Article ID: 2024-0013-OA

Article ID: 2024-0013-OA

Evidence-based practice (EBP) plays a crucial role in improving healthcare quality; however, there is still a lack of insight into EBP education for nursing in Japan. We aimed to evaluate the acceptability and preliminary effects of an online EBP education program on undergraduate nursing students in Japan. A pilot, single-armed, pre- and post-intervention design study using mixed methods was conducted with 11 nursing students. Participants completed an 8-h EBP education program over a 2-day period, which provided introductory knowledge and skills based on the five steps of EBP. The total score of the Student-Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire showed a trend toward improvement with a medium effect size (P = 0.06, d =0.51). The following subscales displayed improvement with small to medium effect sizes: “frequency of practice” (P = 0.14, d =0.34), “retrieving/reviewing evidence” (P = 0.04, d = 0.59), and “sharing and applying EBP” (P = 0.13, d = 0.36). The focus group interviews revealed an enhanced understanding of EBP, improved skills for reading articles, and highlighted the importance of interactive teaching and access to on-demand learning materials. Our results suggested that the online EBP education program was acceptable and demonstrated preliminary effects in enhancing the skills of undergraduate nursing students in retrieving and reviewing evidence and results in thematic analysis. Further research such as a controlled trial including a more diverse sample with longer follow-up should be conducted to validate our findings and examine the program’s long-term effects on clinical practice.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a problem-solving approach to delivering healthcare that integrates the best evidence, clinician expertise, and patient preferences.1 Given that EBP is considered imperative for improving the quality and outcomes of healthcare, patient safety, and reducing costs,2,3,4 it plays a vital role in global healthcare systems. Despite the importance of EBP for clinicians and patients, its implementation in nursing is insufficient,5,6 and EBP education for nurses and nursing students is lacking.

Nurses often use experience-based knowledge and rarely adopt evidence from the literature in their practice.5 This is partly caused by barriers to conducting EBP, including a lack of time, poor awareness of current research, inadequate knowledge and skills, and a lack of support from physicians, managers, and other staff.3,5,7,8,9 To overcome these barriers, it is essential to strengthen the understanding that EBP is important to maximize the quality and outcomes of healthcare. Nurses should be educated on skills and knowledge of how to conduct EBP in a way that instills a commitment to EBP.

EBP education and training enable the acquisition of EBP.10 A general consensus in the literature about nursing education is that teaching EBP should occur during undergraduate education.8,11 Several studies have reported the effect of EBP education on nursing students.12,13,14 A systematic review suggested that enhancing health professional students’ attitudes toward EBP could improve their EBP practices through entry-level EBP training.15 In addition, participation in EBP education and experience with research has been shown to be associated with nurses’ competency and belief in EBP.16,17 Moreover, nursing students’ EBP skills are influenced by exposure to education and practice-based experiences.18 Patelarou et al.19 emphasized that teaching EBP skills to nursing students should be a high priority for undergraduate nursing programs to improve their capability. Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that EBP educational interventions for undergraduate nursing students may help nurses overcome the obstacles they would face and facilitate the implementation of EBP after they become nurses.

Despite its recognized importance, EBP education is not yet widely implemented in undergraduate nursing programs. According to several studies, the proportion of nurses who have experienced EBP education remains low.20,21,22,23 This finding can be attributed to the fact that few nursing schools have concrete curricula for EBP education worldwide.24,25 To address this situation, there is a need for investigation of the relationship between the content of EBP education, population, and the level of EBP knowledge and skills.26,27 Therefore, it is necessary to deepen understanding of content and delivery methods that are effective for EBP competency in the population for which it was intended. Furthermore, most EBP education studies use traditional in-person lectures,28 and utilization of an online strategy for EBP education has not yet been examined in Japan, despite the benefits of online learning (e.g., easy access to education) and the importance of adopting information technology in nursing education that was highlighted during the pandemic.29,30,31

Although research on EBP has been growing globally,32 the number of studies conducted in Japan remains limited.33 In particular, there has been a notable lack of studies in Japan that have implemented educational interventions and systematically evaluated their effectiveness. Therefore, we aimed to explore the acceptability and preliminary effects of the EBP education program for Japanese undergraduate students using both quantitative and qualitative approaches. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the acceptability and the preliminary effects of an online EBP education program for Japanese nursing students. We hypothesized that an online EBP education program would improve nursing students’ self-assessed attitude, knowledge, and skills toward EBP. In addition to quantitative evaluation, we employed a qualitative approach to explore and deepen our understanding of the program content that was specifically preferred and affected the outcomes, how the program was accepted, and how it could be improved. This research is expected to lay the groundwork for a full-scale investigation and provide insights into the implementation of EBP education for undergraduate nursing students in Japan.

