2013 Volume 63 Issue 3 Pages 333-338

2013 Volume 63 Issue 3 Pages 333-338

Chili anthracnose, caused by Colletotrichum spp., is one of the major diseases to chili production in the tropics and subtropics worldwide. Breeding for durable anthracnose resistance requires a good understanding of the resistance mechanisms to different pathotypes and inoculation methods. This study aimed to investigate the inheritances of differential resistances as responding to two different Colletotrichum pathotypes, PCa2 and PCa3 and as by two different inoculation methods, microinjection (MI) and high pressure spray (HP). Detached ripe fruit of Capsicum baccatum ‘PBC80’ derived F2 and BC1s populations was assessed for anthracnose resistance. Two dominant genes were identified responsible for the differential resistance to anthracnose. One was responsible for the resistance to PCa2 and PCa3 by MI and the other was responsible for the resistance to PCa3 by HP. The two genes were linked with 16.7 cM distance.

Chili or Capsicum spp. is one of the world top ranked vegetables, as well as an important spice and medicinal plant (Allison 2002). The world production was approximately 26.8 and 2.8 Mt for fresh and dried fruit (FAOSTAT 2010). Chili anthracnose is not only a serious problem in Asia (Park 2007, Poonpolgul and Kumphai 2007, Ramachandran et al. 2007), but also a major constraint to the chili production in the tropics and subtropics worldwide such as USA (Harp et al. 2008, Lewis Ivery et al. 2004) and Brazil (Tozze Jr. and Massola Jr. 2009).

The first report of differential resistance to chili anthracnose was found by genetic studies in where resistances in mature green and ripe fruit stages were conferred by different genes (Mahasuk et al. 2009a, 2009b). Two recessive genes were identified in an interspecific cross of C. annuum cv. ‘Bangchang’ × C. chinense ‘PBC932’, each of which conferred the resistance in mature green and ripe fruit stages respectively. While in an intraspecific cross of C. baccatum, the PBC80-derived resistance was controlled by a dominant gene in the ripe fruit and by a recessive gene in the mature green fruit.

Three Colletotrichum species including C. truncatum (syn. capsici), C. gloeosporioides and C. acutatum have been reported as the major causal agents of chili anthracnose (Mongkolporn et al. 2010, Than et al. 2008). Pathogenicity study of the three Colletotrichum speices on a set of ten differential chili genotypes grouped each Colletotrichum species into pathotypes (Mongkolporn et al. 2010, Montri et al. 2009). The pathotypes were classified based on qualitative differential reactions on host ie. infected vs not infected (Taylor and Ford 2007). Three pathotypes of C. acutatum were identified on mature green fruit stage (Mongkolporn et al. 2010). Pathotype 1 (PCa1) of C. acutatum was able to infect all chili genotypes of C. annuum, C. frutescens, C. chinense and C. baccatum. PCa2 was not able to infect C. baccatum ‘PBC80’ and PCa3 was not able to infect C. baccatum ‘PBC80’ and ‘PBC81’.

Among the three species of Colletotrichum, C. acutatum appears to be the most aggressive pathogen, which can infect all tested four Capsicum species ie. C. annuum, C. frutescens, C. chinense and C. baccatum (Mongkolporn et al. 2010, Than et al. 2008). To date, Capsicum baccatum ‘PBC80’ has exhibited the widest resistance to all three Colletotrichum species, except for the PCa1, however the infection only occurred on the mature green fruit (Mongkolporn et al. 2010, Temiyakul et al. 2012).

