2017 年 67 巻 5 号 p. 459-465

2017 年 67 巻 5 号 p. 459-465

Growing resistant cultivars is the best method of protecting the crops against Potato virus Y (PVY). There are a few sources of PVY resistance/tolerance in tobacco acquired through mass selection, X-ray induced mutagenesis and introgressions from wild Nicotiana species. Here, we compare major sources of PVY resistance/tolerance in inoculation tests using ten PVY isolates collected in Central Europe (Poland and Germany) and differing with their virulence. The diversity of collected isolates was confirmed by DAS-ELISA tests and two PCR assays targeting the most common recombination sites in the PVY genome. We used these isolates in inoculation tests on five resistant cultivars ‘V.SCR’, ‘PBD6’, ‘TN86’, ‘VAM’, ‘Wiślica’, a tolerant breeding line ‘BPA’ and four susceptible cultivars ‘BP-210’, ‘K326’, ‘NC95’, ‘Samsun H’. None of the tested cultivars/breeding lines showed universal resistance against all ten isolates. However, ‘VAM’ and ‘Wiślica’ appeared to be the most effective sources, as they showed no symptoms and gave negative DAS-ELISA tests for four out of ten tested PVY isolates. In contrast, tolerance of the breeding line ‘BPA’ was effective against all tested isolates, because inoculation did not lead to development of full disease symptoms in that breeding line.

Potato virus Y (PVY) is one of the most important pathogens of solanaceous plants, such as potato, tobacco, pepper and ornamental plants, leading to significant losses of the crop (Scholthof et al. 2011). In tobacco, PVY causes symptoms ranging from mild mottling to severe leaf vein necrosis, depending on a virus strain (Brunt et al. 1996, Doroszewska et al. 2013). PVY is transmitted by more than 50 aphid species in a non-persistent manner, therefore limiting the spread of the virus by means of insecticides is not effective. The disease can be prevented by growing resistant cultivars, avoiding tobacco cultivation in the neighborhood of other solanaceous crops and removing weeds which may be a source of infection.

One of the resistant cultivars, ‘VAM’, was acquired by X-ray induced mutagenesis from the cultivar ‘Virgin A’ (Koelle 1958). The resistance factor present in ‘VAM’, called va gene, has been widely used in tobacco breeding. However, allelic forms of this gene were also acquired in other breeding programs by mass selection or/and crossings with locally produced breeding lines. Three recessive alleles of va gene were distinguished in tobacco cultivars: va0, va1, va2 of which va0 is the most efficient and present in ‘VAM’ while va2 is the weakest and present in ‘Virginia SCR’ (Ano et al. 1995). Julio et al. (2015) proved that va resistance is related to a deletion of an eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) located on chromosome 21. The same authors also showed lack of amplification of the marker associated with eIF4E for over 70% of resistant tobacco accessions. Moreover, all tobacco cultivars grown commercially contain the va gene (Verrier and Doroszewska 2002). Therefore, it is the most commonly used resistance factor in tobacco breeding for PVY resistance.

A single, widely used resistance gene is not sufficient to protect tobacco crop from PVY which is a highly variable virus. The PVY genome mutates very fast due to an error-prone RNA polymerase, lack of repair mechanisms and frequent recombination events (Blanchard et al. 2008). Recombination is well documented for two PVY strains occurring in potato and tobacco: PVYO and PVYN (Karasev and Gray 2013, Quenouille et al. 2013). The new recombinant strains, named PVYNW and PVYNTN, increased in frequency in Europe gradually replacing original strains. The more virulent recombinants, belonging to PVYNTN group and capable of overcoming the va type of resistance, have been reported in Europe (e.g. Lacroix et al. 2010).

