2018 Volume 68 Issue 2 Pages 242-247

2018 Volume 68 Issue 2 Pages 242-247

Oryza glumaepatula originates from South America continent and contains many valuable traits, such as tolerance to abiotic stress, high yield and good cooking qualities. However, hybrid sterility severely hindered the utilization of favorable genes of O. glumaepatula by interspecific hybridization. In order to further understand the nature of hybrid sterility between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula, a near isogenic line (NIL) was developed using a japonica variety Dianjingyou 1 as the recurrent parent and an accession of O. glumaepatula as the donor parent. A novel gene S56(t) for pollen sterility was mapped into the region between RM20797 and RM1093 on the short arm of chromosome 7, the physical distance between the two markers was about 469 kb. The genetic behavior of S56(t) followed one-locus allelic interaction model, the male gametes carrying the alleles of O. sativa in the heterozygotes were aborted completely. These results would help us clone S56(t) gene and understand the role of S56(t) in interspecific sterility.

Rice is one of the most important food crops for half of the world’s population. In the past half century, two major breakthroughs in rice breeding were made through the use of semidwarf gene and heterosis (Patnaik et al. 1990, Spielmeyer et al. 2002). But recent years, rice yields have not significantly increased, mainly due to the narrow genetic basis of the parental materials imposed by domestication and years of modern breeding program (Tanksley and McCouch 1997). The reduction of genetic diversity of the Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) occurred during the domestication from their wild progenitors. Previous reports indicated that only 10%–20% of the diversity in the wild species was retained in the Asian cultivated rice (Zhu et al. 2007), and 40% of the alleles was lost during the domestication from wild progenitor to the cultivated rice (Sun et al. 2002). Thus, there is a general belief that genes useful for improving rice productivity are contained in the wild relatives of rice, and it is an accessible approach to introduce favorable genes from the wild relatives of rice into the cultivated rice for improvement (Vaughan et al. 2003, Xiao et al. 1998).

Oryza glumaepatula Steud. is one of the wild relatives of rice distributed in the South America, sharing the same AA genome as the Asian cultivated rice. It shows many excellent traits, such as resistance to deep and flowing water, more panicle number, erect panicle, high-yielding, good cooking and milling qualities, slender grains, symbiosis with diazotrophic bacteria (Brondani et al. 2002, Junior et al. 2013, Rangel et al. 2008, Sanchez et al. 2000, Sobrizal and Yoshimura 2002, Vaughan et al. 2003, Zhang et al. 2015). Thus, the exploitation and utilization of the valuable alleles of O. glumaepatula might overcome yield bottleneck of O. sativa. However, severe interspecific hybrid sterility hampered the introduction of favorable genes from O. glumaepatula into Asian cultivated rice varieties (Naredo et al. 1998, Sano 1986). Therefore, it is important to identify more interspecific hybrid loci and discover wide compatibility genes or neutral alleles to overcome reproductive isolation (Wang et al. 2005).

Hybrid sterility is the most common form of reproductive isolation between populations and species, and plays an important role in leading genetic differentiation of species and maintaining species identity (Orr and Presgraves 2000, Sano 1986). Hybrid sterility occurs frequently in many remote crosses in rice (Oka 1957). By now, more than 50 loci for hybrid sterility have been identified in rice (Ouyang et al. 2010, Ouyang and Zhang 2013), among those, S5, Sa, S27/S28, DPL1/DPL2, hsa1 and S1 have been cloned and characterized (Chen et al. 2008, Kubo et al. 2015, Long et al. 2008, Mizuta et al. 2010, Xie et al. 2017, Yamagata et al. 2010, Yang et al. 2012). Until now, S12, S22(t), S23(t), S27(t) and S28(t) as pollen eliminators have been identified in the hybrid between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula (Sakata et al. 2014, Sano 1994, Sobrizal et al. 2000a, 2000b, 2002). The duplicated S27(t) and S28(t) loci encode a mitochondrial ribosomal protein L27, and pollen carrying both nonfunctional S27-glums and S28-T65s alleles would be sterile. Either of the fertile alleles (S27-T65+ or S28-glum+) is able to rescue the sterile phenotype in hybrids (Yamagata et al. 2010). Identifying more interspecific hybrid sterility loci between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula would help us understand evolutionary process of post-zygoutic reproductive isolation during AA genome differentiation and provide ideas for breeders to use the valuable genes of O. glumaepatula.