Resistance to anthracnose in C. baccatum ‘PBC80’ was firstly identified by the AVRDC (the World Vegetable Center, Taiwan) after fruit were inoculated using a microinjector (AVRDC 1999). Since the microinjection (MI) inoculation method has been widely adopted and adapted to assess anthracnose resistance on detached chili fruit in breeding programs (Kim et al. 2008a, 2008b, Lee et al. 2011, Mahasuk et al. 2009a, 2009b, Pakdeevaraporn et al. 2005) and pathogenicity studies (Mongkolporn et al. 2010, Montri et al. 2009, Temiyakul et al. 2010). The MI delivers uniform quantity of inoculum and can be used on detached fruit, which enables an efficient mass inoculation in a short time. However the method needs to make a tiny wound (~1 mm diameter and depth) on chili pericarp. Although the MI has been claimed to be a too harsh inoculation, the selection for anthracnose resistance was successful (Mahasuk et al. 2009a, 2009b, Mongkolporn and Taylor 2011, Pakdeevaraporn et al. 2005). Mahasuk et al. (2009b) demonstrated that the immune resistance on the chili fruit of C. baccatum ‘PBC80’, which was the chili resistant line used in this current study, inoculated by MI was a result of hypersensitive reaction (HR).

MI has been utilized as a mean to deliver fungal spores into chili fruit in our genetic and pathogenicity studies on chili anthracnose resistance (Kanchana-udomkan et al. 2004, Mahasuk et al. 2009a, 2009b, Mongkolporn et al. 2010, Montri et al. 2009, Pakdeevaraporn et al. 2005, Temiyakul et al. 2010, 2012). While the method has been criticized as a harsh and not natural inoculation, immune resistance with hypersensitive reaction accomplishedly shows in the resistant accessions of C. chinense ‘PBC932’ (Mahasuk et al. 2009a) and C. baccatum ‘PBC80’ (Kim et al. 2007, Mahasuk et al. 2009b). These immune resistances are highly heritable. Recently the AVRDC (The World Vegetable Center, Taiwan) has developed a high pressure spray (HP) in 2008 (unpublished data), which utilized an airbrush to deliver fungal spores onto chili fruit. HP is considered a lesser harsh method than MI due to its non wounding nature and could be replaced the MI, if HP is proven to be as reliable as MI.

This study aimed to investigate the resistances derived from ‘PBC80’ in response to different Colletotrichum pathotypes (PCa2 vs PCa3) and as by two different inoculation methods (MI vs HP). The HP developed by AVRDC was modified and optimized in this study (data not shown). The outcomes of the study would bring a better understanding of the host-pathogen interaction of chili anthracnose, which will be greatly beneficial to the chili breeding programs.

An intraspecific cross between two C. baccatum genotypes, ‘PBC80’ (P1; resistant variety) and ‘CA1316’ (P2; susceptible variety) and a reciprocal F1 cross were produced. Chili populations including ten plants each of P1, P2, F1 and reciprocal F1; 160 F2s; 65 BC1P1s and 90 BC1P2s were grown at an experimental field of the Department of Horticulture, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand from May to October 2011.

Two Colletotrichum acutatum isolates including Ca313 and CaMJ5 which have been classified as PCa2 and PCa3 respectively by Mongkolporn et al. (2010) were cultured on PDA (potato dextrose agar; DifcoTM, Becton, Dickinson and Company, MD, USA) for 7 days at 25°C under 12 h fluorescent light. Spore suspension was prepared to the concentration of 106 spores/ml following Montri et al. (2009).

Inoculation methods Microinjection (MI)A microinjector comprised a Micro Syringe model 1705 TLL and a dispenser PB600-1 (Hamilton, Switzerland) attached with a needle (1 mm in diameter and 1 mm in length), delivered approximately 1,000 spores into a chili fruit through pericarp (Kanchana-udomkan et al. 2004).

High pressure spray (HP)A HP sprayer, comprising an airbrush model TG-3F (Paasche®, USA.) and an air compressor model ACA 201 (K. Setthakit, Thailand), delivered approximately 6,000 spores onto the surface of a chili fruit. The HP sprayer’s pressure was adjusted to 2 kg/cm2 (30 psi). The sprayer was positioned at 5 cm above the fruit during spraying.