Alternative sources of resistance can be sought among wild Nicotiana species that show resistance to PVY. For example, N. africana appeared to be immune to diverse PVY strains (Doroszewska and Depta 2011, Lucas et al. 1980). Therefore, a few attempts have been made to transfer PVY resistance from this species to cultivated tobacco. Wernsman (1992) obtained a doubled-haploid chromosome addition line ‘NC 152’ (2n = 50) containing a pair of homologous chromosomes from N. africana from a cross of this wild species with the susceptible tobacco cultivar ‘McNair 944’. Then, Lewis (2005) used backcrossing and tissue culture to stimulate transfer of resistance genes to tobacco genome. Chromosomal region Nafr introgressed into the tobacco genome had a significant effect on reducing necrotic effects of infection with severe PVY isolates, although it did not provide a complete resistance (Lewis 2007).

Independently, Doroszewska (2010) initiated a breeding program by crossing N. africana with the susceptible tobacco cultivar ‘BP-210’. The subsequent chromosome doubling of the F1 hybrid, backcrossing to the susceptible parent and self pollinations led to acquiring a stable breeding line ‘BPA’ (2n = 48). This breeding line shows tolerance to PVY because inoculated plants do not develop full disease symptoms (vein necrosis), although the virus can be detected in their tissues using serological methods.

The aim of this study is to compare the effectiveness of va resistance of five different cultivars with tolerance of the breeding line ‘BPA’ by means of inoculation tests under controlled conditions using the same set of diverse PVY isolates obtained in Central Europe. To ensure diversity of the used PVY isolates, we characterized them using serological and molecular methods.

Ten tobacco accessions were used for inoculation tests. Five of them described as resistant to PVY include:

Resistance of the above-mentioned tobacco cultivars is assumed to be determined by different alleles of the va gene: the most efficient allele va0 present in ‘VAM’; allele va1 – in ‘TN86’ and ‘Wiślica’; and the weakest allele va2 present in cultivars ‘V.SCR’ and ‘PBD6’ (Ano et al. 1995, Lacroix et al. 2010).

The next accession included in this study is the tolerant breeding line ‘BPA’ originating from crossing a susceptible tobacco (N. tabacum) with the resistant wild species N. africana (Doroszewska 2010). The remaining four cultivars used in this study were susceptible to PVY (flue cured cultivars: ‘BP-210’, ‘K326’, ‘NC95’ and the oriental cultivar ‘Samsun H’).

Plants of all above-mentioned accessions were germinated and then transplanted into trays with individual wells. When the plants reached a stage of 3–4 leaves, they were again transplanted into individual 0.6L pots filled with peat based compost. Six plants from each tested cultivar/breeding line were subjected to virus inoculations at a stage of 5–6 leaves. The whole experiment was carried out in a greenhouse under natural sunlight conditions. Plants were kept spaced out on the greenhouse tables so that there was no physical contact between them.

Serological characterization of PVY isolatesTen isolates used in this study were obtained from Poland and Germany as part of the CORESTA PVY collaborative experiment (continuation of the project described by Verrier and Doroszewska 2002, Doroszewska et al. 2017). All isolates were multiplied in ‘Samusn H’ which is susceptible to PVY and resistant to Tobacco mosaic virus. The isolates were characterized serologically in DAS-ELISA (Double Antibody Sandwich Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay) tests using two types of antibodies supplied by Bioreba:

DAS-ELISA tests were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. The value of absorbance was measured at 405 nm. Infected plants of susceptible cultivar ‘Samsun H’ were used as positive control. Plants which were not inoculated constituted negative control. Cut-off level for distinguishing positive and negative results was set according to Bioreba document on ELISA Data Analysis (http://www.bioreba.ch/files/Tecnical_Info/ELISA_Data_Analysis.pdf). The absorbance values of samples from each micro-titer plate were sorted in ascending order and visualized in a histogram. The values in the histogram increase linearly up to a point called “a step” after which the increase is no longer linear and much higher values (including positive control) can be found. Cut-off value was calculated on basis of mean value and standard deviation(s) of absorbance of samples up to the step using the following formula: cut-off = (mean + 3s) × 1.1. Values exceeding the calculated cut-off were considered positive.

