Abstract

A new super-hard rice cultivar, ‘Chikushi-kona 85’, which was derived from a cross between ‘Fukei 2032’ and ‘EM129’, was developed via bulk method breeding. ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ showed a higher content of resistant starch than the normal non-glutinous rice cultivar, ‘Nishihomare’, and a higher grain yield than the first super-hard rice cultivar, ‘EM10’. The amylopectin chain length of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ and its progenitor line ‘EM129’ was longer than that of ‘Nishihomare’, and was similar to that of ‘EM10’. This suggests that the starch property of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was inherited from ‘EM129’, which is a mutant line deficient in a starch branching enzyme similar to ‘EM10’. Genetic analysis of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ crossed with ‘Nishihomare’ also showed that the starch property of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was regulated by a single recessive gene. Consumption of processed cookies made from ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ flour showed a distinctive effect in controlling blood sugar levels in comparison to the normal non-glutinous rice cultivar ‘Hinohikari’. These results show that ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ is a novel genetic source to develop new products made of rice, which could reduce calorie intake and contribute to additional health benefits.

Introduction

In Japan, rice consumption has been steadily declining since 1960 due to Westernization of lifestyle accompanied by an increase in consumption of other foods rich in starch such as bread, noodles, and pasta. Therefore, to boost rice consumption, it is immensely important to develop rice and its products qualitatively. Recently, several new rice cultivars used for rice flour have been developed. ‘Mizuhochikara’ (Sakai 2010) has been used for making bread and distilled liquor and ‘Koshinomenjiman’ (Ishizaki et al. 2011) for making Japanese udon noodles. Although these cultivars are favored in rice flour markets in Japan, the total production of rice flour has steadily decreased since 2011, when it was at its highest with 36,842 t, to 18,352 t in 2014. These data suggest that the demand for rice flour as an alternative to wheat flour has already been met and novel benefits of rice flour must be sought to increase consumption.

Meanwhile, diabetes mellitus has been growing as a serious condition among the Japanese population; 27.3% of the male and 21.8% of the female population are classified as being either diagnosed with diabetes mellitus or as being prediabetic (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan 2014). As a result, medical costs have increased in order to provide proper care and treatment for these patients. Subsequently, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare proposed guidelines of desirable eating habits for Japanese people to prevent diabetes. Controlling calorie intake is one of the important ways to maintain good eating habits. One of the ways to do this is to consume low-calorie food.

‘EM10’ was developed by Kyushu University, Japan, by mutation breeding using N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (Nishi et al. 2001, Satoh and Oomura 1979, Takahashi et al. 2001). This cultivar was called super-hard rice because ‘EM10’ contains a substantial amount of resistant starch (Ohtsubo et al. 2006) and its starch is difficult to be digested by the human body. Grains of ‘EM10’ are opaque, and its starch property is totally different from that of conventional non-glutinous rice cultivars; the amylopectin chain length of ‘EM10’ is longer than that of the wild-type cultivar ‘Kinmaze’ (Nishi et al. 2001). This specific characteristic of ‘EM10’ is due to the lack of activity of the branching enzyme IIb, which corresponds to the amylose-extender gene (Mizuno et al. 1993, Nishi et al. 2001). Using rice flour of ‘EM10’, it was attempted to develop wheat/rice bread and noodles (Nakamura et al. 2010) and tempura flour (Nakamura and Ohtsubo 2010). Although ‘EM10’ was quite promising, its yield is low (60–70% of the wild-type cultivar ‘Kinmaze’), which labeled ‘EM10’ as not being suitable for commercial production for the rice market.

The aim of this study was to develop a super-hard rice cultivar, which is suitable for rice flour production and also shows a high yield. We successfully developed a promising cultivar, named ‘Chikushi-kona 85’.

Materials and Methods

Breeding process

The genealogy of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ is shown in Fig. 1. The maternal cultivar, ‘Fukei 2032’, is a non-glutinous japonica cultivar with a high yield, developed in Fukuoka Agricultural Research Center. The paternal cultivar, ‘EM129’, is a super-hard rice cultivar with a lower activity of the branching enzyme IIb than its wild-type cultivar ‘Kinmaze’ (Mizuno et al. 1993). ‘EM129’ also shows similar starch properties to ‘EM10’, developed by the mutation breeding method using a chemical mutagen, N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (Yano et al. 1985). The endosperm of ‘EM129’ is opaque, but its grain filling is higher than ‘EM10’ (Satoh 1985). The breeding procedure is shown in Table 1. The cross between both cultivars was carried out at Fukuoka Agricultural Research Center in 2005. Individual selection was conducted in 2010 using F4 plants focusing on the filling ratio and endosperm type (opaque or translucent) of the grains, and subsequent selections thereafter were conducted according to the pedigree method. One of the superior lines, which was harvested in 2011, was named ‘Chikushi-kona 85’, and the evaluation of its yield performance and starch properties, as well as its role in controlling blood sugar content were continuously carried out in the following years. Starch properties, except for amylopectin chain length distribution, were evaluated by Niigata Agricultural Research Institute and Torigoe Company Limited. The amylopectin chain length distribution was measured by capillary electrophoresis methods by Kyushu University. The measurement of blood sugar levels was carried out by Torigoe Company based on the evaluation method for glycemic index (Jenkins et al. 1981).

