2013 年 63 巻 2 号 p. 205-210

2013 年 63 巻 2 号 p. 205-210

We studied the effects of drying of immature seeds of vegetable soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) on the accumulation of gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA) in the seeds. GABA accumulated after heat-drying, with the maximum at 40°C. The GABA content (447.5 mg/100 g DW) increased to more than 5 times the value in untreated seeds (79.6 mg/100 g DW). In contrast, the glutamate content decreased rapidly to 1/3 the level in the untreated seeds. The GABA content increased early in the heat-drying treatment: after 30 min, it had increased to 1.5 times the value in the untreated seeds. GABA did not accumulate in the vacuum-drying treatment. Among genes related to the GABA shunt, the gene for glutamate decarboxylase (EC 4.1.1.15), which catalyzes the decarboxylation of glutamate to produce GABA, showed relatively high expression, decreasing to only 70% of the value in untreated seeds even after 4 h of treatment. In contrast, expression of the genes for two catabolic mitochondrial enzymes, GABA transaminase (GABA-T; EC 2.6.1.19) and succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH; EC 1.2.1.16), decreased rapidly during heat-drying. These results suggest that the accumulated GABA was not metabolized rapidly by GABA-T and SSADH and therefore remained at high levels.

The immature seeds of vegetable soybean (edamame) are edible when cooked. Many vegetable soybean cultivars are grown in Japan. The immature seeds of some contain high amounts of free cellular components such as sugars and amino acids that contribute to their palatability (Abe et al. 2004, Masuda et al. 1988, Yanagisawa et al. 1997). Among the free amino acids, asparagine, alanine and glutamate have been reported to be major components of immature seeds (Yanagisawa et al. 1997). Some cultivars also contain relatively high contents of gamma-(γ) aminobutyrate (GABA) (Abe and Takeya 2005). GABA is a four-carbon, non-protein amino acid that is synthesized by decarboxylation of glutamate by glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), which is activated by Ca2+-calmodulin (Shelp et al. 1999, Snedden et al. 1995). GABA is transaminated in the mitochondria by GABA transaminase (GABA-T) to form succinic semialdehyde, which is then oxidized by succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) to succinate (Allan et al. 2009, Shelp et al. 1999, Tuin and Shelp 1996). These metabolic pathways are referred to as the “GABA shunt” and they have been studied in the context of enzyme activities and responses to environmental signals such as drought stress, hypoxia, and acidosis mechanical stress (Allan et al. 2008, Guo et al. 2012).

GABA may accumulate in soybean seeds during germination after soaking of seeds in water for several hours (Guo et al. 2011). Changes in GAD activities also occur during germination (Matsuyama et al. 2009, Oh and Choi 2001). Until recently, there have been few reports of GABA metabolism and genetics in immature vegetable soybean. Abe and Takeya (2005) reported that relatively high levels of GAD mRNA occurred in developing vegetable soybean at 15 to 35 days after flowering. GABA is a “functional” amino acid and has beneficial effects such as decreasing blood pressure (Stanton 1963).

Here, we found that heat-drying enhanced GABA accumulation in immature vegetable soybean seeds. We elucidated the relationships between GABA accumulation and the expression of related genes (Gm GAD1, Gm GABA-T1, Gm SSADH1) during heating and drying of the seeds.

In 2009, we grew four vegetable soybean cultivars (Shirayama-dadacha, Kanro, Sapporo-midori and Hiden) in a field at Yamagata University (Yamagata, Japan). During plowing, inorganic fertilizer was applied at a rate of 55.5 kg N, 194.5 kg P2O5 and 104 kg K2O per Ha. Immature pods were harvested when they reached the edible stage, which occurred 35 days after flowering for Shirayama-dadacha, Kanro and Sapporo-midori and 55 days after flowering for Hiden. The immature pods were immersed in liquid nitrogen and stored in a freezer at −80°C until analysis.

