Abstract

The uracil auxotrophic monokaryotic strain 423-9 of Lentinula edodes was crossed with nine monokaryons (cro2-2-9, W66-1, xd2-3-2, QingKe 20A, 241-1-1, 9015-1, L66-2, 241-1-2, and Qing 23A) derived from wild type strains of L. edodes. Nine dikaryotic hybrids were established from these crosses. These hybrids were fruited and 496 single spore isolates were obtained. Among these single spore isolates, 166 were identified as monokaryons under a microscope. We screened these monokaryons on selective medium and obtained 19 uracil auxotrophic monokaryons. By using the Monkaryon-monkaryon crossing method among the uracil auxotrophic monokaryons, 56 uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains were established on selective medium. These dikaryotic strains were unable to grow on minimal medium without uracil and exhibited slow growth rates on PDA plates compared to the wild type strain. The uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains also showed more vigorous growth on sawdust cultivation medium containing uracil than that without uracil. The fruiting tests showed that they formed normal fruiting bodies on the sawdust medium containing uracil. The results show that the uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strain of L. edodes could be produced by mating, and will provide a valuable resource for future genetic studies and for spawn protection and identification.

Introduction

Lentinula edodes is one of the most important edible fungi in China. It is considered a medicinal mushroom in some forms of traditional medicine (Dong et al. 2005). Both the development of cultivation techniques and commercial production of L. edodes greatly depend on the spawn. Breeding of this fungus requires long-term investment of considerable manpower, money, and time. Due to the ability to asexually reproduce desirable cultivars, the production process of L. edodes is highly reproducible. However, this type of reproduction can easily lead to spawns spreading rapidly without legal constraints, which could compromise the intellectual property rights of the breeder (Li 2007).

Auxotrophy is the inability of an organism to synthesize a particular organic compound required for its growth. A strain is said to be auxotrophic if it carries a mutation that renders it unable to synthesize an essential compound. If the nutritional requirement of the strain is not met, it cannot grow well on a minimal medium without additional nutrition. Consequently, the reproduction process will be interrupted, which can protect the breeder’s intellectual property.

L. edodes is a popular type of edible fungus among consumers. The presence of an auxotrophic genetic marker makes its cultivation and breeding more secure (Zhao et al. 2007). Our laboratory has previously succeeded in obtaining an uracil auxotrophic monokaryon (Wang et al. 2014). That strain was unable to synthesize uracil and therefore unable to grow on minimal medium without uracil supplementation.

The main selective auxotrophic markers in fungi are those that require adenine, methionine, uracil (Kim et al. 1999), tryptophan (Mishra and Tatum 1973), arginine (Chen et al. 2011), leucine (Liu et al. 2006), inositol (Xie et al. 2004), and proline (Wang et al. 2001) for growth on artificial media. In genetic studies of L. edodes, the pyrF and pyrG genes, which encode two key enzymes in the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway, have been successfully cloned (Yamagishi et al. 1996). This provides a basis for further research into the uracil auxotroph of L. edodes. Therefore, with the aim of protecting breeders’ intellectual property and future genetics research of this mushroom, the present study was conducted to establish a method of spawn breeding involving isolation by a routine separation method to develop an auxotrophic strain that cannot grow well without nutrient supplementation.

Materials and Methods

Strains, media, and growth conditions

The uracil auxotrophic monokaryotic strain of L. edodes 423-9 was obtained by UV mutagenesis of protoplasts.

The following media were employed for mycelia growth: Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA): 200 g/L potatoes, 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L agar; Potato Dextrose Agar containing uracil (PDAU): PDA containing 0.05 mmol/L uracil; Potato Dextrose (PD): 200 g/L potatoes, 20 g/L glucose; Minimal medium (MM): KH2PO3 1.0 g/L, (NH4)2HPO3 1.5 g/L, MgSO4 · 7H2O 0.3 g/L, Thiamine HCL 500 μg/L, agar15 g/L; Minimal medium containing uracil (MMU): MM containing 0.05 mmol/L uracil; Minimal medium containing uracil and 5′-FOA (MMUF): MM containing 0.05 mmol/L uracil, 0.5 g/L 5′FOA. All the media were sterilized for 15 mins at 121°C. Fifteen milliliters of each media was poured into individual plastic Petri dishes with a 9 cm diameter. The mycelia were kept in a dark room at 25°C for 1–2 w.

The spores were germinated on PDA medium and kept in a dark room at 25°C for 2 w.