Table 1

Breeding procedure of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’

| Year |

Generation |

Breeding experiments |

Name of selected line |

| 2005 |

(crossing) |

Fukei 2032/EM129 |

|

| 2006 |

F1 |

Generation advancement |

|

| 2009 |

F2–3 |

Generation advancement |

|

| 2010 |

F4 |

Individual selection (from 256 plants) |

|

| 2011 |

F5 |

Selection of individual lines and yield trial test (from 53 lines) |

|

| 2012 |

F6 |

Yield trial test |

Chikushi-kona 85 |

| 2013 |

F7 |

Yield trial test |

|

| 2014 |

F8 |

Yield trial test |

|

| 2015 |

F9 |

Yield trial test |

|

| 2016 |

F10 |

Yield trial test |

|

Results and Discussion

Agronomic traits

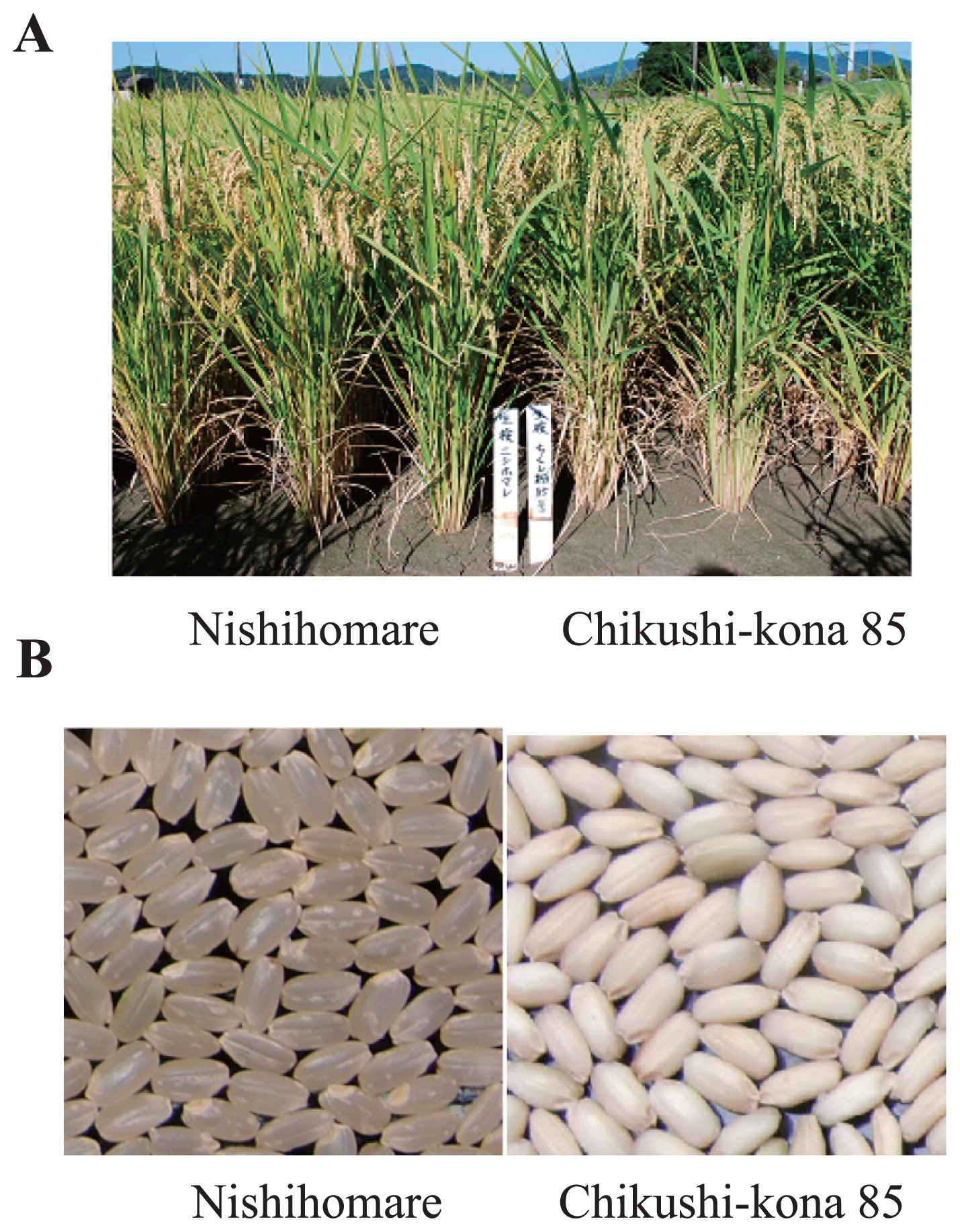

Table 2 shows the agronomic traits of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’. The heading date of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was slightly later than ‘Nishihomare’, which is a standard late-ripening cultivar in the warm regions of Japan. The culm length (83 cm) and panicle length (22.9 cm) of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ were longer than those of ‘Nishihomare’ (75 cm, 19.8 cm), but the number of panicles in ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ (303/m2) was similar to that of ‘Nishihomare’ (308/m2). The lodging degree of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was higher than that of ‘Nishihomare’. The yield of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was 4.2 kg/a lower than that of ‘Nishihomare’, but 23.1 kg/a higher than that of ‘EM10’, the first rice cultivar with resistant starch. The weight per 1000 grains of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was 1.9 g lighter than that of ‘Nishihomare’. The abortive grains ratio of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was 1.9%, which was similar to that of ‘Nishihomare’ (1.2%), and lower than that of ‘EM10’ (9.2%). The grains of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ were opaque, suggesting insufficient filling of starch in the endosperm (Fig. 2). This grain characteristic was similar to that of ‘EM10’. The field blast resistance was unknown because ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ carried an unknown true resistance gene.