In order to detect the genes responsible for interspecific hybrid sterility between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula, a near isogenic line (NIL) was developed with Dianjingyou 1, a japonica cultivar, as the recurrent parent and an accession of O. glumaepatula as the donor parent. A novel gene S56(t) was mapped into the region between RM20797 and RM1093 on the short arm of chromosome 7. This result would help us understand the nature of interspecific hybrid sterility, raise the bridge parents and utilize the favorable genes from O. glumaepatula by crossing.

An O. glumaepatula accession, Acc.104386, introduced from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), as a donor and male parent, was crossed with a temperate japonica variety of O. sativa, Dianjingyou 1, from Yunnan province, P. R. China. F1 was successively backcrossed with Dianjingyou 1 as a recurrent and male parent. From BC1F1 generation, progenies with pollen fertility below 90% were selected to make backcrossing until BC8F1. From BC8F2 generation, 417 SSR markers evenly distributed on 12 chromosomes of rice were used to evaluate the substituted fragments from O. glumaepatula. The results indicated that only 5.2 cM segment on chromosome 7 and 34.7 cm segment on chromosome 6 in some individuals were substituted by O. glumaepatula genome. The individual harboring the homozygous genome fragments from O. glumaepatula was selected as NIL-S56(t). NIL-S56(t) was crossed with the recurrent parent Dianjingyou 1 to raise F1, and then was self-fertilized to produce the F2 population. Four hundred and twenty-eight individuals were used to map S56(t) for interspecific hybrid sterility between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula.

All plant materials were grown in the paddy field at the Winter Breeding Station, Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (YAAS) located in Sanya, Hainan Province, P. R. China.

Phenotype evaluationPollen grain fertility was measured using anthers collected from spikelets at 1 to 2 days before anthesis and stored in 70% ethanol (Doi et al. 1998). Four anthers from a single spikelet were mixed and stained with 1% I-KI solution. Sterile types were further classified as typical, spherical or stained abortion types, and at least 300 pollen grains were observed to evaluate the pollen fertility of each plant under three independent microscopic fields.

DNA extraction and PCR protocolThe experimental procedure for DNA extraction was performed as previously described (Edwards et al. 1991); Rice SSR markers were selected from the Gramene database (http://www.gramene.org) or previously published SSR markers in rice (McCouch et al. 2002). PCR was performed as follows: a total volume of 10 μl containing 10 ng template DNA, 1 × buffer, 0.2 μM of each primer, 50 μM of dNTPs and 0.5 unit of Taq polymerase (Tiangen Company, Beijing, China). The reaction mixture was incubated at 94°C for an initial 4 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C 30 s, 55°C 30 s and 72°C 30 s, and a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were separated on 8% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel and detected using the silver staining method.