The dikaryotic hybrids were inoculated onto sterile sawdust cultivation bags for producing fruiting bodies. The sawdust substrate was composed of 8:2 mixtures of oak sawdust and rice bran, including 63% water content (Lee et al. 2012). The sawdust cultivation bags were incubated at 25°C to 30°C for 3 months.

Selection of parental strains for crossing experiments

The uracil auxotrophic monokaryotic strain of L. edodes 423-9 was crossed with nine monokaryons (cro2-2-9, W66- 1, xd2-3-2, QingKe 20A, 241-1-1, 9015-1, L66-2, 241-1-2, and Qing 23A) derived from wild type strains of L. edodes. Nine dikaryotic hybrids (Z1, Z2, Z3, Z4, Z5, Z6, Z7, Z8, and Z9) were obtained from crossing tests and cultivated to produce fruiting bodies (Table 1).

Table 1

The uracil auxotrophic monokaryotic strain of

L. edodes 423-9 crossed with nine monokaryons derived from wild type

L. edodes

| F1 |

P |

| Z1 |

423-9 × cro2-2-9 |

| Z2 |

423-9 × W66-1 |

| Z3 |

423-9 × xd2-3-2 |

| Z4 |

423-9 × QingKe 20A |

| Z5 |

423-9 × 241-1-1 |

| Z6 |

423-9 × 9015-1 |

| Z7 |

423-9 × L66-2 |

| Z8 |

423-9 × 241-1-2 |

| Z9 |

423-9 × Qing 23A |

Mature, large, thick, disease- and insect-pest-free fruiting bodies of Z1–Z9 were collected to prepare spore prints.

The spores were collected in Eppendorf tubes filled with sterile water and serially diluted with sterile water until 2–3 spores were visible in a single field of view under a microscope. Spore dilution samples were spread on the PDA plate at 25°C for incubation (Zhang et al. 2002). The spores were allowed to germinate for 2 w.

Microscopic observation

Selected single colonies were transferred to PDA medium and incubated for 7 d. For each selected colony, it was further purified by transferring a small mycelia block from the edge of the colony and placing it in the center of a new PDA plate. After 10 d of incubation, mycelia were observed under a microscope, and monokaryons and dikaryons were distinguished by clamp connection.

