2019 Volume 60 Issue 3 Pages 479-483

2019 Volume 60 Issue 3 Pages 479-483

Sm2Fe17N3 powders were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy to elucidate the role of surface Fe oxides in the significant deterioration of coercivity observed when Sm2Fe17N3 is sintered at relatively low temperatures. It was demonstrated that the Fe oxides on the powder surface completely disappear after heat treatment at 500°C in Ar. This suggests that the chemical reaction which causes the coercivity deterioration involves consumption of the Fe oxides. A reaction model that postulates a redox reaction between the Fe oxides and Sm2Fe17N3 to produce soft-magnetic α-Fe consistently explains both the coercivity drop and the consumption of the Fe oxides. The conventional model of simple Sm2Fe17N3 decomposition, on the other hand, cannot rationally explain the disappearance of the Fe oxides. It is therefore reasonable to consider the redox reaction to be the primary mechanism of coercivity deterioration, in which the Fe oxides play a role as one of the major reactants.

Development of novel energy and environmental technologies is boosting demand for high efficiency motors and electric generators, for which high-performance permanent magnets are indispensable components.1,2) While Nd2Fe14B has dominated the market of high-performance magnets for the last few decades, it has a major weakness in that its hard-magnetic performance declines significantly at high temperatures because of its relatively low Curie temperature of 312°C.3) Since the temperature inside the motor of an electric vehicle, for example, rises to 180°C, it is hard to ensure sufficient performance of Nd2Fe14B magnets without adding heavy rare-earth elements like Dy and Tb,3) but the price and supply of those elements are unstable, as resources are limited in amount and unevenly distributed in some countries. New materials are therefore eagerly anticipated.

One of the most promising candidates for post-Nd2Fe14B magnet materials is Sm2Fe17N3, which was discovered independently by Asahi Kasei Corporation and by Coey et al. around 1990.4,5) This material has a saturated magnetization of 1.57 T,6) comparable to that of Nd2Fe14B (1.60 T3)), an anisotropy field of 20.7 MA/m,6) which is three times larger than that of Nd2Fe14B, and a Curie temperature as high as 473°C.6) The excellent magnetic properties of Sm2Fe17N3 are seemingly sufficient for the material to surpass Nd2Fe14B in practical performance at high temperatures without addition of heavy rare-earth elements. Nonetheless, Sm2Fe17N3 has never been used practically in major applications of high-performance magnets due to severe deterioration of coercivity when the powder material is sintered.

It is evident from X-ray diffraction experiments of sintered compacts that the coercivity deterioration correlates closely with precipitation of an elemental bcc Fe phase (α-Fe).7,8) This soft-magnetic phase may provide nucleation centers for reverse magnetic domains, resulting in significant reduction of coercivity. The only widely accepted view thus far for the α-Fe precipitation is thermal decomposition of the magnet phase9,10) expressed by formula (1).

| \begin{equation} \text{Sm$_{2}$Fe$_{17}$N$_{3}$} \rightarrow \text{SmN} + \text{$\alpha$-Fe} + \text{N} \end{equation} | (1) |

It is considered that the Sm2Fe17N3 phase is not thermodynamically stable at any temperature, but only exists as a non-equilibrium phase owing to the high activation energy of formula (1) reaction;11) in other words, it exists on the basis of a “kinetic” stability. The “thermal decomposition temperature” around 620°C is therefore by no means a phase transition point defined in a thermodynamic sense, but merely a temperature region in which the reaction rate becomes sufficiently high. In fact, coercivity drops are sometimes observed even at sintering temperatures far below the “thermal decomposition temperature”.12,13) This is explained in this context by variations in the local chemical states that cause local decreases in the activation energy in some cases.