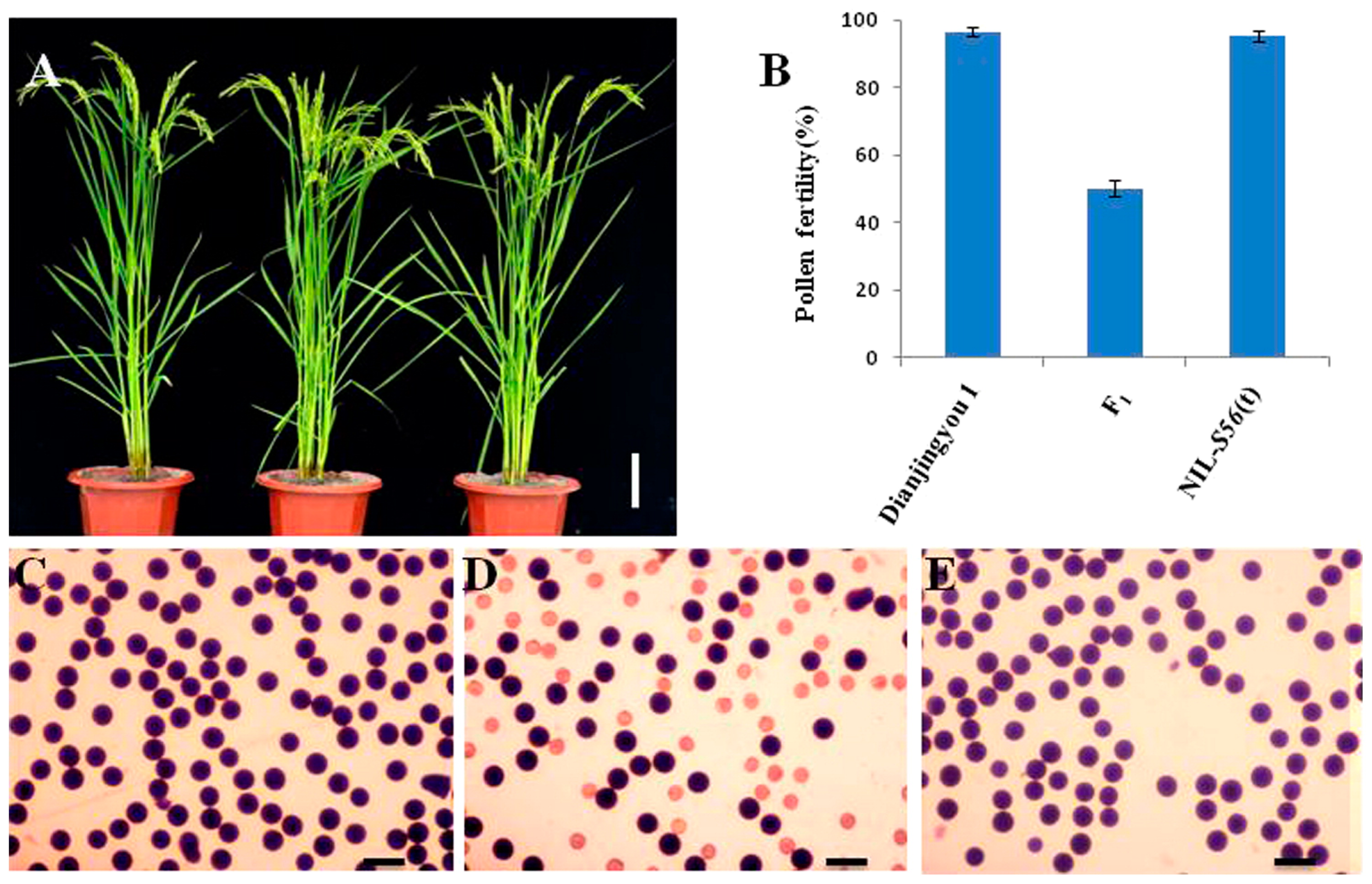

There was no significant difference in plant height, tiller number, heading date and panicle architecture among Dianjingyou 1, F1 hybrid and NIL-S56(t) (Fig. 1A). Pollen fertility of Dianjingyou 1 and NIL-S56(t) was 96.5% and 95.2%, respectively, whereas pollen fertility of F1 hybrid was significantly lower than those of two parents, and about 50% pollen grains were aborted as staining abortion (Fig. 1B–1E). In addition, it was observed that spikelet fertility in F1 hybrid was also semi-sterile (data not shown). But correlation analysis using F2 population showed that pollen fertility was not correlated with the spikelet fertility (r = 0.117), which suggested that semi-sterility in the male gamete and female gamete of F1 was controlled by different loci. This report presents the study of pollen grain sterility.