Uracil auxotrophic mutant selection

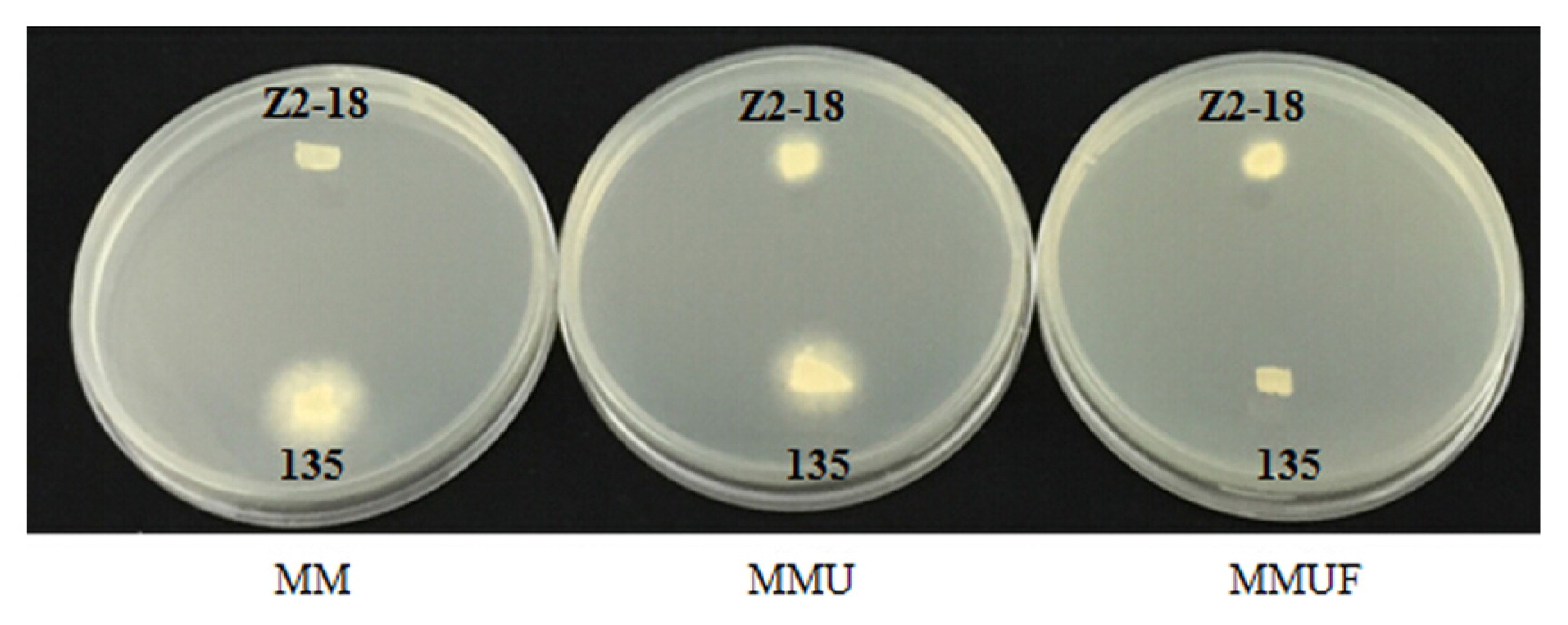

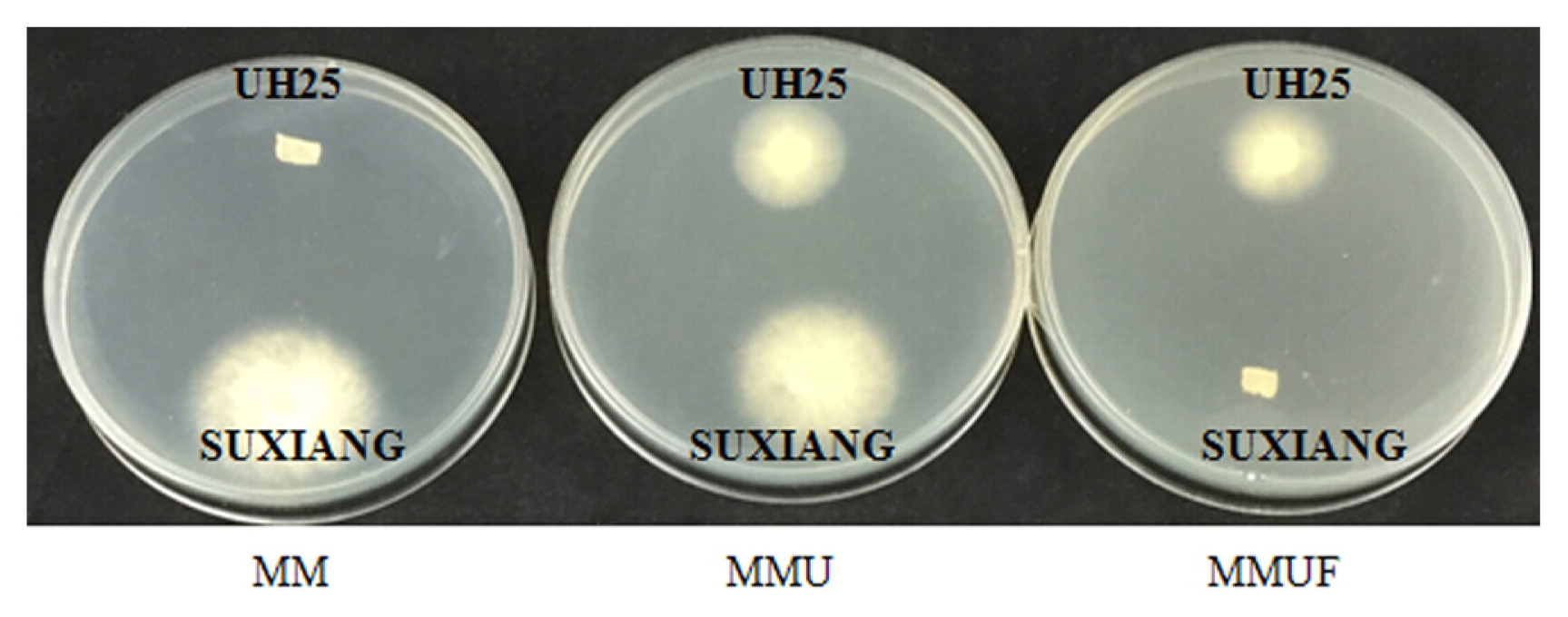

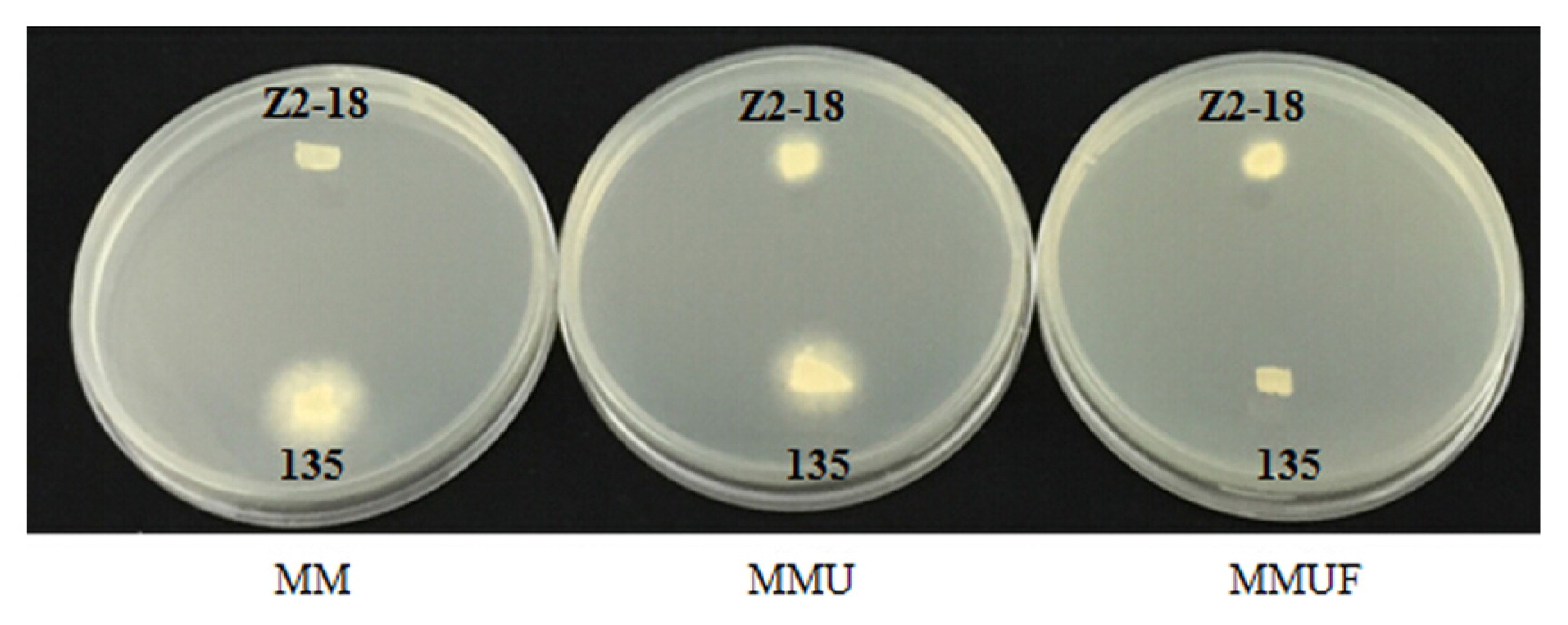

Fresh inocula from the margins of monokaryotic colonies were transferred to MM, MMU, and MMUF plates, respectively, for selecting the uracil auxotrophic mutant. The uracil auxotrophic mutants were identified based on whether they could grow well on MMU and MMUF but could not grow on MM.

Monkaryon-monkaryon (Mon-Mon) crossing method

Small pieces of mycelia from two uracil auxotrophic monokaryons were placed side by side on MMU plates for mon-mon mating. The uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains were identified based on the detection of clamp connections after fusion between hyphae of different monokaryons.

Genomic DNA preparation

All strains were cultivated in 100 ml of PD medium at 25°C for 10 d with constant shaking (150 rpm). Fungal mycelia were harvested using sterile cloth and washed twice with sterile water. Preparation of genomic DNA was performed using a method described previously (Zhang et al. 2006).