However, we can also consider an entirely different mechanism in which the Sm2Fe17N3 phase reacts with other chemical species. The powder surface is usually covered by a surface oxide layer, which is located in the grain boundary when the powder is sintered. As previously suggested by Takagi et al., precipitation of α-Fe can also be explained consistently by assuming that the iron oxides included in the surface oxide layer react with the underlying Sm2Fe17N3 phase according to formula (2).14)

| \begin{equation} \text{Sm$_{2}$Fe$_{17}$N$_{3}$} + \text{Fe$_{2}$O$_{3}$ (FeO)} \rightarrow \text{Sm$_{2}$O$_{3}$} + \text{$\alpha$-Fe} + \text{N} \end{equation} | (2) |

In the scenario of formula (2), the iron oxides are essential requirements for the precipitation of soft-magnetic iron. If this is true, it should be possible to sinter oxide-free Sm2Fe17N3 powder without coercivity reduction, but this hypothesis has remained to be verified, since most sintering experiments thus far have been performed using powders exposed to the air.

The only exception is a recent study by Soda et al., which demonstrated that the coercivity deterioration on sintering of Sm2Fe17N3 is evidently related to the occurrence of surface oxides on the Sm2Fe17N3 particles.15) The authors successfully prepared Sm2Fe17N3 powders with a very low content of oxygen, typically 0.2 mass%, with an average diameter of 1.5 µm. They also established that no coercivity drop occurs when sintered magnets are fabricated from these low-oxygen powders at sintering temperatures up to 500°C using a system that excludes oxygen throughout the whole process from powder preparation to sintering.

This experimental fact seems to be explained most simply and naturally by the redox mechanism of formula (2), which postulates an explicit role of iron oxides. However, at this point, we cannot completely exclude the decomposition mechanism of formula (1), if we assume that the surface oxides of Sm2Fe17N3 act as catalysts, instead of reactants, in reaction (1). From this perspective, the low-oxygen powders by Soda et al. are regarded as catalyst-free powders, which do not catalyze the reaction to progress, and therefore do not produce α-Fe at low temperatures.

Which is the true mechanism of the coercivity deterioration on sintering at low temperatures? The most crucial difference between the two models is whether or not the iron oxides appear in the chemical reaction formula. In the decomposition scenario, iron oxides do not appear in formula (1), which means that the surface iron oxides should remain intact after the reaction has been completed. In the redox scenario, on the other hand, the iron oxides are reactants, i.e. indispensable components of the reaction in formula (2). That is, the reactants must be consumed as the reaction progresses, and their depletion terminates the reaction. Thus, it should be possible to judge which mechanism is true simply by comparing the amounts of iron oxides before and after heating air-exposed Sm2Fe17N3 powder in an inert atmosphere.

The present study investigated the surface chemical states of Sm2Fe17N3 powder by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to determine the true mechanism of the significant deterioration of coercivity on sintering of Sm2Fe17N3 at relatively low temperatures. By comparing the Fe 2p3/2 spectra of air-exposed powder before and after heating at 500°C in Ar, we demonstrated that the iron oxides on the powder surface completely disappear after heat treatment and only zero-valent Fe is detected. This is a convincing evidence that some sort of reaction involving reduction of the iron oxides takes place on the surface, which strongly supports the redox mechanism of coercivity deterioration.

The method of preparing the magnetic powder was described in detail elsewhere.15) Briefly, commercial coarse Sm2Fe17N3 powder with a mean particle diameter of 25 µm (Sumitomo Metal Mining Co., Ltd.) was repeatedly pulverized into fine powder with a mean diameter of about 1.5 µm with a jet mill (NJ-50, Sunrex-Kogyo Co., Ltd.) mounted in a glove box filled with highly purified N2 gas with an O2 concentration of less than 1 ppm. Fine Sm2Fe17N3 powder with a mostly unoxidized surface was obtained by this process, since the part of the surface that was newly exposed by pulverization accounted for more than 90% of the total. An “oxidized” powder was also prepared by intentionally creating an oxide layer on the low-oxygen powder. This powder was kept in N2 mixed with 1% O2 for more than a day, and then was exposed to the air.