Drying treatmentsIn preliminary experiments, we found that GABA accumulated after heat-drying of the immature seeds. So after taking out immature seeds from their frozen pods, we weighed them and then dried them at 20, 40, 60, or 80°C for 72 h. For the analysis of the changes in glutamate and GABA levels, dried them at 40°C for up to 4 h. We also evaluated the effects of vacuum-drying: we weighed the frozen seeds, placed them in 20-mL test tubes, immersed them in liquid nitrogen and stored them in a vacuum dryer (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) at about 20°C for up to 4 h. In each treatment, we calculated the amount of evaporated H2O and the water content of the samples after drying.

Analysis of free amino acidsWe determined the concentrations of free amino acids in the dried seeds using the phenylthiocarbamyl (PTC) amino acid conversion method (Cohen and Strydom 1985). After removal of the hypocotyl of the immature seeds, the cotyledons were weighed 100 mg. The measured samples were homogenized in 1.5 mL of 80% ethanol for 2 min and then collected into Eppendorf tubes. The sample tubes were treated in boiling water with refluencing for 10 min. Then they were centrifuged at 12000 × g for 20 min and the supernatants were collected. The supernatants were dried by vacuum centrifuging at 6000 × g and 40°C. The pellets were suspended in a 1: 1 v/v solution of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile and then filtered through a SEP-PAC C18 column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The filtered amino acids were dried by vacuum centrifuging at 6000 × g and 40°C. The pellets were treated with 20 μL of washing solution (2: 1: 1 v/v/v ethanol: H2O: TEA) and then dried. The washed pellets were treated with phenyl isothiocyanate solution (7: 1: 1: 1 v/v/v/v ethanol: H2O: TEA PITC) for 20 min at room temperature to convert the amino acids into PTC amino acids. The PTC amino acids were then suspended in 100 μL of PTC amino acid diluting solution (95: 5 v/v 0.05 M Na2HPO4: CH3CN). The PTC amino acid solutions were then analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (Waters 600E system) on a Pico-Tag column (Waters). The PTC amino acids were detected using a UV detector (Waters 486 tunable absorbance detector) at 254 nm.

Extraction of total RNATotal RNAs were extracted by using the sodium dodecyl sulfate–phenol method (Kirby 1968). After removal of the hypocotyl, cotyledons were immersed in liquid nitrogen and powdered with a mortar and pestle. The cotyledon powder was ground in a solution of 0.5 mL 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.5) plus 0.5 mL 90% phenol that was then neutralized by the addition of 1/100 volume of 5 N NaOH and centrifuged at 12000 × g for 20 min. The upper water phase was transferred into new tubes and the RNA was purified twice with chloroform by centrifuging at 12000 × g for 5 min. The purified water-phase RNA solution was adjusted to pH 5.0 by the addition of small amount of acetic acid and then precipitated with addition of 0.05 volume of 4 M NaCl and 0.6 volume of isopropanol. The RNA pellets were collected by centrifugation at 12000 × g for 10 min, rinsed once with 70% ethanol and resuspended in RNase-free Tris·EDTA (etylenediaminetetraacetic acid) buffer (10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). The total RNA was adjusted to a uniform concentration by measurement of the absorption at 260 nm with a DU-64 spectrophotometer (Beckman, La Brea, CA, USA) and the addition of Tris·EDTA buffer to produce the desired final concentration.

Gene expression analysisWe used 500 ng of total RNA to perform the reverse transcription reaction using the oligo-dT adapter primer and AMV reverse-transcriptase XL (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). We performed the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using version 3.0 of the Takara RNA PCR Kit (Takara, Kusasu, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR conditions were 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s and 72°C for 40 s, with no initial denaturation or final extension. Table 1 provides the specific primer sets used for each gene. The primers were designed using the Primer 3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky 2000) to produce DNA fragments of 150 to 250 bp. The PCR products were electrophoresed in 3% agarose gel. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and exposed to UV light to detect the amplified DNA. The intensity of the bands was analyzed using version 3.0 of the CS Analyzer software (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan).