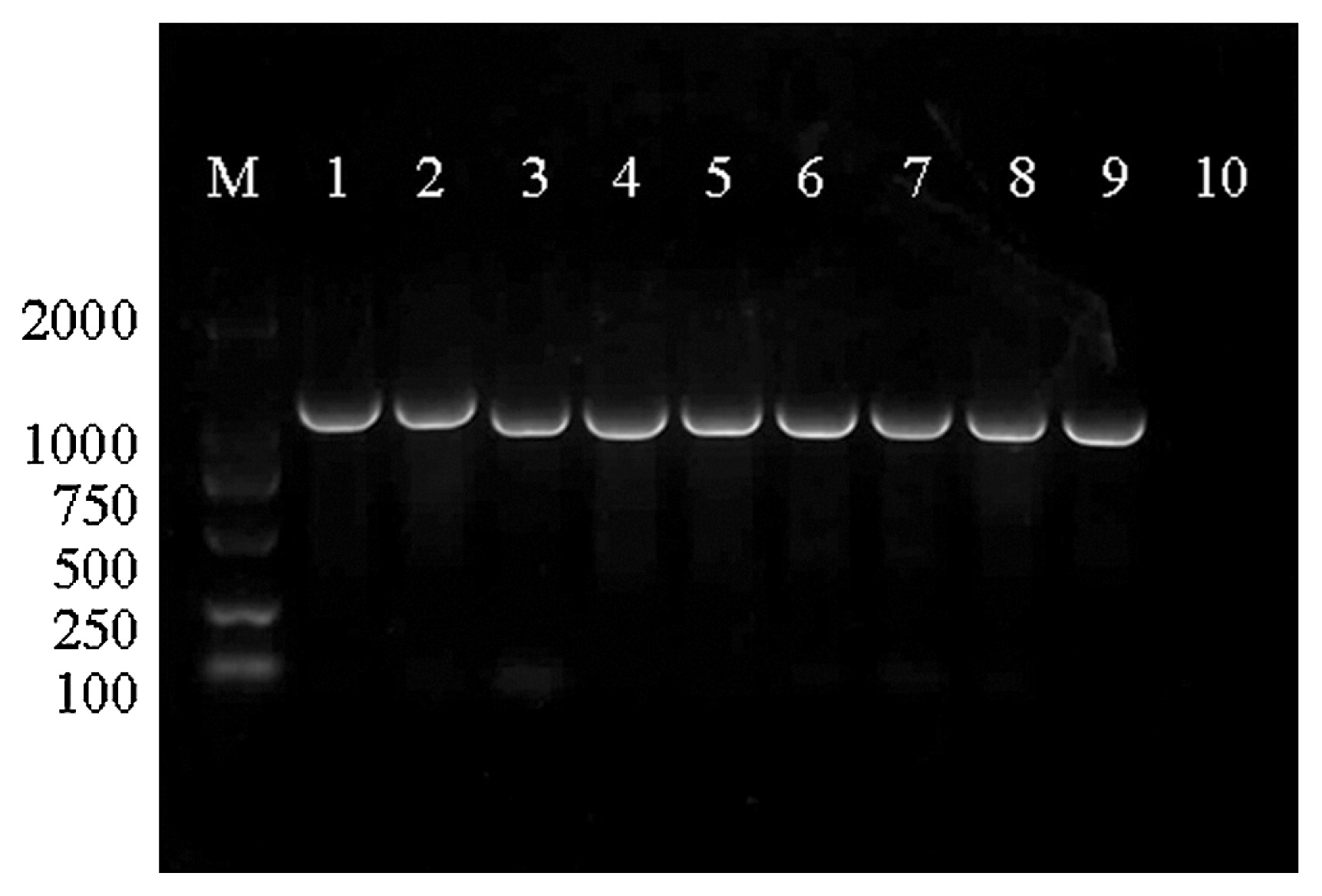

PCR testing

Detection of the pyrF gene (GenBank: KJ934231.1) was conducted using primers LEpyrF-F1150 and LEpyrF-R1150 (Table 2). Amplification included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 75 s, and a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min.