Heat treatment was applied to both the low-oxygen powder and the oxidized powder in purified Ar gas with an O2 concentration of less than 1 ppm, resulting in a thermal history similar to that of sintering. The temperature was raised firstly at a rate of 135°C/min to 270°C, then at 67°C/min to 470°C, at 10°C/min up to 500°C, at which the samples were kept for 2 or 720 min at maximum, and naturally cooled to room temperature. The sample powders were then set on an XPS sample holder in a glove box filled with purified Ar. More specifically, the powders were simply stuffed into pits made on the sample holder, leveled with the flat end of a spatula, and then carried in a transfer vessel without exposure to the air and placed into the XPS instrument.

XPS was performed using a PHI5000 VersaProve II (ULVAC-PHI Inc.) with a monochromatic Al Kα (1486.6 eV) X-ray source. The base pressure of the system was below 1 × 10−7 Pa. The photoelectron spectra of the Fe 2p3/2 were recorded with a pass energy of 23.5 eV and an energy step of 0.1 eV, while wide-range spectra were obtained with a pass energy of 117.4 eV and a step of 1.0 eV. In addition, spectroscopy and etching by Ar ion sputtering for 30 s at 2 keV were performed alternately to collect information on the depth profiles of the composition and chemical states of the powders. Sputtering depth was calculated from the value of Fe2O3 sputtering rate on literature,16) as a rough indication of the real depth: etching for 600 s corresponds to a depth of 43 nm in Fe2O3 equivalent.

The coercivity values of the magnetic powders were determined by measuring magnetization as a function of the external magnetic field using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) function of a PPMS instrument (Quantum Design, Inc.). The sample powders were embedded in resin to make bond magnets, magnetically aligned in a static magnetic field of 2 T, and then measured with the VSM.

Figure 1 shows the wide-range photoelectron spectra of (a) the low-oxygen and (b) the oxidized Sm2Fe17N3 powders prepared by the above-mentioned procedures. The intensity of the O 1s peak around a binding energy of 530 eV increases more than tenfold when the powder is exposed to the air, which demonstrates that the coverage of the surface oxides is suppressed to a single percent order in the low-oxygen powder.

Wide-range photoelectron spectra of Sm2Fe17N3 fine powder prepared by low-oxygen pulverization process, (a) before and (b) after exposure to air.

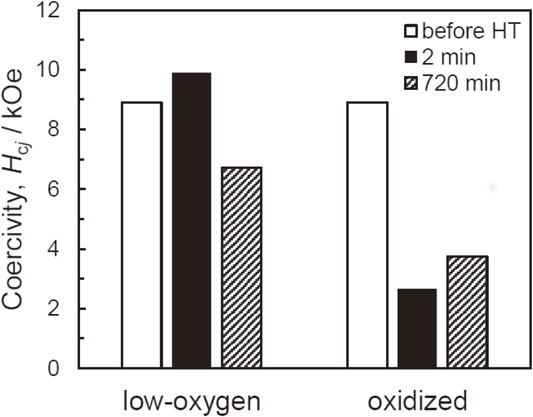

Figure 2 compares the coercivity changes due to heating of the low-oxygen and oxidized powders. After heating at 500°C for 2 min, the coercivity of the low-oxygen powder did not change significantly, but the coercivity of the oxidized powder was reduced to one-third. This result seems consistent with the sintering experiments by Soda et al.15) When the heating time was extended to 720 min, the coercivity of the low-oxygen powder decreased slightly, but still retained a much higher value than that of the oxidized powder. On the other hand, no further decrease in the coercivity of the oxidized powder was observed as a result of the extended heating, indicating that the coercivity drop involving the surface oxides was basically completed and coercivity reached its minimum within 2 min.

Coercivity values of low-oxygen and oxidized Sm2Fe17N3 powders before and after heating at 500°C for 2 min and 720 min in Ar.