Ten chili fruit at ripe stage (~40–45 days after flowering; DAF) were collected from each plant of all chili populations. Five fruit were each inoculated with two pathotypes using the MI method by injecting the prepared inoculums of Ca313 and CaMJ5 at the center of each fruit side respectively (Temiyakul et al. 2010). Another set of five chili fruit were inoculated with CaMJ5 by the HP method.

Anthracnose resistance assessmentThe inoculated fruit was incubated in a plastic box half filled with water to maintain high humidity, at room temperature (~25–30°C) under 12 h alternate light/dark cycles for 3 days. Fruit of ‘Bangchang’ (C. annuum) was inoculated with sterilized water using MI and HP serving as negative control; and was inoculated with Ca313 and CaMJ5 serving as positive control. Anthracnose symptoms were visually assessed at 9 days after inoculation using the disease scales developed by Montri et al. (2009). Scores 1–9 were given based on % lesion size in proportion to the whole fruit size (Table 1).

| Scores | Symptom descriptions | |

|---|---|---|

| Microinjection | High pressure spray | |

| 0 | No infection or localized cell death surrounding injection wound on the fruit | No infection or localized cell death spreading covering the sprayed area on the fruit surface |

| 1 | 1–2% of the fruit area shows necrotic lesion or a larger water soaked lesion surrounding the infection site | |

| 3 | >2–5% of the fruit area shows necrotic lesion, acervuli may be present/or water soaked lesion up to 5% of the fruit surface | |

| 5 | >5–15% of the area shows necrotic lesion, acervuli present/or water soaked lesion up to 25% of the fruit surface | |

| 7 | >15–25% of the fruit area shows necrotic lesion with acervuli | |

| 9 | >25% of the fruit area shows necrosis, lesion often encircling the fruit, abundant acervuli | |

Distribution of disease scores derived from each Colletotrichum isolate and each inoculation method was analyzed. Resistant (R) and susceptible (S) phenotypes were classified based on the parental performance. Frequency of each phenotype was determined and the segregation ratio of R to S was analyzed to fit a Mendelian segregation ratio using a χ2 test.

Linkage between genes that controlled the resistance was analyzed by considering the segregation of possible phenotypic combinations for each pair of genes. Segregation of the phenotypic combination for each pair of genes was analyzed to fit a ratio based on the Mendelian law of independent assortment using a χ2 test. If the segregation did not fit a Mendelian ratio, then recombinant phenotypes, which resulted from crossing over of the two genes were calculated.