The phenotype and pollen fertility comparison of Dianjingyou 1, F1 hybrid and NIL-S56(t). A: The plant architecture showed no significant difference among Dianjingyou 1 (left), F1 hybrid (middle) and NIL-S56(t) (right), Scale bar = 10 cm; B: Pollen fertility of Dianjingyou 1, F1 hybrid and NIL-S56(t); C–E: Pollen fertility by I2-KI staining of Dianjingyou 1, F1 hybrid and NIL-S56(t), respectively, scale bar = 50 μm.

In order to understand whether S56(t) acted as a single Mendelian factor or not, pollen fertility was investigated in F1 and F2 populations derived from the cross between Dianjingyou 1 and NIL-S56(t). Pollen fertility of all the F1 individuals showed semi-sterility. Pollen fertility in the F2 population was segregated into fertile and semi-sterile classes in a 135:124 ratio, which fitted the 1:1 ratio (χ2 = 0.234, P = 0.628). This result indicated that pollen semi-sterility in F1 hybrid was controlled by only one locus. This locus was designated as S56(t).

Linkage analysis indicated that S56(t) for interspecific hybrid sterility was tightly linked with RM3394 on the short arm of chromosome 7. Homozygotes at RM3394 almost showed normal pollen fertility and pollen fertility of heterozygotes at RM3394 was significantly lower than that of homozygotes, exhibiting semi-sterility. It indicated that S56(t) for interspecific hybrid sterility located near RM3394 (Table 1). Because no homozygous individual from S56(t)-sati allele was observed, it was postulated that the allele from O. sativa at S56(t) was sterile (Table 1). The interaction between S56(t)-sati and S56(t)-glum leaded to the complete abortion of the male gametes carrying the allele of S56(t)-sati in the heterozygotes, which resulted in segregation distortion in F2 population. Genetic pattern of S56(t) was consistent with one-locus allelic interaction model (Kitamura 1962) very well.

| Genotype* | Numbers of plants | Pollen fertility (%) | χ2 (1:2:1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DD | 0 | – | 171.85 |