Molecular characterization of PVY isolatesTotal RNA was isolated from 100 mg of infected leaf material per sample using RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). Two reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) methods were used in order to classify the collected PVY isolates into commonly occurring virus strains.

Method 1 was developed by Weilguny and Singh (1998) to distinguish PVYNTN strains from other PVYN strains. This is a 3-primer PCR targeting P1 protein in PVY genome. The presence of a 388 bp band indicates that the tested isolate belongs to PVYNTN.

Method 2 was developed by Chikh Ali et al. (2010). It is a twelve primer procedure targeting all major recombination sites in PVY genome. Interpretation of results of this PCR can be summarized as follows: band 1307 bp amplifies in strains PVYN, PVYNTN and North-American PVYN; band 853 bp amplifies in strains PVYNW and PVYO; band 441 bp amplifies in strains PVYNTN, PVYNW and Syrian recombinant strains. PCR product of size 633 bp can be used to further distinguish recombinant classes within strains PVYNTN and PVYNW; it amplifies in the recombinant group denoted as (A) which have entire P1 region similar to PVYN strain. PCR fragment 633 bp does not amplify in recombinants (B) which have additional recombination creating mosaic structure of P1 region, where N-terminal part of this region resembles PVYO strain and the rest- PVYN strain.

Method of Chikh Ali et al. (2010) allows also for amplification of bands 278 and 1076 bp specific for at least some Syrian isolates, band 532 bp amplifying only strain PVYO and band 398 bp specific for strain PVYN.

Reverse transcription in both methods was performed in a total volume of 20 μl containing: 2 μg of total RNA, 0.5 mM each of the dNTPs (Roche), 5 mM DTT (dithiothreitol, Invitrogen), 40 units of RNase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific), 200 units of SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and 1x First Strand Buffer (supplied with the reverse transcriptase). In method 1, primer no.: 1 (Weilguny and Singh 1998) was used in a concentration of 5 μM, while in method 2, oligo (dT)18 was used in a concentration of 2.5 μM. Incubation conditions were set according to manufacturer’s recommendation for the used reverse transcriptase.

After cDNA synthesis, in method 1, PCR was carried out in a volume of 20 μl containing: 1 μl of cDNA acquired in the previous step, 0.5 mM each of the dNTPs (Roche), 0.5 μM of each of the primers number 3 and 4 (Weilguny and Singh 1998), 1.5 units of DreamTaq polymerase (Thermo Scientific) and 1x DreamTaq Green Buffer supplied with the polymerase. In PCR thermal profile initial denaturation of 95°C for 2 min was followed by 36 cycles of: 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 63°C and 1 min at 72°C. Then final extension at 72°C lasted for 10 min.

After cDNA synthesis, in method 2, PCR was carried out in a volume of 25 μl containing: 1 μl of cDNA acquired in the previous step, 0.2 mM of each of the dNTPs (Roche), 1.5 units of DreamTaq polymerase (Thermo Scientific) and 1x DreamTaq Green Buffer supplied with the polymerase. Sequences and concentrations of 12 primers as well as PCR thermal profile used in this assay followed methodology of Chikh Ali et al. (2010).

All PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gel next to GeneRuler 100 bp DNA ladder (Thermo Scientific). Sizing of the PCR product, was done using software BIO 1D++ (Vilber Lourmat, France).

Inoculation testsAll ten isolates were multiplied using ‘Samsun H’. Leaves with visible disease symptoms were ground with mortar and pestle sets (separate set for each isolate). Then ground plant material was squeezed through gauze to obtain plant sap constituting inoculum. The inoculation was done as follows: the leaves of experimental plants (six from each cultivar/breeding line) were sprinkled with carborundum and then inoculum was rubbed into the leaf surface using a sponge. Inoculated leaves were then sprinkled with distilled water and sheltered from a direct sunlight for 48 hours. Four weeks after inoculation, symptoms were recorded and all experimental plants were sampled for DAS-ELISA tests with monoclonal antibodies MoAbs antiY (catalogue no.: IgG112911; Bioreba) done following manufacturer’s protocol and using the same cut-off level as described for serological characterization of PVY isolates. Plants with no clear vein necrosis symptoms were observed for additional four weeks and then subjected to another DAS-ELISA test with the same antibodies. The above-mentioned inoculation experiment was carried out twice, in the spring and summer of 2014. The results of these experiments were consistent.