Table 2

The primers to amplify the

pyrF gene

| Gene |

Primer |

Sequence (5′-3′) |

| pyrF |

LEpyrF-F1150 |

CGCTTTATCTTTTATCTCGTGCTCAT |

|

LEpyrF-R1150 |

GAACGGTGTAGTAAGACAGGTAGTCA |

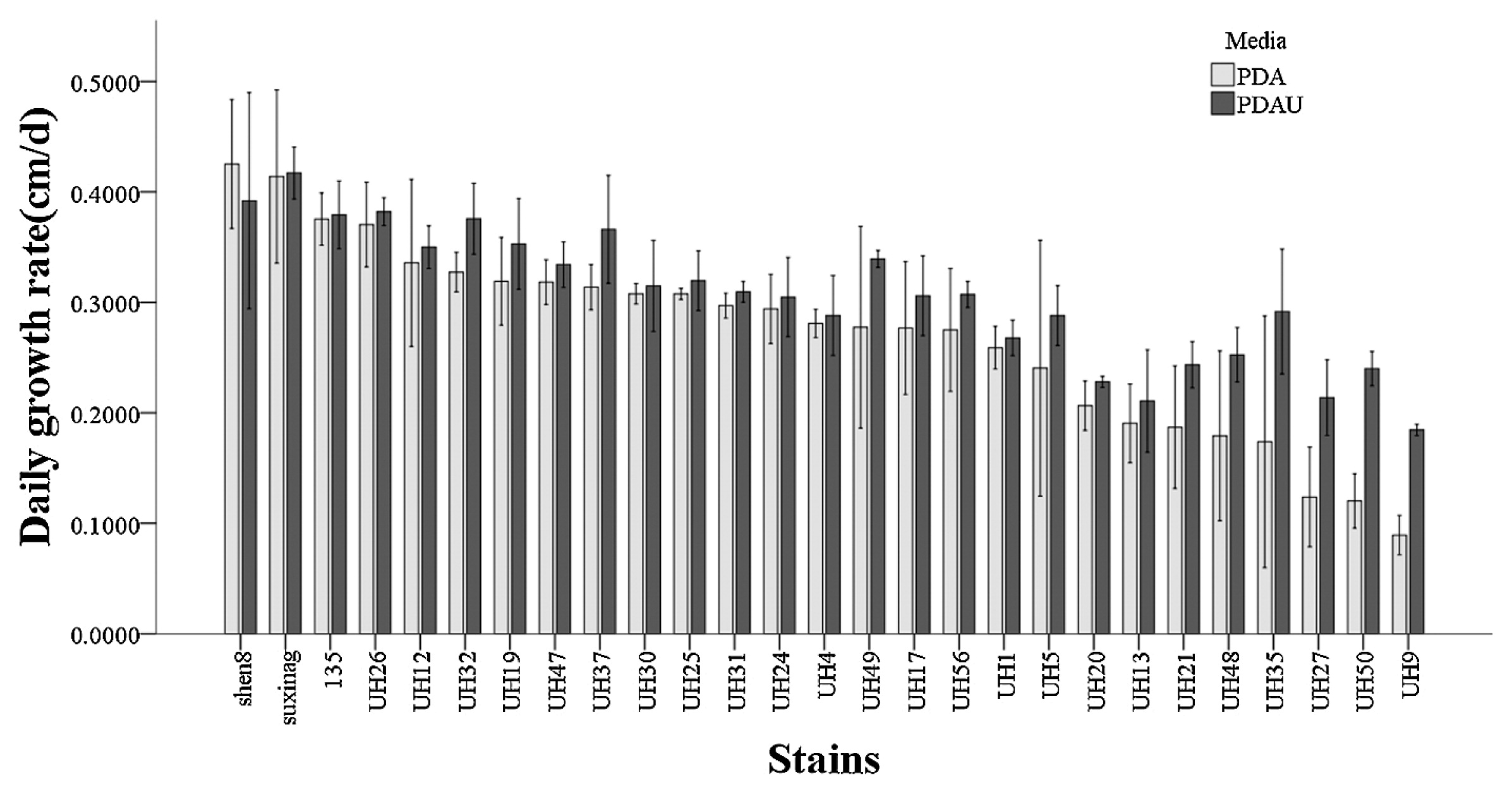

Tested strains were incubated on PDA plates and PDAU plates, and the mycelial growth rate was measured 7 d later.