This pilot study employed a convergent parallel mixed methods design,34,35 incorporating a single-arm, pre- and post-intervention survey to obtain quantitative data, whereas focus group interviews using thematic analysis were used to obtain qualitative data. Both types of data were collected and analyzed concurrently, and the results were integrated to assess the acceptability and preliminary effects of the EBP educational intervention.

ParticipantsWe recruited participants from a university in Japan from November to December 2020 using convenience sampling. The sample size of this study was not calculated because this study was a pilot study. Recruitment was conducted under behavioral restrictions and refrainment because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) third- or fourth-year undergraduate nursing students; (2) able to participate in the program; and (3) consented to participate in the study. Japanese undergraduate nursing students generally participate in a clinical practicum in their second through fourth years and work on their thesis in their senior year. We aimed to recruit nursing students who had experienced a clinical practicum and were (or would be) working on a thesis. We expected that this period would be suitable for carrying out the intervention while the students were learning about research and undergoing their clinical practicum.

InterventionThe intervention was the EBP education program, which allowed undergraduate nursing students to acquire introductory knowledge and skills based on the five steps of EBP. These are described as the basis for both clinical practice and teaching EBP in the Sicily statement,36 and practicing the critique process through published research.37 The five steps of EBP are: (1) asking questions, (2) finding the best evidence, (3) evaluating the evidence, (4) applying information, and (5) evaluating outcomes.38

The objective of the education program was to acquire introductory knowledge of EBP and understand the critique process. The program was developed based on several theories. We employed the backward design framework proposed by Wiggins and McTighe,39 which enables students to gain knowledge and apply it immediately to foster acquisition. We established learning objectives for critical appraisal rooted in the core competencies of EBP. Subsequently, we divided the necessary knowledge and skills into eight learning objectives, structuring the program into eight modules. The sequence of these modules was carefully considered to ensure the progressive application of knowledge acquired in earlier modules. To foster experiential learning based on the cycle of experiential learning theory, each module incorporated a brief lecture followed by a collaborative discussion with a small group. The program was designed so that learners could acquire knowledge through these lectures and immediately apply it to conduct practical, critical appraisals within the discussions. Supplementary Table 1 shows the schedule and brief content of the education program.

The program duration was 8 h over 2 days and comprised eight sections; no reading or assignments were required. The lectures were delivered by a nursing instructor who had substantial experience in EBP education (H.F.). To ensure that the program was delivered as intended, a developer of the education program (A.T.) was present during all sessions to monitor and confirm that the lectures were delivered as designed.

For the lectures, paper documents and a research article were used to practice the critique process. A textbook on EBP was also provided for self-study, but it was not a requirement. At the end of each lecture, time was set aside for small group discussions along with quizzes. The students were separated into groups of three to five participants for group activities. A detailed description of the intervention is provided using the Guideline for Reporting Evidence-based practice Educational interventions and Teaching (GREET) checklist40 in Supplementary Table 2.

Data collectionWe collected quantitative data using an online survey (pre- and post-intervention). The pre-intervention survey was answered after obtaining consent and before starting the intervention, and the post-intervention survey was sent immediately after completion of the EBP education program.

