2022 Volume 63 Issue 10 Pages 1310-1316

2022 Volume 63 Issue 10 Pages 1310-1316

Ti–6Al–4V alloy is widely used as a system material in high temperature and high pressure environments in various industrial fields and is difficult to mechanically machine. Thus, high temperature processing methods such as hot forging, rolling, and hot forming are usually applied. Among various methods for deriving optimal molding conditions during high-temperature processing, the dynamic material model suggests energy dissipation efficiency according to the flow stress of the material. However, the energy dissipation efficiency merely numerically represents the change in flow stress, not the metallurgical behavior of the material. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the difference in energy dissipation efficiency in relation to the high-temperature deformation mechanism. In this study, high temperature compression tests were performed on the Ti–6Al–4V alloy. The temperature range was set at 800°C∼1200°C at intervals of 50°C, and the strain rate was set at 1 × 100/sec∼1 × 10−3/sec at intervals of 10−1/sec. Based on the results of the experiments, flow stress and processing maps were derived, and the high temperature plastic deformation behaviors of Ti–6Al–4V alloy were analyzed in correlation with the microstructural changes and mechanical properties according to temperature and strain rate. And the prior beta grain size according to the difference in energy dissipation efficiency was explained for each condition.

As Ti–6Al–4V alloy is an α + β titanium alloy and exhibits low density, high strength, and corrosion resistance, this is an attractive material in various industrial fields where the trend of lightening has recently emerged, and its application ranges have been expanded. In particular, titanium alloys are often used in the aerospace field, which requires low weight and high strength materials, and these alloys are often applied to parts of complex shapes due to the nature of the aerospace industry. For this reason, various processing methods are being applied.1–4) The processing methods of these alloys are mainly based on high temperature processing such as hot forging, rolling, and hot forming, which are largely involved in the change of microstructure of titanium alloys and thus exhibit significant differences in mechanical properties.5,6) Also, in the high temperature processing of titanium alloys, defects or inhomogeneity of materials generated during the process lowers the yield of products and increases the production cost. Therefore, it is important to find the optimal process conditions to utilize titanium, which is relatively expensive in raw material prices.

In the high temperature processing of titanium, there are many process variables to be considered, such as temperature, deformation amount, and strain rate, and in addition, it is necessary to consider the high temperature deformation mechanism of the material, the stable region of plastic process, etc. Y.V.R.K. Prasad7) proposed a dynamic materials model that considers these variables as quantitative values. This could be useful for high temperature processing by making a deformation processing map through quantifying microstructure changes caused by material deformation with energy dissipation efficiency and predicting process conditions in which unstable plastic deformation may occur.8,9) Therefore, it can be useful in deriving optimal process conditions if microstructure changes and high temperature deformation mechanisms can be identified according to the difference in energy dissipation efficiency of the material.

In this study, the high temperature plastic deformation behavior of the material was understood by evaluating the high temperature compression characteristics in accordance with the strain rate and temperature change for the Ti–6Al–4V alloy, and a deformation processing map was produced using the dynamic materials model and Ziegler’s Continuum Criteria.10) Then, the stable and unstable process conditions of the plastic deformation flow were analyzed. In addition, this study aims to understand microstructure changes according to the strain rate, high temperature deformation mechanisms, and mechanical characteristics in connection with the high temperature plastic deformation behavior, and to present optimal high temperature forging and forming conditions.