Amplification of marker for susceptibility in va locusMarker S10760 is associated with eIF4E gene which is deleted in cultivars carrying va resistance (Julio et al. 2015). We amplified this marker in 10 tobacco accessions used in this study together with Nicotiana africana. PCR amplification was carried out in a 10 μl volume containing 6 μl of the True Allele Premix (Applied Biosystems), 1.5 pmol of each of the primers (S10760-E1-F and S10760-E1-2R) and approx. 20 ng of DNA. PCR was conducted on a C1000 thermal cycler (BioRad) using the following protocol: 95°C 10 min, 45 cycles of 95°C 1 min, 64°C 1 min, 72°C 2 min, followed by the final extension of 7 min at 72°C. PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gel next to GeneRuler 100 bp DNA ladder (Thermo Scientific). Sizing of the PCR product, was done using software BIO 1D++ (Vilber Lourmat, France).

Four tested isolates (IUNG no.: 4, 13, 16, 19) gave positive results of DAS-ELISA test recognizing PVYN isolates. Detection of 388 bp band in RT-PCR method 1 confirmed their assignment to the most virulent isolates within this group: PVYNTN (Table 1). These results were further confirmed using method 2 by the amplification of PCR fragments 441 and 1307 bp and the absence of PCR fragment 853 bp. Moreover, the detection of 633 bp product, associated with a recombination of P1 protein, supported assignment of these four isolates to the group PVYNTN (A) (Table 1).

| PVY isolate | DAS-ELISA | PCR products amplified using: | Assignment to PVY strains according to classification used by Chikh Ali et al. (2010) | Assignment to PVY strains according to classification used by Green et al. (2017)c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 (Weilguny and Singh 1998)a | Method 2 (Chikh Ali et al. 2010)b | ||||||||

| MoAbs antiY IgG | MoAbs antiYN IgG | 388 bp | 1307 bp | 853 bp | 633 bp | 441 bp | |||

| IUNG 17 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | PVYNW (B) | nd |

| IUNG 7 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | PVYNW (B) | PVY261-4 |

| IUNG 3 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | PVYNW (B) | PVYN-Wi |

| IUNG 18 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | PVYNW (B) | nd |

| IUNG 2 | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | PVYNW (B) | PVYN-Wi |

| IUNG 14 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | PVYNW (A) | PVYN:O |

| IUNG 16 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | PVYNTN (A) | nd |

| IUNG 4 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | PVYNTN (A) | PVYNTNa |

| IUNG 13 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | PVYNTN (A) | PVYNTNa |

| IUNG 19 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | PVYNTN (A) | nd |

nd – no data available.

The remaining six isolates (IUNG no.: 2, 3, 7, 14, 17, 18) gave negative result in DAS-ELISA test with antibodies directed against coat protein typical for PVYN strains and did not amplify 388 bp band specific for PVYNTN (Table 1). Moreover, in method 2, they amplified 441 bp band – common for all recombinant strains and 853 bp band – specific for PVYNW strains (Table 1). Therefore, these six isolates belong to PVYNW group. Moreover, isolate IUNG 14 amplified 633 bp band specific for recombination within P1 protein, therefore recombinant PVYNW (A) was present in this isolate. This band was absent in the remaining five PVYNW isolates, therefore they can be classified as recombinants PVYNW (B).

