to seed sterility, which reduces yield and decreases the grain quality of rice. The fertilization stage, ranging from pollen maturation to the completion of fertilization, is sensitive to unsuitable temperature. Improving cold tolerance at the fertilization stage (CTF) is an important objective of rice breeding program in cold temperature areas. In this study, we characterized fertilization behavior under cold temperature to define the phenotype of CTF and identified quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for CTF. A wide variation in CTF levels has been identified among local cultivars in Hokkaido, which is one of the most northern regions for rice cultivation in the world. Clear varietal differences in pollen germination, and pollen tube elongation due to cold temperature have been observed. These differences may confer a degree of CTF among this population. We conducted QTL analysis for CTF using 120 backcrossed inbred lines derived from a cross between Eikei88223 (vigorous CTF) and Suisei (very weak CTF). Three QTLs for CTF were identified. A clear effect by QTL, qCTF7, for increasing the level of CTF was validated using advanced progeny. These results will facilitate marker-assist selection for desirable QTLs for CTF in rice breeding program.

Temperature conditions place a major limit on plant productivity. Excessively hot or cold temperature conditions cause physiological disorders in plant development, which result in yield reductions. Continuous improvements in the tolerance of plants to unsuitable temperature in plant breeding programs have been performed using various strategies that have successfully produced many beneficial achievements (Sanghera et al. 2011, Wahid et al. 2007). However, unsuitable temperature stress still periodically decreases plant productivity. Furthermore, current speculation about climate change suggests that most agricultural regions will experience more extreme environmental fluctuations (Solomon et al. 2007). In addition, plants are now cultivated in new regions with different climatic fluctuations to supply the increasing demand on agricultural production such as crops and bioenergy. Improvements in the tolerance to unsuitable temperature conditions will become a more important objective in plant breeding programs.

Rice, Oriza sativa L., is one of the most important staple crops in the world and originated in a tropical region. Nearly half of the world’s population depends on rice. Cold temperature is one of the major constraints of rice production in high latitude or high altitude areas in the world. Even though cold temperature affect rice growth from seed germination to seed maturity, episodes of cold temperature at the reproductive phase decrease the seed set.

Two stages of the reproductive phase in rice are known to be the most sensitive to cold temperature: the booting stage (Satake and Hayase 1970) and fertilization stage (Satake and Koike 1983). At the booting stage, ranging from pre-meiotic mother cells to microspores and pollen maturation, cold temperature can disrupt mitosis I and II, which prevents rice microspores from maturing into normal tricellular pollen grains (Satake and Hayase 1970). The fertilization stage begins just after pollen maturation and the complete fertilization stage consists of anther dehiscence, pollen germination, pollen tube elongation and fertilization. Because these occur during a short window of time, little is known about the phenotype of seed sterility under cold temperature at the fertilization stage in rice.

Cold tolerance at the booting stage (CTB) has been improved in rice breeding program. CTB is evaluated by seed fertility in the field using cold-water irrigation at 18–19°C from pre-meiotic mother cells until grain maturity. Using this method, large varietal differences and extensive QTLs for CTB have been identified (Kuroki et al. 2007, Mori et al. 2011, Saito et al. 1995). These QTLs may be useful for the introduction of higher CTB levels by marker-assist selection (MAS) in rice breeding program. On the other hand, evaluating cold tolerance at the fertilization stage (CTF) requires laborious work with controlled growth chambers to treat cold temperature at specific stages, without cold injury at the booting stage and a uniform heading time. Phenotypic variations and the genetic bases of CTF have not yet been clarified.

Vigorous CTF is the most important characteristic for a high percentage seed set under cold temperature in higher latitude or higher altitude areas. Identifying the number of genes and magnitude of their effects may contribute to a better understanding of the genetic control of CTF and facilitate the development of new cultivars with vigorous CTF. In this study, with the evaluation method for CTF established by the Kamikawa Agricultural Experiment Station (Tanno et al. 2000), we characterized fertilization behavior and identified the QTLs conferring CTF in rice. The results of this study will be useful for improving CTF in rice breeding program in areas with cold temperature.