The Ti–6Al–4V alloy used in this study is a bar type sample with a diameter of 10 mm of commercial grade (Ti–6.06Al–3.86V–0.24Fe–0.013C–0.007N–0.066O–0.004H). In order to evaluate the basic physical properties in a state of the as-received, mechanical properties were measured through Vickers hardness test and tensile test. And initial microstructure was observed by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

The observation of microstructure was performed through a scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JSM-7100F, JEOL) after cutting the specimen and hot mounting in which the specimen was machined by micro-polishing using abrasive papers of #220∼#2000, diamond abrasives of 6 µm, 3 µm, and 1 µm, and colloidal silica. The hardness test was implemented by applying a load of 0.5 kgf for a holding time of 15 seconds using a Vickers hardness tester (Vickers Hardness, HM-200, Mitutoyo) to measure hardness values twice by 10 points in the direction of crossing the specimen, and the mean and standard deviation were calculated. The tensile test was performed at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3/sec using a universal material tester (UTM, BESTUM-10MD, Ssaul Bestech) after machining the tensile specimen with a grip diameter of Φ10, and a measurement section diameter of Φ6 with a gage length of 24 mm in accordance with the standard of ASTM E8M–16a.

A high temperature compression deformation test was performed to understand the physical properties and deformation behavior of the Ti–6Al–4V alloy at high temperature using a high temperature compression testing machine (Gleeble3500, Gleeble System). The high temperature compression specimen was machined to prepare a size of Φ10 × 15 mm parallel to the longitudinal direction of the rod, and a hole of Φ0.5 × 1 mm for mounting a thermocouple was machined in the center of the side of the specimen. The high temperature compression test was conducted according to a total of 7 temperature conditions (800°C, 850°C, 900°C, 950°C, 1000°C, 1050°C, and 1100°C) and 4 strain rate conditions (5 × 100/sec, 1 × 100/sec, 1 × 10−1/sec, and 1 × 10−2/sec) at 50°C intervals in the temperature range of 800°C∼1100°C. Each specimen was tested in an Ar atmosphere chamber with a heating rate of 10°C/sec, a holding time of 1 minute, and a process of air cooling.

For comparing and analyzing the microstructures of the specimens after completing the high temperature compression test, the specimens were processed by micro-polishing in the same manner as the specimen observed earlier after cutting the specimen in the direction of the cross section. Then, the specimens were etched with a Kroll solution (100 ml H2O + 5 ml HNO3 + 3 ml HF) for observing it using an optical microscope, and an electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis was performed on a specific specimen through a scanning electron microscope.

Figure 1 shows the results of the observation of the initial microstructure. The results represented α + β equiaxed structure with a very fine grain size of 4.4 µm on average, and a number of sub-grains were also observed due to the plastic deformation applied to the rod fabrication process. In order to confirm the homogeneity of basic hardness properties and homogeneity of microstructure, Vickers hardness was measured in the radial direction crossing the center of the specimen, and the results are shown in Fig. 2. Considering the hardness measurement error range (±3%) of the test equipment, it was confirmed that most of the hardness values between the measurement points in the Ti–6Al–4V specimen were similar and the specimens were homogeneous as a whole in which the average and standard deviation values were 320 Hv and 11.0 Hv respectively. As a result of the room temperature tensile test of the Ti–6Al–4V alloy, the tensile stress-strain curves were shown in Fig. 3, and the average yield and tensile strength, and elongation were measured to be 876 MPa, 980 MPa, and 16.1% respectively. This is a value representing higher room temperature tensile properties compared to the yield strength of 828 MPa, tensile strength of 895 MPa, and elongation of 10% of typical ASTM B265 Gr.5 Ti–6Al–4V materials.

SEM-EBSD micrograph of as-received Ti–6Al–4V used in the present work (×2000).

Vickers hardness distribution of as-received Ti–6Al–4V alloy.

Tensile stress-strain curves of as-received Ti–6Al–4V alloy.

The true stress-strain curves during the high temperature compression test under various conditions of temperature and strain rate are shown in Fig. 4. In a high strain rate condition, the specimen showed high compressive strength due to the strain rate hardening effect, and as the temperature increased, both the yield strength and compressive strength generally decreased. In addition, in the case of the high temperature compression test conducted at a high strain rate, the fluctuation points of the graph appear early in the compression behavior, which is known to occur when the plastic deformation of the material is unstable or locally concentrated.11) In the case of the compression tests conducted at temperatures above 900°C, the flow stress curves were all very low. The tests at 800°C and 5 × 100/sec showed the highest value of 391 MPa, and the tests at 1100°C and 1 × 10−2/sec showed the lowest high temperature compressive strength of 30 MPa.