Results of inoculations testsSymptoms induced by PVY isolates on susceptible cultivars included: severe vein necrosis sometimes extending to stems, and also involved chlorotic spots and vein clearing. The highest resistance was demonstrated by ‘VAM’ and ‘Wiślica’, which showed no symptoms and had no virus detected in their tissues in DAS-ELISA tests after inoculation with four isolates from PVYNW strain. However, more virulent isolates from PVYNTN strain were able to break resistance of these cultivars. ‘TN86’, carrying resistance derived from ‘VAM’, appeared to be less resistant to PVY than the latter (Table 2). ‘TN86’ showed complete resistance (as manifested by the lack of symptoms and a negative DAS-ELISA test) against only three isolates. ‘V.SCR’ and ‘PBD6’ are even less effective sources of resistance, because most isolates caused severe disease symptoms on these cultivars. None of the tested isolates, not even PVYNTN, induced veinal necrosis symptoms on ‘BPA’. Only mild symptoms of chlorotic spots and vein clearing were observed on that breeding line (Table 2). Such results combined with the positive DAS-ELISA test can indicate PVY tolerance of ‘BPA’.

| Cultivar/breeding line | ‘VAM’ | ‘Wiślica’ | ‘TN86’ | ‘V.SCR’ | ‘PBD6’ | ‘BPA’ | ‘BP-210’ | ‘K326’ | ‘NC95’ | ‘Samsun H’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | |||||||||||

| PVYNW | IUNG 17 | NS | NS | NS | NS | VC | CS | VN | VN | VN | VN |

| IUNG 7 | NS | NS | NS | VC | VN | VC, CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

| IUNG 3 | NS | NS | NS | VN | VN | VC, CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

| IUNG 18 | NS | NS | VN | VN | VN | CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

| IUNG 2 | NS | VN | NS | VC | VN | VC, CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

| IUNG 14 | CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

| PVYNTN | IUNG 16 | VN | VN | VN | VN | VN | VC, CS | VN | VN | VN | VN |

| IUNG 4 | VN | VN | VN | VN | VN | CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

| IUNG 13 | VC, CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

| IUNG 19 | VN | VN | VN | VN | VN | CS | VN | VN | VN | VN | |

Grey cells indicate positive results of DAS-ELISA tests (PVY detected in the leaves).

Symptoms: NS – no symptoms; VC – vein clearing; CS – chlorotic spots on a leaf lamina; VN – vein necrosis.