Table 2

Agronomic traits of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’

a

| Cultivar |

Year |

Heading date |

Culm length (cm) |

Panicle length (cm) |

No. of panicles per unit area (No./m2) |

Lodging degreeb |

Yield (kg/a)c |

1000 grain weightc (g) |

Abortive grain (%) |

Grain quality |

| Chikushi kona 85 |

|

Sep. 5 |

83 |

22.9 |

303 |

1.2 |

47.0 |

23.3 |

1.9 |

opaque |

| Nishihomare |

2011–16 |

Sep. 1 |

75 |

19.8 |

308 |

0 |

51.2 |

25.2 |

1.2 |

translucent |

| EM10 |

|

Aug. 31 |

72 |

19.5 |

373 |

0.1 |

23.9 |

18.2 |

9.2 |

opaque |

a The evaluation of agronomic traits was conducted in Fukuoka Agriculture and Forestry Research Center. Dates of sowing seeds and transplanting seedlings were May 15 to May 21 and June 20 to June 25, respectively. The amount of total nitrogen application was 1.0 kg/a.

b Zero means plants stand erect and 5 means plants lodge completely.

c Yield and 1000-grains weight were calculated using grains screened with 1.85 mm wire cloth test sieves.

Table 3 shows the polishing properties of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’. With polishing time, the percentage of polished rice steadily decreased and the whiteness increased in both ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ and ‘Nishihomare’. ‘Nishihomare’ took 60 seconds to pass 90%; however, ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ took only 40 seconds. Nevertheless, the percentage of polished rice with the embryo of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ remained higher than that of ‘Nishihomare’. This suggests that some of the brown rice grains cracked while polishing. However, from a practical viewpoint, the loss of grains due to cracked rice did not affect the yield of the polished rice (data not shown).

Table 3

Polishing properties of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’

a

| Cultivar |

Brown rice |

Measured properties |

Polishing time (seconds) |

| Moisture content (%) |

Whitenessb |

20 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

60 |

70 |

| Chikushi-kona 85 |

15.8 |

30.3 |

Percentage of polished rice (%)c |

92.5 |

90.5 |

89.6 |

88.0 |

86.6 |

83.7 |

| Whiteness of polished riceb |

43.7 |

46.5 |

47.9 |

49.8 |

51.5 |

53.9 |

| Percentage of polished rice with embryo (%) |

79.0 |

60.3 |

15.0 |

8.3 |

5.0 |

4.8 |

| Nishihomare |

14.6 |

20.9 |

Percentage of polished rice (%)c |

92.9 |

92.0 |

91.0 |

90.2 |

89.4 |

89.1 |

| Whiteness of polished riceb |

33.6 |

35.5 |

36.1 |

37.3 |

38.4 |

39.5 |

| Percentage of polished rice with embryo (%) |

6.3 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

a Polishing machine TPII (Kett Company Limited) was used for measurement of polishing properties.

b C-300 (Kett Company Limited) was used for measurement of whiteness.

c Percentage of polished rice was calculated as follows; polished rice (g) × 100/brown rice (g).

Table 4 shows the chemical properties of the endosperm of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’. The apparent amylose content of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was higher than that of ‘Nishihomare’ and was similar to that of ‘EM10’. The polished grain of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ indicated lower gelatinization than that of ‘Nishihomare’ in 5 M urea solution. The resistant starch content of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’, which was measured by two different methods (Resistant Starch Assay Kit (Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland) and artificial digestion method (Homma et al. 2008)), was higher than that of ‘Nishihomare’ and slightly lower than that of ‘EM10’. The damaged starch content, which was measured by two different methods (Starch Damage Assay Kit (Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland) and acid solution process (Arisaka and Yoshii 1991)), was lower than that of ‘Nishihomare’. The lower content of damaged starch is preferable, otherwise it could affect the quality of post-harvest processed foods made of rice flour (Araki et al. 2009). The mean diameter of the flour of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was smaller than that of ‘Nishihomare’. A smaller flour size is preferable for post-harvest processing rice (Shoji et al. 2012). All these properties together establish that the grain of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ produced improved-quality rice flour in comparison to that of normal non-glutinous cultivars. The water absorbance of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ was higher than that of ‘Nishihomare’ because of the grain conformation of the former, as well as the endosperm of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ being opaque and containing more air space than that of ‘Nishihomare’.