| Genes | Accession numbera | Primer sequences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| GmGAD1 | AB240965 | 5′-attgccccatttctttaccc-3′ | 5′-gggttgatcagcaccaagat-3′ |

| GmGABA-T1 | AK244308 | 5′-cctcctgaatggggagtagg-3′ | 5′-gcctaagctacttgcgctga-3′ |

| GmSSADH1 | BW651520 | 5′-cttagctgcagcggaactc-3′ | 5′-gctgaaccagccatcaattt-3′ |

| GmActin 1 | J01298 | 5′-tccgagagaaagttcggtgt-3′ | 5′-caattgatggtccagactcg-3′ |

Fig. 1 shows the appearance of the untreated and heat-treated immature vegetable soybean seeds. We used the water contents of seeds from the four cultivars to calculate the content of amino acids. The water contents in the fresh immature seeds differed among cultivars, ranging from 61.5% to 76.8% (Table 2). After 4 h of the two drying treatments, water was evaporated until the seeds were completely dehydrated (Table 3).

Appearance of the immature vegetable soybean seeds. A: untreated seeds, B: seeds after heat-drying at 40°C for 24 h.

| Cultivar | Initial seed weight (g) | Evaporated water (g) | Water content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shirayama-dadacha | 0.662 ± 0.022 | 0.492 ± 0.013 | 74.3 ± 1.86 |

| Kanro | 0.683 ± 0.020 | 0.495 ± 0.010 | 72.5 ± 1.88 |

| Sapporo-midori | 0.621 ± 0.026 | 0.477 ± 0.020 | 76.8 ± 1.65 |

| Hiden | 0.942 ± 0.013 | 0.579 ± 0.077 | 61.5 ± 0.12 |

Values are means ± SD (n = 10).

| Duration of treatment (h) | Initial seed weight (g) | Seed weight after treatment (g) | Evaporated water (g) | Evaporated water (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat drying | ||||

| 0.5 | 0.650 ± 0.076 | 0.546 ± 0.070 | 0.104 ± 0.006 | 16.0 ± 1.56 |

| 1 | 0.531 ± 0.072 | 0.383 ± 0.067 | 0.148 ± 0.019 | 27.9 ± 1.44 |

| 2 | 0.609 ± 0.048 | 0.342 ± 0.033 | 0.267 ± 0.016 | 43.8 ± 1.90 |

| 3 | 0.560 ± 0.038 | 0.167 ± 0.043 | 0.393 ± 0.021 | 70.2 ± 1.95 |

| 4 | 0.606 ± 0.032 | 0.158 ± 0.029 | 0.448 ± 0.055 | 73.9 ± 4.52 |

| Vacuum drying | ||||

| 0.5 | 0.598 ± 0.089 | 0.381 ± 0.039 | 0.218 ± 0.024 | 36.5 ± 2.83 |

| 1 | 0.567 ± 0.031 | 0.267 ± 0.047 | 0.300 ± 0.094 | 52.9 ± 6.36 |

| 2 | 0.623 ± 0.005 | 0.261 ± 0.021 | 0.362 ± 0.026 | 58.1 ± 4.10 |

| 3 | 0.569 ± 0.030 | 0.186 ± 0.013 | 0.383 ± 0.041 | 67.3 ± 3.39 |

| 4 | 0.567 ± 0.008 | 0.142 ± 0.065 | 0.425 ± 0.059 | 75.0 ± 3.96 |

Values are means ± SD (n = 10).