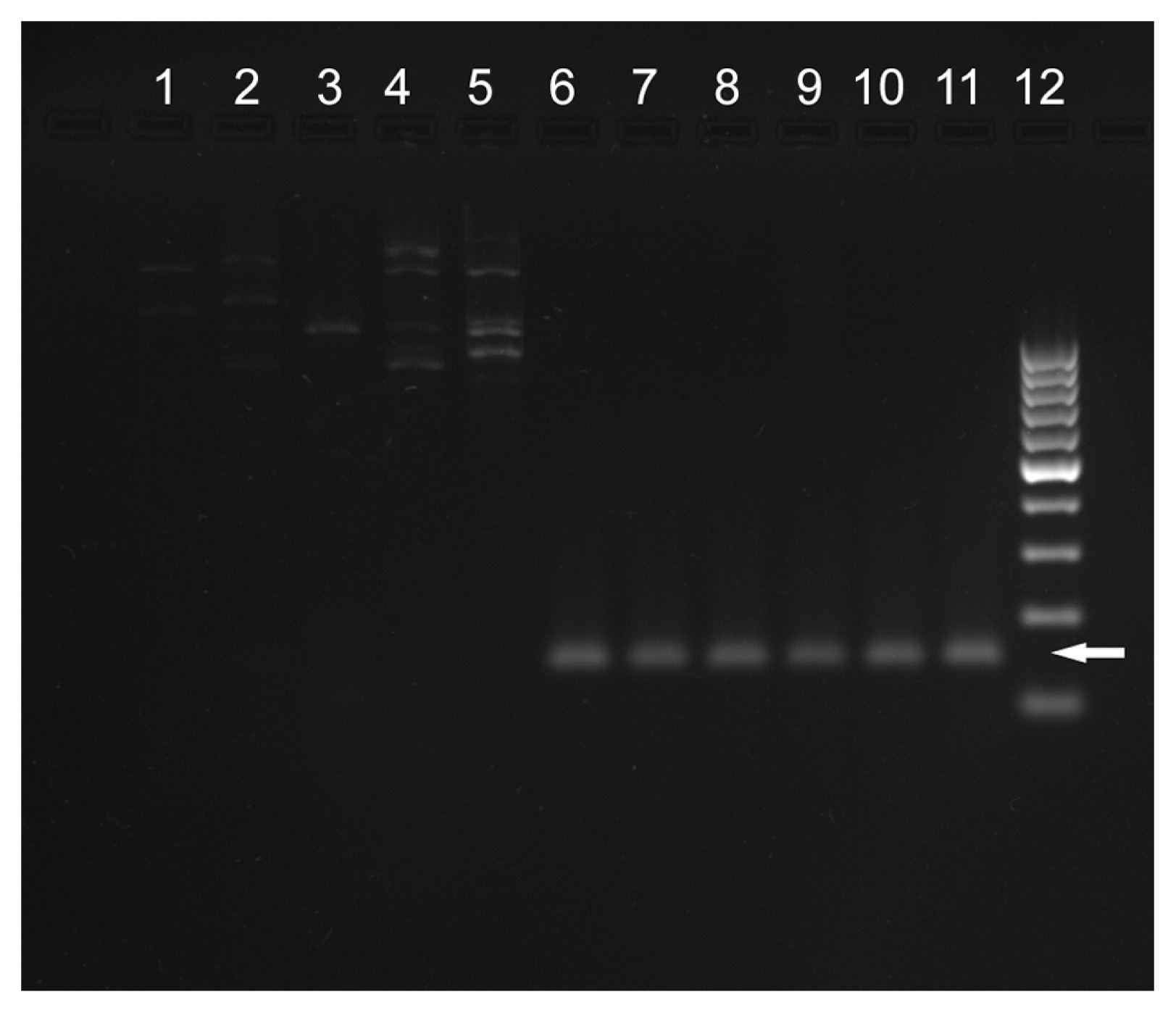

None of the five resistant cultivars used in this study amplified marker S10760, while ‘BPA’, susceptible cultivars and N. africana amplified a PCR product of expected size (Fig. 1).

Amplification of marker S10760 in 10 tobacco accessions used in this study. 1: ‘VAM’, 2: ‘Wiślica’, 3: ‘TN86’, 4: ‘V.SCR’, 5: ‘PBD6’, 6: ‘BPA’, 7: ‘BP-210’, 8: ‘K326’, 9: ‘NC95’, 10: ‘Samsun H’, 11: Nicotiana africana, 12: GeneRuler 100 bp DNA ladder (Thermo Fisher). Arrow indicates expected size of S10760 marker (150 bp).