Table 4

Chemical properties of endosperm and flour of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’

a

| Cultivar |

Apparent amylose content (%)b |

Starch disintegration in 5 M urea solutionc |

Resistant starch (%) |

Damaged starch (%) |

Mean diameter of flour (μm)g |

Water absorbance (%) |

| Kitd |

ADMe |

Kitd |

ASPf |

15°C

16 hr |

40°C

60 min |

| Chikushi kona 85 |

29.2 |

L |

17.4 |

22.5 |

9.5 |

5.7 |

63.8 |

40.9 |

40.4 |

| Nishihomare |

18.9 |

H |

0.3 |

13.9 |

11.4 |

6.8 |

77.9 |

30.8 |

30.2 |

| EM10 |

31.4 |

L |

25.4 |

33.4 |

8.8 |

4.5 |

66.5 |

44.4 |

43.4 |

a Rice flour was generated with pinmill SRG10A (SATAKE, Corp. Japan) and sieved with 100 mesh.

b This value was measured by Auto Analyzer (BL-TEC K. K., Osaka, Japan) based on the method of

Juliano (1971).

c This evaluation was performed based on the method

Sato et al. (2005). L and H indicate that gelatinization is low and high, respectively.

d Resistant Starch Assay Kit and Starch Damage Assay Kit (Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland).

g This value was measured with Helium-Neon Laser Optical System (Sympatec, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany).