Nineteen rice cultivars from Hokkaido were used to evaluate variations in CTF (Table 1). These cultivars were breeding lines established between 1983 and 2006 and were selected as those that have an important role on pedigree in rice breeding program in Hokkaido. During this period, no selection pressure was focused on CTF in rice breeding program.

| Cultivars | Breeding year | Cold temperature treatment | Controlled tempreature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of panicles | No. of spikelets | Seed fertility (%) | No. of panicles | No. of spikelets | Seed fertility (%) | ||

| Hoshimaru | 2006 | 11 | 272 | 92.6 ± 5.9 | 16 | 327 | 95.5 ± 4.8 |

| Hokkai302 | 2005 | 15 | 358 | 88.9 ± 7.6 | 16 | 375 | 98.1 ± 3.8 |

| Eikei88223 | 1988 | 12 | 364 | 87.8 ± 7.0 | 16 | 417 | 97.9 ± 3.6 |

| Shirokumamochi | 2007 | 10 | 313 | 82.0 ± 12.5 | 16 | 473 | 97.0 ± 2.5 |

| Kitaibuki | 1993 | 10 | 369 | 81.2 ± 11.2 | 16 | 239 | 98.4 ± 1.8 |

| Hokuikumochi87 | 1992 | 13 | 340 | 79.0 ± 13.0 | 16 | 432 | 96.8 ± 4.1 |

| Nanatsuboshi | 2001 | 9 | 224 | 78.4 ± 9.9 | 16 | 382 | 97.9 ± 3.6 |

| Hatsushizuku | 1998 | 11 | 283 | 75.3 ± 9.9 | 16 | 317 | 99.4 ± 1.7 |

| Hoshinoyume | 1996 | 15 | 413 | 75.3 ± 13.1 | 16 | 385 | 98.1 ± 3.1 |

| Kitaake | 1983 | 10 | 278 | 73.0 ± 11.1 | 16 | 452 | 98.4 ± 2.0 |

| Hakutyoumochi | 1988 | 19 | 531 | 68.9 ± 11.3 | 15 | 371 | 95.3 ± 8.2 |

| Jouiku455 | 2006 | 12 | 292 | 66.1 ± 9.9 | 16 | 377 | 98.9 ± 2.0 |

| Kirara397 | 1988 | 15 | 365 | 64.8 ± 20.1 | 16 | 442 | 98.9 ± 2.0 |

| AC99084 | 1999 | 9 | 245 | 62.4 ± 11.2 | 16 | 385 | 98.2 ± 2.6 |

| Kazenokomochi | 1995 | 16 | 479 | 48.2 ± 15.0 | 16 | 445 | 98.5 ± 1.7 |

| Ayahime | 2001 | 13 | 395 | 44.5 ± 23.1 | 15 | 371 | 95.3 ± 8.2 |

| Aya | 1992 | 7 | 152 | 32.8 ± 11.9 | 8 | 153 | 97.2 ± 4.8 |

| Ginnpu | 2000 | 14 | 426 | 11.6 ± 8.1 | 15 | 394 | 95.9 ± 11.1 |

| Suisei | 2006 | 12 | 317 | 7.5 ± 7.9 | 16 | 355 | 98.3 ± 2.4 |

Back crossed inbred lines (BILs) derived from the cross between Suisei (very weak CTF) and Eikei88223 (vigorous CTF) were developed as a mapping population. F1 plants between Suisei and Eikei88223 were backcrossed with Suisei to produce BC1F1 seeds. A total of 120 BC1F4 plants were developed by the single-seed descent method. One plant from each line was selected and leaf tissue was collected for the extraction of total DNA. The CTF of each line was evaluated for the self-pollinated seeds of selected plants.

A total of 77 BC1F5 plants derived from a single BIL, BIL107, in mapping population were used as advanced progeny to validate the most efficient QTL, qCTF7. In this population, the qCTF7 region was heterozygous, while the other two QTL regions were homozygous for Suisei.