We performed resistance tests on tobacco accessions using ten diverse virus isolates which were thoroughly characterized by serological (DAS-ELISA) and molecular (RT-PCR) methods targeting major recombination sites in the virus genome. Four of the PVY isolates were assigned to a more virulent group of recombinant virus strains (PVYNTN) and the remaining six – to the less virulent group (PVYNW). This assignment to different groups of PVY strains could be verified on the sequence level for six out of ten isolates characterized in this paper (IUNG 2, 3, 4, 7, 13, 14) because they were sequenced before by Przybys et al. (2013; Genbank accession numbers between JF927750 and JF927762). Phylogenetic analysis based on the full-length PVY sequence from these six isolates and 82 sequences obtained from Genbank confirmed division of the studied isolates into PVYNW and PVYNTN strains (unpublished data). Moreover, within PVYNW type B group, the sequence obtained from isolate IUNG7 showed the highest similarity to the German isolate Wilga 261-4 (accession no.: AM113988), while sequences of isolates IUNG2 and IUNG3 clustered together with the German isolate Wilga 5 (accession no.: AJ890350; Schubert et al. 2007). Isolate IUNG14 was similar to the UK isolate SASA207 and North American isolate L-56 belonging to PVYNW type A (PVYN:O) group (accession nos.: AJ584851 and AY745492, respectively; Lorenzen et al. 2006). Within PVYNTN group, the sequence of isolates IUNG4 and IUNG13 showed the highest similarity to North American isolate EF026075 and Hungarian isolate M95491, respectively (Baldauf et al. 2006, Thole et al. 1993). Recent phylogenetic study of PVY included sequences of most of the above-mentioned isolates (Green et al. 2017). Following updated classification used by these authors, our isolates can be assigned to at least four groups of PVY strains: PVY261-4, PVYN-Wi, PVYN:O, PVYNTNa (Table 1). To sum up, the molecular and serological characterization confirmed the diversity of PVY isolates used in this study.

The inoculation tests with PVYNTN isolates showed that each of the five cultivars carrying va gene developed disease symptoms and had high levels of the virus in their tissues detectable with DAS-ELISA test. The differences in effectiveness of the PVY resistance of these cultivars were shown only in the case of inoculation with less virulent PVYNW strains. The order of decreasing effectiveness of resistance for these five cultivars, based on severity of symptoms and the result of serological tests, is as follows: ‘VAM’, ‘Wiślica’, ‘TN86’, ‘VSCR’ and ‘PBD6’. Generally, this result is consistent with the observations collected in the worldwide field trials performed over the years 1996–2011 (Doroszewska et al. 2017, Verrier and Doroszewska 2002).

Our inoculation tests show differences in the way that the cultivars, which are assumed to carry the same va allele, respond to PVY. For example, ‘Wiślica’ and ‘TN86’ are assumed to carry the same va1 allele, although the resistance of the first cultivar was less frequently broken by the virus in our experiment (Table 2). The resistance of ‘TN86’ is weaker than that of ‘VAM’, although it was derived from the latter. That difference, observed also in other studies, is attributed to differences in the genetic background of these two cultivars (Verrier and Doroszewska 2002).

In contrast to the five tested va resistance sources, ‘BPA’ did not develop full disease symptoms (vein necrosis) even after inoculation with the most virulent PVYNTN strains. Nevertheless, the virus could be detected in its leaves. Such results indicate tolerance of ‘BPA’. The genetic determination of this tolerance is independent of the deletion of eIF4E gene, what is proved by the positive result of amplification of S10760 marker (Fig. 1). PVY tolerance of ‘BPA’ originates from the wild species N. africana, the species itself being completely immune to the virus (Doroszewska and Depta 2011, Lucas et al. 1980). The fact that, instead of complete resistance, only tolerance was successfully transferred from this species to cultivated tobacco by Doroszewska (2010) suggests that the PVY resistance of N. africana can be determined by more than one gene. A similar conclusion was reached by Lewis (2007), who also pointed out two explanations for lower resistance of breeding lines carrying Narf chromosomal fragment introgressed from N. africana compared to the resistance showed by the wild species: either resistance in N. africana is controlled by multiple genes on more than one chromosome or the introgressed resistance functions differently in the N. tabaccum genetic background.

The tolerance of ‘BPA’ does not stop PVY from multiplying within the plant but it prevents development of full disease symptoms even in contact with the most virulent PVYNTN strains, therefore it may prevent the loss of the crop. Combining tolerance of ‘BPA’ with va resistance would be a promising objective of next breeding efforts aiming at developing a cultivar that would be able to cope with a wider range of PVY strains.

This research was financially supported by the National Science Centre of Poland (project no.: 2011/03/B/NZ9/04746). We thank Dr. Norbert Billenkamp for providing PVY isolates from Germany and Prof. Apoloniusz Berbeć for helpful comments on the final version of the manuscript.