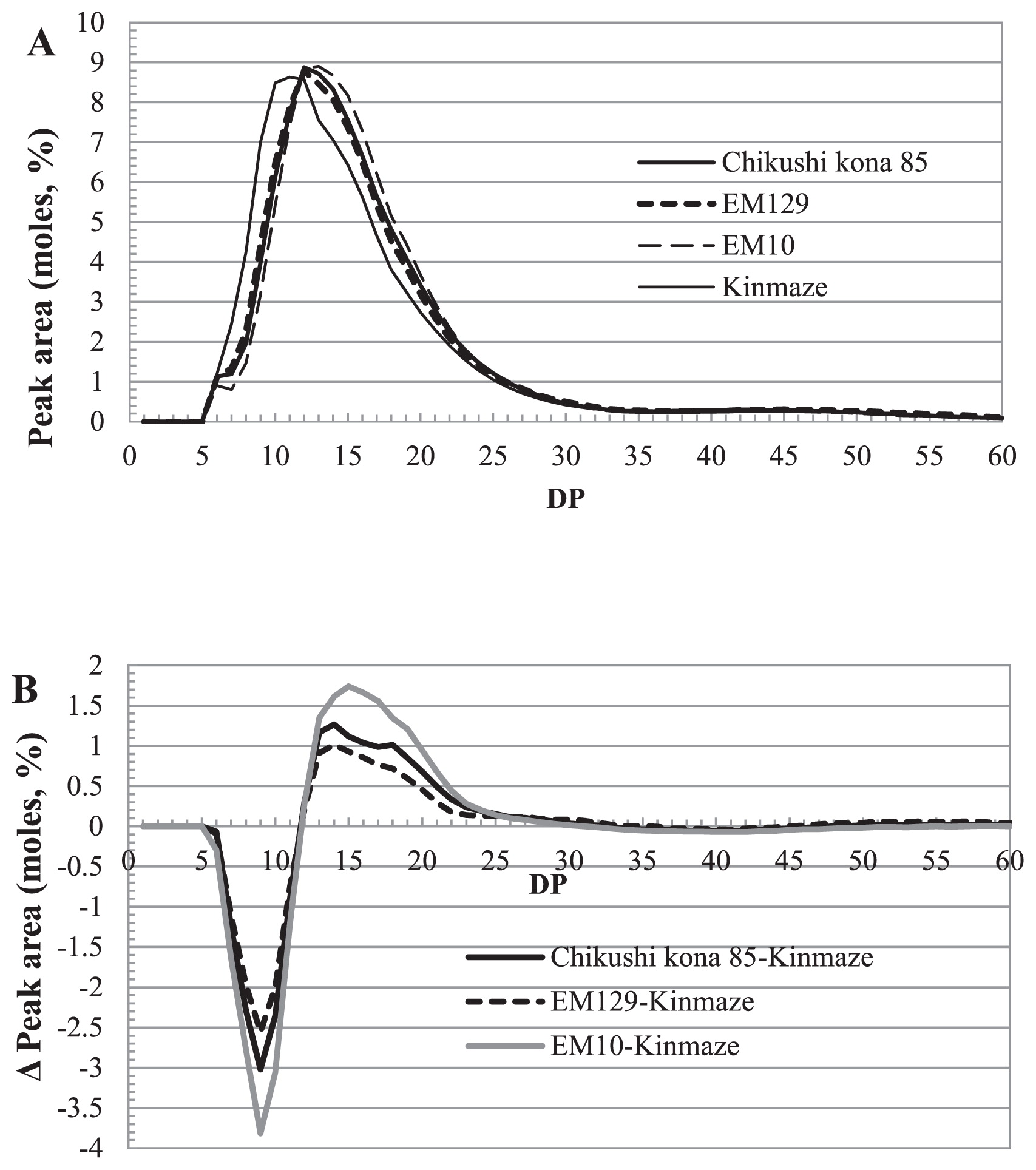

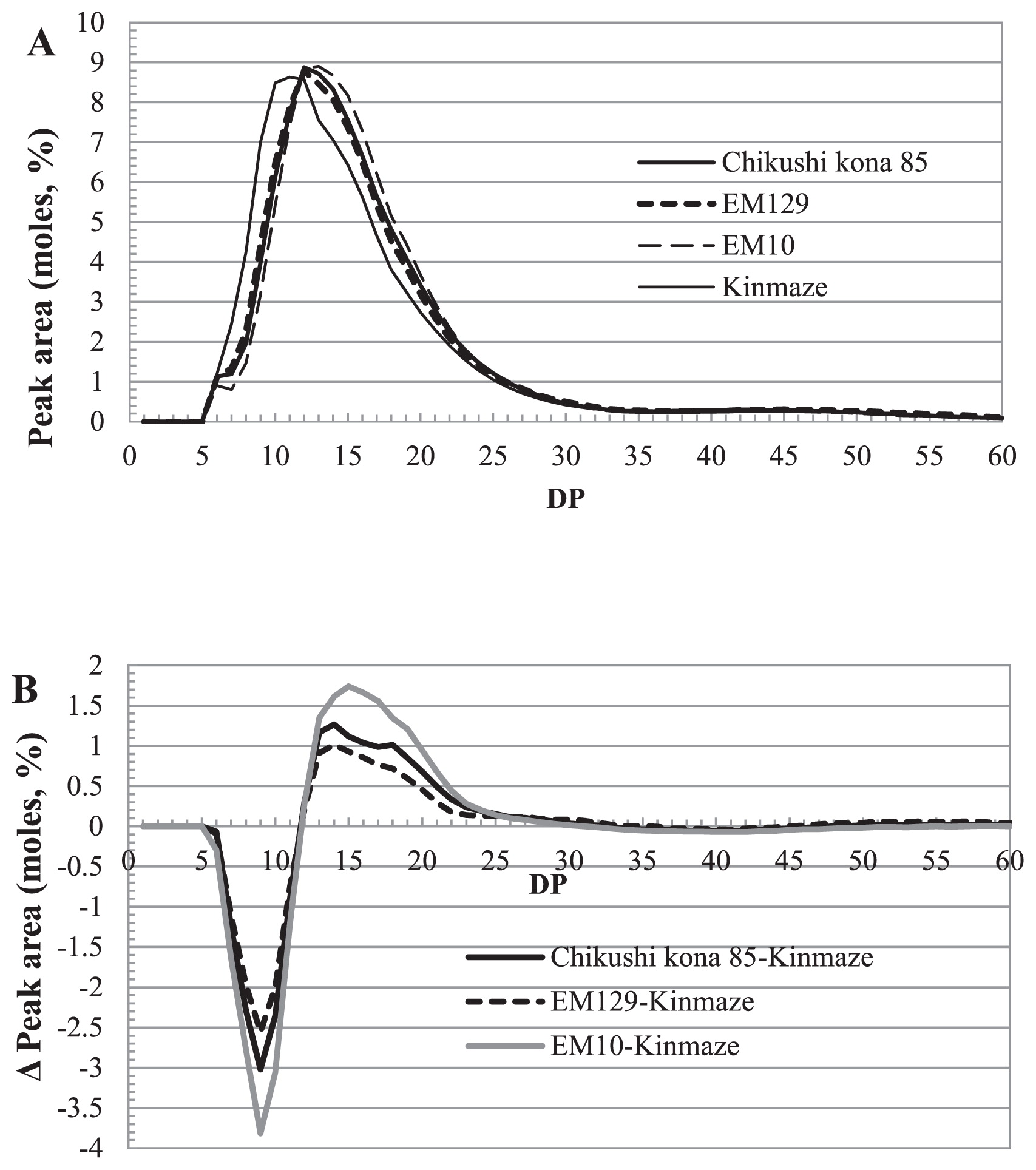

Fig. 3 indicates varietal differences in amylopectin chain length distribution of the endosperm of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’. The proportion of short chains (6 ≤ DP ≤ 11) is lower and that of intermediate chains (12 ≤ DP ≤ 28) is higher than that of the normal non-glutinous cultivar ‘Kinmaze’. These changes in amylopectin chain length might contribute to the higher value of apparent amylose content (Table 4). ‘EM129’, which is a paternal parent line of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’, and ‘EM10’ showed a similar pattern of amylopectin chain length distribution to ‘Chikushi-kona 85’, although ‘EM10’ exhibited the lowest proportion of short chains and the highest proportion of intermediate chains among these three cultivars.

Butardo et al. (2011) demonstrated that inactivation of the starch branching enzyme IIb by RNA silencing leads to an apparent high amylose content and a high ratio of amylopectin long chain. Asai et al. (2014), Tsuiki et al. (2016), and Itoh et al. (2017) also showed that the branching enzyme IIb-deficient mutant lines exhibited a similar higher apparent amylose content than normal glutinous cultivars. Furthermore, Tsuiki et al. (2016) and Itoh et al. (2017) revealed that their mutant lines also harbored a higher resistant starch content than the wild-type cultivar. These data suggest that all of the starch properties of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ were due to a lack of activity of the branching enzyme IIb.

Genetic analysis of starch properties

Table 5 shows the segregation ratio of translucent and opaque endosperms of F2 seeds derived from crosses between super-hard rice cultivars (‘Chikushi-kona 85’ and ‘EM129’) and a normal cultivar (‘Nishihomare’). As mentioned above, the grain quality of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ and ‘EM129’ were opaque. Furthermore, all crosses showed 3:1 segregation ratios of translucent and opaque grains, implying that a single recessive gene, beIIb, which corresponds to the amylose-extender gene, might be involved in the specific starch character of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ and ‘EM129’.