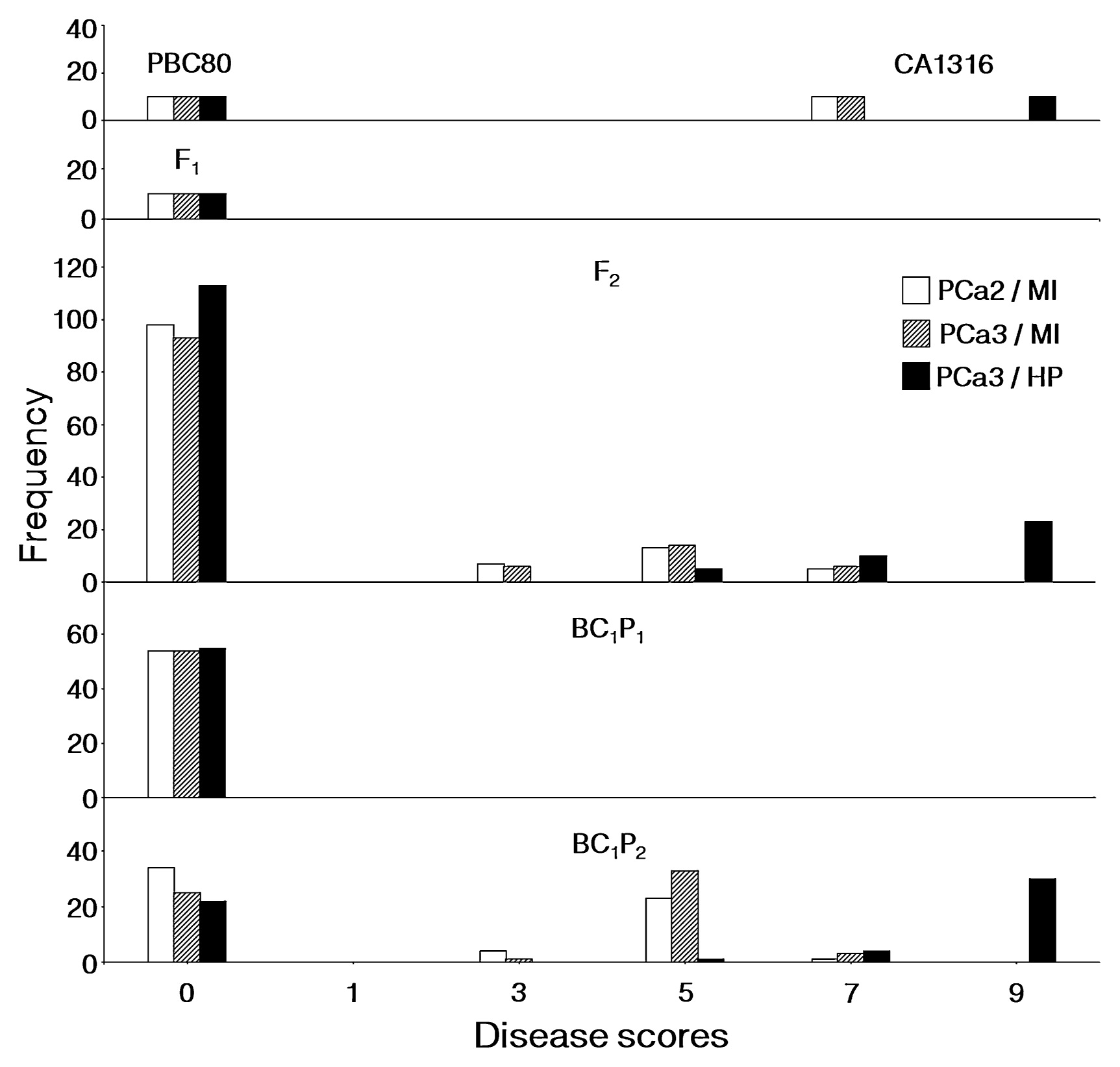

Considering the disease score distribution caused by two pathotypes and two inoculation methods in all chili populations (Fig. 1), the F2s were clearly separated into two groups. One of which resembled the resistant parent ‘PBC80’ with the disease score of ‘0’, while the other ranged from either scores 3 to 7 (by MI) or 5 to 9 (by HP). Therefore two phenotypes were classified including R (resistance, score ‘0’) and S (susceptibility, scores greater than ‘3’).

Distribution of disease severity scores on ripe fruit of Capsicum baccatum ‘PBC80’ derived populations, at 9 days after inoculation with two Colletotrichum acutatum pathotypes (PCa2 and PCa3) by microinjection (MI) and high pressure spray (HP).

Anthracnose disease scores caused by both Ca313 and CaMJ5 as evaluated on ripe fruit at 9 DAI in the parents ‘PBC80’ and ‘CA1316’ were 0 and 7 respectively. All F1 plants, as well as the reciprocal F1 (data not shown), resembled the resistant parent ‘PBC80’ (Fig. 1). The disease score distribution, caused by both pathotypes, in the F2 was similarly skewed toward the ‘PBC80’, suggesting that the resistance to each pathotype was a dominant trait. The segregation of the disease scores caused by each pathotype in the F2 suggested a single gene model with two phenotypic classes. The disease score distribution in the F2 clearly separated into two groups (score ‘0’ vs scores ‘3’ and greater, which therefore were used to classify the phenotypes R and S respectively. The χ2 test fit a 3 : 1 Mendelian segregation ratio for R and S suggesting a single dominant gene responsible for the resistance caused by either Colletotrichum pathotype. The segregation in both BC1 populations also confirmed the single gene model (Table 2).