We also gathered qualitative data by holding focus group interviews after completion of the EBP education program. We used focus group interviews to deepen our understanding of the possible preliminary effects of the intervention, verify the acceptability, and obtain ideas to further improve the program. Focus group interviews are broadly used as a qualitative research method to gather in-depth data on topics from a particular population. This approach leverages the dynamic interactions among participants within a semi-structured interview format to generate rich insights41,42 while taking advantage of naturally occurring peer groups to mitigate power imbalances between researchers and participants.43

Participants were notified about the focus group interviews at the beginning of the EBP educational program. We emphasized that participation was completely voluntary and that the participants’ decisions would not affect their class evaluation. One of the researchers guided all focus group interviews according to a semi-structured guide. The focus group interviews were conducted and facilitated by a student (S.S.) at the university where the study was conducted to promote an environment where students could share their thoughts and opinions freely and to provide a psychologically safe environment. S.S. was trained under supervision from H.F., a faculty member at the university with extensive experience in facilitating focus group interviews. H.F. was not responsible for teaching any courses enrolled in by the participants, nor was the faculty involved in their academic evaluation during the study period or in subsequent years.

Each focus group interview was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The focus group lasted until the participants expressed no more new ideas. The main topics of the interviews were how and what were the “changes in knowledge of and attitude toward EBP through the program” and “changes in understanding the meaning of the technical terms used in EBP through the program.”

Measures Demographic dataThe recorded characteristics of the participants included sex and school year, as well as their knowledge of the meaning of EBP (including evidence-based nursing or evidence-based medicine).

Acceptability of EBP education programAcceptability has been defined as the participants’ perception of appropriateness and convenience for the application based on experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention.44,45 At the post-intervention survey, the acceptability of the EBP educational program was evaluated based on two items—the “ease of understanding the program” and “the interest level of the program”—with answers rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

Preliminary effect of participants’ skills and motivation toward EBPTo evaluate the preliminary effects of the EBP education program, we assessed the improvement in nursing students’ competency in EBP. We utilized the Student-Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire (S-EBPQ),46 a self-report measure that tracks the frequency of use, skills, knowledge, and attitudes toward EBP among nursing students. The scale consists of 21 questions divided into four subscales: “frequency of practice” (6 items), “attitude” (3 items), “retrieving/reviewing evidence” (7 items), and “sharing and applying EBP” (5 items). Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale. A summed score was calculated for each subscale, with a higher score indicating greater use, attitudes, knowledge, and skills related to EBP. In addition to the S-EBPQ, the online survey enabled us to identify participants’ level of interest in learning about EBP and the extent to which they were willing to implement EBP in a clinical setting, with answers rated on a 5-point Likert scale. We translated the original English version of the S-EBPQ into Japanese, referring to the validated Japanese version of the EBPQ.47

Data analysisWe summarized the demographic data using descriptive statistics. We conducted paired t-tests to compare the differences in the total and subscale scores of the S-EBPQ between pre- and post-intervention assessments, after confirming the normality of the difference scores using the Shapiro–Wilk test. We calculated the effect size of the total score of S-EBPQ and its subscales using Cohen’s d index. We interpreted Cohen’s d as d ≥ 0.2 = small, d ≥ 0.5 = medium, and d ≥ 0.8 = large.48 We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank sum test to compare the differences in non-parametric data (such as the item “how much participants are interested in learning about EBP”) between the pre- and post-intervention assessments. A priori, we determined that all tests would be one-tailed; P < 0.05 would be required for statistical significance; however, interpretation would not rely entirely on P values but should also include a focus on effect sizes to determine suitable sample sizes for future full-scale studies. We conducted all statistical analyses using SPSS version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and R software system, version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

We analyzed the qualitative data from the focus group interviews using thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a qualitative research method aimed at systematically identifying, analyzing, and interpreting patterns within qualitative data, thereby providing insights into various perspectives of the research topic.49,50 Based on the methodology proposed by Braun and Clarke,49 thematic analysis used the following steps: (1) familiarization, (2)generation of initial codes, (3) searching for categories, (4) review of categories, and (5) defining and naming categories.

One of the authors (S.S.) repeatedly read the verbatim transcripts and listened to the recordings to develop a comprehensive understanding of the data and generate initial codes. During the coding, H.F. supervised the coding strategy and revised the codes. Then S.S., H.F., and A.T. discussed the identification of categories and sub-categories. Definition of the categories and sub-categories was reviewed by all authors until consensus was reached. During the process, re-coding and re-categorization were conducted as refinements.

Ethical considerationsWe conducted this study in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki,51 and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the corresponding author’s affiliate institution (approval #297). All participants were informed that their involvement was completely voluntary, they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time, and data would be treated confidentially. All participants provided informed consent online.