Table 5

Allelism test of responsible gene for specific starch properties of ‘Chikushi kona 85’ and ‘EM129’.

| No. |

Cross |

Generation |

translucent |

Opaque |

χ2 value (3:1) |

| 1 |

Chikushi kona 85/Nishihomare |

F2 |

235 |

69 |

0.44ns |

| 2 |

Nishihomare/Chikushi kona 85 |

F2 |

229 |

85 |

0.41ns |

| 3 |

Nishihomare/EM129 |

F2 |

158 |

41 |

1.15ns |

| 4 |

EM129/Nishihomare |

F2 |

182 |

55 |

0.18ns |

ns indicates that χ

2 value is not significant for expected segregation ratio.

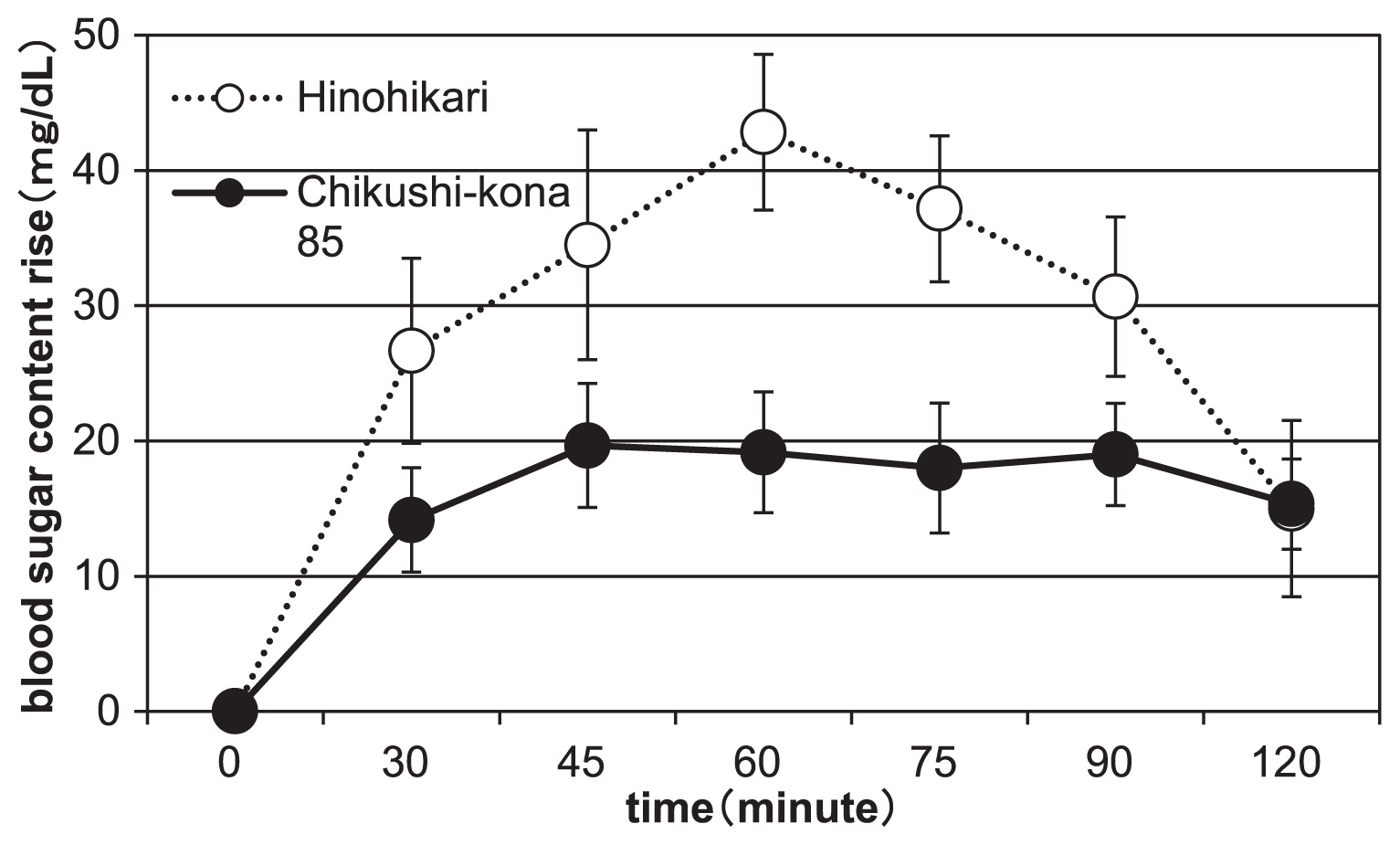

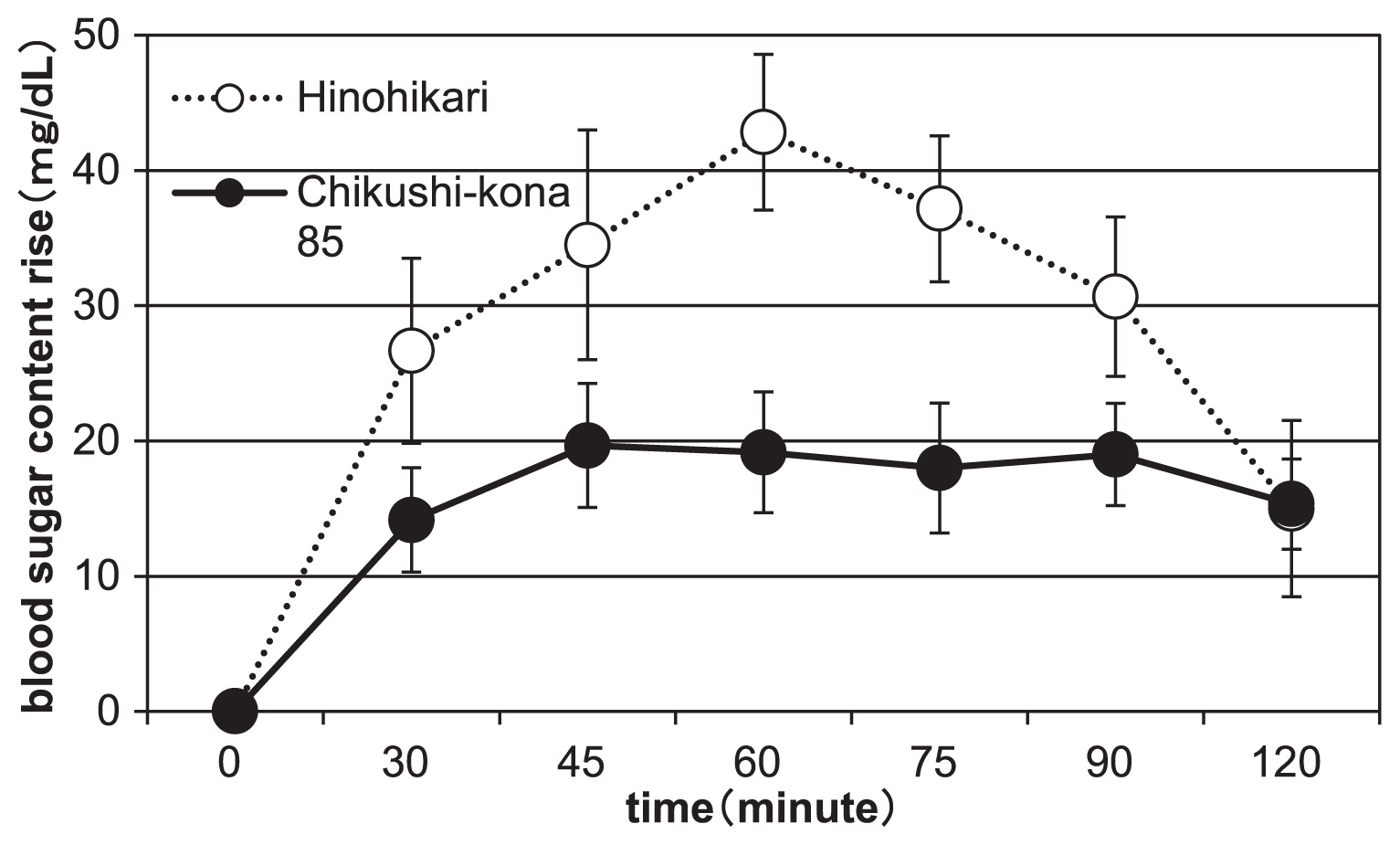

Fig. 4 shows the influence of ingestion of processed stick-type cookies (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 1) made of rice flour to the change in blood sugar levels in the human body. When thirty minutes passed after consuming cookies made of general non-glutinous cultivar ‘Hinohikari’ and super-hard cultivar ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ flour, the blood sugar levels increased to 27 mg/dL and 14 mg/dL, respectively. This shows that the rise in blood sugar levels after consuming cookies made of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ rice flour was significantly lower compared to that of the normal non-glutinous rice cultivar ‘Hinohikari’. Since rice generally has a higher glycemic index compared to other carbohydrate foods (Ludwig 2002), its over-consumption tends to lead diabetes mellitus. As shown in Fig. 4, cookies made of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ could restrict the increase in blood sugar content. This result indicates that rice products made of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ have a potential as low glycemic index foods.