Figure 3 shows the Fe 2p3/2 photoelectron spectra of the oxidized powders (a) before and (b) after heat treatment for 2 min. These figures show how the Fe 2p3/2 spectrum changes with Ar etching at a constant rate; that is, the spectrum transitions from the bottom to the top of the figures as etching proceeds. The etched depth at which the topmost spectrum was obtained is roughly estimated as 43 nm in Fe2O3 equivalent. The broad structure located around the binding energy of 710 eV and the sharp peak at 707 eV correspond to various Fe oxides and metallic Fe phases, respectively.17) The spectrum of the unetched surface in Fig. 3(a) exhibits only the structure of oxides. No signal from zero-valent Fe is observed initially, but this signal appears and grows with Ar etching. This indicates the unsurprising fact that the as-prepared air-exposed particles are entirely covered by surface oxides. However, the surface spectrum changes drastically through the heat treatment. As shown in Fig. 3(b), the structures of Fe oxides can no longer be observed in any spectrum of the unetched and etched surface after the 2 min heat treatment, but a single peak of metallic Fe is clearly observed instead. This suggests that Fe oxides have been consumed through some sort of chemical reaction, producing some zero-valent Fe species.

Fe 2p3/2 photoelectron spectra of oxidized Sm2Fe17N3 powder (a) before and (b) after heat treatment. The spectrum transitions from the bottom to the top of the figure as the Ar etching proceeds.

The spectra of the low-oxygen counterparts are shown in Fig. 4. No oxide Fe signals can be seen in any of the spectra, regardless of whether heat treatment is applied or not, and from the beginning to the end of Ar etching. Figure 4(a) and 4(b) appear almost identical, indicating that no significant chemical change takes place in the absence of Fe oxides.

Fe 2p3/2 photoelectron spectra of low-oxygen Sm2Fe17N3 powder (a) before and (b) after heat treatment. The spectrum transitions from the bottom to the top of the figure as Ar etching proceeds.

Focusing on the metallic or zero-valent components of the Fe 2p3/2 level, Fig. 5 compares the peak energy between the non-etched and Ar-etched surfaces after heat treatment. The solid lines in (a) to (d) are the photoelectron spectra for the non-etched, i.e., outermost surfaces, and the dashed lines are those for the surfaces etched for 600 s at 2 keV (= 43 nm in Fe2O3 equivalent), or subsurface states. The peak heights of the non-etched and etched surfaces are normalized by their highest points in order to facilitate comparison of the horizontal positions. Figure 5(a) is for the oxidized powder after the 2 min heat treatment, and the data are the same as the bottommost and the topmost spectrum presented in Fig. 3(b). In this case, the peak position of the non-etched surface shifts to a slightly lower position in binding energy compared to the subsurface state. Figure 5(b) is the low-oxygen counterpart, and the data are extracted from Fig. 4(b). The peak position of the non-etched surface in this case seems not to shift significantly, and the two spectra nearly overlap each other. Figure 5(c) and (d) are similar plots to (a) and (b) except that the heating time is 720 min. Although the time was greatly extended, the results are nearly the same as in the cases of short time heating. The difference of the normalized spectra for the non-etched and etched surfaces in (a), (b), (c), and (d) are plotted in (e), (f), (g), and (h), respectively. As shown in these figures, the slight shift in the Fe 2p3/2 energy of the outermost surface from that of the subsurface is obvious with the oxidized powders but not with the low-oxygen ones, suggesting that some zero-valent Fe phase other than Sm2Fe17N3 may possibly have been formed by heating only on the surface of the oxidized powders.

Comparison of Fe 2p3/2 photoelectron spectra of non-etched (solid line in a–d) and Ar-etched (dashed line in a–d) surface after heat treatment at 500°C. Ar sputtering for etching was performed at an energy of 2 keV for 600 s. The spectra normalized at the maximum intensity are plotted in (a)–(d), and the difference spectra are plotted in (e)–(h). (a) and (e) Oxidized powder heated for 2 min (extracted from Fig. 3(b)). (b) and (f) Low-oxygen powder heated for 2 min (extracted from Fig. 4(b)). (c) and (g) Oxidized powder heated for 720 min. (d) and (h) Low-oxygen powder heated for 720 min.