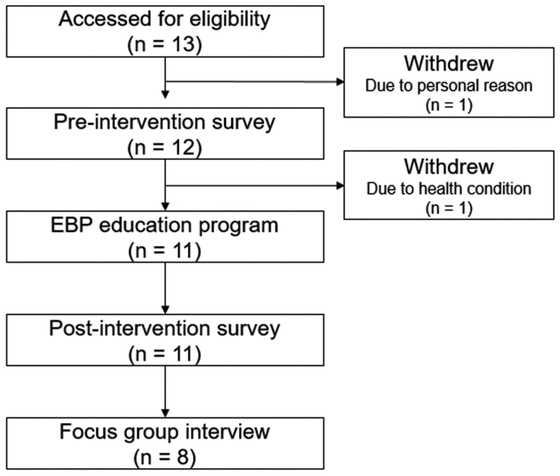

A total of 13 students were eligible and enrolled as participants. We excluded 1 participant before the pre-intervention survey because of a lack of follow-up; another participant withdrew before the intervention because of health conditions. Therefore, 11 students completed the EBP education program and pre- and post-intervention surveys. Eight out of the 11 students took part in the focus group interviews (see Fig. 1). Of the participants, 90.9% were female, and 81.8% were fourth-year students. Three students were unaware of EBP, including the concepts of evidence-based nursing and evidence-based medicine (see Table 1).

Flowchart of participant recruitment.

EBP, evidence-based practice.

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 10 (90.91) | |

| School year | ||

| 3rd year | 2 (18.18) | |

| 4th year | 9 (81.82) | |

| Awareness of EBP | 8 (72.73) | |

EBP, evidence-based practice.

The median [interquartile range: IQR] of the “ease of understanding the program” was 5.0 [4.0–5.0]. Out of 11 participants, seven students scored five, two students scored four, one student scored three, and other student scored two points. The median [IQR] of “the interest level of the program” was also 5.0 (4.0–5.0) with nine participants scoring five, one participant scoring four, and another participant scoring two points.

Changes in S-EBPQ scoresThe total score of the S-EBPQ revealed a difference between the pre-and post-intervention assessments (P = 0.06), and the effect size was medium at 0.51. For the subscales, “retrieving/reviewing evidence” displayed a significant difference (P = 0.04), and the effect size was also medium at 0.59. “Frequency of practice” and “sharing and applying EBP” did not demonstrate significant differences and the effect sizes were small at 0.34 and 0.36, respectively. Only the subscale of “attitude” indicated an adverse effect size after the intervention (d = −0.09) (see Table 2). SupplementaryFigures1–5 show the individual change in total score and each subscale score in the S-EBPQ.

| Component | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | P value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 73.5 ± 19.2 | 83.6 ± 14.8 | 0.06 | 0.51 |

| Frequency of practice | 18.5 ± 9.4 | 21.5 ± 7.5 | 0.14 | 0.34 |

| Attitude | 17.1 ± 2.7 | 16.9 ± 2.5 | 0.39 | −0.09 |

| Retrieving/reviewing evidence | 20.4 ± 8.6 | 25.5 ± 8.1 | 0.04 | 0.59 |

| Sharing and applying EBP | 17.5 ± 4.7 | 19.8 ± 3.5 | 0.13 | 0.36 |

Data given as mean ± standard deviation.

S-EBPQ, student evidence-based practice questionnaire; EBP, evidence-based practice.

While “interest in learning about EBP” and “willingness to implement EBP in a clinical environment,” were rated as 4 or above by 81.8% of the participants, neither item showed significant differences between pre- and post-intervention (see Table 3). Individual change in the motivation toward EBP is shown in SupplementaryFigures 6and 7. Although one person decreased the score of “interest in learning about EBP” after the intervention, four out of eleven improved the score. Three participants exhibited a decline in their score for “willingness to implement EBP in a clinical environment,” whereas six out of eleven demonstrated an improvement.

| Motivation | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interest in learning about EBP | 4.0 [4.0–4.0] | 4.0 [4.0–5.0] | 0.16 |

| Willingness to implement EBP in a clinical environment | 4.0 [4.0–5.0] | 5.0 [4.0–5.0] | 0.56 |

Data given as median [interquartile range].