As mentioned above, ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ consists of unique starch properties and has the potential to contribute toward reducing calorie intake and subsequently to prevent obesity and diabetes. On the contrary, brown rice of ‘Chikushi-kona 85’ tends to crack while polishing, and the eating quality of the cooked rice was poor and its resistant starch decomposed while being cooked in a rice cooker (data not shown). Therefore, suitable post-harvest processing methods, including one that can restrict crack of grains and the decomposition of resistant starch and maintain a positive impact on blood sugar levels, are necessary to disseminate this cultivar. This trial is now in progress and a finished product will be launched in the near future.

Itoh et al. (2017) and Tsuiki et al. (2016) pointed out that double mutant lines (beIIb + GBSSI or SSIIIa deficient) carried a higher resistant starch content than a single mutant line (only beIIb) and the resistant starch content of double mutant lines was higher than a single mutant line after cooking. This demonstrates the possibility that newly improved super-hard rice cultivars harboring stable resistant starch could be developed.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the research and development projects for application in promoting new policy at Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Japan. This study was also partly supported by Fukuoka Bio Valley project of Kurume Research Park Co., Ltd.

Literature Cited

- Araki, E., T.M. Ikeda, K. Ashida, K. Takata, M. Yanaka and S. Iida (2009) Effects of rice flour properties on specific loaf volume of one-loaf bread made from rice flour with wheat vital gluten. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 15: 439–448.