Although Fig. 3(b) is for the oxidized powder, no Fe oxide signals can be seen, not only in the outermost surface spectrum but also in the spectra for the subsurface region. This means that the Fe oxides which had initially covered the whole surface have truly disappeared, i.e., they have consumed through some chemical reaction. This fact is explained directly by the redox model in formula (2), in which the Fe oxides are reactants and are therefore consumed in exchange for the precipitation of α-Fe. The decomposition model of formula (1), on the other hand, cannot rationally explain the disappearance of the oxides. If that model is true, the Fe oxides should remain intact, which is actually not the case. These points strongly suggest that the redox model is the true mechanism of the coercivity deterioration at low temperatures.

If we attempt to defend the decomposition scenario of formula (1) which itself is unrelated to the reactions of Fe oxides, we have to find some separate side reactions that consistently explain the disappearance of the Fe oxides. However, it is impossible that the oxides are completely decomposed into elemental Fe and O2 at a temperature as low as 500°C, since the thermal decomposition temperatures of Fe oxides far exceed 1000°C.18) This leads to the inescapable conclusion that the Fe oxides are reduced, i.e., the side reaction must be some redox reaction. Considering that Sm2Fe17N3 is the only possible species that can be the reducing agent for the reduction of Fe oxides in the present system, we identify the side reaction as none other than that in formula (2).

In accepting the experimental fact of the disappearance of the Fe oxides, we necessarily reached the conclusion that the reaction in formula (2) occurs. In contrast, there is no evidence that the reaction in formula (1) actually proceeds in parallel with the reaction in formula (2). It is therefore natural to consider the redox scenario as the primary mechanism of the coercivity deterioration.

The redox reaction should be completed in just 2 min of heat treatment, since one of the reactants is totally consumed in that period, as shown in Fig. 3(b). It is therefore expected that further heating, no matter how extended it is, will not cause any additional precipitation of α-Fe. This is supported in terms of magnetic properties by the fact presented in Fig. 2, which shows that just 2 min of heat treatment of the oxidized powder results in a drastic decrease in coercivity, but extension of the heating time to as long as 720 min does not cause any additional coercivity decrease. Thus, it appears that the entire process is completed within the first 2 min of heating, and the depletion of some crucial substance, which in fact is the Fe oxides, prevents any further change.

With the low-oxygen powder, on the other hand, extended heating over 2 min leads to a small decrease in coercivity, as shown in Fig. 2. This is possibly due to surface oxidation by a trace amount of O2 remaining in the Ar, which can be followed by the reaction in formula (2), or proceed through selective oxidation of the less noble element Sm in formula (3), as studied in Nd2Fe14B.19,20)

| \begin{equation} \text{Sm$_{2}$Fe$_{17}$N$_{3}$} + \text{O$_{2}$} \rightarrow \text{Sm$_{2}$O$_{3}$} + \text{$\alpha$-Fe} + \text{N} \end{equation} | (3) |

Another possibility is the decomposition of Sm2Fe17N3 expressed by formula (1), which may progress very slowly on the surface of the low-oxygen powders, but its influence may become visible after long heat treatment. Which of these processes is the dominant mechanism of the slow coercivity decrease observed with the low-oxygen powder, however, is of little significance when discussing sintering, which is completed in only a few minutes.

XPS analyses were applied to air-exposed Sm2Fe17N3 powder before and after heat treatment at 500°C, in order to identify the role of Fe oxides in the significant deterioration of coercivity on sintering of Sm2Fe17N3 at relatively low temperatures. It was shown that the iron oxides initially contained in the surface oxide layer completely disappeared after heat treatment.

The reaction model suggested by Takagi et al., expressed by the redox reaction in formula (2), can consistently explain the disappearance of the Fe oxides as well as the coercivity deterioration. However, the conventional model of simple Sm2Fe17N3 decomposition, expressed by formula (1), cannot by itself rationally explain the disappearance of the Fe oxides. While we can hypothesize a side reaction that separately consumes Fe oxides, this reaction is none other than the redox reaction in formula (2) in the present system. It is therefore reasonable to consider the redox model to be the primary mechanism of the coercivity deterioration, in which the Fe oxides play a role as one of the major reactants.

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP16K06715.