EBP, evidence-based practice.

Eight students participated in the two focus group interviews. Three nursing students participated in the first focus group interview, and five nursing students participated in the second. The first interview lasted 18 min, and the second interview lasted 26 min. From the focus group interviews, we identified the following three categories: (1) “perceived effects of the program,” (2) “effective methods of program delivery,” and (3) “suggestions for program improvement” (see Table 4). The categories consisted of seven subcategories and 29 codes established by two coders, which were discussed until consensus was achieved.

| Category | Subcategory | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived effects of program | Improved understanding of concept of EBP | Improved understanding of concept of EBP |

| Decreased reluctance toward learning EBP | ||

| Confidence in one’s knowledge of EBP | ||

| Understanding the difficulty of critique | ||

| Improved knowledge of technical terms used in EBP | ||

| Understanding difference between similar technical terms used in EBP | ||

| Improved knowledge and skills when reading articles | Decreased reluctance toward reading articles | |

| Understanding the necessity of critique | ||

| Understanding importance of summarizing articles | ||

| Understanding how to read articles | ||

| Increasing one’s familiarity with research terminology | ||

| Effective methods of program delivery | Effectiveness of group work and feedback | Facilitated understanding through group work |

| Clarification of what is understood and not through group work | ||

| Facilitated understanding through questions and feedback | ||

| Clarification of what is understood and not through questions or feedback | ||

| Easily understandable slides | Easily understandable slides | |

| Facilitated understanding through examples given in slides | ||

| Benefits of on-demand learning materials | Easily taking time to understand the content on-demand | |

| Easily rewinding videos of the program on-demand | ||

| Suggestions for program improvement | Suggestions for program content | Lack of explanation of terms used in statistics |

| Lack of clarification of differences between similar terms | ||

| Difficulty understanding terms related to statistical analysis | ||

| Lack of desire to explain content in detail | ||

| Suggestions for program delivery | Difficulty accessing the information desired | |

| Too fast-paced | ||

| Too little time for group work | ||

| Lack of time and opportunities for self-study | ||

| Suggestions for holding the program over a shorter period |

EBP, evidence-based practice.

“Perceived effects of the program” consisted of two subcategories—”improved understanding of the concept of EBP” and “improved knowledge and skills when reading articles”—and 11 codes (see Table 4). “Improved understanding of the concept of EBP” included seven codes, such as “decreasing reluctance toward learning EBP” and “understanding of technical terms used in EBP.”

I think the feeling of reluctance toward EBP, or EBP knowledge, because of its difficulty, has become more relaxed.

In particular, EBP-related terms that participants were able to understand through participating in the program included: PICO, concealment, blinding, odds ratio, intervention study, observational study, bias, meta-analysis, significance, and clinically meaningful differences.

For me, personally, the program made it easier to understand when I heard about people being blinded, like a patient or a researcher, than reading about it in a textbook.

“Improved knowledge and skills when reading articles” contained five codes, including “understanding how to read articles” and “decreased reluctance toward reading articles.” For this subcategory, the participants reported that their understanding of how to read and summarize articles had improved and that they had become more familiar with research terminology.

As someone said, I think the hurdle of reading academic papers has become lower... I didn’t feel like I wanted to read academic papers—I was totally overwhelmed by the information, and I didn’t understand anything before—now, I understand it is essential to grasp the research and its purpose as an initial step.

Effective methods of program deliveryThis category consisted of three subcategories—”the effectiveness of group work and feedback,” “easily understandable slides,” and “the benefits of on-demand learning materials”—and eight codes. “Effectiveness of group work and feedback” included the idea that group work and feedback can deepen students’ understanding.

We all talked about the content (during the group work) and realized that we had been thinking we understood when we were listening, but actually, we were not... The way the instructor talked was easy to understand, but when we were asked if we understood every little detail, we realized that we hadn’t understood.

“Easily understandable slides” highlighted the participants’ positive perceptions of the understandability of the slides used in the program.

Overall, but especially on the first day, there was a lot of change in my understanding. I think that the first day was really just the basics, but even though it was the basics, it was explained in an easy-to-understand way with many illustrations and diagrams.