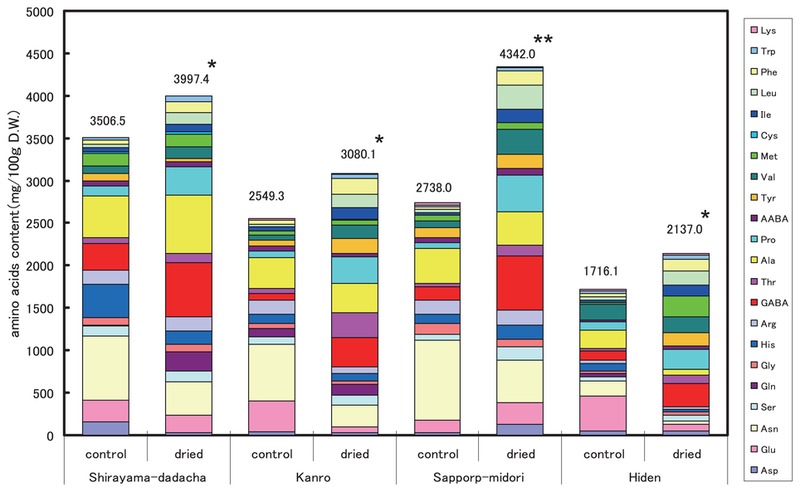

The free amino acid contents of the untreated and treated seeds of the four cultivars are shown in Fig. 2. In the untreated immature seeds, the total free amino acid contents ranged from 1716 to 3507 mg/100 g DW. After heat-drying for 3 days, the concentrations increased to between 2137 and 4342 mg/100 g DW. The ratio of the content in the dried seeds to that in the untreated seeds was 1.14 for Shirayama-dadacha, 1.21 for Kanro, 1.59 for Sapporo-midori and 1.25 for Hiden. Among the amino acids, GABA, alanine and proline increased drastically; GABA increased most, whereas glutamate and glutamine decreased.

Comparison of amino acid contents in the heat-treated and untreated immature vegetable soybean seeds. The heat treatment was conducted at 40°C for 3 days. *: significantly different at 5%, **: significantly different at 1%

Of the four drying temperatures, 40°C was most effective for promoting GABA accumulation in Shirayama-dadacha (Fig. 3). The GABA content increased to 447.5 mg/100 g DW at 40°C for 3 days, versus 79.6 mg/100 g DW in the untreated immature seeds. This represents an increase to more than 5 times the control value. At temperatures hotter than 40°C, GABA also increased, but to a lower level than at 40°C. Thus, heat-drying at 40°C is the most suitable condition to increase GABA accumulation in the immature seeds.

Changes in GABA accumulation in immature vegetable soybean seeds of Shirayama-dadacha after treatment at various temperatures.

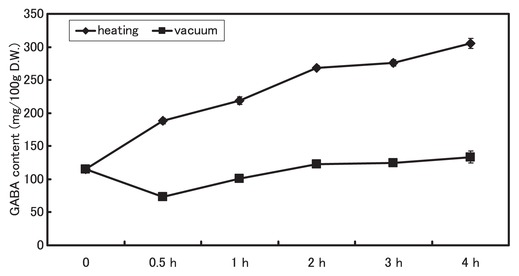

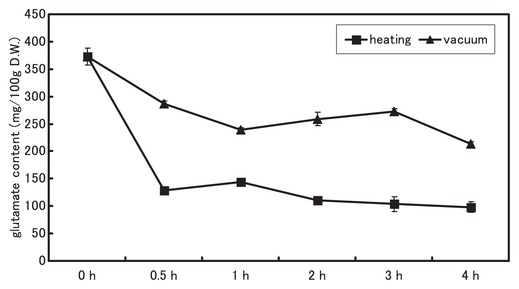

We clarified the GABA accumulation at various times during the two drying treatments in a cultivar, Shirayama-dadacha. GABA accumulated rapidly during the early heat-drying period: after 30 min, it had increased to about 1.5 times the initial value and then increased further as time passed (Fig. 4). In contrast, it remained mostly stable in the vacuum-drying treatment (Fig. 4). On the other hand, glutamate, which is the substrate for GABA synthesis, decreased rapidly to 1/3 of the initial level after 30 min of the heat-drying treatment, but decreased only slowly in the vacuum-drying treatment (Fig. 5).

Changes in GABA levels in immature vegetable soybean seeds of Shirayama-dadacha after the heat-drying and vacuum-drying treatments.

Changes in glutamate levels in immature vegetable soybean seeds of Shirayama-dadacha after the heat-drying and vacuum-drying treatments.