| Chili population | Ca313/MI | CaMJ5/MI | CaMJ5/HP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | S | χ2 | P | R | S | χ2 | P | R | S | χ2 | P | |

| P1 | 10 | 0 | – | – | 10 | 0 | – | – | 10 | 0 | – | – |

| P2 | 0 | 10 | – | – | 0 | 10 | – | – | 0 | 10 | – | – |

| F1 | 10 | 0 | – | – | 10 | 0 | – | – | 10 | 0 | – | – |

| F2 | 98 | 25 | 1.43 | 0.23 | 93 | 26 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 113 | 38 | 0.002 | 0.96 |

| BC1P1 | 54 | 0 | na | na | 54 | 0 | na | na | 55 | 0 | na | na |

| BC1P2 | 34 | 28 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 25 | 37 | 2.32 | 0.13 | 22 | 35 | 2.97 | 0.09 |

R = resistance; S = susceptibility; na = not applicable; P = probability.

Genetic analysis of the resistance to CaMJ5 as inoculated by HP method also exhibited a single gene model (Table 2) with R as a dominant trait. Two phenotypic classes including R and S were identified. The phenotypic segregation in the BC1 populations confirmed the single gene model as found in the F2.

Independence analyses among the identified resistance genesGene independence analyses were performed for all the resistance genes identified in this study. For the resistance to Ca313 and CaMJ5 using MI method, not all plants set fruit for inoculation, therefore 100 F2 plants were available for linkage analysis. Considering the combination of the two dominant genes, four phenotypes were investigated including (i) R to both Ca313 and CaMJ5, (ii) R to Ca313 and S to CaMJ5, (iii) S to Ca313 and R to and CaMJ5 (iv) S to both Ca313 and CaMJ5. On the basis that if the two genes were independent, the segregation of the four phenotypes would fit 9 : 3 : 3 : 1. There were no plants exhibiting the (ii) and (iii) combined phenotypes, which strongly suggested that the resistance to Ca313 and CaMJ5 was controlled by the same gene.

For the independence analysis of the resistance genes by MI and by HP, 96 F2 plants were available. Goodness-of-fit test for a 9 : 3 : 3 : 1 combined phenotype segregation was performed and suggested that the two R genes were not independent, but linked with genetic distance of 16.67 cM (Table 3).

| Phenotypes | E | O | χ2 | P | RF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R by MI and HP | 54 | 65 | 28.63 | <0.0001 | 16.67% |

| R by MI, S by HP | 18 | 12 | |||

| S by MI, R by HP | 18 | 4 | |||

| S by MI and HP | 6 | 15 |

E = expected frequency; O = observed frequency; P = probability; RF = recombination frequency.

Consequently, this study identified two dominant genes, one of which conferred the resistance to Ca313 and CaMJ5 by MI, and the other conferred the resistance to CaMJ5 by HP.

The resistances to different Colletotrichum acutatum pathotypes derived from C. baccatum ‘PBC80’ appeared to be controlled by the same gene. Plant disease resistance is a consequence of the host-pathogen interaction explained by gene-for-gene concept (Flor 1955), whereby the resistance is activated by a host specific recognition on the invading pathogen. This could be explained that the two pathotypes may have carried the same avirulence (Avr) gene serving as an elicitor and triggered the same R gene from the host to respond.

Differential resistances to anthracnose as responded by two inoculation methodsDifferent inoculation methods (MI vs HP) resulted in a single dominant gene model for the anthracnose resistance derived from ‘PBC80’, with two different genes being expressed for each method. These two newly identified genes were not identical based on the gene independence analysis in this study, however, they could be allelic which requires further study to prove this.