Evaluation of CTFThe evaluation of CTF was carried out according to Tanno et al. (2000). For the mapping population and cultivars, sixteen germinated seeds were sown into a plastic pot (150 mm length, 500 mm width and 100 mm height) and grown in a greenhouse. After 30 days, eight plants with uniform growth were used for further experiments. Tillers except for the main culm were removed to ensure the uniform growth of the main culms. To avoid damage by cold temperature at the booting stage, 30-day-old plants were grown in a growth chamber of 26/20°C day/night under a natural sunlight intensity and day length until the start of the cold temperature treatment. For the cold temperature treatment, the pot was moved to a growth chamber of 17.5/17.5°C day/night with 50% shading of a natural sunlight intensity, when at least three plants in the pot headed (i.e. the appearance of the panicle from the sheath of the flag leaf); In each plant line or cultivar, 5–10 panicles were examined to evaluate CTF. After 15 days of the cold temperature treatment, plants were moved to and grown in a growth chamber of 26/20°C until the seed maturing stage. The percentage of seed fertility has been used as a parameter of cold tolerance. As a control, the seed fertility of plants in a growth chamber without the cold temperature treatment was examined.

To validate the effect of qCTF7 in the advanced progeny, one germinated seed was sown into a 500 ml plastic pot and grown in a greenhouse. When at least two panicles in a plant headed, the pots were moved to a growth chamber of 17.5/17.5°C. In each plant, 2–4 panicles were examined to evaluate CTF.

Pollen maturityTo evaluate pollen maturity, anthers were collected from a spikelet before flowering during the cold temperature treatment and placed on a glass slide. The anthers were crushed and stained with I2-KI (0.2% iodine and 2% potassium iodine) to evaluate pollen maturity using a light microscope. The pollen grains from 100–150 anthers of 5–6 panicles were examined. Pollen maturity in each anther was calculated based on the frequency of stainable pollen grains from 40–80 pollen grains counted. Anthers grown without the cold temperature treatment were used as the control.

Pollen germination on the stigma and pollen tube elongation in the styleSpikelets just beginning to flower during the cold temperature treatment were marked. The next day, pistils of the marked spikelets were sampled and fixed in EAA solution (100% ethanol : acetic acid = 3 : 1). For each cultivar, 20–30 pistils from 3–4 panicles were used. The treated pistils were softened in 1 N KOH for 15 min at 55°C using a block heater and were then washed in distilled water for a few minutes and stained with 0.1% aniline blue in K3PO4 buffer, pH 8.5, for 2 hours at room temperature. Samples were rinsed in distilled water and mounted in 50% glycerol. Pollen grains on the stigma were observed under a fluorescence microscope.

DNA analysisTotal DNA was extracted from the leaves of each plant using the CTAB method with modifications (Murray and Thompson 1980). Genotyping with SSR markers was performed as described by Fujino et al. (2004). To amplify genomic DNA to detect SSRs, we used 949 primer sets from the lists provided by McCouch et al. (2002) and IRGSP (2005). Eighty-seven SSR markers showing clear polymorphisms were used for the analysis of BILs (Supplemental Fig. 2). For the validation of qCTF7, eight SSR markers were used to determine the heterozygous chromosomal region of qCTF7 in advanced progeny. A total of 10 markers were used for QTL analysis of this population.

QTL analysisA linkage map was constructed using MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0 (http://www.broad.mit.edu/ftp/distribution/software/mapmaker3/). The detection of QTLs was conducted by composite interval mapping with QTL Cartographer 2.5 (http://statgen.nesu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLcart.htem). The threshold to detect QTLs was determined by the 1000 per-mutation test at a probability level of 0.05: LOD2.74. To normalize variance, the percentage of seed fertility was arc-sine-transformed and used for QTL analysis.

Seed fertility among the 19 cultivars was over 90% as a control, while large variations in seed fertility were observed with the cold temperature treatment. The mean value of seed fertility after the cold temperature treatment was 64.2%, ranging from 7.5% of Suisei to 92.6% of Hoshimaru, with continued distribution (Table 1). Selection for CTF has never been performed during rice breeding program in Hokkaido. No trends in the association of the degree of CTF with pedigree and breeding year were found in this CTF variation.