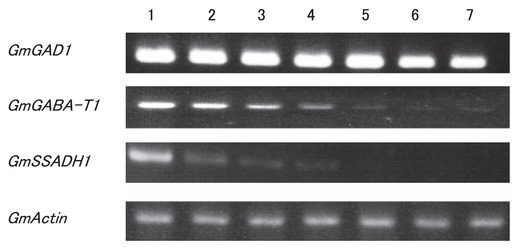

We assessed the changes in gene expression by means of RT-PCR using total RNAs of Shirayama-dadacha. In preliminary experiments, we determined the optimal conditions for the amount of total RNA (500 ng) required to generate cDNA and found that the optimum number of PCR cycles was 30, for the three genes involved in the GABA shunt. We assessed the integrity and amount of RNA by the expression levels of actin (GmActin1). We conducted each RT-PCR more than two times and because we obtained similar results, we have only presented a single representative example. The levels of GmGAD1 mRNA were relatively high even after heat-drying for 4 h, although they gradually decreased to 70% of the control value after 4 h (Fig. 6). In contrast, levels of GmGABA-T1 and GmSSADH1 mRNA decreased rapidly during the heat-drying treatment and both mRNAs were not detected after 2 h for GmSSADH1, and 4 h for GmGABA-T1 (Fig. 6).

Changes in the levels of GAD, GABA-T and SSADH mRNAs after heat-drying of the immature seeds of Shirayama-dadacha. Lanes: 1, control (untreated seeds); 2, heat-drying for 10 min; 3, heat-drying for 30 min; 4, heat-drying for 1 h; 5, heat-drying for 2 h; 6, heat-drying for 3 h; 7, heat-drying for 4 h.

Though the immature vegetable soybean seeds are edible after boiling, the boiling degrades the free amino acids (Abe et al. 2004, Miyake et al. 2007). On the other hand, during germination, the contents of many amino acids increase, especially those of alanine, proline and GABA (Mizuno and Yamada 2007). GABA is a functional amino acid that plays an important role in human health, so some scientists have focused on GABA accumulation and related enzyme activity in soybean seeds (Guo et al. 2011, Matsuyama et al. 2009).

In our study, GABA accumulated to between 4 and 5 times the control value in immature vegetable soybean seeds after heat-drying, which represents an abiotic stress on the cotyledon tissues. The GABA accumulated early in the drying treatments and the most effective temperature for stimulating the accumulation was 40°C. In contrast, vacuum-drying did not cause GABA accumulation. These results suggest that to enhance GABA accumulation, heat-drying under aerobic conditions is important. However, heating at 60°C and 80°C also brought GABA accumulation, though the levels were lower than that at 40°C. It could be assumed that the enzyme, soybean GAD is a little thermo stable and might work in the beginning of the heat-drying treatment even at high temperatures, 60 and 80°C. And because we did not test heating under anaerobic condition and humid condition, it is unclear which is more effective, heating or drying, for accumulation of GABA. This should be tested in future research. Guo et al. (2011) reported that GABA accumulated during the germination of soybean in an aerobic treatment at 30°C in a dark incubator. In contrast, levels of glutamate, the substrate for GABA production, decreased rapidly (i.e., levels were inversely proportional to GABA levels) after the onset of heat-drying. These result suggest that glutamate was decarboxylated to produce GABA under these conditions and that the glutamate was not supplied by the GABA shunt. Clark et al. (2009) have reported that knockout lines of soybean that lack the gene that encodes GABA-T, which catalyzes transamination of GABA and leads to its conversion into succinate semialdehyde, produced more GABA than the wild-type plants.

We investigated the expression of three genes related to the GABA shunt to provide insights into why GABA accumulated during heat-drying. Although GABA accumulated rapidly during heat-drying, the level of mRNA for the gene that encodes GAD did not increase and it was maintained at about 70% of the control level even after 4 h of heat-drying. The key factors in GABA accumulation therefore appear to be expression of the genes that encode GABA-T and SSADH, which transform GABA into other compounds. Our results show that levels of mRNAs of the genes that encode GABA-T and SSADH decreased rapidly, whereas levels of mRNA for the gene that encodes GAD remained high, even after heat-drying. These results suggest that the GABA was not metabolized rapidly by GABA-T and SSADH and therefore remained at high levels.

The authors thank Professor, B. Shelp, The University of Guelph, for his valuable suggestion for this study.