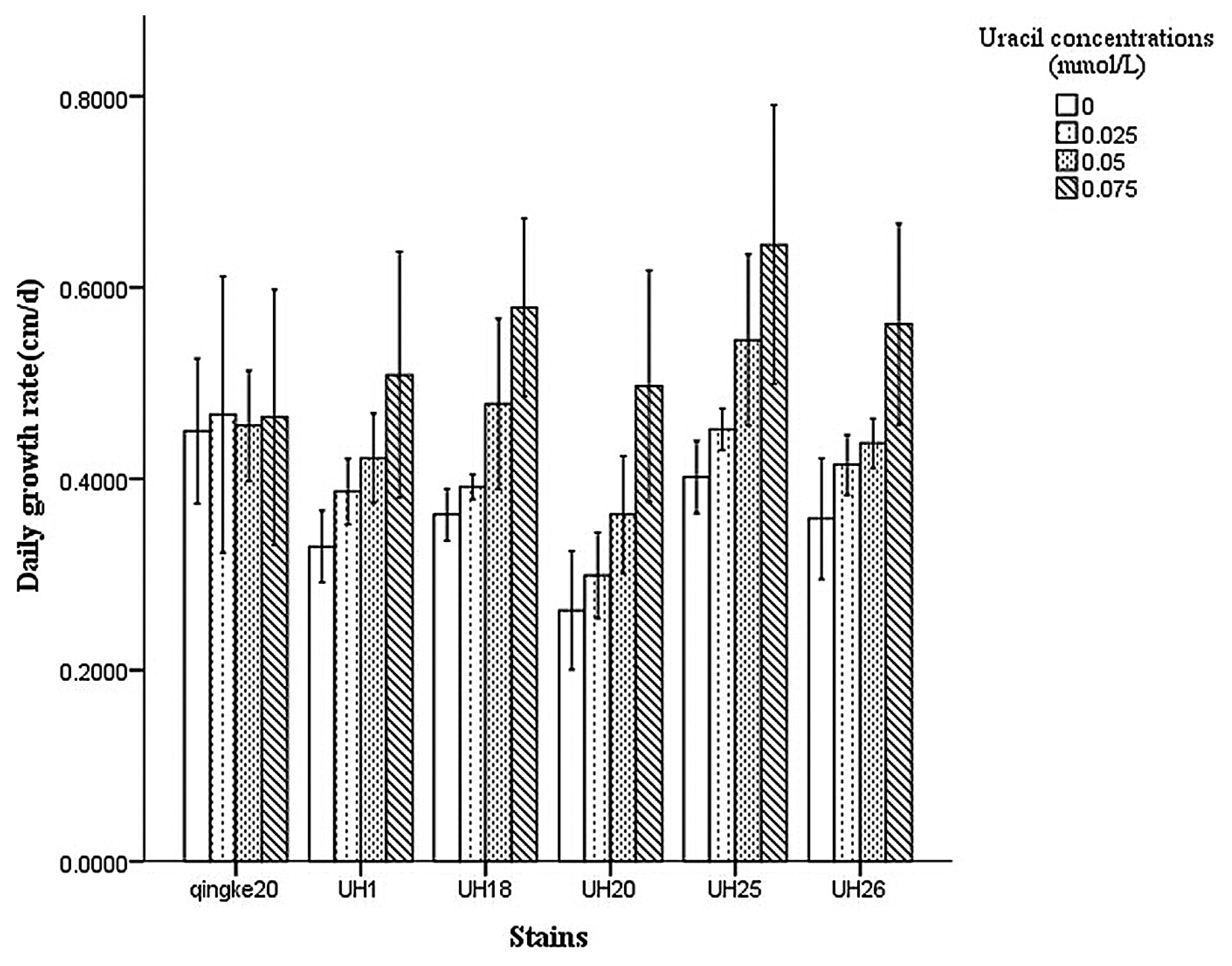

The dikaryotic strains were also incubated in test tubes filled with sawdust cultivation medium which contained various concentrations of Uracil (0, 0.025, 0.05, 0.075 mmol/L), and the mycelial growth rate was measured 15 d later.

Fruiting test

Five uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains were selected at random for fruiting tests. The dikaryotic stains were inoculated onto sterile sawdust cultivation bags, and the media were supplemented with uracil (0.075 mmol/L).

Results

The collected spores from newly generated dikaryons Z2, Z3, Z5, Z6, Z7, and Z8 germinated while those of Z1, Z4, and Z9 did not. Four hundred and ninety-six single colonies were picked after the spores were germinated on PDA medium. After 10 d of incubation, mycelia from these single spores were observed under a microscope, and monokaryons and dikaryons were distinguished by the existence of clamp connections. From the 496 colonies, 166 monokaryons and 330 dikaryons were identified. These monokaryons were screened on selective medium, and 19 uracil auxotrophic monokaryotic strains (Z2-13, Z2-14, Z2-15, Z2-18, Z2-77, Z2-97, Z3-1, Z3-2, Z3-3, Z3-4, Z3-6, Z3-7, Z3-8, Z3-27, Z3-41, Z3-42, Z5-25, Z6-9, and Z7-11) were obtained (Fig. 1). The proportion of uracil auxotroph monokaryotic strains was therefore 11.4%.

Mon-Mon mating among the above-mentioned 19 uracil auxotrophic monokaryotic strains was performed. Finally, 56 new dikaryons (UH1-UH56) were established and identified based on the detection of clamp connections under a microscope after the fusion between hyphae of different monokaryons (Fig. 2). By checking the selection media (MM, MMU, and MMUF), all 56 crossing dikaryons were uracil auxotrophy (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 4, the pyrF gene in the uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains completely corresponded with that of the parent strain 423-9, which has an 83 bp deletion in the pyrF gene.

The uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains exhibited slower growth rates on PDA plates compared to wild type strains (Fig. 5), but exhibited vigorous growth on PDAU plates. The growth rate of wild type strains was similar on PDAU plates compared to PDA plates (Fig. 6). The uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains also showed more vigorous growth on sawdust cultivation medium containing uracil than that without uracil. The growth rate of wild type strains was similar on cultivation medium containing various concentrations of uracil (Fig. 7).