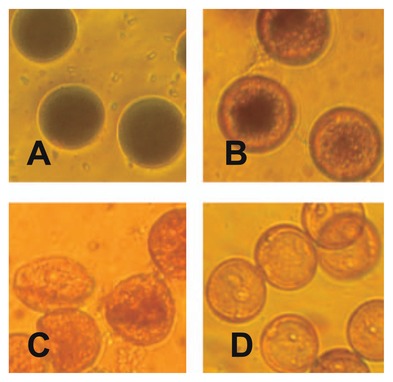

Pollen maturation and fertilization under the cold temperature treatmentWe selected Eikei88223 and Hoshinoyume as vigorous CTF cultivars, Ayahime as a weak CTF cultivar and Suisei as a very weak CTF cultivar to characterize morphological changes (including pollen maturity, pollen germination on the stigma and pollen tube elongation in the style) during the fertilization stage by the cold temperature treatment as varietal differences. The influence of the cold temperature treatment on pollen maturity at the fertilization stage was investigated with I2KI staining. Several types of pollen grains were observed in the anthers from spikelets before flowering at 3, 7, or 10 days after the start of the cold temperature treatment. Pollen grains staining black were defined as mature (Fig. 1A), while those staining red were defined as degraded (Fig. 1B). In this type of pollen grain, starch around the whole of the cell wall was degraded. Pollen grains staining red with an abnormal shape were defined as seriously degraded (Fig. 1C). Pollen grains without staining and a normal shape were defined as immature (Fig. 1D).

Light microscopic images of pollen grains stained with I2KI by the cold temperature treatment. A: mature pollen grains, B: degraded pollen grains, C: seriously degraded pollen grains, D: immature pollen grains.

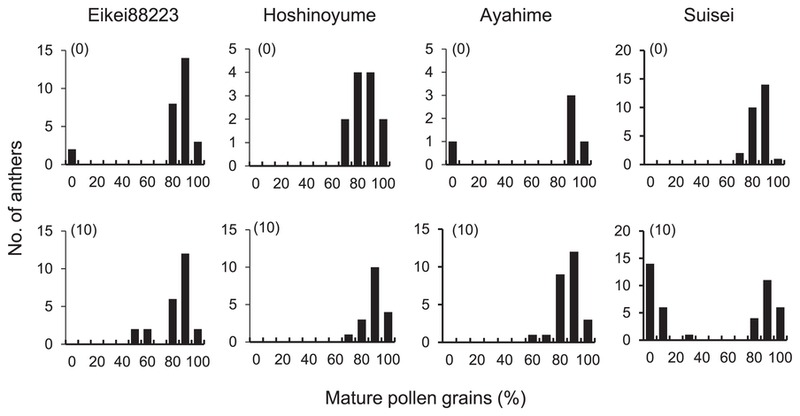

A clear difference in pollen maturation was observed (Fig. 2). The anthers of Eikei88223, Hoshinoyume and Ayahime showed a high percentage of mature pollen grains 10 days after the cold temperature treatment, similar to those before the cold treatment (0 days). On the other hand, although a high percentage of mature pollen grains was observed in Suisei before the cold treatment, the number of anthers showing a low percentage of mature pollen grains increased with the cold temperature treatment (Supplemental Fig. 1). After 10 days of the cold temperature treatment, about 50% of anthers included many degraded or seriously degraded pollen grains (Fig. 2). Unusual starch degradation may have occurred with the long cold temperature treatment.

Frequency distributions of anthers with the percentage of mature pollen grains after 0 or 10 days of the cold treatment. The number of days of the cold temperature treatment is shown in parentheses.