- Arisaka, M. and Y. Yoshii (1991) Measurement of damaged starch content in rice flour using acid solution process. Rep. Niigata Food Res. Inst. 26: 11–12.

- Asai, H., N. Abe, R. Matsushima, N. Crofts, N.F. Oitome, Y. Nakamura and N. Fujita (2014) Deficiencies in both starch synthase IIIa and branching enzyme IIb lead to a significant increase in amylose in SSIIa-inactive japonica rice seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 65: 5497–5507.

- Butardo, V.M., M.A. Fitzgerald, A.R. Bird, M.J. Gidley, B.M. Flanagan, O. Larroque, A.P. Resurreccion, H.K. Laidlaw, S.A. Jobling, M.K. Morell et al. (2011) Impact of down-regulation of starch branching enzyme IIb in rice by artificial microRNA- and hairpin RNA-mediated RNA silencing. J. Exp. Bot. 62: 4927–4941.

- Fujita, N., H. Hasegawa and T. Taira (2001) The isolation and characterization of a waxy mutant of diploid wheat (Triticum monococcum L.). Plant Sci. 160: 595–602.

- Homma, N., R. Akaishi, Y. Yoshii, K. Nakamura and K. Ohtsubo (2008) Measurement of resistant starch content in polished rice and processed rice products. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Tech. 55: 18–24.

- Ishizaki, K., T. Matsui, S. Kaneda, K. Kobayashi, H. Kasaneyama, S. Abe, K. Hirao and T. Hoshi (2011) A new rice cultivar “Koshinomenjiman”. J. Niigata Agri. Res. Inst. 11: 19–26.

- Itoh, Y., N. Crofts, M. Abe, Y. Hosaka and N. Fujita (2017) Characterization of the endosperm starch and the pleiotropic effects of biosynthetic enzymes on their properties in novel mutant rice lines with high resistant starch and amylose content. Plant Sci. 258: 52–60.

- Jenkins, D., T. Wolever, R.H. Taylor, H. Barker, H. Fielden, J.M. Baldwin, A.C. Bowling, H.C. Newman, A.L. Jenkins and D.V. Goff (1981) Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 34: 362–366.

- Juliano, B.O. (1971) A simplified assay for milled-rice amylose. Cereal Sci. Today 16: 334–360.

- Ludwig, D.S. (2002) The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 287: 2414–2423.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (2014) The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, 2012, p. 32.

- Mizuno, K., T. Kawasaki, H. Shimada, H. Satoh, E. Kobayashi, S. Okumura, Y. Arai and T. Baba (1993) Alteration of the structural properties of starch components by the lack of an isoform of starch branching enzyme in rice seeds. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 19084–19091.

- Nakamura, S., H. Satoh and K. Ohtsubo (2010) Palatable and bio-functional wheat/rice products developed from pre-germinated brown rice of Super-Hard Cultivar EM10. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74: 1164–1172.

- Nakamura, S. and K. Ohtsubo (2010) Influence of Physicochemical properties of rice flour on oil uptake of tempura frying batter. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74: 2484–2489.

- Nishi, A., Y. Nakamura, N. Tanaka and H. Satoh (2001) Biochemical and genetic analysis of the effects of amylose-extender mutation in rice endosperm. Plant Physiol. 127: 459–472.

- Ohtsubo, K., K. Yoza, S. Nakamura and K. Suzuki (2006) Development of processed rice product and its production method. Japan patent P2006–217813A.

- O’Shea, M.G. and M.K. Morell (1996) High resolution slab gel electrophoresis of 8-amino-1,3,6-pyrenetrisulfonic acid (APTS) tagged oligosaccharides using a DNA sequencer. Electrophoresis 17: 681–686.

- Sakai, M. (2010) A high yielding rice variety for multi-purpose use ‘Mizuhochikara’. Res. J. Food and Agri. 33: 14–17.

- Sato, H., S. Saito and T. Yoshida (2005) The hardness of glutinous rice cake, gelatinization and urea disintegration in waxy rice. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 74: 310–315.

- Satoh, H. and T. Omura (1979) Induction of mutation by the treatment of fertilized egg cell with N-methyl-N-nitrosourea in rice. J. Fac. Agr. Kyushu Univ. 24: 165–174.

- Satoh, H. (1985) Genic mutations affecting endosperm properties in rice. Report of Gamma Field Symposium 24: 17–35.

- Shoji, N., Y. Hanyu, S. Mohri, S. Hatanaka, M. Ikeda, C. Togashi and T. Fujii (2012) Evaluation of powder and hydration properties of rice flour milled by different techiniques. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Tech. 59: 192–198.

- Takahashi, H., K. Ohtsubo, M. Romero, H. Toyoshima, H. Okadome, A. Nishi and H. Satoh (2001) Evaluation of basic physical and chemical properties of amylose extender mutants of rice for the presumption of the suitable utilizations. J. Jpn. Soc. Food Sci. Tech. 48: 617–621.

- Tsuiki, K., H. Fujisawa, A. Itoh, M. Sato and N. Fujita (2016) Alterations of starch structure lead to increased resistant starch of steamed rice: Identification of high resistant starch rice lines. J. Cereal Sci. 68: 88–92.

- Yano, M., K. Okuno, J. Kawakami, H. Satoh and T. Omura (1985) High amylose mutants of rice, Oryza sativa L. Theor. Appl. Genet. 69: 253–257.