True stress-strain curves of Ti–6Al–4V alloy at various temperatures and strain rate; (a) strain rate 5 × 100/sec, (b) strain rate 1 × 100/sec, (c) strain rate 1 × 10−1/sec, and (d) strain rate 1 × 10−2/sec.

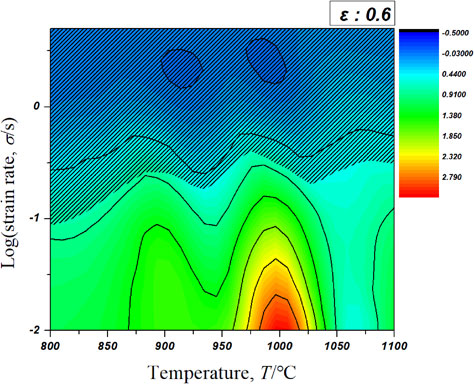

Changes in microstructure during high temperature deformation have a direct effect on the deformation behavior of materials.7,12) Therefore, it is possible to set optimal forming conditions through selecting an effective deformation region and presenting a criterion for controlling the final microstructure. The flow stress in materials at high temperatures increases according to increases in the strain rate under a constant strain, which can be expressed as $\sigma = \text{K}(\dot{\varepsilon })^{m}$, where K is the strength coefficient depending on temperature, strain, etc., and m is the strain rate sensitivity. The value of m serves as a criterion for the stability of plastic flow during its plastic deformation, and is used as an index to derive optimal forming conditions according to temperatures and strain rates, and the range is defined as (0 < m ≤ 1).13)

In addition, the value of m can also be expressed in the form of a slope of the flow stress curve as a function of strain rate at a constant strain (Fig. 5). The energy dissipation characteristics of the material are known through the value m of the strain rate sensitivity. This is because the energy dissipation characteristics are due to the energy consumed by the plastic deformation of the material and the energy consumed by the change in the microstructure when the material is deformed.7) The plastic deformation energy applied to the material consists of two types of energy inside the material, J co-content, which is a power dissipator, and G content, which is changed into heat and dissipated by plastic instability. The total energy applied for the plastic deformation of the material is expressed as eq. (1).14)

| \begin{equation} P = \sigma \dot{\varepsilon} = G + J = \int_{0}^{\dot{\varepsilon}}\sigma d\dot{\varepsilon} + \int_{0}^{\sigma}\dot{\varepsilon}d\sigma \end{equation} | (1) |

Flow stress curves at different temperatures as a function of strain rate (ε = 0.6). Line slopes in these curves means strain rate sensitivity (m).

The energy dissipation efficiency η is a function of deformation temperature and strain rate at a constant strain and can be expressed in the form of a contour on the corresponding plane. The higher this value, the more advantageous the material effectively dissipates and consumes the deformation energy, resulting in active microstructure changes and high ductility,15–18) which can be considered to be a very advantageous condition for mechanical machining. In addition, titanium alloys are phenomenologically easy to spheroidize α-phase under high energy dissipation efficiency.19) In the case of low dissipation efficiency, the plastic instability due to the inhomogeneity of strain acceptance is maximized by the large amount of heat generated, and thus tends to easily generate adiabatic sheer bands and microcracks.16) However, even in regions with high energy dissipation efficiency, there are regions where defects in microstructure occur according to energy consumption patterns, and the plastic stable region and the unstable region overlap. This can be compared and evaluated separately by introducing the plastic instability factor (ζ($\dot{\varepsilon }$)) according to the instability criterion presented by Ziegler10) as Continuum Criteria, and the plastic instability interval is expressed as eq. (2).