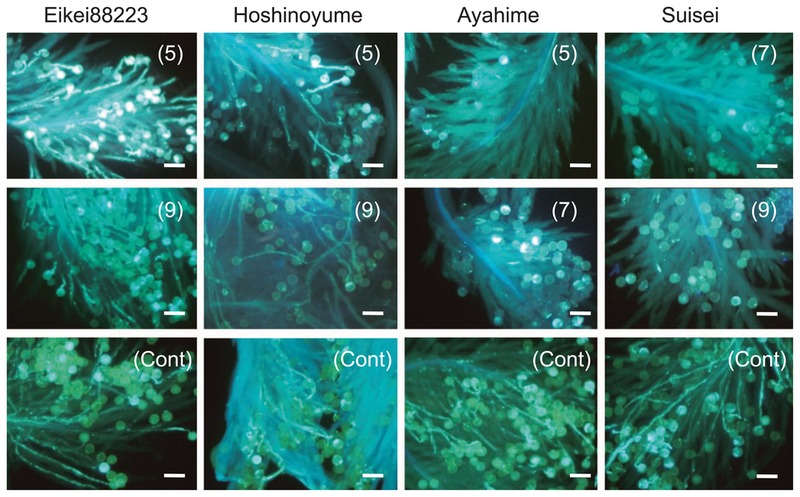

There was no difference in pollen germination and pollen tube elongation among the cultivars as controls. Due to the cold temperature treatment, the rate of pollen germination was markedly reduced in Ayahime and Suisei, which showed poor pollen tube elongation (Fig. 3). Pollen germination and vigorous pollen tube elongation were frequently observed in Eikei88223 and Hoshinoyume.

Variations in pollen germination on the stigma and pollen tube elongation in the style during the cold temperature treatment. The number of days of the cold temperature treatment is shown in parentheses. Cont means the controlled temperature condition. Scale bar = 100 μm.

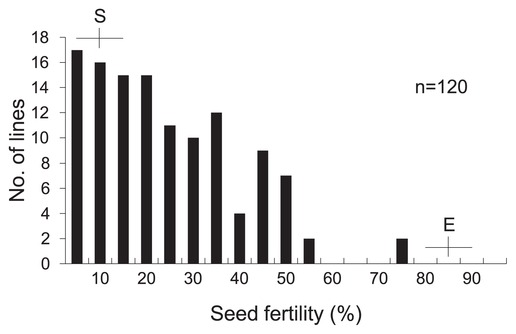

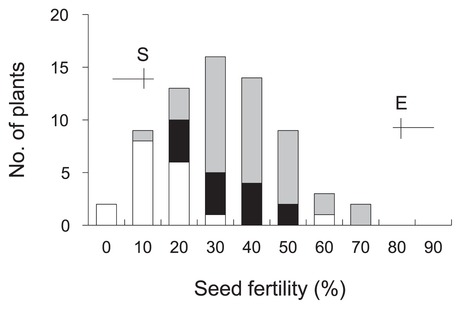

To identify QTLs for CTF, BILs derived from the cross between Eikei88223 (vigorous CTF) and Suisei (very weak CTF) were developed as mapping populations. A clear difference in CTF between Suisei and Eikei88223 was observed, 7.5% and 87.5%, respectively. Under field conditions, all lines of the mapping population showed high seed fertility, at more than 80%. However, after the cold temperature treatment, seed fertility among BILs showed continuous variations from 1.2% to 73.7%, with a mean of 22.0% (Fig. 4).

Frequency distributions of seed fertility by the cold temperature treatment in BC1F4 progeny derived from the cross of Suisei/Eikei88223//Suisei. Horizontal and vertical lines represent ranges and mean values for Eikei88223 (E) and Suisei (S), respectively.

A total of 949 SSR markers distributed throughout the genome were surveyed to detect polymorphisms between parents. Only 87 markers (9.2%) exhibited polymorphisms (Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 2). As the parents for BILs are local varieties from a single area, Hokkaido, they have a very close genetic relationship (Supplemental Fig. 3). Regions with no polymorphic markers may be genetically identical between parents.