“Benefits of on-demand learning materials” refers to the participants’ recognition of the benefit of having access to the program recordings on-demand.

Because the on-demand lectures were videos, we could pause them and listen to parts we didn’t understand again, so I think there was a different kind of merit to it compared to online lessons, which progress according to the schedule.

Suggestions for program improvement“Suggestions for program improvement” consisted of two subcategories—”suggestions for program content” and “suggestions for program delivery”—and nine codes. For “suggestions for program content,” participants expressed difficulty understanding the difference between similar terms (such as “concealment” and “blinding”). Furthermore, some terms were not explained sufficiently (such as “case-control studies, “ “confidence intervals, “ and “P values”).

I think there may be some confusion because of my prior knowledge and the way various people explain things. Still, I think it would have been better if they had explained the terminology in a little more detail, like what it explains, rather than just saying the important numbers.

“Suggestions for program delivery” included feedback that described difficulty accessing information, fast-paced delivery, insufficient time for group work, the need for self-directed learning time, and a preference for intensive programs that last for shorter periods.

The program was easy to understand, but because they were explaining so many technical terms and concepts that were mostly new to me in a limited amount of time... there was so much content for which my understanding was a little behind where I should have been.

The aim of the present study was to examine the acceptability and preliminary effect of an online EBP education program for undergraduate nursing students. We hypothesized that an online EBP education program would improve nursing students’ self-assessed attitude, knowledge, and skills toward EBP. The results showed that the content of the lectures affected the students’ EBP attitude, knowledge, and skills and revealed how and what content was effectively accepted and what content had space for improvement to teach EBP. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the preliminary effects of an online EBP education program for Japanese nursing students using mixed methods. Therefore, our study has several implications for undergraduate nursing education.

First, according to the benchmark of Cohen’s d,48 the effect sizes of the intervention were medium for the overall score and the score of the “retrieving/reviewing evidence” subscale in S-EBPQ, and small for “frequency of practice” and “sharing and applying EBP” subscales, suggesting a practically meaningful improvement. In line with these findings, related categories such as “decreased reluctance toward reading articles” and “understanding how to read articles” were also extracted from the focus group interviews. These qualitative results reinforce that participants perceived the greatest impact in the area of reviewing evidence. Given that the education program was designed to provide a fundamental knowledge of EBP, with a particular emphasis on how to critique research articles, these findings are consistent with the intended objectives of the program.

“Retrieving/reviewing evidence” was the only the subscale that showed statistically significant improvement; however, it is important to note that the sample size was relatively small. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution, and future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to more robustly evaluate the program’s effectiveness. Nonetheless, the results suggest that the program may have a meaningful impact on nursing students’ ability to read and interpret research articles, because the overall score and three subscales in S-EBPQ showed small to medium effect. The objectives of the focus group interviews were to deepen the understanding and interpretation of which aspects of the program were effective and well-accepted, and to identify areas for improvement. According to the results, the practical application of EBP (such as critically appraising research articles) affected students’ EBP skills. The nursing student participants also emphasized the importance of interactive, engaging instructional techniques such as group discussions and the need for more hands-on practice with EBP. This feedback indicated that the backward design framework used to design the program positively influenced students’ learning experiences. The backward design provides evidence of understanding,39 possibly reinforcing their self-assessment of the skills of EBP. This finding supports the suggestions of a previous randomized controlled trial that participants preferred interactive teaching methods to boost their motivation to apply their newly learned skills in the clinical context.52 In addition, thematic analysis showed that nursing students were confused about EBP terms. This outcome is similar to an integrative review of nurses’ readiness for EBP.53 Therefore, educators should focus on helping students understand the meanings of and differences between terms. Suggestions obtained from the analysis to improve the program included the need for time to engage in self-directed learning, more time for group work, easy access to the map or index of the terms used in EBP, and availability of the on-demand lectures. Our results indicate that the participants preferred a blended learning approach to learn about EBP. More research is needed to determine whether (and to what extent) these suggestions are effective.