| \begin{equation} \xi(\dot{\varepsilon}) = \frac{\partial\ln[(m/m + 1)]}{\partial\,\mathit{ln}\,\dot{\varepsilon}} + m < 0 \end{equation} | (2) |

| \begin{equation} 0 < m \leq 1,\ \frac{\partial m}{\partial (\mathit{log}\,\dot{\varepsilon})} < 0,\ s = \frac{\partial\,\mathit{log}\,\sigma}{\partial (1/T)} \geq 1,\ \frac{\partial s}{\partial (\mathit{log}\,\dot{\varepsilon})} < 0 \end{equation} | (3) |

Deformation processing map shown by temperature-log (strain rate) relation (ε = 0.6); (a) the efficiency of power dissipation (η), (b) Ziegler’s instability criterion (ζ), and (c) complex processing map, slash area means the unstable region.

Microstructures of each temperature-strain rate condition of deformation processing map.

Inverse pole figure map showing prior beta grain restructured by EBSD data at (a) 1000°C, (b) 1100°C.

In the case of a specimen compressed at a temperature of 1000°C or higher, α′ martensite structure was observed. This is transformed into a fully β phase by heating the Ti–6Al–4V alloy with the α + β microstructure above the β transformation temperature (998°C). After that, α′ martensite structure that grew at the interface of β crystal grains was presented during the fast cooling process. The energy dissipation efficiency on the processing map showed the highest level under the temperature and strain rate conditions of 1000°C and 1 × 10−2/sec respectively, and was higher than the specimen at 1100°C under the same strain rate condition. This is different from the general tendency, which shows high energy dissipation efficiency at a high temperature condition, and can be interpreted in connection with the high temperature deformation mechanism of the Ti–6Al–4V alloy. The main high temperature deformation mechanism of the spheroidized Ti–6Al–4V alloy is grain boundary sliding (GBS), and the easiness of GBS appears in the order of the GBS(α/β) ≫ GBS(α/α ≒ β/β) interface in the α + β two-phase titanium alloy.21) Accordingly, it can be seen that less strain occurs due to the grain boundary sliding in the specimen at 1100°C with a complete β/β interface because the experiment was conducted above the β transformation temperature.

Figure 8 shows the reconstruction of the prior β phase based on the EBSD data of the specimens under the conditions of 1000°C and 1 × 10−2/sec with the highest energy dissipation efficiency (η = 3.27) and under the conditions of 1100°C and 1 × 10−2/sec with high deformation temperature but relatively low energy dissipation efficiency (η = 1.23). Here, the average grain sizes of the prior β phase were 285.17 µm at 1000°C condition and 141.38 µm at 1100°C condition, respectively, showing a large difference. The smaller prior β grain size observed in the specimen with a higher temperature condition can be interpreted as the occurrence of dynamic recrystallization under these conditions resulting in grain refinement. The GOS (grain orientation spread) map represented in Fig. 9 shows this result as intuitive visual data from the EBSD test results. In the GOS map, the region with an angle of less than 2° of the grain interface is determined to be dark areas, the region with an angle of more than 2° of the grain interface is determined to be bright areas, and the region with an angle of less than 2° may be considered as a region of occurring recrystallization.22) It can be seen that the dynamic recrystallization occurred more actively in the specimen at 1100°C. Finally, in the results of the high temperature compression experiment of the Ti–6Al–4V alloy with ultrafine grains, it is considered that the conditions of 1000°C and 1 × 10−2/sec, capable of utilizing the high energy dissipation efficiency, is suitable for the optimal process condition for the high temperature forging forming.

GOS (grain orientation spread) map at (a) 1000°C and (b) 1100°C.

The high temperature compression deformation behaviors were analyzed for the equiaxed Ti–6Al–4V alloy with the ultrafine crystal grain of 4.4 µm in connection with microstructural changes, and the following conclusions were obtained.

This work was supported by the Korean government MOTIE (the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy), the Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) (No. 10053101) and the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) (No. P0002019).