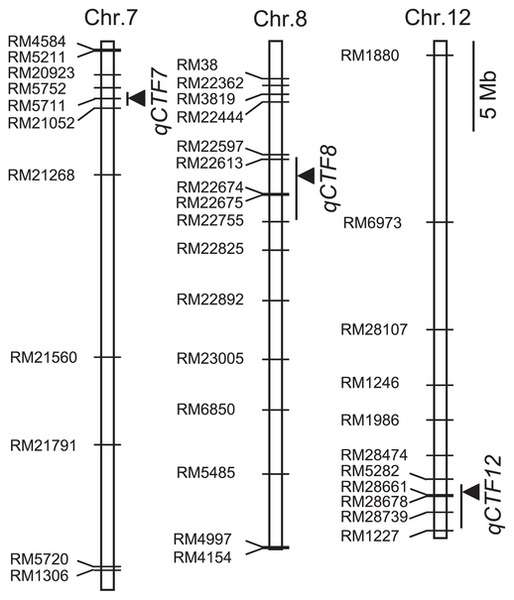

Three putative QTLs associated with CTF were detected (Fig. 5 and Table 2). The Eikei88223 alleles at all detected QTLs increased the degree of CTF. qCTF7 near RM5711 on chromosome 7 was the most effective, which explained 19.2% of the total phenotypic variation. qCTF12 near RM28661 on chromosome 12 and qCTF8 at the marker RM22613 on chromosome 8 accounted for 14.8 and 7.9% of the total phenotype variation, respectively.

Chromosomal locations of QTLs for CTF. Arrowheads indicate the positions of LOD peaks. Bars indicate the interval with a decrease of 1.0 from the peak LOD value.

| Chromo some | Marker interval | Position of nearest marker for QTLa | LOD | PVE b (%) | AEc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | RM20923-*RM5711 | 3,174,356 | 8.1 | 19.2 | 6.2 |

| 8 | *RM22613-RM22755 | 6,731,435 | 3.2 | 7.9 | 3.7 |

| 12 | RM5282-*RM28661 | 25,612,163 | 6.7 | 14.8 | 5.0 |

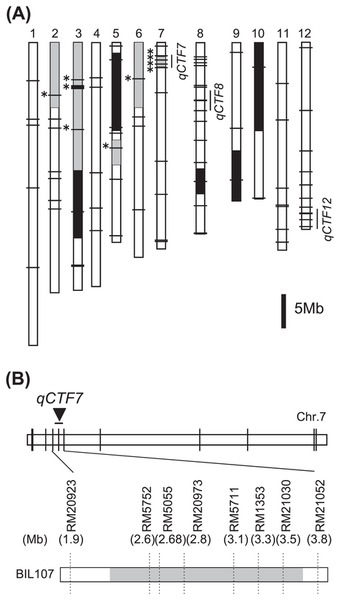

To validate the effect of qCTF7, which was the most effective QTL, QTL analysis was performed using advanced progeny selected by the genotype of the three QTLs for CTF (Fig. 6A). Using eight SSR markers, the heterozygous chromosomal region of qCTF7 in this population was determined (Fig. 6B). The frequency distribution of seed fertility after the cold temperature treatment showed a continuous variation that could be explained by the genotype of RM5711 for qCTF7, which accounted for 33.5% of the total phenotypic variation (Fig. 7 and Supplemental Table 2). Although the population had several heterozygous regions, no QTLs were detected on regions other than qCTF7. The chromosomal region of qCTF7 was in the 1.9 Mb interval between the markers RM20923 and RM21052 (Fig. 6B).

Graphical representation of the genotype of BIL107. Three genotype classes were indicated as homozygous for Suisei (white) and Eikei88223 (black) and heterozygous (shaded). (A) Whole genome genotypes by 87 SSR markers. The markers with asterisks were used for QTL analysis. (B) Graphical representation of the genotype of the target region in chromosomal 7. The number shows the position of the marker in RAP-DB build 5.0 (http://http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp).

Frequency distribution of CTF in advanced progeny. The three classified genotypes assessed by the genotype of RM5711 were as indicated; homozygous for Suisei (white) and Eikei88223 (black) and heterozygous (shaded). Horizontal and vertical lines represent ranges and mean values for Eikei88223 (E) and Suisei (S), respectively.