| DG | 201 | 50.27 ± 2.35 | P = 4.3E-38 |

| GG | 227 | 96.48 ± 1.94 |

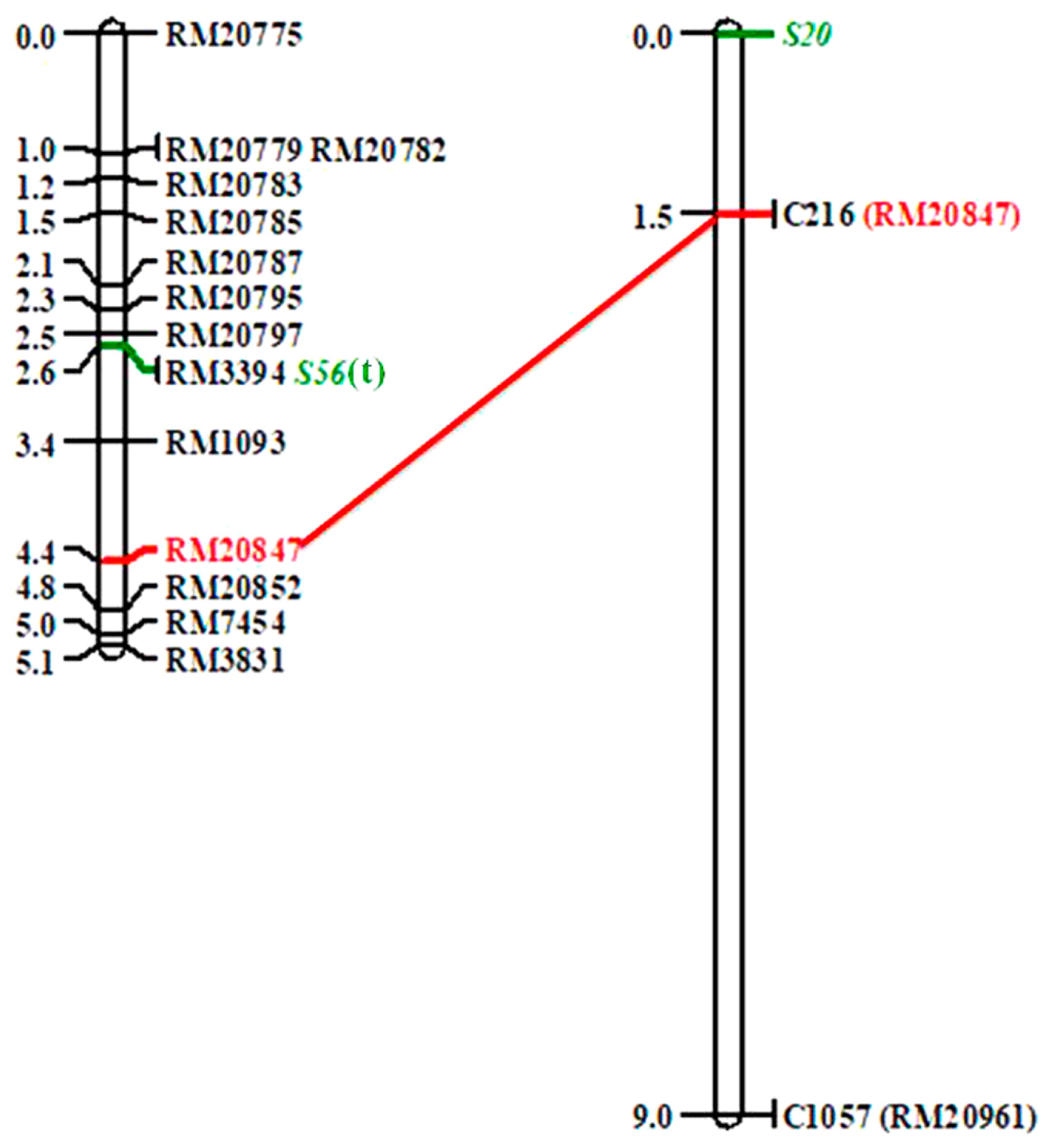

In order to map S56(t) and construct linkage map, 14 polymorphic SSR markers in the introgressed region on chromosome 7 were used to genotype 428 individuals in the F2 population. S56(t) was restricted to a 0.9 cM region flanked by RM20797 and RM1093, at genetic distance of 0.1 and 0.8 cM, respectively, cosegregating with RM3394 (Fig. 2). Based on the GRAMENE public database (http://www.gramene.org), RM20797 and RM1093 were located on bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) accessions AP005187 and AP003746, respectively, of the temperate japonica cultivar Nipponbare, and the physical distance between the two markers was about 469 kb. Mapping region of S56(t) was similar to the region of S20 and qSS-7 identified in a cross between O. sativa and O. glaberrima (Doi et al. 1999, Li et al. 2011).

Linkage mapping of S56(t). The right was cited from Doi et al. (1999). Same marker on the maps was shown, and SSR markers in the bracket were transferred from the RFLP markers.