After the intervention, the mean score of the “attitude” subscale fell by 0.2 points. This result is not surprising because previous studies employing EBP education as an intervention have reported improvements in EBP-related outcomes, such as knowledge and skills among nurses and undergraduate nursing students. However, these interventions did not consistently lead to improvements in attitudes toward EBP.13,54,55 There are three potential factors that may have collectively influenced the results. First, the participants had a high mean baseline score on the “attitude” subscale, which may have created a ceiling effect, making it difficult to detect any significant improvement. Second, the education program may have increased students’ awareness of the challenges involved in implementing EBP—challenges they may not have recognized at the time of the pre-intervention assessment. In the thematic analysis, we identified codes such as “difficulty understanding terms related to statistical analysis,” which reflected students’ realization of the complexity of EBP-related knowledge (see Table 4). These emerging negative perceptions during the post-intervention period may have contributed to a decline in “attitude” scores. Third, the educational content itself may not have been sufficiently designed to enhance attitudes toward EBP. The program primarily focused on foundational knowledge and skills, such as the critique process. Although it addressed the importance of EBP, it may not have adequately demonstrated its practical benefits for clinical outcomes. This lack of applied relevance could also have contributed to the decrease in attitude scores. Given that a systematic review indicated that beliefs and attitudes were associated with the utilization of research in the clinical field, further research should consider including interventions enhancing attitudes toward EBP.56

In the aspect of acceptability, most of the nursing students rated the ease of the online EBP education program as 5 on a scale range of 0–5, and we extracted the subcategory “easily understandable slides” in thematic analysis, indicating that this program was well accepted and easy to understand for undergraduate nursing students. We also identified the “benefits of on-demand learning materials” from qualitative analysis. One advantage of providing lectures online is that the lectures could be recorded and offered for self-directed study. A study using the e-learning approach for EBP education documented that students liked self-paced learning because it provided the option to go back and revisit specific content at a later stage.57 Hence, this advantage may have promoted self-directed study and comprehension of the content.

This study has five main limitations. First, we used a single-armed pre- and post-intervention design, which limits the ability to make causal inferences about the program’s effects. Second, we conducted the study at a single institution in Japan, limiting the findings’ generalizability to other settings and populations. Third, this study has the potential for selection bias. We recruited a relatively small sample size of participants from a single institution through convenience sampling. Moreover, given that the median score of both “interest in learning about EBP” and “willingness to implement EBP in a clinical environment” was rated as 4 even before the intervention, the participants may have held pre-existing attitudes toward EBP that differed from those who declined to participate, which could have influenced the results. Future research should conduct a full-scale study with a larger sample of participants from a broader range of settings to improve the generalizability of the findings. Fourth, this study used a self-assessment questionnaire for quantitative evaluation. Hence, there is a risk of bias, such as social desirability bias and the Dunning–Kruger effect, where the latter is a cognitive bias where individuals with low ability overestimate their performance.58,59 These biases potentially compromise the accuracy of the participants’ actual improvements. In the present study, we observed improvement of self-perceived skills and knowledge of EBP in the reaction level of the educational effect based on the Kirkpatrick model.60 Future research should incorporate objective measures to examine the learning and behavior level of the changes in skills, knowledge, and behavior toward EBP to validate the effect of the EBP education program. Fifth, we used the Japanese version of the S-EBPQ without assessing its reliability or validity, although the original English version of the S-EBPQ has been validated. Therefore, it is possible that some nuances of the instrument were lost in translation, leading to inaccuracies in the assessment of participants’ EBP skills.

Based on the results from the survey and the focus group interviews, we found that the online EBP education program was accepted by Japanese undergraduate nursing students and improved their self-assessed skills in retrieving and reviewing evidence. This study offers important insights into the acceptability and preliminary effect of an EBP education program. A full-scale study with a diverse and larger setting is required to examine the efficacy of the developed EBP education program.

We thank Professor Dominic Upton, Dr. Penney Upton, and Laura Scurlock-Evans for their assistance with the S-EBPQ. We also thank all participants for their kind cooperation. This work was supported by Incentives to Study and Conduct Research through the SFC (Shonan Fujisawa Campus) Education Promotion Foundation and supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP24K13610. The development of the EBP education program and use of the S-EBPQ (Japanese version) was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 18K17452.

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.