The fruiting tests of the 5 uracil auxotrophic dikaryotic strains (UH1, UH18, UH20, UH25, UH26) showed that they all formed normal fruiting bodies (Fig. 8) on the sawdust medium containing uracil.

Discussion

In this study, we obtained 56 uracil auxotrophic dikaryons by using the Mon-Mon crossing method. All five strains produced fruiting bodies. The results suggested that uracil auxotrophy was stable during sexual development and could be transferred to target strains with advantageous traits by mating. On the other hand, the testing results showed these auxotrophic strains exhibited retarded growth rates on PDA medium compared to the wild type strains but exhibited a range of higher growth rates on PDAU medium. These characteristics of the auxotrophic strains could provide three potential values for spawn protection and identification. First, the uracil auxotrophy represents a new type of molecular marker to track strains and spawns, which may give breeders a powerful piece of evidence to protect their cultivars. Second, the auxotrophy phenotype provides a simply way to help growers determine whether the strain was contaminated based on its growth rates on the PDA and MM media. The contaminations by used spawns of L. edodes in commercial production have brought great losses to the farmers in China every year. Third, the auxotrophy will only exhibit normal growth on the sawdust cultivation medium containing the corresponding nutrition, such as uracil in this study, provided by the breeders. The potential advantages this auxotrophic marker may provide may enhance breeders’ enthusiasm to breed more new varieties of mushrooms. In addition, the establishment of this and other auxotrophic markers should enhance genetic research on this important edible fungus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jianping Xu for helpful comments and reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Agricultural Commission, P. R. China (Hu Nong Ke Gong Zi 2016 No.6-1-3) and National Engineering Research Center of Edible Fungi [grant number 16DZ2281300].

Literature Cited

- Chen, X.B., X.Y. Luo, S.R. Zhang and P. Zhang (2011) Screening of a L-arginine producing mutant (D-Argr) with a proline auxotroph. J. Beijing Chem. Technol. Univ. (Nat. Sci.). 38: 83–86.

- Dong, X.Y., A.H. Ning, J. Cao and M. Huang (2005) On progress of the research on lentinus edodes (berk) sing. and the pharmacological effect. J. Dalian Univ. 26: 26–29.

- Kim, B.G., Y. Magae, Y.B. Yoo and S.T. Kwon (1999) Isolation and transformation of uracil auxotrophs of the edible basidiomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 181: 225–228.

- Lee, H.Y., E.J. Ham, Y.J. Yoo, E.S. Kim, K.K. Shim, M.K. Kim and C.D. Koo (2012) Effects of aeration of sawdust cultivation bags on hyphal growth of lentinula edodes. Mycobiology 40: 164–167.

- Li, J. (2007) The analysis of Chinese edible fungus’ intellectual property protection and status. CHINA INVENTION & PATENT 8: 48–49.

- Liu, J.J., X.Y. Zhao, P.W. Li, Y.J. Tian and J.X. Zhang (2006) Screening of producing L-leucine brevibacterium flavum mutant with L-isoleucine and methionine auxotroph. China Food Add. 4: 123–128.

- Mishra, N.C. and E.L. Tatum (1973) Non-mendelian inheritance of DNA-induced inositol independence in Neurospora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70: 3875–3879.

- Wang, L.H., W.J. Mao and D.P. Bao (2014) Selected and molecular verification for uracil auxotrophic mutants of Lentinula edodes. Acta Agric. Shanghai 30: 6–9.

- Wang, P.W., D.C. Wang and L.I. Yu (2001) Advances of genetic engineering in edible mushroom. J. Jilin Agric. Univ. 23: 23–27.

- Xie, B.G., H. Zhu, Y.J. Jiang, Y.B. Rao and J.G. Zheng (2004) Mutation inducing of tremella fuciformis and screening of auxotrophic mutants. Acta Jiangxi Agric. Univ. 26: 246–249.

- Yamagishi, A., T. Tanimoto, T. Suzuki and T. Oshima (1996) Pyrimidine biosynthesis genes (pyre and pyrf) of an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62: 2191–2194.

- Zhang, H., L.H. Qin, Q. Tan and Y.J. Pan (2006) Extract genomic dna from lentinula edodes using ctab method. J. Shanghai Univ. 12: 547–550.

- Zhang, S.C., Y.Q. Cao, F. Chi, Y. Zhang and B. Zhang (2002) Researches on crossbreeding of the new strain no.1363 of lentinus edodes. Edible Fungi of China 21: 40–41.

- Zhao, X.S., J.F. Lin and J. Wang (2007) Advances in the development of biosafe selective markers for transgenic edible fungi. Acta Edulis Fungi 14: 55–61.