In this study, we identified an interspecific hybrid sterile locus S56(t) that was involved in male gamete development in hybrids between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula. S56(t) was delimited to physical distance of 469 kb between RM20797 and RM1093 on the short arm of chromosome 7 (Fig. 2). No homozygote from O. sativa at S56(t) locus was observed in the F2 population, suggesting that the pollen grains carrying O. sativa allele aborted completely (Table 1). The number of fertile and semi-sterile individuals in the F2 population fitted the 1:1 ratio well, suggesting that S56(t) was a single Mendelian factor. The genetic behavior of S56(t) fitted in with one-locus allelic interaction model (Kitamura 1962). By now, 5 loci responsible for hybrid sterility between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula have been reported, including S12, S22(t), S23(t), S27(t) and S28(t) (Sano 1994, Sobrizal et al. 2000a, 2000b, 2001, 2002). The chromosomal location of S12 was unknown (Sano 1994). S22(t) and S23(t) were mapped on the short arm of chromosome 2 (Sakata et al. 2014, Sobrizal et al. 2000a) and on the long arm of chromosome 7 (Sobrizal et al. 2000b), respectively. S27(t) was located on the long arm of chromosome 4 (Sobrizal et al. 2001) and S28(t) was located on the short arm of chromosome 8 (Sobrizal et al. 2002). Therefore, S56(t) should be a new gene controlling male gamete development in hybrids between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula.

Hybrid sterility is the most common form of postzygotic isolation and plays an important role in maintaining species identify (Orr and Presgraves 2000, Sano 1986). Understanding the nature of hybrid sterility genes will help to trace evolutionary process of post-zygotic reproductive isolation during AA genome differentiation. S56(t) locus was mapped around S20 and qSS-7 region identified in the cross between O. sativa and O. glaberrima (Doi et al. 1999, Li et al. 2011). S22B in hybrids between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula and S29(t) in the cross between O. sativa and O. glaberrima had good co-linear relationship on chromosome 2 (Hu et al. 2006, Sakata et al. 2014). It is suggested that S56(t) and S22B might originate before the divergence of O. glumaepatula and O. glaberrima. S22A showed coupling-phase linkage with S22B, and independently induced F1 pollen sterility between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula (Sakata et al. 2014); however, S22A was not reported in O. sativa/O. glaberrima hybrid, indicating that divergence of S22A may occur after the speciation of O. glumaepatula and O. glaberrima. The genomic duplication at S27(t) locus also occurred after the divergence of O. glumaepatula and O. glaberrima (Yamagata et al. 2010). In addition, It was observed that S23(t) from O. glumaepatula, and S21 from O. glaberrima and O. rufipogon were located into the similar region on chromosome 7 (Doi et al. 1999, Muyazaki et al. 2007, Sobrizal et al. 2000b). This evidence led us to hypothesize that S21 and S23(t) could originated before the divergence of O. glumaepatula, O. glaberrima and O. rufipogon. Because S56(t)/S20/qSS-7, S22B/S29(t) and S21/S23(t) were identified in the cross between O. sativa and O. glumaepatula or O. glaberrima, the common origin of hybrid sterile genes in O. glumaepatula and O. glaberrima could be suggested, which also agreed with the opinion that origin of O. glumaepatula was from Africa continent and closely related to the O. glaberrima (Doi et al. 2000, Vaughan et al. 2003). Mapping and characterization of more sterile genes, including S56(t), would help us understand the dynamic process of AA genome speciation.

Hybrid sterility is the major obstacle for the utilization of favorable genes in O. glumaepatula. Thus, breaking reproductive isolation is necessary to transfer valuable genes from O. glumaepatula to O. sativa by interspecific hybridization. Previous reports indicated that O. sativa lines carrying S1-g allele from O. glaberrima can be used as the bridge parents to significantly improve the fertility of hybrids between O. glaberrima and O. sativa (Deng et al. 2010), and pyramiding the indica alleles at Sb, Sc, Sd and Se loci and the neutral allele at S5 locus in japonica genetic background through MAS are compatible with indica rice varieties, F1 hybrids show fertile pollen and spikelet fertility (Guo et al. 2016). Therefore, the bridge parents developed by pyramiding S12, S22(t), S23(t), S27(t), S28(t) and S56(t) in Asian cultivated rice genetic background would overcome the interspecific hybrid sterility between those two species.

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31660380, U1502265, 31201196), Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department, China (Grant Nos. 2015HB079).