The development of cultivars with cold tolerance during rice growth is very important for stable rice production, especially in high latitude and high altitude areas in the world. Because cold tolerance is a complex trait, addressing the genetic base of cold tolerance will help to develop cultivars capable of adapting to cold temperature. Many QTLs for the tolerance and response of rice to cold temperature have been identified, including the seed germination stage (Fujino et al. 2004, Ji et al. 2009), seedling stage (Baurah et al. 2009, Iwata et al. 2010) and booting stage (Andaya and Mackill 2003, Dai et al. 2004, Kuroki et al. 2007, Li et al. 1997, Mori et al. 2011, Oh et al. 2004, Saito et al. 1995, Suh et al. 2010, Takeuchi et al. 2001, Xu et al. 2008, Zhou et al. 2010). Despite the significance of tolerance to cold temperature at the fertilization stage, little is known about the genetic and morphological bases of CTF. In this study, we elucidated what caused different degrees of CTF and identified the QTLs for CTF.

Cold temperature at the booting stage was shown to cause a deficiency in young microspore development (Nishiyama et al. 1976, Oliver et al. 2005). In the present study, the degradation of mature pollen grains, the inhibition of pollen germination and pollen tube elongation by cold temperature at the fertilization stage was observed (Figs. 2, 3). These phenomena may be major factors in determining the degree of CTF. The fertilization stage is known to be the most sensitive to temperature stress in several crop plants. Several reproductive tissues reacted to temperature stress (Kelly et al. 2010). Cold temperature was shown to inhibit pollen germination and shorten pollen tubes in Trifiolium ripenens and chickpea (Jakobsen and Martens 1994, Srnivasan et al. 1999). In contrast, a hot temperature (38°C) at the fertilization stage caused unsuccessful anther dehiscence, a disability in pollen germination, and pollen tube elongation on the stigma of rice (Jagadish et al. 2010). These phenomena were similar to those observed with the cold temperature treatment in this study, indicating that this stage is sensitive to unsuitable temperature rather than hot or cold temperature specifically.

In this study, we identified three QTLs controlling CTF on chromosomes 7, 8 and 12. The most effective QTL, qCTF7, was validated using advanced progeny. Although continuous variations in seed fertility could be explained by the genotype of RM5711, no plants that had homozygous allele of Eikei88223 at qCTF7 showed a vigorous CTF level equivalent to that of Eikei88223 in this population. This result suggests that an additive or epistatic interaction of qCTF7 with other QTLs could increase the degree of CTF. These QTLs and linked markers are useful for improving CTF in rice breeding program in regions with cold temperature.

Extended cold temperature during the reproductive phase often causes serious yield reductions in rice production (Suh et al. 2010, Xu et al. 2008). Not only CTF, but also CTB is necessary for high seed fertility. Many QTLs controlling CTB have been identified (Andaya and Mackill 2003, Dai et al. 2004, Kuroki et al. 2007, Li et al. 1997, Mori et al. 2011, Oh et al. 2004, Saito et al. 1995, Suh et al. 2010, Takeuchi et al. 2001, Xu et al. 2008, Zhou et al. 2010). However, these were not involved in the chromosomal regions of QTLs controlling CTF identified in this study. Although both CTB and CTF were evaluated by seed fertility, these results suggest that the genetic bases of cold tolerance may be different at each stage. The combination of QTLs controlling CTB with those controlling CTF may improve cold tolerance during the reproductive phase in rice.

Due to intensive breeding efforts, the genetic diversity of modern rice cultivars has been reduced (Cuevas-Perez et al. 1992, Dilday 1990). The intense focus on eating quality may narrow genetic diversity among local populations in Japan (Nagasaki et al. 2010, Yamamoto et al. 2010, Yonemaru et al. 2012). Polymorphisms in the tested SSR markers between Eikei88223 and Suisei were very low, indicating that these cultivars were in a genetically close relationship. Besides having genetically close relationships, a relatively wide phenotypic diversity for CTF may be involved in the gene pool of the rice population in Hokkaido. Three cultivars from different pedigrees (Supplemental Fig. 3), Eikei88223, Hokkai302 and Hoshimaru exhibited vigorous CTF (Table 1). These cultivars could be sources of cold tolerance genes at the fertilization stage. Understanding the genetic bases of CTF involved in this gene pool will be useful for the introduction of vigorous CTF into commercial rice cultivars in rice breeding program.