A genetic study on chili anthracnose resistance has been done previously in ‘PBC80’-derived population but with different S parent (Mahasuk et al. 2009b), using the same pathogen (CaMJ5) and MI method. The study identified a dominant gene controlling the resistance in ripe fruit. The gene was named Co5 (Table 4), which could be identical or allelic to the genes currently identified.

| Gene name | Plant growth stages | Chili population | Colletotrichum isolatea/pathotypeb/inoculation methodc | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| co1 | Mature green fruit | C. chinense ‘PBC932’* × C. annuum cv. ‘Bangchang’ | Ct158ci/PCc1/MI | Pakdeevaraporn et al. 2005, Mahasuk et al. 2009a |

| co2 | Ripe fruit | |||

| co3 | Seedling | |||

| co4 | Mature green fruit | C. baccatum ‘PBC80’* × ‘PBC1422’ | CaMJ5/PCa3/MI | Mahasuk et al. 2009b |

| Co5 | Ripe fruit | |||

| na | Ripe fruit | C. baccatum ‘PBC80’* × ‘CA1316’ | Ca313/PCa2/MI and CaMJ5/PCa3/MI CaMJ5/PCa3/HP |

This study |

| na |

The host resistance reactions derived from both MI and HP similarly were hypersensitivity (Fig. 2). The hypersensitive reaction (HR) by MI found on ‘PBC80’ fruit has been reported by Mahasuk et al. (2009b), which appeared as small brown spots of dead cells surrounding the injection wound on the fruit. With HP, the HR appeared as small black or brown spots spreading covering the sprayed area on the fruit surface. These findings indicated that MI and HP activated the same defense mechanism in chili fruit. The cell anatomy study of HR on chili fruit with MI by Kim et al. (2004) showed that MI delivered the fungal spores into the cuticle of ‘PBC80’ resistant fruit. Whilst HP used pressure to just bruise the fruit surface (less severe wound). Therefore, this study suggested that chili fruit was triggered the same defense HR mechanism, in spite of with the different inoculation methods.

Hypersensitive host reaction on ripe fruit of Capsicum baccatum ‘PBC80’ by microinjection (top) and high pressure spray (bottom).

However, the genetic analysis identified two different resistance genes (or yet to be proven as allelic) with different inoculation methods, MI and HP. Although both genes were involved in the same HR defense responses on the host, the speeds of their HR responses were different. The ‘PBC80’ fruit inoculated by MI exhibited HR at 3 DAI, while the fruit inoculated by HP exhibited the HR at 5 DAI. The different speed of the HR to appear on fruit was probably due to the different level of access of the germinated fungal spores to effectively infect host cells by MI and HP. The MI was a wounding method, hence was able to deliver the fungal spores faster than the non wounding HP. Plant defense mechanisms (including HR) have been well documented to be a consequence of a suite of defense genes (Iakimova et al. 2005). Both methods enabled infection at different speed (timing) therefore would trigger different defense genes in the mechanism. In this case one of the genes (as responded to MI) acted earlier than the other (as responded to HP) according to the different timing to detect HR on the fruit.

HP has proven to be as reliable as the MI method, based on the fact that HP can select the resistance trait as efficient as the MI, regardless of the resistance genes. The HP has been optimized with the chili fruit type in this study for the inoculum volume and the spraying distance between the airbrush and the fruit surface, to maintain the same reliability and consistency as the MI. However HP has some limitation in that HP cannot perform a double inoculation, while the MI can.

We thank the National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, National Science and Technology Development Agency (Thailand) and the East-West Seed Company Limited for financial support to this project; a PhD scholarship by the Royal Golden Jubilee/Thailand Research Fund and Kasetsart University and by the Center of Excellence on Agricultural Biotechnology, Science and Technology Postgraduate Education and Research Development Office, Office of Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education. (AG-BIO/PERDO-CHE); a Master scholarship by the Center for Advanced Studies for Agriculture and Food, Institute for Advanced Studies, Kasetsart University Under the Higher Education Research Promotion and National Research University Project of Thailand, Office of the Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education, Thailand.